The Invention of Martial Arts

Popular Culture between Asia and America

Paul Bowman

3

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bowman, Paul, 1971– author.

Title: The invention of martial arts / popular culture between Asia and America / Paul Bowman.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020016651 (print) | LCCN 2020016652 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197540336 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197540343 (paperback) | ISBN 9780197540367 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Martial arts—Anthropological aspects. | Martial arts—History.

Classification: LCC GV1101 .B68 2021 (print) | LCC GV1101 (ebook) | DDC 796.8—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020016651

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020016652

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Paperback printed by Marquis, Canada Hardback printed by Bridgeport National Bindery, Inc., United States of America

1. Conceptual Foundations—The Invention of Martial Arts: Popular Culture between Asia and America

2. Modernity, Media, and Martial Arts: From Beginning at the Origin to the Origin of the Beginning

3. Martial Arts into Media Culture

4. Everybody Was Kung Fu Citing: Inventing Popular Martial

5. From Linear

Inventing

Acknowledgements

The idea behind this book occurred to me in 2013, and I have been working towards realizing it ever since. However, other things needed to be in place first. This took the form of my 2015 monograph, Martial Arts Studies: Disrupting Disciplinary Boundaries, the establishment of The Martial Arts Studies Research Network, with its annual conferences, and the creation of the academic journal, Martial Arts Studies.

This project really began to find its feet in late 2016, when I secured a research assistant to help me uncover and analyse stories about martial arts in the British press. From that point onwards, over a period of three years, three different research assistants (funded by Cardiff University’s CUROP Programme) assisted me invaluably with different aspects of the project. In 2017, Paul Hilleard worked with me to research British newspaper stories on martial arts and martial artists; in 2018, Jia Kuek helped me to research the British martial arts cultural industry; and in 2019, Kirsten Mackay helped me to carry out broad-based research across a wide range of media, including film and television archives. At the very end of the project, my most eagleeyed PhD student, Evelina Kazakevičiūté, compiled the index. I thank all of these excellent students for their contributions, and the School of Journalism, Media and Culture at Cardiff University, for its consistent support.

I first presented the outline argument and preliminary findings at research seminars in Cardiff University during 2017–2018; one in the School of Journalism, Media and Culture, in December 2017, and another in the Critical and Cultural Theory Seminar Series in the School of English, Communication and Philosophy, in March 2018. I also gave seminars on the research to the Cardiff hub of the Martial Arts Studies Research Network at that time. Colleagues, including George Jennings, Terry Morrell, and Qays Stetkevych, provided invaluable feedback.

The first full draft of the manuscript was written between 2018 and 2019, while I was a beneficiary of Cardiff University’s Distinguished Research Leave Fellowship Scheme. During this time, I was also invited to present drafts of the arguments and research findings in the research seminars of the Institut de la Communication et des Médias, Sorbonne Nouvelle Paris 3, in October 2018, at the kind invitation of Professor Éric Maigret; and in the Department of Media, Culture and Heritage at Newcastle University, at the kind invitation

Acknowledgements

of Dr Darren Kelsey. The work presented on these occasions went on to mature into the cores of Chapters 1, 2, and 3.

Critical ethnomusicologist Colin P. McGuire gave invaluable feedback on an early draft of Chapter 4, ‘Everybody Was Kung Fu Citing: Inventing Popular Martial Arts Aesthetics’. Further valuable input was given by Kyle Barrowman, Spencer Bennington, Daniel Jaquet, Benjamin N. Judkins, Glen Mimura, and other colleagues, when I presented its argument at a research seminar on 22 May 2019 at the University of California Irvine, at the kind invitation of Professors Glen Mimura and James Steintrager. I also presented the core argument and research findings of Chapter 5, ‘From Linear History to Discursive Constellation’, at the fifth annual Martial Arts Studies Conference, held at Chapman University, Orange, California, on 23 May 2019. For hosting this important conference and offering me such a valuable opportunity to present to an audience of respected peers, I thank Professor Andrea Molle of the School of Political Science at Chapman University.

Research for Chapters 6, 7, and 8 took place in 2018, and I was able to present aspects of it, organized around my analysis of the eroticized violence of certain adverts, at the conference, ‘The Pleasures of Violence’, held at Oxford Brookes University, on 7–8 March 2019. For this opportunity, I thank the organizer, Dr Lindsay Steenberg.

Chapter 9, ‘The Invention of Tradition in Martial Arts’, emerged in response to three different calls: first, from Dr Xiujie Ma from the College of Chinese Wushu, Shanghai University of Sport, who spent twelve months under my supervision as a visiting researcher in Cardiff between 2018 and 2019, and who constantly urged me to write articles for a Chinese audience. An initial, shorter version of the core argument of this chapter was written for him, to be translated for publication in China. At the same time, David Lewin and Karsten Kenklies invited me to write on the theme of ‘East Asian Pedagogies: Education as Transformation across Cultures and Borders’. The chapter I wrote for their forthcoming collection also fed strongly into this chapter. Similarly, at that time, a short entry I wrote for a companion to sport in Asia for Zhuxiang Lu and Fan Hong also fed into the work on this chapter.

Finally, Chapter 10, ‘Inventing Martial Subjects: Toxic Masculinity, MMA, and Media Representation’, was written in response to an invitation from Professor Kay Schiller to contribute to the workshop ‘Masculinities and Martial Sports: East, West and Global South’, hosted in the Institute of Advanced Study at the University of Durham, 6–7 December 2018. I thank Professor Schiller for this opportunity. Key evidence that underpins the basis of this chapter’s argument about the media invention of mixed martial arts

(MMA) was provided by my former Ph.D. student, Dr Kyle Barrowman. I thank Kyle for generously sharing with me his encyclopaedic knowledge of MMA and Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) history. The paper he gave at the 2020 Martial Arts Studies Conference, ‘Inventing MMA: On the Political and Cultural Formation of a Concept’, has enormously enriched my own arguments in this chapter.

During 2019, the manuscript for this book received no less than six helpful peer reviews: four anonymous reviews were undertaken by Oxford University Press, and two within the School of Journalism, Media and Culture at Cardiff University. I thank the Oxford University Press reviewers—and Norm Hirschy for supporting this project—as well as my two highly esteemed colleagues, Professor Simon Cottle and Professor Karin Wahl-Jorgensen. All reviewers provided helpful feedback, criticism, and suggestions for improvement. Only one of the anonymous reviewers was overly critical of my approach and my argument (proposing that my argument was ‘obvious’ and that my writing was too dense).

I thank this most critical reviewer in particular, for giving me a clear sense of the ways in which—and the reasons why—this book could be misunderstood and misread. In response to that review, I redoubled my efforts to make the language as accessible as possible while yet still able to express the subtlety and complexity of my argument about the historical emergence—or, as I prefer, the invention of martial arts in international media and culture. Needless to say, all mistakes are entirely my own responsibility. I cordially invite scholars to work with, work over, develop, dispute, reconfigure, and enrich the historical, conceptual, and analytical work I have begun in the following pages.

As ever, I thank my wife, Alice, for her patience in the face of my obsessions. Over time, I have actually come to appreciate the value of a strict ‘no talking about martial arts’ rule that she has long tried to impose. This rule aims to protect not only those around me, but also to protect me from myself. Alice has always enriched me and broadened my horizons, and without her (and her strict ‘do not talk about fight club’ rules), I could well have become a ‘one dimensional man’.

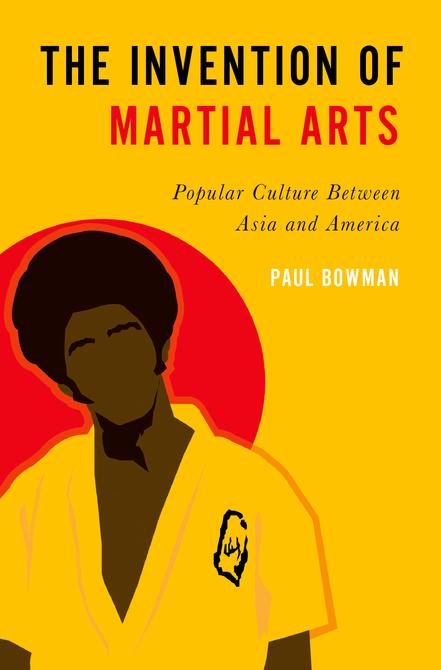

Finally, a word about the cover image. The artist, Jon Daniel, always had an interest in the significance of non-white action heroes for black and ethnic minority children and teens around the world, but especially in the overwhelmingly white context of Great Britain. Jon’s world-famous collection of black popular cultural memorabilia from the 1960s and ’70s, and his series of light-hearted yet serious works, ‘Afro Supa Heroes’, illustrate this passion, and its significance.

x Acknowledgements

When I met Jon, we would always discuss these matters, and we hatched plans to work together in different ways. I began work on a project to produce a series of short documentary films about the status of martial arts in British culture and society. We planned one episode that would feature Jon and other important thinkers and cultural figures in a film that would be entitled ‘Black, British, and Bruce Lee’. To me, this was to be the backbone of the project, and would be the flagship film of the series.

But Jon was taken from us, far too early, in 2017. We never had a chance to work together, and I found that I could not return to that particular project in any way, shape, or form without him. But his artwork, and his important collections live on.

When working with me to create a cover image for this particular book, my colleague, Dr Sara Sylvester, helped me realize that an ideal image for the cover of this book already existed, in the form of Jon’s artwork, titled ‘Williams’. In the influential 1973 classic, Enter the Dragon, Williams is a supporting character to the dazzling Bruce Lee. But he speaks volumes about the international and multi-ethnic appeal of East Asian martial arts in the early 1970s. Indeed, as a figure, Williams is both secondary and yet strangely central. As such, ‘Williams’ amounts to an ideal image for the cover of this present study. I sincerely thank his widow, Jane, for her kind permission to reuse this striking image on the cover of the book. I dedicate it to the memory of Jon Daniel. Whatever else happens with the book in the future, one thing is certain. Thanks to Jon’s artwork, I certainly need not worry about how it looks: in the words of Williams in Enter the Dragon, it will always be ‘too busy looking good’.

Introduction

What Kind of Book Is This and Who Is It For?

This book is based on research into and arguments about a hitherto neglected relationship between martial arts, media, and popular culture. It seeks to contribute specifically to media and cultural studies and to the emergent academic field of martial arts studies. Martial arts studies is an interdisciplinary research area that analyses myriad aspects of martial arts, including practices, histories, traditions, institutions, and textual representations (Bowman 2014a; 2015; Bowman and Judkins 2015). The book is primarily concerned with media representations of martial arts—particularly with the kinds and contexts of representation that have so far been neglected by scholars. For instance, much has been written about martial arts in media such as mainstream film, but considerably less has been written about martial arts in such equally popular and prevalent forms as pop songs, music videos, children’s television and advertisements. These often ignored yet important realms of media culture take up much of the focus of the book. My claim is that no matter how trivial such representations may appear, they are significant and possibly consequential in different ways and thus deserve serious attention for a range of reasons.

The field of martial arts studies uses forms of analysis derived and developed from many academic fields, and involves diverse theories, methodologies, and analytical techniques. This is necessary not only because martial arts studies is an emergent and ‘pre-paradigmatic’ area that is in a sense ‘still finding its feet’ (Nicholls 2010; Bowman 2015) but also because martial arts must be approached as complex practices that exist within the realms of media representation, cultural discourse, art, social institutions, law, commerce, education, and even government policy as much as they exist within specific human minds and bodies, clubs, schools, associations, and lineage traditions (Kennedy 2010; Trausch 2018b). Martial arts are heterogeneous, diverse, multiple, and scattered. They appear in bits and pieces, in proxies, in connotations, associations, condensations, metaphors and metonymies, in different forms, all over media, culture, and society.

This book explores issues drawn from media texts available in the British context and explores them in terms of questions and concerns derived from debates in media and cultural studies, ethnicity and gender studies, martial arts studies, ideology studies, postcolonial studies, and popular culture. In doing so, it incorporates different theories, arguments, and conceptualizations of cultural and social practices, and indeed of culture and society themselves. Some of these may be unfamiliar to non-academic readers or those working in areas of academia that do not incorporate cultural theory. However, when introducing and using theoretical terms, concepts, and arguments, the text has been made as clear as possible, with explanations of what specific technical terms mean, and setting out the most relevant points and contours of the theory or argument in question.

Why Theory?

At first glance, martial arts may seem simple. However, any discussion of them will involve an implicit or explicit theory about them. Indeed, theory is unavoidable in any discussion of culture or society, or any of their features. We can see this in the fact that there are always disputes about what culture and society themselves ‘are’, and hence what the things within them are— what they mean, and what they do. In both academic and wider public discourse, all of this is a matter of dispute. There are many different theories and arguments about what things are and do. Different features and phenomena ‘within’ culture or society can be explained in more than one way, or taken as evidence for very different things. For instance, martial arts practices, when evaluated in terms of one theory, might be read as expressing some fundamental facet of human nature. In terms of another theory, they might be read as media-fuelled escapism (Brown 1997). They may be read as individualistic practices or, conversely, as deeply communal (Partikova 2019); some may regard them as standardizing, or forms of consumerism, while others may see them as stimulating uniqueness and creativity (O’Shea 2018a). Some perspectives can frame martial arts as practices that normalize identities and behaviours (García 2018), while others can perceive ways that martial arts enable multiple kinds of gender, class, ethnic, and other kinds of identity invention, transgression, transformation, and diversification (Brown 1997; Maor 2019); and much more besides.

In this work, I use different theories in much the same way that scientists might use different lenses on a microscope, or different scanning devices, to establish more about the properties of entities and organisms, from

micro-organisms on a slide to symptoms within an entire (social) body. Put differently, just as different kinds of medical scans can draw different dimensions of the human organism into visibility, thereby enabling clinicians to see different things, so different cultural theories provide different ways of looking and different ways of seeing to the cultural analyst (Berger 1972; White 1997; Bowman 2007a; Nicholls 2010).

In the study of culture, different theories offer variations and varieties of perspective. Looking at things from the perspective of one paradigm or orientation, followed by another, and then another is stimulating and illuminating in many ways. The shifts in perspective caused by this can produce more wellrounded or enriched understandings of phenomena, and can also instil a prudent awareness of the limits of our own understanding (De Man 1983; 1986). However, by the same token, such shifts can also produce contradictory, conflicting, incompatible pictures of ‘the same thing’.

Some may regard this situation as potentially paralysing. However, it is actually enabling in many ways. For, both of these consequences of theory (a diversity of interpretations and their potential incompatibility) can enable a more ethical and responsible way of relating to knowledge: we are forced to acknowledge that we only know things in certain ways, ways that are enabled by limited and demarcated viewpoints (Derrida 1992). Consequently, we must remain aware that there is always likely to be more that we are not yet aware of, and that the incompleteness of our knowledge should be borne in mind. Certainly, no single theoretical paradigm or perspective is complete. Applying the framework or analysis provided in one paradigm can produce insightful results about certain aspects or dimensions of martial arts, culture, or society; while, at the same time, that same paradigm will remain unable to ‘see’, ‘deal with’, or ‘say’ anything about other aspects, realms, or registers of that same thing.

In one regard, theory is highly enabling and productive. But, in another, it is as much a source of problems as of solutions, especially in social and cultural studies. Nonetheless, the point to be emphasized is that while some regard theory as an unnecessary ‘digression’, it is more accurately to be understood as a necessary evil (Bowman 2007a). We can never really be free from theory when discussing the human social and cultural world. This is because there is no consensus on how this or these realms ‘work’. The questions, ‘What is culture?’ or ‘What is society?’ and ‘How do or does it or they work?’ have not been answered univocally or in any decisive or satisfactory way (Bowman 2012). There are many competing theories and arguments. Different academic theories—just like different opinions in everyday life—are either based on, reflect, or even actively produce different conceptualizations of culture, society,

and ‘the way the human world works’. So, we can never be free from theory. This means that the meanings and consequences of social and cultural phenomena and facts—such as martial arts—are always open to interpretation. Consequently, rather than trying to reject theory, this work embraces it. Different theories, arguments, and approaches ask us to think about things in different ways, to identify different kinds of details and take them seriously, as possible sources of evidence for interpretations, and to evaluate different kinds of evidence in different ways. In this regard, different theories and styles of approach can be rewarding. But the language of theory can also be offputting to some readers. When faced with cultural theory, for instance, those who have not been academically trained to relatively high levels may feel that they are entering into a world of ‘jargon’.

Jargon versus Technical Language

‘Jargon’ is a pejorative term, and one that is often incorrectly applied. To take any communication to a higher level, as fast as possible, all practices need technical languages. If I were in urgent need of medical treatment, I would not complain if those who were treating me used technical shorthand, abbreviations, and professionally agreed terms. To use an analogy that will bring this back to martial arts: if I go to a new gym or martial arts class, it may take some time to be taught and to master any technique, from a jab to a thruster to an arm-bar, or indeed any exercise or technique. But once I have absorbed something of what goes into the movement or technique, I can happily use the technical term (whether the name of the technique or of the mode of its deployment) to discuss it and take my understanding or my performance forward. A boxing coach does not start every session with a slow run through of how to stand, where to position the hands and how to move in order to throw a jab. It does not take very long at all before a coach can simply say ‘Jab!’ or ‘Arm-bar!’, or indeed ‘Thrusters!’—you name it—and the people they are addressing will understand. The names are technical terms that have a world of technical knowledge condensed into them. Being able to use the name for the thing saves time and enables the forward movement of a discourse.

Academic languages are technical in exactly this sense. This is not to say they cannot be misused or abused, nor be off-putting or inappropriate in certain contexts. Terms that feature in this work, such as text, discourse, hegemony, ideology, identification, semiotics, deconstruction, poststructuralism, among others, have a huge amount of content condensed into them—in much

the same way that jabs, arm-bars, and thrusters have huge amounts contained within them. You can get the gist of the jab in one lesson; you may work on perfecting it for years. In discussing it with others, you may find that there is ever more to say about it. So, in one sense it is simple; in another, it is infinitely and infinitesimally ever-unfolding (Knorr-Cetina 1981; 2003; Spatz 2015). The same is true of academic terms and concepts. You can get the gist very quickly, but it takes work to begin to plumb their depths.

This is the relationship to and use of theory that you will encounter within this book. It uses the language of the field of media, cultural, and martial arts studies; it is in dialogue with these fields and seeks to contribute to them. At the same time, it tries to be as accessible as possible for newer readers, many of whom will find the treatment of martial arts in this way to be unusual. Indeed, some have even found this treatment to be offensive (see Bowman 2016a). However, it is important to point out that, contrary to the alarmed responses of certain critics (especially during the time that academic martial arts studies first started to gain prominence, around 2015), one thing that martial arts studies does not do is ‘separate’ or ‘abstract’ martial arts from ‘reality’, or from their ‘truth’, from ‘real values’, actual ‘practice’, or anything of the sort (Bowman 2016a, 919; 2017a, 61). In fact, if anything, martial arts studies seeks to do the very opposite: by paying serious and detailed attention to social and cultural contexts, histories, relations and forces, representations, political ideologies, economic dimensions, the details of practice, and the many other factors that have a bearing on producing, controlling, or transforming martial arts, from the minutiae of specific practices to the (very) social meanings carried by the term ‘martial arts’ in different contexts; not to mention refining our understanding of why certain martial arts are practiced, with what effects, and so on.

Coverage

This book is the end result of two sustained strands of research and analysis carried out between 2016 and 2019. The bulk of the primary research carried out was on martial arts as they appear and function in mainstream media and popular culture. It is from this wide-ranging research that the case studies discussed in the following pages were selected. During 2017 and 2018 my research was augmented by the invaluable assistance of two research assistants (Paul Hilleard and Jia Kuek), each exploring distinct fields. This was followed up by a period of research leave between 2018 and 2019, during which time I synthesized the research and wrote up this analysis of the findings. The work

of a third research assistant at this time (Kirsten Mackay) helped to enrich and refine its historical and cross-media sweep.

Overall, the book is based on new research into the history and development of representations and treatments of martial arts as they feature within key, but often overlooked, realms of popular culture, with a specific focus on texts as they have circulated within British popular culture. All of this was singled out for research because it has hitherto been significantly underresearched. By comparison with research into martial arts in Asia or America, or the filmic and popular cultural traffic between these geographical and cultural regions, Britain appears as a backwater. Yet, Britain has not only received and consumed Asian and American popular cultural texts about and approaches to martial arts for decades; it has also produced its own martial arts cultural texts. My aim in this research was to uncover and analyse this semiotic environment and discursive context, in order to understand more about the appearance, development, and circulation of ideas about and images of martial arts in media culture.

British popular culture and society has never existed in isolation from the trade route that I am here characterizing as spanning ‘between’ Asia and America; nor can it be divorced from it. The traffic between these two major sources and destinations has had myriad effects on British popular culture. My interest, throughout the research projects underpinning this work, was in exploring what ‘went into’ the production of texts and practices in the British context and exploring the characteristics of British productions, but always within the context of this complex, international textual traffic system. In singling out ‘Asia’ and ‘America’ as key driving forces of martial arts in popular culture, the complex situation of non-Asian and non-American popular cultures is formulated through the at-once clarifying and simplifying image of being ‘between’.

There are problems with this characterization, but there is also ample justification for it. For, when it comes to the production and circulation of martial arts texts, discourses and practices, it is undoubtedly the case that, increasingly throughout the twentieth century, Asia and America have been the two main regional powerhouses of both popular cultural ideas and the most widely known practices of martial arts. This is exemplified both in terms of the growth and spread of martial arts practices in these and other societies and in terms of the scale and impact of the films produced in the film industries of Hong Kong, Japan, and Hollywood—products that constructed, disseminated, fuelled, and fanned the flames of international martial arts booms, crazes, and enduring cultural transformations the world over (Lo 2005; Morris, Li, and Chan 2005; Hiramoto 2014; Marchetti and Kam 2007; Hiramoto 2014; Barrowman 2015).

A visual metaphor for this situation can be found in a scene in the 1982 Hollywood Cold War film, Firefox. In this film, an American military agent (Clint Eastwood) steals the Soviet Union’s new super-jet (the eponymous Firefox)—a jet with amazing qualities, including the ability to remain invisible to radar. As he flies away over a frozen landscape, the pilot inspects the controls in the cockpit and says to himself, ‘Ah, let’s see what this thing can do.’ He then accelerates to astonishing speeds as he tests the manoeuvrability of the jet, flying at a very low altitude. After a few seconds, he notices that flying at such low altitude and at such great speed has caused the jet’s powerful slipstream to throw up a long path of vast clouds of snow and debris. Given that he is attempting to escape Soviet airspace unnoticed and undetected while they are undoubtedly looking for him very intensely, this is a terrible mistake: the snow and debris thrown up like a storm in his slipstream will provide clear evidence to Soviet radar of exactly where Firefox has been, as well as its direction and speed.

This visual image captures something of the situation in Britain and other countries in response to the force of martial arts films, magazines, books, manuals, fashions, and practices flowing out of Asia and America during the second half of the twentieth century. Hugely influential powerhouses of films, television programmes, music videos, magazines, books, fashions, ideas, and embodied practices have flown at low level and great speed across the world, whipping up the terrain and exposing innumerable locales to new ideas, images, ideals, aspirations, fantasies, and lifestyle choices, tearing through and reconfiguring much of the cultural material that was there before—causing turbulence, generating new activity, stimulating excitement and interest, and moving things around significantly (Bowman 2010a). I find this a suggestive way to visualize the cross-cultural traffic of martial arts texts and practices. My aim in this research project was to gain a better understanding of the texts and practices that were produced before, in the tumult caused by, and in the wake of, the most well-known and influential Asian and American martial arts texts and practices that tore through the media and cultural landscape. Simply put, my first questions were: ‘What happened in Britain?’ and ‘What was seen, done, thought, and made here?’

Media History and Cultural Analysis

That particular historical context has not been researched in this way before. However, this book is not simply a work of history. There is certainly both a strong sense of and a respect for chronology and causality within it. But it

does not solely seek to provide a detailed or exhaustive narrative of events. Nor does it give a behind-the-scenes study of production contexts. Rather, it sets out many textual moments and events, zooms in on certain of these, and explores them in terms of questions of how specific stories, issues, representations, and constructions have worked to produce or modify the meanings and values that are given to martial arts in popular culture.

As mentioned, this work is organized by the argument that popular cultural texts, narratives, images, and representations play a crucial, creative role in the invention of wider cultural understandings of martial arts (Iwamura 2005; Goto-Jones 2014; Trausch 2018a). So, the word ‘invention’ in the title refers more to the invention of ideas about martial arts, ways of thinking about them, depicting them, valuing them, and so on, than it does to the work of individuals or groups who have literally invented new martial arts styles or systems. Certainly, some attention is given to such matters; but the main attention is given to the ways that texts play a large part in the creation, circulation, maintenance, and modification of our understandings and values. To use an enduringly popular academic term (one that I discussed in terms of accusations of ‘jargon’, earlier), this work is interested in the creation and development of the discourses of, on, and about martial arts in popular media culture.

In this sense, the work differs both from straightforward historical studies and from the increasingly popular genre of studies that might be called ‘myth busters’ (Henning 1994; 1995; 1999; Wile 1996; Shahar 2008; Lorge 2012; Judkins and Nielson 2015; Moenig 2015). This is not to disparage myth busting. One of the first tasks of the emergent field of martial arts studies involved combining solid historical research (into the origin and development of martial arts) with close attention to the ways that interested parties within and around martial arts have often worked, consciously or unconsciously, to sell images, ideas, and stories about martial arts that are very far from the truth of actual historical reality (Chan 2000). Martial arts stylists tell amazing stories about their art’s historical lineage and the adventures of its founders and central figures. Clubs, associations and entrepreneurs of all kinds capitalize on these myths and legends (Miracle 2015). Regions, cultures, and even nation-states can also ‘cash in’. In fact, there are any number of reasons why all kinds of people can come to believe in and perpetuate mythological fantasies about martial arts—as being ancient, timeless, born on a misty mountaintop, invented by a demigod, unchanging, superlative, philosophical, and so on (Bowman 2017a). Consequently, therefore, there are an equal number of good reasons why scholars might want to engage in myth busting, in order to replace baseless legends with historical facts.

Some really important studies have emerged in recent years that do valuable myth-busting work in all kinds of national, cultural, and ideological contexts (Henning 1994; 1995; 1999; Wile 1996; Shahar 2008; Lorge 2012; Judkins and Nielson 2015; Moenig 2015). Some of the scholars who are engaged in myth busting are effectively at war with myth-promoting powers. Needless to say, I entirely support myth-busting projects. However, this work is not exactly that kind of text. It does something different. As valid and valuable as the orientation is, myth busting is neither the sole nor the ultimate orientation that martial arts studies can or should seek to have. Challenging myths and replacing them with historical facts may answer a need, redress a balance, correct the record, take down some charlatans, and give practitioners a truer sense of their place in larger historical, cultural, political, and ideological processes. But an exclusive focus on myth busting will soon come to be limiting.

This is not to say that it is not important to put the word out there that some of the most well-known ‘ancient’ martial arts emerged in their present forms during the twentieth century. It is valuable to be aware that all styles of karate, aikido, taekwondo, and Brazilian jiujitsu, for instance, are twentieth-century inventions (Funakoshi 1975; Chan 2000; Moenig 2015). Even the avowedly ‘modern’ (late nineteenth- to early twentieth-century) martial art of judo is actually older than many supposedly ancient martial arts. Similarly, what is now known as either kung fu or wushu should properly be understood as a modern construction (Kennedy 2010; Judkins 2014). Perhaps most surprisingly, the ‘ancient’ art of taiji (AKA tai chi, taijiquan, or t’ai chi ch’üan) can actually be understood as a nineteenth-century cultural and ideological response to modernity (Wile 1996). This short list names merely some of the most well-known martial arts.

Throughout this present work, I rely on many valuable studies that have unearthed and examined the historical emergence, technical development, and complex social and cultural situations of different martial arts. However, I also seek to redress another balance and to show the importance and value of other possible focuses, perspectives, and orientations within martial arts studies and media studies. For, overwhelmingly, martial arts studies have tended to focus on the specific practices, histories, and institutions of martial arts themselves. This is hardly surprising. But I have always been suspicious of the tacit assumption that wider cultural understandings of martial arts practices and cultures derive directly or solely from actual practices themselves. Representations of those practices—and, before that, older ideas and fantasies about exotic foreign cultures of origin—have circulated in different media (from literature to journalism to film) and permeated or ‘pre-constituted’ the ways they are most likely to be understood (Krug 2001). So, my question

has been: where do our ideas of martial arts actually come from? There are many issues and factors to consider here, but the answer I put forward in this work is as unequivocal as it is potentially controversial: they come from media representations. It is for this reason that my contention has always been that one of the primary fields of concern in any cultural, social, historical, economic, philosophical, or even psychological study of martial arts should be all manner of media.

Representing Martial Arts in the Media

Those who have read any of my works on martial arts may recall that I have proposed such arguments before (Bowman 2014a; 2014b; 2015). I have made them in my studies of cultural texts that I believed at the time of writing to have been enormously culturally significant and consequential (Bowman 2010a; 2013a; 2017a). Of course, I am certainly not the only person to regard the media representation of martial arts as primary and constitutive of our sense of what specific martial arts ‘are’. But I have in the past received criticism for my attention to mainstream media icons such as Bruce Lee (rather than other, less mainstream figures) and also for my rarely modified operating assumption that the term ‘martial arts’ principally connotes Asian martial arts (Wetzler 2017). Furthermore, there remain significant numbers of scholars who do not respect the status, work, role, and importance of media representations in the constitution, construction, or invention of martial arts. In one respect, this present work seeks to justify, underpin, clarify, and develop all of this more fully.

To be clear, the fundamental argument in play here is based in a rigorously theorized understanding of the notion of representation, as has been carried out in the fields of poststructuralism, critical theory, and cultural studies for well over half a century. The short version of this perspective runs as follows: although we tend to think of representations either as reflecting reality, or as being correct or incorrect, in actual fact, representations construct our sense and understanding of reality (Hall et al 1997). So, although we tend to think of representations as secondary and derivative, hence less important than reality, they are in many respects and contexts our principal access to ‘reality’ (Silverman 1983). In other words, rather than the situation being one of ‘reality versus representation’, it is rather the case that reality is a complex construct made up principally of representations. Moreover, often these representations are rarely of anything more or less real than other representations, in a sea of representations.

This line of thinking has fuelled numerous intellectual traditions, from scepticism to postmodernism. And sometimes it has manifested in people claiming to think either that it is impossible to know or prove anything about reality (or to doubt whether reality exists), or to propose that any reality there ever was has been lost and replaced by a world of unreal representations and simulations. Of course, many of these supposed positions are actually caricatural representations of more subtle and complex arguments. And, when faced with arguments about the primacy of representations, or the ‘loss of the real’, martial artists are ideally placed to argue the contrary and to point out the compelling evidence that there definitely seems to be a reality outside of the world of representation: being kicked and punched, attacked with weapons, twisted, locked, thrown, or choked out, all exist very much for practitioners in the embodied realm of the senses, rather than the realm of ideas, arguments, and signs (Spencer 2011; Downey 2014; Bowman 2018).

But this is not quite the point. In terms of martial arts and the question of the place, role, significance, and effects of representation, the question is not, ‘Do they really exist?’ It is rather, ‘How are martial arts represented?’—what are they depicted and understood as, what codes, conventions, and clichés congregate around them; what common themes recur; who do we see doing martial arts and why; which kinds of martial arts, which styles, and with what wider ideas and values are they associated? To begin to plumb these depths, this work focuses on images of martial arts that circulate in some at once popular and yet critically overlooked media texts. In doing so, it takes a principled stand back from studying martial arts ‘proper’, from looking ‘directly’ at practices, institutions, or their histories. It does so not to deny or hide from the reality of practices, but rather to extend the purview of martial arts studies. Put differently: while more studies of martial arts are being animated and organized by the important insight that martial arts are ‘invented traditions’ (Hobsbawm and Ranger 1983), this work seeks to examine the ways that these invented traditions are also invented (in) traditions of media representation.

1 Conceptual Foundations

The Invention of Martial Arts: Popular Culture between Asia and America

Introduction: ‘Mainly

of East Asian Origin’

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) has an entry for the noun ‘martial art’. It reads:

Chiefly in plural. Any of various disciplines or sports, mainly of East Asian origin, which arose as forms of self-defence or attack, such as judo, karate, kendo, kung fu, and tae kwon do. [ . . . ] more generally: the fighting arts of the warrior. Frequently attributive. Martial arts encompass both armed and unarmed forms of combat, as well as non-combative styles. Though frequently practised for sport or exercise, martial arts traditionally emphasize spiritual training and the unity of body and mind. In the Japanese tradition, the seven martial arts are fencing, spearmanship, archery, horse riding, ju-jitsu, the use of firearms, and military strategy; karate is not considered one of the martial arts.

(Oxford English Dictionary n.d.)

The OED may well be, as it claims, ‘the definitive record of the English language’, but sometimes what it includes—and what it omits—can be regarded as problematic (Williams 1976). Because of this, scholars have sometimes critiqued the OED’s methods, orientations, selections, and approaches. In the case of this definition of ‘martial art[s]’, many martial arts studies researchers could certainly find grounds to contest the key claims that it makes, both in terms of what is included in it and what is excluded from it (Lorge 2012, 9; Judkins 2014, 5). However, my aim here is neither to rely on the OED, nor to critique it. Rather, it is to draw attention to the significance both of something that it includes and something that it omits.

We have already seen what it includes in the definition given above: ‘Any of various disciplines or sports, mainly of East Asian origin, which arose as forms of self-defence or attack, such as judo, karate, kendo, kung fu, and tae kwon do.’ However, it notes that in the formal Japanese tradition, a modern

The Invention of Martial Arts. Paul Bowman, Oxford University Press (2021). © Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197540336.001.0001.

practice like karate is ‘not considered one of the martial arts’. In this, the OED tells us that whereas karate would remain excluded from the category ‘martial art’ in the strict terms of the formal tradition of the literal translation of the Japanese ‘bugei’, it is nonetheless the case that karate is included in the category ‘martial art’ in current English language usage. This is because in English the term ‘martial art’ is a far looser, less literal, and more evocative: it includes sports and self-defence—albeit, ‘mainly’ (the OED asserts) those ‘of East Asian origin’.

Today, the idea that the term ‘martial arts’ is associated with practices that are ‘mainly of East Asian origin’ is contentious. This is so, even though formative works in the field of martial arts studies initially tended, more or less explicitly, to accept the idea that the term ‘martial arts’ in the English language evoked East Asian practices and traditions (Farrer and Whalen-Bridge 2011). However, with the development of such fields and practices as Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA) and the explosion of interest in the indigenous martial arts of all manner of countries, cultures, and geographical regions, many would now contest the claim that the term ‘martial arts’ could, or should, be said to refer to practices that are mainly of East Asian origin (Wetzler 2017).

It is easy to agree with this claim. However, just as the OED does not seek to impute fixed transhistorical values to the terms it nonetheless defines— instead, basing its claims on a sense of their etymological, historical, and cultural development and range of meanings—so it is not my intention to make a transhistorical or logical argument about ‘martial arts’ really referring to a far wider range of practices than those that are ‘mainly of East Asian origin’. Rather, the more important point I want to make is that, despite the potentially transcultural meanings and applicability of the term ‘martial arts’, when it actually exploded into everyday usage in English, it really did refer to practices that were held to be mainly of East Asian origin (Bowman 2010a; Farrer and Whalen-Bridge 2011; Bowman 2013a; 2015; 2017a).

The book you are currently reading details this development. Interestingly, reading between the lines, this development is registered by the list of usage examples that the OED gives for the noun ‘martial art’, which is as follows:

1920 Takenobu’s Japanese-Eng. Dict. 119 Bugei, military arts (accomplishments); feats of arms; martial arts. 1933 Official Guide to Japan (Japanese Govt. Railways) p. clxxxvi Contests [of kendo] take place nowadays at the annual meetings of the Butoku-kai, or Association for Preserving the Martial Arts, in Kyōto. 1955 E. J. Harrison Fighting Spirit Japan (ed. 2) x. 97 Of that branch of Japanese esoterics which belongs to what may generically be styled bujutsu, literally ‘martial arts,’