Acknowledgments

Writing this book has been a great pleasure. Duke University’s generous research funding enabled assistance from keen-eyed students including Melissa Huber, Adrian Linden-High, Elizabeth Needham, Evangeline Marecki, Michael Freeman, and Zihan Chu (my genealogical wizard), as well as supported the book’s illustrations and maps. My department encouraged me to teach seminars that improved my knowledge and understanding specifically and generally, from Mack Zalin’s exploration of Alexander Severus to the stunning team-based Claudium project by Adrian High, Katelin McCullough, Henrietta Miers, Mariangela Morelli, and Crystal Terry. Most recently, a first-year undergraduate seminar in 2019 on “Imperial Women of Rome” reminded me—yet again—of the vital importance of clarity, conviction, and absurdity.

Many others have provided support, suggested different avenues to explore, or reviewed parts of my work. Absolving all for my infelicities and omissions, I thank here Richard Talbert, Eve D’Ambra, Judith Evans Grubbs, Emily Hemelrijk, Tom McGinn, Corey Brennan, Clare Woods, Lucrezia Ungaro, Cynthia Bannon, Jeremy Hartnett, and Kent Rigsby. Stefan Vranka has been a patient and encouraging editor. Roger Ulrich generously provided the beautiful image of Sabina as Ceres from Ostia, and Susan Wood helped locate a photo of Matidia the Younger. I am grateful to countless others for guidance and interest over the years.

I profited enormously from testing select topics in papers whose lively interlocutors encouraged me to refine or broaden my arguments. At the Classical Association of the Midwest and South I presented “Domitia Longina and the Criminality of Imperial Roman Women.” Signe Krag and Sara Ringsborg kindly invited me to a conference in Aarhus, Denmark, on women and children on Palmyrene funerary reliefs (part of the Palmyra Portrait Project), allowing me to focus on the exemplarity of the imperial family. At the Women’s Classical Caucus panel at the Society for Classical Studies I spoke on “Imperial Mothers and Daughters in Second- Century Rome.” Lucrezia Ungaro’s gracious invitation

Acknowledgments x

to speak at “Le donne nell’età dell’equilibrio: first ladies al tempo di Traiano e Adriano,” part of the brilliant exhibition Trajan, Constructing the Empire, Creating Europe, let me explore the topographical imprint of imperial women in Rome. In every case the opportunity to hear colleagues’ related papers was provocative and fruitful.

Individual venues proved equally stimulating. Invitations to Minnesota allowed initial steps on my first chapter, and development of my thinking on imperial women’s sculptural presence in Rome and elsewhere. Greg Bucher invited me to Creighton University to present “Family Matters: Rome’s Imperial Mothers in the Spotlight”; later that year Jeremy Hartnett asked me to Wabash College, where I gave “Alma Mater? Rome and the Emperor’s Mother.” Roberta Stewart welcomed me to Dartmouth, to give “God-Like Power? Imperial Women and Roman Religion” as the Annual Benefactors’ Fund Lecturer. The 2018 Biggs Family Residency in Classics Reunion at Washington University in St. Louis encouraged “Above the Law? Crimes and Punishments of Imperial Women.” At all these fine institutions the questions of perceptive students and faculty sharpened my thinking. At the end, a talk at the Stonington Free Library (Conn.) helped me complete my manuscript. Further, the warm reception in my childhood home encouraged the hope that this project might appeal to many beyond those specializing in Rome’s imperial history.

Tolly

Boatwright Durham, NC

30 June 2020

Abbreviations

For ancient literary works I follow the abbreviations of the most recent Oxford Classical Dictionary other than using “HA” for Historia Augusta rather than “SHA” for Scriptores Historiae Augustae, as the work is sometimes called. Cassius Dio poses special challenges because of the fragmented status of his text, and for convenience I use the book, chapter, and section numbering of the Loeb edition by E. Cary, Dio’s Roman History (London and Cambridge, MA, 1914–27).

AE L’Année Épigraphique, published in Revue Archéologique and separately (1888–).

BMCRE British Museum Catalogue of Coins of the Roman Empire. London 1923–.

CFA Acta of the Arval Brethren; cited CFA and document number as they appear in the authoritative edition of J. Scheid (with P. Tassini and J. Rüpke) (ed.), Commentarii fratrum Arvalium qui supersunt. Les copies épigraphiques des protocoles annuels de la confrérie arvale (21 av.-304 ap. J.-C.), Rome 1998. For convenience the pertinent EDCS referent is also provided.

CIL Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (1863–).

EDCS Epigraphik-Datenbank Clauss-Slaby, http://www.manfredclauss.de/ gb/index.html

FIRA Fontes Iuris Romani Anteiustiniani [FIRA] 3 vol. Florence 1941–1943; reprint 1964–1968.

FOS References to the catalogue of M.-T. Raepsaet- Charlier, Prosopographie des femmes de l’ordre sénatorial (Ier–IIe siècles). Louvain 1987.

ILS Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae, ed. H. Dessau. 1892–1916.

IRT The Inscriptions of Roman Tripolitania, ed. J. M. Reynolds and J. B. Ward-Perkins. Rome 1952.

Abbreviations

LTUR Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae, ed. E. Steinby, 6 vols. Rome 1993–2000. Citations to this are followed by volume number and page, entry, and author of entry, although subsequent citations to the same entry tend to be only to LTUR volume and page.

MW M. McCrum and A. G. Woodhead, Select Documents of the Principates of the Flavian Emperors, A.D. 68–96. Cambridge 1961. OCRE Online Coins of the Roman Empire, http://numismatics.org/ ocre/.

PIR Prosopographia Imperii Romani Saeculi I, II, III, 1st edition by E. Klebs and H. Dessau (1897–1898); 2nd edition by E. Groag, A. Stein, and others (1933–).

RDGA Res Gestae Divi Augusti.

RE Real-Encyclopädie der klassischen Altertumswissenschaft, ed. A. Pauly, G. Wissowa, and W. Kroll (1893–).

RIC Roman Imperial Coinage, ed. H. Mattingly, E. A. Sydenham, et al. (London 1923–1967); revised edition of vol. I only, ed. C. H. V. Sutherland and R. A. G. Carson. London 1984.

RIC II.12 Roman Imperial Coinage. Vol. II—Part 1. Second fully revised edition. From AD 69–96. Vespasian to Domitian. I. A. Carradice and T. V. Buttrey. General editors M. Amandry and A. Burnett. London 2007.

RPC Roman Provincial Coinage, ed. A. M. Burnett, M. Amandry, and P. P. Ripollés Alegre. Paris 1992.

RRC Roman Republican Coinage, 2 vols., ed. M. H. Crawford. London 1974.

RS Roman Statutes, ed. M. H. Crawford. 2 vols. BICS Supplement 64. London 1996.

SCPP Senatus Consultum de Pisone patre, CIL II2/5, 900 = EDCS46400001, cited according to the text as established by Eck, Caballos, and Fernández, 1996.

Smallwood E. M. Smallwood, Documents Illustrating the Principates of Nerva, Trajan, and Hadrian. Cambridge 1966.

VDH The edition of Fronto’s letters as established by M. P. J. Van den Hout, M. Cornelii Frontinis Epistulae. Leipzig 1988.

1

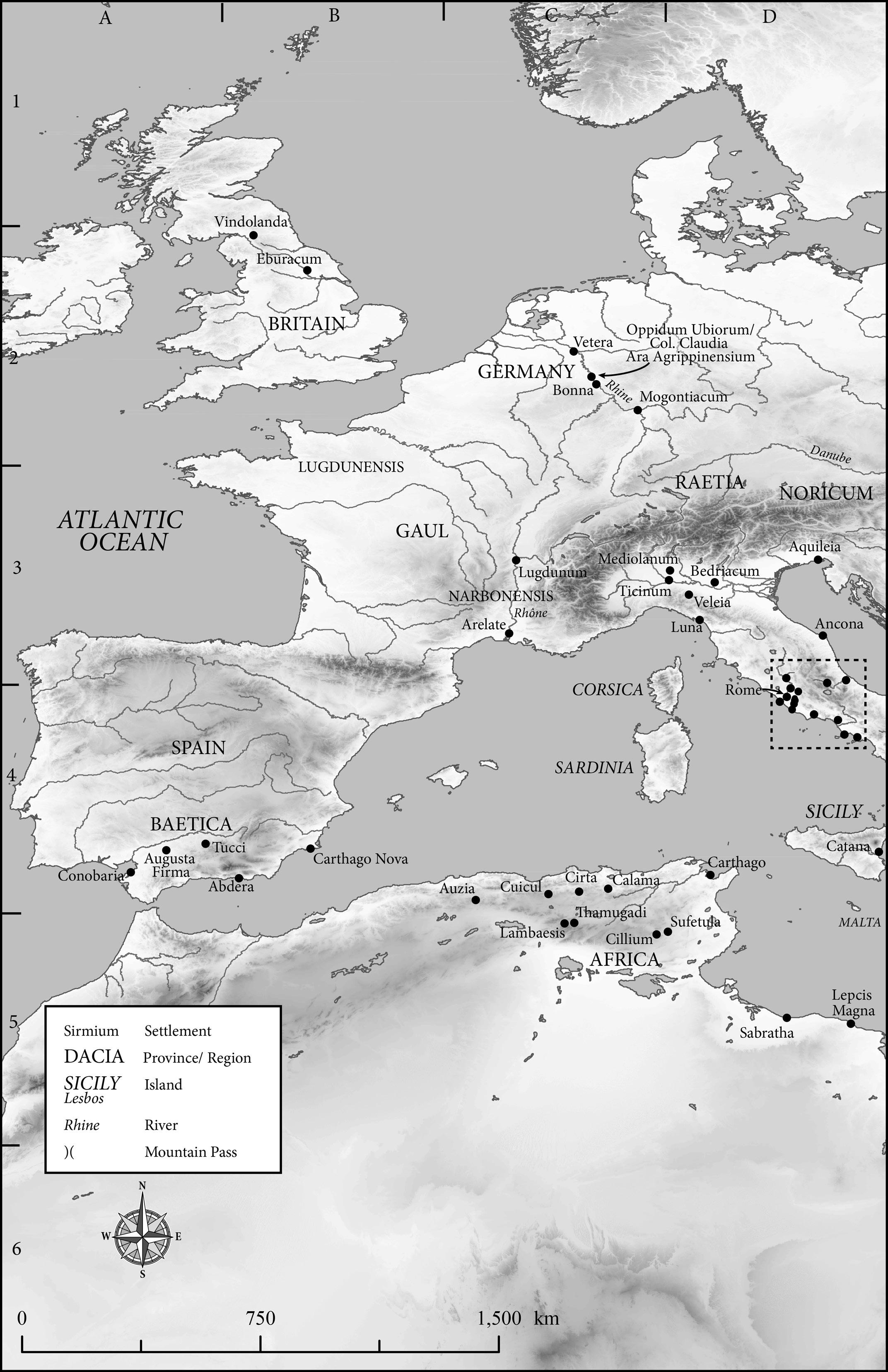

Map

The world of Rome's imperial women. © AWMC.

Introduction: Subjects and Sources

If the Roman princeps was first among equals, what position and visibility did an imperial woman have? Livia, Plotina, and a few other imperial women are celebrated for unwavering support of their emperor and empire;1 Agrippina the Younger and Julia Domna are branded as impudently attempting to assert autonomy and exercise authority; a handful, most notoriously Julia the Elder and Messalina, are luridly depicted as sexually insatiable and manipulative of their exalted positions. Most, however, are more indistinct, as Faustina the Elder, a cipher despite her numerous posthumous portrait coins; Sabina, chameleon-like in her varied portrait statues and lack of presence; or Lucilla and Crispina, mere wraiths overshadowed by Commodus. Considered over time and as a whole, however, these and other women closely connected to the emperors illuminate Roman history and afford us glimpses of fascinating and demanding lives.

From its informal and gradual establishment by Augustus (30s BCE–14 CE) through the end of Severan rule (235 CE), the Roman empire oversaw Rome’s farflung and diverse peoples, religions, languages, and needs. The political system in this period essentially centered on one man, the princeps, whose eminence and authority were based on asserted Republican precedents and vaguely defined powers. Successful, evolving, and often self-contradictory, this principate was an unofficial dynastic system. The second-century Appian saw Augustus’ changes as establishing “a family dynasty to succeed him and to enjoy a power similar to his own” (App. B Civ. 1.5), although Augustus’ apparent claim to have restored the Republic was often repeated.2 Many others similarly recognized the significance of family, and especially of the women related to the Roman princeps by blood or marriage.

1. For the dates and relations of these and other imperial women I discuss, see Appendix 1.

2. RGDA 34.1; Vell. Pat. 2.89.3; ILS 8393 = EDCS-60700127, lines 35–36; see Edmondson 2009, 197–202.

Imperial Women of Rome. Mary T. Boatwright, Oxford University Press. © Oxford University Press 2021. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190455897.003.0001

Subject to Rome’s distinctive gender norms, the wives, mothers, sisters, daughters, and others closely associated with the emperor—individuals embraced in my term “imperial women”—had no legitimate power of their own either individually or collectively. Yet they were key to the new and shifting power dynamics, they were present albeit marginally in Rome’s highest circles, and they partook possibly in momentous decisions but certainly in the best resources of the empire. The investigation of these women clarifies the image and functioning of Rome’s principate as well as its gender roles. At the same time my study elucidates remarkable people overlooked or diminished in ancient and modern accounts of Rome.

I use the expression “imperial women” to designate those who shared marriage or immediate family with the emperor. My term has no equivalent in Latin or Greek. It is not derived from a formal designation as is our “emperor” from the Imperator most Roman emperors bore as part of their name and titles.3 The honorific title Augusta (Sebaste in Greek) was used for a wide assortment of imperial women: wives, mothers, sisters, mothers-in-law, daughters, or other cognate or agnate relatives. By the early third century Ulpian uses “Augusta” apparently to refer to the wife of the emperor, but his are general words (Ulp. 13, ad l. iul. et pap., Dig. 1.3.31; see Ch. 2). The imprecision of “imperial women” as a heuristic term corresponds to the ambiguities of these women’s position and roles, as we see repeatedly in this book. Rome’s empire was never a constitutional monarchy in which succession to the throne was carefully calibrated by descent, legitimacy, or some other stated criterion. Furthermore, women were barred by their gender from holding and exercising command of various sorts, the civil and military positions developed and honed through the long years of Rome’s Republic and whose titles, at least, continued into the principate.

Political and military activities, and other public roles like oratory and jurisprudence, were not only considered inherently male but also those deemed noteworthy by Roman historians and other ancient observers. This reality vastly limits evidence even for women closest to an emperor. The best documented, such as Livia and some others mentioned earlier, have prompted stimulating biographies on which I draw in my research here.4 But mine is not a series of biographies of imperial women. Instead, I aim to explore them as a whole, and to investigate

3. See, e.g., Hurlet 2015.

4. Cited in later chapters, they include K. Welch’s forthcoming monograph on Livia with Oxford University Press.

their activities and visibility over time. These emerge more clearly from a comprehensive view spanning from the establishment of the principate in the 30s BCE by Octavian, with his sister Octavia and his wife Livia, to its violent interruption in 235 CE by the mutinous murder of Severus Alexander and his mother Julia Mamaea.

The lives and experiences of imperial women were shaped by custom and law, the exigencies and failures of the evolving new regime, and the personality, health, and luck of the individuals themselves. The last is the hardest to document and explore even for the best- attested women, although I signal such fascinating particulars in the vignettes that open each chapter. The main aim of my book, however, is to present chronologically the mores, laws, and evolving structures of the most significant functions and venues of Rome’s imperial women. Ch. 1, circling around Livia, probes the powers imperial women were granted or thought to have. In Ch. 2 we turn to Roman law and its impact on imperial women. Ch. 3 inspects, within the wider context of the Roman family, the growing importance of the imperial family as an institution. Ch. 4 explores imperial women’s involvement in religious activities of the principate: here, as throughout this book, I prefer the terms divus and diva to “deified” or “divinized.”5 In Ch. 5 we survey the imprint imperial women made on the capital city of Rome through their movements and presence as well as by monuments associated with them. The briefer Ch. 6 looks at a related type of public modeling, imperial women’s representation through sculpture and relief. Ch. 7 explores the connections of our women to Rome’s military forces and the provinces.

My substantive chapters thus begin and end with activities that Romans considered most inappropriate for women—politics and the military—ones with which imperial women’s visibility was most shocking. Furthermore, as the Severan women were especially associated with Rome’s armed forces, the arc of my book is generally chronological, starting with Livia and ending with the Severans. Within chapters I also tend to proceed chronologically: although Rome’s deeprooted traditionalism means that women are often presented in timeless tropes, one goal of my book is to evaluate change over time. We discuss those changes in Ch. 8, my conclusions.

As we see repeatedly in this book, imperial women’s eminence was contingent on their relationship to the emperor and the imperial house. This

5. For the term divus, see, e.g., Price 1987, 77; Woolf 2008, 242. This chapter is longer than others because a traditional sphere of Roman women’s activity was religious, and because it also reviews using coins as evidence.

was something new, although at first sight reminiscent of the history of some late Republican women (see Ch. 1). The principate was based on family, although—in keeping with the un- and understated power bases of the new regime—it was never an overt monarchy. 6 Around the princeps was an imperial court of family members, freedmen, close advisors, and others who controlled access to him or influenced his reaction to a petition, event, or person. 7 This court system, combined with Augustus’ and later emperors’ emphasis on dynastic succession (see Ch. 3), boosted the wife, mother, daughter(s), sister(s), and other women closest to the emperor. It is reflected variously in our evidence. When Cassius Dio’s Livia urged Augustus to pardon Cornelius Cinna, for example, the prototypical imperial woman asserted that only a wife can be the true confidante of one who rules alone.8 More independent documentary evidence, the Senatus Consultum de Pisone patre of 20 CE, affirms that even Tiberius admitted listening to his mother Julia Augusta (see Ch. 1). Later, Julia Domna is said to have given Caracalla “much excellent advice,” a positive statement qualified immediately by the scandalized note that she “held public receptions for all the most prominent men, just like the emperor” (Cass. Dio 78.18.2– 3).

This latter aspect, the supposed transgressions of women within the imperial house, is reflected in Livia’s reported declaration that it was she who had made Tiberius emperor.9 The last Julio- Claudian, Nero, clearly admitted the situation, at least in Tacitus’ searing histories. In Nero’s short accession speech to the senate paraphrased by Tacitus, the young princeps uses words for “home,” household, and family three times: he promises to hear cases not “within his house” alone, to have nothing for sale or open to influence “in his household,” and to keep separate

6. See, e.g., Hekster 2015 on emperors’ erratic practices regarding dynastic genealogies.

7. See, e.g., Wallace-Hadrill 1996; Winterling 1999; Pani 2003.

8. Cass. Dio 55.16.1–2; see Adler 2011a, 145; Purcell 1986, 93; Ch. 1 below. A different perspective is provided in Vitellius’ speech to the senate urging that marriage between uncle and niece (Claudius and Agrippina) be allowed because an emperor’s wife helps the state by freeing his mind from domestic cares (Tac. Ann 12.5).

9. Cass. Dio 57.12.3. Later, when detailing the worsening relations of Agrippina and Nero and reporting that Agrippina said to her son, “It was I who made you emperor,” Cassius Dio adds “just as if she had the power to take away the sovereignty from him again” and notes she was a private citizen (61.7.3; tr. Loeb). The concept of the imperial woman as “maker of kings” may be reflected in Suetonius’ note, at the beginning of both Galba and Otho, of the patronage of “Livia Augusta” for them when they were private citizens: Suet. Galb. 5.2, Otho 1.1.

his “house” and the state (Tac. Ann. 13.4; see Ch. 3).10 Although the promise was made to distinguish his future actions from those of Claudius, Nero could not keep it (see, e.g., Ch. 2).

The evolving principate meant that no emperor could be isolated from the imperial house and imperial women: even the short-lived principate of Nerva in 96–98, when the emperor was sixty-six to sixty-eight years old, saw a dedication or statue honoring his “imperial” mother (see Ch. 3). The importance of women for the imperial image and for legitimacy is reflected in other ways. Although reportedly estranged from his wife Sabina, Hadrian removed from imperial service the praetorian guard prefect Septicius Clarus, the imperial secretary (and biographer) Suetonius Tranquillus, and others, because they had interacted with Sabina more casually than reverence for the imperial court demanded. If we can believe the fourth-century source for this event, what provoked the emperor was no personal affront to Sabina or Hadrian himself, but rather the slight to dynastic courtly protocol.11 Emphasizing a different aspect of the close-knit dynastic system of the second century, Marcus Aurelius allegedly averred that if he divorced Faustina the Younger, his wife and the daughter of his predecessor Antoninus Pius, he would have to give back her dowry—that is, the empire.12 My book recounts many other acknowledgments of women’s importance to the imperial house and imperial stability.

Yet we also see numerous criticisms of imperial women on various grounds, in fact disproportionately to the general scarcity of evidence for these women. As the above examples suggest, most literary information about imperial women is presented to illustrate imperial men and their decisions, not the women themselves.13 Rome’s patriarchal order was emphasized particularly strongly in the imperial house. A woman’s failings reflected on her husband, father, or another

10. non enim se negotiorum omnium iudicem fore, ut clausis unam intra domum accusatoribus et reis paucorum potentia grassaretur; nihil in penatibus suis venale aut ambitioni pervium; discretam domum et rem publicam. When Nero acted to reduce Agrippina’s power he removed her from his house (domus) and transferred her to the one Antonia had owned (Tac. Ann. 13.18).

11. HA, Hadr. 11.2: familiarius se tunc egerant quam reverentia domus aulicae postulabat. Scholars debate the particulars of this incident, usually assumed as 122 and in Britain: see esp. Birley 1997, 138–41, and 333 n.26; Fündling 2006, 581–88.

12. HA, Marc. 19.8–9. See Wallinger 1990, 47–51. Burrus earlier expressed the idea when trying to restrain Nero from divorcing Octavia, Claudius’ daughter (Cass. Dio 62.13.2).

13. For instance, a passage emphasizing Domitian’s vicious unpredictability notes incidentally that Julia, the daughter of Titus, nominated Lucius Julius Ursus as consul for 84 CE (Cass. Dio 67.4.2). Similarly, the report that Vitellius’ wife Galeria Fundana saved the consul Galerius Trachalus from execution in 68 stresses not her bravery, but rather the savage volatility of the early Vitellian reign when no effective emperor had control (Tac. Hist. 2.60.2).

man responsible for her: for instance, Messalina’s sexual escapades serve to underline Claudius’ lack of control. Further, imperial women’s propinquity to the most powerful man in Rome apparently caused others to view them distrustfully and, as we see in Ch. 1 and elsewhere, unusually targeted some women as peddling influence and imperial favors. Despite such biases and other source problems, discussed further later and in individual chapters, enough evidence remains for Rome’s imperial women to allow us to trace, over time, the actions and roles of various ones in various contexts, and to illuminate a number of different features of the principate. Sir Ronald Syme once wrote, seemingly in remorse for the topic, “Women have their uses for historians” (Syme 1986, 169). My study, in contrast, examines imperial women as worthy subjects in themselves, as well as for the insight their reported activities provide for the history of imperial Rome as a whole.

My chapters open with a vignette about a particular imperial woman or women engaged in some activity or situation relating to that chapter’s larger issues, to remind us that these were real individuals in heady circumstances and under intense scrutiny and pressure. My focus on those at the top of Rome’s center of power, however, means less attention to other aspects of the principate. I cannot address fundamental topics such as the vast numbers of enslaved and freed, even those serving imperial women; imperial relations with provincials and the poor; and administrative and military hierarchies below the very highest level, especially in the provinces. Such topics appear occasionally—for example, Ch. 7 includes a section on the provincial travels of imperial women—but it would be a different, less focused book to have explored them as well as imperial women. Nonetheless, the book as a whole should contribute to our understanding of larger-scale structures and changes in the principate, even while it brings to life some of the intriguing women who witnessed Rome’s history in the making even if they did not personally direct the course of events.

Tacitus and other Roman historians appear frequently in what follows, but I turn also to legal codes, coins, inscriptions, and other sources less familiar to the general reader. The literary accounts are usually inadequate and often tendentious.14 Generally, what interested most ancient historians of the principate were the emperor, the men around him, and political and military affairs, and they were generally indifferent to women and children, especially girls.15 Even

14. A further complication is the restricted access to information Cassius Dio laments for the principate (53.19).

15. The rare reports about a child usually presage the later behavior of a notable man, as when Suetonius details Nero’s childhood and musical training (Nero 6, 20).

some of my most important information is incomplete and incidental, such as the report of Livia’s enrollment “among the mothers of three children” and vote of statues as consolation for the death of her son Drusus in 9 BCE (55.2.5–55.3.1; see Ch. 1). Cassius Dio continues from this note to explain briefly that the “right of three children” could be granted to those “to whom Heaven has not granted that number of children.” Writing in the early third century, he adds that formerly the senate but now the emperor made such grants—thus leaving unclear who made the grant to Livia—and that even gods could receive the privilege so as to inherit. Then he concludes, “So much for this matter,” and turns back to his main theme: Augustus and what the princeps did that year.

Other literary evidence more clearly exhibits loaded rhetoric and terms. For example, Tacitus notes the dedication by Julia Augusta (Livia) and Tiberius of a statue of divus Father Augustus at the Theater of Marcellus in 22 CE, an act also recorded by a public calendar. Tacitus, however, uses the occasion to declare deteriorating relationships between the two and to direct blame to Julia Augusta.16 This second-century historian and others frequently charge Rome’s imperial women with “jealousy” and “envy,” especially regarding other women, as well as with greed and peculation.17 Besides obscuring the indubitable friendships and other ties among Rome’s elite women,18 each such report would repay a close feminist reading. My main focus is historical, however, not historiographical. Throughout the following pages I try to attend to the larger contexts as well as do some justice to the subtleties of the evidence.

To aid readers’ comprehension, I provide numerous illustrations, plans, and a map of the empire. Other than the empire’s capital city, consistently called Rome, I identify ancient sites with their modern toponym at first mention even should that be in a footnote; thereafter I refer to them by their Roman names. The twopage map of the Roman empire in my front matter locates, by ancient topynym, cities and most sites mentioned in my text, allowing the reader to trace imperial women’s travels and locations outside Rome.19 Four in-text tables summarize complicated information. The three appendices cover material useful for every

16. Fast. Praen. ad 23 April = EDCS-38000281; Tac. Ann. 3.64.2; discussed further in Ch. 5.

17. See, e.g., the jealousy and animosity of Livia, Agrippina the Elder toward Munatia Plancina, and Messalina: Tac. Ann. 2.43, 11.1, and 11.3; Cass. Dio 58.22.5; Ch. 2 below.

18. A good instance is Tac. Ann. 13.19: after Nero snubbed Agrippina late in 54 no one visited her other than a few women, “unclear whether from love or hate,” then exemplified by a long discussion about one such visitor, Junia Silana, and her insults from Messalina and Agrippina.

19. My index also references each site by grid square on my map. I follow the same identifying principle about toponyms in Appendix 3, but cannot include all those sites on my map. In a few instances I also use modern terms, such as the Balkans.

chapter. Appendix 1, “Imperial Women and Their Life Events,” notes full names and information for the imperial women discussed in my book;20 Appendix 2 presents four genealogical trees: the Julio- Claudian Family, the Flavian Family, the Second- Century Imperial Family, and the Severan Family. Appendix 3 is a chronological list of consecrated imperial women with the major references for the cult of each, which is complemented by a short, unreferenced list of consecrated imperial men until 235 CE.

I have adopted the following conventions for dates and names. Unless otherwise remarked, all dates are CE, that is “from the Common Era,” and in passages that might otherwise be confusing I note BCE (Before the Common Era) and/ or CE. Other than in Appendix 1 I use the names by which my subjects are generally known, including familiar renditions such as Julia and Gaius (rather than Iulia and Caius). This can pose a challenge: for example Livia, Augustus’ wife and prototypical imperial woman, had the full name “Livia Drusilla,” which officially changed to “Iulia Augusta” (Julia Augusta) after Augustus’ testamentary adoption of her in 14 CE. Unless the discussion might become unclear I use the name chronologically appropriate to the argument at hand, a practice I use when referring to Rome’s first emperor now known as Octavian (Gaius Julius Octavianus) during his rise to power in the 40s and 30s BCE, but as Augustus (Imperator Caesar Augustus) after consolidation of that power in 27 BCE. Otherwise I use the commonly accepted names for emperors—for example, Vespasian, rather than “Imperator Titus Flavius Vespasianus Caesar,” and Severus Alexander, rather than his birth name “Bassianus Alexianus,” or “Imperator Caesar Marcus Aurelius Severus Alexander Augustus, son of Publius,” his name often cited in inscriptions from his reign. I generally use the full name the first time an individual is mentioned in a chapter, but thereafter the person’s more common referent or a shortened form. Ch. 2, for example, begins by discussing the wife of Domitian as “Domitia Longina,” but then usually refers to her as Domitia. Severan women appear as Julia Domna, Julia Maesa, Julia Soaemias, and Julia Mamaea when first introduced in a chapter, but thereafter usually as Domna, Maesa, Soaemias, and Mamaea. Other than in tables where space is at a premium, I use “the Elder” and “the Younger” rather than “I” and “II” (or maior and minor).

When referring to primary sources, I quote Latin and Greek mainly when making an argument about the content, bias, or reliability of a passage. When citing inscriptions I generally provide the original reference in Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL) or the like, supplemented whenever possible with the 20. Since there I also give references to FOS or another prosopographical source, I do not repeat such references when discussing an individual in the narrative.

corresponding entry in the Epigraphik-Datenbank Clauss-Slaby or EDCS. EDCS is electronically searchable, frequently provides links that include photographs, and usually indicates more recent publications of the inscription. Thus, for example, in Ch. 2 I make a point about imperial women’s occasionally ruinous identification with their husbands by citing CIL VIII 22689 = EDCS-24100029. Most references to coins are to the standard and easily available Roman Imperial Coinage or RIC, 21 and I almost exclusively discuss coins struck by the imperial mints predominantly at Rome and for circulation in Rome, Italy, and the West. These I call “centrally struck coins,” “central coins,” and “central coinage” (rather than “imperial coinage” or “official coinage”).22 Finally, whenever possible I provide information about provenance and current location for statues and busts, citing the objects according to their museum inventory numbers. Dimensions are in the metric system.

The evidence and analysis in this book reveal that many elements of imperial women’s lives remained constant over the two and a half centuries I survey, but particular roles and images fluctuated. Throughout, from Octavia through Julia Mamaea, imperial women were supposed to exemplify womanly virtues, especially deference, obedience, and family support.23 As female members of the imperial family, they represented stability and the future. Other than within the family, their most acceptable functions in Rome were religious, a traditional locus of women’s activities, and the growth of imperial cult encompassed imperial women first as priests in Rome and then as objects of cult themselves. This was a development that affected women’s lives throughout the empire, as we see in Ch. 4. Yet imperial women’s most important roles were as acquiescent helpmeets to the emperor. Above all, they were not to act independently or flaunt their resources and proximity to power in any way. This is particularly clear in historians’ denunciations of imperial women who allegedly deviated from the ideal and strove for more than was thought due to their gender and their duty. The following pages show both that roles and ideals did change over time, and that imperial women were individuals who often fit imperfectly the positions they held by marriage or birth. The investigation of these women reclaims their value as individuals even as it illuminates the times and structures in which they lived.

21. Metcalf 2012, 3–11, provides an excellent introduction to numismatics. RIC is the reference used in OCRE or Online Coins of the Roman Empire, http://numismatics.org/ocre/

22. See, e.g., Hekster 2015, 6, 30–32. That the imperial mint for gold and silver was established first at Lugdunum (modern Lyon, France) around 14/12 BCE (Strabo 4.192) is immaterial to my argument.

23. I use the term “exemplarity” in this book to mean deliberate showcasing as a model rather than typicality or worthiness as a model.