1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rustomji, Nerina, author.

Title: The beauty of the houri : heavenly virgins, feminine ideals / Nerina Rustomji. Description: New York : Oxford University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020058292 (print) | LCCN 2020058293 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190249342 (hardback) | ISBN 9780190249366 (epub) | ISBN 9780190249373 | ISBN 9780190249359

Subjects: LCSH: Paradise—Islam. | Islamic eschatology.

Classification: LCC BP166.87 .R87 2021 (print) | LCC BP166.87 (ebook) | DDC 297.2/3—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020058292

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020058293

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190249342.001.0001

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

To

Shehriyar

and the city of New York

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I HAVE BENEFITED FROM ALL kinds of support at many stages.

Librarians provided access and encouragement. Carmen Ayoubi at the American Center of Oriental Research in Amman, Jordan, assisted at an early stage of the project. Jay Barksdale at the New York Public Library, where I worked in the Wertheim Study and Soichi Noma Reading Room and participated in the MARLI program, was also an early supporter. My interview with him and subsequent tea service reminded me of the civic value of the public library system whose librarians, including Melanie Locay and Carolyn Broomhead, made this book possible. Ray Pun has been an all-around media resource.

Colleagues offered useful references and made helpful suggestions. I would like to thank Dick Bulliet, Ayesha Jalal, and Denise Spellberg for their early and continued support for the project. Scholars of Islamic history, Islamic religion, and Muslim societies have helped me expand my ideas. They include Durre Ahmed, Dana Burde, David

xii | A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

Cook, Adam Gaiser, Matthew Gordon, Sebastian Günther, Kathryn Hain, Juliane Hammer, Amir Hussain, Akbar Hyder, Pernilla Myrne, Lisa Nielson, David Powers, Frances Pritchett, Tahera Qutbuddin, Dagmar Riedel, Walid Saleh, Eric Tagliacozzo, SherAli Tareen, Shawkat Toorawa, and Jamel Velji. Scholars of American and English history have guided me through contexts and literatures and have offered useful advice. They include Dohra Ahmad, Jacob Berman, Hasia Diner, Kathleen Lubey, Todd Fine, Mitch Fraas, John Gazvinian, David Grafton, and Christine Heyrman. Other scholars have helped me interpret traditions of the ancient Near East, late antiquity, comparative religion, and South Asia. They include Amy Allocco, Carla Bellamy, Richard Davis, Lynn Huber, Cecile Kuznitz, Ruth Marshall, Scott Noegel, Shai Secunda, and Joel Walker. Indispensable assistance with du Loir and his context was provided by Michael Harrigan, Ioanna Kohler, and Michael Wolfe. I benefited from the intellectual community of academic list-serves, including Adabiyat, H-Atlantic, H-Islamart, H-Mideast-Medieval, H-Mideast-Politics, H-World, and Islamaar. My anonymous reviewers offered useful advice and constructive commentary, and I am grateful for their suggestions.

Generous listeners at presentations and conferences asked sharp questions and shared valuable insights. These exchanges took place at the American Council of Oriental Research, Bard College, Barnard College, Columbia University, City University of New York Graduate Center, Cornell University, Franklin and Marshall College, George Mason University, International Congress of Medieval Studies, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Middle East Studies Association, New York Public Library, Organization of

CKNOWLEDGMENTS

American Historians, University of Göttingen, University of Pennsylvania, University of Texas, University of Washington, and Yale University. Additionally, I would like to thank Cindy Postma for inviting me to King’s College, where questions from members of the audience challenged me, gave me much to reflect upon, and showed me the value of intellectual exchange that bridges the divide between scholarly and popular worlds.

Institutions provided vital support. The book started with an American Council of Learned Societies fellowship in 2007–2008. Additionally, I held a research fellowship at the American Center of Oriental Research, and thank Barbara Porter for her wonderful engagement over the years. While the idea of the book started while I was working at Bard College, the book was researched and written at St. John’s University where I held a Summer Research Fellowship in 2011. My students at St. John’s University shared meaningful perspectives during classroom discussions. I also benefited from the counsel of History Department colleagues, including Dolores Augustine, Frances Balla, Mauricio Borrero, Elaine Carey, Shahla Hussain, Tim Milford, Phil Misevich, Lara Vapnek, and Erika Vause.

Friends and strangers were part of the process of researching and writing the book. There are more houri jokes in the universe than one can imagine, and over the years I have heard many of them, thanks to enthusiastic interlocutors. My research may have started with the inventory of Internet jokes, but a joke does not make a book. I would not have completed the manuscript without the generosity and assurance of Kristen Demilio, Jean Ma, and Laura Neitzel who helped me refine my thinking, edited drafts, and encouraged at every turn.

xiv | A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

The book is made possible because of Oxford University Press. My editor, Cynthia Read, has been a steady champion, and her insight and judgment have been invaluable. Zara Cannon-Mohammed, Cameron Donahue, Marcela Maxfield, and Christian Purdy have been helpful collaborators. Dorothy Bauhoff, Julie Goodman, and Cynthia Read edited the manuscript with keen eyes.

I was able to research and write the book because of the bracing love of Aban, Purvez, and Arish, the witty joy of Shehriyar, and the whimsy of Azad and Tahmir. I was also inspired by the city of New York, whose beauty is expressed through verve, humor, and civic connection. The beauty of the city was visible on September 11th when the world was watching, and it is present today when no one is looking. This book was motivated by that day, drafted in city libraries, shaped by city students, and encouraged by city neighbors. It could not have been written, with such resonance, anywhere else.

INTRODUCTION

THE HOURI IS AN UNKNOWABLE, otherworldly beauty. All faithful Muslim men are said to be awarded these female companions—hur al- ʿin in Arabic, houris in English—in the ineffable realm of paradise. Since the houri is not an earthly being, lived experiences cannot attest to her beauty. She remains a cosmic promise. Writers attempted to explain her large dark eyes and her virginal, untouched purity. Their imaginings of her physical form demonstrated a fascination with the ultimate gendered reward—a female companion for a male believer. What makes the houri an ideal beauty, by contrast, is far more complex than a list of her attributes. This is my September 11th book, but I did not know it until 2004. I opened The New York Times to find an opinion piece by Nicholas Kristof entitled “Martyrs, Virgins and Grapes.” The column linked the figure of the houri with the lack of freedom of speech in Muslim societies. It argued that houris are really white grapes, but that most Muslims are unfamiliar with this interpretation because they are not free to question their religious texts. The column referred to the theologian al-Suyuti, who died in 1505. I was struck by this reference. As a new assistant professor, I questioned what students needed to know and why they needed to know it. I wondered whether The New York Times readers had

encountered al-Suyuti before, and why they needed to learn of him that day. I recognized a tension. The houri is often referenced in popular texts, but there was not a developed scholarly literature that explains her significance. This book began as an attempt to address both scholarship and popular discourse about the houri. It has expanded into a larger examination of the houri by theologians, grammarians, travelers, journalists, intellectuals, and bloggers. The question that has guided me is not whether Kristof’s argument about scriptural interpretation was correct, but why references to these heavenly virgins would have been recognizable to his readers at all. I wanted to understand how “Islamic virgins” have become part of the American vocabulary about Islam.

As I began to study the prevalence of the houri in print and online media, I became aware of a vast and complex set of historical reflections about the houri. Houris appear in genres of Arabic theology and Arabic and Persian poetry, but they were also frequently found in English and American literature until the early twentieth century. The history of the houri, then, is not an exclusively Islamic history. The figure of the houri inspired writers, readers, artists, and viewers in many different times and contexts. This chronicle of inspiration is not a continuous narrative. It has multiple beginnings, some lulls, and no clear end. Yet, at each point of development, the houri is a topic of fascination. She is a cosmic being, but she also presents an image of human feminine perfection. That promise of perfection transformed the houri into a model that had potential to inspire both men and women. The book ranges from the seventh to the twenty-first century, but its starting point is found in the recent American past of September 11, 2001, which for many readers may mark their first encounter with the image of the houri in

popular media as a heavenly virgin waiting to reward the perpetrators of the attacks on the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and United Airlines Flight 93.

This book uses theological and literary sources and analyzes them through discursive and contextual analysis. It also examines contemporary media representations of the houri that have emerged on online digital platforms such as YouTube in the last two decades. The sources often took forms that I did not anticipate. A letter said to be written by September 11th hijacker Mohamed Atta was a dramatic piece of evidence offered by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and subsequently was published by newspapers to account for evidence of and motivation of the hijackers. Now it is a small, mostly ignored display in the National September 11 Memorial and Museum in New York City. The videos made by jihadi groups and globally disseminated via YouTube were evidence of a vibrant traffic of jihadi recruitment efforts. Now that technology companies have become more circumspect about content, the circulation of such videos has been reduced. In fact, some videos in my research can no longer be accessed. While I have studied many of them, I only discuss the ones that I was able to archive digitally. Meanwhile, other sources that demonstrate the American and English fascination with houris await consideration.

The houri originated in Islamic texts, developed in European ones, and gained a new life in digital media. When we survey the writings about houris, we see creative interpretation and engagement across times, cultures, writers, and texts. If there is a significant limitation of the book, it is that it studies the written productions of urban people. The texts were designed for theological elite in Islamic circles and cosmopolitan elite in Europe and the

United States. Similarly, the videos considered here are designed for digitally connected people. While accessing digital productions today may not require the same networks of power as accessing the texts of the past, the digital productions do require the capacity to use technology and be connected to the web. Even with this limitation, the Internet offers the potential to record attitudes, assumptions, thoughts, reactions, and prejudices for digitally connected populations.

A QUESTION OF ORIGINS

Scholars have tried to understand the houri through comparison with other religious traditions. The quest for origins is challenging since it is unclear what a houri really is. Assumptions about the purported source of origin lead the argument, rather than close textual study. In these modes of reasoning, scholarship points to origins in Zoroastrian, Jewish, and Christian eschatological traditions. In the Zoroastrian religion, after believers die, they are said to cross the Chinvat Bridge. As the soul crosses, the soul learns of its everlasting place. If met by a beautiful female, the soul sees the embodiment of its good deeds, or Daena, and earns a place in paradise. If met by an ugly hag, the soul sees the embodiment of its bad deeds and earns a place in hell. Some scholars suggest that the houri may have been borrowed from this Zoroastrian belief.1 Another theory locates the origin of the houri in early stages of Jewish eschatology when sexual pleasures were part of paradise.2 In both the Zoroastrian and Jewish origin theories, the feminine beings have a spiritual and an aesthetic dimension.

Theories that involve Christian origins depend on different assumptions about the material world. One theory turns toward ideas about angelology or the heavens, where the houri is a celestial being who is spiritually pure and without the capacity for physical beauty or the desire to please.3 The houri, in effect, is equated with a feminine angel. The theory focused on the Syriac texts of St. Ephrem accords a more material dimension to paradise and links the houri with the image of a paradise garden.4

Charles Wendell refreshingly argues for an Arabian origin and suggests that the houri is the “most Arabian” feature of Islamic paradise.5 He argues against foreign origins of the houri, noting that it is worth looking for parallels. For example, if the Zoroastrian religion was the inspiration for the figure of the houri, then the dichotomy should also be carried over, and an ugly hag should appear in Islamic eschatology as the antithesis of the houri.6 Wendell suggests instead that the origin may be found in Arabian taverns or drinking houses, and he turns to Arabic poetry to explain the meaning of the houri.

Interestingly, the theories about the houri’s origins often misrepresent the relationship between the material and spiritual world in Islam. The houri is misunderstood either as a sensual being, at the expense of spirituality, or as an angel without any physical capacity. Scholars who make these linkages understand the houri through her physical, sensual, or sexual meanings, but their theories do not account for the nature of aesthetics in the Islamic afterworld. Their discussions either center on physical form without acknowledging spiritual perfection or invalidate the possibility of any physicality at all. They read the houri primarily as a woman designed for men’s pleasure rather than a feminine being who

exemplifies the possibilities of an aesthetically and spiritually pure realm. The scholarship on the houri sheds light on the frameworks that scholars brought to understand a feminine being who was never fully defined in the Qur ʾan and Islamic theological texts.

CHAPTERS

The six chapters of The Beauty of the Houri offer two developing perspectives. The first perspective focuses on the European, English, or American views of the houri from the sixteenth to the twenty-first century. The second perspective offers a view of classical and contemporary Islamic uses of the houri from the seventh century to the present. These two perspectives are not in opposition. There is not one definitive meaning of the houri in either European and American or Islamic literature. Instead, there are a number of meanings that lead to different driving questions. The clustering of the chapters is an organizational scheme to account for change in context and genre and to appreciate how contemporary thinkers draw on different sources to present visions of a twenty-first-century houri.

The book starts with discourse after September 11th and ends with contemporary Muslim discourse on the Internet. In between, the chapters show the antecedents of these two modern discourses in earlier European, American, and Islamic histories. The first three chapters introduce the American viewpoint and its legacies and suggest that the fascination with the houri involves using feminine models to determine and judge the value of Islam. The houri became a distinctly European and American

symbol that may have been developed from Islamic texts, but far exceeded their parameters and significance. The final three chapters present an Islamic perspective of the houri and suggest that there has always been an ambiguity about the houri in the Qur ʾan and Qur ʾanic commentaries. It is precisely the lack of clarity about the meaning of the houri that has led to such vivid depictions in historical accounts, theological texts, online videos, and contemporary discourses. Unlike the writers who claim that Muslims lack a tradition of scriptural interpretation, Chapters 5 and 6 show that there is vibrant Islamic discourse about the meaning of the houri in the twenty-first century. This discussion suggests the possibility of gender parity in paradisiacal rewards in which Muslim women are promised a reward equal to that of Muslim men who are granted houris.

Chapter 1, “The Letter,” studies the most consequential recent mention of the houri, the purported letter of September 11th hijacker Mohamed Atta, and shows that media fascination with the houri is related to American reactions to the events of September 11th. It looks at the function of the houri in the letter and then turns to how media have understood the passages about the houri. It introduces two related arguments commonly found in US news media. The first is that Islam needs a form of scriptural interpretation so Muslims can be able to live in free, secularized societies. The second is the white grape theory, the argument that references to houris are really references to white grapes or raisins, and not to female companions awaiting men in paradise. In tracing the impact of the theory, the chapter turns to the diffusion of the houri in comedies, satires, and novels.

Chapter 2, “The Word,” shows how the English and French fascination with Islam involved interpretations of the houri and her meanings. The chapter surveys sixteenthcentury polemics about Islam, seventeenth-century French travel writings, and eighteenth-century English literature about the Muslim East. In describing these early modern exchanges, which involved Turks in England and the English and French in the Ottoman Empire, the chapter depicts the widening of the English and French worldview. By the eighteenth century, “houri” was used as a way to describe superlative feminine beauty, even while views of Islam and Islamic empires were ambivalent.

Chapter 3, “The Romance,” demonstrates how nineteenthcentury literature transcended religious frameworks and questioned the nature of male authority and feminine purity. This chapter shows that, although the houri may have been based on assumptions about Islam, the term eventually was applied to Jewish and Christian women. In Romantic tales and poetry and captivity narratives, the houri appeared in different forms. There is a Byronic houri, a Victorian houri, and even a Kentucky houri. In these texts, the houri signifies the ideal female, irrespective of religion or region.

Chapter 4, “A Reward,” presents Islamic theological and historical texts about the houri and argues that the houri is an ambiguous reward of paradise that has developed multiple meanings. At the most basic level, the houri is a companion, and the chapter elucidates the concepts of companionship and labor in the afterworld by comparing the houri to male companions in paradise. The houri is also a pure companion, and the chapter surveys explicit and implicit Qur ʾanic verses and Qur ʾanic commentaries that grappled with the houri’s meaning and her

relationship to purity and earthly wives. In eschatological literature, the houri becomes a more sensual reward for individual believers. This sense of individual reward is highlighted in manuals about jihad, where marriage to the houris is discussed. The chapter also assesses the houri as entertainment, and demonstrates that the houri provided inspiration for singing slave girls. These singing slave girls, in turn, may have influenced descriptions of houris who became known for their melodious voices. Since the chapter focuses on the developing tradition of the houri, it treats mainly Sunni texts and does not explore fully traditions of paradise and the houri that may be found in Shi ʿi and even Bahai texts.

Chapter 5, “The Promise,” explores websites and new media that use the houri. The chapter looks both to reformist Sunni websites where tours of paradise are presented as a form of education and also to jihadi videos that aim to develop affective bonds in recruiting in online communities. The chapter focuses on the videos of Anwar al-Awlaqi, the leader of al-Qa ʿida in the Arabian Peninsula, who used the houri to represent the wonders of paradise and to recognize the injustices of this world and the superlative nature of the cosmic world.

Chapter 6, “The Question,” brings together American and European perspectives and also classical Islamic and contemporary Muslim perspectives, presenting answers to a critical question in online communities about the houri: “If men receive houris, then what do women receive?” After assessing the assumptions built into the question, the chapter presents four different answers: Muslim women receive misogyny; they receive eternity with their husbands; they obtain higher status than the houris; or they receive male

houris of their own. The chapter concludes by suggesting that the question is evidence of an Islamic scriptural tradition in the twenty-first century that fuses American, European, and classical Islamic interpretations of the houri.

TERMS AND DATES

The houri is identified by different terms. Variations for houri in the singular and the plural can be found in Arabic and Persian. These include the plural terms hur ʿin in the Qur ʾan and hur al- ʿin (with the definite article “al”) in Islamic theological texts. They also include the singular ahwar and hawra ʾ, which do not appear in the Qur ʾan and only sometimes in theological texts. I generally use the term “houri” for the singular and “houris” for the plural since they have been English words since the eighteenth century. I highlight specific variations in the text, such as hora, horhin, hur, hur ʿin, hur al- ʿin, and al-hur al- ʿin, when their appearance is significant. Additionally, I have reflected the varied English orthography of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The book argues that the houri can be seen both as a being and an object. In the former case, the houri is identified within the context of companionship and marriage and is seen as an active character. The latter recognizes the houri’s physical composition as one of the rewards in the landscape of paradise and sees her as an inactive object. Reducing the houri to one or the other misses the multiple dimensions of the houri’s constitution in paradise.

The book follows the International Journal of Middle East Studies transliteration guidelines; however, all letters are not transliterated fully with diacritical marks. The Arabic

letter of ʿayn is expressed by ʿ and hazma is expressed by ʾ . Arabic proper names of twentieth- and twenty-first-century individuals either adopt their preferred spelling or commonly accepted English spelling. Finally, the book uses the Gregorian calendar for all dates. This usage signals an important reality. While the houri began as an Islamic figure, the amplified significance of the houri is due to American and European interpretations of her meaning.

THE LETTER

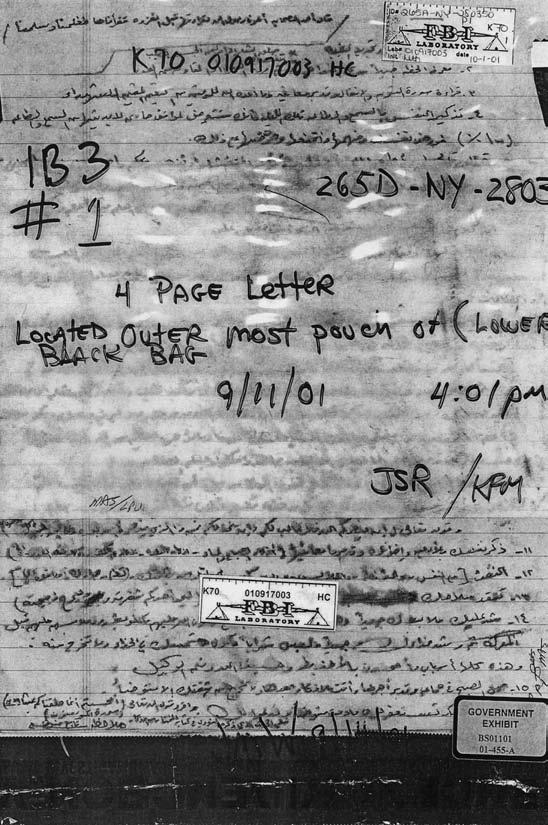

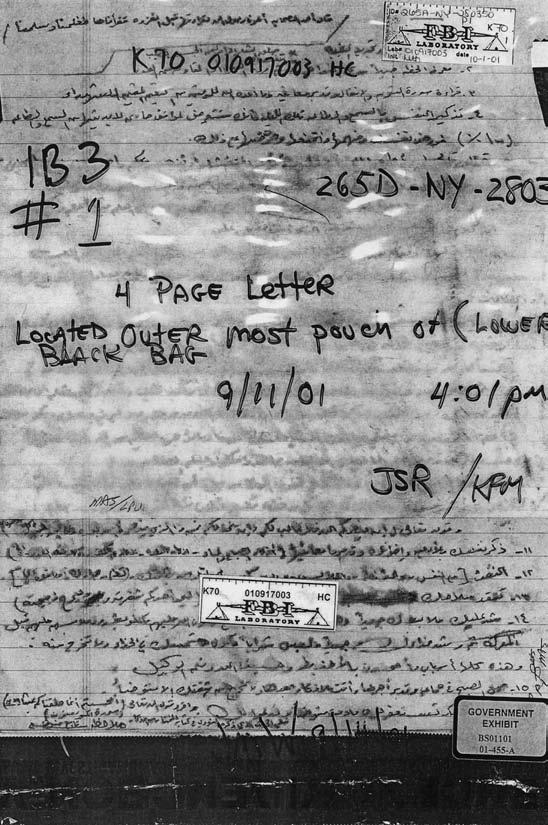

AFTER MOHAMED ATTA FULFILLED HIS mission by flying American Airlines Flight 11 into the North Tower of the World Trade Center, agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation found a handwritten Arabic letter in his luggage, left behind at Logan Airport. The bag had not been transferred to his flight to Los Angeles because his earlier Colgan Air flight from Maine had been delayed. He made it onto American Airlines Flight 11, but one of his bags missed the cutoff by two or three minutes. The FBI catalogued the letter as evidence on September 11, 2001, at 4:01 p.m.: “4 page letter. Located outer most pouch of (lower) black bag.”

The FBI found two other copies of the letter. One was discovered in the wreckage of United Airlines Flight 93 in Shanksville, Pennsylvania. Another was found in a car registered to Nawaf al-Hazmi and previously owned by Khalid alMihdhar, both part of the team that flew American Airlines Flight 77 into the Pentagon. These three letters provided proof that the hijacked planes were part of an organized, unified mission. On September 28, 2001, the Justice Department posted the letter on its website. The Justice Department had been criticized for the way in which it had translated the letter, so it released the original and let other organizations translate the text for the reading public. ABC News posted a

partial translation on the same day. The New York Times commissioned Capital Communications Group, a Washingtonbased international consulting firm, to provide a translation. By September 30, it was published in a number of Englishlanguage periodicals, and it is the translation that has been most widely circulated.1

Five years later, Zacarias Moussaoui became the first person to be charged for the September 11th attacks. During the trial, previously classified data were released. On March 4, 2006, he was sentenced to life in prison without parole. After the trial was completed, the prosecutors posted all 1,202 exhibits presented as evidence at the trial. One of the exhibits was the letter. Identified as “Prosecution Trial Exhibit BS01101,” the letter was accompanied by another translation (Figure 1.1).2

The letter had been called “Mohamed Atta’s letter” or “The Doomsday Letter” or “The Last Night” or “The Spiritual Manual,” but we do not know who wrote it. Since the Justice Department has not released all three letters, we cannot compare them. The letter can be found at the National September 11th Museum in New York City and on the Internet. For some people, it seems incredible that Mohamed Atta wrote a letter that detailed the steps of the mission, articulated its rationale, and then left it to be found in a piece of luggage. Others are suspicious because the FBI released only four pages, while Bob Woodward of The Washington Post had reported that there were five pages. In an article published on September 28, 2001, one of ten that helped The Washington Post win the Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting in 2002, Woodward described a fifth page that was written on standard stenographer paper with the heading “When you enter the plane.” The page also

Figure 1.1 Four-page handwritten letter in Arabic found in luggage recovered at Logan Airport, Boston, Massachusetts. Exhibit No. BS 01101 in the trial of United States of America v. Zacarias Moussaoui.

included a series of prayers or exhortations and some doodling that looked like a key.3 There continues to be confusion about the length of the letter. Most reports follow the FBI and refer to four pages. A few others cite Bob Woodward’s mention of five pages and suggest that the FBI may not have been transparent about all three letters.

The letter raises many questions. How were the copies made? How were they distributed? Did every hijacker receive one? Did Atta even write the letter? Or was it fabricated, as the conspiracy theorists suggest? In The 9/11 Handbook, Hans Kippenberg reports that one of the masterminds of the attacks, Ramzi Binalshibh, claimed that the letter was written by hijacker Abdulaziz al-Omari, who was part of Mohamed Atta’s team.4 We cannot answer all the questions that the letter raises. What is clear, though, is that the letter offers guidance to the hijackers, procedures for preparing for the attacks, and advice on how to renew their commitment to the mission. It is an odd document that draws on ritual piety, religious exhortation, historical references, and mental conditioning, all the while detailing an intended act of martyrdom whose violent aim was blunt.

This chapter tells the story of American reactions to the letter and how, in the wake of September 11, Americans have used the letter to understand the motivations of the hijackers and the religion of Islam. Americans used the letter’s promise of virgins of paradise to signal their revulsion at the hijackers. This in turn gave rise to an obscure, yet popular theory that the houris were really “white grapes” and not feminine companions at all. The hijackers would not receive the sexual reward that was assumed to be part of their motivation for the attacks. Since the emergence of the white grape theory, the houri has become a stock joke. The reactions to the letter