https://ebookmass.com/product/taking-stock-of-shock-socialconsequences-of-the-1989-revolutions-ghodsee/

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

The Economics of the Stock Market Andrew. Smithers

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-economics-of-the-stock-marketandrew-smithers/

ebookmass.com

The Problem of Property: Taking the Freedom of Nonowners Seriously Karl Widerquist

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-problem-of-property-taking-thefreedom-of-nonowners-seriously-karl-widerquist/

ebookmass.com

Paths of Development in the Southern Cone: Deindustrialization and Reprimarization and their Social and Environmental Consequences Paul Cooney

https://ebookmass.com/product/paths-of-development-in-the-southerncone-deindustrialization-and-reprimarization-and-their-social-andenvironmental-consequences-paul-cooney/ ebookmass.com

The ADA Practical Guide to Dental Implants 1st Edition

Luigi O. Massa

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-ada-practical-guide-to-dentalimplants-1st-edition-luigi-o-massa/

ebookmass.com

Fundamentals of Logic Design, Enhanced Edition Jr.

Charles H. Roth

https://ebookmass.com/product/fundamentals-of-logic-design-enhancededition-jr-charles-h-roth/ ebookmass.com

Anti-Catholicism in Britain and Ireland, 1600–2000: Practices, Representations and Ideas 1st ed. Edition Claire Gheeraert-Graffeuille

https://ebookmass.com/product/anti-catholicism-in-britain-andireland-1600-2000-practices-representations-and-ideas-1st-ed-editionclaire-gheeraert-graffeuille/ ebookmass.com

Master Handbook of Acoustics, 7th Edition F. Alton Everest

https://ebookmass.com/product/master-handbook-of-acoustics-7thedition-f-alton-everest/

ebookmass.com

A Festival of Mathematics: A Sourcebook 1st Edition Alice Peters

https://ebookmass.com/product/a-festival-of-mathematics-asourcebook-1st-edition-alice-peters/

ebookmass.com

Digital Marketing Strategies for Value Co-creation : Models and Approaches for Online Brand Communities Wilson Ozuem

https://ebookmass.com/product/digital-marketing-strategies-for-valueco-creation-models-and-approaches-for-online-brand-communities-wilsonozuem/

ebookmass.com

The Preface: American Authorship in the Twentieth Century

Ross K. Tangedal

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-preface-american-authorship-in-thetwentieth-century-ross-k-tangedal/

ebookmass.com

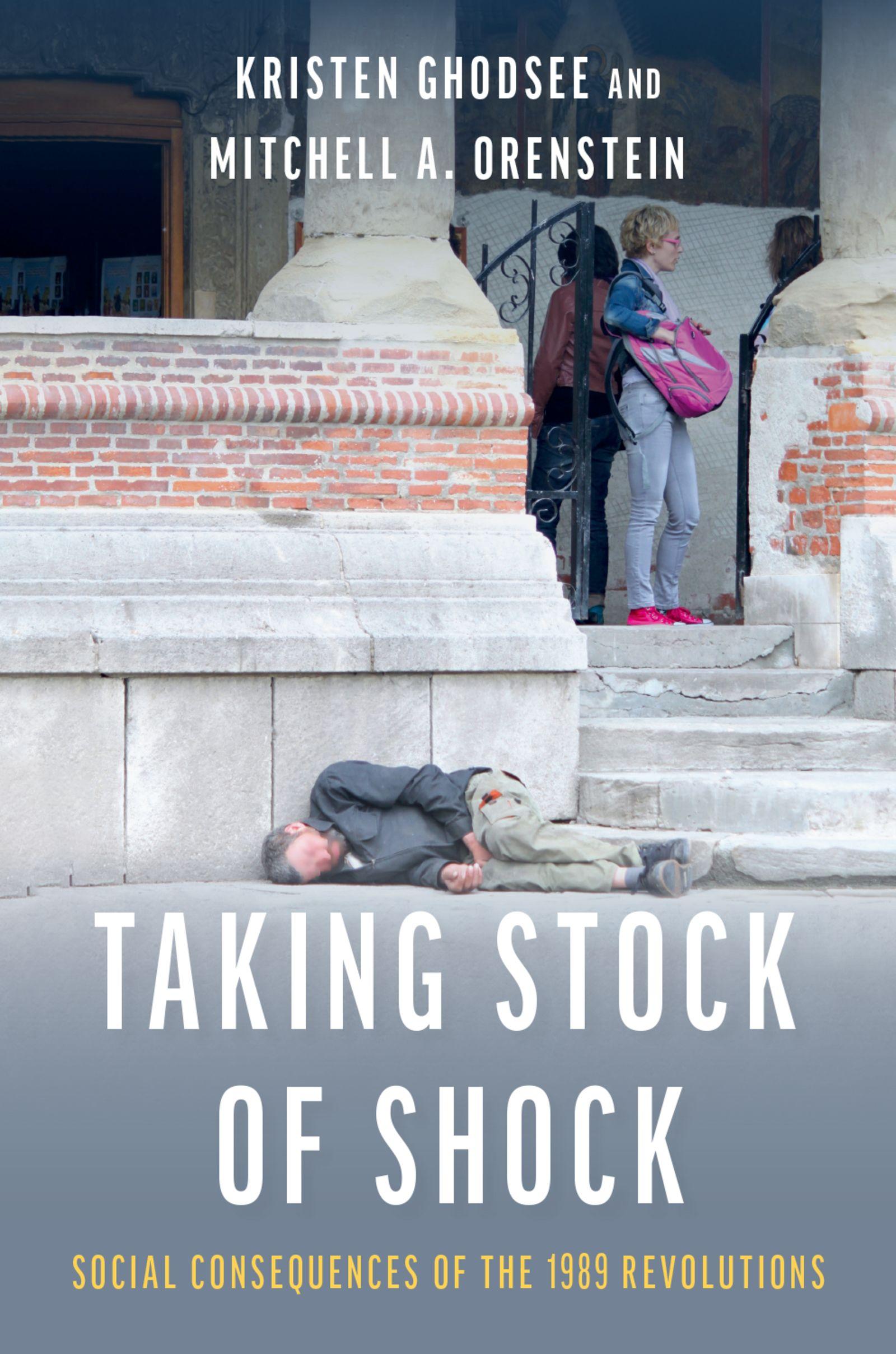

Taking Stock of Shock

Social Consequences of the 1989 Revolutions z

KRISTEN GHODSEE

AND

MITCHELL A. ORENSTEIN

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ghodsee, Kristen Rogheh, 1970– author. | Orenstein, Mitchell A. (Mitchell Alexander), author. Title: Taking stock of shock : social consequences of the 1989 revolutions / Kristen Ghodsee and Mitchell A. Orenstein.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2021000852 (print) | LCCN 2021000853 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197549230 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197549247 (paperback) | ISBN 9780197549261 (epub) | ISBN 9780197549278 (digital online)

Subjects: LCSH: Europe, Central—Economic conditions—1989– | Europe, Eastern—Economic conditions—1989– | Asia, Central—Economic conditions—1991– | Former communist countries—Economic conditions.

Classification: LCC HC244 .G495 2021 (print) | LCC HC244 (ebook) | DDC 330.943/0009049—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021000852

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021000853

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197549230.001.0001

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Paperback printed by Marquis, Canada

Hardback printed by Bridgeport National Bindery, Inc., United States of America

For our children and other members of Generation Z who started university in the midst of a pandemic. May the shocks to come not limit your horizons.

2.1

2.2

4.1

5.1

Authors’ Note on Terminology

Anyone writing an interdisciplinary book that includes perspectives and data from economics, political science, sociology, demography, and cultural anthropology will inevitably encounter disagreements about terminology. Different disciplinary traditions have specific vocabularies, and the same term can acquire vastly different meanings across scholarly contexts. In this prefatory note, we try to address a few of the most contested terms and concepts as they are used in this book.

In the discipline of political science, it is common to refer to the countries of Eastern Europe that once had planned economies and authoritarian rule as “communist” countries, because these countries were led by communist parties (the Bulgarian Communist Party, the Romanian Communist Party, etc.) that often referred to themselves as “communists.” These communists, however, called the political and economic system of their countries “socialism” or “realexisting socialism” because in Marx’s historical materialist view, socialism was a stage on the way to communism (when the state would eventually wither away). Communism was their ultimate goal, but they recognized that they were stuck in the “dictatorship of the proletariat” stage of socialism. In anthropology and history, therefore, these countries tend to be referred to as “socialist” or “state socialist” (to differentiate them from the “democratic socialist” or “social democratic” countries of Scandinavia). When referring to the period after 1989 or 1991, different disciplines call these countries “postcommunist” and “postsocialist,” and scholars and citizens in the region use these terms interchangeably. Some scholars, activists, and policymakers prefer to use the terms “communism” and “postcommunism” to refer to the twentieth-century experiments with Marxist ideology so they can differentiate those experiences from the contemporary salience or potential future for something called “socialism” or “democratic socialism.” Others prefer to call these societies “socialist,” because that is what they called themselves. In this book, we use these terms interchangeably, particularly when quoting from different scholarly sources that use the terms in different ways. This

will inevitably cause some confusion for the reader, but we want to make it clear that as authors we are trying to respect the terminologies of different disciplines without making political judgments.

Similarly, anthropologists have critiqued the term “transition” to refer to the changes in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia following 1989–91 because it implies the inevitability of an endpoint of multi-party democracy and capitalism. Some scholars preferred the term “transformation” because it kept open the possibility that these countries might transform into different forms of authoritarianism or even return to some kind of feudalism before they embraced parliamentary democracy. Moreover, the term “transformation” recognizes that the transition to a functioning market economy might not happen at all, and instead these countries might transform into oligarchies or dysfunctional state kleptocracies. Despite these nuances, we favor the term “transition” because it is the term used most frequently by international financial institutions, Western politicians, and policymakers as well as by politicians and policymakers in the region.

We are also well aware of the ongoing debates about whether we should still be using the “transition” paradigm and whether these countries should be pigeonholed as postsocialist or postcommunist, since the socialist era only represented a small fraction of their histories. Chari and Verdery argue that we should be talking of a shared global “post– Cold War” history, since the term “postsocialist” ghettoizes Eastern Europe and prevents a shared analysis with those working in the post-colonial context.1 While acknowledging problems of continuing to use the “post-” prefix for a political and economic reality that ended over three decades ago, we believe that the postsocialist framework remains relevant because of the unique shared experience of dismantling centrally planned state-owned economies and their sudden insertion into a global capitalist economy that produced distinct classes of winners and losers.

Finally, many scholars have resisted the formulation of “Eastern Europe and Central Asia” as a coherent region, insisting that these countries have centuries of history, and charge that it is intellectually imperialist of Western scholars and policymakers to define them by a mere four to seven decades of their recent history. While we are both sensitive to and cognizant of this critique, we persist with this framework because we are specifically interested in examining the social impacts of the transition/transformation of these societies after 1989–91 when they entered (or were forced to enter) the global capitalist economy. More important, economists and policymakers still consider this region as some kind of coherent whole and are deeply invested in ensuring that the transition from communism to capitalism is perceived to be a historical success, thanks to the advice of Western experts working in concert with local elites. Anthropologists,

architects, and urban planners also tend to see important similarities in the postsocialist cultures, physical structures, and built environments of the region, examining the affective and material legacies of the shared socialist past. We therefore adopt this conception of the region in part to engage with these claims on their own terms.

The attempt to write a book across so many disciplinary boundaries and engage with the frameworks proposed and propagated by international financial institutions requires that we adopt some terminologies that we ourselves might find problematic. We accept that scholars and policymakers from different backgrounds might find issues with the way we label different concepts, or question the relevance of the concepts themselves, but we sincerely hope that these largely semantic differences can be overcome for the sake of creating a robust interdisciplinary conversation about the social impacts of the events of the last three decades in Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

Introduction

Transition from Communism— Qualified Success or Utter Catastrophe?

If you had traveled to Prague, Sofia, Warsaw, Dushanbe, Kiev, Baku, or Bucharest in 2019, you would have found glittering new shopping malls filled with imported consumer goods: perfumes from France, fashion from Italy, and wristwatches from Switzerland. At the local Cineplex, urbane young citizens queued for the latest Marvel blockbuster movie wearing the trendiest Western footwear. They stared intently at their smart phones, perhaps planning their next holiday to Paris, Goa, or Buenos Aires. Outside or below ground, their polished Audis, Renaults, or Suzukis were parked in neat rows, guarded by vigilant attendants. The center of the city was crammed with hotels, cafes, and bars catering to foreigners and local elites who bought their groceries at massive German and French hypermarkets selling over fifty types of cheese. Compared to the scarcity and insularity of the bleak communist past, life in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia had improved remarkably. Gone were the black markets for a pair of Levi’s jeans, a skateboard, or a pack of Kent cigarettes. Banished were the long lines for toilet paper. People could leave the country if they pleased, assuming they had the money.

In these same capital cities, often not too far from the fashionable center or in their rural and industrial hinterlands, pensioners and the poor struggled to afford even the most basic amenities. Older citizens chose between heat, medicine, and food. Unemployed youth dreamed of consumer goods and foreign vacations they could never afford. Homeless men slept haphazardly on park benches, and frail grandmothers sold handpicked flowers or homemade pickles to busy passersby. In rural areas around the country, whole families had returned to subsistence agriculture, withdrawing from the market altogether and farming their

small plots much as their ancestors did in the nineteenth century. Young people without resources fled the countryside in droves, seeking better opportunities in metropoles such as Warsaw, Moscow, and St. Petersburg or in Western Europe. Even those with resources were desperate to live in a “normal” country and often sought to further their education and employment opportunities abroad. No country was too far if the wages were higher than those at home. Faced with ongoing struggle, many women delayed childbearing, giving up hope that their countries could reform. Economic suffering and political nihilism fueled social distrust as nostalgia for the security and stability of the authoritarian past grew. New populist leaders seized this discontent to dismantle democratic institutions and undermine fair market competition.

These two worlds existed side by side. Both were born in the wake of the dramatic fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. After a decades-long ideological conflict that defined much of the twentieth century and brought the world to the brink of total nuclear annihilation, the Cold War just ended. Almost overnight, more than 400 million people found themselves in nations transitioning from state socialism and central planning to liberal democracy (in most cases) and free markets. With remarkable speed and relatively little bloodshed, the once communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia threw off the chains of authoritarianism and decided that if they couldn’t beat the West, they might as well join it.

For the most part, the world celebrated the peaceful ending of superpower rivalry. Leaders and citizens of the prosperous, colorful West imagined themselves as welcoming saviors to the tired and downtrodden masses of the poor, gray East. Celebrating access to previously inaccessible bananas and oranges, color TVs and erotic toys, leaders of the triumphant West promised prosperity and liberty. For the prize of political freedom and economic abundance, no cost seemed too high, and the initial postsocialist years were a mixture of euphoria and heightened expectations. But like the promised land of the once bright communist future, the new utopia could only be achieved by suffering through a time of great sacrifice. Privatization, price liberalization, and labor market rationalization upended a decades-long way of life behind the former Iron Curtain. Politicians and policymakers understood that there would be social costs associated with the transition to market economies, but no one knew how high they would be. And like the communist leaders before them who hoped to build a new world, no one stopped to ask how high a cost was too high a cost to pay. The social, political, and economic transformation proceeded with limited attention to the human lives that might be devastated by the process. More than three decades later—and with the benefit of hindsight—scholars are beginning to wonder about the people whose lives were upended by the process popularly known in some Eastern European

countries as “the Changes.” This book offers an interdisciplinary examination of one key question: What were the social impacts of the transition that started in 1989 in Central and Eastern Europe and in 1991 in the Soviet Union?

Without a doubt, the collapse of communism had an immense impact on both theory and practice. Communism or state socialism1 represented the most powerful alternative political-economic system to global capitalism and had a direct impact on hundreds of millions of people spread over 10,000 kilometers from Budapest in the West to Vladivostok in the Far East. Despite the massive scale of its world-historic implosion, evaluations of the transition have been sharply divided. On the one hand, some argue that the transition has been largely a success.2 Economic reforms led to a recession that lasted a few years in some countries and was more prolonged in others but eventually generated improved rates of economic growth and gains in wealth, per capita income, and life satisfaction. Advocates of this J-curve perspective—so called since the trajectory of economic production and consumption were supposed to follow a J-curve (imagine a Nike swoosh: an initial dip in GDP followed by a gradual but steady increase in the long run)—acknowledge that the transition produced some losers and even aggregate declines at the start. But the belief is that these initial losses (although severe) were more than made up for by improved economic prospects for people over the longer term. Embracing radical change was justified, despite the costs, since the speed of reform largely dictated whether gains were realized more quickly or slowly.

From the opposite point of view, some scholars and politicians portray the transition as a socioeconomic catastrophe of enormous proportions.3 Its effects have been tantamount to the Great Depression of the 1930s. People thrown out of work during the transition never recovered. Social ills grew exponentially. Prostitution and human trafficking thrived. Substance abuse exploded. Poverty deepened. Fertility and family formation plummeted. Life expectancy dropped, catastrophically in some cases. Millions of people abandoned failing states and moved abroad in search of a better life. Governance also suffered: communist institutions collapsed and were replaced not by well-governed Western ones but by corruption, criminality, and chaos. Rather than bringing long-term benefits, the transition produced gains that disproportionately went to a narrow group of people at the top of the income distribution—especially scheming oligarchs with links to organized criminal syndicates and/or former communist state security services. The rest of the population suffered serious long-term damage from which many never recovered. The transition process created a form of insidious klepto-capitalism that reduced hundreds of millions of people to relative poverty and social dislocation, especially when compared to their previous standard of living before 1989/1991.

Which of these two portraits of transition more accurately reflects reality and for whom? These questions have taken on greater salience since the global financial crisis that began in 2008, which some have dubbed the Great Recession. The fallout from Wall Street’s collapse emboldened and empowered far-right and far-left populists, who represent a public that seems disenchanted with both markets and liberal democracy. The 2020 coronavirus pandemic and planet-wide economic shutdowns have further shaken faith in the ability of democratically elected leaders to protect their citizens from public health crises and financial ruin. Opinion polls show that people want a better life and are willing to accept authoritarian governance and crony capitalism to produce jobs and economic growth at home. Since many of these politicians and parties in Eastern Europe support a negative image of the transition period, it is an important time to ask: what exactly were the social impacts of transition? Why did perceptions of it become so bifurcated? Why is there no consensus among social scientists about its results? Answering these questions will help to address the most important one of all: Can the negative aspects of transition be addressed without the complete unraveling of the system of markets and democracy that was launched in 1989/1991? And with what repercussions for the West?

It should perhaps come as no surprise that the “winners” of these processes are those most invested in promoting the idea that the shift to liberal democracy and market economy were a qualified success. All questions about the legality or fairness of transition challenge the legitimacy of their newfound wealth. On the other hand, opponents of the Western international order and “losers” of transition point to the many deficiencies of the process, including the violence and theft that characterized the 1990s. A narrative of victimization and belief in conspiracy theories allows those left behind—and those who seek to lead them in a different direction—to blame corrupt elites and foreign powers for their ongoing postsocialist woes. In her book, Second-Hand Time, Belarusian Nobel Prize–winning author Svetlana Alexievich gives eloquent voice to the Sovoks, the last of the Soviets, for those willing to listen.4 These populations cling to their nostalgia for the past, spinning tales about the good old days of state socialist stability and security. As a result, just asking the question—what were the social impacts of transition?—is a deeply political and contested question in the region and the West because different parties have conflicting vested interests in the answer.

An Interdisciplinary Perspective

Ever mindful of this larger context, our initial conversations blossomed into an interdisciplinary perspective where we combine both quantitative and qualitative data to produce a more robust picture of how transition worked in practice and

who were the main winners and losers. The reasons for this approach are simple: different social science disciplines have arrived at contradictory images of the transition process. This is largely because each discipline has employed different methods, different metrics, and different theoretical perspectives. In short, different ways of looking at the transition have produced sometimes incompatible narratives of what happened. While it may be too much to hope that one could reconcile these opposing viewpoints, we believe that we are well placed to present a more holistic view informed by the disciplines of economics, demography, political science, sociology, and anthropology.

Kristen Ghodsee is an ethnographer who has been conducting fieldwork and research in Eastern Europe for almost twenty-five years, and Mitchell Orenstein is a political scientist who has specialized in the political economy of Eastern Europe since 1990. Although our training is in different fields, we have always worked at the intersections of a number of disciplines to examine gender issues or social policy. We have collectively published fifteen books and over ninety journal articles and essays about Eastern Europe and the transition process. In addition to our academic work, we have both written for policymakers and general audiences, trying to engage the wider public in discussions about East European politics, history, and culture. In this book, we hope to provide a general overview of the state of scholarship in several key fields and synthesize it in a new way to make sense of a transition whose bifurcated understandings undermine clarity. We believe that Manichean views are the enemy of true understanding, and that a more nuanced view of the transition process will help us to see what is going on today with the hope of reaching a better tomorrow.

The J-Curve Perspective

One of the two mainstream perspectives on transition is what we call the “Jcurve” perspective.5 This perspective is popular in economics and political science and bears a close relation to early theories of transition. It is represented in journals such as Economics of Transition and embedded in international organizations such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the World Bank. In many ways, the “J-curve” perspective is the official narrative on transition, pronounced by Western governments, international organizations, think tanks, thought leaders, and their Central and East European partners. It is also the perspective most often championed by the so-called winners of the transition process and embraced by some of the economists responsible for designing transition programs. For instance, Andrei Schleifer and Daniel Treisman argued in 2014 that transition had been an undoubted success.6 World Bank economist Marcin Piatkowski claimed that “Poland, the largest economy

among post-socialist EU member states and the sixth largest economy in the European Union on the purchasing power parity basis, has just had probably the best 20 years in more than one thousand years of its history.”7

In this perspective, transition to markets and democracy in postcommunist countries was bound to be difficult. The move from communism to capitalism would entail a process of what Joseph Schumpeter called “creative destruction.”8 The old institutions and practices of communism had to be thoroughly destroyed before new capitalist enterprises and practices could be adopted. This destruction initially would create a deep transitional recession. However, the great creativity unleashed by capitalism would soon wipe out the losses and produce substantial gains. Economic growth and household consumption would dip at first, followed by long-term gains in the shape of a J-curve.

Proponents of a J- curve transition expected that economic growth and household consumption would decline and poverty would grow—for a time. How long? That was never specified exactly, but it was assumed that a few years would be an appropriate length of time. Moreover, reformers expected that the more radical and thorough the economic reforms, the faster the return to growth would be. Therefore, advocates of the J-curve did not worry too much about severe dips in household consumption. These were expected to be temporary, despite the possibility that if they lasted too long, countries could get caught in a poverty trap.9 Reformers advocated safety-net measures and unemployment insurance to prevent the worst suffering, but they also believed that transition had to happen quickly to prevent more severe long-term agony and/or a return to the planned economy. And indeed, advocates of the J-curve hypothesis still insist that this is exactly what happened.10 Countries that reformed faster and more thoroughly returned to growth quicker. Measures to slow or ameliorate this process only prolonged and magnified the pain—by making the transition recession last longer.

In terms of real-world examples, the Visegrad countries of Poland, Hungary, Czechia, and Slovakia best illustrate the workings of the J-curve transition. These countries experienced anti-communist revolutions in 1989 and began to reform their economies in 1990. Neoliberal economic reforms brought on a deep transitional recession, with per capita GDP declining by between 10 to 23 percent. But these economies bottomed out in 1992 or 1993 and soon began to grow again. By 1998–2000, the Visegrad countries had surpassed their 1989 levels of per capita gross domestic product (GDP). They grew strongly in the 2000s and by 2007 produced per capita GDP levels 40 to 66 percent higher than in 1989. From a strictly economic point of view, these countries achieved a model transition, avoiding the longer and more severe recessions of less avid reformers.

Growth picked up again in the mid-2010s following the global financial crisis. Mercedes, for instance, broke ground in 2018 on a new €1 billion car plant

in Kecskemét, Hungary, beside an existing plant where it already employed 4,000 people and produced 190,000 compact cars in 2017. In 2019, Mercedes reached a wage agreement with Hungarian trade unions to increase pay by 35 percent over a two-year period as well as other benefits, including retention incentives.11 Hungary had become one of the leading automotive producers in Europe, accounting for 29 percent of Hungarian industrial production, approximately 9 percent of its total economy, 17 percent of its exports, and 4 percent of total employment.12 Based on this and successes in many other industries from fashion to furniture, one 2019 report concluded that the Visegrad countries (plus Slovenia and the Baltics) “managed to make a transition from a socialist past to modern economies that started to reindustrialize after 1996 and subsequently made substantial progress in catching up to Western Europe in terms of GDP per capita, labour productivity and living standards.”13

For some citizens, the transition away from planned economies created a new world of exciting opportunities. The journalist John Feffer, who traveled across Eastern Europe in 1989/1990 and then returned again in 2016 to observe the changes, recounts the story of Bogdan, a man who had been a psychologist at the Polish Academy of Sciences when Feffer first met him. After 1989, Bogdan left academia, divorced his wife, and applied for a managerial position at the Swedish home-furnishing company, IKEA. Bogdan tells Feffer, “At that time, you opened a newspaper and you saw: financial director for Procter & Gamble, marketing direction for Colgate Palmolive. . . . All those companies were looking [to fill] top positions.”14 Bogdan shot up to become a member of the board of directors within a week and almost overnight became a high-level executive with a new car, a new wardrobe, and an entirely new life. He helped establish IKEA in Poland and then moved on to a lucrative career as a management consultant to other Western multinational companies hoping to do business in his country.

Bogdan is a member of what Feffer calls the “fortunate fifth,” the portion of the East European population that used the events of 1989 to reinvent their lives and seize new economic and political opportunities made possible by the coming of democracy. There is Vera, a woman who became the first Roma-Bulgarian news anchor, something that would probably have been impossible under the old regime. A new generation of dissident voices used their guaranteed free speech to attempt to keep governments accountable to the people. Newspapers and television stations proliferated. Gays and lesbians came out of the closet and enjoyed free self-expression in newly open societies with the support of the international lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) community. Consumer shortages disappeared and a cornucopia of new goods rushed in to meet decades of pent-up demand. Young people won scholarships to study at foreign universities, and professionals enjoyed new avenues for retraining in Western Europe and the United States. Feffer writes: