Introduction

‘ReligionfromRome,PoliticsfromHome’?

‘Onelearned,quiteliterallyatone’smother’sknee,thatChristdiedfor thehumanraceandPatrickPearsefortheIrishsectionofit.’¹

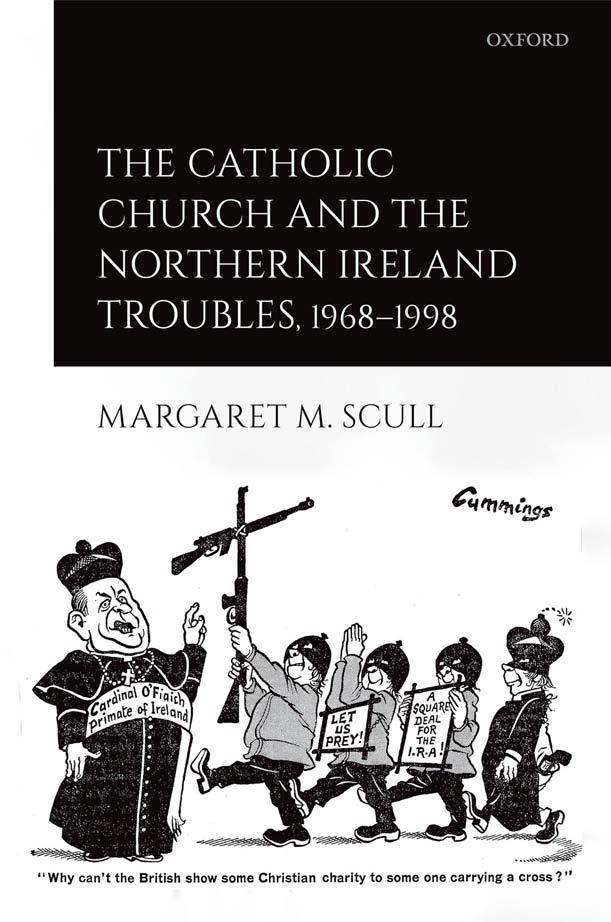

TomFeewasbornin1923inCullyhanna.²Hespenthisformativeyearsin Camlough,Co.Armagh,wherehisschoolmasterfatherraisedhimandhis brother,asasingleparent,afterhismotherpassedaway.Thefamilyowneda car,ararityinthecommunity,andtheboysexcelledinschool.Fromayoungage, Feeknewhewantedtojointheprestigiouspriesthoodandsetoffforthenational RomanCatholicseminaryforIrelandatStPatrick’sCollege,Maynooth.³Afterhis ordinationin1948,andabriefstintasanassistantpriest,Feebecameayoung facultymemberatMaynoothwherehetaughtonmanyaspectsofclericaltraining duringthe1950s,specializinginmodernhistory.ButFeewasdestinedtotakea differentpathfromthosewhoprecededhim.AstheconflictinNorthernIreland flared,dominatingtheIrishandBritishsocial,political,andreligiouslandscape fordecadestofollow,Fee’snationalistviewstookhold.Thesepoliticsledhimto adopttheGaelicversionofhisnameand,bythetimehebecamePresidentof Maynoothin1974,hewasknownasTomásÓFiaich(seeAppendix).Forareligious leadertoholdsuchviews,andregularlyvocalizehiswantforaunitedIreland, provedcontroversial.Theblatantlysectarian,outrageouspoliticalcartoononthe coverofthisbook,discussedingreaterdetailinChapter3,wasonesuchoutcome. Underhistutelage,andtheinfluenceoftheSecondVaticanCouncil,Maynooth brokewithtradition,rejectingteachinginLatininfavourofcoursesmainlytaught inEnglishandIrish.⁴ Radicalnewcourseson ‘theroleofpriestinsociety ’ were addedtotheseminarycurriculum,reflectinganewvisionforthepriesthoodand anupdatedecclesiology.⁵ However,thesechangeswerenottheresultofoneman’ s

¹EamonnMcCann, WarandanIrishTown (London,1993),65.

²Chaptertitlereference:K.TheodoreHoppen, Irelandsince1800:Conflict&Conformity (London, 1989),160–5.

³TheRomanCatholicChurchwillhenceforthbereferredtoastheCatholicChurchthroughout.

⁴ TomInglisarguesthatbeforeVaticanII,documentswerewritteninLatintodeliberatelyhide Churchbusinessfromthelaity;TomInglis, MoralMonopoly:TheRiseandFalloftheCatholicChurch inModernIreland (Dublin,1987),45.

⁵ Kalendarium:CollegiiStiPatritii,(Dublin,1975–76),51.

actions:thenationalseminaryforIrelandwasadaptingtochangingtimes,when thecountry’spriestswereneedednotonlyforritesoftheChurchbutalsotoactas leadersinsocialjusticemovements,representingfamilies,communities,and ideas.ÓFiaichwouldleaveMaynoothtobecometheArchbishopofArmagh andlaterjointheCollegeofCardinals,havingspenttwenty-fiveyearsdeveloping hisideasintheseminary.ÓFiaich’sjourneyreflectsawidertruth,explored throughoutthisstudy,aboutthepowerofindividualswithintheinstitutional CatholicChurchandtheirroleduringthecon flictinNorthernIreland.TomFee’ s evolutiontoTomásÓFiaich,withhisentrenchednationalistsympathies,wasnot anisolatedoccurrence.Similaritiescanbefoundinthestoriesofmanyother Church figureswhowereeitherthrustintothewiderpublicgazethrough theiractions,orwhoseizedtheinitiativetoforwardtheirinterpretationof whattheirworkshouldbeinaperiodofconflict,struggle,violence,andupheaval, thusdefininganewerafortheChurchanditsroleinNorthernIreland.

MaynoothwastheepicentreofIrishCatholictheologicalthought.Asigni ficant numberofpriestswhopassedthroughitshallsandbegantheirclericaljourneysin Co.Kildarewouldgoontoplaymajorrolesinpeaceandreconciliationinitiatives duringtheTroubles,theeuphemisticnamefortheconflictinNorthernIreland. Thelistofseminarystudentsandthoserecentlyordainedinthecollege’sannual Kalendarium constitutesacatalogueofindividualswhowouldgoontoworkas prisonchaplains,communityorganizers,parishpriests,andschoolteachers:all positionsofsocialinfluence.MostoftheIrishCatholicbishopsservedonthe BoardofDirectorsandmanypriestsactedaslecturersontheirwaytobecoming bishops.⁶ Maynoothpriestshada ‘homegrown’ feel:aspecialknowledgeofIrish history,thankstotheircurriculumwhichincludedthesubjectextensively;anda respectforIrishCatholicismdeeplyrootedinIrishnationalism.Priests’ time atMaynoothshapedtheirpastoralandtheologicalviewpoints,whichbecame apparentintheirworkinNorthernIrelandduringtheconflict.Theevolutionof theseminarybetweenthe1940sandthe1970sreflectedachangingpriesthood, andonethatreactedtotheconflictdifferentlyovertime.⁷

Maynooth,whileundoubtedlytheprimaryinfluenceontheclergy,wasnotthe onlysourceofnewideas.Returningmissionarieswerealsokeytothisevolutionin religiousthought.Thesein fluencesweremostkeenlyfeltwithintheclergywho didnotstudyatMaynooth.The fiveotherseminariesinIrelandwereexposed toexternalideasthroughthelargenumberofmissionaries.⁸ Allofpriestsinterviewedaspartofthisstudyrecountedhavingacousin,friend,orneighbourwho

⁶ ThehierarchywillrefertoCatholicChurchbishops,archbishops,andcardinalsinNorthern Ireland.

⁷ AnthonyAkinwale, ‘TheDecreeonPriestlyFormation, OptatamTotius’ inMatthewLamband MatthewLevering(eds.), VaticanII:RenewalwithTradition (Oxford,2008),237–9.

⁸ TheclergywillrefertodiocesanandreligiouspriestsinNorthernIrelandunlessotherwise specified.

camebackfromtheirmissiontrips filledwithdifferentperspectivesontheworld. Liberationtheology,ate rmcoinedin1971bythePeruvianpriestGustavo Gutiérrez,founditswaytoIreland throughmissionaryworkandglobal media.ItisaninterpretationofChristiantheologywhichemphasizesaconcern fortheexperienceofthepoorandoppressed.Liberationtheologydividedthe Church,withconservativebishopsfearingita ‘Trojanhorse ’ forCommunism.⁹ OnlyahandfulofIrishpriestsandwomenreligiousprofessedadherenceto thisnewtheologicalperspectiveandotherEuropeantheologicalin fluencessuch astheworker-priestmovement,whichspreadthroughoutFranceandItaly duringthe1940sand1950s,advocatingforaleft-leaningclergylivingalongside theirparishioners.¹ ⁰ However,asMarianneElliotthasnoted,theIrishCatholic Churchleftlittleroomforinnovationamongitspriests.Forexample,theBishop ofDownandConnorrefusedtosendpriestsabroad,fearingforeignin fl uences.¹¹ IntheNorth,asMauriceHayeshasargued,priestsweredrawnfromclosed communitiesandeducated ‘ inasortofenclosedclericalhothouse ’ beforereturningtotheircommunitieswithgreateroverarchingstatus.¹²Clericalattitudesona nationallevelinNorthernIrelandthroughouttheperiodofthecon flictwere constant,despitethein fl uenceofMaynoothforgradualreform.Nevertheless, therewerechangesonadiocese-by-diocesebasis,aswillbeexploredthroughout thisstudy.

Thisstudycriticallyanalysesthein fluenceoftheCatholicChurchinmediating betweenparamilitaryorganizationsandtheBritishgovernmentduringtheNorthernIrelandTroublesfrom1968to1998.ItcontendsthattheroleoftheChurch, especiallyinitsattemptstoresolvetheconflict,lessenedovertimebecauseofa widerangeoffactors.Theseincludeagradualweakeningofclericalauthorityand thechangingnatureoftheconflictitself.Additionally,thisstudyexploresthe differentrolesassumedbytheclergyandtheirbishopsinresponsetotheconflict. AsthepublicfaceoftheIrishCatholicChurchbishopsshoulderedmoreresponsibility,weremoreaccountable,andgarneredfarmorecriticismthantheirpriests whohadgreaterfreedomofactionandopinion.Ofcourse,viewpointson,and responsestotheconflictcanbeinfluencedbyanindividual ’sbackground, upbringing,location,andparochialexperience.Equally,theresponseofthe EnglishandWelshCatholicChurchtotheconflictoftendivergedfromthatof theIrishCatholicChurch.

⁹ IrishCatholic,4Feb.1993; ‘AnIrishliberationtheology:LearningfromtheUniversalChurch’ , JosephMcVeigh,CatholicChurchandIrishDiasporaConference,(London,2014);BreifneWalker, ‘TheCatholicChurchinIreland adaptationorliberation?’ , TheCraneBag,5(1981),77–8.

¹⁰ ArthurMarwick, TheSixties:CulturalRevolutioninBritain,France,ItalyandtheUnitedStates, c.1958–c.1974 (Oxford,1998),34;Gerd-RainerHorn, TheSpiritofVaticanII:WesternEuropean ProgressiveCatholicismintheLongSixties (Oxford,2015),61–82.

¹¹MauriceHayes, MinorityVerdict:ExperiencesofaCatholicPublicServant (Belfast,1995),117.

¹²MarianneElliott, TheCatholicsofUlster (London,2000),466–7.

D.GeorgeBoycehascalledCatholicism ‘oneoftheessentialingredientsof Irishness ’.¹³WhenCatholicemancipationdidnotcomeswiftlyaftertheActof Unionin1800–1801,R.V.Comerfordarguesitresultedinthecreationofa ‘modernnationalistmovementinwhichIrishnationalitywasreinventedwith Catholicismasitskeyidentifier ’.¹⁴ TheCatholicChurchsupportedCatholic emancipationanditappearedtoworkintandemwithmostnationalistgroups throughoutthenineteenthcentury.Yetthetwentiethcenturyrelationship betweenelementsofIrishnationalismandtheCatholicChurchasaninstitution isquiterevealingof,attimes,blatantanimositybetweenthetwogroups.¹⁵ Regardlessofthisdivision,themajorityofunionistsinNorthernIrelandbelieved ‘CatholicequalledNationalist’.¹⁶ Thisstudyseekstoaddresstheplaceofthe CatholicChurchinthisconflictandexaminewhetherCatholicismwasstillone ofthoseessentialingredientsinthe1970s,1980s,and1990s.

Traditionally,priestshaveoccupiedaspecialplaceattheheartofIrishCatholic communities.UnderthehierarchicalorganizationoftheChurch,bishopswere accountabletoRome,priestsaccountabletobishops,andthelaityaccountableto theirpriests.¹⁷ Priestshadcontactwiththeircongregationnotonlythroughthe religioussacramentsandatmomentsofgreatjoy,likebaptism,confirmation,and marriage,butaswellintimesofsadness,aidingthesick,andpresidingover funerals.Thepriestwasnotsimplyamoralandspiritualadvisorinthisquasiconfessionalstate,butwasconsultedonpolitical,economic,andsocialissues.¹⁸ Priests’ involvementinIrishpoliticshadlessenedaftertheCivilWarendedin 1923,andwhiletheystillurgedparishionerstovotewiththeirChristianconscience,theirpresenceinencouragingrebellionhaddiminished.¹⁹ Thepriest remainedarespectedpersoninCatholiccommunitiesand,sometimesbegrudgingly,acknowledgedfortheirappealsfornon-violenceinProtestantneighbourhoods.TheNorthernIrelandTroublesprovedtheHomeRuleadagefromthe 1880s: ‘ReligionfromRome,politicsfromhome’ mostlytobetrue.Throughout theconflict,Catholicslistenedtotheologicalperspectivespromulgatedfromthe pulpitbutprivatelyvotedforwhoevertheywished,evidencedintheminoritywho votedforSinnFéin(SF)afterthe1981hungerstrikes.Evenintheearly1970s, whenRichardRoseaskedinhissubstantivesurvey ‘ifyouwantedadviceona politicalquestion,whowouldyougotoforhelp?’,hefoundthatonly16percentof NorthernCatholicswouldapproachtheirpriest:mostpreferringalawyer,physician,orpolitician.²⁰ Bythetimeofthe1994cease fireandclericalchildabuse

¹³D.GeorgeBoyce, NationalisminIreland (London,1982),360.

¹⁴ R.V.Comerford, Ireland:InventingtheNation (London,2003),108.

¹

⁵ Boyce, Nationalism,317–18.¹⁶ Comerford, Ireland,117.

¹⁷ Inglis, MoralMonopoly,44.¹⁸ Inglis, MoralMonopoly,47.

¹⁹ SeeDermotKeogh, TheVatican,theBishopsandIrishPolitics1919–1939 (Cambridge,1986).

²⁰ SeeRichardRose, GoverningwithoutConsensus-AnIrishPerspective (London,1971)inGerald McElroy, TheCatholicChurchandtheNorthernIrelandCrisis,1968–86 (Dublin,1991),10.

revelations,priests’ seeminglyautomaticroleasmenofintegrityandmorally uprightandscrupulousadvisorshadbeentarnishedirreversibly.Theconflict beganwithdeferencetoclericalauthoritybutendedwithagreatlydiminished quotient.²¹In1968,theIrishCatholicChurchwasreelingfromtheeffectsofthe SecondVaticanCouncil.Itwouldtakeyearstoimplementthesechanges,withthe laityonlytakingalargerrolewithintheIrishChurchinthe1980s.TheIrish CatholicChurchwaschangingstructurallythroughouttheconflictbecauseof outsidefactors,includingVaticandirectivesandgrowingwesternEuropean secularization.²²

Thereisapropensityinthehistoriographytoprioritizecertainexplanations whenevaluatingthecausesandmotivationsfortheconflict.Historiansgrapple withitsorigins,favouringonespeci ficvalueormotivatorascreatingandcontinuingtheviolence.In1995,JohnMcGarryandBrendanO’Learyarguedreligion wasnotthemaindriver,claimingif ‘socio-economicinequalities,culturalor nationaldifferences,inter-staterelations...mustbeofsecondaryorno importance ...Wewill arguethatthosewhothinktheconflictisbasedonreligion arewrong. ’²³Marxistpoliticaltheoristsandsociologistshaveignoredreligion altogetherintheiranalyses.Conversely,FrankWrightandSteveBruceearlier providedexcellentstudiesonthecentralityofreligion.²⁴

Likewise,whileProtestantchurchesarefrequentlygroupedtogetherasasubject foranalysis,keydistinctionsremainbetweentheirviewpointsandexperiences.²⁵ SteveBrucehasarguedforacaseofIrishexceptionalismconcerningsecularization;namelythatunliketherestofEurope,Irelandclungtoreligionuntilthelate 1960s.²⁶ Classalsohasacrucialroletoplayinshapingexperientialrealities:a working-classboyontheShankhilldoesnothavethesameconcernsasaMalone Roadhousewife.TheviolenceandbloodshedinNorthernIrelandcannotbe explainedasaconflictrootedpurelyintensionsoverclass,gender,orreligion, butratherthroughacomplexinterplayofmultiplefactors.Thisolder(and politicallyinvested)historiography,withitsdesireforadefinitive,mono-causal explanationoftheoriginsoftheconflict,disregardsthefactthesecausesinteract. Partofthisimpetustoasserttheexplanatorycertaintyofoneattributeover

²¹A1968pollconductedamongyoungpeopleageseventeentotwenty-fourinNorthernIreland foundthatCatholicschosepriestsasthemostwellrespectedoccupationalgroup.SeeMcElroy, Catholic Church,10.

²²However,SteveBrucechallengesthisnotionofsecularizationinIreland;SteveBruce, ‘History, sociologyandsecularisation’,inChristopherHartney(ed.), Secularisation:NewHistoricalPerspectives (NewcastleuponTyne,2014),190–1.

²³JohnMcGarryandBrendanO’Leary, ExplainingNorthernIreland:BrokenImages (Oxford,1995), 171–2.

²⁴ SeeFrankWright, NorthernIreland:AComparativeAnalysis (Maryland,1987)andSteveBruce, GodSaveUlster!TheReligionandPoliticsofPaisleyism (Oxford,1986).

²⁵ SeeEricGallagherandA.S.Worral, ChristiansinUlster (Oxford,1982).

²⁶ SteveBruce, ‘Secularizationandtheimpotenceofindividualizedreligion’ , HedgehogReview, 8(2006),38.

anothermaystemfromapartisanneedtodealwiththepast:todemonstrate historianshavearoleinshapingapost-conflictsociety.²⁷ FortheTroubles, allhistoryis ‘publichistory’ andthenexusbetweenmemoryandhistoryreturns itssalience.Thereforeexplanationsoftheconflicthavebeenfoughtoverand ‘colonized ’ bythosewhoexperiencedtheconflict.

Classplaysamajorroleinthisstudywhenexaminedalongsidereligion, ethnicity,andmasculinity.Priestsasanexclusivelymale,educatedgroup,were construedas ‘superior ’ withintheirlaycommunities.Partitionservedto ‘restore theclergytopositionsofpoliticaldominance ’.²⁸ Thisbegantochangebutthe financialcostsoftrainingandjoiningthepriesthoodwerestillrelativelyhigh. Scholarshipsexistedtoaidable,less financiallyfortunatestudentstostudyat Maynooth,butthepricewasstilltoosteepformany.In1940,a£30depositofhalf tuitionfeesand ‘otherfees ’ neededtobepaidbeforeguaranteeingthestudent entryforthatyear.Students ‘nominatedtoafreeplace’ werestillrequiredtopaya £13deposit.²⁹ Therefore,priestsweregenerallybetteroffthantheirparishioners. Classandeducationaldivisionsdevelopedbetweenmembersofthehierarchyand theclergyaswell.Wealthierpriestswhoreceivedamorerigorous,oftengrammar school,educationandhadfamilyconnections,climbedhigherandfaster.³⁰ This becamelessofaproblembythelate1980sandearly1990saspriestlyordinations haddropped.Seminariansweremoredifficulttocomebysothebureaucratic climbmatteredless.Classdivisionswithintheclergyinfluencedtheirdiffering approachestothecon fl icttoacertainextent.Inthe1960s,amore heterogeneously-classedgroupofclergyemerged,conflictingwiththehierarchy becauseoftheirdifferentparochialexperiencesinthepost-VaticanIIChurch, ratherthanpurelyasaresultofclassdifferences.

Asecond,andarguablymoreinfluential,factoristhepowerofpersonalities (seeAppendixforindividualbiographies).Keyindividualsplayedcrucialrolesin alteringhowtheCatholicChurchrespondedtotheconflict.Whentheconflict began,CardinalWilliamConwaywasArchbishopofArmagh(seeAppendix). ConwaywasaquietmanwhohadlecturedatMaynoothinthe1940sand1950s andwastheologicallyconservative.Hissuccessorin1977,ÓFiaich,wasjustoneof manyindividualpriestswhohadamajorimpactontheconflict.Thepushand pullbetweenÓFiaichandBishopCahalDalyofDownandConnor(seeAppendix)inthe1980s,whichwillbediscussedinChapter4,remainsbutoneexample ofhowdisparatepersonalitiescouldcollectivelyshapetheChurch’ sresponse. DalysucceededÓFiaichasArchbishopofArmaghafterthelatter’sunexpected deathin1990,onceagainalteringthepositionofthehierarchyinresponsetothe

²⁷ IanMcBride, ‘Intheshadowofthegunman:IrishhistoriansandtheIRA’ , JournalofContemporaryHistory,46(2011),690–1.

²⁸ OliverRafferty, CatholicisminUlster1603–1983:AndInterpretativeHistory (London,1994),3.

²⁹ Kalendarium:CollegiiStiPatritii,(Dublin,1940–41),248.

³⁰ Elliott, CatholicsofUlster,466–70.

conflict.Thepowerofsubjectivitiesandopinionscannotbelimitedtomembersof thehierarchy,asmanypriestsbecamehouseholdnamesintheNorth,leavinga lastingmarkonconflictresolution.Whilemanyofthesepriestshadthesame goal anendtotheviolence theirmethods,publicpersonas,andtheologicaland pastoralapproachesbroughtthemintoconflictwithProtestantclergy,unionists, andparamilitaries,aswellaseachother.

ThetraditionalnarrativeoftheChurchintheTroubleshasfocusedsolelyon theIrishCatholicChurch.³¹Thisstudybroadensourcollectiveunderstandingby introducinganalysisoftheEnglishandWelshCatholicChurch.Ecumenical relationsandendeavoursinEnglandwereseparateanddifferentlyframedto thoseinNorthernIreland.Therefore,thisstudyemploysamixedmethod approach.TheIrishCatholicChurch’sresponsetotheconflictmustbeviewed asanentangledhistory.Theexistinghistories,whichwillbediscussedinthenext section,merelyevaluateinasomewhatcircumscribedfashionthereactionofthe IrishCatholicChurchtotheconflict.³²Thisapproachispartialandoverly parochial;theProvisionalIrishRepublicanArmy(IRA)hadabombingcampaign inEngland,andtheEnglishandWelshCatholicChurchwasfrequentlyaskedfor theirthoughtsontheexcommunicationofIRAmembers.Itisfutiletostudythe Troublesintermsofnationalnarratives,astheconflictspilledovernational borders.Foranentangledhistory,asMargritPernauargues: ‘Everytransferis atwo-wayprocess,whichinfluencesnotonlythesenderbutthereceiver ’.³³ CommentsontheconflictbyEnglishbishopsdirectlyimpactedupontheperceptionof,andthereactionto,theIrishCatholicChurch.Thisisnotsimplya comparativehistory,asJürgenKockaacknowledges,becausetheseunitsofcomparison ‘cannotbeseparatedfromeachother’.³⁴ Englishbishops’ opinionson suicideandexcommunicationdifferedfromtheirIrishcounterpartscausing confusionamongthelaity:thisdirectlyimpactedupontheabilityoftheIrish CatholicChurchtomediatetheconflict.TheChurches’ closeproximityandthe IrishdiasporainBritainledtofrequentinteractions.ExamininghowtheCatholic Churchesrespondedtotheconflictrevealsdifferingapproachesoneithersideof theIrishSea.

Thisstudyarguesitiscrucialtoevaluatetheintertwinedrelationshipbetween theIrishandEnglishandWelshCatholicChurchesinrelationtotheconflict inNorthernIreland.IfhistoriansfocusonlyontheIrishCatholicChurch’ s

³¹OliverRafferty,GeraldMcElroy,MarianneElliott,TomInglis,andMaryKenny,whoseworksare discussedbelow,focustheirstudiestotheIrishCatholicChurch;Elliott, CatholicsofUlster;McElroy, CatholicChurch;Inglis, MoralMonopoly;Rafferty, CatholicisminUlster;MaryKenny, Goodbyeto CatholicIreland (Dublin,2000).

³²SeeMcElroy, CatholicChurch;Elliott, CatholicsofUlster;Kenny, GoodbyetoCatholicIreland; Rafferty, CatholicisminUlster;Inglis,MoralMonopoly

³³MargitPernau, ‘Whitherconceptualhistory?Fromnationaltoentangledhistories’ , Contributions totheHistoryofConcepts,7(2012),4.

³⁴ JürgenKocka, ‘Comparisonandbeyond’ , HistoryandTheory,42(2003),41.

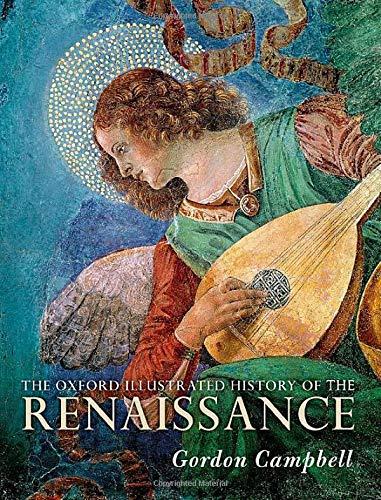

Key

Catholic Dioceses of Ireland

Republic of Ireland

Northern Ireland

Figure1 MapofCatholicChurchDioceseBoundaries

Source:EoinO’Mahony.

responsestotheconflict,(seeFigure1fordiocesanboundaries,whichdonot directlyoverlapwiththeIrishborder),theymissoutonafullerhistoryoftherole ofreligiousinstitutionsintheconflict.Aswillbeexplored,theEnglishandWelsh hierarchydisagreedwiththeIrishhierarchyonIRAfunerals,excommunication,

Cork & Ross

Kerry

Cloyne

Limerick

Cashel & Emly

Waterford & Lismore

012.5255075100 Kilometers

Ossory

Killaloe

Galway & Kilmacduagh

Clonfert

Tuam

Achonry

Killala

Elphin

Kilmore

Clogher

Raphoe

Derry

Down & Connor

Dromore

Armagh

Meath

Dublin

Ferns

Kildare & Leighlin &

Ardagh & Clonmacnoise

andthestatusofIrishprisoners.Britishnewspapersreportedthesesquabbles, especiallyduringthe1980-81hungerstrikes.³⁵ IftheChurchcouldnotagree,how coulditshapeopinionsofthefaithful?TherewerealsoCatholicBritishArmy soldiersstationedinNorthernIreland.Theiractionsand,attimes,theirdeaths forcedwiderCatholicChurchestorespondtotheconflict.

SourcesandtheirLimitations

AccessingdiocesanarchivesinIrelandhasoftenprovedchallengingtohistorians. Many filesfromtheperiodareyettobemadeavailabletoscholars.Asaresult,this studyhassupplementedIrishsourceswithEnglishdiocesanarchivalmaterial. Diocesesacrosstheseislandsgenerallykeepaone-hundred-yearrulefromthe dateofapriest’sdeath,leavingmanyoftherelevantpapersunavailable.Documentsconcerningthehierarchy,however,areregulateddifferently.TheIrish CatholicChurchoftenreleasesdocumentsrelatingtoaparticularbishopthirty yearsafterhisdeath.TheEnglishandWelshCatholicChurchoperatesathirtyyearrulefromthedatethatdocumentswerecreated.Insomecases,moresources havebecomeavailableearlieratabishop’sdiscretion.³⁶ Englishdiocesanarchives havethereforeprovedfruitfulforthisstudywithamajorityofcorrespondence betweentheIrishandEnglishandWelshbishopsavailableuntil1988.

BritishandIrishgovernmentarchiveshavebeenquarriedextensivelyforthis study.ThesedocumentsrevealrelationshipsbetweenChurchleadersandBritish andIrishgovernmentofficialsonavarietyofissues,including:perceptionsof clericalauthority;politicalandpastoraltensionsamongbishopsandclergymembers;andameasureofgovernmentthoughtconcerningthenatureoftheCatholic Churchintheconflict.TheNationalArchivesofIreland,Dublin,operates athirty-yearrule,whileTheNationalArchives,inKew,Surrey,ismoving fromathirty-yearruletowardsatwenty-yearruleconcerningUKgovernment documents.³

⁷ Generallyspeaking,whileIrishgovernmentofficialsdemonstrated muchmorereverenceforCatholicChurchleaders,Britishpoliticiansandcivil servantshandledbishopsandpriestswithadegreeofsuspicionandscepticism.

Thisstudybenefitsfromoraltestimonyfrompriests,bishops,politicians, womenreligious,andformerparamilitaries,whichhashelpedto fillvitalgaps leftbyincompleteorclosedarchives.Thishasprovidedotherwiseinaccessibleand

³⁵ SeeMargaretScull, ‘TheCatholicChurchandthehungerstrikesofTerenceMacSwineyand BobbySands’ , IrishPoliticalStudies,31(2016),282–99.

³⁶ Atthetimeofpublication,onlyfourboxesofCardinalWilliamConway’sdocumentswere releasedtotheCardinalTomásÓFiaichLibraryandArchive(CTOMLA).MostofCardinalÓFiaich’ s papersshouldbereleasedin2020.

³⁷ Atthetimeofsubmission,theNationalArchivesofIreland(NAI)hadreleased filesuntil1986. TheUKNationalArchives(TNA)hadopeneddocumentsconcerningNorthernIrelanduntil1988.

illuminatingpersonalinsightsintotheconflictandwassupportedbyethics clearance.³⁸ Inparticular,myinterviewsamongclergymenandwomen,aswell asbishops,revealedagroupdividedonmanyissues.Existingbroadcastinterviews supplementedthismaterial,allowingforanalysisofperspectivesofdeceasedor unwillinginterviewees.

AnAppendixdetailsbiographicalinformationoftheimportantclerical figures intheconflict.Suchalist,akindof personaedramatis,didnotexistpreviouslyand featureswell-knownpublichierarchy figuresandlesser-knownmembersofthe clergy.ThisAppendixisitselfanoriginalscholarlycontributiontoourknowledge asmanyofthese figureshavenotbeensubjecttoseparatescholarlyworksorhave entriesintheDictionaryofNationalBiography.

From2014until2018,DrDianneKirbyandPhDstudentBriegeRafferty conductedgroupinterviewswithwomenreligiousinvolvedintheconflict.³⁹ ThereweremorewomenreligiousthanpriestsorbishopsintheIrishCatholic Church.KirbyandRafferty ’sforthcomingpublicationswillchangeexistingnarrativesoftheChurch ’sroleintheconflictbyincorporatingtheperspectivesofthis oftensilentmajority.⁴⁰ Theconflictaffectedwomenreligiousaswell.Inaddition toemotionaltraumasufferedbymany,SrCatherineDunnediedasresultof herinjuriesfollowingaroadsidebombinginJuly1990.⁴¹Threeexceptions areSrSarahClarke,SrGenevieveO’Farrell,andDrGeraldineSmythOP(see Appendix)whoseperspectivesareanalysedthroughout.TomInglisdescribed womenreligiousasthe ‘silent,solidfoundationofmodernIrishCatholicism ’ , ⁴² workingonpeaceprojectsandfundraisingforCatholicrefugees.Thereleaseof KirbyandRafferty’ s findingsandthegradualopeningofreligiousorderarchives willcreateopportunitiesforthoroughstudyofwomenreligious’ parochial,grassroots,andoftenunrecognizedrolesintheconflict.AsaconsequenceofKirbyand Rafferty’sstudyandjustifiedconcernsaboutduplication,fewerwomenreligious werewillingtobeinterviewedforthisstudy.

Thisstudyreliesonamixedmethodapproach,incorporatingcontemporary newspapers,oralhistorytestimonies,memoirs,andreligiousandgovernment archivalresearch.TheBritishandIrishCatholicnewspapersconsultedincluded:

³⁸ King’sCollegeResearchEthicsCommitteeRef:REP/13/14–10andNationalUniversityofIreland, GalwayRef:18-Sept-22.

³

⁹ http://globalsistersreport.org/column/justice- matters/conversations-between-sisters-belfastregarding-%E2%80%98-troubles%E2%80%99-25581

⁴⁰ BriegeRaffertyandDianneKirby, ‘Sistersinthe “Troubles” , DoctrineandLife, 67:1,(January 2017),pp.2–12; SistersoftheTroubles,BBCNewsWorldService,25March2018,https://www.bbc.co. uk/programmes/p0623s43.RaffertyandKirbywerealsoapartofthisBBCradioprogramme.Rafferty’ s doctoralthesisisentitled ‘Caughtinthecrossfire:CatholicreligioussistersandtheNorthernIreland Troubles1968–2008’

⁴¹ ‘RevisitingthePast:CatholicReligiousSistersandtheConflictinNorthernIreland’,Briege Rafferty, WritingtheTroubles,19Nov.2018,https://writingthetroublesweb.wordpress.com/2018/11/ 19/catholic-religious-sisters/ ⁴²Inglis, MoralMonopoly,52.

theliberalprogressive TheTablet; TheUniverse,whichhadthelargestreadership; themainlyBritish-focused CatholicHerald;andtheIrish-focused IrishCatholic ThesepapersprovidedreaderswithspecificinformationontheCatholicChurch inbothBritainandIreland,oftenreportingstatementsbythehierarchyinfull. TheTablet openlyvoicedcriticismandregularlyfeaturedarticlesbypriestswith morerevolutionaryideas.Whereas TheUniverse, CatholicHerald,and Irish Catholic didnotdeviatefromtraditionaltheologicalteachingsandadvocated moreconservativepoliticalpositions.AnalysingarangeofCatholicnewspapers helpgiveusanunderstandingofhowreligiously-mindedIrishandBritish Catholicswereinformedaboutthewiderconflict,thusaddinganotherdimension tothisstudy.

Despitethepublicationofmemoirsbypolitical figures,fewstudiesanalysing thehistoricalimportanceofautobiographicalaccountsexist.Oneofthefew examplesisStephenHopkins’ bookwhichidentifiestheimpactrepublicanshad inshapinga ‘publichistory’ narrativethroughtheirpublications.However, Hopkinsexcludesmemoirsbyreligious figures.⁴³Attimes,clergymembers unhappywiththechoicesoftheinstitutionalCatholicChurchhaveusedmemoirs toairgrievanceswiththeleadership,forexampleFathersJoeMcVeigh,Des Wilson,andPatBuckley(seeAppendix).⁴⁴ Inotherinstances,memoirshave raisedawarenessofareasofcontentionandthoseintheCatholiccommunity whosoughttoenactchange.OneexampleistheactivismofSrClarke,through herworkwithIrishprisonersinBritain. ⁴⁵ Aswithoralhistory,memoryand personalizedperspectivesplayaroleinsuchpublicationsandassuchmustbe carefullyinterrogated.Likeallsources,memoirmaterialisbesttriangulatedwith othersourcesinthecourseofitscritique.Evenwhenthenarrativesinmemoirs donotcorrelateorreinforcewrittenevidence,theyarestillusefultoevaluate perspectives.

Thesesourcematerialscollectivelyformthe firstcriticalstudyoftheIrish,and EnglishandWelshCatholicChurchesthroughouttheconflict.Theyallowan analysisofthecomplexinteractionsofbelief,religiousauthority,andpolitics acrossthreedecades.Sourcesindiocesanarchivesoftenprivilegethehierarchy’ s perspectiveandthisstudyacknowledgesthisstartingpointandinstitutional perspective.Aswillbediscussedfurther,anindepthanalysisoflaityviewshas notbeenpossibledespitetheirimportancetotheCatholicChurchstructureasa whole.

⁴³StephenHopkins, ThePoliticsofMemoirandtheNorthernIrelandConflict (Liverpool,2013).

⁴⁴ PatBuckley, AThornintheSide (Dublin,1994);JosephMcVeigh, TakingaStand:AMemoirof anIrishPriest (Cork,2008);DesmondWilson, ADiaryofThirtyDays – Ballymurphy – July–December, 1972 (Belfast,1973);DesmondWilson, TheChaplain’sAffair,(Belfast,1999);DesmondWilson, The WayISeeIt,(Belfast,2005).

⁴⁵ SarahClarke, NoFaithintheSystem:ASearchforJustice (Dublin,1995).

⁴⁶ ForstudiesoftheCatholiclaityduringtheconflict,seeElliott, CatholicsofUlster,371–428.

Historiography

IanMcBrideargueshistorianshavelongsoughttodispelthemythsthathave sustainedtheProvisionalIRA.Despitemanyhistoriansoftheconflictcoming fromNorthernnationalistorunionistbackgrounds ‘veryfewcouldbedescribed asunionistornationalisthistorians’ . ⁴⁷ Theirwritings,fashionedfromtheirlived experiences,haveplayedakey ‘roleinreshapingthepublicdiscourseonNorthern Ireland’ . ⁴⁸ Perhapsunsurprisingly,theoriginsoftheconflicthavereceivedsignificantacademicattentionprimarilyframedbyanadjudicationofwhetherthe Troubleswererootedinsectarianorethno-nationalisttensions.⁴⁹ Byincluding discussionoftheCatholicChurchasareligiousactorwithoutengaginginthis overworkeddebate,thisstudydeciphersthemultifacetedroleoftheCatholic Churchthroughouttheconflict.

TheCatholicChurch’spositionandinfluencewithinIrishCatholiccommunitieswasfarwiderreachingthananystatisticalanalysesofMassattendancescould evershow.TheChurcheffectivelycreateditsownstatebyassistingwithhousing, controllingeducation,andcreatingopportunitiesforleisure.Theinstitution traditionallyactedasguardianforitsfollowers,andthusprovidedaself-help traditioninDerry aselsewhere remainingcloselyconnectedtoCatholic religiouslife.⁵⁰ CatholicsinBelfastsharedasimilarconnectiontotheChurch.

A1969surveyconductedamongProtestantsandCatholicsinEastBelfastshowed Catholics ‘hadwarmerfeelingsfortheirchurchthanforanyotherorganization, group,politicalparty,orpoliticalleader’ . ⁵¹TherewereCatholichospitals,schools, andvoterregistration,whichallreliedonlayvolunteersandChurchfunds.The ChurchalsosupportedtheCreditUnionmovement,whichwas ‘Catholicin origin’ accordingtoDerrybranchtreasurer,JohnHume.⁵²Asaresult,theChurch spoketoclassissuesanddevelopedaprecedentforprovidingCatholicswith financialaidinNorthernIreland.Moreover,theChurch’semphasisoneducation, especiallyafterthe1947EducationAct,wasanotherrouteforCatholicsocial mobility.Throughinsistingonsegregatedreligiouseducation,theChurchsecured controlofthatvitalaspectofparishioners’ lives.⁵³However,disagreementover educationexistedwithintheChurch,withaccusationsthatthemoreconservative hierarchypreferredgrammarschoolsbyindividualpriestsandwomenreligious

⁴⁷ McBride, ‘IntheShadowoftheGunman’,690.

⁴⁸ McBride, ‘IntheShadowoftheGunman’,690.

⁴⁹ McBride, ‘Intheshadowofthegunman’,701;McGarryandO’Leary, ExplainingNorthern Ireland,250.

⁵⁰ Elliott, CatholicsofUlster,466.

⁵¹SeeMalcolmDouglasJr, ConflictRegulationvs.Mobilisation:TheDilemmaofNorthernIreland, PhDThesis,ColumbiaUniversity,1976inMcElroy, CatholicChurch,10.

⁵² DerryJournal,14Feb.1961inSimonPrinceandGeoffreyWarner, BelfastandDerryinRevolt: ANewHistoryoftheStartoftheTroubles (Dublin,2011),21.

⁵³EdwardDaly, Mister,AreYouaPriest? (Dublin,2000),119.

likeSrGenevieveO’FarrellofStLouise’sComprehensiveSchoolinWestBelfast, whoadvocatedforrigorouseducationatalllevels.⁵⁴ Aspertainstohighereducation,priestspressedforauniversityinDerry,althoughthisactionfailed.⁵⁵

InDerry,priestsworkedtoalleviatehousingpressures.FatherAnthonyMulvey (seeAppendix)workedwithpoliticiansandcommunityactivists,likeHumeand PaddyDoherty,tofoundtheDerryHousingAssociation(DHA).⁵⁶ TheDHA attemptedtoalleviatehousingpressuresbytakingoverbuildingsandconverting theminto flatswithreasonablerates.Housingassociationslikethiswerevitalby the1960sasachronichousingshortagemeantmanyCatholicswerebeingpushed outofDerrycitycentre.⁵⁷ Therefore,incontrollingreligiousandcommunity resources,andsocialinteractionsforNorthernCatholics,thedifferentialbetween thosewhowerepractisingCatholicsandthosewhosawthemselvesasculturally Catholicwasincreasinglyundefined.

Thetheorythattheconflictwasbasedonethno-nationalisttensionshasbeena prevailingone.JohnMcGarryandBrendanO’Learyarethemainchampionsof thisapproach,arguingethnicitywasthecatalystoftheTroubles.Yettheiridea thatethnicityis fixedandunchanging,builtoninheritedculturaldifference,is reductionistatbest.⁵⁸ McGarryandO’Learyargueagainstculturalexplanationsof theconflictpromotedbyMarianneElliott,RuthDudleyEdwards,RoyFoster,and OliverMacDonagh.⁵⁹ Theydownplayreligionasanactive,salient,andoperationalfactor,preferringtoseeitasamarkerofsocio-economicandethnic differencebetweencommunities.

Incontrast,JosephRuaneandJenniferToddofferamoreconvincinganalysis. TheyargueNorthernIrelandhasan ‘evolvingsystemofrelationships’ whichhelp reinforceeachother.⁶⁰ ForRuaneandTodd,theoriginsoftheconflictcanbe foundattheintersectionsofreligion,ethnicity,ideology,andcolonialism.Inother words,theTroubleswererootedincenturiesofcommunitydivisionformedby politicalandsocialinequalities.RuaneandToddchallengetheideaofthe ‘grand narrative’ yettheiranalysisplacestheoriginsofdiscontentasfarbackasthe sixteenthandseventeenthcenturies.Ethnicityisjustonefacetofthisnarrative.⁶¹ Theauthorscreateanargumentbasedonthesituationalaswellaslongitudinal:

⁵⁴ JohnRae, SisterGenevieve (London,2001),111–13.

⁵⁵ DerryJournal,2Feb.1965inPrinceandWarner, BelfastandDerry,24–5;InterviewwithMgr RaymondMurray,11Feb.2014.

⁵⁶ PrinceandWarner, BelfastandDerry,21.

⁵⁷ PrinceandWarner, BelfastandDerry,22–3.

⁵⁸ McGarryandO’Leary, ExplainingNorthernIreland,250.

⁵⁹ McGarryandO’Leary, ExplainingNorthernIreland,227–30.

⁶⁰ JosephRuaneandJenniferTodd, TheDynamicsofConflictinNorthernIreland:Power,Conflict andEmancipation (Cambridge,1996),8.

⁶¹SeeJosephRuaneandJenniferTodd, ‘Therootsofintenseethnicconflictmaynotinfactbe ethnic:categories,communitiesandpathdependence’ , EuropeanJournalofSociology,45(2004), 209–32;JosephRuaneandJenniferTodd, ‘Pathdependenceinsettlementprocesses:Explaining settlementinNorthernIreland’ , PoliticalStudies,55,2007,442–58.