ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Thomas H. Byers is professor of management science and engineering at Stanford University and the founding faculty director of the Stanford Technology Ventures Program, which is dedicated to accelerating technology entrepreneurship education around the globe. He is the first person to hold the Entrepreneurship Professorship endowed chair in the School of Engineering at Stanford. He also is a Bass University Fellow in Undergraduate Education. He was a principal investigator and the director of the NSF’s Engineering Pathways to Innovation Center (Epicenter), which aimed to spread entrepreneurship and innovation education across all undergraduate schools. After receiving his B.S., MBA, and Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley, Dr. Byers held leadership positions in technology ventures including Symantec Corporation. His teaching awards include Stanford University’s highest honor (Gores Award) and the Gordon Prize from the National Academy of Engineering.

Richard C. Dorf is professor emeritus of electrical and computer engineering and professor of management at the University of California, Davis. He is a Fellow of the American Society for Engineering Education (ASEE) in recognition of his outstanding contributions to the society, as well as a Fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineering (IEEE). The best-selling author of Introduction to Electric Circuits (9th ed.), Modern Control Systems (13th ed.), Handbook of Electrical Engineering (4th ed.), Handbook of Engineering (2nd ed.), and Handbook of Technology Management, Dr. Dorf is cofounder of seven technology firms.

Andrew J. Nelson is associate professor of management and associate vice president for entrepreneurship and innovation at the University of Oregon. He also serves as academic director of the university’s Lundquist Center for Entrepreneurship. Dr. Nelson holds a Ph.D. and a B.A. from Stanford University, and an M.Sc. from Oxford University. Well known for his research on the emergence of new technologies, Dr. Nelson serves on the editorial boards of several leading journals and has received numerous academic awards, including recognition from the Kauffman Foundation, the Academy of Management, and INFORMS. At the University of Oregon, he is the only tenured faculty member to have received the undergraduate business, MBA and executive MBA teaching excellence awards multiple times each.

Courtesy of Thomas H. Byers

Courtesy of Richard C. Dorf

Courtesy of Andrew J. Nelson

Foreword xv

Preface xvii

PART I VENTURE OPPORTUNITY AND STRATEGY 1

Chapter 1 The Role and Promise of Entrepreneurship 3

1.1 Entrepreneurship in Context 4

1.2 Economics, Capital, and the Firm 7

1.3 Creative Destruction 11

1.4 Innovation and Technology 13

1.5 The Technology Entrepreneur 15

1.6 Spotlight on Facebook 20 1.7 Summary 21

Chapter 2 Opportunities 23

2.1 Types of Opportunities 24

2.2 Market Engagement and Design Thinking 29

2.3 Types and Sources of Innovation 34

2.4 Trends and Convergence 37

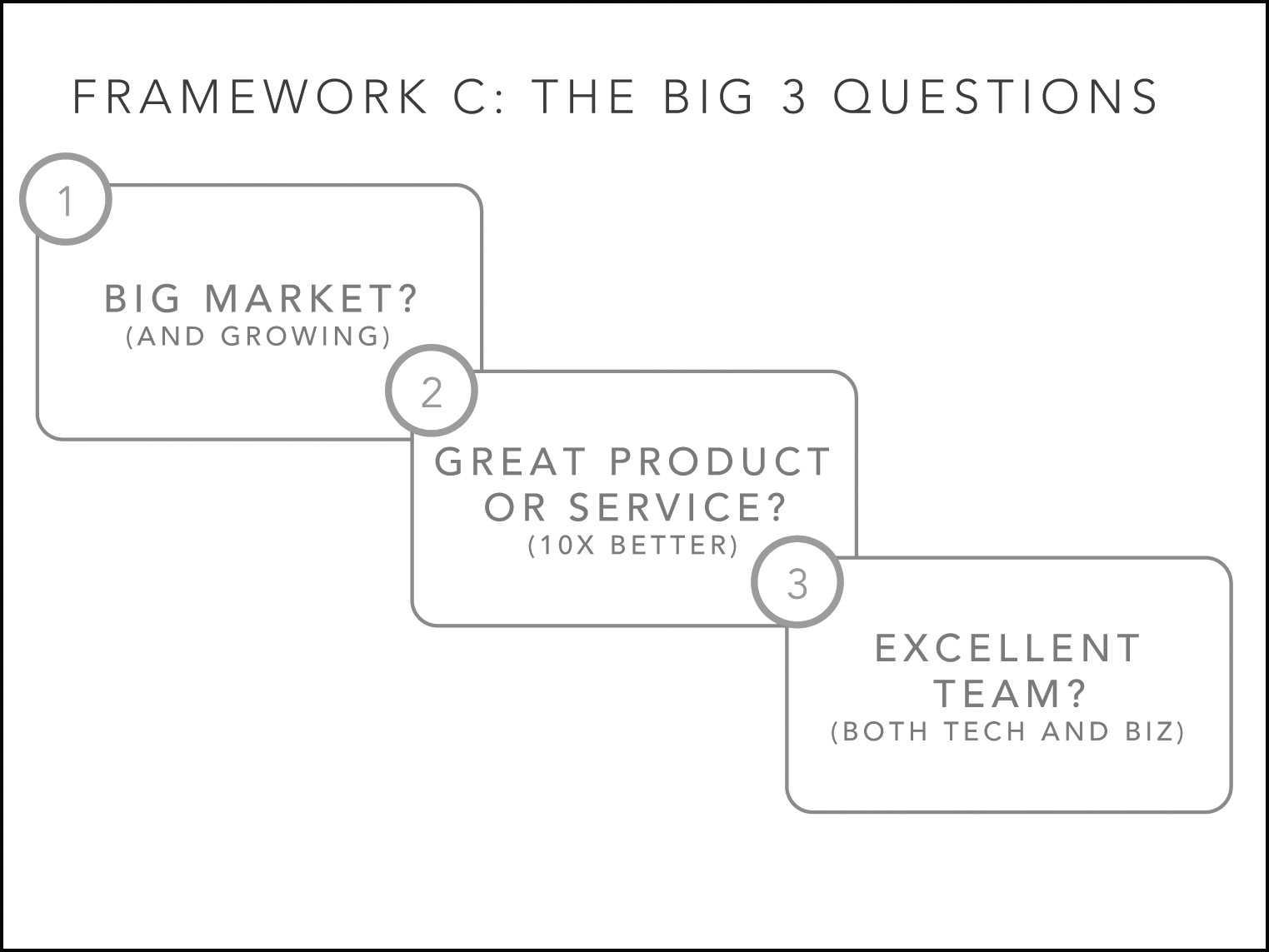

2.5 Opportunity Evaluation 40

2.6 Spotlight on Airbnb 46

2.7 Summary 47

Chapter 3 Vision and the Business Model 51

3.1 The Vision 52

3.2 The Mission Statement 53

3.3 The Value Proposition 54

3.4 The Business Model 57

3.5 Business Model Innovation in Challenging Markets 62

3.6 Spotlight on Spotify 64 3.7 Summary 64

Chapter 4 Competitive Strategy 67 4.1 Venture Strategy 68 4.2 Core Competencies 71 4.3 The Industry and Context for a Firm 72 4.4 SWOT Analysis 76 4.5 Barriers to Entry 78 4.6 Achieving a Sustainable Competitive Advantage 79 4.7 Alliances 84 4.8 Matching Tactics to Markets 88 4.9 The Socially Responsible Firm 91

4.10 Spotlight on Uber 95 4.11 Summary 95

Chapter 5 Innovation Strategies 99 5.1 First Movers versus Followers 100 5.2 Imitation 105

5.3 Technology and Innovation Strategy 106

5.4 New Technology Ventures 111

5.5 Spotlight on Alphabet 115

5.6 Summary 115

PART II CONCEPT DEVELOPMENT AND VENTURE FORMATION 119

Chapter 6

The Business Story and Plan 121

6.1 Creating a New Business 122

6.2 The Concept Summary and Story 123

6.3 The Business Plan 127

6.4 The Elevator Pitch 130

6.5 An Annotated Table of Contents 131

6.6 Spotlight on Amazon 135

6.7 Summary 135

Chapter 7 Risk and Return 139

7.1 Risk and Uncertainty 140

7.2 Scale and Scope 148

7.3 Network Effects and Increasing Returns 152

7.4 Risk versus Return 157

7.5 Managing Risk 158

7.6 Spotlight on Dropbox 159

7.7 Summary 159

Chapter 8 Creativity and Product Development 163

8.1 Creativity and Invention 164

8.2 Product Design and Development 169

8.3 Product Prototypes 175

8.4 Scenarios 178

8.5 Spotlight on Teva Pharmaceuticals 180 8.6 Summary 180

Chapter 9

Marketing and Sales 183

9.1 Marketing 184

9.2 Marketing Objectives and Customer Target Segments 185

9.3 Product and Offering Description 187

9.4 Brand Equity 189

9.5 Marketing Mix 190

9.6 Social Media and Marketing Analytics 195

9.7 Customer Relationship Management 197

9.8 Diffusion of Technology and Innovations 199

9.9 Crossing the Chasm 202

9.10 Personal Selling and the Sales Force 205

9.11 Spotlight on Snap Inc. 208

9.12 Summary 208

Chapter 10 Types of Ventures 211

10.1 Legal Form of the Firm 212

10.2 Independent versus Corporate Ventures 215

10.3 Nonprofit and Social Ventures 217

10.4 Corporate New Ventures 221

10.5 The Innovator’s Dilemma 226

10.6 Incentives for Corporate Entrepreneurs 227

10.7 Building and Managing Corporate Ventures 229

10.8 Spotlight on OpenAg 235

10.9 Summary 235

PART III INTELLECTUAL

PROPERTY, ORGANIZATIONS, AND OPERATIONS 239

Chapter 11

Intellectual Property 241

11.1 Protecting Intellectual Property 242

11.2 Trade Secrets 243

11.3 Patents 244

11.4 Trademarks and Naming the Venture 247

11.5 Copyrights 249

11.6 Licensing and University Technology Transfer 249

11.7 Spotlight on Apple 251

11.8 Summary 251

Chapter 12

The New Enterprise Organization 255

12.1 The New Enterprise Team 256

12.2 Organizational Design 260

12.3 Leadership 263

12.4 Management 267

12.5 Recruiting and Retention 269

12.6 Organizational Culture and Social Capital 272

12.7 Managing Knowledge Assets 277

12.8 Learning Organizations 279

12.9 Spotlight on Intuit 284

12.10 Summary 284

Chapter 13

Acquiring and Organizing Resources 287

13.1 Acquiring Resources and Capabilities 288

13.2 Influence and Persuasion 290

13.3 Location and Cluster Dynamics 292

13.4 Vertical Integration and Outsourcing 295

13.5 Innovation and Virtual Organizations 298

13.6 Acquiring Technology and Knowledge 299

13.7 Spotlight on NVIDIA 301

13.8 Summary 302

Chapter 14

Management of Operations 305

14.1 The Value Chain 306 14.2 Processes and Operations Management 308 14.3 The Value Web 313

14.4 Digital Technologies and Operations 317 14.5 Strategic Control and Operations 319 14.6 Spotlight on Samsung 322 14.7 Summary 322

Chapter 15 Acquisitions and Global Expansion 325

15.1 Acquisitions and the Quest for Synergy 326

15.2 Acquisitions as a Growth Strategy 328

15.3 Global Business 333

15.4 Spotlight on Alibaba 339

15.5 Summary 339

PART IV FINANCING AND LEADING THE ENTERPRISE 343

Chapter 16 Profit and Harvest 345

16.1 The Revenue Model 346

16.2 The Cost Model 347

16.3 The Profit Model 348

16.4 Managing Revenue Growth 352

16.5 The Harvest Plan 359

16.6 Exit and Failure 361

16.7 Spotlight on Tencent 362

16.8 Summary 363

Chapter 17

The Financial Plan 365

17.1 Building a Financial Plan 366

17.2 Sales Projections 368

17.3 Costs Forecast 370

17.4 Income Statement 371

17.5 Cash Flow Statement 374

17.6 Balance Sheet 375

17.7 Results for a Pessimistic Growth Rate 375

17.8 Breakeven Analysis 378

17.9 Measures of Profitability 383

17.10 Spotlight on DeepMind 384

17.11 Summary 385

Chapter 18

Sources of Capital 389

18.1 Financing the New Venture 390

18.2 Venture Investments as Real Options 392

18.3 Sources and Types of Capital 395

18.4 Bootstrapping and Crowdfunding 398

18.5 Debt Financing and Grants 401

18.6 Angels 402

18.7 Venture Capital 404

18.8 Corporate Venture Capital 409

18.9 Valuation 411

18.10 Initial Public Offering 415

18.11 Spotlight on Tesla 429

18.12 Summary 429

Chapter 19

Deal Presentations and Negotiations 433

19.1 The Presentation 434

19.2 Critical Issues 436

19.3 Negotiations and Relationships 438

19.4 Term Sheets 440

19.5 Spotlight on Circle 441

19.6 Summary 442

Chapter 20

Leading Ventures to Success 445

20.1 Execution 446

20.2 Stages of an Enterprise 449

20.3 The Adaptive Enterprise 456

20.4 Ethics 460

20.5 Spotlight on Netflix 464

20.6 Summary 464

References 467

Appendices

A. Sample Business Model 487

Homepro Business Model 488

B. Cases 503

Method: Entrepreneurial Innovation, Health, Environment, and Sustainable Business Design 504

Method Products: Sustainability

Innovation As Entrepreneurial Strategy 511

Biodiesel Incorporated 524

Barbara’s Options 528

Gusto: Scaling A Culture 532

Glossary 535

Index 544

by John L. Hennessy, President Emeritus of Stanford University

I am delighted to introduce this book on technology entrepreneurship by Professors Byers, Dorf, and Nelson. Technology and similar high-growth enterprises play a key role in the development of the global economy and offer many young entrepreneurs a chance to realize their dreams.

Unfortunately, there have been few complete and analytical books on technology entrepreneurship. Professors Byers, Dorf, and Nelson bring years of experience in teaching and direct background as entrepreneurs to this book, and it shows. Their connections and involvement with start-ups—ranging from established companies like Facebook and Genentech to new ventures delivering their first products—add real-world insights and relevance.

One of the most impressive aspects of this book is its broad coverage of the challenges involved in technology entrepreneurship. Part I talks about the core issues around deciding to pursue an entrepreneurial vision and the characteristics vital to success. Key topics include building and maintaining a competitive advantage and market timing. As recent history has shown, it is easy to lose sight of these principles. Although market trends in technology are ever shifting, entrepreneurs are rewarded when they maintain a consistent focus on having a sustainable advantage, creating a significant barrier to entry, and leading when both the market and the technology are ready. The material in these chapters will help entrepreneurs and investors respond in an informed and thoughtful manner.

Part II examines the major strategic decisions with which every entrepreneur grapples: how to balance risk and return, what entrepreneurial structure to pursue, and how to develop innovative products and services for the right users and customers. It is not uncommon for start-ups led by a technologist to question the role of sales and marketing. Sometimes, you hear a remark like: “We have great technology and that will bring us customers; nothing else matters!” But without sales, there is no revenue, and without marketing, sales will be diminished. It is important to understand these vital aspects of any successful business. These are challenges faced by every company, and the leadership in any organization must regularly examine them.

Part III discusses operational and organizational issues as well as the vital topic in technology-intensive enterprises of intellectual property. Similar matters of building the organization, thinking about acquisitions, and managing operations are also critical. If you fail to address them, it will not matter how good your technology is.

Finally, Part IV talks about putting together a solid financial plan for the enterprise including exit and funding strategies. Such topics are crucial, and they are often the dominant topics of “how-to” books on entrepreneurship. While the

financing and the choice of investors are key, unless the challenges discussed in the preceding sections are overcome, it is unlikely that a new venture, even if well financed, will be successful.

In looking through this book, my reaction was, “I wish I had read a book like this before I started my first company (MIPS Technologies in 1984).” Unfortunately, I had to learn much of this in real-time, often making mistakes on the first attempt. In my experience, the challenges discussed in the earlier sections are the real minefields. Yes, it is helpful to know how to negotiate a good deal and to structure the right mix of financing sources, especially so employees can retain as much equity as possible. However, if you fail to create a sustainable advantage or lack a solid sales and marketing plan, the employees’ equity will not be worth much.

Those of us who work at Stanford and live near Silicon Valley are in the heartland of technology entrepreneurship. We see firsthand the tenacity and intelligence of some of the world’s most innovative entrepreneurs. With this book, many others will have the opportunity to tap into this experience. Exposure to the extensive and deep insights of Professors Byers, Dorf, and Nelson will help build tomorrow’s enterprises and business leaders.

Entrepreneurship is a vital source of change in all facets of society, empowering individuals to seek opportunities where others see insurmountable problems. For the past century, entrepreneurs have created many great enterprises that subsequently led to job creation, improved productivity, increased prosperity, and a higher quality of life. Entrepreneurship is now playing a vital role in finding solutions to the huge challenges facing civilization, including health, communications, security, infrastructure, education, energy, and the environment.

Many books have been written to help educate others about entrepreneurship. Our textbook was the first to thoroughly examine a global phenomenon known as “technology entrepreneurship.” Technology entrepreneurship is a style of business leadership that involves identifying high-potential, technology-intensive commercial opportunities, gathering resources such as talent and capital, and managing rapid growth and significant risks using principled decision-making skills. Technology ventures exploit breakthrough advancements in science and engineering to develop better products and services for customers. The leaders of technology ventures demonstrate focus, passion, and an unrelenting will to succeed.

Why is technology so important? The technology sector represents a significant portion of the economy of every industrialized nation. In the United States, more than one-third of the gross national product and about half of private-sector spending on capital goods are related to technology. It is clear that national and global economic growth depends on the health and contributions of technology enterprises.

Technology has also become ubiquitous in modern society. Note the proliferation of smartphones, personal computers, tablets, and the Internet in the past 25 years and their subsequent integration into everyday commerce and our personal lives. When we refer to “high-technology” ventures, we include information technology enterprises, biotechnology and medical businesses, energy and sustainability companies, and those service firms where technology is critical to their missions. At this time in the 21st century, many technologies show tremendous promise, including computational systems, Internet advancements, mobile communications platforms, networks and sensors, medical devices and biotechnology, artificial intelligence, robotics, 3D manufacturing, nanotechnology, and clean energy. The intersection of these technologies may indeed enable the most promising opportunities.

The drive to understand technology venturing has frequently been associated with boom times. Certainly, the often-dramatic fluctuations of economic cycles can foster periods of extreme optimism as well as fear with respect to entrepreneurship. However, some of the most important technology companies have been founded during recessions (e.g., Intel, Cisco, and Amgen). This book’s principles endure regardless of the state of the economy.

APPROACH

Just as entrepreneurs innovate by recombining existing ideas and concepts, we integrate the most valuable entrepreneurship and technology management theories from the world’s leading scholars to create a fresh look at entrepreneurship. We also provide an action-oriented approach to the subject through the use of examples, exercises, and lists. By striking a balance between theory and practice, our readers gain from both perspectives.

Our comprehensive collection of concepts and applications provides the tools necessary for success in starting and growing a technology enterprise. Throughout the book, we use the term enterprise interchangeably with venture, business, startup, and firm. We show the critical differences between scientific ideas and true business opportunities for these organizations. Readers benefit from the book’s integrated set of cases, examples, business plans, and recommended sources for more information.

We illustrate the book’s concepts with examples from the early stages of technology enterprises (e.g., Apple, Google, and Genentech) and traditional ones that execute technology-intensive strategies (e.g., FedEx and Wal-Mart). How did they develop enterprises that have had such positive impact, sustainable performance, and longevity? In fact, the book’s major principles are applicable to any growth-oriented, high-potential venture, including high-impact nonprofit enterprises such as Conservation International and the Gates Foundation.

AUDIENCE

This book is designed for students in colleges and universities, as well as others in industry and public service, who seek to learn the essentials of technology and high-growth entrepreneurship. No prerequisite knowledge is necessary, although an understanding of basic accounting principles will prove useful.

Entrepreneurship was traditionally taught only to business majors. Because entrepreneurship education opportunities now span the entire campus, we wrote this book to be approachable by students of all majors and levels, including undergraduate, graduate, and executive education. Our primary focus is on science and engineering majors enrolled in entrepreneurship and innovation courses, but the book is also valuable to business students and others including the humanities and social sciences majors with a particular interest in high-impact ventures.

Our courses at Stanford University, the University of Oregon, and the University of California, Davis, based on this textbook regularly attract students from majors as diverse as computer science, product design, political science, economics, pre-med, electrical engineering, history, biology, and business. Although the focus is on technology entrepreneurship, these students find this material applicable to the pursuit of a wide variety of endeavors. Entrepreneurship education is a wonderful way to teach universal leadership skills, which include being comfortable with constant change, contributing to an innovative team, and demonstrating passion in any effort. Anyone can learn entrepreneurial

thinking and leadership. We particularly encourage instructors to design courses in which the students form study teams early in the term and learn to work together effectively on group assignments.

WHAT’S NEW

Based upon feedback from readers and new developments in the field of highgrowth entrepreneurship, numerous enhancements appear in this fifth edition. The latest insights from leading scholarly journals, trade books, popular blogs and press have been incorporated. In particular, Chapter 18 has been improved significantly to reflect the latest developments in venture finance. Every example in the textbook has been reviewed with many updated to reflect up-and-coming, technologyintensive ventures in multiple industries and based around the world. The special Spotlight sections highlight 10 new companies that further illustrate key insights in that chapter. Video resources have been revised to reflect recent compelling seminars distributed through Stanford’s eCorner series. Cases in Appendix B have been updated, streamlined, and augmented with the addition of Gusto.

FEATURES

The book is organized in a modular format to allow for both systematic learning and random access of the material to suit the needs of any reader seeking to learn how to grow successful technology ventures. Readers focused on business plan and model development should consider placing a higher priority on Chapters 3, 6, 9, 11, 12, and 17–19. Regardless of the immediate learning goals, the book is a handy reference and companion tool for future use. We deploy the following wide variety of methods and features to achieve this goal, and we welcome feedback and comments.

Principles and Chapter Previews—A set of 20 fundamental principles is developed and defined throughout the book. They are also compiled into one simple list following the Index. Each chapter opens with a key question and outlines its content and objectives.

Examples and Exercises—Examples of cutting-edge technologies illustrate concepts in a shaded-box format. Information technology is chosen for many examples because students are familiar with its products and services. Exercises are offered at the end of each chapter to test comprehension of the concepts.

Sequential Exercise and Spotlights—A special exercise called the “Venture Challenge” sequentially guides readers through a chapter-by-chapter formation of a new enterprise. At the end of each chapter’s narrative, a successful enterprise is profiled in a special “spotlight” section to highlight several key learnings.

Business Plans—Methods and tools for the development of a business plan are gathered into one special chapter, which includes a thoroughly

TABLE P1

Overview of cases.

Cases in appendix B Synopsis

Method A start-up contemplates a new product line

Method Products

Biodiesel

Barbara’s Options

Gusto

A product development effort runs into problems

Three founders consider an opportunity in the energy industry

A soon-to-be graduate weighs two job offers

A founding team endeavors to scale their culture

Issues

Part I: Opportunities, vision and the business model, marketing and sales

Part II: Innovation strategies, creativity, and product development

Part I: Opportunity identification and evaluation, business model

Part III and IV: Stock options, finance

Part III and IV Culture, scaling issues

annotated table of contents. A sample business model is provided in Appendix A. Links to additional business plans, models, and slide (pitch) decks are provided on the textbook’s websites.

Cases—Five comprehensive cases are included in appendix B. A short description of each case is provided in Table P1. Additional cases from Harvard Business Publishing and The Case Centre are recommended on this textbook’s McGraw-Hill websites. Cases from previous editions that are no longer included are available on the textbook’s website.

References and Glossary—References are indicated in brackets such as [Smith, 2001] and are listed as a complete set in the back of the book. This is followed by a comprehensive glossary.

Chapter Sequence—The chapter sequence represents our best effort to organize the material in a format that can be used in various types of entrepreneurship courses. The chapters follow the four-part layout shown in Figure P1. Courses focused on creating business plans and models can reorder the chapters with and emphasis on Chapters 3, 6, 9, 11, 12, 17, 18, and 19.

Video Clips—A collection of suggested videos from world-class entrepreneurs, investors, and teachers is listed at the end of each chapter and provided on this textbook’s websites. More free videos clips and podcasts are available at Stanford’s Entrepreneurship Corner website (see http://ecorner.stanford.edu).

Websites and Social Networking—Please visit websites for this book at both McGraw-Hill Higher Education (http//www.mhhe.com/byersdorf) and Stanford University (http://techventures.stanford.edu) for supplemental information applicable to educators, students, and professionals. For example, complete syllabi for introductory courses on entrepreneurship are provided for instructors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many people have made this book possible. Our wonderful research assistants and special advisors affiliated with Stanford University were Kim Chang, Stephanie Glass, Liam Kinney, Trevor Loy, Emily Ma, and Rahul Singireddy. Our excellent editors at McGraw-Hill were Tina Bower and Tomm Scaife. We thank all of them for their insights and dedication. We also thank the McGraw-Hill production and marketing teams for their diligent efforts. Many other colleagues at Stanford University and the University of Oregon were helpful in numerous ways, including the Stanford students who kindly supplied their sample business model for Appendix A. We are indebted to them for all of their great ideas and support. Lastly, we remain grateful for the continued support of educators, students, and other readers around the globe.

Thomas H. Byers, Stanford University, tbyers@stanford.edu

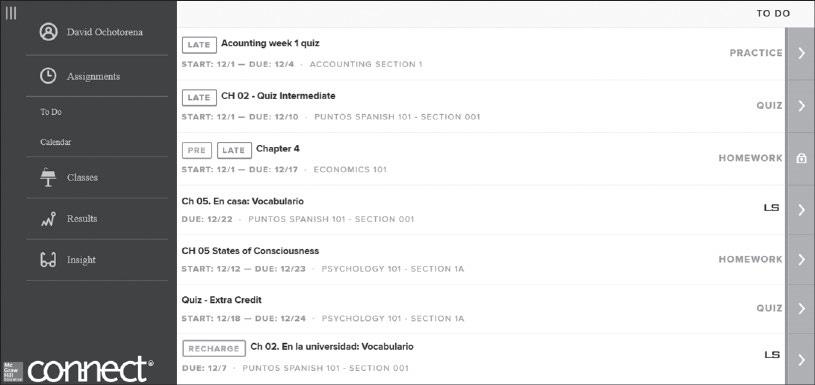

McGraw-Hill Connect® is a highly reliable, easy-touse homework and learning management solution that utilizes learning science and award-winning adaptive tools to improve student results.

Homework and Adaptive Learning

▪ Connect’s assignments help students contextualize what they’ve learned through application, so they can better understand the material and think critically.

▪ Connect will create a personalized study path customized to individual student needs through SmartBook®.

▪ SmartBook helps students study more efficiently by delivering an interactive reading experience through adaptive highlighting and review.

Over 7 billion questions have been answered, making McGraw-Hill Education products more intelligent, reliable, and precise.

Quality Content and Learning Resources

▪ Connect content is authored by the world’s best subject matter experts, and is available to your class through a simple and intuitive interface.

▪ The Connect eBook makes it easy for students to access their reading material on smartphones and tablets. They can study on the go and don’t need internet access to use the eBook as a reference, with full functionality.

▪ Multimedia content such as videos, simulations, and games drive student engagement and critical thinking skills.

Using Connect improves retention rates by 19.8 percentage points, passing rates by 12.7 percentage points, and exam scores by 9.1 percentage points.

73% of instructors who use Connect require it; instructor satisfaction increases by 28% when Connect is required.

The Role and Promise of Entrepreneurship

Strive not to be a success, but rather to be of value. Albert Einstein

Entrepreneurs strive to make a difference in our world and to contribute to its betterment. They identify opportunities, mobilize resources, and relentlessly execute on their visions. In this chapter, we describe how entrepreneurs act to create new enterprises. We identify firms as key structures in the economy and the role of entrepreneurship as the engine of economic growth. New technologies form the basis of many important ventures where scientists and engineers combine their technical knowledge with sound business practices to foster innovation. Entrepreneurs are the critical people at the center of all of these activities. ■

1.1 Entrepreneurship in Context

From environmental sustainability to security, from information management to health care, from transportation to communication, the opportunities for people to create a significant positive impact in today’s world are enormous. Entrepreneurs are people who identify and pursue solutions among problems, possibilities among needs, and opportunities among challenges.

Entrepreneurship is more than the creation of a business and the wealth associated with it. It is the opportunity to create value and the willingness to take a risk to capitalize on that opportunity [Hagel, 2016]. Entrepreneurs can launch great and reputable firms that exhibit performance, leadership, and longevity. In Table 1.1, look at the examples of successful entrepreneurs and the enterprises they created. What contributions have these people and organizations made?

TABLE 1.1 Selected entrepreneurs and the enterprises they started.

What organization would you add to the list? What organization do you wish you had created or been a part of during its formative years? What organization might you create in the future?

Entrepreneurs seek to achieve a certain goal by starting an organization that will address the needs of society and the marketplace. They are prepared to respond to challenges, to overcome obstacles, and to build an enterprise.

For an entrepreneur, a challenge is a call to respond to a difficult task and to make the commitment to undertake the required enterprise. Richard Branson, the creator of Virgin Group, reported [Garrett, 1992]: “Ever since I was a teenager, if something was a challenge, I did it and learned it. That’s what interests me about life—setting myself tests and trying to prove that I can do it.”

Thus, entrepreneurs are resilient people who pounce on challenging problems, determined to find a solution. They combine important capabilities and skills with interests, passions, and commitment. In 2004, Elon Musk realized that environmental sustainability was not a priority for the car industry, and that legacy car manufacturers were reticent to make the investments necessary to develop electric cars. He founded Tesla with the mission to introduce a highperformance, mostly electric car. Musk raised financial capital by drawing on his connections in Silicon Valley to start a paid waiting list for the company’s first model, the Tesla Roadster. Tesla was late to deliver and, in 2007, Silicon Valley blog Valleywag named the Roadster its “#1 Tech Company Fail of the Year.” That negative media attention, combined with a declining economy that heavily impacted the automotive industry, caused many of Tesla’s investments to dry up. In 2008, Musk invested his own money into the company and pleaded with investors to match him. Tesla released the Roadster that year and subsequently raised another round of funding. In 2012, Tesla released the Model S sedan, which became the best-selling plug-in electric car of 2015. In 2018, Tesla released the Model 3, with a price comparable to that of other nonelectric sedans. Musk's ability to identify an opportunity within a challenge and resilience to push through adversity have allowed Tesla to make significant progress toward achieving sustainability, both environmentally and financially.

Musk and other entrepreneurs identify the direction of needs in society and, drawing upon available knowledge and resources, respond with a plan for change. This typically involves recombining people, concepts, and technologies into an original solution. In the case of the Roadster, Tesla partnered with existing companies such as Lotus to leverage their knowledge of car design and powertrains, developed their own in-house technology where needed, and matched the final product to a network of Silicon Valley investors. Musk matched his passions and resources to capitalize on an opportunity.

An opportunity is a favorable juncture of circumstances with a good chance for success or progress. Attractive opportunities combine good timing with realistic solutions that address important problems in favorable contexts. It is the job of the entrepreneur to locate new ideas, to determine whether they are actual opportunities, and, if so, to put them into action. Thus, entrepreneurship may be described as the nexus of enterprising individuals and promising opportunities

Interest, passions, and commitment

∙ Enjoys the tasks

∙ Enjoys the challenge

∙ Committed to do what is necessary

Attractive opportunity

∙ Timely

∙ Solvable

∙ Important

∙ Profitable

∙ Favorable context

sweet spot

Capabilities and skills

∙ Good at the needed tasks

∙ Willingness to learn

1.1 Selecting the right opportunity by finding the sweet spot.

[Shane and Venkataraman, 2000]. As illustrated in Figure 1.1, the “sweet spot” exists where an individual’s or team’s passions and capabilities intersect with an attractive opportunity.

Entrepreneurship is not easy. Only about one-third of new ventures survive their first three years. As change agents, entrepreneurs must be willing to accept failure as a potential outcome of their venture. But, a person can learn to act as an entrepreneur, and can minimize the downside of failure, by trying the activity in a low-cost manner.

After identifying a problem and a proposed solution, the first step is to recognize the hypotheses associated with an idea: What assumptions is the entrepreneur making when concluding that an identified problem is really a problem and that a proposed solution is good and realistic? Then, the entrepreneur can test these hypotheses by engaging with knowledgeable individuals, such as potential customers, employees, and partners. Through these small experiments, the entrepreneur not only develops contacts and mentors critical for executing upon an idea [Baer, 2012], but also learns more about the opportunity, and what changes

FIGURE

TABLE 1.2 Four steps to starting a business.

1. The founding team or individual has the necessary skills or acquires them.

2. The team members identify the opportunity that attracts them and matches their skills. They create a solution to match the opportunity.

3. They acquire (or possess) the financial and physical resources necessary to launch the business by locating investors and partners.

4. They complete an arrangement or contract with their partners, with investors, and within the founder team to launch the business and share the ownership and wealth created.

may be necessary to make it viable. In this way, entrepreneurship is akin to the scientific method, in that entrepreneurs seek to gather data in connection with hypotheses, and they refine their ideas based upon their findings [Sarasvathy and Venkataraman, 2011]. Put simply, as Y Combinator founder Paul Graham advises, there are three key things necessary to creating a successful startup: start with good people, make something that people actually want and are willing to pay for, and spend as little money as possible while you validate the market and your product acceptance by buyers [Graham, 2005].

If team members identify an opportunity that attracts them and matches their skills, they next obtain the resources necessary to implement their solution. Finally, they launch and grow an organization, which can grow to have a massive impact, like those enterprises listed in Table 1.1. The four steps to starting a business appear in Table 1.2. Most entrepreneurs repeat these steps multiple times as they work to validate an opportunity, making continual adjustments as they learn more. Ultimately, entrepreneurship is focused on the identification and exploitation of previously unexploited opportunities. Fortunately for the reader, successful entrepreneurs do not possess a rare entrepreneurial gene. Entrepreneurship is a systematic, organized, rigorous discipline that can be learned and mastered [Drucker, 2014]. This textbook describes how to identify true business opportunities and how to start and grow a high-impact enterprise.

1.2 Economics, Capital, and the Firm

All entrepreneurs are workers in the world of economics and business. Economics is the study of the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. Society, operating at its best, works through entrepreneurs to effectively manage its material, environmental, and human resources to achieve widespread prosperity. An abundance of material and social goods equitably distributed is the goal of most social systems. Entrepreneurs are the people who arrange novel organizations or solutions to social and economic problems. They are the people who make our economic system thrive [Baumol et al., 2007]. According to Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) researchers, the United States maintained about a 12 percent entrepreneurial activity rate between 1999 and 2015. Thus, more than one in ten U.S. adults was engaged in setting up or managing a new enterprise during that period [Kelley et al., 2016].