Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful to the many people and institutions who have made this book possible. Two wonderful friends and mentors have particularly influenced my development as a historian and this book. Tom Griffiths has been unfailingly generous with his time and wisdom. He has always been a sensitive reader and supportive of my aspirations for this work as well as more broadly as a historian. He is the model of a mentor and historian, and his dedication to the scholarly art that is history is an inspiration. Mark Carey took a punt on a distant Australian for a postdoc on his project on the history of humans and their relationship with ice. He was welcoming as both friend and colleague in Eugene, Oregon, and I was sad to leave after my two years were up. He has also been a model to me as a mentor and historian in his care for my personal well-being and career and in his deep engagement with my work.

Most of the work on this book occurred when I was a PhD student in the School of History, Research School of Social Sciences, at the Australian National University. It is a pleasure to recognize the generous financial support of ANU with a vice chancellor’s scholarship, which included not only a stipend but also a healthy research budget that allowed extended trips to many archives. In our usual habitats of the Coombs Tea Room and the University House gardens and bar, the school staff and my fellow PhD students were wonderful companions on my journey, and I am thankful to them for reading drafts, listening to and discussing ideas in formation, or generally supporting me in becoming a historian. Thanks to them and others at ANU, including Joan Beaumont, Brett Bennett, Alexis Bergantz, Frank Bongiorno, Nicholas Brown, Murray Chisholm, Doug Craig, Robyn Curtis, Hamish Dalley, Karen Downing, Kim Doyle, Arnold Ellem, Diane Erceg, David Fettling, Niki Francis, Barry Higman, Meggie Hutchinson, John Knott, Cameron McLachlan, Tristan Moss, Cameron Muir, Shannyn

Acknowledgments

Palmer, Anne Rees, Libby Robin, Blake Singley, Karen Smith, Carolyn Strange, and Angela Woollacott.

This book underwent much revision and refinement while I was a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Oregon. Here I gratefully note the support of the National Science Foundation under grant number 1253779. In addition to Mark Carey, I found myself in a wonderful community of scholars in the Robert D. Clark Honors College and the wider university. For their engagement with my work, my thanks to Hayley Brazier, M Jackson, Katie Meehan, Olivia Molden, Marsha Weisiger, Tim Williams, members of the Glacier Lab, and the engaged honors students of my Antarctic history seminar. After Eugene, I was very happy to arrive at the University of Melbourne as a McKenzie postdoctoral fellow, where the very final touches to this book happened, and I am thankful to my new colleagues in the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies for welcoming me.

I am thankful to others at various conferences and archives around the world for sharing their knowledge of Antarctica and environmental and international history more generally. A small band of Antarctic historians and other humanities scholars has been a wonderful community to be in, and my thanks especially to Adrian Howkins, Peder Roberts, Lize-Marie van der Watt, Elizabeth Leane, Marcus Haward, and Cornelia Lüdecke. I am grateful to the SCAR History Expert Group and Social Sciences Action Group for a travel grant in 2013. For opportunities to publish elements of my Antarctic research during the work on this book, I am grateful to Klaus Dodds, Alan Hemmings, Peder Roberts, Lize-Marie van der Watt, Adrian Howkins, Wolfram Kaiser, Jan-Henrik Meyer, Marcus Haward, and Tom Griffiths. At Oxford University Press, my thanks to Susan Ferber and Alexandra Dauler as well as the two anonymous reviewers for their crucial input.

My time in archives and libraries has been enhanced by many dedicated and knowledgeable librarians and archivists, and I am grateful to them all. In Australia, to the staff of the National Archives of Australia, especially Christina Beresford and Barrie Paterson of Hobart and Kerry Jeffery of Canberra, as well as to the staff of the National Library of Australia, the Basser Library of the Australian Academy of Science, the Australian Antarctic Division Library, and the Australian National University Library. In New Zealand, to the staff of the National Archives and of the Alexander Turnbull Library and to Neil Robertson of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. In the United Kingdom, to Ellen Bazeley-White and Joanna Rae

of the British Antarctic Survey; Shirley Sawtell and Naomi Boneham of the Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge; Renuke Badhe and Rosemary Nash of the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research Secretariat, Cambridge; and the staff of the Royal Society Library and Archives and the National Archives of the United Kingdom. In the United States, to the staff of the National Archives and Records Administration at College Park, the Library of Congress, the Archives of the National Academies of Science, the Hoover Institution Archives, and Stanford University, as well as to Claire Christian of the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition, Washington, DC.

Many dear friends have also seen this book and me develop over the years and have at various points housed, fed, and endured me. My particular thanks to Madeline Cooper, Danae Paxinos, Lauren Hannan, and Luisa De Liseo. Finally, and most importantly, my deepest thanks are to my family, Fernanda and Peter, Marco and Georgia. While I completed my studies and work in Canberra and Eugene (among other places), they were always there in Melbourne, a wonderful and welcoming home. This work would be impossible without them.

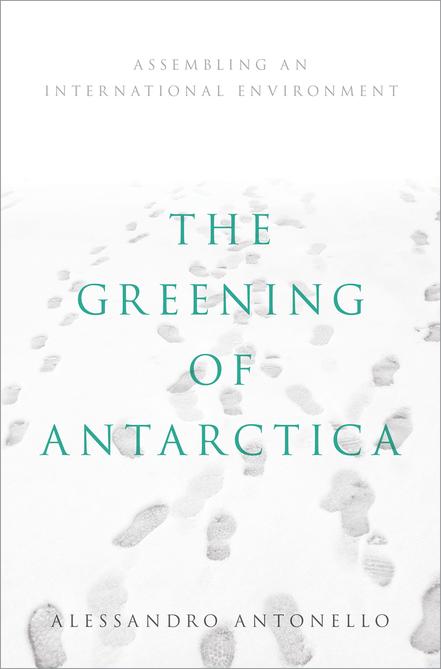

The Greening of Antarctica

Introduction

Order, Power, Authority and the Antarctic Environment

“The d I s TI ngu I shed represen T a TI ve of the United States has told us that we all know what Antarctica is.” These were the arch words of a Soviet diplomat, spoken in the heat of negotiations on the Antarctic Treaty in late October 1959.1 Gathered in a conference room in Washington, DC, in October and November 1959, representatives of twelve nations were negotiating a treaty for the peaceful uses of, and freedom of scientific investigation in, Antarctica. Following the Second World War, international tensions had been developing in the Antarctic, arising from a contest for territory, geopolitical position, resources, and scientific knowledge. The diplomats from these twelve nations agreed that their treaty had to apply to a specific geographical area; “Antarctica” seemed obvious, but the strictures of international law and diplomacy demanded specificity. The pointed observation, even sly criticism, of the Soviet diplomat—“has told us that we all know what Antarctica is”—suggested that the diplomats and scientists of the twelve nations did not, in fact, agree on what Antarctica was. Uncertain knowledge and only incipient environmental sensibilities mapped onto diplomatic disagreement and tension.

The Soviet diplomat—Grigory Ivanovich Tunkin, head of the legal department of the Soviet foreign affairs ministry and one of the leading international lawyers of his day—was not simply dissembling or being contrarian, despite the reality of Cold War competition.2 On that day the conference discussed the “zone of application” of the potential treaty, a question that touched on the sensitive issue of the freedom of the high seas that had been animating international legal and diplomatic

negotiations at the time. Tunkin’s point referred to the complexities— indeed, the unknowns—of geographical, scientific, and environmental imagination about Antarctica in the late 1950s and the ways those imaginings and conceptualizations might be codified into a reliable treaty text. It was an issue that threw into relief each nation’s distinct historical experience of the Antarctic, those who claimed sovereignty over Antarctic territories, and those who denied that sovereignty could exist there. It was an issue that suggested tensions about how to use Antarctica and how to structure peaceful relations around such uses. It was a question of exactly which parts, which elements of the great and complex, though not entirely known, Antarctic region, were really of concern to these nations.

International legal practice relied on land to set borders and boundaries and to structure relations, so Antarctica, with its ice in various forms and its encircling cold ocean, as well as simple lack of knowledge, challenged textually tidy legalities. Tunkin noted that “in the Russian language Antarctica means the whole area around the South Pole,” implying both land and oceans. He added, “The scientists of many countries believe that the boundary of that area is the line of the Antarctic convergence, that is to say, where there is a meeting of the waters of the south regions with those of the temperate regions of the Southern Hemisphere”; this was indeed the geographic area of concern to the newly created Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR).3 Tunkin’s Soviet colleague Alexander Afanasiev, a senior polar bureaucrat, noted a few days after the first intervention on the matter: “Until now, the definite boundary of the real Continent of Antarctic which is under the ice has not yet been determined, and in fact the visible boundaries of the Antarctic Continent are more or less everywhere not determined by the coastline.”4 During the ongoing discussion, the Australian delegate—Australian foreign minister Richard Casey, who had a decades-long connection with and interest in the Antarctic—pursued the matter further, offering the point—“not an entirely fantastic one,” he thought—that “we do not know yet whether the Antarctic is a Continent. It may well in the course of time by investigation turn out to be an archipelago, a series of islands.”5

All these words were spoken in a meeting room in Washington, DC, where the Conference on Antarctica, attended by ninety-nine delegates, was gathered. Perhaps only five of those delegates had actually been to Antarctica.6 Most of the other delegates were acquainted with the region through their official responsibilities as officers in foreign ministries and other bureaucracies, or as diplomats in embassies; they had read reports

about scientific efforts there and had dispatched cables and memorandums around the world discussing the various advantages and disadvantages of particular political schemes and scientific plans. Some were clearly more conversant with matters Antarctic than others. This was a drama not of heroic deeds upon the ice or ocean, but of argument and contestation over the negotiating table.

The Antarctica under negotiation at this conference, therefore, was something both real and imagined. As Richard Casey’s comment about Antarctica being an “archipelago” suggests, some in the room were conscious of the material reality of the Antarctic, a region of ice, ocean, rock, and animals. The International Geophysical Year (IGY) of 1957–1958, which had in part influenced the geopolitical situation, had profoundly altered and increased knowledge of the region. Yet the material and natural Antarctic was only unevenly present in the words and actions of the negotiators. The preponderance of diplomats, politicians, and international lawyers—as opposed to scientists—around the table is suggestive of the most pressing concern: geopolitical order and stability at a time of tensions to prevent disorder and potential conflict. Antarctica was obviously the place they were concerned with, but the Antarctic they had in mind, which was eventually articulated and codified in the Antarctic Treaty, was a relatively sterile and abiotic continent, with loose and oblique talk of resource prospects. Really, it was a stage for their geopolitical relations and contests. As Casey noted in his diary, “The Treaty in the broad was designed to create stability and a sense of permanence in the Antarctic, so that we would all know where we were.”7 Casey’s spatial metaphor here did not refer to the where of the Antarctic region—its wildlife, ice, and seas—but rather to the geopolitical positioning and relationships of the states involved.

Twelve nations did eventually sign the Antarctic Treaty, on December 1, 1959. The treaty was the beginning of what has now become known as the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS), a wide-ranging suite of international law that provides for free scientific research in Antarctica and comprehensive protection of its environment. The twelve original signatories were the only “consultative” members of this regime—that is, members with voting and negotiation rights within the meetings—until 1977, when Poland became the first new consultative party added.8 If, in 1959, there was disagreement over what exactly Antarctica was, in the decades since, ever-increasing knowledge of the Antarctic, a larger place for scientific voices, profound changes in concepts of the global environment, changes in international

political economy, and the continuing reality of national self-interest have meant that the idea of what Antarctica is has changed significantly but has also stabilized in both diplomatic and scientific terms.

Between the signing of the Antarctic Treaty in 1959 and the signing of the landmark Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) in 1980, a group of states and their diplomats and officials, scientists, and scientific institutions transformed the Antarctic from a cold, abiotic, and sterile wilderness, a lifeless and inert stage for geopolitical competition, into a fragile environment and ecosystem demanding international protection and management. Arising out of a contest for power, control, and authority, this transformation occurred in environmental, scientific, geopolitical, and diplomatic registers and was embedded and codified in international treaties. In successive meetings, in diplomatic cables, and in publications and correspondence, these states and scientists assembled the contemporary Antarctic from an array of ideas, natural entities and bodies, laws and relationships, spatial formations, and temporal conceptions, codifying these to stabilize and make orderly not only interstate relations, but also the human relationship with the Antarctic environment.

Two deeply related developments defined Antarctic history in the 1960s and 1970s.9 The first was a conceptual transformation from the idea of a sterile and abiotic continent, shaped by geophysical sciences, to a vision of a living, fragile, and pristine Antarctic region that included the Southern Ocean and was shaped by the biological sciences. The second development was the negotiation of a suite of international treaties and associated agreements for the conservation and protection of the Antarctic environment. Together, these two developments constituted the greening of Antarctica and the assembly of an international environment. The term “international environment” encompasses the links developed among the physical environment, the world of ideas and sensibilities attaching to it, and the legal framework articulated through treaties to govern that environment and the people and states who lived with it.10 Furthermore, the meanings here of the word “environment”—as well as the closely associated and overlapping ideas of conservation, preservation, and protection— must be understood as historically contingent and specific.

The greening of Antarctica was articulated and codified in four major agreements. The first substantial agreement following the Antarctic Treaty was the Agreed Measures for the Conservation of Antarctic Fauna and Flora (AMCAFF) in 1964, negotiations for which began almost immediately after

the signing of the treaty. The next major “environmental” agreement the parties made was the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals (CCAS) in 1972, negotiated after 1964 and partly arising from the limited geographical reach of AMCAFF. The third major environmental agreement and negotiations related to the question of mineral resources and exploitation began in 1969 and culminated in a temporary moratorium agreement in 1977. And the fourth agreement, signed in 1980 following discussions that began mid-decade relating to fisheries and their exploitation, was the legally novel CCAMLR, rooted in the marine ecosystem.11

Each of these agreements held the endings and beginnings of long histories of scientific, environmental, cultural, and political engagement with the Antarctic. These texts had many authors, including the twelve states that negotiated and signed them, many individual diplomats and scientists, and other states and individuals besides the treaty parties, who influenced negotiations from outside the regime. These texts, both explicitly and ambiguously, articulated and codified visions of what Antarctica should be, governed legitimate and illegitimate actions, opened up and foreclosed avenues of development, and were inclusive and exclusive of certain actors. Their geographies manifested those that dominated at the time of signing and also normatively inscribed the region for the future, and they suggested histories and futures. These international legal texts were central to the process of knowing the earth. In a way these processes were, as Erik Mueggler has described in the rather different context of botanical collection in China, “putting earth onto paper.”12 Treaties are richer texts than their legal contexts might initially suggest, especially in Antarctica, where they are invoked almost daily, whether rhetorically or legalistically.

As with so many natural environments, there is a tension regarding Antarctica between the environment of the imagination and texts and the material world that people faced and were forced to engage with. There was not, and is not, a straightforward or self-evident relationship among diplomats, scientists, and environments; the nonhuman world, and human relationships with it—whether exploitative or conceptualized in terms of conservation, preservation, or protection—had to be imagined and constituted in various realms of thought.13 These ideas and bodies of thought were tied, with varying intensities, to the material Antarctic. People’s interactions with a material environment are profoundly shaped by their ideas and preconceptions about it. For Antarctica, in addition, not only are states’ and scientists’ relationships with it mediated by such ideas,

but these ideas have the force (weak or strong as it is) of international law and geopolitical reasoning.

The story of the greening of Antarctica in the 1960s and 1970s reveals substantial issues and a time period that are distinct from other, more dominant perspectives on and approaches to Antarctic history, both in social science and humanities scholarship and in more general histories. The image of diplomats, officials, and scientists imagining Antarctica and assembling an international environmental order differs substantially from the well-known stories of the discoveries and researches of the “heroic era” of the early twentieth century, when the likes of Robert Scott, Ernest Shackleton, Roald Amundsen, and Douglas Mawson were exploring—and Scott and Shackleton dying in—an almost completely unknown region, racing for the South Pole, racing for discovery, recognition, and glory.14 Furthermore, elucidating the competing claims to authority and power in Antarctica during the earliest decades of the treaty shifts attention away from the preoccupations of other scholarship relating to international environmental politics that seeks to evaluate effectiveness, success, or failure in particular regimes, as important as that work is.15

Focusing on the 1960s and 1970s also redraws the periodization of Antarctic history and reframes understanding about the origins of conservation and environmental protection in the region. The rejection of the Convention on the Regulation of Antarctic Mineral Resource Activities (CRAMRA)—negotiated between 1982 and 1988—and the subsequent negotiation and signature of the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (the Madrid Protocol, signed in 1991) are generally portrayed in popular discourse—and to a lesser, though still significant, extent in certain academic literatures—as the turning point of environmental politics and protection in Antarctic history.16 Though undoubtedly the source of the current environmental regime in Antarctica, the Madrid Protocol’s principal concepts and regulations—its specific conceptions of environmental protection, environmental impact, and associated and dependent ecosystems, as well as its rhetoric of environmental stewardship drawing on a closed international system—perpetuated those generated and negotiated in the treaty’s first two decades. Even CRAMRA contained ideas and articles that perpetuated the environmental order established up to the signature of CCAMLR in 1980. The diplomats and scientists who rejected CRAMRA and negotiated the Madrid Protocol were working on a stage that had been set, to a significant degree, in the 1960s and 1970s.17 They obviously could have rejected and reframed the entire

environmental and scientific edifice—a radical and perhaps untenable counterfactual act—yet they perpetuated it. It was between the signing of the Antarctic Treaty in 1959 and CCAMLR in 1980 that Antarctica’s modern international environmental character was substantially developed and entrenched.18

Changing ideas about the Antarctic environment gave the Antarctic Treaty parties new ground—literally and rhetorically, new lands and seas—on which to exercise their powers and attempt to advance their positions. Their geopolitics was not carried out on an unchanging and timeless vision of the Antarctic. The Antarctic environment was reinterpreted, re-envisioned, and invested with new meaning over these two decades, and it was seen and made legible in new ways. By 1980 the Antarctic was a very different assemblage of concepts, ideas, histories, sciences, material things and entities, relationships, spatial formations, and temporal conceptions.19 The various human and nonhuman, material and imagined elements of the Antarctic were enrolled and assembled in specific ways to advance the competing and overlapping political, environmental, scientific, intellectual, cultural, and commercial projects for Antarctica. By 1980 the Antarctic was not simply, as the historian Stephen Pyne put it, “a white spot on the globe” after its exploration, but a complex region of life with an equally complex human regime engaging with and managing it.20 By seeing and recognizing the various elements of the whole Antarctic environment—the terrestrial and marine ecosystems, the geological elements—the Antarctic Treaty parties were creating new ground for their politics and relations. States, with scientists attendant, envisaged and created the grounds for their politics as much as simply finding a patch of earth to control.21

The modern Antarctic order developed because the political settlement of 1959—limited in intent, tied to geophysical sciences, and articulating an almost inert terrain—could not be maintained in the face of changing conceptions of Antarctica or “the environment” more generally. These changing conceptions—arising from continued scientific inquiry, changing global environmental sensibilities, and new geographies of international law and resource exploitation—disrupted the 1959 settlement, providing an opportunity for the treaty’s parties and scientists, both individually and collectively, to advance their interests. The parties assembled an international environment to protect and enhance their own positions; their sense of order; and their stable diplomatic, geopolitical, and environmental relationships.

m odern a n T arc TIc h I s T ory began with the Antarctic Treaty, signed on December 1, 1959.22 Twelve states signed it: Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States. They each had historic ties to the region, with longer or shorter connections through scientific research or whaling and sealing industries; they were also the countries that had participated in the IGY. By signing the treaty they were attempting to ameliorate problems and conflicts that had been troubling their relationships, especially since the end of the Second World War.

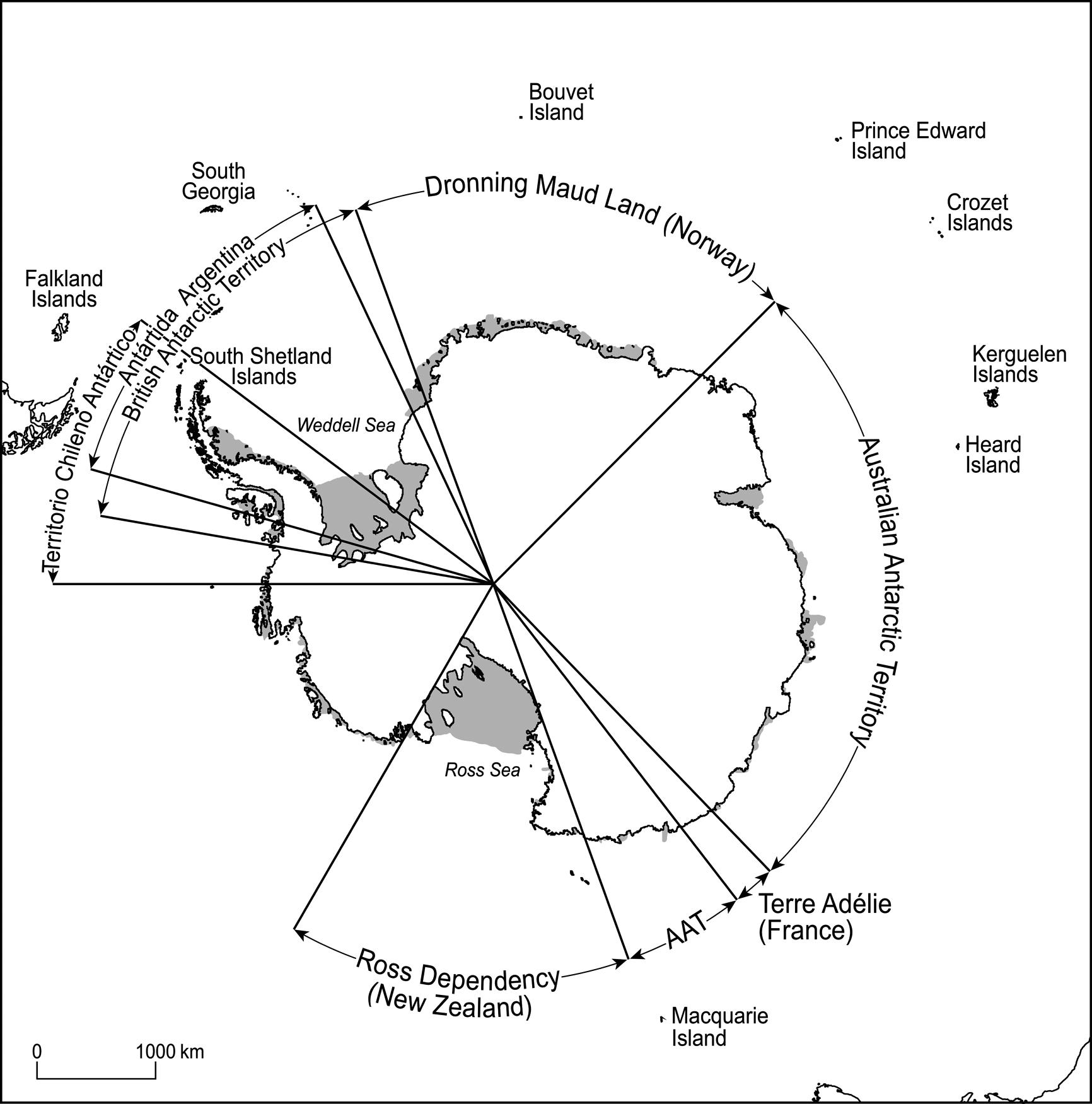

Principal among these problems were the explicit disagreements over the character of territorial sovereignty, the foundational tension of Antarctic affairs. Between 1908 and 1943 seven states claimed territory in Antarctica (see figure I.1). The territorial rush began with the United

Figure I.1 The seven territorial claims to Antarctica. Cartography: Chandra Jayasuriya.

Kingdom’s claim to the Antarctic Peninsula in 1908, followed by claims made by New Zealand in 1923, France in 1924, Australia in 1933, Norway in 1939, Chile in 1940, and Argentina in 1943.23 These claims, however, went generally unrecognized by any other states. Furthermore, the British, Argentine, and Chilean claims to the Antarctic Peninsula region overlapped, and these states lived in a cycle of protest and counterprotest.24 The United States and the Soviet Union quite explicitly reserved the right to make territorial claims.

The second major problem was the tension and suspicion arising from the conflicts and bipolarity of the Cold War. The main concerns came from the Western bloc countries that had witnessed the projection of the Soviet Union into the region; to be sure, the Antarctic was also enrolled in American Cold War-era nationalism.25 While Richard Byrd had represented the United States in the south before the Second World War, laying a basis of territorial claim for the nation in the process, the Soviet Union had injected itself into Antarctic affairs in 1950 when it delivered a bold diplomatic missive to the United States stating that any international agreement on the Antarctic must include the USSR. The Soviet Union declared that owing to “the outstanding contributions of Russian seamen in the discovery of Antarctica”—that is, the global circumnavigation voyage of Bellingshausen, which perhaps first sighted the Antarctic continent in 1820—as well as its whaling activities in Antarctic waters, it could not “recognize as legal any decision regarding the regime of the Antarctic taken without its participation.”26

The third principal challenge was the immense scientific program of the IGY. Occurring between July 1, 1957, and December 31, 1958, the IGY was a worldwide program of scientific research that sought to understand the earth’s geophysical phenomena through concentrated, simultaneous, and synoptic observation and data collection. The geophysical sciences had grown in size and importance in the decade following the Second World War, patronized by the American and Soviet militaries, who were both searching for geophysical knowledge on which to build geostrategic superiority and dominance.27 The IGY brought a significant international scientific program to Antarctica and destabilized traditional geopolitics through the physical activities and presence of scientists from many countries, as well as an ebullient rhetoric of scientific internationalism and the motivating ideals that science and scientists might bring peace and harmony to the world—ironic, given the place of many scientists within national defense and security institutions. The IGY was a transformative

event not only for the geophysical sciences, but also because it exacerbated postwar territorial and Cold War tensions. In a general sense, its tenor of international cooperation destabilized the sense of Antarctica as a space that could be claimed by individual nation-states as sovereign territory. In a more specific way, the IGY was seen by Western countries as allowing, even sanctioning, extensive Soviet activities. It also led to the formation of the principal international body of Antarctic scientists, SCAR, which continues to be the main international scientific forum on Antarctica to this day.28

These apparently intractable disagreements over territorial sovereignty, the threatening and seemingly immovable presence of the Soviet Union, and the powerful discourse of international cooperation through science led the United States in early 1958 to push for an international agreement for Antarctica. An international agreement had been canvassed in 1948, though it was swiftly dismissed. Australia, Britain, and New Zealand had been in discussions with the Americans from late 1957, trying to convince the United States to make a claim to territory and to push for an international agreement excluding the Soviet Union.29 After internal considerations in early 1958, US officials decided not to press a claim but instead to invite the eleven other countries participating in the IGY to a diplomatic conference to negotiate a treaty that would guarantee freedom of scientific investigation and ensure Antarctica would be used for peaceful purposes only. All the states accepted the invitation, negotiating the Antarctic Treaty in two stages: first, in a series of sixty preparatory meetings beginning in June 1958 and then in a formal conference in October and November 1959.

The treaty committed the signatories to several basic principles. It stated that “Antarctica shall be used for peaceful purposes only” and that military activities were prohibited (article I). It also established the principle of “freedom of scientific investigation” and committed the parties to promoting international scientific cooperation among themselves (articles II and III). And it prohibited nuclear explosions and the disposal of radioactive waste (article V). Underwriting these guarantees was article IV, a political compromise on territorial sovereignty, which provided that by signing and acting within the treaty, no state was renouncing its territorial sovereignty, renouncing or diminishing its basis of claim to territorial sovereignty, prejudicing its position of recognition or nonrecognition of territorial sovereignty, or doing anything that could be the basis of a future claim or enlarged claim. Without this article, there would not have

been an agreement. The treaty applied to the land and ice shelf areas south of 60º south latitude, but not the high seas (article VI). To ensure faithful and effective adherence to the treaty, article VII instituted a system of wide-ranging inspection and exchange of information. Finally, the treaty established periodic meetings—later to be called Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings (ATCMs)—“for the purpose of exchanging information, consulting together on matters of common interest pertaining to Antarctica, and formulating and considering, and recommending to their Governments, measures in furtherance of the principles and objectives of the Treaty” (article IX).30

The treaty articulated a limited consensus, with some of the parties seeing a productive internationalized future for the Antarctic under the treaty and others hoping for a circumscribed future of limited activities and minimal engagement. In all of this, the Antarctica of the treaty was a stage for their relationships, rather than a meaningful and constitutive part of them. That the natural and living environment would become central to human concerns in the Antarctic over the following decades was not foreseen when the twelve states signed the treaty.

Concentrating on the text of the treaty can suggest that the signatories covered all potential futures and had reached a perfect or robust consensus. Agreeing to the treaty was a substantial achievement that required serious effort and compromise on all parts. Each party had to consider how its Antarctic past and present could articulate into a future characterized by superpower dominance, checks on pretensions to sovereign territory, and freedom for scientific activities. For some this was a desirable future; for others, it was one to enter only out of necessity, perhaps reluctantly. In the process, the parties agreed to a particular disposition of environment, science, and politics.

Yet there were still other Antarcticas and other politics alluded to in the treaty that were maintained and smuggled through the negotiations to emerge on the other side; the treaty had a complex tangle of histories embedded in it. It therefore developed in ways unexpected or not intended by its negotiators. While sophisticated scholarship has critically explored the links between the IGY and the treaty, there is still a tendency to see all the contemporary issues and successes of the ATS as latent in the negotiations and text of the Antarctic Treaty as written and codified in 1959, which many see as a direct outcome of the IGY.31 This is surely an untenable restriction on critical analyses that might allow a more useful place for history in contemporary Antarctic politics. Understanding Antarctic history during

the treaty era requires careful attention to both internal and external dynamics, not just an eye for the treaty’s apparent self-perpetuation. The dynamic of Antarctic history after 1959 was not simply one set in motion by the treaty, but rather a complex entanglement of worldwide developments with the particularities of Antarctica, a situation of permanent renegotiation and reinterpretation.

The treaty parties could not maintain their particular agreement in the face of changing circumstances in Antarctica and the wider world. The diplomats representing the treaty parties perceived challenges in the 1960s from scientists pushing for a system of nature conservation and from the prospects of renewed exploitation of seals, and in the 1970s from the potential exploitation of minerals and oil and the expanding extraction of marine living resources, especially in the form of krill. In a growing and developing world with finite resources—as well as an increasing sense of, and global discourses on, those limits and scarcity—these pressures to exploit were profound. But the parties also faced changing global environmental sensibilities, a new sense of fragility and interconnectedness between humanity and the natural environment, and new ideas of preservation and respect for the whole earth system—pressures that were equally profound. The greening of Antarctica was a broad trajectory that encompassed a range of actors looking to keep or gain power in a changing world.

With a large and complex cast of actors—twelve states; a variety of scientific institutions, most especially SCAR; individual scientists; and other actors—there were competing ideas about and aspirations for Antarctica. To grasp and elucidate all of them in a work of this scope— considering especially that there were twelve original signatories to the treaty, speaking six languages—would be untenable. Some signatories and actors were more attached, concerned, influential, and dominant than others. While this book relies on the official archives of the four English-speaking parties—Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States, who to be sure had independently formed positions of their own—as well as on other smaller personal and institutional collections, I hope it avoids what Klaus Dodds and Alan Hemmings have labeled “polar orientalism,” a scholarly and political strategy of delegitimizing the ideas and efforts of non-Western and nonEnglish-speaking states.32

Despite the competing ideas, several elements were shared by the actors, both state and nonstate. Following one of the impetuses of the

Antarctic Treaty, each of the treaty parties wanted some version of stability and order. The treaty committed each of the parties to not allow Antarctica to become “a scene of international discord.” In a limited reading, this meant principally that the area below 60° south latitude would remain nonmilitarized and without nuclear weapons and waste. In a more capacious reading it meant that the parties had to cooperate and work together in shaping an international region. “Order” here has several more connotations and resonances than simply an absence of disorder. There was also a search—competing and overlapping among the parties—for an order, a structure of relations, rights, and obligations. In Antarctica a society of states was seeking stability, good and dependable relations, some measure of power, authority, and benefits with obligations.33

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Antarctic states and the community of Antarctic scientists assembled an international environment with particular characteristics. There was an emphasis on the protection of the environment; conservation and sustainable use of natural resources; prevention and mitigation of environmental impacts; the centrality of scientific knowledge and work; an aversion to “discord” and the maximization of “benefit”; and the privileges and centrality of a particular, circumscribed group of actors—all elements that continue to define the contemporary, post-Madrid Antarctic order in various ways. This order was not simply an interstate governance or diplomatic regime; it was made up of a range of environmental, scientific, legal, and geopolitical conceptualizations and ideas relating to Antarctica as much as the codified and formal instruments of international law and diplomacy.34 Furthermore, the order assembled was not simply among state-actors in a society of states. Their order also consisted of a structure of relations with the natural world and of knowledge and conceptions of the natural world.35 As a result, stability and order here meant more than simply geopolitical order; they also included stable, dependable, and anticipatory relationships with the physical and material Antarctic itself, which, as a complex assemblage of geophysical bodies and biological communities, was still being scientifically discovered and revealed throughout this period.

Each actor was also seeking some measure of authority and power, both individually and, when necessary, as a collective. Though dominant popular perceptions depicted a howling wilderness without commercial value, industrialists, entrepreneurs, and state officials saw a rather different Antarctica. Beginning with sealing in the early nineteenth century and continuing with whaling in the twentieth century, many officials and