The American War in Afghanistan A His

CARTER MALKASIAN

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Malkasian, Carter, 1975– author.

Title: The American war in Afghanistan: A History / Carter Malkasian. Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Identifiers: LCCN 2020056939 (print) | LCCN 2020056940 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197550779 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197550793 (epub) | ISBN 9780197550809

Subjects: LCSH: Afghan War, 2001—United States. | Afghan War, 2001–Classification: LCC DS 371.412 .M327 2021 (print) | LCC DS 371.412 (ebook) | DDC 958.104/7373—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020056939

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020056940

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197550779.001.0001

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ListofMaps

ListofFigures

1. Thinking about America’s War in Afghanistan

2. The Country and Peoples of Afghanistan

3. The Taliban Emirate

4. The United States Enters Afghanistan

5. The Karzai Regime

6. Disorder in Kandahar

7. The 2006 Taliban Offensive

8. Taliban Rule, 2007–2010

9. War in the East

10. Taliban Advances

11. The Obama Administration and the Decision to Surge

12. The Surge in Helmand

13. The Surge in Kandahar

14. End of the Surge

15. Ghazni and the Andar Awakening

16. Intervention and Identity

17. The 2014 Elections

18. The Taliban Offensives of 2015 and 2016

19. The Trump Administration

20. Peace Talks

21. Looking Back

Notes

GlossaryandAbbreviations

Bibliography Index

LIST OF MAPS

Map 1. Map 2. Map 3. Map 4. Map 5. Map 6. Map 7. Map 8. Map 9. Map

10. Map

11. Map

12. Map

13. Map

14. Map

15. Map

16. Map

17. Map

18. Map

19. Map

20.

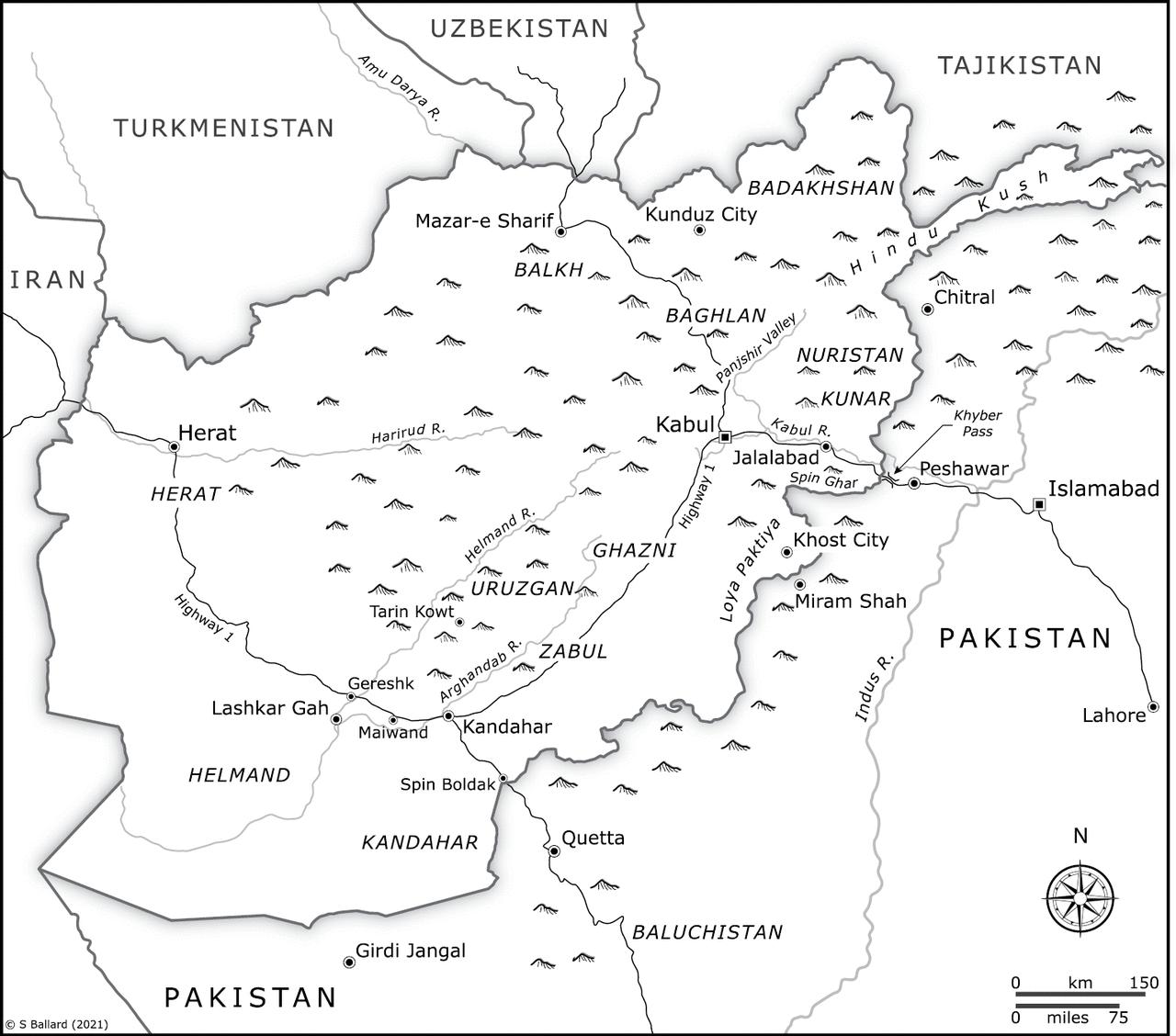

Afghanistan

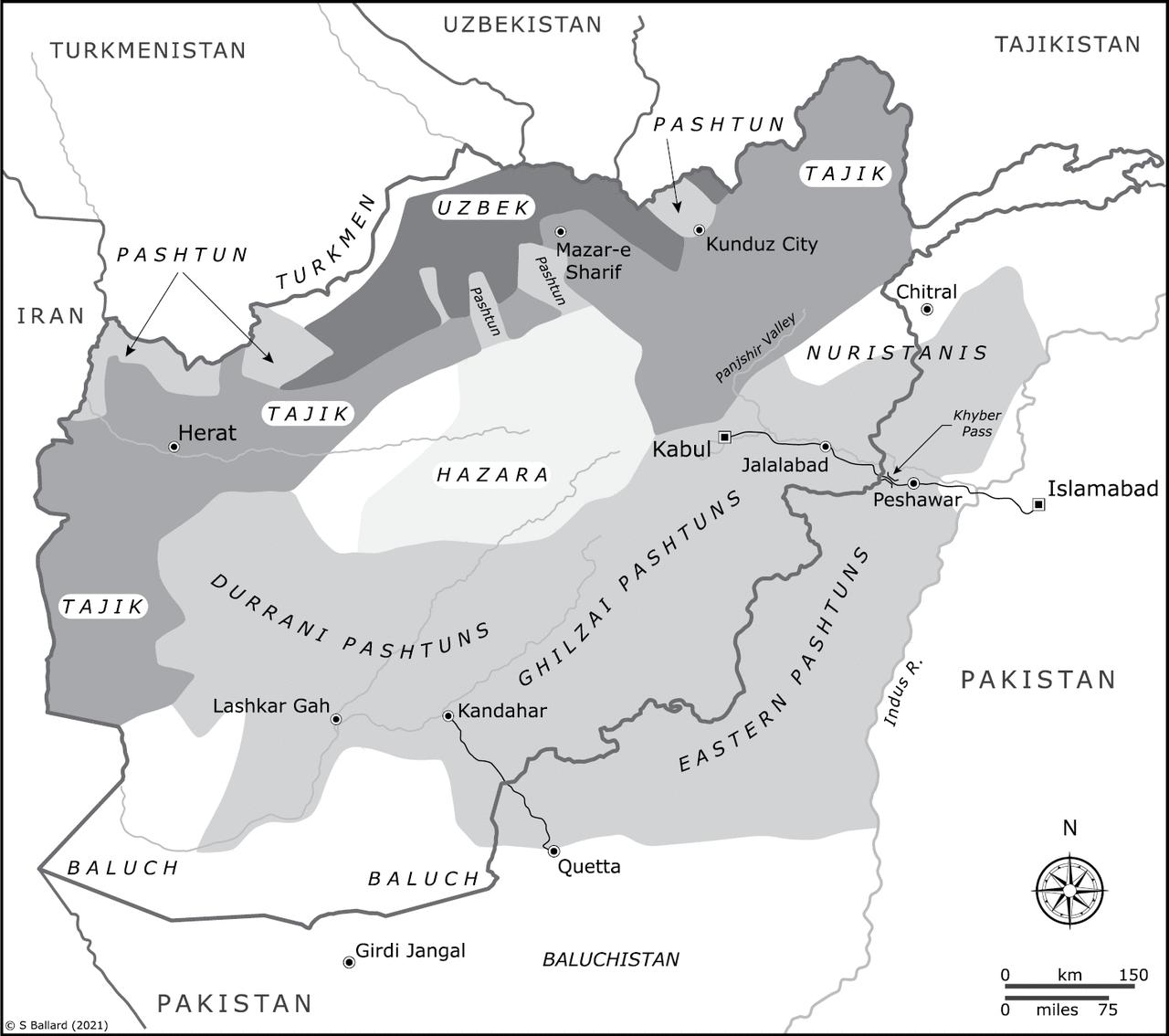

Tribes and ethnic groups of Afghanistan

Pakistan and the Afghan border

Kandahar

US invasion of Afghanistan

Tribes of Kandahar

Helmand

Sangin Bazaar and district center

Operation Medusa

Eastern Afghanistan

Kunar and Nuristan

Korengal Valley

Taliban territory, 2009

Marjah

Arghandab, Zharey, and Panjwai

Taliban territory, 2012

Ghazni

Sangin

Kunduz

Taliban offensives in central Helmand

Figure 2. Figure 1.

LIST OF FIGURES

Attacks in Arghandab, 2009–2012

Taliban control versus government control, 2007–2013

Thinking about America’s War in Afghanistan

The heart of Afghanistan was the countryside, the atraf. There in small villages of mud-walled homes, surrounded by fields of wheat, corn, or poppy, most Afghans lived. Bearded men with worn hands worked the fields. Barefoot boys and girls played on dirt paths. Women toiled unseen within the walls, bounded in shroud. Every village had a simple, singleroom mosque where men gathered to pray. Other than cell phones, cars, and assault rifles, the 21st century was invisible.

From 2001 to 2021, Americans passed through the countryside and its villages. Patrolling in green or tan camouflage, loaded with body armor, a helmet, ammunition, and water, with an M-4 or M-16 assault rifle or maybe a beltfed machine gun cradled in their arms, they wound their way through fields and around the villages. Sometimes they staked a post out of brown dirt-filled HESCO barriers and squatted for a year or two. Sometimes with glowing green night vision they burst in during the small hours on a raid, and then disappeared. And sometimes rifles hammered, explosions cracked, and a brother was carried away. Jangpeh atrafkaydie, say the Afghans. “War is in the countryside.”

On the outskirts of any village were mounds of gray rocks. They rested on a barren patch, or on high ground overlooking the fields, or shaded amid pine trees, or honored by a rickety wooden fence. A flag—a strip of cloth tied to a long bamboo pole—was planted in each. From afar, the whole plot was a fluttering multi-colored mass. It was the graveyard. For 40 years the graveyards grew. The tale of loss

could be heard in Hamid Karzai’s deep flowing Pashto when he sat face to face with the Taliban in 2019:

You have all seen, since three, four, five, six years, nay longer, that upon our dear soil across Afghanistan . . . from Kunduz, to Khost, to Herat, to Badakhshan, to Faryab, to the environs of Kabul, that . . . two graves lie side by side—dwa kabiratsang pehtsang prot dee. On one is a black, red, and green flag. On the other is a white flag. One in the name of the Taliban entrusted to the soil. The other in the name of the Afghanistan askar or soldier Around the graveyard, the graves of innocent Afghans are in great number, every mother’s heartfelt longing underground, every father’s pride buried.1

Americans and Afghans fought in Afghanistan, against each other and side by side, for more than 19 years. It was America’s longest war. Through 2021, it crossed four presidents—George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump, Joseph Biden. Fifteen US generals commanded there. Hundreds of thousands of US troops and diplomats were deployed. Thousands were killed or wounded. For a time it was “the good war.” In the wake of the attacks of September 11, Americans thought intervention just. In its latter years the war ceased to be good. It became only long and futile.

I decided to write a book about the whole Afghan War in 2013 after reading William Dalrymple’s majestic Return ofa King: The Battle for Afghanistan, about Britain’s first catastrophic foray into Afghanistan. His storytelling, thick with Dari poems and Afghan viewpoints, captured my admiration. Though I knew I could never match his skill, I wanted to follow his example and write a full history of America’s war in Afghanistan. Such a history, that drew on wide-ranging sources, had yet to be written.2

I had just become the political advisor to General Joseph Dunford, the commander of US and allied forces for all Afghanistan. I had already spent several months in Kunar province and nearly two years in Garmser, Helmand province, where I learned Pashto. I had written a book on the latter, War Comes to Garmser: Thirty Years of War on the

AfghanFrontier. General Dunford asked me to talk to Afghan leaders and visit the various regions to understand the local situation. The new job would allow me to see much of Afghanistan and meet with Afghans from different backgrounds and allegiances. I had that job until the end of August 2014 when General Dunford returned to the United States. A book on the whole war seemed possible from this vista.

My problem was that the war did not end. In fact, I was actually witnessing the beginning of a whole new phase. After 2014, I remained with General Dunford as he became chairman of the joint chiefs of staff, senior officer for the entire US Armed Forces. Serving as his advisor, I saw the war from an even higher viewpoint. I continued to visit Afghanistan regularly. In 2018 and 2019, I found myself spending months helping General Scott Miller, commander of US forces, in Afghanistan, and participating in peace talks in Qatar with Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad, US special envoy for peace talks with the Taliban. The war escalated and evolved—yet did not end. For years, I thought waiting for the end was going to turn out to be unrealistic. Then, on April 14, 2021, President Joseph Biden declared the final US military withdrawal would be completed by September 11 of that year. That denouement is still fresh, too close for reasonable perspective. But the events leading up to it can be understood and reflected upon. In that sense, the book ended up being a full history of America’s Afghan War from 2001 to 2021.

The Afghan War has a rich literature. Sarah Chayes’s The PunishmentofVirtue, published in 2006, is the best account of life in the first years of US intervention, inspiring because she lived in the middle of Kandahar and learned to speak Pashto. Over the following years, a library’s worth of books hit the streets. Reporter Sebastian Junger’s War about the Korengal Valley stands out among many good accounts of the experiences of Americans in combat; it is a vivid telling

of the experiences of a single platoon in some of the worst fighting of the war. The best book by a high-ranking official is Stanley McChrystal’s memoir, MyShareoftheTask, because it takes the reader straight into the misperceptions and contradictions of America’s 2009–2011 surge, when nearly 100,000 US troops deployed to Afghanistan. Rajiv Chandrasekaran’s LittleAmerica is a full treatment of those years. For a window into the Afghan people, Anand Gopal’s NoGoodMenamongtheLivingdescribes the hard lives of a warlord, a woman, and a Taliban. Then there are little-known gems such as Bette Dam’s A Man and a Motorcycle: How Hamid KarzaiCame to Power and David Edwards’s Caravan of Martyrs: Sacrifice and Suicide Bombing in Afghanistan. Steve Coll’s tome, Directorate S: The C.I.A. and America’s SecretWars inAfghanistan andPakistan, is an authoritative text on what happened behind closed doors in the halls of power and is essential reading for the details of Pakistani policy and US peace efforts.

This book synthesizes earlier works into a single history while incorporating my own new research. The time in Kunar and Helmand and the 17 months with General Dunford and various visits since are sources of discussions, interviews, and firsthand observation of events. I have been to 15 provinces, with the most time spent in Helmand and Kunar, and Kandahar as a distant third. I have thoroughly reviewed Pashto written sources, including newspapers, books, and magazines. Friends have gone to Pakistan to bring me Taliban histories, documents, propaganda, and poems. I have mined key Pashto texts written by Taliban, hitherto unreferenced by Western scholars. These include the biography of Mullah Omar by his former spokesman, Abdul Hai Mutmain; the memoir of former Taliban foreign minister, Wakil Ahmed Mutawakil; and the history of the Taliban movement by Abdul Salam Zaeef, former ambassador to Pakistan and one of the most respected figures in Afghanistan. Additionally, I have conducted indirect surveys

in which contacts interviewed dozens of Taliban fighters and commanders. And I have spoken directly to Taliban in Doha, in Kabul, and in the provinces.

The Afghan War’s meanings for America have been subtle. It was not the all-encompassing experience of the Second World War or the American Civil War. Nor was it the searing national trauma of Vietnam. And it was not the shame of Iraq. The Afghan War’s most direct impact was checking the terrorist threat to the United States. Afghanistan was the first front in the “war” on terrorism. Intervention prevented further harm to Americans. The war also changed the US military. Counterinsurgency, counterterrorism, special operations forces, and drone strikes are examples of new concepts, organizations, and tactics that emerged. Civilmilitary relations were tested in a way unseen since the Cold War. The war’s meaning deepens when it comes to US foreign policy. It contributed to the Bush-era rush to fight terrorism and then later to the backlash against intervention that spawned the isolationism of the Trump years. There were macroeconomic implications as well. The war’s formidable cost diverted funds from America’s economic development at a time of slowdown. Above all, the Afghan War, along with Iraq, was the combat experience of a generation of US servicemen and women. For that reason alone, it matters.

The war’s meaning was far greater for Afghanistan. It was the longest phase of a 40-year civil war that shook all walks of life, revolutionized politics and society, and reshaped culture. America’s Afghan War was the second half of that civil war. Hundreds of thousands more Afghans died, millions fled their homes. From GPS-guided bombs to the cancer of suicide bombing, the Afghan people confronted new horrors. Over its long course, the war widened Afghanistan’s divisions, between city and countryside, between Pashtuns and Dari-speakers, between haves and have-nots. Some

good occurred, for infrastructure, education, freedom of the press, and women’s rights; in a few lucky places, US soldiers, marines, and diplomats safeguarded years of tranquility. Democracy took root, sprouting elections and representation. At the same time Taliban Islamic rule entrenched itself. Worst of all, the war twisted the Afghan people. Extremism spread. The Islamic State appeared. Sacrifice, suicide, revenge, and killing ascended as values. Violence begat violence. In December 2001, Afghanistan’s two decades of civil war appeared to be a passing nightmare. In December 2019, at the four-decade anniversary, violent disorder appeared to define a long-term reality.

The question of why we lost looms large. Or put another way for any who reject the verdict, why did the United States not prevail between 2001 and 2021? Although the al-Qa‘eda leader Osama bin Laden was killed and no major attack on the American homeland was carried out by a terrorist organization based in Afghanistan after 2001, the United States was unable to end the violence or hand the war to the Afghan authorities, which could not survive without US military backing. My goal when I started writing was to explain how the Afghan War came to a disappointing resolution, one that subjected the Afghan people to years of destruction. I especially wanted to highlight key mistakes and better paths that might have been taken.

I was already taken by several explanations for the direction of the war. The writings of Sarah Chayes, among others, founded a compelling argument that Afghanistan was suffering from unremitting violence because the government mistreated the Afghan people and Pakistan undermined peace. I sympathize with this argument. My own experiences also convince me that the tribalism underlying Afghan politics and society was so divisive that it encouraged instability.

A feeling that something more was going on nagged me as I left Afghanistan in August 2014. The United States had been in Afghanistan since 2001 and the country was still in trouble. Afghanistan’s government by then had far more soldiers and equipment than the Taliban. Yet its forces were losing on the battlefield. The existing explanations helped but could not fully explain what I was seeing. Could I really lay what was military ineffectiveness on government mistreatment of the people or Pakistan? The logic felt forced. What do mistreatment and Pakistan have to do with the fact the government had the military tools to defend itself but was consistently losing to inferior numbers of Taliban? Tribal and political infighting offered a more compelling explanation but I could not tie it to every major case of battlefield defeat. All of these clearly were necessary conditions for what has transpired but their sum amounted to something less than the hardship that was playing out before my eyes.

In October 2014, I attended a small, closed-group discussion at the State Department with Michael McKinley, who had recently been appointed US ambassador to Afghanistan. We were having a lively debate on why the Taliban fight when the ambassador interjected, “Maybe I have read too much Hannah Arendt but I do not think this is about money or jobs. The Taliban are fighting for something larger.” Ambassador McKinley’s words captured what I was feeling but had not articulated.

The Taliban exemplified something that inspired, something that made them powerful in battle, something closely tied to what it meant to be Afghan. In simple terms, they fought for Islam and resistance to occupation, values enshrined in Afghan identity. Aligned with foreign occupiers, the government mustered no similar inspiration. It could not get its supporters, even if they outnumbered the Taliban, to go to the same lengths. Its claim to Islam was fraught. The very presence of Americans in Afghanistan trod on what it

meant to be Afghan. It prodded at men and women to defend their honor, their religion, and their home. It dared young men to fight. It animated the Taliban. It sapped the will of Afghan soldiers and police. When they clashed, Taliban were more willing to kill and be killed than soldiers and police, or at least a good number of them. To the extent that this book has an overarching argument, it is that the Taliban’s tie to what it meant to be Afghan was necessary to America’s defeat in Afghanistan.

The literature to date has respectfully neglected this explanation. Although there are studies of Islam in Afghanistan, the possibility that Islam and resistance to occupation played a role in America’s Afghan War has gone oddly unnoticed, almost shunned—in a country where people have eagerly tried to convert me to Islam, where religion defines daily life, and where insults to Islam instigate riots. The largest popular upheaval I witnessed in Afghanistan was not over the government’s mistreatment of the people or Pakistani perfidy. It was over the possibility that an American had damaged a Koran. Thomas Barfield, a leading scholar on Afghanistan, best describes religion in Afghanistan: “There is no relationship, whether political, economic, or social, that is not validated by religion. . . . it is impossible to separate religion from politics because the two are so closely intertwined.”3

The book that comes nearest to this explanation and has indeed influenced me is David Edwards’s CaravanofMartyrs: Sacrifice and Suicide Bombing in Afghanistan. His thoughtprovoking work details how the act of martyrdom radicalized the war and war radicalized martyrdom. Edwards’s most striking explanation for why suicide bombing became embedded in Afghan society, one that drives right to the heart of those of us who served in Afghanistan, is US occupation. Just as an Afghan tribesman was obligated to defend his family and land, so too was he obligated to do everything in his power to defend the Afghan homeland and

seek revenge when that was not possible. A man who did otherwise was nothing. Prolonged US occupation tore at this obligation. Night raids, searches, ubiquitous armored convoys, mixing of men and women, and general ignorance of Afghan honor inflamed the humiliation. For Edwards, drones were the most pernicious. There was no defense against their distant strikes. The only recourse was revenge. Not all Afghans were driven to act. But enough were: “Some find that the way they can recover their honor and identity is by killing themselves in the process of killing those who have defiled their honor. . . . The bomber reclaims lost honor and standing in the community, he does his duty (farz ‘ain) according to Islam (as interpreted by Taliban clerics), and he performs the political act of striking an unjust oppressor.”4

The explanation of Islam and resistance to foreign occupation is powerful because it answers questions that arguments about grievances or Pakistan cannot. It is not the singular sufficient condition for the outcome of the Afghan War. It is a necessary one. Its impact is resounding: any Afghan government, however good and however democratic, was going to be imperiled as long as it was aligned with the United States. In turn, the United States was drawn to stay longer and longer: civil war in perpetual motion.

The explanation is also dangerous. It can be misinterpreted as meaning that all Muslims are bent on war or, worse, are fanatics. Such an interpretation would be wrong. Islam was a source of unity, justice, and inspiration. It was not the source of terrorism or atrocity. Although a few were extremists, unlike al-Qa‘eda, the Taliban as a whole were not and had no intention of plotting terrorist attacks on foreign countries. The point is that it is tougher to risk life for country when fighting alongside what some would call occupiers, especially when they believe in a different religion. To say that a people have sympathy for their countrymen and co-religionists over foreigners is hardly to label Islam a root of evil. Many people in many countries behave the same when faced with foreign

intervention. As Samuel Huntington reminds us, “The principal impetus to . . . [revolutionary] movement is foreign war and foreign intervention. Nationalism is the cement of the revolutionary alliance and the engine of the revolutionary movement.”5

The argument builds upon my earlier book on Afghanistan, WarComestoGarmser. In that book, I concluded that better decisions on the part of the United States would have led to a better outcome in Garmser. I thought we should have done more early on to build a stronger military, remove bad leaders, and manage tribal infighting. Evidence suggests that such actions may have led to greater stability, though the intervening years have left me more cynical. I have seen how hard it is to enact decisive new policies on a nationwide scale.

Like that book, this one too asks whether better decisions could have brought a better outcome, though it looks at the whole war instead of a single district. Themes of mistreatment, Pakistan, tribalism, and Islam and occupation run throughout. They set the war on a windy and rocky course. Was there anything the United States could have done to chart a calmer course? Could it have defeated its adversaries? Could it have fought a less costly war?

Throughout the war, journalists, academics, experts, and officials fielded a host of criticisms: the Bush administration distracted itself with Iraq; US air strikes and night raids enraged the Afghan people; the Obama administration put a deadline on the surge; all three administrations permitted widespread government corruption. Were these really mistakes? Did they matter? Were there other mistakes?

When it comes to what could have been done differently, I suspect the biggest question for most Americans is: Why didn’t we just leave? “The failure of American leaders— civilians and generals through three administrations, from the Pentagon to the State Department to Congress and the

White House—to develop and pursue a strategy to end the war ought to be studied for generations,” wrote the NewYork Times editorial board in 2019.6 I have met few Americans who disagree that after September 11 we were right to go in, hunt down al-Qa‘eda, and overthrow the Taliban. To the end of 2019, Gallup and other credible public opinion polls find that a majority of Americans never believed that the US decision to invade Afghanistan was a mistake.7 Yet, in my anecdotal experience, most Americans also assume we should have left some time after that. I have often been told that we were sacrificing American lives and treasure for very little. Over time, the terrorist threat, palpable at the outset of the war, became less tangible as al-Qa‘eda was pounded into the ground. The book will try to offer insight into why the United States did not withdraw until 2021 and instead committed to a faraway war in support of a fragile government; how, as the attacks of September 11 drifted farther and farther away, president after president decided to stick it out in a poor, landlocked country in the middle of Asia.

For the United States, Afghanistan was a long war but also an experience. It feels wrong to cast the entire experience as bad or evil. Better, I think, to see the good as well as the bad. I would not want to forget the friendships Americans forged with thousands of Afghans who were honestly trying to improve their country: whether a hard-working farmer, an idealistic technocrat, a heroic commando, an overburdened policeman, or a pathbreaking young woman. And I especially would not want to forget the kindness US servicemen and women brought to many Afghan lives and their dedication to protecting Americans at home. For me, America’s Afghanistan experience is a dark, cloudy front with points of sunlight. The last thing I want to do is condemn it and all involved.

With that in mind, we must confront a moral reality. The United States may have done more harm than good. Afghanistan’s history since 1978 has been a story of trying to end civil war. The Taliban regime brought a few years of uneven respite before America’s arrival jump-started the trauma. The Taliban were far from good. They oppressed women, hollowed out education, and silenced free speech. Our intervention did noble work in these spheres. But that good may not balance out the violence, death, and injury. Without our intervention, Afghans would have been deprived and oppressed, but alive. We should stand back and ask: In the name of stopping terrorism for our own sake, did we liberate, or oppress, the Afghan people?

The book looks at the war from the end of 2001 to the beginning of 2020. After this first chapter, chapters 2 and 3 briefly cover Afghanistan’s culture and society, the SovietAfghan War, the ensuing civil war, and the first Taliban regime. The story really begins with the US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 and Karzai’s first years in power in chapters 4 and 5. The strategy of the Bush administration, the constitutional process and loya jirgas, and missed opportunities for peace talks with the Taliban are described in detail.

The next chapters (6, 7, and 8) explain how the Taliban reformed and instability returned, culminating in the Taliban offensive of 2006. Major battles in northern Helmand and western Kandahar comprise one of the most decisive events of the war. I also describe the Taliban movement under Mullah Omar and his lieutenants—Mullah Dadullah Lang and Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar. Chapters 9 and 10 discuss the hard fighting Americans, British, and Canadians then experienced from 2007 to 2009 in long campaigns in the mountains of Kunar and Nuristan, throughout Helmand, and around the city of Kandahar. The battles American soldiers

faced in the Korengal, Wanat, and other mountain outposts came to symbolize the war.

Then we turn to the surge of 2009 to 2011 in chapters 11 to 14. We examine Obama’s painstaking decision to surge, General Stanley McChrystal’s new counterinsurgency strategy, and the battles of Helmand and Kandahar—Marjah, Sangin, Arghandab, Panjwai, Zharey. This is the height of America’s military experience in Afghanistan. It ends with the dramatic change in US strategy to drawing down and passing the war to the Afghan government.

The latter third of the book details the fighting of 2014 onward, after America had drawn down and the Afghan government tried to face the Taliban on its own. Chapters 15 to 18 discuss the unity government deal of 2014, the transition of Taliban leadership from Mullah Omar to Akhtar Mohammed Mansour, the Taliban offensives against Kunduz, Helmand, and other provincial capitals in 2015 and 2016, and the travails of the Afghan army and police. The results of America’s efforts are truly evident here. Obama’s strategy once more had to change. The rise of the Islamic State and the Taliban under the new leadership of Maulawi Haybatullah is also discussed. The book concludes in chapters 19 to 21 with the new policies of US president Donald Trump, the peace talks of 2019–2020, and a final summary of why we failed, what opportunities existed for a better ending, and why America never just got out.

Out of necessity the book has to focus on certain topics and regions to the detriment of others. US policy, military operations, and the Afghan side of the war (military and civilian, local and national) receive extensive attention. Events in the east, Kabul, and the south are described in detail. That the book has a bias toward Helmand and Kandahar, epicenters of the war and my experiences, should come as no surprise. The north and west, unfortunately, are less well attended, other than during dramatic events. Since the focus is on war, the story of democratic progress,

institutional reforms, and international development assistance is presented only in broad brushstrokes. The same goes for the many advances experienced by the Afghan people. Kabul’s youth movements and civil society are largely excluded. I also try to present the Taliban story. Pakistan is too important to be excluded but I withhold from delving into details of their internal politics or military operations. US allies and the coalition get the shortest shrift. Fifty-one countries joined the international military mission in Afghanistan at one point or another. They go unseen for long stretches. I habitually discuss US strategy in isolation. Afghanistan is ripe for a proper international history. A foreigner in Afghanistan always has more to learn. On culture. On tradition. On families. On women. We never fully broke through the curtains segregating Afghans. The longer I study Afghanistan, the less I realize I know.

Writing this book has swallowed years. I am indebted to many. Derek Varble, historian and colleague at Oxford, rendered invaluable service commenting on the full manuscript. Thanks also go to Chris Kolenda, Matt Sherman, Dale Andrade, Daniel Marston, and Jerry Meyerle for graciously reviewing various chapters. Discussions with Stephen Biddle, Roger Myerson, John Nagl, David Edwards, Bruce Hoffman, Zach Constantino, Alison Kaufman, Robert Powell, Neill Joeck, and Tom Barfield were hugely beneficial. Teaching a yearly course on Afghanistan to dozens of insightful graduate students for Eliot Cohen at the School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University, endlessly refined my ideas and conclusions. The think tank CNA and Bob Murray, Katherine McGrady, and Mark Geis were generous in allowing me the time to complete a book outside work (and that represents my own thoughts, not that of any organization). My final thanks go to David McBride, Emily MacKenzie, Cheryl Merritt, Elizabeth Bortka, and the

team at Oxford University Press who once more patiently guided me through the writing of a book.

Map 1 Afghanistan

The Country and Peoples of Afghanistan

Afghanistan is a hard country, a land of desolate mountains and deserts, on the edge of the Middle East and South Asia, locked between Iran, Russia, and Pakistan. The towering Hindu Kush mountains break from the Himalayas and form a great massif across the center of the country. Rivers drain out of the Hindu Kush: the Kabul and Kunar in the east, the Amu Darya in the north, the Harirud in the west, and the Arghandab and Helmand in the south. They water valleys of farmland, widest around Jalalabad and Kandahar, in most other places less than a three-hour walk from either bank. Tributaries with thinner wisps of adjoining farmland feed the main rivers. Outside the mountains and fertile rivers lie deserts. The largest are in southern and western Afghanistan, stretching to Pakistan and Iran.

Afghanistan’s population has risen over the years from roughly 12 million during most of the 20th century to 33 million in 2020, with the majority, 70 to 80 percent, living in the countryside.1 The city of Kabul, nestled in a divide in the Hindu Kush, has been the seat of power for two centuries. At nearly 6,000 feet, for many the temperate climate is preferable to the summertime heat of Afghanistan’s other cities.

Afghanistan is divided into provinces, 34 in 2020, each subdivided into five to fifteen districts. As Professor Thomas Barfield, don of Afghan studies, points out, it is easier to think in terms of four regions that circle Kabul. Moving clockwise, we can start with the north, where mountains and valleys descend to farmland along the Amu Darya. Mazar-eSharif, home of the Blue Mosque, a shrine to Ali, is the

north’s biggest city. Moving on, we go to the east, a land of high mountains and the Pakistan border. Its largest city is tree-lined Jalalabad, sited amid lush green farmland astride the Kabul River that flows into Pakistan. Next is the south, flatter and drier than any other region. Vast deserts blur the border with Pakistan. The ancient city of Kandahar is the south’s capital, where Afghanistan was founded. Only Kabul surpasses its political weight. The last region is the west, bordering Iran’s deserts. The city of Herat is a famous center of poetry and learning. Its people, sometimes called roshan fikrai, or “bright thinkers,” are known for their education. In every region, a few smaller cities—probably better described as towns—exist as well, mostly at the center of bigger or more populous provinces, such as Khost city (eastern Afghanistan), Kunduz city (northern Afghanistan), and Lashkar Gah (southern Afghanistan).

Map 2 Tribes and ethnic groups of Afghanistan

Afghanistan has several ethnic groups. The Pashtuns are the biggest at about 40 percent of the population, roughly 13 million people at the beginning of the 21st century.2 Pashtuns have traditionally ruled Afghanistan. Some elements of Afghan identity have been Pashtun characteristics that have been laid over the entire country. Pashtuns live primarily in the east and south, with substantial pockets in the north and west. A larger Pashtun population exists across the border in Pakistan, partitioned by the 1893 Durand Line. Pashtuns speak Pashto, one of