1 Introduction

OnOctober 24, 1933, the former Associated Press reporter Lorena Hickok, en route from Washington, D.C. to Minneapolis, Minnesota, stopped to send a letter to her new boss, Harry Hopkins. What she had to say, she wrote, “could not very well be said over the telephone,” so she had chosen “to add another letter to the stack.”1

Over the summer, her boss, Hopkins, had been appointed director of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA in the alphabet soup of New Deal acronyms). With unemployment near 25 percent and crop prices at historic lows, some 18 million Americans—or roughly one in six families—lived in dire poverty.2 Hopkins, as head of FERA, would oversee the distribution of hundreds of millions of dollars in federal relief funds to individual states, most of which had long since exhausted their own resources; the states would then distribute those funds to individuals and families in need.

In August, not long after taking charge of FERA, Hopkins had hired Hickok to travel the country and investigate what she came to call, somewhat cynically, “the relief show.”3 By this Hickok meant how well—or, as often as not, how poorly—local agencies, using those federal funds, met the needs of those who sought relief. More generally, Hopkins wanted Hickok to investigate the state of the union during its moment of crisis. “What I want you to do,” he told her, is to go out around the country and look this thing over. I don’t want statistics from you. I don’t want the social worker angle. I just want your own reaction, as an ordinary citizen.

Go talk with preachers and teachers, businessmen, workers, farmers. Go talk with the unemployed, those who are on relief and those who aren’t. And when you talk with them don’t ever forget that but for the grace of God you, I, any of our friends might be in their shoes. Tell me what you see and hear. All of it. Don’t ever pull your punches.4

The Emotional Life of the Great Depression . John Marsh, Oxford University Press (2019). © John Marsh. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198847731.001.0001

By the time she left for Minneapolis in October, Hickok had investigated an infamous slum in Washington, D.C., “the Alleys”; in late summer, she had made a trip through Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Kentucky, New York, and Maine. And in Minneapolis, she would begin a six-week journey through the plains states: Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa, and then back to Minnesota.

In the letter she sent en route to Minneapolis, Hickok wrote Hopkins that before she left Washington, Louis Howe, who had craftily managed Franklin Roosevelt’s political career for the last twenty years, had asked her “to do some special work for him while I was in the middlewest.” Howe was “interested in finding out what sort of treatment people are getting from government representatives who deal with them directly when they ask for help.” “He feels it is a matter of great importance,” Hickok added, “and I certainly agree with him.” Meanwhile, Henry Morgenthau, head of the Farm Credit Administration, another New Deal program, this one devoted to extending low-interest loans to farmers at risk of losing their mortgaged farmland to foreclosure, had “also asked me to pass on anything I might hear about the workings of his department out there.”5 Hickok, loyal to Hopkins, and conscious of who paid her salary, wanted to clear such requests with him.

Everyone in Washington, it seemed, wanted to see and hear what Hickok heard and saw while “in the middlewest.” One can rather easily guess why: because the Midwest was exploding.

In January 1933, Ed O’Neal, head of the usually politically placid American Farm Bureau Administration, had told Congress, “Unless something is done for the American farmer we will have revolution in the countryside in less than twelve months.”6 O’Neal may have exaggerated, but not by a lot. In August 1932, seeking prices for their crops that would keep them and their families alive, farmers in Sioux City, Iowa declared a farm strike, blocking the roads into town and turning back trucks carrying produce to market.7 At roughly the same time, Sioux City dairy farmers called their own strike, which quickly spread to nearby communities and states. When striking dairy farmers caught trucks trying to deliver milk to cities, however, they did not merely turn the trucks around. At a time when some people literally starved to death and millions more went hungry, strikers poured the milk out by the side of the road. It formed brilliant white pools in the ditches.8

In addition, that winter, as Ed O’Neal warned Congress of revolution in the countryside, farmers across the Midwest, but especially in Iowa, had

occasionally assembled to prevent banks from selling off the hundreds of thousands of mortgaged farms that had gone into foreclosure. At bank auctions, groups of farmers would gather by the hundreds, one would bid pennies for the property and everything on it, while the others would intimidate outsiders from bidding anything more. And just like that, an evicted farmer owned his farm again.9 In a similar vein, farmers would gather in courtrooms to intimidate judges who processed foreclosure claims. Occasionally, they did more than merely intimidate. In April 1933, after the new Roosevelt administration had taken office, farmers in Le Mars, Iowa kidnapped a judge from his bench after he refused to suspend foreclosure proceedings against mortgaged farms. The farmers drove the judge to the outskirts of town and went through the motions of lynching him from a telegraph pole.10

Then, in the fall of 1933, just before Hickok left for the Midwest, and with the clock counting down, farmers did everything they could to make good on the revolutionary prediction O’Neal had made. In September, Illinois dairy farmers voted to withhold milk from Chicago until they got the prices they wanted. “Farm War On” the Chicago Tribune declared.11 That same month, the National Farm Holiday Association, the closest thing farmers had to a union, declared a national strike.12 A few days earlier, the governor of North Dakota—the governor, mind you—joined farmers in that state in declaring a wheat embargo until prices rose. Unlike governors in other states, the governor of North Dakota threatened to call out the National Guard not to keep the roads open, thereby allowing farmers to deliver their crops to markets, but to patrol the roads, making sure that trucks and trains crossing the bridge over the Red River into Minnesota did not contain wheat. In strike parlance, the National Guard would be the picket.13 In October, dairy farmers in Wisconsin renewed their milk strike. In late October and early November, they started bombing creameries.14

Into this developing revolution drove Lorena Hickok in a used Chevrolet Cabriolet nicknamed “Bluette.”15 She would leave the Midwest impressed less by the militancy of farmers than by their incredible suffering. Three incidents from her first week in North Dakota suggest both how the Great Depression had begun to affect Americans and how the Great Depression had begun to affect those, like Hickok, whose job it was to document how it affected others.

After speaking with Minnesota governor Floyd Olson, Hickok left for Bismarck, North Dakota. From there she drove to Dickinson, North Dakota to a rural church that doubled as the county relief agency. “Grouped about

the entrance to the church,” she wrote Hopkins back in Washington, “were a dozen or more men in shabby denim, shivering in the biting wind that swept across the plain.” “Farmers, these,” she commented, “ ‘ hailed out’ last summer, their crops destroyed by two hail storms that came within three weeks of each other in June and July, now applying for relief.” Hickok sat in with the relief investigator who took down their stories. “Again and again on the application appeared the statement, ‘Hailed out. No crop at all.’ ” “Of the men I saw this afternoon,” she wrote, “none had any income.” “For themselves and their family they need everything,” Hickok observed. “Especially clothing.” Although only October, it was already bitterly cold in North Dakota. When Hickok returned to her car from the church, she “found it full of farmers, with all the windows closed. They apologized and said they had crawled in there to keep warm.”16

After Dickinson, Hickok drove to Minot, North Dakota, in the northern part of the state. At the relief office in Minot, she met “a quiet, mild-mannered, Scandinavian wheat farmer seeking a loan.” “He’d been ‘hailed out again,’ ” he said. His assets, Hickok listed, included thirty head of cattle, sixteen horses, some hogs, some farm machinery, a tractor—“which he hadn’t used for several years because he couldn’t afford to”—and 320 acres of land. His liabilities, meanwhile, had accumulated: “Bank of North Dakota, mortgage on a quarter section of his land, $800; farm implement company, $400; blacksmith, $300; hardware company, for spare parts, tools, etc. $1000; back taxes, $600; U.S. feed and seed loans, $500. A total of $3,600.” “During the conversation,” she wrote,

the secretary of the Farmers’ Loan Association, taking his application, asked: “How are you fixed for the winter in food and clothes for your family?”

The man didn’t answer. Instead, his eyes filled up with tears—which he wiped away with the back of his hand.

The question was not repeated. And for the second time since I’ve been on this job I found myself blinking to keep tears out of my own eyes.17

It must have taken a lot for Hickok, who spent years honing a persona of the hard-boiled reporter, to admit to having to blink back tears. (She never tells Hopkins of the first time she had to.) At least, as Hickok observes, the investigator had the decency not to repeat the question.

From Minot, Hickok drove to Bottineau, North Dakota, flush against the Canadian border. “I visited this afternoon,” she wrote her close friend, the first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, whom she had met while working as an Associated Press reporter, “one of the ‘better’ homes of people on the relief

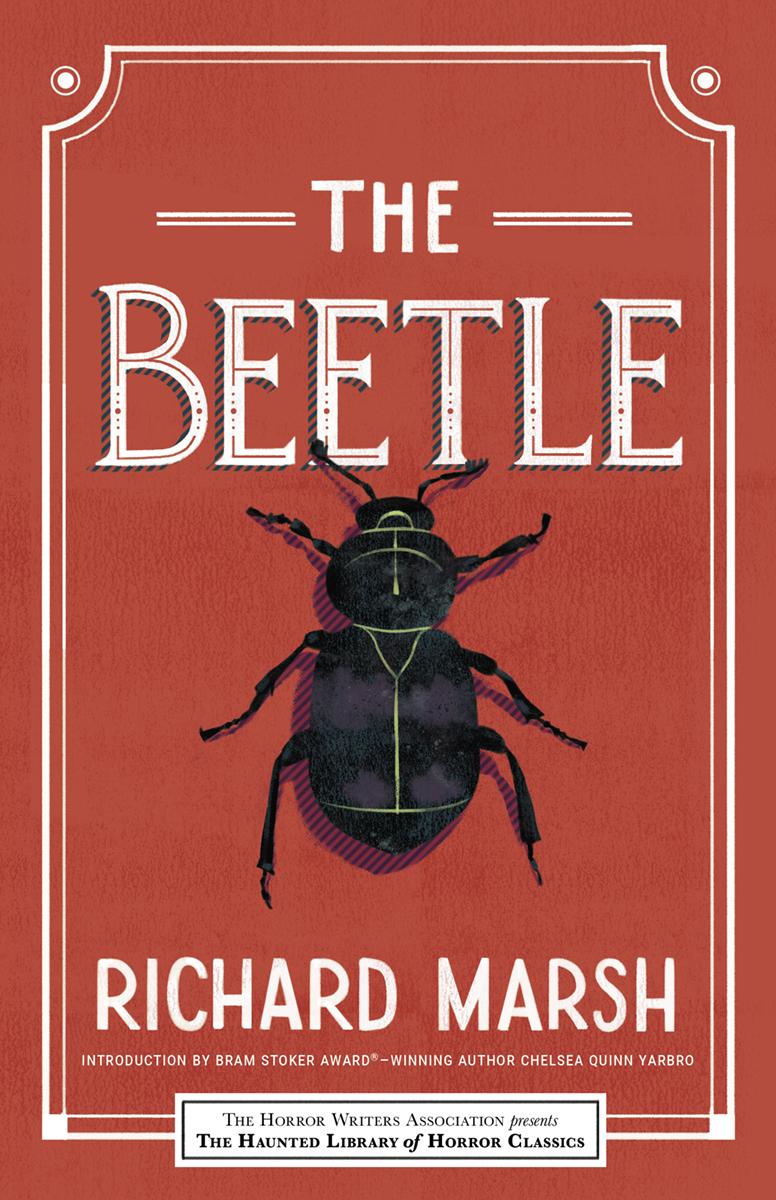

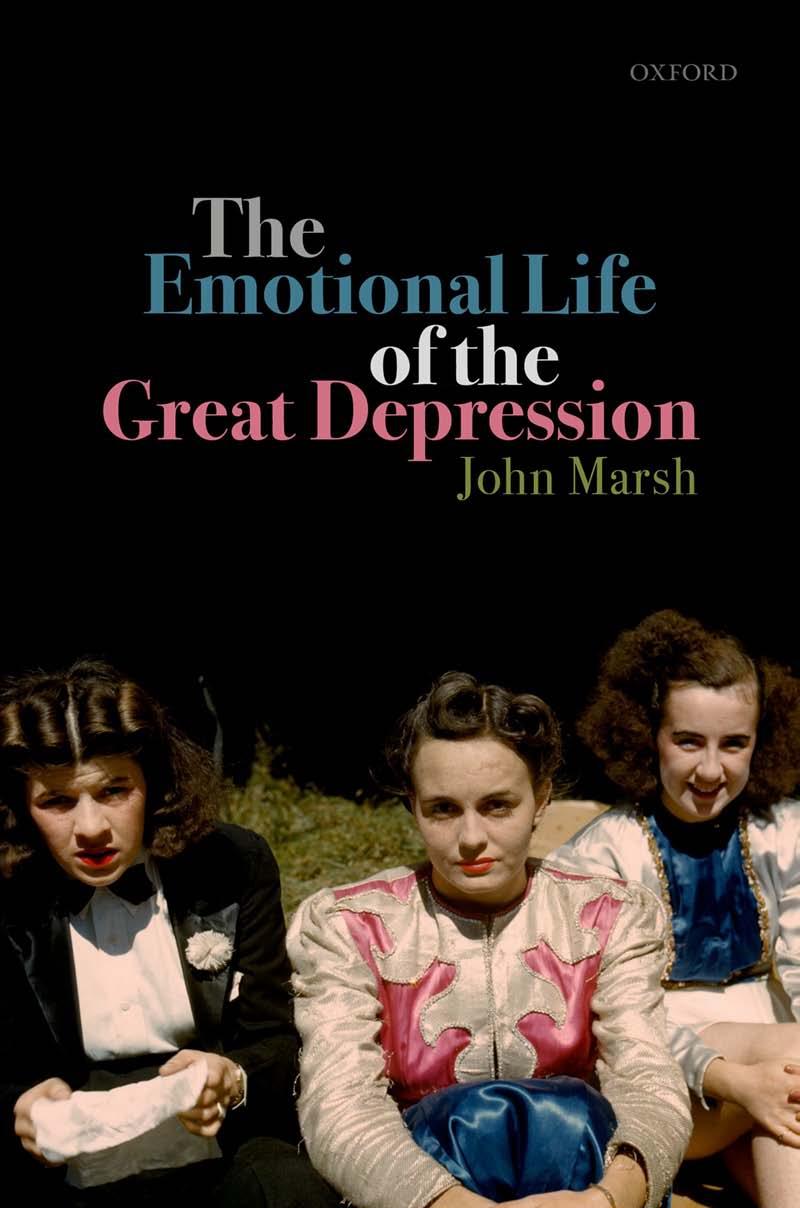

Source: Bettmann/Contributor/Getty

rolls” (see Figure 1.1). Hickok observed that no real repairs had been made to the house in years. The kitchen floor had been patched up with tin can lids and old automotive license plates; newspapers had been stuffed into cracks in the walls where plaster had fallen away; and daylight shone beneath a crack in the door. “And in that house,” Hickok wrote, having earlier observed that winter had already arrived, and that the previous winter the temperature had dropped to 40 degrees below zero and stayed there for ten days, “two small boys . . . were running about without a stitch on save some ragged overalls. No shoes or stockings. Their feet were purple with cold.” Hickok noted—with horror—that the mother was going to have another baby in January. “In that house!” she exclaimed. “This, dear lady,” Hickok informed the first lady, “is the stuff that farm strikes and agrarian revolutions are made of.”18

From Sioux City, Iowa, in late November, Hickok confessed to Hopkins, “sometimes I feel damned ashamed for drawing down the salary I get for—just going around and observing!”19 She need not have felt ashamed. Hopkins evidently felt her salary was money well spent. Over time, he did not rely on Hickok and her observations alone. Eventually, he hired sixteen field investigators—including a young Martha Gellhorn—to circulate about

Figure 1.1. Lorena Hickok (on the left) with Eleanor Roosevelt in 1935.

Images

the country and take the American temperature.20 He did so because, as Louis Howe and Henry Morgenthau also knew, how Americans felt about the Great Depression mattered intensely. How well did state and local relief agencies meet the needs of suffering Americans? Would Americans continue to suffer quietly? Or would they, like farmers in the Midwest, revolt? How did they feel about the president and the New Deal? Most importantly, when and from where would they summon the “animal spirits,” as the economist John Maynard Keynes would put it a few years later, that would lead the country out of its torpor and into recovery?

No one could answer those questions definitively, but more so than perhaps at any other point in American history, the future of the country seemed to depend upon the emotional life of ordinary Americans.

Contemporary psychologists somewhat faddishly speak of emotional intelligence: the “ability to monitor one’s own and other people’s emotions, to discriminate between different emotions and label them appropriately, and to use emotional information to guide thinking and behavior.”21 By that definition, Hickok had emotional intelligence to spare. Everywhere she went, in every report she wrote, she sought to discern how Americans felt, to label those feelings, and to speculate about what sort of actions those feelings would produce. “I have an idea that the chief trouble with the people in South Dakota,” she wrote Hopkins in November 1933, “the thing that is behind whatever unrest there is in the state, is sheer terror. Those people are afraid of the future. Some of them are almost hysterical.”22 She could also use emotions to guide thinking and behavior. After spending a week in North Dakota watching farmers freeze, Hickok lost her temper. “I wish I could find words adequately to express to you the immediate need for clothing in this area,” she wrote to Hopkins. “All I can say is that these people have GOT to have clothing—RIGHT AWAY.”23 The outburst worked. On the strength of its emotional urgency, and its appeal to human decency, the letter passed from Harry Hopkins to Louis Howe all the way to Franklin Roosevelt. On the copy of the report in the Roosevelt archives, a note appears indicating that the president himself called the head of state relief in North Dakota to see that farmers did indeed get clothing and other supplies at once—RIGHT AWAY.

Reading the reports that Hickok sent to Hopkins, however, and that Roosevelt administrators like Louis Howe and Henry Morgenthau vied to get their hands on, the term emotional intelligence acquires another meaning. Not intelligence in terms of individual ability or knowledge but intelligence

in terms of information. George Gallup would start his public opinion polling firm in 1935, but prior to that, basic information about how Americans felt either did not exist, came filtered through mediums like newspaper editorials or partisan journalism, or, like election results, arrived too infrequently to reveal very much at all. Hickok and other investigators filled that void in information. They were spies, if you like, though spies out to help those whom they spied on.24 Indeed, the reports that Hickok, Gellhorn, and others wrote for Hopkins offer some of the most insightful, moving writing about American life during the Great Depression in the then scant public record.

For all of their work, however, the emotional life of ordinary Americans during the Great Depression—and extraordinary ones, for that matter— remains something of a mystery. One knows that Americans suffered during the Great Depression, but what does that mean? Suffer how? Suffer what? Did they suffer equally? And what did they make of their suffering? Did they do anything besides suffer? Inspired by field investigators like Hickok, this book sets out to answer those questions.

The Conventional Wisdom

If answers to these questions do not come immediately to mind, thereby making a book like this one necessary, that may be because of the role the Great Depression has come to play in American history. If people have thought about the Great Depression lately, they have likely thought about it in the context of the Great Recession, when the latest economic catastrophe earned comparisons to the earlier one. In the wake of the Great Recession of 2008, that is, the Great Depression has often functioned less as history than as history lesson, and such an approach usually flies too far above the everyday life of the period to provide an intimate view of how ordinary people experienced it. In After the Music Stopped: The Financial Crisis, the Response, and the Work Ahead, for example, Alan S. Binder repeatedly refers to the Great Recession as the “Great Depression 2.0.”25 Indeed, in the midst and aftermath of that recession, economic historians returned to the Great Depression with newfound urgency. Liaquat Ahamed’s Lords of Finance and, especially, Barry Eichengreen’s Hall of Mirrors explored how an earlier generation of politicians and central bankers had, as Ahamed’s subtitle put it, “broke the world” and then struggled to put it back together again. Still

more urgently, these books asked if the latest generation of politicians and central bankers had learned anything from how their forebears had responded to the previous economic catastrophe. More to the point, they asked if they had learned the right lessons.

Scholarship rarely gets more relevant. Too often, however, in focusing on policy, on the decisions of elites and central bankers, these books tended to quantify rather than describe the experience of those who lived through the Great Depression. In the opening pages of Lords of Finance, for example, Ahamed, adopting a global perspective on the Great Depression, writes that by 1931,

production in almost every country had collapsed—in the two worst hit, the United States and Germany, it had fallen 40 percent . . . Ar mies of the unemployed now haunted the towns and cities of the industrial nations. In the United States, the world’s largest economy, some 8 million men and women, close to 15 percent of the labor force, were out of work Gangs of unemployed youth and men with nothing to do loitered aimlessly at street corners, in parks, in bars and cafes. As more and more people were thrown out of work and unable to afford a decent place to live, grim jerry-built shantytowns constructed of packing cases, scrap iron, grease drums, tarpaulins, and even of motor car bodies had sprung up in cities such as New York and Chicago— there was even an encampment in Central Park . . . In the United States, millions of vagrants, escaping the blight of inner-city poverty, had taken to the road in search of some kind—any kind—of work. Unemployment led to violence and revolt. In the United States, food riots broke out in Arkansas, Oklahoma, and across the central and southwestern states.26

Similarly, in Hall of Mirrors, Eichengreen recounts how “just as the US treasury allowed Lehman Brothers to fail in September 2008 in part to make a political statement and correct the moral hazard created by its earlier bailout of Bear Stearns,” in 1933 the Reconstruction Finance Corporation allowed Guardian Trust, a Michigan Bank, “to go under.” “This was a disaster of miscalculation and obduracy all around,” Eichengreen concludes, reciting the grim economic statistics then facing the nation. “By February of 1933 industrial production in the United States had fallen to just 53 percent of its 1929 level. Prices had collapsed. Unemployment was approaching 25 percent. The banking system was allowed to disintegrate over the misplaced priority attached to moral hazard.”27

Eichengreen is right, and Ahamed paints an accurately grim if nevertheless blurry picture. The problem, however, lies in the fact that while economic indicators like how much industrial production had fallen off,

whether prices had collapsed, what number unemployment approached, and how many millions of vagrants had taken to the roads mean a great deal to economists and policymakers, and indirectly to everyone who seeks to avoid recessions and depressions, they only vaguely represent the experience of people who lived out those economic indicators, who lost jobs, who could not feed their families for what their crops sold for, who watched their savings disappear in bank failures, or who—one by one and not by the millions—took to the roads. It sounds sloganeering to say it, but the economy does not matter, people do—or the economy matters because people do. Economists know that as well as others, but their reliance on numbers rather than stories can obscure that basic truth. “You can pity six men,” Harry Hopkins wrote in his 1937 memoir, Spending to Save, “but you can’t keep stirred up over six million.”28 As the Great Recession has come to frame histories of the Great Depression, however, readers have been asked to pity 6 million men rather than six. Ironically, in such accounts, that mythic figure of the Great Depression, the forgotten man, risks being forgotten yet again.

Earlier histories of the Great Depression, those that predate the Great Recession, do not suffer from this problem to nearly the same extent. In seeking to tell the story of “the ordeal of the American people,” as one of the most famous histories of the Great Depression puts it, many of them draw on the reports Hickok wrote for Hopkins and, whether consciously or not, strive to represent the emotional ordeal of the American people in the Great Depression as well.29 Yet while these works acknowledge the emotional lives of Americans, they suffer from their own limitations and contribute to keeping the emotional life of Americans in the shadows. As a rule, these works tend to focus on a handful of emotions, on what I have come to think of as the canon of Great Depression feelings. Like canonical books of the Bible, this canon includes only those sacred Great Depression emotions accepted as genuine. These canonical emotions comprise—and rarely stray far from—despair, fear, anger, and, following the election of Roosevelt in 1932, hope. Of these, though, fear and despair have become hyper-canonical, the ur-emotional texts of the Great Depression. Moreover, these emotions have come to define the literary canon qua canon of the period as well. Although, as I argue later in this book, it hits other emotional notes, the novel that has outlived and defined the decade of the 1930s better than any other, John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, survives in the cultural imagination—despite a title that promises anger—as a book principally

about despair. In sum, the conventional wisdom would have you believe that during the 1930s Americans felt despair and fear to the exclusion of all other emotions. That same conventional wisdom would also have you believe that sometimes they went to the movies, but only to escape their despair and fear.

Of course, the conventional wisdom is not wrong. If fear and, especially, despair dominate popular histories of the Great Depression, that is because those emotions largely did define the decade. In writing to Eleanor Roosevelt of the dust storm that overtook her outside Huron, South Dakota, Lorena Hickok speaks of her own brush with “desolation, discomfort, and misery,” as if those emotions, those synonyms for despair, wandered the landscape like figures out of the Bible.30 And so they did.

That said, although fear, despair, and other canonical emotions capture an essential, perhaps the defining part of life in the Great Depression, they leave out a lot, too. By the time Hickok made it to Sioux City, Iowa in late November, for example, she had found intimations of optimism. The farm strike had started in Sioux City and, Hickok reminded Hopkins, “it was a hotbed of ‘the reds’ ”—that is, communists. 31 But the arrival of the Civil Works Administration (CWA), a predecessor to the Works Progress Administration, both of which tried to put the unemployed and the needy to work, had pacified many of those inclined to rebel. Instead of surplus goods from the grocery store, which they had received on relief, CWA workers would earn wages, which they could spend how they pleased. “The CWA gangs, some 20 men,” Hickok wrote Hopkins,“were putting in shoulders along an old and rather narrow paved road. It was a nasty morning. Cold. And sleet. But they looked cheerful. Thirty-hour week, 40 cents an hour—CASH, instead of grocery orders.”32 In other Iowa towns—Des Moines, Ottumwa—the CWA seemed to have the same good effect. In early December, Hickok returned to Sioux City to report on the area two weeks after the CWA had arrived.“You get a feeling of optimism all through the area,” she wrote. “All the little towns have got out Christmas tree decorations. They’ve strung evergreens above Main Street.” “I hope I’m not unduly optimistic,” she added, “but it does look darned good.”33

Earlier in the month, Hickok had found an even more surprising emotion than optimism. In South Dakota, she met a woman “who has ten children and is about to have another.” She had so many children, Hickok observed, “that she didn’t call them by their names, but referred to them as ‘this little girl’ and ‘that little boy.’ ” Hickok added, “And despite the fact

that her husband was out of work and that they had no money and were terribly ragged, she seemed contented and happy enough. ‘This (White River) used to be quite a town,’ she said cheerfully, ‘but it’s kinda gone down hill lately.’ ”34

I do not think the Great Depression made many people content or happy, or if that is too high of a bar to clear, that many people had their contentedness or happiness left untouched by the Great Depression. But its presence on the plains of South Dakota serves as a warning not to rule anything out.

To put it plainly, the emotional life of the Great Depression ranged beyond the canonical emotions, beyond despair and fear, and to understand it, one must understand them, too. In sum, when the Great Depression appears only in the guise of macroeconomic lesson, or when it appears only in the costumes of its most familiar emotions, much of the decade remains lost to us.

So What?

Although the details of how Americans responded to the Great Depression may seem of interest to only a small group of historians and literary critics or those, like me, who cannot stop thinking about the decade, in fact they concern anyone who cares about contemporary life in the United States. Indeed, the Great Depression matters, and continues to matter, for a host of reasons.

It matters economically. Economists understand how capitalism works precisely because it failed so spectacularly during the Great Depression. It matters ethically. The Depression poses, in dramatic and sweeping terms, the question of what responsibility one has to relieve the suffering of another, and what role the state can play in discharging that responsibility. The stakes, quite simply, could not be higher. Those stakes perhaps explain why historians focus so intently on the widespread despair of the decade. Without despair, without suffering, the question of who owes what to whom would lose much of its urgency. In any case, rarely did Americans get so clear a chance as they did during the Great Depression to test the proposition that, as Michael Ignatieff famously put it, needs make rights.35 In revisiting the Depression, when so many needed so much, readers today retake that test.

And it matters politically. With apologies to Arthur Miller, the Great Depression is the American crucible: a test the country survived, but also a crisis in which events and responses to those events interacted to produce something new, to produce, really, the country Americans live in today. The Great Depression, Ahamed writes, “was the seminal economic event of the twentieth century.”36 In many ways, it was the seminal political event, too. Nearly every one of the political fights that make newspapers today—over taxation, the budget, the role of government, on and on—began or drew blood during the Great Depression. As a result, the 1930s represents a decade we can never understand fully enough, if, that is, we wish to understand ourselves and the origin of our own political divides. To study it is to study us.

Admittedly, these reasons for why the Great Depression matters can seem suspiciously high-minded; at times, they read like reasons why the Great Depression should matter rather than reasons why it really matters. For that, one must confess that the Great Depression might matter most of all because it offers a terrifying yet enthralling glimpse into the fragility of economic life. The journalist and literary critic Edmund Wilson called the Great Depression the American Earthquake.37 It is an apt metaphor. Like an earthquake, everyone felt the Great Depression. Like an earthquake, it caught everyone off guard. And like an earthquake, it devastated lives and landscapes. (Like an earthquake, it also had aftershocks.) And if you are at all like me, you cannot help but wonder how people, in the midst of that chaos, responded emotionally to the destruction that followed. How did it feel to lose a job, lose a home, to not have enough to eat? How did it feel to not suffer those fates yet know that they could visit you at any moment? And how did it feel to live among so many undone by economic disaster?

The Great Depression matters because it provides a horrible but natural experiment for answering such questions, in part because those who lived through it left behind so many documents—from diaries to gangster films to the great American novel—attesting to how they felt about what happened to them. In his 1931 poem “Papermill,” to take but one example, Joseph Kalar writes of a factory once alive with sound and motion but that now, after the Depression, lies in a “clammy silence.” Kalar composes the poem almost exclusively in the present tense, as though time, like the factory, has also stopped. The whole scene is, as the refrain of the poem puts it, “Not to be believed.” In the closing lines of the poem, Kalar turns to the workers of the mill, who offer their own variation on the refrain:

Where once feet stamped over the oily floor, Dinnerpails clattered, voices rose and fell In laughter, curses, and songs. Now the guts Of this mill have ceased their rumbling, now The fires are banked and red changes to black, Steam is cold water, silence is rust, and quiet Spells hunger. Look at these men, now, Standing before the iron gates, mumbling, “Who could believe it? Who could believe it?”38

In reading “Papermill,” one feels pity for the tragedy that befalls the workers and, if Aristotle is right about tragedy, fear that there but for the grace of God go I. (I may not work at a paper mill, but my job could suddenly disappear one day, too.) But, in keeping with the Aristotelian theme, what one may feel above all is catharsis, which does not mean the purification or purgation of emotion but the “clearing up” or “clarification” of something, in this case, the perception and apprehension of an emotion.39 Yes, one thinks, it would be unbelievable for a once thriving mill to close and take with it a whole way of life. Or, if, like many of the men and women I grew up around in northeastern Ohio in the 1970s and 1980s, you yourself stood outside the gates of a closed factory, you would think, if you had not before, that yes, when the mill closed, at first it was simply unbelievable.

The Great Depression matters, then, and perhaps matters most of all, because it represents economic catastrophe, and one understandably wonders what it feels like to live through economic catastrophe. In reading of the Great Depression and, especially, in reading the literature of the Great Depression, you are like an athlete training for a race that others have run before you but that, with any luck, you will never have to run yourself, or never run again.

All of which raises the question of whether economic catastrophe on the scale of the Great Depression could happen a second time. Are we right to wonder what it would feel like to live through a Great Depression? Or, if it is never wrong to wonder, is our fear justified?

Yes and no. The discrete events that caused the Great Depression in the United States—a stock market crash, a banking crisis, and, to a lesser extent, accompanying recessions in European nations that dried up markets for American goods—could happen again and, to some extent, have happened again. Between October 2007 and February 2009, the S&P 500 lost over half its value. That could not match the Great Crash of 1929, in which the

S&P 500 lost almost all its value.40 Yet without the safeguards put in place to prevent a second Great Depression, the most recent stock market crash, like the earlier one, might simply have kept crashing. Much the same might be said for a banking crisis. During the Great Recession, hundreds of banks closed. During the Great Depression, thousands did. As I discuss in Chapter 3, a provision of the 1933 Banking Act, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which insures individual bank deposits, likely kept the number of bank failures in the hundreds instead of the thousands. It no doubt saved Americans from a familiar Great Depression scene: depositors lining up to withdraw their savings from banks while they still could. Moreover, what economists call automatic stabilizers, things like unemployment insurance—another piece of 1930s legislation—and food stamps, which increase as the economy recesses, cushion the blow of economic shocks. Without them, again, the Great Recession might have turned into a Great Depression. Even with them, we felt—to invoke an earthquake metaphor— the ground shake.

On the other hand, as Ahamed and Eichengreen both argue, for the most part central bankers and politicians have learned their lessons from the Great Depression, especially when it comes to monetary policy and the need for the federal government to spend in order to get private businesses spending again.41 Furthermore, economies no longer strain under the golden fetters of the gold standard, which constrained policymakers in the 1930s as they sought to combat the Depression.42

A theme emerges here. As the Great Recession demonstrates, the crises that caused the Great Depression did not disappear with it. They appear to go hand in hand with capitalism. The stock market will crash again; banks will make bad bets; and economies will fall into recession. But policymakers have gotten better at dealing with such crises. To continue the earthquake metaphor, the nation has constructed economic buildings that bend.

Or so one hopes. No matter how important the lesson, countries rarely learn anything by heart. Twenty-five senators and 171 congressional representatives voted against the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008. Some of them wanted a better bill; some of them wanted no bill at all. Those who wanted no bill at all did not see why taxpayer money should go toward bailing out sinking Wall Street banks, even if the sinking banks threatened to take the rest of the economy down with them.43 Righteousness, as I argue in Chapter 2, is a powerful emotion. Just as the Reconstruction Finance Corporation let the Guardian Trust bank fail in 1933 to avoid

creating moral hazards, some legislators would gladly cut the nation’s nose off to spite its face.

Be that as it may, we do not need a Great Depression—or a Great Recession—to experience economic catastrophe. In any given month, recession or no, well over 1 million people lose their jobs.44 With the number of foreclosures lower than ever, some 60,000 homeowners still file for foreclosure every month.45 True, a Great Depression or Great Recession magnifies suffering. It makes it that much more difficult, for example, to find a job. (At the start of the Great Recession, on average two people applied for every job opening; by the end, six people did. If the unemployment rate correlates with the job-seekers rate, during the Great Depression the ratio of those seeking jobs to job openings must have risen well into the teens.)46 If economic catastrophe visits enough people, it gets called a recession or depression. But just because economic catastrophe does not rise to a critical mass does not make it any less catastrophic for those whom it does visit. And even if it does not visit you, the prospect that it might creeps up on you in quiet moments. That makes the earthquake metaphor still more fitting. During the Great Depression and, to a lesser extent, during the Great Recession, the earthquake struck. It does not need to strike, though, for one to register its presence. Every time businesses fail, or the stock market dips, the ground rumbles, and you remember that fault lines run beneath you, too.

Methodology

In The Beauty of a Social Problem, Walter Benn Michaels has recently—and provocatively—argued that our feelings about a social problem like unemployment are “beside the point because how we feel about the unemployed has no connection at all to anything we might do about unemployment.” Michaels goes so far as to argue that a focus on the plight of the victims of unemployment may distract us from the inexorable function of unemployment. Regardless of how we feel about the unemployed, that is,“there would still be (our economy would still need) unemployment.”47 “Capitalism likes it,” he writes, “whether we do or not.” The social problem, he continues, “cannot be addressed by having better” attitudes toward it.48 In other words, Michaels argues, forget how you or others feel about capitalism or its victims. It makes no difference. Focus instead on the injustices of capitalism.