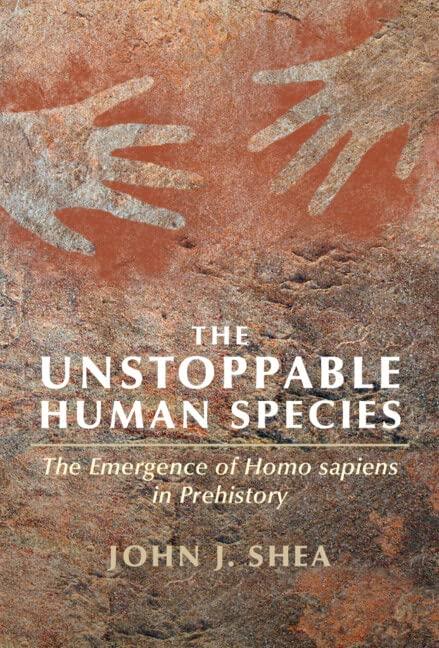

The Formation of Post-Classical Philosophy in Islam

FRANK GRIFFEL

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Frank Griffel 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Griffel, Frank, 1965– author.

Title: The formation of post-classical philosophy in Islam / Frank Griffel. Description: New York : Oxford University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2021009024 (print) | LCCN 2021009025 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190886325 (hardback) | ISBN 9780190886349 (epub) Subjects: LCSH: Islamic philosophy—History.

Classification: LCC B741 .G675 2021 (print) | LCC B741 (ebook) | DDC 181/.07—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021009024

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021009025

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190886325.001.0001

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Integrated Books International, United States of America

für Claudia

Knowledge desired by some may mean ignorance and stagnation for others.

Franz Rosenthal, Knowledge Triumphant (1970)

Denn eigentlich unternehmen wir umsonst, das Wesen eines Dinges auszudrücken. Wirkungen werden wir gewahr . . .

J. W. Goethe, Zur Farbenlehre (1810)

CLASSICAL PHILOSOPHY

ISLAMIC CONTEXT

First Chapter: Khorasan, the Birthplace of Post-Classical

a Land in Decline?

First Half of the Sixth/Twelfth Century: Seljuq Rule

Second Half of the Sixth/Twelfth Century: Khwārazmshāhs and Ghūrids

Patrons: Qarakhanids, the Caliphal Court in Baghdad, and the Ayyubids in Syria

Second Chapter: The Death of falsafa as a Self-Description of Philosophy

Falsafa as a Quasi-Religious Movement Established by Uncritical Emulation (taqlīd)

as Part of the History of the World’s Religions

ikma as the New Technical Term for “Philosophy”

Chapter: Philosophy and the Power of the Religious Law

The Legal Background of al-Ghazālī’s fatwā on the Last Page of His Tahāfut al-falāsifa

Persecution of Philosophers in the Sixth/Twelfth Century

Ayn al-Quḍāt’s Execution in 525/1131 in Hamadan

Shihāb al-Dīn Yaḥyā al-Suhrawardī’s Execution c. 587/1192 in Aleppo

Was al-Ghazālī’s fatwā Ever Applied?

II. PHILOSOPHERS AND PHILOSOPHIES: A BIOGRAPHICAL HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE SIXTH/ TWELFTH CENTURY ISLAMIC EAST

The Principal Sources for Sixth/Twelfth-Century History of Philosophy in the Islamic East

The Early Sixth/Twelfth Century: Avicennism Undisturbed

Avicennism Contested: The Early Decades of the Sixth/Twelfth Century

The Outsider as Innovator: Abū l-Barakāt al-Baghdādī (d. c. 560/1165)

Two Ghazalians of Transoxania: al-Masʿūdī and Ibn Ghaylān al-Balkhī (both d. c. 590/1194)

Majd al-Dīn al-Jīlī: Teacher of Two Influential Philosophers Trained in Maragha

Al-Suhrawardī (d. c. 587/1192), the Founder of the “School of Illumination”

Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī (d. 606/1210): Post-Classical Philosophy Fully Developed

III. THE FORMATION OF Ḥ IKMA AS A NEW PHILOSOPHICAL GENRE

“Philosophical

ḥikma Do: Reporting Avicenna

on Epistemology

What Books in ḥikma Also Do: Doubting and Criticizing Avicenna

Knowledge as a “Relational State”

Knowledge as “Presence”: The Context in al-Suhrawardī

Knowledge as Relation: Abū l-Barakāt al-Baghdādī’s Key Contribution

Knowledge as Relation: Sharaf al-Dīn al-Masʿūdī

Knowledge as Relation: Origins in al-Ghazālī and Avicenna

Do al-Rāzī’s “Philosophical Books” Teach Philosophical Ashʿarism?

Second Perspective: Teachings on Ontology and Theology

A New Place for the Study of Metaphysics within Philosophy

Opposing Avicenna: God’s Essence Is Distinct from His Existence

The Content of God’s Knowledge Understood as Positive Divine Attributes

What Books of ḥikma Mostly Do: Endorsing and Correcting Avicennan Philosophy

Second Chapter: Books and Their Genre

417

The Eclectic Career of al-Ghazālī’s Doctrines of the Philosophers (Maqāṣid al-falāsifa) 428

Al-Ghazālī as Clandestine faylasūf: Evaluating His Maḍnūn Corpus 442

The Maḍnūn Corpus and Forgery: Two Pseudo-Epigraphies Foisted on al-Ghazālī 449

Between Neutral Report and Committed Investment: al-Masʿūdī’s Commentary on Avicenna’s Glistering Homily (al-Khuṭba al-gharrāʾ) 458

Al-Masʿūdī’s Reconciliation of falsafa and kalām on the Issue of the World’s Eternity 467

Post-Classical Philosophy and Tolerance for Ambiguity 471

Third Chapter: Books and Their Method 479

Dialectical Reasoning Replaces Demonstration: “Careful Consideration” (iʿtibār) in Abū l-Barakāt al-Baghdādī 482

The Background of Abū l-Barakāt’s “Careful Consideration” (iʿtibār) 493

The Middle Way between Avicennism and Ghazalianism: How Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī Describes His Philosophy 499

Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī’s Method of “Probing and Dividing” (sabr wa-taqsīm) 506

A Case Study of the New Method: Al-Rāzī on God’s Knowledge of Particulars 518

The Method in Books of ḥikma: Implementing the Principle of Sufficient Reason 524

The Method in Books of kalām: Limiting the Principle of Sufficient Reason 532

Epilogue: Ḥikma and kalām in Fakhr al-Dīn’s Latest Works 543 Conclusions 551

The Formation of Post-Classical Philosophy in the Islamic East during the Sixth/Twelfth Century 562

What Was Philosophy in Islam’s Post-Classical Period? 565

Appendix 1: List of Avicenna’s Students and Scholars Active in the Sixth/Twelfth Century Mentioned in Ibn Funduq al-Bayhaqī’s (d. 565/1169–70) Tatimmat Ṣiwān al-ḥikma (ed. M. Shāfiʿ , 1935) and in Muʿīn al-Dīn al-Naysābūrī’s (d. c. 590/1194)

Itmām Tatimmat Ṣiwān al-ḥikma (MS Istanbul, Murad Molla 1431, foll. 126b–157a) 573

Appendix 2: Relative Chronology of Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī’s Works

Based on Citation Relationships 577 Bibliography 579

Index of Manuscripts 635

General Index 639

Introduction

In September 1683 a large army of soldiers from Germany, Austria, and PolandLithuania won a battle against an even larger Ottoman army that had laid siege to Vienna, the capital of the Holy Roman Empire. That same year, John Locke fled England to the Netherlands and entered into circles that acquainted him with the work of the Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza. In Holland, Locke also found time to work on the manuscript of what would become his most important philosophical work, The Essay concerning Human Understanding, published eventually in London in 1689.

The last two decades of the seventeenth century marked the beginning of two of the most important developments in modern European history: Enlightenment thought and the military defeat of the Ottoman Empire. This was the moment when Europeans started to think of their own history in terms that we now call “modern.” They witnessed history as progress, understood as increasing rationalization and liberalization, as well as the creation of material wealth and the expansion of political power. When Europeans looked at the Muslim world, however, they saw nothing but decline.

From the early Middle Ages, central Europeans had become more and more used to thinking about Islam as Europe’s nemesis, the absolute opposite of all that Europe stood for. By the late seventeenth century, the threat that earlier armies of Muslims had posed to Europe had disappeared. The Turkish siege of Vienna in 1683—the second of its kind after an earlier Turkish attempt in 1526—led to a successful counterattack of central and eastern European armies that conquered, within a few years, almost half of the Ottoman territories on the Balkan. By the end of the seventeenth century, the Habsburg Empire had taken lands from the Turks that are equivalent to the modern countries of Hungary, Croatia, Slovenia, and parts of Romania. Never again would Islamic armies pose a threat to a central European country. Quite the opposite: within only a century a European army stood at the gates of a major Muslim capital and routed its defenders. In July 1798, the French army fought a decisive victory over Egyptian forces during the Battle of the Pyramids. The defeat led to the first European colonial administration of a Muslim country. The Battle of the Pyramids was, however, only the first of many defeats that were inflicted upon almost all Muslim countries in the period between 1798 and 1920. After the Battle of Maysalun before the gates of Damascus in 1920, every Muslim country, with the exception of Turkey, Iran,

The Formation of Post-Classical Philosophy in Islam. Frank Griffel, Oxford University Press. © Frank Griffel 2021. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190886325.003.0001

Afghanistan, and several principalities on the Arabian peninsular, was ruled by Europeans.

Triggered by an increasingly critical attitude toward Western writings on Islam, scholars in the 1990s began to see a connection between the early modern European experience of a continuous progress in their societies and the Western narrative of Islam’s decline. Starting with the seventeenth century, European history was considered a process of advancement and improvement. “Europe’s history, despite all temporary setbacks,” wrote the Danish environmental historian Peter Christensen in 1993, “was characterized by progress, understood as cumulative change for the better in material as well as moral terms.” At the same time Europeans thought of Islam and the Middle East as the opposite of Europe, its inverted reflection. “So it followed logically,” Christensen continued, “that the opposite of progress, decline, must characterize the history of [the] Middle East. With such a premise, it was not difficult to find confirming evidence.”1

The material and moral decline of the region that Europeans diagnosed was ascribed, ultimately, to defects inherent in Muslim society: “The Europeans had come to see progress as a virtual natural process. If a society had not evolved in the same positive way as Europe did, there had to be something wrong with it.”2 One of the postulates of European thinking about the Middle East was that the religion of Islam is so heavily imprinted upon its societies that it can ultimately explain everything that had occurred, or failed to occur. Enlightenment thought also made a close connection between Europe’s rapid political and economic progress during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and the rationalization it was proud to have achieved. The intellectual source of this rationalization was sought in Europe’s tradition of philosophy. Born out of Greek culture in antiquity, Enlightenment thinkers forged a narrative of the history of philosophy in Europe that closely aligned with the cumulative progress that had manifested during their lifetimes. Yet, historians of philosophy such as Edward Gibbon and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel realized that the history of European philosophy was not one of continuous progress. The “dark” Middle Ages stood in the way of an uninterrupted increase of rationality in European thought. Since the reemergence of philosophical activity in Europe during the thirteenth century, however, the story they told about European philosophy was one of uninterrupted progress. If philosophy in Europe progressed, what did it do under Islam?

Together with the narrative of a rise of European philosophy after the thirteenth century came the story of a simultaneous decline of philosophy in Islam. Once, Islam had a great empire and an advanced civilization with cities such as Baghdad and Cairo that had few rivals during their prime. The Islamic Empire

1 Christensen, The Decline of Iranshahr, 9.

2 Ibid.

was seen as the last of the great civilizations of the Middle East and the Abbasid caliphs worthy successors of the pharaohs of Egypt, the kings of Babylon, and the khosrows of Persia. But Arabic high culture was only a very temporary phenomenon. In his Lectures on the History of Philosophy of 1817, Hegel (1770–1831) treated Arabic philosophy not as an independent tradition but merely as one that bridges the Greeks with the scholasticism of the Latin Middle Ages.3 Arabic philosophy, Hegel writes, “has no content of any interest [for us] and it does not merit to be spent time with; it is not philosophy, but mere manner.”4 For Hegel, Arabic philosophy is only the “formal preservation and propagation” of Greek philosophy,5 and has worth only insofar as it is connected to it. The Arabs created no progress in the history of philosophy and “there is not much to benefit from it” (aber es ist nicht viel daraus zu holen).6 Hegel stands at the beginning of the Western academic study of Arabic and Islamic philosophy. He was closely followed by Ernest Renan (1823–92) and his 1852 study, Averroes and Averroism, the first Western monograph on the history of philosophy in Islam.7 French Enlightenment thinking and its enmity toward the Catholic Church heavily influenced Renan’s perspective, leading him to apply categories to the history of philosophy in Islam that were established in the historiography of European thought. For Renan, philosophy in Islam suffered under the persecution of an “Islamic orthodoxy” that would eventually prevail and crush the free philosophical spirit in Islam. Renan wrote in 1861 that with the death of Averroes (Ibn Rushd) in 1198, “Arab philosophy had lost in him its last representative and the triumph of the Qur’an over free-thinking was assured for at least six-hundred years.”8 What relieved the Islamic world from the oppression of a Qur’anic orthodoxy was, in Renan’s mind, the French occupation of Egypt in 1798.

3 Hegel, Vorlesungen über die Geschichte der Philosophie, 19:514–23. See the Engl. transl. in idem, Lectures on the History of Philosophy, 3:26–35.

4 Hegel, Vorlesungen über die Geschichte der Philosophie, 19:517: “Sie ist nicht durch ihren Inhalt interessant, bei diesem kann man nicht stehenbleiben; es ist keine Philosophie, sondern eigentliche Manier.” E. S. Haldane’s translation of 1892 (Hegel, Lectures on the History of Philosophy, 3:29) leaves out this particular sentence.

5 äußerliche Erhaltung und Fortpflanzung; Hegel, Vorlesungen über die Geschichte der Philosophie, 19:514; Lectures on the History of Philosophy, 3:34.

6 Hegel, Vorlesungen über die Geschichte der Philosophie, 19:522; Lectures on the History of Philosophy, 3:26.

7 In the decade before Renan, two important studies of philosophy in Islam had already appeared. Solomon Munk (1803–67) wrote several articles on Arabic philosophers, both Jews and Muslims, for the six-volume Dictionnaire des sciences philosophique, published 1844–52. These articles were later incorporated into Munk, Mélanges de philosophie juive et arabe (1857–59). In 1842, August Schmölders (1809–80) published his Essai sur les écoles philosophiques chez les Arabes, which is an edition and annotated French translation of al-Ghazālī’s al-Munqidh min al-ḍalāl.

8 Renan, Averroès et l’averroïsme (2nd augmented edition), 2. In the first edition of 1852 (1) this sentence did not yet have its colonialist second half: “Quand Averroès mourut, en 1198, la philosophie arabe perdit en lui son dernier représentant.” In the second edition of 1861, Renan adds “et le triomphe du Coran sur la libre pensée fut assuré pour au moins six cent ans.”

Enlightenment thought provided the legitimization for colonizing the Muslim world. Europeans convinced themselves that the decline they diagnosed in the Muslim world after their military successes in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries had set in much earlier and that it was connected to an assumed absence of philosophy in Islamic societies. European historians of philosophy created the narrative that Arabic and Islamic philosophy ended with Averroes during the last years of the twelfth century. The Dutch historian of philosophy Tjitze J. de Boer (1866–1942) was the first to write a textbook on the history of philosophy in Islam. It came out in German in 1901, with an English translation in 1903, and remained influential for many decades, up until the 1990s.9

De Boer’s presentation of Arabic and Islamic philosophy ends with Averroes, who is followed only by a brief appendix on Ibn Khaldūn. Averroes was the peak of the philosophical tradition under Islam. His commentaries on the works of Aristotle were regarded as the most profound philosophical works produced by that tradition. Yet with him ended philosophy in Islam, and with him also began the rise of Aristotelian and thus scholastic philosophy in Europe. Averroes was the link that connected the progress of European philosophy with the decline of the philosophic tradition in Islam. Already in his book Averroes and Averroism, Renan had come up with the view that European philosophers valued the quality of Averroes’s scholarship, whereas Muslims neglected it at their own peril.10

Historians like Renan and de Boer in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were working with far fewer sources than what we have available today. Their decision to exclude a host of philosophers who wrote after Averroes from the history of this discipline, however, is not based on ignorance about their existence. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when Europeans started to explore the history of Arabic and Islamic philosophy, they knew otherwise. The books produced in this period had not yet adopted a colonialist perspective on Islam and the Middle East and are free from the idea that philosophy in Islam had ever ended. In 1743, for instance, the German scholar Johann Jacob Brucker (1696–1770) published a six-volume history of philosophy in Latin (Historia critica philosophiae), which includes more than two hundred pages on Arabic and Islamic authors. Here, readers could find relatively long articles on Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī (d. 606/1210) and Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (d. 672/1274). Brucker mentions numerous authors of philosophy who wrote during Islam’s post-classical period, and this despite the fact that unlike Renan and de Boer, he

9 De Boer’s Geschichte der Philosophie im Islam was translated into English (1903), Persian (1927), Arabic (1938), and even into Chinese (1946). The English translation was reprinted in London 1933, 1961, and 1965; in New York 1967; in New Delhi 1983; and in Richmond (Surrey) 1994. The Chinese version was reprinted as late as 2012.

10 Renan, Averroes et l’averroïsme, 28 (1st edition).

read no oriental languages.11 A similar picture emerges from the monumental four-volume work Bibliothèque orientale, published at the end of the seventeenth century in Paris. It was generated under the leadership of the French orientalist Barthélemy d’Herbelot (1625–95) and is a forerunner to the large encyclopedias of the French Enlightenment. The Bibliothèque orientale is based on an Arabic encyclopedia of the sciences that had appeared fifty years earlier, namely Kātib Çelebī’s (d. 1067/1657) Disclosure of Opinions about the Sciences and Their Books (Kashf al-ẓunūn ʿān asāmī l-kutub wa-l-funūn). Kātib Çelebī was well acquainted with the major achievements of post-classical philosophy in Islam. Hence, the Bibliothèque orientale is full of information about philosophers such as Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī, Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī, the Iranian Mullah Ṣadrā (d. 1050/1640), and the Ottoman Turk Kamālpashazādeh (d. 940/1534) and their most important works.12

In the nineteenth century, however, that information got lost in a narrative of decline. De Boer saw the reason for the decline of philosophy in Islam in the works of al-Ghazālī. The most knowledgeable and influential Western authorities in Islamic studies, such as Ignác Goldziher (1850–1921), Hellmut Ritter (1892–1971), and Edward Granville Browne (1862–1926), taught that al-Ghazālī’s book The Precipitance of the Philosophers (Tahāfut al-falāsifa) had ushered in the end of philosophy in Islam.13 Al-Ghazālī was, as Browne wrote in 1906, “the theologian who did more than any one else to bring to an end the reign of philosophy in Islam.”14 After al-Ghazālī, and here I quote de Boer’s textbook, there were only “epitomists” in the Eastern Islamic world. Philosophers they were, de Boer acknowledges, but of a philosophy that was in decline, and “in no department did they pass the mark which had been reached of old: Minds were now too

11 Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī appears under the name of “Ibnu El-Chatib Rasi” and al-Ṭūsī as “Nasiroddinus”; see Brucker, Historia critica philosophiae, 3:113–18. Other post-classical authors mentioned are Abū l-Barakāt al-Baghdādī (“Ebn Malca”) and al-Taftazānī (“Ettphtheseni”) (3:119–20).

12 Cf. d’Herbelot, Bibliothèque orientale, 3:116–17 on Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī, and 2:684 on his work al-Muḥaṣṣal and its commentary by al-Kātibī al-Qazwīnī (2:642, 1:527); further the articles on Abū l-Barakāt al-Baghdādī (2:223), Athīr al-Dīn al-Abharī (1:21), Quṭb al-Dīn al-Rāzī (3:118), or Naṣīr al-Dīn aṭ-Ṭūsī (3:26) and his work Akhlāq-i Nāṣirī (3:27) as well as his Tajrīd al-ʿaqāʾid and its numerous commentaries (3:385–86). Finally, see the interesting article on the science of ḥikma (2:233–34).

13 Goldziher, “Die islamische und die jüdische Philosophie des Mittelalters,” 63–64; Vorlesungen über den Islam, 177–78, 198; Engl. transl. 158–59; Ritter, “Hat die religiöse Orthodoxie einen Einfluß auf die Dekadenz des Islams ausgeübt?,” 121, 134. I follow Alexander Treiger, Inspired Knowledge, 108–15, in his argument that the commonly accepted translation of tahāfut as “incoherence” is wrong. The verb tahāfata means something like “to rush headlong into a seemingly beneficial but ultimately dangerous situation,” almost like a moth that rushes toward the fire. Already in 1888, Beer, Al-Ġazzâlî’s Maḳâṣid al-Falâsifat, 6, translated tahāfut as “blindly running after someone or a group who runs fast and recklessly ahead,” “run into error.”

14 Browne, A Literary History of Persia, 2:293.

weak to accomplish such a feat. . . . Ethical and religious doctrine had ended in Mysticism; and the same was the case with Philosophy.”15

Those who work in Islamic studies know that the view of al-Ghazālī as the destroyer of philosophy in Islam is still very much alive, particularly in more popular publications of our field. Today seemingly respectable publications still present him as the final point of any discussion of philosophy in Islam,16 not to mention the many polemical voices on the internet that fuel and are fueled by sentiments of Islamophobia.17 Among those who work actively in the field of the history of philosophy in Islam, however, al-Ghazālī’s assessment has drastically changed in the past thirty years. He is no longer regarded as the destroyer of philosophy in Islam. We now understand that his major response to the philosophical movement in Islam, The Precipitance of the Philosophers (Tahāfut alfalāsifa), is a complex work of refutation and is not aimed at rejecting philosophy or Aristotelianism throughout. It is concerned with twenty teachings developed by Aristotelian philosophers in Islam, and it vigorously rejects at least three of them, to the extent that it declares those philosophers who uphold these three teachings apostates from Islam and threatens capital punishment. The book, however, does not reject philosophy as a whole. In fact, it can be read—and it was read—as an endorsement of studying Aristotelianism to find out what is correct and what is wrong among the teachings of Muslim Aristotelians. In that sense, the book is a demarcation between those teachings of Arabic Aristotelianism that al-Ghazālī deemed fit to be integrated into Muslim thought and those he thought unfit.18

The reevaluation of al-Ghazālī’s Tahāfut al-falāsifa as a work that is not directed against philosophy but aims to create and promote a different kind of philosophy from that it criticizes is seconded by an earlier development in the field of

15 De Boer, Geschichte der Philosophie im Islam, 151; Engl. trans. 169–70. This opinion is, for instance, echoed by F. E. Peters, who wrote in 1968, “Ibn Sīnā’s disciples descended . . . into a faceless mediocrity. . . . Both Abū al-Barakāt (d. a.d. 1165) and ʿAbd al-Laṭīf al-Baghdādī (d. a.d. 1231) are still worthy of the name of faylasuf, but the rest, if it is not silence, is not much more than a whisper” (Aristotle and the Arabs, 230–31).

16 A recent example from 2014 is, for instance, the presentation of al-Ghazālī in Starr, Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia’s Golden Age From the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane, 406–22. According to Starr, al-Ghazālī was “the dark genius” (532), who taught that “Aristotle’s logic is totally irrelevant to revealed religion,” regarded any talk of causality as “quackery and fraud,” and thus “gave his students an excuse for ignoring . . . the difficult studies” connected with the rational sciences (414, 417). “Convinced that he was in possession of divine truth, [al-Ghazālī] proceeded to pass judgment on all those who, in his view, were not” (419) and branded all philosophers and freethinkers as apostates. “In doing so, Ghazali administered the coup de grâce” to philosophy and the sciences (419). A hundred years later his “denunciation of science and philosophy had long . . . become a bestseller,” and “never again would open-ended scientific enquiry and unconstrained philosophizing take place in the Muslim world without the suspicion of heresy and apostasy lurking in the air” (422).

17 Examples are lectures by Neil deGrasse Tyson on the history of science in Islam that are widely available on sites such as YouTube.

18 For more on al-Ghazālī’s strategy see pp. 81–84 and 479–82 in this book.

Ghazālī studies. Two important articles were published more than thirty years ago, in 1987, Richard M. Frank’s (1927–2009) “Al-Ghazālī’s Use of Avicenna’s Philosophy” and Abdelhamid I. Sabra’s (1924–2013) “The Appropriation and Subsequent Naturalization of Greek Sciences in Medieval Islam.” Frank’s article launched a whole new direction of research on al-Ghazālī. Earlier Western contributions on him highlighted his critical attitude toward the teachings of al-Fārābī (d. 339/950–51) and Avicenna (Ibn Sīnā, d. 428/1037). After Frank’s article and a more thorough monograph published in 1992,19 books and articles appeared that investigate what al-Ghazālī had adopted from falsafa. This has become the dominant direction of Ghazali studies in the past twenty years. Important books and articles made the case that many of his most original teachings are adaptations of earlier ones by Avicenna. By adaptation we do not mean that they are therefore no longer original to al-Ghazālī. Rarely did he adapt something from Avicenna without making changes. Often these were slight changes in wording that amounted nevertheless to significant philosophical and theological permutations. In his autobiography al-Ghazālī points out that the skilled expert produces the antidote to a snake’s venom from the venom itself.20

Sabra’s article offers context for Frank’s discoveries, showing that al-Ghazālī’s adaptation of teachings from Avicenna and al-Fārābī was part of a much larger phenomenon in Islam. Sabra observed that by the eighth/fourteenth century, sciences that were earlier called Greek and regarded as foreign had, in fact, become Muslim sciences. For Sabra this happened in a two-step development of first appropriating Greek sciences in a process of translation and adaptation to a new cultural context, characterized by the use of the Arabic language and a Muslim-majority culture, and second by naturalizing them so that the Greek origins of these sciences were no longer visible. Although he did not work with Sabra’s categories, Frank’s contributions of 1987 and 1992 can easily be corresponded to Sabra’s suggestions. Whereas Avicenna’s philosophy is an expression of the process of appropriation in which the Greek origins of many of his teachings are clearly visible and even stressed, al-Ghazālī, who adopted and adapted many of Avicenna’s teachings, obscured their origins and thus contributed to—or maybe even initiated—the process of naturalization. Sabra himself never applied his suggestion to the fate of philosophy in Islam. It is, however, a very fitting description of what happened during the sixth/twelfth century and after. The movement of falsafa can thus be regarded as the continuation of Greek philosophy in Arabic. As Sabra’s work foregrounds, falsafa represents the appropriation of a Greek science in Islam. Subsequently, the appropriated Greek

19 Frank, Creation and the Cosmic System.

20 al-Ghazālī, al-Munqidh, 25.19–24, 27.7–24. On that passage see al-Akiti, “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly,” 87–88.

science of philosophy becomes naturalized as ḥikma. The work of al-Ghazālī is, in fact, the beginning of the naturalization process of Greek philosophy in Islam.

In some of my earlier works, particularly Apostasie und Toleranz im Islam, published in 2000, on the development of the judgment of apostasy in early Islam, I tried to make the case that al-Ghazālī cannot be made responsible for the disappearance of philosophy in Islam. In this book I advance on closer inspection a different argument: philosophy did not disappear after al-Ghazālī. In fact, the period after al-Ghazālī is full of philosophical works, even if adhering to most narrow standards of what counts as philosophy. The existence of philosophy after al-Ghazālī is so obvious that we must ask how it could have been overlooked for so long. Did earlier generations of intellectual historians—including my earlier self—not see that there was a thriving philosophy after al-Ghazālī? Some did. The German scholar Max Horten (1874–1945), who after 1913 held various professorial positions at universities in Bonn and Breslau, understood the importance of several Arabic works of post-classical philosophy that were printed in Cairo at the beginning of the twentieth century. He started to paraphrase and analyze them and thus became the first European expert on this kind of literature.21 Horten, however, insisted on translating the Arabic technical terminology of these books into words that he thought his readers could relate to. He chose terms from Latin medieval philosophy and hence obscured the teachings and the originality of post-classical philosophy in Islam. Horten also failed to connect the texts to their context. This and the fact that his German paraphrases did not reach the philological standards of recent works by Goldziher and others confirmed an earlier impression—voiced by de Boer and others—that post-classical philosophy in Islam is repetitive and arid.

The breakthrough in this field is happening only now. It is the result of several factors, some of which I will discuss in this book. A proper understanding of the continuity of philosophy in Islam will not be achieved unless one realizes the crucial error that many intellectual historians of Islam have committed— and that not a small number of them still commit today: for the period after the mid-sixth/twelfth century, the Arabic word falsafa no longer represents the full range of what in English is referred to as “philosophy,” in German as Philosophie, or in French as la philosophie. All these words have their origin in the Greek word philosophía. Identical etymology, however, does not guarantee identical meaning.

At the beginning of this book project stands the realization, shared by almost everybody who works in this field, that al-Ghazālī’s Tahāfut al-falāsifa is a work of philosophy. This may sound like a trivial insight that even earlier researchers

21 On Horten’s work see pp. 310–12.

such as de Boer indeed shared.22 The full implications for the history of philosophy in Islam, however, have yet to be drawn. Even very recent contributions to the history of Arabic and Islamic philosophy contain statements saying that alGhazālī launched attacks “against philosophy in general, and metaphysics in particular.”23 This, however, gives the wrong impression that his attacks had come from outside of philosophy. The quoted sentence excludes al-Ghazālī from the history of philosophy and suggests that he was hostile to rational inquiry and the advancement of knowledge through reasonable and convincing arguments. That was Renan’s view of al-Ghazālī. Renan taught that philosophy in Islam was attacked by outsiders like him who aimed at squashing it in the name of Islamic orthodoxy. In reality, what we see happening at the turn of the sixth/twelfth century is the development of a philosophical dispute between those who defended Avicenna’s teaching on God and His relation to this world (the falāsifa) and the likes of al-Ghazālī who criticized this position.24

Thinkers who followed al-Ghazālī in his criticism of falsafa were also engaged in philosophy and should be regarded as part and parcel of the history of philosophy in Islam. They must count as active contributors to the history of philosophy in Islam, as philosophers, albeit not falāsifa. This leads to the next important realization: after al-Ghazālī, philosophy in Islam was not the same as Arab Aristotelianism. In his Tahāfut al-falāsifa, al-Ghazālī uses the word falsafa to describe the kind of Aristotelianism that is taught in the books of Avicenna, among them his most comprehensive work, The Fulfillment (al-Shifāʾ).25 Almost all philosophers writing in Arabic and Persian—Muslims, Christian, as well as Jews—who came after al-Ghazālī adapted this choice of language.26 Beginning with the Tahāfut al-falāsifa, which was published in 488/1095,27 the word falsafa was understood in Arabic and Persian as a label for the philosophical system of Avicenna as well as for the teachings of al-Fārābī and other earlier philosophers wherever they are congruent with those of the Eminent Master

22 De Boer, Geschichte der Philosophie im Islam, 138–50; Engl. trans. 154–68, has a full chapter on al-Ghazālī.

23 Amos Bertolacci in his online article “Arabic and Islamic Metaphysics” in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/arabic-islamic-metaphysics/, accessed June 16, 2020), first published in July 2012.

24 This study does not close its eyes to the fact that one of these two philosophical parties tries to use institutional power in the form of a religious authority to defeat the other. The point is discussed in chapter 3 of the first part of this book.

25 “Fulfillment” seems a more accurate translation of the title of Ibn Sīnā’s main work than the oft-used “Cure” or “Healing.” See Saliba, “Avicenna’s Shifāʾ (Sufficientia),” and Nusseibeh, Avicenna’s al-Shifāʾ , xv.

26 Ibn Rushd was one of the few Arabic authors who did not adopt al-Ghazālī’s choice of language in his Tahāfut and who argued that by focusing on Ibn Sīnā, al-Ghazālī misrepresented the movement of falsafa and neglected its various non-Avicennan elements. Ibn Rushd was also one of a small number of philosophers after al-Ghazālī who claimed for himself the label of being a faylasūf

27 See p. 417.

(al-shaykh al-raʾīs) Avicenna. Or, in simpler terms: starting with al-Ghazālī’s Tahāfut, the Arabic (and Persian) word falsafa meant Avicennism. Yet Avicenna’s philosophy—as has just been pointed out—was not the only philosophy that was practiced during the sixth/twelfth century and after. De Boer’s mistake—and that of many other Western historians of philosophy who followed—was to identify philosophy in Islam with falsafa. This, however, would be—to use a drastic example—like equating Western philosophy in the twentieth century with Marxism. It may be true that in some corners of the twentieth-century world, such as the Soviet Union, all the philosophy that was practiced was Marxist. But that would still not allow historians to limit the history of Western philosophy in the twentieth century to that particular direction. Reducing the history of philosophy in Islam to falsafa contributed to the diagnosis of its demise soon after al-Ghazālī’s Tahāfut. This reduction led with equal consequence to the neglect of those philosophical traditions that depart from falsafa.28 Only once we realize that philosophy in Islam was something much bigger than falsafa just as twentieth-century Western philosophy was much bigger than Marxism—can we attempt to write a true history of philosophy in Islam.

This book wishes to make a step in that direction. It will try to answer the question of what philosophy was in the eastern parts of the Islamic world during the sixth/twelfth century. It makes the case that in addition to what was then called falsafa, there existed in the sixth/twelfth century other important traditions of philosophy. One was the tradition that was founded by al-Ghazālī’s Tahāfut al-falāsifa; another was the philosophical project of Abū l-Barakāt alBaghdādī (d. c. 560/1165); and a third and fourth are represented by the œuvres of Yaḥyā al-Suhrawardī (d. c. 587/1192) and Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī (d. 606/1210). All four directions of philosophy positioned themselves vis-à-vis the philosophy of Avicenna.

One of the most important philosophical differences between Avicenna and al-Ghazālī was their opposing teachings on God and His attributes. Influenced by Neoplatonic arguments about God’s unity, Avicenna developed a philosophical theology—meaning a theology that is wholly based on rational arguments without any recourse to revelation—where God acts out of the necessity of His being, which must be wholly one. This implies that, first, Avicenna’s God cannot change and, second, He acts without exercising a free choice between alternative actions. The first point implies that God cannot change from being a noncreator to becoming a creator. This results in Avicenna’s teaching of a pre-eternal world. In his Tahāfut al-falāsifa, al-Ghazālī attacks this set of teachings by Avicenna and argues that a pre-eternal world is impossible. This, in turn, leads to the

28 I pointed this out in the commentary to my German translation of Ibn Rushd’s Faṣl almaqāl, 61–65.

conclusion that God must be able to change from noncreator to creator and that He must have a free will and does exercise choice between alternatives.

This major difference between the thoughts of Avicenna and al-Ghazālī forms the backbone of any understanding of philosophy in the Islamic East during the sixth/twelfth century. Avicenna’s Creator-God is what in the context of the Western Enlightenment has been called the “God of the philosophers.” The phrase is ill-placed in Islam, as it refers to a group of mostly French public intellectuals of the eighteenth century who had chosen the label les philosophes to distinguish themselves as thinkers who were independent of any commitment to Christianity and its Church. Still, their thoughts about God can help us illustrate and understand Avicenna’s ideas about God. Many Enlightenment thinkers, and among them many of the French philosophes, were committed to a deist understanding of God that developed in Europe in the wake of Baruch Spinoza’s (1632–77) philosophy. The connections between Avicenna’s thought and that of Spinoza are highly interesting, but they go beyond the scope of this book. Suffice to say, Spinoza had access to Hebrew philosophical texts—such as those of Maimonides (d. 601/1204), for instance—that were deeply influenced by falsafa. 29 According to a simplified deist understanding, God is the creator of the world, but He cannot interfere in it. God creates the rules that govern causal connections— what we today might call the “laws of nature” or “laws of physics”—through which He governs over His creation. Hence, God creates through the intermediation of long chains of secondary causes, whereby each creation becomes the intermediary for the next creation that it causes. God, however, does not choose these “laws of nature” that govern this process of creation by secondary causes. Rather, God Himself is governed by the necessity that these “laws” express.

Avicenna developed a highly impersonal understanding of God whereby the deity—who in his œuvre is most often referred to as “the First Principle” or “the First Starting-Point” (al-mabdaʿ al-awwal)—never exercises a decision or a choice about what to create. In Avicenna’s understanding, God is the origin of all necessity that exists in this world, most importantly the necessity that governs causal connections and hence determines this world. A simplified but not inaccurate expression of Avicenna’s understanding of the deity would be to say that God is the laws of nature that govern His creation. He does not choose them, but He is them. Avicenna never would have chosen such language since he didn’t think in our modern terms of “laws of nature.”30 Rather, for Avicenna, God is

29 See, for instance, Fraenkel, Philosophical Religions from Plato to Spinoza, or W. Z. Harvey, “A Portrait of Spinoza as a Maimonidean.”

30 For Ibn Sīnā, what we call “laws of nature” are enshrined in the “constituents” (muqawwimāt) and the “concomitants” (lawāḥiq) of the quiddity (māhiyya) of a certain species. “Combustible if touched by fire,” for instance, is one of the passive concomitants of the species cotton, and “igniting” an active concomitant of fire. Once fire and cotton come together, these concomitants lead to a necessary causal reaction.

pure necessity—He is the being necessary by virtue of itself (wājib al-wujūd bidhātihī)—meaning He is the reason for how all other things must be.31 These “other things” are the beings that are necessary by virtue of something else (wājib al-wujūd bi-ghayrihī), namely by virtue of God. Once modern European philosophy understands the necessary as being expressed by laws of nature, it is only a small step from Avicenna’s understanding of God as necessity to Spinoza’s deus sive natura (God, meaning Nature).

If creation is an expression of the necessity that God is, then creation must last as long as God lasts, which is from past eternity. This latter implication offered al-Ghazālī the philosophical angle to criticize Avicenna’s conceptualization of God. For al-Ghazālī, the God of Avicenna was not the God that is described in the Muslim revelation. Motivated by his commitment to Ashʿarite Muslim theology, al-Ghazālī found in revelation an active God who chooses to create this world among an almost infinite number of alternative ones. God’s will (irāda) and His choice (ikhtiyār) are the two cornerstones of al-Ghazālī’s understanding of the divine. He faced the problem, however, that Avicenna did not deny that God has a will and a choice, even if he meant different things with these words than al-Ghazālī did. Rather than quibbling with Avicenna over the meaning of divine attributes, al-Ghazālī chose to attack the falāsifa’s understanding of the divine via the implication of a pre-eternal world. If he could show that a world without a beginning in time is impossible and that, for instance, an infinite number of moments could never have existed in the past, then al-Ghazālī would have refuted Avicenna’s understanding of God. Without the possibility of a preeternal world, there would need to be a decision on the part of God to start creating. If there was that first decision about creation, many other decisions and many other choices could follow.

While arguments about the eternity of the world were one of the philosophical battlegrounds of the conflict between Avicenna and al-Ghazālī, the conflict itself was about two different understandings of God. It would, however, be wrong to say that one party in this conflict stood on the side of revelation—or worse: religion—and the other on the side of philosophy. Given that the conflict was about our human understanding of God, it should be clear that both parties were engaged in a process of religious thinking or, if one wants, in thinking about religion. Producing his arguments against Avicenna, al-Ghazālī was certainly motivated by his Ashʿarite reading of Muslim revelation. Avicenna, however, had also developed an understanding of revelation that was perfectly in line with his conceptualization of God. In several of his works Avicenna writes commentaries

31 ma ʿnā wājib al-wujūb bi-dhātihī annahū nafs al-wājibiyya. Ibn Sīnā, al-Taʿlīqāt, 50.23 / 121.9; see also idem, al-Mubāḥathāt, 140.10, 142.3 (§§ 386, 391), which are quoted in al-Rāzī, al-Mabāḥith, 1:122.5, 123.7.

on verses and short suras of the Qur’an.32 Although he never expressed it explicitly, we have good reason to assume that Avicenna considered his understanding of revelation and his conceptualization of God a sound expression of Islam and just as Islamic as many contemporary views, including the Ashʿarite one. What’s more, we should understand that Avicenna thought of his interpretation of Islam and its revelation as truth. For him, other Muslim groups, such as the Muʿtazilites and Ashʿarites, had failed to reach that truth. The clash was not between “revelation” and “philosophy” but rather between different readings of revelation and between different ways of arguing philosophically.

During the sixth/twelfth century, that is, during the century after al-Ghazālī’s philosophical intervention, there were philosophers who followed Avicenna just as there were those who followed al-Ghazālī. What is most curious, however, and what prompted me to write this book, is the observation that less than a hundred years after al-Ghazālī, in the last quarter of the sixth/twelfth century, we find authors who write one set of books that defend Avicenna’s understanding of God and another set that defend al-Ghazālī’s. Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī was the first author, as far as I can see, who composed works in kalām (rational theology) where he followed in al-Ghazālī’s footsteps to criticize Avicenna and others in ḥikma (philosophy), where he aimed at improving the philosophical system of Avicenna. To be clear: the former set of books argues for different conclusions from the latter ones. This study will trace the emergence of books on ḥikma from al-Ghazālī, where we find the first seeds of this genre, to its fully developed form in Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī.

The main thesis of this book is that authors of post-classical philosophy such as Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī wrote books in the discipline of philosophy (ḥikma) that are conscious in their continuation of the discourse of falsafa in Islam while also writing books in the discipline of rational theology (kalām) that are part of a different genre of texts and follow different discursive rules. Al-Rāzī was the first of a line of thinkers who in their works of ḥikma defended some of the teachings of Avicenna, yet in their books of kalām defended Ashʿarite teachings on the same subjects. While there are some areas of thought where Avicennism and Ashʿarism are quite compatible with one another—cosmology, the theory of human acts, for instance, or ethics—they are at loggerheads when it comes to the conceptualization of God and His attributes. Here, there is no middle ground between Avicennism and Ashʿarism, and by extension between the results of ḥikma and kalām. Indeed, we see that works in these two genres argue for directly opposing conclusions on such subjects as the world’s pre-eternity and the closely

32 See the texts gathered in ʿĀṣī, al-Tafsīr al-Qurʾānī wa-l-lugha al-ṣūfiyya fī falsafat Ibn Sīnā, and, based on that, Janssens, “Avicenna and the Qurʾān,” and de Smet and Sebti, “Avicenna’s Philosophical Approach to the Qur’an.” See also Janssens, “Ibn Sīnā (Avicenna).”

related subject of divine essence and divine attributes, particularly God’s will and His choice. And yet, these two different sets of books were written by the same authors! Fakhr al-Dīn’s younger contemporary Sayf al-Dīn al-Āmidī (d. 631/ 1233) wrote books in ḥikma (al-Nūr al-bāhir and Kashf al-tamwīhāt) and books in kalām (Abkār al-afkār and Ghāyat al-marām) where the same phenomenon of opposing conclusions can be observed. In the next generation, Athīr al-Dīn alAbharī’s (d. 663/1265) Guide to Philosophy (Hidāyat al-ḥikma) was one of most successful textbooks of ḥikma, attracting many commentaries that show how it was adopted to madrasa curricula. Yet al-Abharī also left us a book on kalām (Risāla fī ʿilm al-kalām). Another example is Shams al-Dīn al-Samarqandī’s (d. 722/1322) highly successful textbook of techniques and strategies in disputations (al-Risāla fī ādāb al-baḥth wa-l-munāẓara), which assumes that there were different ways of arguing in ḥikma and in kalām and which provides different sets of examples for these two genres.33

The distinction between works of ḥikma and those of kalām becomes well established in the seventh/thirteenth century, and while this question lies outside the focus of this monograph, it seems to have existed continuously until the nineteenth century, when the curricula of madrasa education in Islamic countries were replaced by those of newly founded European-style polytechnics and universities. If anything, these new institutions destroyed post-classical philosophy in Islam. Its home was the madrasa, which financed its activities out of the revenues of pious endowments (sing. waqf or ḥubus) of land and real estate. No uprising of nomadic Turkmen nor the devastations of the Mongol conquest caused as much damage to this educational system and to the continuity of an indigenous philosophical tradition in Islam as a single law that abolished the endowments of the madrasas or that simply privileged personal private property over waqf and ḥubus landownership. Yet these laws were passed in countless Muslim countries during the period of Western colonization. Rather than any single Muslim opponent of falsafa, it seems that colonial domination and a Muslim eagerness to catch up with the economic and intellectual developments of the West caused the end of the kind of philosophical discourse explored in this book.

Another way of presenting the goal of this study is to say that it tries to explain Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī’s two early philosophical compendia, The Eastern Investigations (al-Mabāḥith al-mashriqiyya) and The Compendium on Philosophy and Logic (al-Mulakhkhaṣ fī l-ḥikma wa-l-manṭiq). These are puzzling works that present a philosophical system that, on the one hand, follows Avicenna and, on the other hand, tries to alter and improve him. Why, however, would

33 al-Samarqandī, al-Risāla fī ādāb al-baḥth, 88–91. For the centrality of this work and its content, see Belhaj, “Ādāb al-baḥth wa-al-munāẓara.”

the Muslim theologian Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī, author of a massive Qur’an commentary and many successful books on Ashʿarite kalām, aim to improve the system of Avicenna’s philosophy, a philosophy that al-Ghazālī in his Tahāfut alfalāsifa had condemned as unbelief and apostasy from Islam? Earlier literature on Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī has mostly avoided dealing with the problem that these two books pose. Muḥammad Ṣāliḥ al-Zarkān (1936–2013), the author of a very impressive early monograph study on Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī, published in 1971, dismissed his Eastern Investigations as an “early work, where al-Rāzī got carried away over and above the falāsifa.” Given that in all of the other works of Fakhr al-Dīn that al-Zarkān examined closely he wrote like an Ashʿarite mutakallim, this one book should be dismissed as youthful folly. Later, al-Zarkān says, alRāzī’s positions developed into those put forward in his books on kalām 34 That line of argument was taken either explicitly or implicitly by many scholars who tried to establish a consistent set of teachings in Fakhr al-Dīn’s œuvre. This line, however, is closed to us since Eşref Altaş’s 2013 study on the chronology of alRāzī’s corpus. Altaş shows that Fakhr al-Dīn started his career with a short book in kalām, followed by his Eastern Investigations, when he was still in his late twenties. This was followed by his most influential book in kalām, The Utmost Reach of Rational Knowledge in Theology (Nihāyat al-ʿuqūl fī dirāyat al-usūl). All these works precede al-Rāzī’s Compendium on Philosophy and Logic his second major book in ḥikma which was completed in 579/1184, when he was thirtythree years old.35 Should we assume that Fakhr al-Dīn started his career as an Ashʿarite mutakallim, then drifted toward defending Avicenna’s philosophy, only to return to being an Ashʿarite, and then once again falling for the temptations of Avicenna? Such drastic reversals of opinion are implausible even for such a flamboyant and self-confident thinker as Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī.

We must therefore accept that Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī and with him the tradition of post-classical philosophy in Islam were in one way or another committed to the teachings of both ḥikma and of Ashʿarite kalām. Which way exactly will be one of the questions this study must answer. What prompted Fakhr al-Dīn— and with him al-Āmirī, al-Abharī, al-Samarqandī, and many others—not only to present the Avicennan philosophical system in over 1,500 pages but also to alter and improve upon it? What were those improvements, and how should we think about them? Finally, what does this mean for our view of the history of philosophy in Islam? Was Fakhr al-Dīn’s engagement with philosophy merely an academic exercise, and was de Boer correct when he suggested more than a hundred years ago that books such as al-Rāzī’s Eastern Investigations were the idle

34 al-Zarkān, Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī wa-ārāʾuhū al-kalāmiyya wa-l-falsafiyya, 299–300, 301. The book represents a master’s thesis at Cairo University that was completed in 1963 and published, apparently without much revision, around 1971.

35 Altaş, “Fahreddin er-Râzî’nin eserlerinin kronolojisi,” 97–113.