The First Episode of Psychosis

A Guide for Young People and Their Families

Revised and Updated Edition

Beth Broussard and Michael T. Compton

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America. © Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Broussard, Beth, author. | Compton, Michael T., author.

Title: The first episode of psychosis : a guide for young people and their families / Beth Broussard., Michael T. Compton

Description: Revised and Updated edition. | New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020026338 (print) | LCCN 2020026339 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190920685 (paperback) | ISBN 9780190920708 (epub) | ISBN 9780197542514

Subjects: LCSH: Psychoses—Popular works.

Classification: LCC RC512 .C58 2021 (print) | LCC RC512 (ebook) | DDC 616.89—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020026338

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020026339 10.1093/med/9780190920685.001.0001

Foreword

Preface

Acknowledgments

PART I. ANSWERING SOME KEY QUESTIONS

What Is Psychosis?

What Are the Symptoms of Psychosis?

What Diagnoses Are Associated with Psychosis?

What Causes Primary Psychotic Disorders Like Schizophrenia?

PART II. CLARIFYING THE INITIAL EVALUATION AND TREATMENT OF PSYCHOSIS

Finding the Best Care: Specialty Programs for Early Psychosis

The Initial Evaluation of Psychosis

Medicines Used to Treat Psychosis

Psychosocial Treatments for Early Psychosis

Follow-Up and Sticking with Treatment

PART III. HELPING YOU LOOK AHEAD TO THE NEXT STEPS

Knowing Your Early Warning Signs and Preventing a Relapse

Staying Healthy Embracing Recovery

Going Back to School and Work

Reducing Stress, Coping, and Communicating Effectively: Tips for Family Members and Young People with Psychosis

Understanding Mental Health First Aid for Psychosis

Glossary Index

Foreword

The weeks and months during and following an initial episode of psychosis can be incredibly challenging, and also frightening, for young people, their families, and their broader social networks. During this period, access to reliable, up-to-date information is critical. This is exactly what this book provides: accurate and helpful information, resources, and support. The book educates readers about the symptoms of psychosis and how they are defined, the meaning of different diagnoses, and what the latest science tells us about underlying causes and effective treatments. Material covered includes the initial evaluation of psychosis, advances in the area of early intervention services, and information on evidence-based medications and psychosocial treatments. Importantly, chapters also provide practical advice on treatment engagement, relapse prevention, physical health and well-being, returning to school or work, and effective communication.

Since the first edition, much has changed in the treatment of firstepisode psychosis. Specialized early intervention programs are now available in virtually every U.S. state, and in many parts of the world. These programs are team-based, recovery-focused, infused with shared decision-making, and centered around the young person’s and family’s own goals. The worksheets in this book—and the entire book itself—are designed to increase young people’s and family members’ knowledge and confidence, in turn strengthening communication with mental health professionals.

A fundamental message of this book is that treatment is effective and recovery is possible. I say that with confidence in part because I have been there: experiencing early psychosis, benefiting from specialized early intervention services, and now living a rich, and in many ways very “normal,” life. Early in the course of psychosis it is of course easy to feel overwhelmed and hopeless; I encourage readers

to always remain hopeful. While the challenges are real, thousands of young people in recovery, pursuing their goals, attest to the fact that challenges can be overcome. What can easily seem like a dead end in hindsight turns out to have been just a bend in the road. On that road, this book and the recovery-oriented supports it describes are a powerful resource on the journey to recovery.

Internationally, thousands of studies on psychosis are published every year. In this book, Beth Broussard and Michael Compton have distilled this science to what young people and families most need to know Of course, mental health professionals will also share information tailored to individual situations, but the information contained in this book provides a comprehensive foundation regarding what we know about the causes, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of psychosis, and guidance on getting back on track. There are certainly still many things we don’t fully understand about psychosis, but the field has made many important advances in the past decade and continues to move forward. This updated second edition reflects what we know and helps support the recovery process.

Nev Jones, PhD, Assistant Professor, Morsani College of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA

Preface

While the questions that open Chapter 1—often asked by young people experiencing psychosis and their families—might be the same as those from more than a decade ago when the first edition of this book was published, the answers have evolved. Treatment is getting better. Hope is more pertinent than ever before. Recovery and a full life are now achieved by many more people facing a first episode of psychosis. In this second edition, we share the latest information that we think will help you most effectively deal with this difficult situation. We have again aimed to provide readers with a complete guide explaining everything you need to know during this critical time of initial evaluation and treatment.

We often use the terms first episode of psychosis, first-episode psychosis, and early psychosis. They refer to the initial period of experiencing symptoms and the mental health evaluation and treatment for this episode of psychosis. Some individuals will go on to experience further episodes of psychosis, in which case the use of the term first episode is truly warranted. However, we do not mean to suggest that everyone who has a first episode of psychosis will necessarily go on to have future episodes. For some people, the symptoms clear up with treatment and they achieve long-term remission and recovery without later episodes.

We want to provide you with the information that you need to begin a path toward recovery or to go about helping your loved one embrace recovery. We invite you to read this book and gather from it whatever information is helpful to you. The book is divided into three parts, each one building on the next as you learn more about the first episode of psychosis. Important terms are shown in bold and definitions for each of these words are included in the glossary at the end of the book. We also invite you to visit a straightforward companion website for additional resources, including printable

versions of the worksheets found in the book. Visit: www.oup.com/firstepisodepsychosis.

Hope and optimism for recovery are warranted, especially given the growing availability of specialty care. However, our optimism is balanced by a deep recognition of how serious the first episode of psychosis is. We strongly encourage young people and families to seek evaluation and treatment as soon as possible; to work together with experienced, specialized mental health professionals; and to stick with treatment. Through collaboration with experts in the treatment of psychosis, young people with psychosis and their families have the best chance to move beyond psychosis and toward recovery.

Beth Broussard, MPH, CHES, Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Atlanta, GA, USA

Michael T. Compton, MD, MPH, New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, Department of Psychiatry, New York, NY, USA

Acknowledgments

We are delighted to be able to publish a thoroughly updated second edition that highlights the many advances of the past decade in early intervention services. Like the writing of the original text, this update and expansion has required substantial work, and we have benefited from the support and assistance of many. We would like to thank a number of dear colleagues who generously volunteered to review draft chapters for us, including Stephanie Langlois at DeKalb Community Service Board (Atlanta, GA); Robert Cotes at Emory University (Atlanta, GA); Leah Pope and Jason Tan de Bibiana at the Vera Institute of Justice (New York, NY); Tehya Boswell and Adria Zern at Columbia University (New York, NY); Nicole Havas at Lenox Hill Hospital and Northwell Health (New York, NY); and Iruma Bello, Leslie Marino, Hong Ngo, and Ilana Nossel at OnTrackNY (New York, NY). We are very fortunate to have such generous, hardworking, dedicated, and compassionate colleagues.

We also remain very appreciative of our former colleagues in the ACES Project (Atlanta Cohort on the Early Course of Schizophrenia) who helped us draft the original versions of chapters for the first edition, as well as the numerous international experts who reviewed those chapters. Their names are not repeated here, but much of their work undoubtedly carries over to this updated second edition. We continue to admire their research, clinical programs, and commitment to young people with first-episode psychosis and their families.

We also thank the many people important in both our professional and personal lives who have tolerated the long hours spent on compiling the original book, and the additional hours preparing this second edition. Their support and kindness remain essential to our success. At Oxford University Press, we thank Sarah Harrington for

her ongoing encouragement, support, and assistance in guiding us through this project.

Finally, and most importantly, we acknowledge the young people who have experienced psychosis and their family members, who inspire us and continue to teach us that recovery is possible. We hope that our efforts will be helpful in their path toward recovery and embracing a meaningful, satisfying, and healthy life well lived.

B.B. and M.T.C.

PART I

ANSWERING SOME KEY QUESTIONS

What Is Psychosis?

What is happening? What are these voices? These odd and unusual ideas? What is causing it? What will the doctors do? Is this treatment necessary? Is this curable? Will it come back? How can our family cope? What should I do next?

These are some of the many questions that often go through the minds of young people experiencing psychosis and their family members. An episode of psychosis can be frightening. It can be confusing. It can even seem like life is changing forever. However, there is support for young people and their families. Know that treatment works, and recovery is possible. This book is meant to help readers through a very difficult time by providing much-needed information when taking the first steps toward recovery. Part I of this book, Answering Some Key Questions, explains some of the most important facts about psychosis. This chapter addresses the first question: What is psychosis?

In this chapter, we define what psychosis is and then dispel some myths by describing what psychosis is not. We then briefly describe what percentage of people develop psychosis and when it usually first begins. Next, we present the idea of a “psychosis continuum,” which means that experiences of psychosis can differ in their level of seriousness. We then set the stage for later chapters by briefly introducing several other topics to come in the book, including causes of psychosis, treatments, and recovery.

What Psychosis Is

So what exactly does psychosis mean? Psychosis is a word used to describe a person’s mental state when he or she has in some way

become disconnected from reality For example, a person might hear voices that are not really there (auditory hallucinations) or believe things that are not really true (delusions). It is a treatable mental illness that occurs due to a dysfunction in the brain. A mental illness affects a person’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. You may be familiar with some other mental illnesses, such as depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder. People with psychosis have difficulty separating false personal experiences from reality. They may have confusing speech patterns or behave in a bizarre or risky manner without realizing that they are doing anything unusual.

Similar to any other health condition, psychosis consists of a combination of different types of symptoms, which are described in detail in Chapter 2, “What Are the Symptoms of Psychosis?” Some of the many symptoms of psychosis may include hearing voices when there is really no one there, having unusual beliefs, feeling frightened or paranoid, being withdrawn, having confused thoughts or confusing speech patterns, or displaying odd behaviors.

A psychotic episode is a period of time during which someone has psychotic symptoms. These symptoms may make it difficult for the young person to carry out daily activities. A psychotic episode may last from days to weeks, or in some cases even months or years, depending on the person and whether treatment is received. In some cases, psychotic-like symptoms may last for only seconds or minutes but cause no problems or impairments, in which case they wouldn’t be considered a psychotic episode.

People who have a psychotic disorder have a mental illness that interferes with their life. The various psychotic disorders and other illnesses that may cause psychosis are described in detail in Chapter 3, “What Diagnoses Are Associated with Psychosis?” Some people with a psychotic disorder have repeating episodes but are able to function normally between these episodes. Others may have repeating episodes without a full recovery between them. Yet others may have only one episode in their lifetime.

An episode of psychosis can seriously disrupt one’s functioning. Both “positive symptoms,” such as hallucinations and delusions (called “positive” because these symptoms are abnormal experiences added on to normal experiences), and “negative

symptoms,” such as decreased energy and motivation (called “negative” symptoms because they have subtracted, or removed, something from the person’s experience), can interfere with school, work, and relationships. These and other types of symptoms are described in detail in Chapter 2.

Before a psychotic episode, family and friends may notice changes in emotions, behaviors, thinking, and beliefs about oneself and the world. They may see changes in mood, sleep habits, and participation in social activities. These changes, often called prodromal symptoms, are some of the early warning signs for a psychotic illness (see Chapters 2 and 10, “Knowing Your Early Warning Signs and Preventing a Relapse”).

The experience of psychosis is different for each person. For some people, substance use, self-harm, or confusion may start or get worse with an episode of psychosis. Others may feel more tension or distrust. Family and friends should know that any unexpected or aggressive behavior is likely a reaction to hallucinations and/or delusions, which are very real for the person with psychosis. It is important to realize that unusual thoughts or behaviors are part of a treatable illness. Family and friends should understand that their loved one often does not have control over these thoughts and behaviors. Although the symptoms of psychosis may be frightening to the individual and his or her family, there are good treatments for these symptoms. Friends and family members should help the individual to receive the right mental health treatment.

First-episode psychosis is the period of time when a person first begins to experience psychosis. This book focuses on the first episode of psychosis because it is during this time that young people and their families need detailed information about the initial evaluation and treatment. The first few years during and after a first episode of psychosis is a critical period. That is, the early phase of psychosis is very important because it is during this time that longterm outcomes may be most improved by treatment. This is also a critical period because crucial psychological and social skills are developing, and mental health professionals want to minimize the interference to these skills that psychosis can cause. It is vital that

individuals with psychosis and their families seek help in order to move toward recovery. The first episode of psychosis benefits most from specialized, thorough, and ongoing treatment that provides individuals with psychosis the best possible outcomes.

It is vital that individuals with psychosis and their families seek help in order to move toward recovery The first episode of psychosis benefits most from specialized, thorough, and ongoing treatment that provides individuals with psychosis the best possible outcomes

What Psychosis Is NOT

Before learning more about psychosis, it is important to address some common myths and misconceptions about psychosis.

Psychosis is not multiple personality disorder. In multiple personality disorder (a very rare psychiatric disorder that is now called dissociative identity disorder), a person unconsciously has two or more separate personalities. Each personality has its own thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Although people with psychosis may hear voices or behave in response to delusions, they do not alternate between different personalities. So, psychosis is not “split personality” or multiple personality disorder.

Psychosis is not insanity. The word insanity is a historical legal term that usually meant that one was too mentally ill to be held responsible for a crime (as in the phrase “not guilty by reason of insanity”). A very small percentage of individuals with psychosis and criminal charges fall into this legal classification. Usually, people with psychosis are not legally insane, nor do they usually commit crimes. Insanity is a word that is no longer used in the medical field. People with psychosis are not “crazy.” People with psychosis should not be called crazy; instead, they are suffering from a treatable mental illness. Mental health professionals view the word crazy as an outdated and damaging word, like insanity or lunacy. Nowadays, mental health professionals encourage others not to use the word crazy because it leads to stigma and discrimination. People with a mental illness can still have friends and meaningful relationships, as well as go to school and have jobs. So, even though it is a commonly used word in society, referring to someone as “crazy” is harmful.

Psychosis is not psychopathy. The word psychotic describes someone who is experiencing psychosis. Psychopathy is a personality disorder in which people lack empathy, have no regret for criminal or violent behaviors, and are socially manipulative. Although both mental illnesses contain the prefix psycho, they are completely different. Most people diagnosed with psychosis are not violent, and most people diagnosed with psychopathy (also called sociopathy or antisocial personality disorder) do not have hallucinations or delusions. So, psychosis does not equal psychopathy or criminal behavior.

Psychosis is not delirium. People with delirium, or a state of confusion, may have trouble with memory and concentration. They

may be disoriented, meaning that they do not know the date, where they are, or possibly even who they are (see Chapter 3). Although some people with psychosis have poor memory, they generally know who they are, where they are, and what the date is. So, psychosis is not the same as being delirious. Psychosis is also very different from dementia, which is a slowly developing state of confusion and memory loss that usually occurs in old age (see Chapter 3).

People with psychosis are not usually violent or a threat to others. In fact, they are at greater risk for injuring themselves than injuring others. Family and friends should understand that people with psychosis are rarely violent. They are suffering from an illness and need the same caring attention as people with any other health condition.

Psychosis and disability do not always go hand in hand. Recovery is possible. The experience of psychosis is different for every person who has it. Psychosis is more disabling for some people than for others because of individual differences in personality, social support, genes, and life experiences. The right treatment can help lessen or remove the distressing symptoms of the illness. Many people with psychosis can recover to participate in their communities.

Developing Psychosis

Psychosis affects both men and women across all cultures. When the symptoms of psychosis come together to form a syndrome that lasts for some time and causes impairment, it is often called a psychotic episode. That syndrome of psychosis, or the psychotic episode, can be classified into several different diagnoses, as described in Chapter 3, including psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia. Very few people (about 3%, or 3 in 100) will experience a psychotic episode in their lifetime. Although it can happen at any time in life, the onset or beginning of an episode of psychosis that is diagnosed as a psychotic disorder is usually in late adolescence or early adulthood. For men, the usual age of onset may be earlier than for women. That is, on average, men who

develop a psychotic disorder experience their first psychotic symptoms up to three to five years before women do. For example, the symptoms of schizophrenia usually first become apparent in men between the ages of about 20 and 30, and in women between the ages of about 24 and 34. Schizophrenia is one of the most serious psychotic disorders, and about 1% of people will develop schizophrenia during the course of their lifetime.

The Psychosis Continuum

Everyone has some tendency to have psychotic-like experiences or even psychosis, just as everyone has the potential to become depressed or anxious. Normal experiences that are similar to psychosis, though much milder, do not interfere with an individual’s regular functioning. Abnormal experiences of psychosis interfere with functioning and make it difficult for a person to live a regular life. The more an experience interferes with daily life, the more serious the condition.

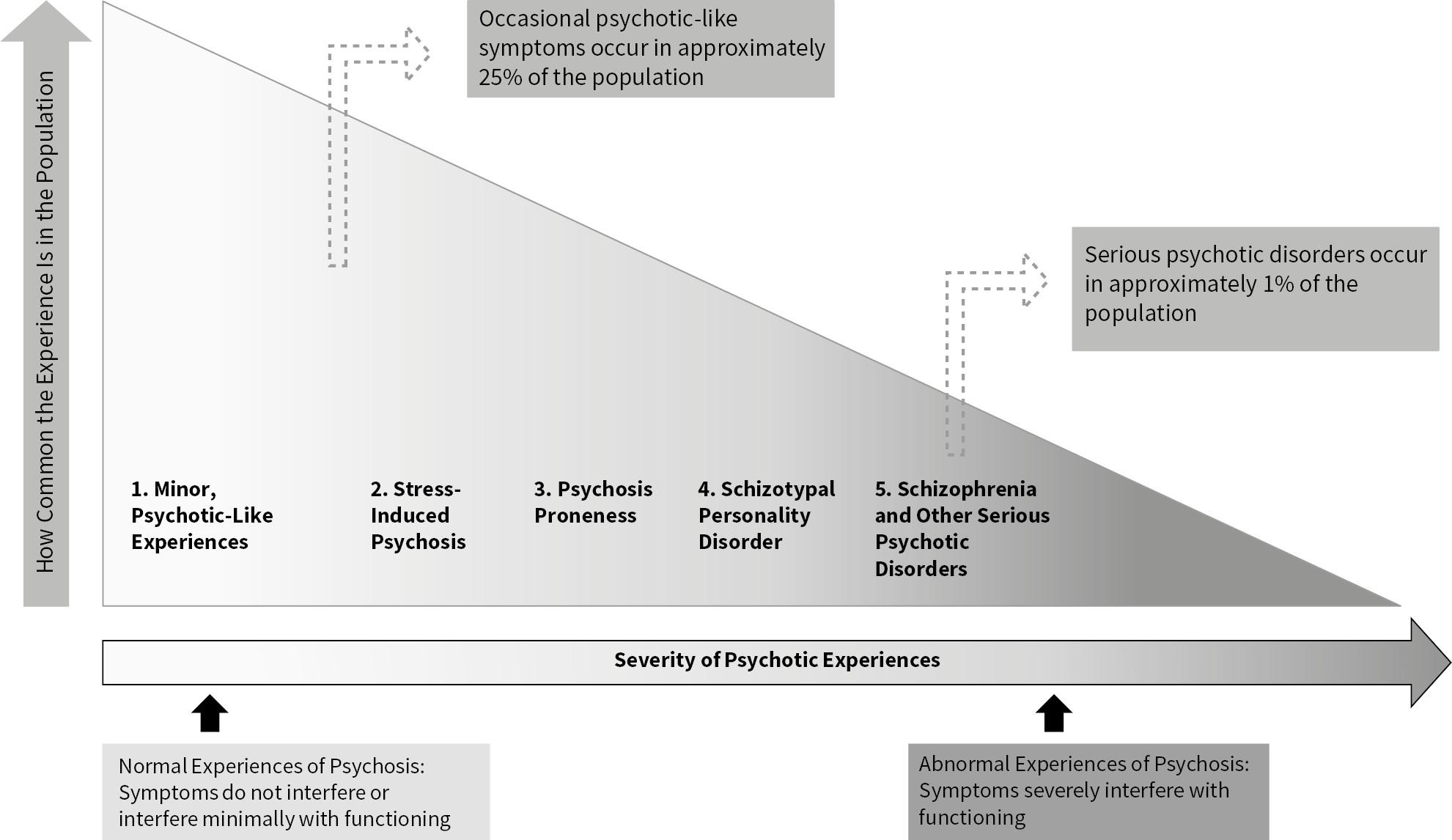

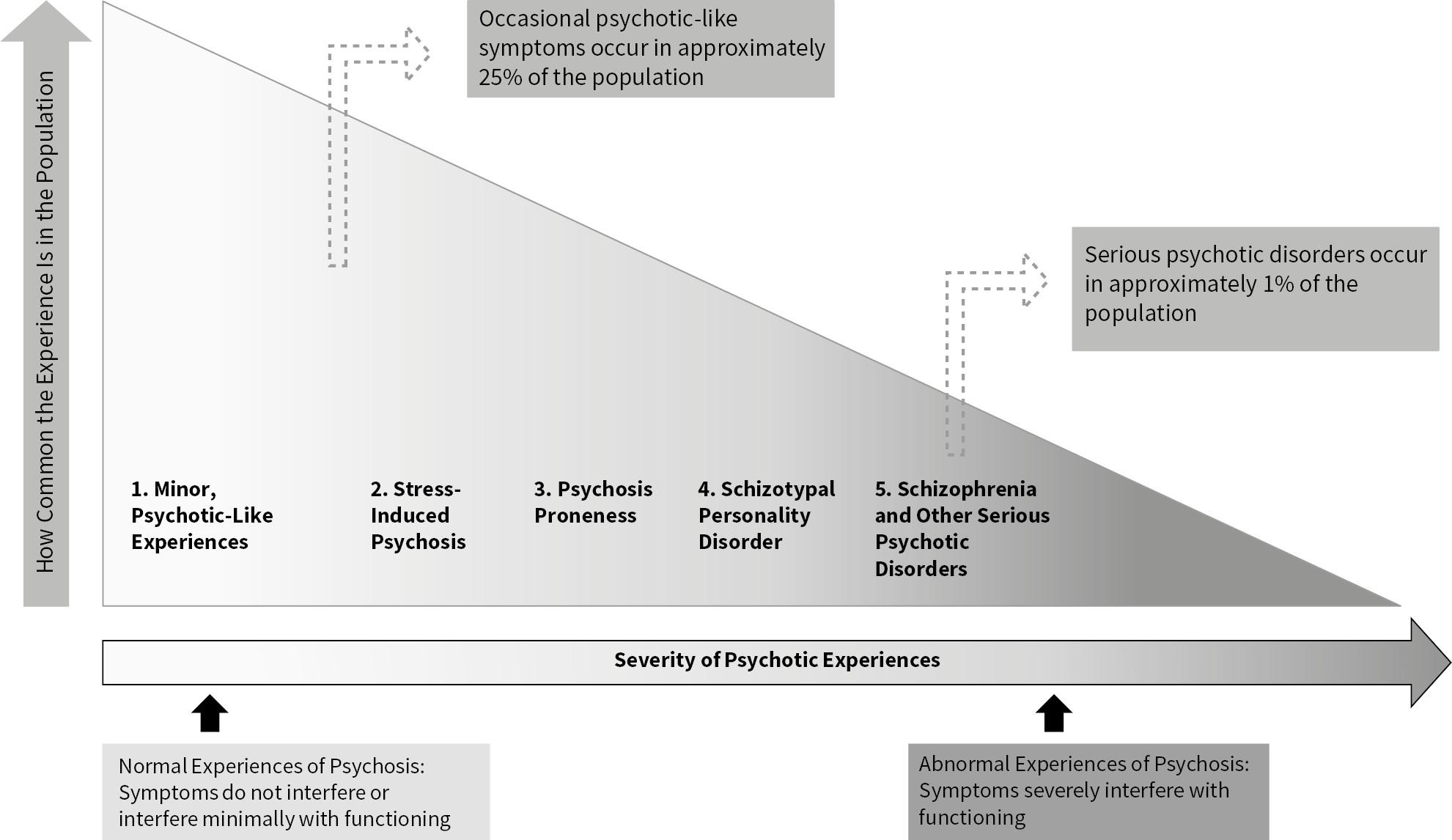

Researchers who study psychosis use the phrase psychosis continuum to describe the different levels of experiences. This means that there is a range of severity or seriousness across the different types of experiences of psychosis. The different types of experiences range from normal experiences that are similar to psychosis and that cause little or no distress, to the full syndrome of psychosis that causes much distress or many difficulties in life. Although normal psychotic-like experiences are fairly common, psychotic disorders that cause the full syndrome of psychosis are quite rare. Figure 1.1 illustrates how the different types of experiences of psychosis relate to one another. The following five paragraphs relate to the five parts of Figure 1.1.

First, some normal human experiences that do not affect regular functioning are similar to psychosis. They cause no distress and do not interfere with life. We have all had the occasional experience of wondering if someone might be talking about us (which is a normal curiosity) or thinking that we hear the phone ring while taking a shower (which is a normal experience of attention being drawn to

sounds that may be heard over noise). Some people occasionally may have minor psychotic-like symptoms, such as hearing a voice or suspecting that someone is following them. These brief, infrequent symptoms do not disrupt functioning. About one-fourth (25%, or 25 out of 100) of people in the general population will experience these types of symptoms at some point in their lifetime. These are brief experiences that usually go away, and not the full syndrome of psychosis. Psychosis is an exaggeration of these experiences—to the point that they become troubling and interfere with life—caused by a dysfunction in the brain.

Second, certain experiences can cause a psychotic episode, such as major stress, drug use, and even some medical problems. Some examples of psychosis caused by stressors include stress-induced psychosis, drug-induced psychosis, and psychosis related to a medical problem. People who experience a great deal of physical stress from lack of sleep, hunger, torture, or severe psychological stress, may experience stress-induced psychosis. Drug-induced psychosis may happen when a person is using drugs like cocaine, LSD, marijuana, methamphetamine, PCP, or synthetic cannabinoids. People with certain physical illnesses, such as meningitis, certain types of seizures, or a brain tumor, may experience psychosis related to a medical problem (see Chapter 3). In all of these cases, the symptoms of psychosis often, but not always, go away after removing the stressor, drug, or medical problem. Some people do not fully recover from an episode of psychosis if the stressor or cause of psychosis is too intense or lasts for too long, or if they are at genetic risk for a psychotic illness.

Figure 1.1 The Psychosis Continuum. Shown here is the range of severity among the different types of psychotic-like and full psychotic experiences. These experiences range from experiences that produce no or minimal levels of distress (left side) to those that cause a lot of distress (right side)

Third, some people are particularly at risk for psychosis due to their genes or due to exposure to factors that may have occurred in early life. Such factors may include having an infection as a fetus or baby, a difficult labor or delivery when being born, having had a head injury, trauma or adverse experiences in childhood, or drug use in adolescence (see Chapter 4, “What Causes Primary Psychotic Disorders Like Schizophrenia?”). It should be noted that having any one or more of these risk factors increases one’s risk only slightly. Some people are more likely to develop psychotic symptoms than others. That is, some people are more psychosis-prone than others. They may or may not develop psychosis, but have a tendency toward it.

Fourth, people who experience mild, ongoing difficulties from symptoms but usually still function well enough to work and maintain relationships may have schizotypal personality features. People with schizotypal personality features can seem to have fewer social

skills at times or may have suspicious or paranoid thinking. They also tend to withdraw from society. Typically, they do not experience full hallucinations or delusions. When many schizotypal personality features are present and long-lasting, a person might be diagnosed by mental health professionals as having schizotypal personality disorder (or just schizotypal disorder). Schizotypal personality disorder is a stable set of personality traits that appear as a milder form of the symptoms of schizophrenia.

Fifth, people who have a full syndrome of psychosis and are diagnosed with a psychotic disorder often have more difficulty with employment, living independently, and maintaining personal and professional relationships. They may be unable to work, attend school, or participate in some social activities. Some of the treatments described in Chapters 5, “Finding the Best Care,” and 8, “Psychosocial Treatments for Early Psychosis,” are designed specifically to help with these difficulties. Either hallucinations, delusions, or both may be present during a psychotic episode. In addition, people with psychosis may experience slow or confused thinking and speech, and their behavior may be odd or risky. People with this experience of psychosis may have schizophrenia or another “primary psychotic disorder.” On the other hand, they may have a different type of mental illness, such as depression with psychotic features or bipolar disorder (also called manic-depressive illness). We describe these different psychiatric illnesses that can cause psychosis in more detail in Chapter 3.

There are also cases when the cause and trajectory of a psychotic-like experience are not clear. For example, some people have reported abilities related to their spirituality or religion, such as seeing or hearing things that other people cannot. These experiences usually do not interfere with an individual’s functioning, and one’s specific religion or culture considers them to be normal or special experiences. This book focuses on the types of experiences of psychosis that are abnormal or distressing.

Schizophrenia and Other Primary Psychotic Disorders

When someone has a headache, he or she may not know what is causing the headache. Is the headache from stress? Does the person have a cold or the flu? Or is the headache related to something more serious, like high blood pressure, or even a brain tumor? If the headache worsens or does not go away, it is a good idea to visit the doctor for medical evaluation and treatment. In the same way, psychosis can happen in several different illnesses, mostly in mental illnesses. For example, people with severe depression, with bipolar disorder, or with schizophrenia can have an episode of psychosis. There are many different types of psychotic disorders, and they are diagnosed based on the types of symptoms and how long those symptoms last.

For example, schizophrenia is a type of psychotic disorder in which at least two of the following occur for at least one month, but often much longer: hallucinations, delusions, disorganized speech, disorganized behavior, or “negative symptoms” (these symptoms are described in Chapter 2). Young people, in the age range of about 16 to 30, with a first episode of psychosis may or may not go on to develop schizophrenia. Nevertheless, mental health professionals always recommend a thorough evaluation (see Chapter 6, “The Initial Evaluation of Psychosis”), treatment (see Chapters 7, “Medicines Used to Treat Psychosis,” and 8), and follow-up (see Chapter 9, “Follow-Up and Sticking with Treatment”).

Schizophrenia is only one type of psychotic disorder, as described in Chapter 3. Others include brief psychotic disorder, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and delusional disorder. These disorders differ from schizophrenia by the types of symptoms present and the length of time those symptoms last.

Psychotic disorders have a unique set of symptoms that make them different from other mental illnesses, placing them in their own class of disorders. All mental illnesses are defined by a specific group or set of symptoms. For example, people with obsessivecompulsive disorder do not have hallucinations, but people with psychosis often do. In other words, the symptoms of obsessivecompulsive disorder, depression, social anxiety disorder, autistic disorder, or a number of other mental illnesses differ from the symptoms of psychosis.