https://ebookmass.com/product/the-caucasus-anintroduction-2nd-edition-thomas-de-waal/

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

The Oxford Handbook of Charles S. Peirce (Oxford Handbooks) Cornelis De Waal

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-oxford-handbook-of-charles-s-peirceoxford-handbooks-cornelis-de-waal/

ebookmass.com

We the people : an introduction to American government

Thirteenth Edition Thomas E. Patterson

https://ebookmass.com/product/we-the-people-an-introduction-toamerican-government-thirteenth-edition-thomas-e-patterson/

ebookmass.com

Critical Psychology: An Introduction 2nd Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/critical-psychology-an-introduction-2ndedition-ebook-pdf/

ebookmass.com

Microsoft Power Platform Fundamentals. Exam Ref PL-900, Second Edition Craig Zacker

https://ebookmass.com/product/microsoft-power-platform-fundamentalsexam-ref-pl-900-second-edition-craig-zacker/

ebookmass.com

His to Take (The Rowdy Johnson Brothers Book 1) Tory Baker

https://ebookmass.com/product/his-to-take-the-rowdy-johnson-brothersbook-1-tory-baker/

ebookmass.com

Ammonia volatilization mitigation in crop farming: A review of fertilizer amendment technologies and mechanisms Tianling Li

https://ebookmass.com/product/ammonia-volatilization-mitigation-incrop-farming-a-review-of-fertilizer-amendment-technologies-andmechanisms-tianling-li/ ebookmass.com

La revolución rusa Christopher Hill

https://ebookmass.com/product/la-revolucion-rusa-christopher-hill/

ebookmass.com

Endocrinology of Aging 1st Edition Emiliano Corpas

https://ebookmass.com/product/endocrinology-of-aging-1st-editionemiliano-corpas/

ebookmass.com

A Brief Response on the Controversies over Shangdi, Tianshen and Linghun Thierry Meynard

https://ebookmass.com/product/a-brief-response-on-the-controversiesover-shangdi-tianshen-and-linghun-thierry-meynard/

ebookmass.com

Systems Mapping, How to build and use causal models of systems Pete

https://ebookmass.com/product/systems-mapping-how-to-build-and-usecausal-models-of-systems-pete-barbrook-johnson/

ebookmass.com

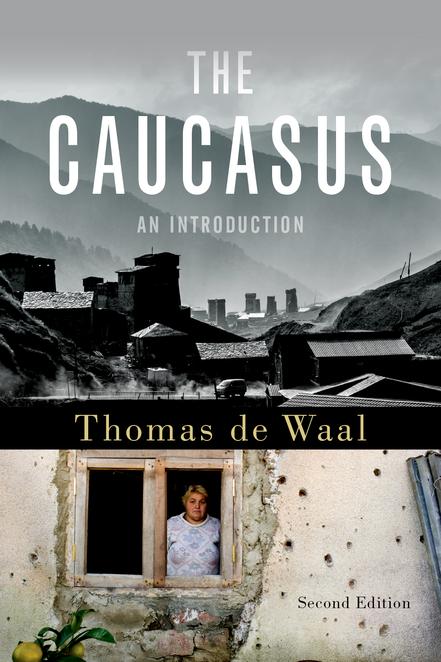

THE CAUCASUS AN INTRODUCTION

Thomas de Waal

1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: De Waal, Thomas, author.

Title: The Caucasus : an introduction / Thomas de Waal. Description: Second edition. | New York : Oxford University Press, 2018. Identifiers: LCCN 2018042733 | ISBN 9780190683092 (paperback) | ISBN 9780190683085 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Caucasus—Politics and government. | Caucasus—History. | Caucasus—Relations—Russia. | Russia—Relations—Caucasus. | Caucasus—Relations—Soviet Union. | Soviet Union—Relations—Caucasus. | BISAC: POLITICAL SCIENCE / History & Theory. | POLITICAL SCIENCE / Public Policy / Regional Planning. Classification: LCC DK509 .D33 2018 | DDC 947.5—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018042733

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Paperback printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America Hardback printed by Bridgeport National Bindery, Inc., United States of America

Author’s Note

Such is the complexity of the South Caucasus that this small book has taken more time than it should. For generous supply of comments, expertise, corrections, and support I offer heartfelt thanks to Margarita Akhvlediani, Laurence Broers, Sopho Bukia, Jonathan Cohen, Magdalena Frichova, George Hewitt, Seda Muradian, Donald Rayfield, Laurent Ruseckas, Shahin Rzayev, Larisa Sotieva, Ronald Suny, and Maka Tsnobiladze; for photographs and more to Halid Askerov, Leli Blagonravova, (the late) Zaal Kikodze, Gia Kraveishvili, (the late) Ruben Mangasarian, and Vladimir Valishvili; for elegant and informative maps to Chris Robinson; for making the book possible to my agent David Miller and editors Dave McBride and Alexandra Dauler; for putting up with the book in their midst to my dearest wife and daughter Georgina Wilson and Zoe de Waal.

A brief word about definitions and language. I tread carefully here but will inevitably end up offending some people. I use the word “Caucasian” literally to describe people from the Caucasus region. The old-fashioned usage of the word, still encountered in the United States, to denote whiteskinned people of European descent is the legacy of a discredited racial theory devised by the eighteenth-century German anthropologist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach. The Caucasus is a region where different nationalities have called places by different names at different times. I take a pragmatic approach of calling places by the name that was most accepted at a certain historical moment. So I write “Tiflis” for Georgia’s main city until the early twentieth century, when it was called by its Georgian version, “Tbilisi”; and I write “Shusha” and “Stepanakert” for the two main towns of Nagorny Karabakh. For the region as a whole, I use the term “Transcaucasus” when talking about it in a Russian historical context but otherwise stick to the more neutral “South Caucasus.” Sometimes I will risk offending people from the North Caucasus—which is outside the scope of this book—by writing “Caucasus” when I mean only the area south of the mountains. The North Caucasus is a separate world, equally fascinating and complex, far more within Russia’s sphere of influence. The South Caucasus is complex and demanding enough for a small book.

THE CAUCASUS

Introduction

The countries of the South Caucasus have always been the “lands inbetween.” In between the Black and Caspian seas, Europe and Asia, Russia and the Middle East, Christianity and Islam, and, more recently, democracy and dictatorship. Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia and the territories around them have the mixed blessing of being at the crossing-place of different cultures and political systems. These fault lines have made their region a geopolitical seismic zone. The kind of local shock that might be muffled elsewhere in the world reverberates more loudly here. That was what happened in August 2008, in the tiny territory of South Ossetia, a place with barely 50,000 inhabitants: an exchange of fire between villages escalated into a war between Georgia and Russia and then into a grave crisis in relations between Moscow and the West.

The war over South Ossetia was an extreme illustration of the principle that “all politics is local.” The people on the ground were at fault only inasmuch as they called for help from their big outside patrons. A chain of response went from Georgian villagers to the Georgian government in Tbilisi to Georgia’s friends in the West; the Ossetian villagers called for help on their own government, which looked to its protector in Moscow.

For such a small region—it has a population of just fifteen million people and the area of a large American state—the South Caucasus has attracted a lot of Western interest since the end of the Soviet Union in 1991. A series of political agendas coincide here. There is a desire to resolve the three

The Caucasus in 2010

ethnoterritorial disputes over Abkhazia, Nagorny Karabakh, and South Ossetia and calm a potential area of instability—the crisis in South Ossetia was in fact the smallest of the three conflicts. There is continued commercial and political interest in the energy resources of the Caspian Sea, which may contain 5 percent of the world’s oil and is likely to have a role to play in Europe’s future gas supplies. There is support by the large Armenian diaspora in the United States, France, and other countries for the newly independent Republic of Armenia. There has been political investment in Georgia’s ambitions to be a model of post-Soviet reform. There is also the challenge of the South Caucasus as an arena of engagement and, more often, confrontation with Russia.

The United States in particular has discovered the South Caucasus. Over the last decade, a number of very senior figures in Washington have taken an interest in the region. In May 2005, President George W. Bush stood in Freedom Square in the Georgian capital, Tbilisi, and told Georgians, “Your courage is inspiring democratic reformers and sending a message across the world—freedom will be a future of each nation and every people on earth.” A year later, Senator John McCain was presented with a Georgian sword on his seventieth birthday and told Georgians, “You are America’s best friends.” Azerbaijan, the largest and wealthiest of the three countries of the region, drew a steady stream of high-level political and commercial visitors from the United States. In the U.S. Congress, a powerful Armenian lobby ensured that Armenia was for a while the largest per capita recipient of U.S. aid money of any country in the world—aid to Georgia would soon match that level. The danger of these kinds of interventions is that they are too narrow and focus on one part of the picture and not the whole. Yet the whole picture is deeply complex and makes the Balkans seem simple by comparison. In the past its multiple local politics have defeated the strategists of the Great Powers of the day. In 1918 British general Lionel Dunsterville tried to sum up the situation he was supposed to be sorting out:

There are so many situations here, that it is difficult to give a full appreciation of each. There is the local situation, the all-Persia situation, the Jangali situation, the PersianRussian situation, the Turkish-advance-on-Tabriz situation, the question of liquidating Russian debts, the Baku situation, the South Caucasus situation, the North Caucasus situation, the Bolshevik situation and the Russian situation

as a whole. And each of these subdivides into smaller and acuter situations for there is no real Caucasian or even North or South Caucasian point of view, there is no unity of thought or action, nothing but mutual jealousy and mistrust. Thus the Georgians of Tiflis regard the problem from a Georgian point of view and play only for their own hand; the Armenians and the Tartars in the south, and the Terek and Kuban Cossacks and the Daghestanis in the north, do the same.1

In a place as complicated as this, a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing. In this conjunction of the deeply local and the global, the small players can overestimate their importance, and the big players can promise too much. The history of the Caucasus is littered with mistakes based on these kinds of assumptions and miscalculations. In August 2008, Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili blundered into a war over South Ossetia, almost certainly believing he had more support in the West than he actually did. The biggest problem in the South Caucasus, the unresolved ArmenianAzerbaijani Nagorny Karabakh conflict, is an earlier example of how a dispute about local grievances has caused international havoc. When it began, it was a local dispute in a far-off Soviet province, but it proved to be the first link in a long chain that eventually tugged down the whole structure of the Soviet Union. Nowadays, the dispute literally divides the South Caucasus in two and, by virtue of its proximity to oil and gas pipelines, has a bearing on European energy security.

For the West, ill-judged intervention can be dangerous for another reason: the South Caucasus—or Transcaucasus—was for long periods part of the Russian Empire or the Soviet Union and remains a zone of intense Russian interest. Russian strategists often regard Western interest in the Caucasus as dilettantism. Although no one believes that the West will abandon the Caucasus to Russian interests as the Western powers abandoned it to the Bolsheviks in 1920, there is more than a grain of truth in this. Modern Russia has a more sustained strategic interest in this region on its borders than any Western powers are ever likely to have. To take one example, in 1993 it was Russia, not the West, that agreed to set up a peacekeeping force for the conflict zone of Abkhazia, in which 120 Russian soldiers subsequently died. Western countries were not interested in a peacekeeping mission for this remote and unstable area. That decision set the stage

for Russia’s subsequent outmaneuvering of the West in Abkhazia many years later. Yet Russia also overestimates its understanding of the Caucasus and confuses agreement with subservience in a place like Abkhazia. Power in the Caucasus is generally in inverse proportion to knowledge: the small peoples of the region, speaking multiple languages and keeping a keen eye open, understand their more powerful Great Power neighbors much better than vice versa.

Thus, there is a big gap in understanding about the South Caucasus, which this book hopes partly to fill. It is part portrait and part history, with an emphasis on the events of the last twenty-five years, since the three nationstates of the region achieved independence from the wreckage of the Soviet Union. My aim is to focus firmly on the local dynamics of the region while putting them within a broader context. To get a proper perspective on this region, you need both zoom and wide-angle lenses.

The South Caucasus is in many ways a constructed region. Some will say that it exists only in the mind, in the memory of a Soviet- era generation, and in the vision of policy analysts who devise concepts such as the “Eastern Partnership” project. Actually, the cynics say, the South Caucasus “region” is just a tangle of roadblocks and closed borders that has no common identity beyond a shared past that is being rapidly forgotten. I make no apology for opposing that view. I believe that the South Caucasus does make sense as a region, and that the future of its peoples will be better served by them thinking as one. As I will make clear, there are strong ties of culture between the different nations of the Caucasus and patterns of economic collaboration that persist, even despite closed borders. A common history of Russian rule has shaped everything from railway systems to schooling to table customs. It is also worth considering the South Caucasus as a region in a negative sense, because its different interconnected parts have the capacity to do real harm to one another. Surrounded by bigger neighbors and entangled with each other’s problems, the countries of Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan and their breakaway territories cannot escape their Caucasian predicament even if they wanted to.

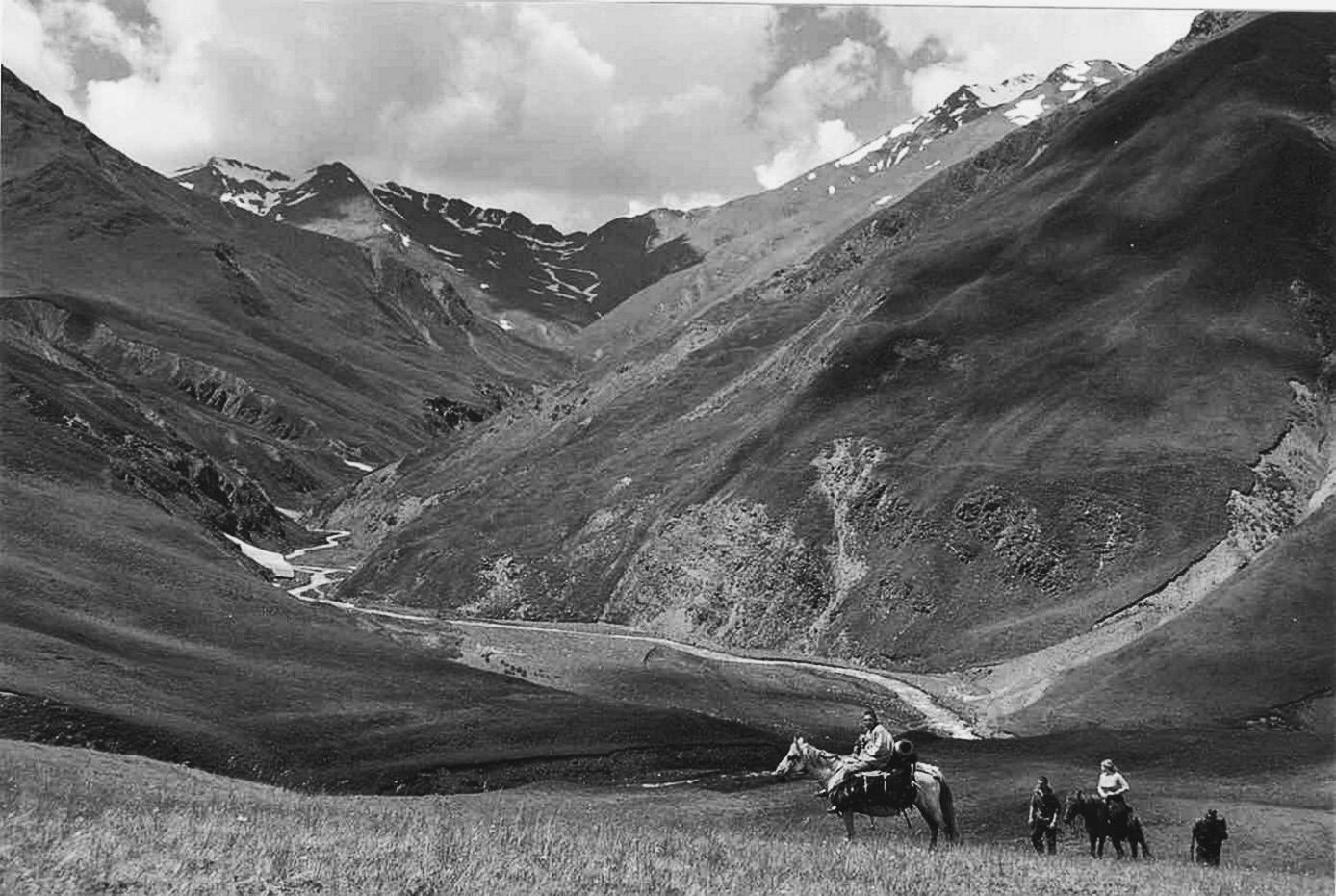

Among the Mountains

Boundaries

First of all there are the mountains. The Greater Caucasus chain is the highest mountain range in Europe—so long as you accept that the region is within Europe. Marking a barrier with the Russian plains to the north, they curve in a magnificent arc for 800 miles from the Black Sea to the Caspian Sea. Among the crowning peaks are the two extinct volcanic cones of Mount Elbrus (18,510 feet, or 5,642 meters) on the Russian side of the mountains and Mount Kazbek (16,558 feet, or 5,033 meters) in the north of Georgia.

For centuries, the name “Caucasus” was synonymous in Europe with wild cold mountains and with the myth of Prometheus, who stole fire from the gods and was punished by being chained to the icy peaks. In two references to the mountains, Shakespeare asked, “Who can hold fire in his hand / By thinking on the frosty Caucasus?” and wrote of a lover as “And faster bound to Aaron’s charming eyes / Than is Prometheus tied to Caucasus.” But two centuries later, Shelley had only a very vague idea of where the mountains actually were and set his verse drama Prometheus Unbound in “A Ravine of Icy Rocks in the Indian Caucasus.” It was only in 1874 that a team of English mountaineers climbed the higher peak of Mount Elbrus.

Thus, these mountains are both a colossal landmark and a powerful barrier, and the South Caucasus, the subject of this book, is defined as the region south of this barrier. In Russian, the region is known as the Transcaucasus, or Zakavkaz’ye, because in Russian eyes it is on the far side of the mountains.

The more politically neutral term “South Caucasus” has only gained usage since the three countries of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia achieved independence in 1991. Mountains define the southern parts of the region as well. A second chain, the Lesser Caucasus, runs to the south of the main range, giving Armenia and western Azerbaijan a mountainous landscape. These mountains turn south through the highlands that have come to be known as Nagorny—Mountainous—Karabakh. To the southwest of the Republic of Armenia loom the two peaks of the sacred Mount Ararat, which is inside the borders of Asian Turkey but dominates the horizon of the Armenian capital Yerevan on a clear day.

Not all of the South Caucasus is mountainous. It also contains the fertile wine-making plains of eastern Georgia, subtropical coastline on the Black Sea coast, and arid desert in central Azerbaijan. But highland geography is the prime cause of several special features of the region. The first is ethnic diversity: a mixture of nationalities lives within a relatively compact area with a population of only about fifteen million people. The Arabs called the Caucasus djabal al-alsun, or the “mountain of languages,” for its abundances of languages, and the North and South Caucasus together have the greatest density of distinct languages anywhere on earth. The South

Highland landscape in Tusheti, Georgia. Thomas de Waal.

Caucasus contains around ten main nationalities. Alongside the three main ethnic groups—the Azerbaijanis, Georgians, and Armenians—are Ossetians, Abkhaz, both Muslim and Yezidi Kurds, Talysh, and Lezgins. Most of them speak mutually unintelligible languages.

The main nationalities also contain linguistic diversity within themselves. If history had taken a different turn, some provinces might have ended up as their own nation-states. Mingrelians and Svans in Georgia speak their own languages, related to but distinct from Georgian. Karabakh Armenians speak a dialect that is hard to understand in Yerevan. North and South Ossetians speak markedly different dialects of Ossetian and are divided by the mountains. With ethnic diversity come strong traditions of particularism and local autonomy. Abkhazia, Ajaria, South Ossetia, Karabakh, and Nakhichevan were given an autonomous status under the Soviet Union that reflected older traditions of self-rule.

We inevitably end up calling the South Caucasus a “region,” but in many ways it isn’t one. Centrifugal forces are strong. The South Caucasus— or Transcaucasus—was first put together as a Russian colonial region in the early nineteenth century. The only historical attempt to make a single state, the Transcaucasian Federation, collapsed into three parts after just a month in May 1918. That breakdown created for the first time three entities called Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, which were then preserved under Soviet rule.

Three of the borders of this region are defined by geography, but the others less so. The first border, the Greater Caucasus chain, was established as a natural boundary thousands of years ago. The Greek geographer Strabo, writing in the first century ad, said it “overhangs both the Euxine and the Caspian Seas forming a kind of rampart to the isthmus which separates one sea from another.”1 The North Caucasus region on the other side of the mountains is mostly a separate world, sitting on the southern fringe of the Russian Federation with few links to the outside world. The North Caucasus is a mosaic of mainly Muslim nationalities inhabiting seven autonomous regions. The largest of them, Dagestan, was so important it was sometimes referred to as the “Eastern Caucasus.” The Russian Empire only fully conquered these territories in the 1850s and 1860s, a full fifty years after the takeover of Georgia. Three small ethnic groups have a foot in both the North and South Caucasus and make a narrow bridge between the two regions. In the west, the Abkhaz on the Black Sea coast have been part of Georgia for long periods of their history

but also have strong ethnic ties with the Circassian nationalities in the North Caucasus. In the middle of the region, Ossetians live on both the Russian and Georgian sides of the mountains, in both North and South Ossetia. In the east, on the Caspian Sea coast, the Lezgins are divided between Russia and Azerbaijan.

The other two natural boundaries of the South Caucasus, the Black and Caspian seas, have opened up the region to trade and invasion from both Europe and Asia. For centuries, the South Caucasus was located on the major east-west trade routes between Europe and Asia, forming a kind of lesser “Silk Road” passing through the ancient cities of Baku, Derbent, and Tiflis. The only historical exception to this was in Soviet times, when international borders were closed, this route was shut down, and all trade went north.

The fourth boundary to the south is mostly set by the river Araxes, or Aras, which was fixed as the border between the Russian and Persian empires in 1828. The Araxes runs for 660 miles from eastern Turkey between Armenia and Azerbaijan on one side and Iran on the other, until it meets the other main river of the region, the Kura, and flows into the Caspian Sea. Modern Azerbaijan extends south of the Araxes at its eastern stretch, encompassing the mountainous region where the Talysh people live.

Finally, the southwestern border south of the Black Sea, between Turkey on the one hand and Georgia and Armenia on the other, is the one defined most by history and least by natural geography. This area is called both Eastern Anatolia and Western Armenia, which gives some idea of its changing status over the centuries. In 1913, what is now the Turkish city of Kars was a Russian frontier town—a Russian travel guide of that year recommends that visitors take a look at its new granite war memorial. In the years 1915–21, this borderland was the scene of horrific bloodshed, as most of its Armenian population was killed, along with members of many other communities, and Turkish, Russian, and Armenian armies fought over it. The border was eventually drawn between Turkey and the new Bolshevik republics of Armenia and Georgia under the Treaty of Kars in 1921. The treaty established that the port of Batumi would be part of Georgia and conclusively gave Eastern Anatolia, including the Armenians’ holy mountain, Mount Ararat, to the new Turkish state. It thereby set the western frontier of the South Caucasus, which was further cemented by Soviet and Turkish border guards and the Cold War.

Belonging

Is the South Caucasus in Europe or Asia? By one definition, proposed by the eighteenth-century German-Swedish geographer Philip Johan von Strahlenberg, the region is in Asia, and the border with Europe runs along the Kuma-Manych Depression, north of the Greater Caucasus range. Other geographers, a bit more tidily, have made the mountains of the Caucasus themselves the border between Europe and Asia. Nowadays, the consensus is to place Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan in Europe and make the Turkish border and the river Araxes the Europe-Asia frontier. The strange result of this is that “Europe” in Armenia and Azerbaijan is directly due east of the “Asian” Turkish towns of Kars and Trabzon.

No definition is satisfactory because the South Caucasus has multiple identities. It is both European and Asian, with strong Middle Eastern influences as well. Politically the three countries, and Georgia in particular, look more towards Europe. They are members of the two European institutions, the Council of Europe and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE)—but then so is Turkey. The Georgian politician Zurab Zhvania famously told the Council of Europe in 1999, “I am Georgian and therefore I am European.” But Armenians maintain links with their diaspora communities in Iran, Lebanon, and Syria, and Azerbaijanis have affinities with the Turkic nations of Central Asia. In the end, it comes down to a matter of self-identification. At the beginning of Kurban Said’s classic 1937 novel of the Caucasus, Ali and Nino, set in Baku before and during the First World War, a Russian teacher informs his pupils that the Russian Empire has resolved the ancient geographical dispute over the Caucasus in favor of Europe. The teacher says, “It can therefore be said, my children, that it is partly your responsibility as to whether our town should belong to progressive Europe or to reactionary Asia”—at which point Mehmed Haidar, sitting in the back row, raises his hand and says, “Please, sir, we would rather stay in Asia.”2

The Caucasus also has its own identity. Anthropologists identify its customs and traditions fairly easily, and they get more marked the closer to the mountains one gets. The Caucasian nationalities share similar wedding and funeral ceremonies, and all mark the fortieth day after the death of a loved one with strikingly similar rituals. The same elaborate rituals of hospitality and toasting are found across the region, even among Muslim Azerbaijanis. Foreign mediators between “warring” Armenians and Azerbaijanis or

Georgians and Abkhaz have frequently seen how once the two sides sit down to dinner together, political differences are forgotten and convivial rituals of eating and drinking precisely observed.

Wine

The Caucasus may be the home of wine. Archaeological finds in southern Georgia, northwestern Azerbaijan, and northern Armenia suggest that Stone Age people took advantage of a temperate climate and the availability of wild fruit species to experiment with cultivating grapes.

In the 1960s, archaeologists in northwestern Azerbaijan found what seemed to be domesticated grape pips in their excavations dating from around 6000 bc. More recently, the American scholar Patrick McGovern found traces of wine in huge narrow-necked, five-liter ceramic vessels from this period excavated from the citadel of Shulaveri in Georgia. The wine had been treated with resin as a preservative. Around 2000 bc, craftsmen of the Trialeti culture in the same area were carving scenes of banquets on gold and silver goblets. And a millennium after that, the Greek historian Herodotus wrote that Armenian boatmen brought wine down the Tigris River to Babylon.1

Ceramic wine jars buried in the ground have survived through the centuries under different names. In 1829, Alexander Pushkin wrote, “Kakhetian and Karabakhi are worth several Burgundies. They keep the wine in maranis, huge jars, buried in the ground. These are opened with great ceremony. Recently a Russian dragoon secretly unearthed one of these jars, fell inside and drowned in Kakhetian wine, like the unfortunate Clarence in the butt of malmsey.”2

All three South Caucasian countries make and drink both wine and cognac. Azerbaijan’s vineyards were ravaged by Mikhail Gorbachev’s antialcohol campaign, and the revival of Islam has restrained drinking habits since

then. Armenia is most famous for its cognac. Brands such as Nairi and Dvin are admired all over the world—although the story that Winston Churchill liked to drink Dvin seems to be a legend disseminated by a popular Soviet spy television serial.3

Georgia is utterly inseparable from wine. It has more than 400 indigenous varieties, of which forty or so are commercial brands. The most popular brands are semisweet reds like Kindzamarauli and Khvanchkara and drier whites such as Tsinandali. The drinking of wine at the table is central to the nation’s collective identity. Caucasian banqueting and toasts attain an extra level of intensity in Georgia. A proper Georgian supra (banquet) lasts for many hours. A man is designated tamada (toastmaster) to lead the toasts and direct and entertain the other guests. The German anthropologist Florian Muehlfried argues that the rituals of the table became a way for Georgians to assert their difference from others and in particular vodkadrinking Russians:

“Since the Russians, unlike former invaders, shared the same religion as the Georgians, religion was no longer a distinguishing factor between ‘us’ (the Georgians) and ‘them’

Farmers in Kakheti, Georgia, bringing in the harvest. Vladimir Valishvili.

(the Russians). The ‘self-othering’ of the Georgian nation had to be based on something else: folk culture. The supra soon became a symbol of that cultural otherness, a manifestation of ‘Georgian’ hospitality based on a distinct way of eating, drinking and feasting.”4

Russia’s ban on Georgian wine was lifted in 2013. Disastrous in the short term, the embargo had an overwhelmingly positive long-term effect on Georgian winemaking. Production volumes dropped sharply, but quality improved radically. A series of new high-end wineries opened, many using the technique of making wine in a large ceramic jar known as a qvevri. In 2016, Russia was again the major export destination of what was now a much more diversified and higher-quality industry.5

1. Patrick E. McGovern, Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2003).

2. Alexander Pushkin, Journey to Erzerum.

3. See Irina Petrosian and David Underwood, Armenian Food: Fact, Fiction and Folklore (Bloomington, Ind.: Yerkir, 2006), 160–61. If the story has any basis in reality, it may be—although this is best not repeated in Yerevan—that Stalin introduced Churchill to Eniseli Georgian cognac when they first met in Moscow in August 1942 and Churchill flew a consignment home. See Cheryl Heckler, An Accidental Journalist: The Adventures of Edmund Stevens , 1934–1945 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2007), 205.

4. Florian Muehlfried, “Sharing the Same Blood—Culture and Cuisine in the Republic of Georgia,” Anthropology of Food (December 2007), http://aof.revues.org/index2342.html.

5. “Official: 50 Million Bottles of Wine Exported to 53 Countries in 2015,” Hvino News, January 4, 2017.

Ethnic and religious differences have always existed but are much more accentuated by modern politics. A century ago, attitudes toward religion could be deeply pragmatic. In her memoir of early twentieth-century Abkhazia, Adile Abas-oglu writes, “Arriving in Mokva for the Muslim festivals I always laughed when I observed how people drink wine and vodka at them and some families cooked holiday dishes from pork.”3 The émigré historian Aytek Namitok wrote: