PREFACE

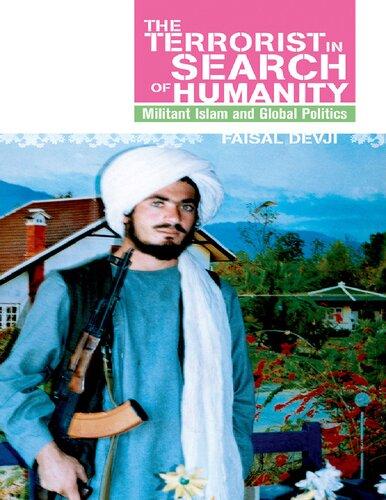

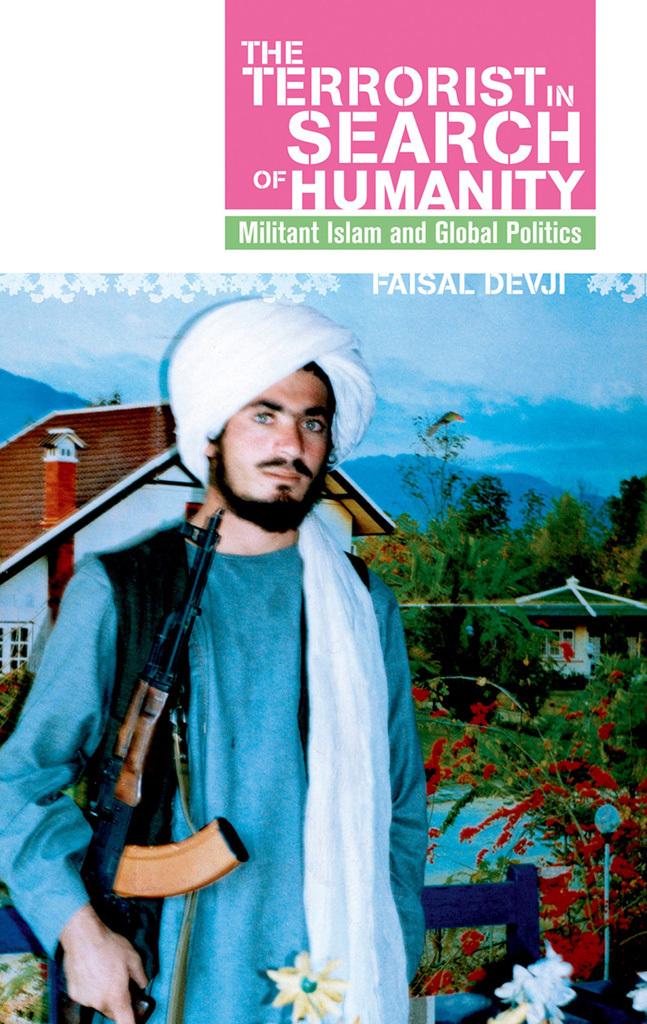

Though it was an illegal practice under the Taliban, photographs continued to be taken in secret studios across Afghanistan during their rule. With the country’s invasion by coalition forces following the 9/11 attacks, many of these studios and their rolls of negatives came to light, courtesy of an enterprising German photojournalist who published the previously illicit images of ordinary Afghans and even Taliban fighters posing against elaborate backdrops.1 Dressed in street clothes and equipped with guns of various sorts, men and boys are depicted in such photographs standing or sitting before Swiss chalets and other pastoral settings, both European and Asian, with bunches of plastic flowers making up the rest of the décor. One such image appears on the cover of this book. However criminal they might have been, these portraits are not in the least idiosyncratic, illustrating despite their display of firearms a set of standard poses and generic backgrounds familiar across wide swathes of South and Central Asia. Indeed the Alpine scenes so popular among the Taliban’s subjects are sold in glossy and outsize formats on the streets of African and Asian cities, their originals having been filmed as settings for many a Bollywood romp.

So common are these pastoral scenes that they form a significant part of militant imagery as well, especially on video and websites commemorating suicide bombers and other martyrs, whose portraits are frequently set amidst verdant landscapes and surrounded by flowers.2 Such depictions no doubt invoke traditional Muslim visions of paradise, but they are also examples of kitsch as a global form that belongs to no particular religion. There is an intimate relationship between the Taliban fighter photographed before a Swiss chalet and pictures, popular since the nineteenth century, of Jesus knocking at the door of a similar building. Interesting about all these images is the fact that none of their subjects belong to the

settings in which they seem to have strayed. Whether it is Jesus in a German village, Indian film stars on a Swiss mountainside or a Saudi martyr in a landscape with waterfalls, these figures are all set apart from their surroundings. While it might appear at first glance as if this merely reinforces the fantasmatic nature of such backdrops, a closer look reveals that exactly the opposite is true: it is everyday reality that these terrorists, martyrs and men about town seem detached from, with their clothes, guns and demeanour alienated from quotidian use in studied poses.3

For the most part such armed figures manage to avoid the actionhero mannerisms popularized by Hollywood, also departing the latter’s ideals of masculinity by their limpid expressions and sometimes androgynously painted or retouched faces. This is the ideal not only of the Afghan men photographed in clandestine studios, but also of Al-Qaeda’s martyrs, who are meant to be more beautiful in death than they ever were in life. If smiling lads point pistols at each other in these photographs, or militants appear on videotape firing semi-automatic weapons, this does little to alter the curious repose that marks such images. Many of the Taliban photographs, for instance, portray gunmen clasping hands or looking into the camera with hands over their hearts in poses of humble welcome. Yet this departure from Hollywood stereotypes by no means indicates the presence of some alternative aesthetic in the wilder reaches of the Hindu Kush, since such local histories of the Muslim imagination have become globalized in the form of kitsch, which now provides a powerful medium for the transmission of militant as well as pacific ideals. Of course not all of these ideals take the form of kitsch, though each moves horizontally, connecting people separated by history, geography and language through media in the way that fashion or advertising does, and not vertically by the kind of indoctrination that requires a hierarchically controlled environment to function.

Whatever the local context of militant practices, they possess a global form facilitated by the random connectivity of technology and spectacle, whose history passes through the printing presses,

studios and cinema sets of the last two centuries as much as it descends through the Quran and its commentaries. However ephemeral these connections, their consequences for militant behaviour are as significant as those of media and advertising upon consumer behaviour worldwide, itself by no means a trivial matter. Partisans of Al-Qaeda are mindful of the global form their practices take, and try hard to lend them planetary significance. But unlike communism or even fundamentalism in the past, this significance does not lie in the attempt to create an alternative model of political and economic life on a global scale, given that the moral virtues favoured by militants neither presume nor require a revolutionized society for their instantiation. Instead these men speak from within the world of their enemies and seem to possess no place outside it. Like the kitsch forms they often take, militant ideals subvert our political reality from the inside, if only by exceeding it with the violent lustre of their hyperreality. So despite the exotic appearance of its minions, it is only natural that Al-Qaeda should lack a utopia of its own.

If Osama bin Laden speaks so familiarly of his foes, it is because he employs the same categories as they do, in particular those of humanism, humanitarianism and human rights. By invoking such terms the men associated with Al-Qaeda signal their interest in the shared values and common destiny of mankind. Indeed militant rhetoric is full of clichés about the threats of nuclear apocalypse or environmental collapse posed by the arrogance and avarice of states and corporations that happen also to threaten Muslims around the world. Those who defend Muslims, then, automatically protect the common interests of the human race. Once the threat supposedly levelled at Muslims by the United States and its clients is defined in these familiar terms, militant rhetoric can no longer remain something traditional or foreign. In fact its global influence is based precisely on stereotypes that are shared across the planet. This book is about the globalization of militancy by way of such planetary ideals. It focuses on humanity as the ideal that permits terrorism to stake its claim to a global arena in the most powerful way.

1 Thomas Dworzak, Taliban (London: Trolley, 2003).

2 For a collection of these images see “The Islamic imagery project: visual motifs in jihadi Internet propaganda”, Combating Terrorism Center, Department of Social Sciences, United States Military Academy at West Point, March 2006 (http://www.ctc.usma.edu).

3 For discussions of the history and significance of this aesthetic, see Arjun Appadurai, “The colonial backdrop”, Afterimage, vol. 24, issue 5, March/April 1997, pp. 4-7, and Christopher Pinney, Camera Indica: The Social Life of Indian Photographs (London: Reaktion, 1997).

SLEEPING BEAUTY

Osama bin Laden and his lieutenant Ayman al-Zawahiri have repeatedly offered a truce to countries anywhere in the world that cease attacking Muslims, for instance by withdrawing from the coalitions engaged in the invasion and occupation of Afghanistan or Iraq. The proposed truce was first announced on 15 April 2004 by way of a video communiqué smuggled out of Afghanistan on an audiotape and later broadcast on the pan-Arab television stations AlJazeera and Al-Arabiyya:

So I present to them this peace proposal, which is essentially a commitment to cease operations against any state that pledges not to attack Muslims or interfere in their affairs, including the American conspiracy against the great Islamic world. This peace can be renewed at the end of a government’s term and at the beginning of a new one, with the consent of both sides. It will come into effect on the departure of its last soldier from our lands, and it is available for a period of three months from the day this statement is broadcast.1

On the one hand such a truce was rightly dismissed as media rhetoric in the West, largely because it had no institutional backing— Al-Qaeda’s leaders being inaccessible and possessing no party, army or state that might be negotiated with. After all the movement’s founders were themselves in hiding and incapable of exerting any control over the suicide bombers they inspired.2 But on the other hand by taking the trouble to reject Bin Laden’s offer formally, European governments lent his words a degree of credibility and even a kind of nameless reality, recognizing in this way that their politics could no longer be confined to its traditional forms and institutions. Since then calls by senior political and military figures in Europe to “negotiate” with Al-Qaeda have proliferated, alongside

furious denunciations of any such attempts at “appeasement”, and all this despite the fact that there is nothing and nobody to talk to— apart from a great many disconnected persons and a small number of media personalities.3

While it used the language of traditional politics, Al-Qaeda’s truce represented something quite new. Bereft of institutional features like negotiation, arbitration and contractual guarantees, it was a truce that had lost one kind of political meaning without having gained another, since trust was the only thing that either side had to offer. It was as if such everyday terms had come to serve as the bridge to a new, and yet unknown politics that took for its arena the globe in its entirety. Notwithstanding its dismissal by Western governments, the groundless trust upon which this truce was based achieved an ambiguous political reality in the public debate that followed AlQaeda’s offer, with Spain’s withdrawal of troops from Iraq after the Madrid bombings that year widely being seen as an acceptance of Bin Laden’s terms. Indeed Spaniards seemed to have accepted this truce even before it was offered when they elected an anti-war government three days after the blasts on 11 March 2004. While the new Spanish government, in other words, had reasons for withdrawing from Iraq that had nothing to do with Osama bin Laden’s truce, his videotape hijacked the politics of this European state by inserting it into another kind of global narrative.

But what kind of truce was this in which neither institutions nor discussions were involved—since Al-Qaeda’s political invisibility robbed even the Spanish state of its institutional character by appearing to force its withdrawal of troops from Iraq on the basis of trust alone? The extraordinary spectacle of a European state coerced into acting out of good faith by a terrorist on the run somewhere in the Hindu Kush was made possible by the global media, which did not simply represent or even influence politics but actually took its place. For in the absence of institutional forms like negotiations and guarantees, not even behind the proverbial scenes, publicity served as the only medium for Osama bin Laden’s truce, which it also guaranteed in a purely declarative way. In other words it

was precisely the authority of a warrior incapable of engaging in battle, and living in fear of his life, that gave his words credibility in the eyes of friends and enemies alike. Osama bin Laden’s peace proposal is important as an example of militancy trying to found a global politics outside inherited forms and institutions. For with the dispersal of its founders during the Anglo-American invasion of Afghanistan, Al-Qaeda has itself outgrown whatever institutional form it once possessed to become the trademark for a set of ideas and practices that are franchised by militants the world over.4

Having dispensed with the parties, armies and states of old for dispersed networks trademarked by the Al-Qaeda logo, our militants lack even an ideology. Indeed we shall see how their fighters jettison Islamic law itself as a political model to make an individual duty out of it, for however international their claims, ideologies have classically been focused on the nation state. Without the grounding provided by such a state, they begin to fragment, and one is left with lines of thinking rather than a system of thought. This precisely is the case of Al-Qaeda’s franchise, which has lost ideology to the degree that it has abandoned the nation state and with it Islamic law as a model, claiming territory only in the abstract terms of a global caliphate. By this I do not mean to downplay local or traditional forms of militancy, only to suggest that the global reach of militant networks associated with the brand name Al-Qaeda increasingly gives even such regional practices their radical meaning and mobility. So the authors of a report on Iraqi insurgent media point out that even the most localized and nationalist of militant outfits there, including those that set themselves against Al-Qaeda, take the sophisticated media products of such global jihad movements as their visual and rhetorical models. Given the parlous state of Iraq’s infrastructure, the collectively and sometimes transnationally produced websites or videos these outfits release are not even targeted at a domestic audience, which therefore gains access to them only by way of news media based outside the country.5

Local forms of Islamic militancy are therefore increasingly mediated by global conditions rather than the other way around, for

however traditional their aims, such militant practices end up losing their political meaning in a global arena that bestows on them an existential dimension in return. Thus a number of militant groups in Pakistan or Afghanistan appear to rely increasingly upon Al-Qaeda’s name and technique to achieve both their global reputations and connections, however local their aims and operations might in fact be.6 And it is exactly the existential dimension of such globalization that is deserving of scrutiny, because it signals the political fragmentation of militancy in a planetary arena whose lack of institutional forms ends up diverting its violence into the practices of everyday life, whether in the form of ordinary individuals plotting jihad online, or school friends concocting bombs in suburban basements. These disconnected and unrelated participants in Islam’s long-distance militancy do not simply serve as the sympathetic supplements of some short-range politics, but instead reach out beyond the latter’s calculations and transform its practices, constituting the local by the global in ways that no longer permit the former’s politicization in any traditional way.

The importance of a global arena to militancy is demonstrated by the fact that terrorist outfits of the most varied description, even those in places like Iraq that deal with explicitly local causes, very commonly describe themselves by using an Arabic word, alam, that has come to define the globe as opposed to the world or dunya, this latter still being linked to the old religious idea of worldliness and so aligned with politics as a profane activity while at the same time being juxtaposed to the afterlife.7 For the globe represents not worldliness but rather existence as such, including that of humanity as a whole, and so cannot be partitioned between friend and enemy, or the material and the spiritual, in any old fashioned way. The earth or ardh is similarly discarded in militant rhetoric, only appearing in some quotations deployed from the Quran, its reference as a ground for the action of human or divine subjects having been replaced sometimes by a vision of the globe as pure geometry and at other times by the planet as an object of conquest. In its sheer gigantism, therefore, the planet that militants describe appears to have

stretched beyond the language of politics as much as religion, so that the logos and emblems of jihadi groups frequently represent it as an abstract and completely foreign entity to be conquered and assimilated into the experience of Muslim life. Entirely typical instances of this are images of the globe planted with a flag bearing the Islamic credo or skewered by a scimitar like some monstrous kebab.

Unlike Muslim politics of a previous generation, the new militancy is concerned neither with national states nor with international ideologies, though like other global movements dedicated to the environment or peace it does not seek to overturn these, taking instead the globe and all who inhabit it for sites of action. This is perhaps why Al-Qaeda’s advocates often recast the geography of Islam, replacing political references like Iraq or Afghanistan with historical ones, like Mesopotamia and Khurasan, that fall between rather than within political boundaries. And even when countries are mentioned or depicted by militants, it is often in an explicitly global context where the US is viewed as part of a planetary crusader axis, and Iraq a portion of the global Muslim community under attack. Thus images of maps on jihad websites tend to locate particular countries in a planetary context, represent them floating in space like moons with the earth as a background, or portray them bleeding from wounds like parts of a global body.8 For alongside the environmentalists or pacifists who I will argue are their intellectual peers, the men and women inspired by Al-Qaeda’s militancy consider Muslim suffering to be a “humanitarian” cause that, like climate change or nuclear proliferation, must be addressed globally or not at all. So these militants take the whole planet as their arena of operations, shifting their attention from one site of Muslim suffering to another as if in a parody of humanitarian action, which indeed provides the paradoxical model for their violence.9

But the globalization of militancy has resulted in its fragmentation, this loss of institutional politics being compensated for by the invocation of humanity as both the agent and object of a planetary politics yet to come. Indeed we shall see that Osama bin Laden,

Ayman al-Zawahiri and the scattered flock they inspire refer almost obsessively to humanity in its modern incarnation as the sum total of the world’s inhabitants, whose well-being is measured by the twin practices of humanitarianism and human rights. In the eyes of these men, Muslims are not members of a religious group so much as the contemporary representatives of human suffering. And so those who go under the name Al-Qaeda do not for the most part target their enemies for holding mistaken religious beliefs or godless secular principles, but instead for betraying their own vision of a world subject to human rights. Whatever bad faith is involved in such an accusation, the crucial role it plays in the rhetoric of terrorism needs to be accounted for, given that arguments about humanity take precedence in this rhetoric over the scriptural citations whose medieval exoticism has seduced so many of those studying AlQaeda.

Anchored though they may legally be in the nation-state, human rights and humanitarianism in general provide militants with the terms by which to imagine a global politics of the future. In this way our terrorists have done nothing more than take up humanity’s historical role, which in earlier times was linked to the civilizing mission of European imperialism. In fact the promotion of human rights as a global project emerged within such empires while at the same time providing their justification. One has only to think of the abolition of slavery and Britain’s attempt to enforce its proscription outside her jurisdiction, along with the suppression of barbaric customs more generally, to realize that imperialism was in addition to everything else a humanitarian enterprise ostensibly dedicated to securing the lives and wellbeing of human beings in general.10 Indeed given that the language of citizenship was largely absent from colonial rule, it is perhaps no accident that its place there was taken by that of humanity instead. It is possible even in our own times to see imperialism at work as a global project in the steady replacement of the citizen by the human being, whose biological security now routinely trumps his rights of citizenship in anti-terror measures at home and humanitarian interventions abroad.

If imperialism broke the ground for a new kind of global politics based on humanitarianism, its foundations have been laid by the humanitarian interventions of post-colonial states, which include not only the great powers but even former colonies like India, whose intervention in the Pakistani civil war of 1971 represented one of the early forms that such a politics took. For its own part Pakistan was a pioneer in the invocation of humanitarian language to describe both militant “self-defence” in the valley of Kashmir and the “violations” to which India subjected its people.11 Since neither colonial nor postcolonial states have been able to instantiate a global humanitarian order, not least because they have been unwilling to sacrifice the politics of national and other interests for its sake, I will make the case that militants today aim at their unfulfilled goal. And in this way they are no different than the plethora of non-governmental agencies dedicated to humanitarian work. Indeed the accusation common among militants and NGOs, of the West being hypocritical in its promotion of human rights, is meant not to discredit but rather complete the latter’s globalization. These examples illustrate how intimately terrorist practices are linked with those of their enemies, whose humanitarian interventions also invariably kill some civilians in the name of protecting others.

My object in this book is to argue that a global society has come into being, but possesses as yet no political institutions proper to its name, and that new forms of militancy, like that of Al-Qaeda, achieve meaning in this institutional vacuum, while representing in their own way the search for a global politics. But from environmentalism to pacifism and beyond, such a politics can only be one that takes humanity itself as its object, not least because the threat of nuclear weapons or global warming can only be conceived of in human rather than national or even international terms. And so militant practices are informed by the same search that animates humanitarianism, which from human rights to humanitarian intervention has become the rhetorical aim and global signature of all politics today.12 This is the search for humanity as an agent and not simply the victim of history. While they possess different meanings

and genealogies deriving from eighteenth-century revolutions on the one hand to nineteenth-century colonialism on the other, we shall see that words like human rights and humanitarianism have since the Cold War been predicated of humanity as a new global reality, one whose collective life we can for the first time contemplate altering by our deeds either of omission or of commission. So for the militants among us, victimized Muslims represent not their religion so much as humanity itself, and terrorism the effort to turn mankind into an historical actor—since it is after all the globe’s only possible actor. For environmentalists and pacifists as much as for our holy warriors, a global humanity has in this way replaced an international proletariat as the Sleeping Beauty of history.

A global history of militant ideals

Al-Qaeda’s Spanish truce allows us to see how it is that globalization might provide the very substance of militant practices while still lacking an institutional politics. Yet globalization is the most ambiguous of processes, which, despite its current celebrity, remains curiously undefined as an analytical or historical category. On the one hand it seems to evoke the primacy of movement, whether of people, goods, ideas or money, that has supposedly increased to an unprecedented level both in rapidity and in extent. On the other hand globalization evokes a theory of capitalism that would enclose all the social possibilities and experiential implications of such movement within a singular history of economic reach. In either case this movement is supposed to be made possible in large part by new technologies, which thus mediate it as a kind of ever-renewed present, globalization as the newest of the new.

The problem with conceiving of globalization as a movement mediated by technology into some ever-renewed present is that it ceases to have a past, properly speaking. And this is because the difference between its form of movement and any other is one of degree rather than of kind. For instance how is the Internet more illustrative of globalization than the telegraph, or today’s virtual

economy more global than yesterday’s finance capitalism? No matter how radical their repercussions, do the new technologies mark new beginnings, or do they simply exist in the wake of older ones? This problem of historical and analytical regress exists only because accounts of globalization tend to be seduced both by the narcissism of the present, and by the glamorous novelty of its objects or experiences, in the process quite dispensing with the term’s intellectual genealogy But it is precisely this genealogy that may allow us to lend the globe some historical as well as conceptual substance.

When was it that the globe, and therefore the possibility of globalization, ceased to be a classroom model or a geographical abstraction and became real? At what point did the globe part company with the notion of world, itself connected to a particular religious history in terms like worldliness, to mark a new beginning? Languages like French, of course, continue to derive globalization (mondialisation) from the older notion of world (monde), thus linking it back to another kind of history. The earth, too, continues to be used as a synonym for the globe, though its frame of reference is the solar system rather than humanity’s political or ecological existence.13 Nevertheless there is a point when we can say that the globe subordinates all these competitors and becomes, as it were, global, a point we can for our purposes locate during the Cold War. The latter made today’s militancy possible by lending political reality to previously abstract categories like the global Muslim community, which is why Al-Qaeda’s acolytes very self-consciously derive their jihad from its last great battle in Afghanistan. For it was during the Cold War that two great ideals shaping the practices of both militants and their enemies, the globe as well as the humanity that inhabits it, achieved an ambiguous political reality.

The Cold War had for the first time put the globe itself at stake in the practice of politics, by dividing it into two rival hemispheres.14 Moreover two of its greatest technological events, the atom bomb and the moon landing, permitted us not only to grasp and see the globe as such, but also and in the same moment to conceive of its

destruction and abandonment. In this way Cold War technology simultaneously consolidated and transformed the earlier but more abstract experience afforded us by the globe’s circumnavigation. The earth, then, like some gigantic commodity, is known only in the moment of its consumption as something capable of being destroyed or abandoned. This apocalyptic manner of knowing the planet allows thought in general, and religious thought in particular, to contemplate as real something that had been denied legitimacy for two centuries —the end of the world. It is in the rapture of apocalypse that the world is destroyed and the globe born, even if only as the ghost of this world.

The birth of the globe during the Cold War did not go unnoticed, its implications being noted by the philosopher Hannah Arendt among others. In an essay on her colleague and friend Karl Jaspers, who had himself expounded the phenomenology of a nuclear apocalypse, Arendt wrote about the ironic global unity that the atom bomb had made possible:

It is true, for the first time in history all peoples on earth have a common present: no event of any importance in the history of one country can remain a marginal accident in the history of any other. Every country has become the almost immediate neighbor of every other country, and every man feels the shock of events which take place at the other side of the globe. But this common factual present is not based on a common past and does not in the least guarantee a common future Technology, having provided the unity of the world, can just as easily destroy it and the means of global communication were designed side by side with means of possible global destruction.15

The question Hannah Arendt tackles in her essay is not the practical one of how to prevent an apocalypse, but rather one that interrogates the new experience that its destructive possibilities brings into being. Apocalypse, in other words, refers in her essay not to the brute fact of nuclear destruction, nor to the ecological holocaust that is its heir. It names rather the new experience of the globe and thus of humanity also that the very possibility of this destruction brings to light. So according to Arendt the unity of the globe that technology produces is purely negative because it is

based neither on a common past nor on a common future, relying instead on the experience of an evacuated present in which disparate histories mingle promiscuously. The reality of globalization, in other words, is premised upon an apocalypse that has not occurred, something that lends its experience an anticipatory though not necessarily a millenarian character, as its cause is human and not divine.

Yet the experience of a possible apocalypse is a manifestly inhuman one, since the globe’s desolation can only be conceived from a point of view set outside it, and therefore outside human reality as well. In theory modern science had accepted the inhumanity of such an experience well before the Cold War, by repudiating both geocentric and anthropocentric points of view, so that nuclear physicists had no hesitation in splitting the atom the moment it became possible to do so.16 But it took the atom bomb and the moon landing to make this experience part of everyday reality. To see the globe, and the humanity that inhabits it, as if from outer space, is to abandon a humanistic point of view by abandoning the scale at which human beings live, defined as this is by the horizon of their senses.17 From such a distance the globe and its inhabitants can only be approached in a technical way, by interventions of constructive as much as destructive import, whose agents end up losing their own humanity in the process. To be capable of approaching the globe and its inhabitants technically is to be almost divine. The globe is therefore strictly speaking an inhuman reality, or rather one that renders humanism and its point of view redundant.

The globe becomes real at the same time as humanity, which serves both as the agent and the victim of its possible demise. For mankind is now no longer an ideal or an abstraction, but a reality too insofar as it is capable of being destroyed.18 Indeed in this sense humanity achieves reality in the same way as the human being, by recognizing its own mortality, though humanity’s gigantic reality is of course as inhuman as that of the globe. It is the technology of destruction and abandonment that permits humanity to emerge as

an historical actor for the first time by undoing the particularity of its own origins. Thus it is mankind, rather than the United States of America, which became the true agent of global events like the atom bomb or moon landing.

The Cold War provided the origins of globalization as this term is used today, and in particular as it lends substance to new forms of militancy by making the Muslim community into a global reality for the first time along with the humanity it represents. It did so by replacing the world with the globe and man by mankind, all within the horizon demarcated by an apocalyptic technology, whose power subordinated all links with the past to the false unity of a global present in which distinct historical traditions come to be juxtaposed with one another. In the process globalization came to replace internationalism, which had been the ideology both of the European empires and of the Communist bloc. These orders were international because they were based on the expansion of a substance (civilization, justice, freedom and the like) in territories that were connected either by geographical or by historical contiguities. Globalization, on the other hand, depends neither on the diffusion of a substance, nor upon historical and political links, but precisely on the unintended effects and consequences that constitute its universal present.

The apocalyptic tone of Cold War thinking might have dissipated today, but its spirit continues to haunt globalization. So the atom bomb has been replaced by ecological and other threats that all take on the characteristics of an explosion, insofar as they are capable of wreaking havoc upon a humanity made interdependent by technology. Such bombs need not even destroy human lives to mimic and indeed foreshadow the global effect of their nuclear cousins. Media, for example, continually ape the apocalyptic effect of an empty present, because they bring together widely scattered constituencies in the contemplation of an event deemed newsworthy even if it occurs in some remote corner of the world with which these audiences have no real connection, and which does not even represent a substance spread by connections of geography or history. The rupture with internationalism here is absolute because

the global effect of the media’s information bomb is not due to consequences that go beyond particular intentions, but rather to the false unity of a present made possible by ideas, events and fashions that can only function randomly once separated from local histories. It is the apocalyptic nature of globalization that might explain why Al-Qaeda’s mobile and dispersed militants are not linked vertically, by a common origin, organization or purpose, but horizontally by sartorial, linguistic and terrorist practices made available through the media much like fashions in dress, music or behavior are. However local their aims and origins, therefore, such men are connected by global practices that lend them an existential rather than historical or political unity. In the spring of 2008, for instance, revelations that an American soldier in Iraq had used a copy of the Quran for target practice led to demonstrations in Afghanistan at which three protesters were killed. While it is clear that these demonstrations had little connection with anything going on in Iraq, it is also evident that the protests could not be confined to their locality. Such practices are global not merely because they happen to be dispersed across the planet, but also because they are meant to appropriate and even colonize it as a site of militant activity by the creation of violent spectacles.19 Rather than existing for these terrorists as some imaginary and in any case predefined arena of operations, the globe is both produced and inhabited by them in the form of televised events.

The shape of things to come

How is it possible to be a political actor in the false unity of a globalization with no common past or future—one in which mankind has replaced man as the agent and victim of history? This precisely is the problem of militancy, whose votaries know that while everyone today speaks of a single world and a single humanity, neither one nor the other has a political life of its own. At most there exists the partial humanity of aid and relief work, defined in numerical terms as a mass of victims who cannot all be ministered to. Humanitarianism

thus operates by a calculus in which the lesser number of victims must be sacrificed for the greater. Like terrorism, in other words, it depends upon sacrificing the few for the many—which also means sacrificing those suffering smaller afflictions in order to attend to bigger ones. And just like Al-Qaeda’s militants, humanitarian agencies have abandoned previously exempt subjects like women and children to this calculus of sacrifice, thus bringing humanity into being in the same way as an atomic holocaust, by number alone. Here, then, is a fine example of the inhuman nature of gigantic realities like humanity, which can only be approached by technical means.

The experience of globalization made possible by the atom bomb defines the humanity that both militants and humanitarians are concerned with in quite specific ways. Writing after the First World War, for example, the jurist Carl Schmitt had argued that the emergence of humanity as a political category entailed the appearance of its opposite as well. The very idea of fighting a war for humanity, after all, makes the enemy into someone not quite human who might be sacrificed without scruple.20 For Schmitt, then, humanity becomes real only by practising the most inhuman cruelty. Putting this argument in another way, the philosopher Etienne Balibar has noted that attempts to instantiate humanity tend to be racist in character because they result in a hierarchy of those who are more and those who are less human, this process of exclusion providing the only way by which humanity might become manifest.21 The atom bomb, however, produces a truly inclusive form of humanity, whose suicidal potential no longer allows its inhuman or subhuman opposite to remain external to itself, instead absorbing them into its own gigantic reality. The idea of a suicidal humanity became a political truism in the atomic age, and now defines the victims of other potential holocausts, whether environmental or even terrorist. For is not the suicide bomber only the miniaturized version of a suicidal humanity?

My comparison of today’s suicide bomber with yesterday’s suicidal humanity is not a casual one, for we shall see that neither is