1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Yandell, Kay, 1968–author.

Title: Telegraphies : indigeneity, identity, and nation in America’s nineteenth-century virtual realm / Kay Yandell.

Other titles: Indigeneity, identity, and nation in America’s nineteenth-century virtual realm

Description: New York : Oxford University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018013259 | ISBN 9780190901042 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780190901066 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190901059 (updf)

Subjects: LCSH: American literature—19th century—History and criticism. | Telecommunication in literature. | Telegraph in literature. | National characteristics, American, in literature.

Classification: LCC PS217.T53 Y36 2018 | DDC 810.9/003—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018013259

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

For Auster-Aurelio Unole Yandell-Teuton, born 20 August 2009

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments ix

Introduction: A Virtual Realm in Morse’s Dot and Dash 1

1. Moccasin Telegraph: Telecommunication across Native America 24

2. Crossing Border Wires: Telegraphers’ Literatures and the State of American Union 56

3. Corsets with Copper Wire: Victorian America’s Cyborg Feminists 81

4. Emily Dickinson’s Telegrams from God 105

5. Engineering Eden in Walt Whitman’s “Passage to India” 129

Conclusion: Hawthorne’s Celestial Telegraph and the Cycle of History 158

Notes 177

Index 201

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I’ve enjoyed the good fortune to have many colleagues, friends, and family members who have shared their time and thoughts with me as I’ve written this book. Roger Gilbert, Laura Donaldson, and especially Laura Brown read first drafts of chapters and gave detailed responses, and I thank them very much for their guidance.

David Zimmerman, Roberta Hill, Jeffrey Steele, and especially Russ Castronovo read various drafts and offered meticulous reports that improved the book before I sent it for press review. Russ Castronovo also helped me understand the market demands of book publishing in ways that undoubtedly caused publishers to receive my manuscript more warmly.

My tireless advocate, editor, and friend Craig Werner offered insight on the manuscript as a whole, coached me, as he has coached so many scholars, through the editorial process, and simply improved my life greatly by always being there when I needed him.

I must especially thank Priscilla Wald for accepting a version of chapter 1 for publication in American Literature; the prize committees who awarded that essay the Don D. Walker Prize for Best Essay Published in Western American Literary Studies, and honorable mention for the Norman Foerster Prize for Best Article Published in American Literature of course made me feel just wonderful, and also helped to garner interest for the larger work.

I thank my wonderful English Department colleagues at the University of Arkansas. Conversations with fellow Americanists Lisa Hinrichsen and Susan Marren never fail to sharpen my thinking. The prize committee who awarded me the Ray Lewis White Publications Award contributed research funds that I used toward this and subsequent books. Dorothy Stephens I must thank for more help than I can name here, probably more than I can remember that I owe her.

The readers for Oxford University Press offered suggestions for changes to the manuscript which, though they differed greatly from each other, helped me take

the book in new directions that surprised even me. Sarah Pirovitz and Abigail Johnson have been absolute godsends, and their work to convey information with and from my anonymous press readers, and to organize book production, assured that the book reached publication.

My final thanks go, as always, to my beloved late parents, Bobby and Brian Yandell, and to my husband Sean Teuton, for their love and support. Sean, together you and I have done what at times seemed impossible: built two academic careers while raising four glorious children. Together, there is apparently little we cannot accomplish.

Introduction

A Virtual Realm in Morse’s Dot and Dash

In 1844, Samuel Morse (1791–1872) strung a wire between Washington, DC, and Baltimore, Maryland, and sent America’s first official telegram. From that day in Baltimore, Americans conceived in the electromagnetic telegraph a social revolution as sweeping as those produced by the printing press in the fifteenth century or by the internet in the twentieth century.1 As human speech went electric, nineteenth-century Americans perceived it to enter another disembodied electric realm, a realm held aloft either metaphorically or physically by the new telegraph wires. This realm of perceived instantaneous, disembodied electric talk, for which nineteenth-century writers used an array of terms, we might today productively invoke as nineteenth-century America’s own progenitor virtual realm. 2 The body of literature inspired by and imagining this earlier manifestation of the virtual realm constitutes one subject of this book.

Though many of the era’s authors represent his work as revolutionary, in technical terms Morse invented neither the telegraph nor the electric telegraph. With the help of scientists who knew better than he how to construct the device, he did, however, adapt existing technology to create a machine that set new telecommunication standards, first for the Americas and then for the world. Morse’s machine eventually predominated because of its simplicity. Its basic form consists of a single wire with metal contacts at each end. These contacts separate or touch to open or close the electrical circuit, producing either silence when the circuit opens, or a buzzing sound when it closes. Using Morse Code, an operator turns this buzzing sound on and off to produce a series of long and short buzzes, called dashes and dots respectively. A few dots or dashes combine to form the code for each letter of the alphabet, number, or punctuation mark. An operator next assembles the symbols into words and sentences. By modern standards, of course, Morse composition entails an agonizingly slow process, but by the standards of the 1850s, Americans of all ranks stood in wonder at this

miracle machine, ubiquitously touted to speak so rapidly across such inconceivable distances as to have “eliminated the boundaries of time and space.”

In social terms, it was the electromagnetic telegraph’s relative speed of communication that incited what we now call a telecommunications revolution. In 1841, for example, public information took an average of eight days to travel from New York to Detroit, ten days to move from New York to Chicago, and it typically moved out to smaller towns only after arriving at metropolitan hubs.3 As the wires spread worldwide, however, communications between New York and London, which had previously taken ten days as letters arrived by ship, by 1858 might take only a few minutes. As the transcontinental telegraph replaced the Pony Express beginning in 1861, U.S. citizens gained a new, if short-lived, sense of national identity: telegraph pioneer James D. Reid, for instance, celebrates a new conception of national union girded by Morse’s “magic belt of fire” that united the Atlantic and Pacific coasts.4 Telegraphy radically changed not only the practices of whole societies on a mass scale, but also the awareness of individuals from all social locations. As chapter 3 of this study will treat in detail, because they desperately needed the skilled labor, telegraph companies opened the position of telegrapher to women, allowing many women previously unimagined opportunities for financial support, travel, and access to government, business, and personal news that many men of the era did not possess. Businessmen had immediately to change their financial theories to accommodate stock-exchange information and orders arriving “instantaneously” from afar. As the wires transmitted each newspaper story entering citizens’ homes more directly from a reporter on the scene, national news began to take precedence over local news, the political opinions accompanying news became more homogenous nationwide, and newspaper prose itself became more declarative and truncated to avoid the modification errors that more periodic sentences could cause telegraphers. Telegraph instruments filled city office buildings as the wires initiated new standards for business and government communications, and though personal telegrams remained expensive, they decreased in relative cost as the century progressed. By the 1880s, middle-class Americans commonly telegraphed personal news requiring a quick response, and as the telegraphers’ writings investigated in chapter 2 show, office workers’ use of company machines for personal communication insured that electric speech became accessible to telegraphically skilled members of the working class as well. One telegrapher explains his personal use of company lines to speak with his faraway sweetheart after hours: she “bribed the burly porter . . . to lend [her]. . . a key” to the building, and then the lovers communicate by listening to the beeping sounder but without using the ticker tape that records messages in written Morse: “[I listened] off the Morse instrument without letting the paper run.”5 As chapter 2 will detail, however, the physical working conditions of telegraphers

remained harsh: operators worked ten- and twelve-hour days. Companies held railroad telegraphers responsible for large amounts of cash arriving by train, and fined or fired them if they were robbed. These and other abuses cause us better to understand the second half of the nineteenth century—the age of telegraph expansion—as the great age of worker organization and violent corporate suppression, a fact voluminously treated in what, for the purposes of this study, I refer to as telegraph literature.

This book analyzes telegraph literature—the fiction, poetry, social critique, and autobiography that experiences of telegraphy inspired authors from vastly different social locations to create throughout mid- and late nineteenth-century America. The possibilities afforded by the telegraphic virtual realm inspired numerous authors to explore how this seemingly instantaneous, disembodied, nationwide speech, its accompanying truncated and coded telegram form, and the physical web of copper wires it spread over the American continent challenged American conceptions of self, text, place, nation, and God. Canonical American authors, including Horatio Alger, Emily Dickinson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry David Thoreau, and Walt Whitman, joined such lesser known authors as Ella Thayer, Lida Churchill, and Sarah Winnemucca to imagine in their writings the import of telegraphic speech. The chapters that follow investigate a substantial and diverse but underexamined body of nineteenth-century American literature about different types of telegraphs; these literatures nonetheless have enough in common that I find it productive to group them as their own telegraph literature subgenre. Authors of telegraph literature craft what I have called their “progenitor virtual realm,” a proliferation of alternative disembodied worlds, frequently imagined as especially utopic or dystopic. Such alternative worlds I term disembodied technotopias. Telegraph literature often envisions its virtual realm as a sort of laboratory in which to test new hypotheses of place making, personal identity, and political transformation. Authors and readers of telegraph literature often seek to enact their virtual-realm technotopias in the physical world, in ways that stretch many current critical definitions of nineteenth-century identity performance and political imagination. Nineteenth-century authors writing about Morse’s machine celebrate the telegraph’s ability to unite speakers “instantaneously” across vast distances, in new and specifically user-created virtual worlds. By analyzing the discourse created within these virtual worlds, I hope to add new dimensions to Elaine Scarry’s definitions of the verbal arts: though they “are almost wholly devoid of actual sensory content,” the verbal arts “somehow do acquire the vivacity of actual perceptual objects,” or, if we admit telegraphic virtual speech as an art, even of extraperceptual objects in a world where objects and characters potentially escape the laws of the physically possible.6 Telegraphic interlocutors often perceived their virtual speech acts to occur for the first time in ways unlocatable within such traditional communication modes as embodied

face, age, ethnicity, gender, class, voice, accent, location, or even disembodied signature or handwriting. Many authors of telegraph literature, this book argues, thus actively appropriated the nineteenth-century virtual realm as its own sort of disembodied second life, as a sort of impromptu theatrical stage whose virtual sets and dramatis personae—prototypes perhaps of a later era’s online avatars— could not only be manipulated by their users, but could also perform as experimental selves that actors could pull down from their virtual worlds to model new forms of subjectivity in an embodied and geographically bound, but often equally idealized, young nation.

The following chapters’ individual arguments interlock to access from different angles the high political stakes that repeatedly arise throughout telegraph literature. For example, nineteenth-century American authors imagined the virtual realm in many ways, but recurringly as a site of competition for control over social constructions of indigeneity, identity, and community in a young nation. Some telegraph authors, for example, imagined the virtual realm specifically through analogies of place, as a sort of nation. They often imagine this virtual literary nation as analogous to the U.S. nation, complete with nineteenth-century desires for western lands and the attendant justifications of U.S. imperialism. Indeed, the telegraph literature this book studies emerged from a historical moment that made a primary project of wresting American land from Native Americans.7 This book argues that, perhaps as a result of the era’s settlementbuilding projects, some authors of telegraph literature tended to test in their virtual nations what they conceived as a new sense of place through which better to connect with recently acquired and inhabited, and therefore potentially alien, embodied American lands. To do so, this book argues, some telegraph literatures sought to spread distinctly mythicized European American stories, alongside U.S. histories, through the wires being strung across otherwise unknown American geographies. Perhaps because telegraph literature so often specifically treats relationships to land, however, the new myths spread via telegraph, and became monumentalized in telegraph literature, in ways surprisingly often designed to emulate, and simultaneously to overwrite, the similarly orally disseminated literatures informing the sense of place of the land’s previous Native American inhabitants.

This book seeks to balance attention to such imperialistic, racialized, or gendered impulses in telegraph literature by emphasizing other writers who use long-distance communication modes in the service of colonial resistance, who infiltrate Morse’s own discourse networks to empower minority communities, or who literarily reclaim telegraphic operation to redress past wrongs. While Walt Whitman, for example, might celebrate telegraphic organization of colonial settlement (see chapter 5), Nathaniel Hawthorne imagines telegraphic networks that force Americans to admit and redress their ancestors’ past land thefts (see

the conclusion). To imperialist technotopias imagining that telegraphy can disseminate their nation’s origin myths and thus sacralize settlers’ connections to American lands, this study contrasts literatures presenting Native Americans’ own visions of telegraphy. As chapter 1 will treat in more detail, long before nonNative settlers arrived, American Native peoples used extensive and powerful telecommunication systems to enact their own political goals, and to carry the mythic stories that attach their own histories to American lands. These previously existing telecommunication systems, which telegraph literature sometimes refer to as the moccasin telegraph, vied with and sometimes bested Morse telegraphy along the frontier, even as Native peoples simultaneously appropriated Morse telegraphy toward their own political ends.

Telegraph literature also implicitly debates the ways that users might stabilize or challenge identity—with its attendant hierarchies of region, class, ethnicity, or gender—through their use of the virtual realm. Some authors theorize the social purpose of electric speech by imagining that traditional definitions of community and personal identity inhere within the new virtual realm. Such insistence on stable identity hierarchies within intertwined virtual and physical new worlds might arise as a response to the panic of anxiety and hope that emerged in consideration of the virtual realm’s power fundamentally to alter all formulations of American identity. Within telegraph literature’s self-conscious remaking of place in a new America, therefore, this book investigates an alternative problematic within technotopias that hypothesize radically new formations of subjectivity and community to argue, not only that speakers theorize and practice new identities in the virtual realm, but also that the perceived disembodied nature of the virtual enables new conceptions of what can count as an identity, potentially in ways that transcend the bounds of the previously imagined possible. Once technotopically conceived, such new subjectivities could nonetheless be enacted to varying degrees in the physical world of a burgeoning nation.

Concerns surrounding virtual identity seem to pervade telegraph literature in response to authors’ awareness that one’s choice of online persona and community directly affects real-world power relations. While stressing the ephemeral, unlocatable nature of this virtual realm, then, authors of the technotopic virtual nonetheless recognized the earth-shaking power that decisions made there had on lives socially located in the physical world. We see this influence in such examples as the following, in which by dominating the virtual realm, social elites can determine what even nonusers of the telegraph learn about their world through the newspapers.

Beginning in 1846, only two years after Morse’s first public telegraph demonstration, the heads of the major New York newspapers held a series of meetings to secure their respective market shares against several newer, cheaper, more salacious newspapers that threatened to overtake the city’s news markets. “Where

were these meetings held?” historians of the events later asked. “Nowhere,” they were told. “Was it difficult to convene meetings between newspaper moguls of celebrity status?” “No,” answered the founders, because they rarely physically convened. Rather, the newspaper leaders met in the progenitor virtual realm, via the very telegraph network—thereafter called the Associated Press (AP) Wire Network—that soon assured their market dominance by allowing their collective to release news earlier than the smaller papers. More importantly, the AP wire network allowed these editors to guide interpretations of news—what we today commonly call “spin”—to homogenize public opinion of events, creating what Menahem Blondheim identifies as a “monopoly of knowledge.”8 Only two years after Morse’s first demonstrational line, then, the powerful had largely appropriated the telegraphic virtual for their own political motives, attempting, as James Carey and Harold Innis observe, to “determine the entire world view of a people,” to create “an official view of reality which can constrain and control human action.”9 But even as America’s predominant telegraph network increasingly enmeshed the continent, telegraph systems outgrew their builders’ desires for complete corporate or governmental control. Resistant American identities of all sorts infiltrated telegraphic discourse with vigor and imagination and, often, with surprising success.

Having addressed some of the main political stakes that recur throughout telegraph literature, I now address the historicity of the modern internet terms that I invoke as lenses through which to view the telegraphic literary and social revolution. Some recent critics have viewed telegraphic speech modes through descriptions we more typically reserve for its great-grandchild, the internet. In his history of British and other historical telegraphs, journalist Tom Standage, in fact, dubs nineteenth-century telegraphy the “Victorian Internet.” Readers will have noticed that this book, too, sometimes retroactively applies internet terms—virtual realm, the Web, online identity, avatars, chat rooms metaphorically to nineteenth-century telegraphic speech forums, in instances that are in some aspects necessarily anachronistic. I do not seek within the bounds of this study precisely to delineate how appropriately or inappropriately such terms parallel telegraphic speech practices or perceptions in any given literary work or historical example. Rather, while I fully invite readers to gauge the extent to which specific telegraphic interactions converge with or diverge from internet discourse, I invoke such terms more because they do in so many instances seem to align with nineteenth-century perceptions of telegraphic speech, and because they allow first-generation internet readers, fully aware that the Web has performed a paradigm shift in our own worldviews, better to envision the shock, wonder, and excitement similarly experienced by the first generations of telegraphic speakers. Other recent critics more frequently apply virtual-age terminology to nineteenth-century literature to refer to characters’

interior worlds as virtual realities or to fictions written about a physical landmark as that site’s virtual existence.10 My study differs from such considerations of the virtual in nineteenth-century literature in that I am investigating a phenomenon much closer to our own era’s daily encounter with the virtual—a specifically technologically accessed and user-created fantasy world in which one nominally speaks in real time and in which one’s virtual identity potentially exceeds the physical boundaries of the otherwise experientially possible. In so doing, I engage the ways that use of the telegraphic virtual drastically alters both everyday behavior and human consciousness in the literature of mid- and late nineteenthcentury America.

My arguments for how the nineteenth-century virtual changed American literature also provide an exception to the predominant—and I think equally valid—readings that locate in telegraphy the birth of a fractured modern consciousness and of modernist aesthetic movements. Many current critiques emphasize telegraphic speech as the instigator of such modern social problems as performance decline while multitasking, attention deficit disorder, increased physical disability, and a preference for mediated over personal intimacy. Friedrich Kittler reads alienation in nineteenth-century mass media that introduce “the irruption of the mechanism in the realm of the word.” For Maggie Jackson, telegraphic “experimentation with mediated experience and the control of perception has helped inure us to a world of fragmented, diffused, and manipulated attention.”11 Sherry Turkle demonstrates that we choose mediated communications over personal interactions to create the illusion of companionship without the emotional demands of friendship.12

Kittler’s association of mechanized speech forms with modernist aesthetics redounds throughout current criticism of the telegraph. Theorists of telegraphy’s effect on literature often underscore the role of mechanized transmissions on formations of more intensely realist forms and perceptions, and of fractured modernist ontologies and aesthetics. For Richard Menke, one “powerful expression of . . . media shifts . . . is . . . fictional realism.” Mark Goble investigates “the way that modernist expression wants to wire bodies into circuits.” Jennifer Raab names as “telegraphic” the “fragmented transmission” and “particularly modern character” of some nineteenth-century American travel writing.13 Although these equally valid studies form helpful delineating contexts for my own, my study traces a different impulse within telegraph literature, one in which writers romanticize telegraphic form and imagine for telegraphy the power to create idealized new worlds. My emphasis on such distinctly romantic aesthetics of much American telegraph literature to build utopias for subsequent enactment in the physical world sets Telegraphies apart from many recent understandings of the effect of telegraphy and related technologies on literature.

Having delineated some of this study’s major approaches and structuring concerns, I’d now like to give an instance of the sort of highly romanticized and politicized technotopia we frequently find in nineteenth-century American telegraph literature. This fantasy of telegraphically enabled control over American land, resistant ethnic groups, and women’s social roles serves as a model of the imperialist technotopias that I will reference throughout this study, but it also stands as precisely the sort of fantasy that the more liberatory literatures treated later in the book will seek directly to resist.

Imperialist Technotopias on the American Frontier

As John Crawford (1847–1917) recovered at an army hospital from his Civil War battle wounds, his nurses taught him to read and write. After the war, Crawford published poems and stories while working as a soldier in the Indian Wars and a performer in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, and he developed a literary career as a self-described “U.S. Cavalry Scout Poet.” “Captain Jack” Crawford’s 1894 serialized fiction “Carrie” opens with what its first-person narrator, Fred Saunders, describes as an “enigmatical” relationship between himself and the eponymous object of his affection. “I found myself falling in love with her,” he says, “yet I had not the least tangible idea of her personal appearance, and knew not whether her voice was soft and musical or . . . harsh and disagreeable . . . . This may all seem enigmatical to the reader, but will assume an aspect of entire plausibility in the light of the fact that she and I were telegraph operators at widely separated stations on a western railway.”14

The story’s first paragraph introduces to nineteenth-century readers the mystery of how Fred can fall in love with a woman he “had not met”; the second paragraph, quoted here, solves the mystery as readers realize with pleasure that the pair consort in a way they could not have guessed—by telegraph. This mystery can exist at all, and can inspire what the story presents as a novel plotline, because telegraphers Carrie and Fred find their disembodied love in a moment when, in the minds of most Americans, talk itself has transformed forever. As the story enacts Crawford’s fantasies for telegraphic control—of gender, indigeneity, class, and imperialism—it neatly registers many major nexuses of contention in telegraph literature. Crawford stages “Carrie” in its own virtual Wild West show, a literary technotopia heavily informed by and informing Crawford’s literary persona and national reputation as a U.S. Frontier Cavalry Scout and Poet. Crawford’s title names “Carrie, the Telegraph Girl” as “A Romance of the Cherokee Strip.”15 The reference to the Cherokee Strip links Crawford’s virtualrealm fiction to the geographical location of the 1893 Cherokee Outlet land run.

Congress had promised to the Cherokee Nation in perpetuity the area of Indian Territory known as the Cherokee Outlet, but it then pressured the tribe to sell the land and opened the Outlet to the largest settler land run in world history. Crawford’s story is set just before the land run, however, in the transfrontier “wilderness”16 of 1892 Indian Territory “inhabited only by Indians . . . and roving bands of desperadoes under the leadership of the Dalton brothers.”17 At the point in the story when Fred and Carrie finally meet in person at Fred’s railroad telegraph station, the seeming spirit of this untamed American wilderness itself, here instanced through twinned threats from wild Indians and the Dalton Gang desperados, interrupts the lovers’ plans for a physical domestication of their heretofore disembodied attraction. As Carrie visits the station’s freight room for a drink, and Fred decides “that a lifetime spent in her society would not weary me,” the Dalton Gang bursts through the door, threatening Fred’s fantasies of civilizing the wilderness with a homestead and family, Carrie’s maiden virtue, and the railroad’s westward progress: the Daltons threaten to kill Fred, rape Carrie—“what indignities might not be offered her by these . . . cruel, reckless men who had less regard for women than for dumb brutes”—and rob the train that will arrive at the station shortly. Unnerved by “this harsh transformation from a blissful dream of love to the very precincts of death,” Fred dashes for the telegraph sounder to call the sheriff to restore order, but a Dalton bullet to his leg stops him short. While Fred lies bleeding, Carrie “the Telegraph Girl” appropriates the station’s outgoing telegraph wires to save Fred, but also to protect corporate profits and colonial control of newly won Native land as “duty demands”: Carrie climbs a ladder from the freight room to the attic, whence she taps the end of an outgoing wire with anything metal to telegraph “the keeneared night guardians of the company’s interests.” These fellow telegraphers at nearby stations send the “sheriff’s posse” on the next train crossing the frontier west into Indian Territory. The telegraph even allows Fred and Carrie to converse in Morse Code under the very noses of the Daltons. Over the beeping sounder, Fred hears Carrie telegraph her fear that he has been killed by the shot she heard; for her benefit, he loudly describes his wounds “to the Daltons,” and Carrie responds by wiring for a doctor and explaining the case that awaits his arrival, then speaks directly to Fred on the sounder: “I will be with you the minute the train gets here—Cr.”

Telegraph literature sometimes ends with the text of a telegram inserted directly into the narrative in a way that allows the story’s real hero—the telegraph itself—to speak the story’s denouement. In “Carrie,” this telegram arrives in the next scene, set at the telegraphers’ wedding. The telegram fictively arrives from the actual superintendent of Western Union, R. B. Gemmell, to assert that the telegraphy of “our little heroine” has indeed restored the conventional orderings of European American erotic process and familial structure, corporate

profitability, colonization of Indian Territory, and government control of its wild inhabitants. The telegram informs us that Carrie will quit her job to settle one more European American family in Indian Territory: “We regret the loss of the valued services of our little heroine.” The Dalton Gang’s train robberies will cease. In fact, Crawford wrote the story to commemorate the fact that “Bill Dalton was punctured by a well-directed bullet from the rifle of a deputy United States marshal but a few days ago.” The Oklahoma land run will take place on land cleared of resistant Native inhabitants, and Fred will escape the workingclass realities of a job as a telegrapher through the $2,000 reward that Gemmell has wired along with the story’s technotopic telegram.

This resolution also serves literarily to inscribe Captain Jack Crawford’s technotopia onto the physical world, as Fred announces this fiction as factual American history: “Were I dealing with fiction I would write a lurid description of a desperate conflict between the sheriff’s posse and the outlaws, but as I am dealing in actual experiences . . . I must adhere closely to the lines of truth.” Such insistent infusion of technotopic virtual-realm fantasy into American history in the making recalls the larger metaphysical power of Crawford’s storied telegraph in his technotopic world. Crawford’s 1894 story accords the telegraph the power to clear the transfrontier wilderness of “prowling Indian[s]” and “reckless men” so that the frontier may push inevitably westward; so doing, it invokes Frederick Jackson Turner’s famous pronouncement, published just the year before Crawford’s story, that the American frontier between Indian savagery and European American civilization had just closed. Perhaps most productively read considering Turner’s “Frontier Thesis,” Crawford’s story names the telegraph as the central tool of the racial and cultural evolution Turner perceived to occur on the American land along its ever-westering frontier line. Indeed, Turner’s essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” (1893) mentions Crawford’s specific local frontier, “the present eastern boundary of Indian Territory,” and naturalizes “communication with the East” as the network of “nerves” that close this frontier and replace the savages’ wilderness with an increasingly “civilized,” increasingly European American United States: “[T]he wilderness has been interpenetrated by lines of civilization growing ever more numerous. [Through] the steady growth of a complex nervous system for the originally simple, inert continent . . . we are to-day one nation, rather than a collection of isolated states . . . . In this progress from savage conditions lie topics for the evolutionist.”18 Crawford fictively answers Turner’s call to “evolutionists” (Turner means social evolutionists), to reveal the telegraph as the metaphysical key that accomplishes Turner’s equally metaphysical racial and cultural evolution along the American frontier.

Crawford endeavored to enact his telegraphically enabled Wild West technotopia in his own life as well. As chief scout with Buffalo Bill Cody of the

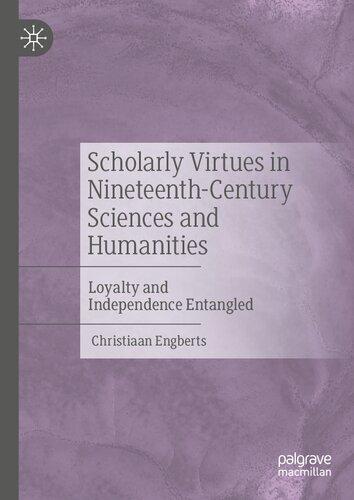

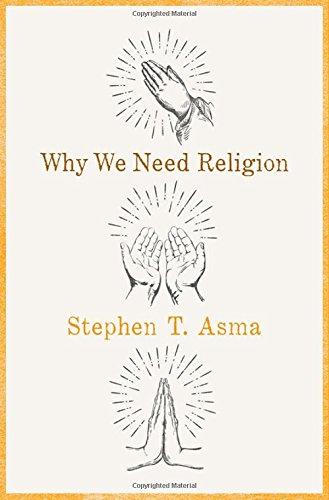

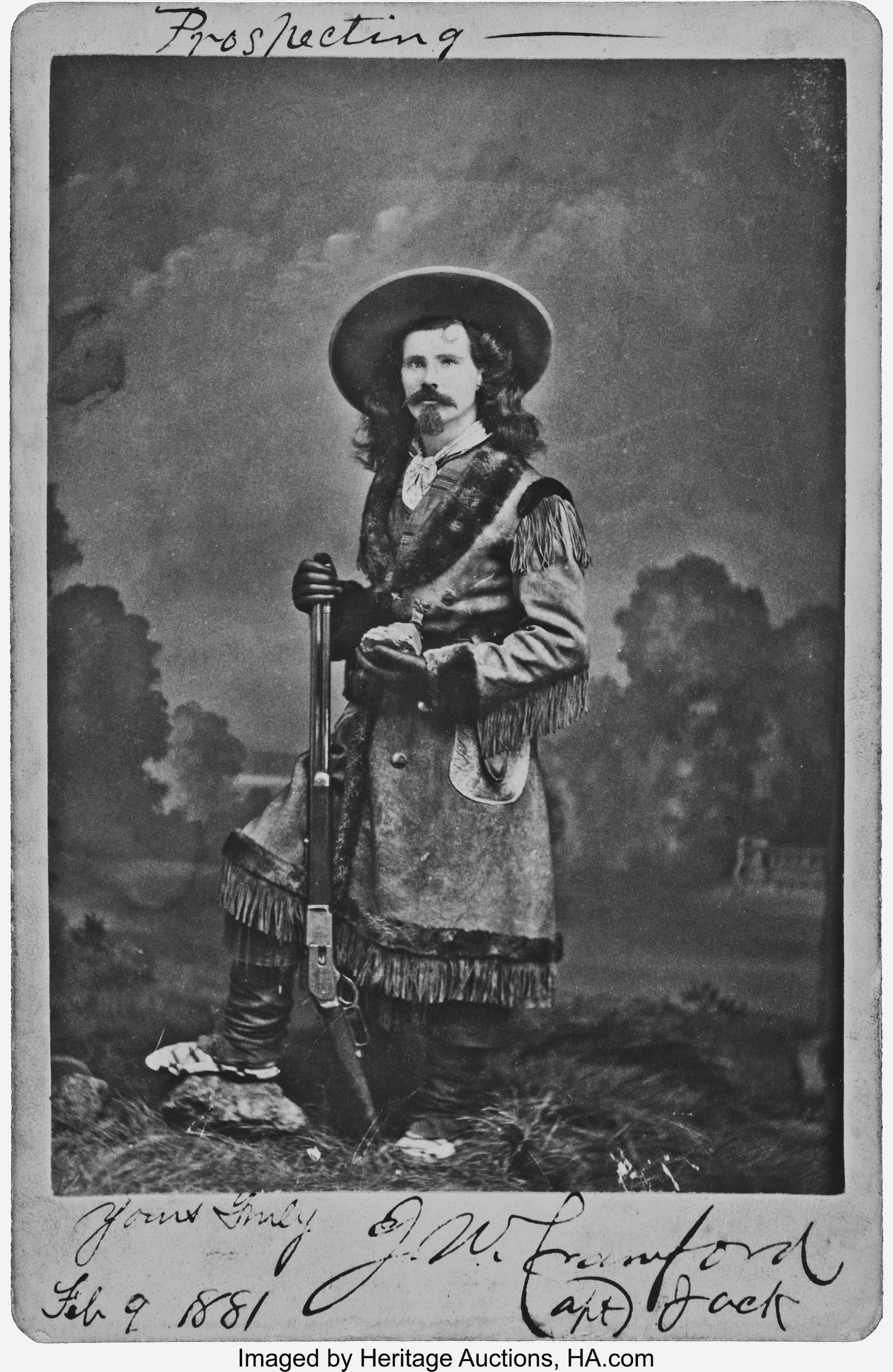

U.S. Fifth Cavalry, Crawford had worked with General George Custer19 to subdue western tribes, often by using Native telegraph signal chains (see chapter 1). After learning in a telegram from Buffalo Bill of Custer’s infamous death at the hands of local tribes at the 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn, Crawford published an ode to Custer that may have inspired Walt Whitman’s elegy of Custer, as well as the cosmic importance that this study argues, in chapter 5, Whitman attributes to Custer’s westering mission. After the Indian and Civil Wars, Crawford reenacted his role as a performer in Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show, and gained literary fame by publishing Indian-fighting stories accompanied by photos of the author in which he assumes a frontiersman persona like Custer’s, complete with Native beaded moccasins and fringed buckskin (see figure I.1). Even his adaptation of the moniker “Captain Jack” suggests his desire to inhabit an Indian identity: in the 1873 Modoc War, tribal leader Kintpuash, or Captain Jack, became the only Native during the Indian Wars officially to kill a U.S. general.

The telegraph served Crawford’s and others’ disembodied technotopias as the key to erasing the resistant bodies of America’s Native peoples, and to usurping indigenous peoples’ storied connections to American land.

As it intervenes to resolve otherwise unconquerable obstacles to characters’ erotic, Turnerian, and manifest destinies in Crawford’s “Carrie,” the telegraph acts as exactly the kind of contrived plot device against which Horace’s Ars Poetica warns: the deus ex machina. At the same time, it does so by appearing, at least within the technotopias with which this study contends, as a machina ex deo, a machine from God, sent to earth to do metaphysical and political work in the literary technotopias of nineteenth-century American authors. This invocation of the machine’s divine powers constitutes more than an aesthetic problem. I would like here to introduce a metaphysics that I will argue redounds throughout nineteenth-century understandings of telegraphy, and which serves to naturalize the competing political ambitions that often inspired the technotopias we read throughout telegraph literature.

Machina Ex Deo: Morse’s Metaphysics and the Birth of Telegraph Literature

It comes as a surprise to most modern readers, steeped as we are in common twenty-first-century antipathies between scientific and religious thought, to learn that Morse and many of his contemporaries understood most discourse conducted by signal chain not primarily through its scientific bases, but within variously inflected metaphysical, spiritual, or even biblical contexts. In fact, authors of telegraph literature seem particularly preoccupied with reconciling their technotopias with their era’s spiritual matrix, perhaps because the main

Figure I.1 John “Captain Jack” Crawford photographed in beaded moccasins and fringed buckskin. Bennet and Brown Photographers, Santa Fe, NM, 1881. Courtesy of Heritage Auction House.

ethereal realm referred to throughout the nominally pretelegraphic nineteenth century is the realm of the dead—heaven, in Western terms—that spiritual realm to which human souls relocate upon permanently leaving the body. Spirituality in telegraph literature assumes disparate stances, but beliefs about the metaphysical nature of telegraph speech seem often to ally it in writers’ minds with such alternative spiritual approaches as Unitarianism, natural theology, spiritualism, transcendentalism, older earth religions, or wholly new spiritual formulations. This desire to reconcile ideals of technologically and spiritually disembodied existence perhaps in part explains why telegraph authors so often craft for telegraphic speech decidedly romantic narratives in which the telegraph accomplishes feats of a supernatural nature, specifically conceived to fulfill God’s higher purpose. Articulating what I will refer to as a telegraph metaphysics for their virtual technotopias, telegraph writers often imagine the telegraph to provide a metaphysical conduit between the material confines of the corporeal world and the mind of God, as idealized within the often liberating, sometimes dangerous space of the virtual universe. This book seeks in part to interrogate the political and social resonances of authors’ mystic technological visions, to disclose within each its underlying, often radical reimagining of their nation’s aesthetic theory, growing empire, and rapidly changing constructions of gender and class, of ethnicity and place. This investigation helps to retool our critical conceptions of nineteenth-century American telecommunications practice and of how writers appropriated this practice to enact their metaphysical visions for a new America.20

When authors of telegraph literature crafted their resolutely political technotopias in the new metaphysical realm of virtual speech, they continued a tradition begun by Samuel Morse himself. During an early public demonstration of his machine in New York’s Washington Square, in 1838, Morse telegraphed the following cryptic message along a mile of wire to a printer that produced written Morse Code: “Attention! The Universe! By Kingdom’s Right Wheel!”

These abstruse sentence fragments seem to grant Morse’s machine a revolutionary power to command the attention of the entire universe and even to envision a talking wire that fulfills a messianic mission: according to Morse, his telegraph does nothing less than stand (as for Calvinists like Morse, Jesus stands) at the right hand of the Creator to act as the prime moving wheel of the Kingdom of God. Newspaper and historic accounts of the event roundly echo the cosmic importance that Morse’s potentially apostatic prophesies attribute to the machine. Claims one nineteenth-century biography of Morse’s Washington Square demonstration: “The work bordered upon the miraculous. ‘To see is to believe,’ but this result staggered the faith of spectators.”21 Morse’s official first telegram from 1844 quotes the Bible’s book of Numbers 23:23 to ask prophetically, “What Hath God Wrought?” With this quotation, Morse again positions