1

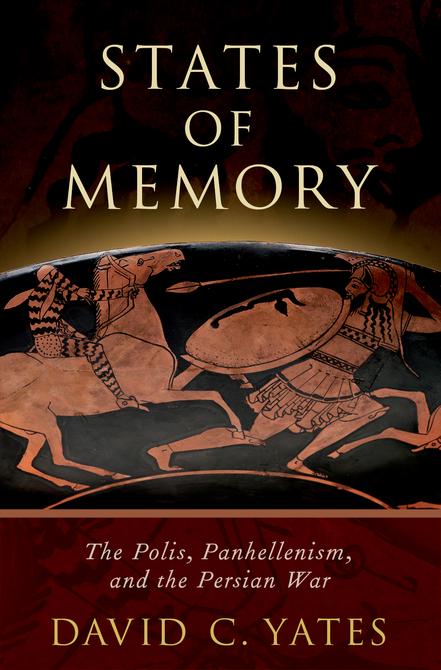

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 978–0–19–067354–3

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

For Jennifer and Lily

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments ix

List of Abbreviations xi

Note on Sources xiii

Maps xvii

Introduction: The Collective Memories of the Persian War 1

1. The Serpent Column 29

2. Panhellenism 61

3. Contestation 99

4. Time and Space 135

5. Meaning 168

6. A New Persian War 202

7. After Alexander 249

Conclusion: The Persian War from Polis to Panhellenism 267

Bibliography 275

Index Locorum 317

Index 327

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The concept behind this book emerged from a seminar on Persian-War memory taught at Brown University by Deborah Boedeker. It then became the subject of my dissertation (Remembering the Persian War Differently). Throughout its initial development and later, as I revised the dissertation for publication, I benefited from the unstinting generosity of both Deborah Boedeker and Kurt Raaflaub, who read countless drafts, shared their expertise, and offered invaluable guidance.

I am also indebted to a number of colleagues who read drafts, gave feedback, and offered advice at various stages of this project: Susan Alcock, Hans Beck, Michael Flower, Michael Galaty, Lauren Ginsberg, Peter Hunt, David Konstan, John Marincola, William Storey, and Mark Thatcher. I would like to thank Stefan Vranka of Oxford University Press and the anonymous reviewers of this book, whose candid critiques much improved the final product. Furthermore, I owe a debt of gratitude to those scholars who, though not directly involved in this project, have nevertheless had a profound impact on my own understanding of the ancient world more generally: Charles Fornara, John Gibert, Jon Lendon, and Elizabeth Meyer.

This book includes portions of my own earlier publications (Yates 2013 and 2018), which are included here with the kind permission of Hans Beck (Teiresias Supplements Online) and Hans-Joachim Gehrke (Klio). I am additionally grateful to Robert Strassler, who gave me permission to make extensive use of The Landmark Herodotus

I also want to acknowledge the support provided by Millsaps College as well as its faculty, staff, and students. The Provost, Keith Dunn, is a strong advocate for faculty research and has shown his characteristic interest in and support of my own project. I have been awarded numerous faculty grants, was allowed a pre-tenure course release, and was awarded a full-year sabbatical for 2017/18—the last through the kind generosity of an anonymous donor to the college. I also benefited from the warm encouragement of my colleagues in the Department of Greek and Roman Studies, Holly Sypniewski and Jennifer Lewton-Yates. Despite all, this book could never have come to fruition without the tireless work of the staff at the Millsaps-Wilson Library, who brought a world of scholarship on the Persian War to Jackson, Mississippi. So, a special thanks to Jamie Bounds Wilson, Tom Henderson, Jody Perkins, Elizabeth Beck, Mariah Grant, Sheila Morgan, and Molly McManus.

Acknowledgments { x

Finally, I thank my wife, Jennifer Lewton-Yates, and my daughter, Lily, who reminded me throughout the long process of writing that in the end a book is just a book.

Jackson, Mississippi August 2018

ABBREVIATIONS

Ancient works and authors have been abbreviated as in Brill’s New Pauly: Encyclopedia of the Ancient World. Modern journals of the classical world have been abbreviated as in L’année philologique. The following modern works have also been abbreviated:

DK H. Diels and W. Kranz. 1951–52. Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, 3 Vols.6 Berlin.

FD Fouilles de Delphes Paris.

FGrHist F. Jacoby et al. 1923–. Die Fragmente der griechischen Historiker. Leiden.

IG 1873–. Inscriptiones Graecae. Berlin.

LSJ H. G. Liddell, R. Scott, H. S. Jones, et al. 1996. A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford.

ML R. Meiggs and D. Lewis. 1969. A Selection of Greek Historical Inscriptions to the End of the Fifth Century B.C. Oxford.

PCG R. Kassel and C. Austin. 1983– Poetae Comici Graeci. Berlin.

PMG D. L. Page. 1962. Poetae Melici Graeci. Oxford.

RO P. J. Rhodes and R. Osborne. 2003. Greek Historical Inscriptions, 404–323 BC. Oxford.

West² M. L. West. 1998. Iambi et Elegi Graeci ante Alexandrum Cantati.² Oxford.

SEG Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum.

Syll.³ W. Dittenberger. 1960. Sylloge Inscriptionum Graecarum, 4 Vols.³ Hildesheim.

NOTE ON SOURCES

It has been my practice to use translations whenever possible and to modify or provide my own only when necessary. Translations are credited throughout with the last name of the translator, which corresponds to the list provided here. Modifications are noted where relevant. If unaccompanied by a name, the translation is my own.

Adams C. D. Adams. 1919. The Speeches of Aeschines. Cambridge, MA.

Bury R. G. Bury. 1929. Plato IX: Timaeus, Critias, Cleitophon, Menexenus, Epistles. Cambridge, MA.

Campbell

D. A. Campbell. 1991. Greek Lyric III: Stesichorus, Ibycus, Simonides, and Others. Cambridge, MA.

D. A. Campbell. 1993. Greek Lyric V: The New School of Poetry and Anonymous Songs and Hymns. Cambridge, MA.

Cooper I. Worthington, C. R. Cooper, and E. M. Harris. 2001. Dinarchus, Hyperides, and Lycurgus. Austin.

DeWitt and DeWitt N. W. DeWitt and N. J. DeWitt. 1949. Demosthenes VII: Funeral Speech, Erotic Essay (LX, LXI), Exordia and Letters. Cambridge, MA.

Emlyn-Jones and Preddy C. Emlyn-Jones and W. Preddy. 2013. Plato V: Republic I, Books 1–5. Cambridge, MA.

Geer R. M. Geer. 1947. Diodorus of Sicily IX: The Library of History, Books XVIII–XIX.65. Cambridge, MA.

Hammond M. Hammond. 2009. Thucydides: The Peloponnesian War, with an Introduction and Notes by P. J. Rhodes. Oxford. Harris I. Worthington, C. R. Cooper, and E. M. Harris. 2001. Dinarchus, Hyperides, and Lycurgus. Austin. Henderson J. Henderson. 1998–2002. Aristophanes, 4 Vols. Cambridge, MA.

Jones W. H. S. Jones. 1918–35. Pausanias, Description of Greece, 4 Vols. Cambridge, MA.

Lamb W. R. M. Lamb. 1930. Lysias. Cambridge, MA.

Maidment

Mensch

Natoli

Oldfather

Papillon

Paton

Pearson

Perrin

Purvis

Race

K. J. Maidment. 1941. Minor Attic Orators I: Antiphon, Andocides. Cambridge, MA.

P. Mensch. 2010. The Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of Alexander, Edited by J. Romm and R. B. Strassler with an Introduction by P. Cartledge. New York.

A. F. Natoli. 2004. The Letter of Speusippus to Philip II: Introduction, Text, Translation and Commentary. Stuttgart.

C. H. Oldfather. 1946. Diodorus of Sicily IV: The Library of History, Books IX–XII.40. Cambridge, MA.

T. L. Papillon. 2004. Isocrates II. Austin.

W. R. Paton. 1916. The Greek Anthology I, Books I–VI. Cambridge, MA.

W. R. Paton. 1925. Polybius IV: The Histories, Books IX–XV. Cambridge, MA.

L. Pearson and F. H. Sandbach. 1965. Plutarch: Moralia XI. Cambridge, MA.

B. Perrin. 1914. Plutarch, Lives II: Themistocles and Camillus, Aristides and Cato Major, Cimon and Lucullus. Cambridge, MA.

B. Perrin. 1916. Plutarch, Lives IV: Alcibiades and Coriolanus, Lysander and Sulla. Cambridge, MA.

B. Perrin. 1919. Plutarch, Lives, VII: Demosthenes and Cicero, Alexander and Caesar. Cambridge, MA.

B. Perrin. 1921. Plutarch Lives, X: Agis and Cleomenes, Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus, Philopoemen and Flamininus. Cambridge, MA.

A. L. Purvis. 2007. The Landmark Herodotus, The Histories, Edited by R. B. Strassler with an Introduction by R. Thomas. New York.

W. H. Race. 1997. Pindar, 2 Vols. Cambridge, MA. Rolfe

Sommerstein

Tredennick

J. C. Rolfe. 1946. Quintus Curtius: History of Alexander I, Books 1–5. Cambridge, MA.

A. H. Sommerstein. 2008. Aeschylus I: Persians, Seven against Thebes, Suppliants, Prometheus Bound. Cambridge, MA.

H. Tredennick and E. S. Forster. 1960. Aristotle II: Posterior Analytics, Topica. Cambridge, MA.

Usher

S. Usher. 1985. Dionysius of Halicarnassus: Critical Essays II. Cambridge, MA.

Vince J. H. Vince. 1930. Demosthenes I: Olynthiacs, Philippics, Minor Public Speeches, Speech against Leptines, I–XVII, XX. Cambridge, MA.

Waterfield

Welles

R. Waterfield. 1998. Plutarch: Greek Lives, with Introduction and Notes by P. A. Stadter. Oxford.

C. B. Welles. 1963. Diodorus of Sicily VIII: Library of History, Books XVI.66–XVII. Cambridge, MA.

West M. L. West. 1999. Greek Lyric Poetry. Oxford.

Yardley

J. C. Yardley. 2017. Livy: History of Rome IX, Books 31–34, Introduced by D. Hoyos. Cambridge, MA.

MAPS

Orchomeno

Platae a Paga e Auli s Tanagra

Ambraci a Lami a

Chaerone

Epidaurus Hermione Phlius

Isthmi a TirynsTroeze n Neme a Mycena e Megalopoli s Orchomeno s Lepreum Eli s

103:

104: Base of th e Corcyrean Bull

105: Base of th e Arcadians

106: Base of Philopoem en

108:

109: Aegospotami Monument

110: Marathon Statu e Group

112:

223-225: Athenian Treasury and Statue Group

MAP 2 Delphi

TEMPLE TERRAC E SACRED

303: Treasury of Brasidas and the Acanthians (?)

313: Athenian Portico

407: Base of th e Serpent Column

408: Base of the Crotonians

410b: Base of th e Salamis Apollo

417: Altar of Apollo

420: Eurymedon Monument

422: Temple of Apollo

518: Deinomenid Monuments

(Plate 5 in J.- F. Bommalear. 1991. Guide de Delphes: Le site. Paris)

Introduction

THE COLLECTIVE MEMORIES OF THE PERSIAN WAR

Introduction

In 340/39 BCE the orator Aeschines was dispatched to serve as the Athenian representative to the Delphic Amphictyony, an international body that oversaw the sanctuary at Delphi. Even for the fourth century the political situation was exceptionally volatile. Athens was at war with Philip II of Macedonia, but for now hostilities were limited to the north. A direct attack on Athens was unlikely. Philip had crossed into central Greece some six years earlier to support the Thebans in their fight against the Phocians, but now Philip had no such excuse, and his relations with the Thebans were not such that he felt confident to return uninvited. Yet Thebes was certainly no friend to Athens. In spite of their earlier cooperation against Sparta, relations between the two had cooled considerably since the battle of Leuctra had made Thebes the most powerful polis in Greece almost a generation earlier. The Athenians had quickly sided with Sparta and had more recently supported the Phocians in their unsuccessful war against Thebes. When Aeschines arrived at the meeting of the Amphictyony, the situation was explosive, and the match that set it off was a dispute over how the Persian War ought to be remembered.1

A little over thirty years before, the temple of Apollo at Delphi, long ago built by the Alcmeonid clan of Athens, had been destroyed in an earthquake. By 340/39 sufficient progress had been made on the new temple for the Athenians to decorate its architraves with golden shields. The shields were intended to commemorate Athenian participation in the Persian War. Aeschines provides

1 I use the singular, Persian War (as opposed to the more common “Persian Wars”), throughout as a general term to refer to the series of conflicts between the Greeks and Persians from the reign of Cyrus in the mid-sixth century to the end of the Delian League’s active operations against the Persians in the mid-fifth century. For a justification of this decision, see Chapter 4, pp. 137–38.

the dedicatory inscription, which read: “The Athenians, from the Persians and Thebans when they were fighting against the Greeks” (Ἀ

Given the strained relations between Athens and Thebes at the time, the shields proclaimed a particularly divisive recollection of the war.2 The Thebans were infuriated and had their allies, the Amphissians, propose a significant fine on the Athenians in the Amphictyonic Council both for dedicating the shields prior to the consecration of the temple and for inscribing them as they did. In response, Aeschines attacked the impiety of the Amphissians with such ferocity that the ire of the council was actually turned against the accusers. A sacred war was declared against the Amphissians, which gave Philip the excuse he needed to enter central Greece. Athens gathered what allies it could (Thebes included) and marched to defeat at Chaeronea in the next year.3

At the heart of the altercation over the golden shields stood two very different versions of the Persian-War past. The Thebans had submitted to Xerxes in the wake of Thermopylae, but later presented their collaboration with Persia (or Medism) as the result of compulsion. When the Persian War was mentioned at Thebes, emphasis seems to have been placed on the abortive expedition to Tempe in Thessaly and the defensive action at Thermopylae, where the Thebans claimed to have served the Greek cause with distinction. Their collaboration with Persia was generally and understandably ignored.4 The situation at Athens was quite different. The Athenians stood at the forefront of the fight against Xerxes and often claimed that the overall victory could be attributed to their efforts alone. Persian-War memorials dotted Athens and Attica. At Delphi the golden shields were just one of at least four magnificent Athenian monuments to the war with Persia. When the Thebans were mentioned, their Medism was condemned in no uncertain terms.5 It is notable, however, that the facts of the case were hardly in dispute. The Thebans never claimed that they did not ultimately Medize. What was at issue here was how those facts should be framed, interpreted, and presented—and where.

There was undoubtedly a panhellenic dimension to this incident. The temple of Apollo at Delphi was one of the most visited and visible structures in the Greek world. The shields’ unmistakable message of Athenian heroism and Theban betrayal was meant for panhellenic consumption. When the Thebans took offense, they responded through a panhellenic body, the Delphic Amphictyony. Although the delegates did not ultimately come to a decision about the shields,

2 For more on this dedication, see Chapter 5, p. 177, and Chapter 7, p. 256 n.29.

3 For more on the sequence of events that led to the Fourth Sacred War, see Ellis 1976: 186–90, Londey 1990, and Hammond 1994: 139–42.

4 See Chapter 6, pp. 229–31 for more on the Theban memory of the Persian War.

5 For more on the Athenian commemoration of the Persian War, see Chapter 5; for more on the Persian-War monuments erected at Delphi, see Chapter 3.

no one doubted the competence of this international body to judge the propriety of the dedication and its inscription. But despite the panhellenic setting, neither the Athenians nor the Thebans were advancing anything that could be called a commonly accepted Greek memory of the war. Theban attempts to mollify charges of Medism were variously accepted or rejected, depending on one’s attitude toward the Thebans at the time. Athenian heroics were a staple in the Athenian tradition, but seldom appear in the traditions of the other Greek poleis in the classical period. Yet, it is not simply the case that the Athenian shields were parochial in outlook. The inscription was designed to offend. The absence of any other Medizers and the fact that the Thebans and Persians were placed in explicit opposition to “the Greeks” leaves the distinct (and false) impression that the Thebans alone betrayed an otherwise united Greece. Far from representing a panhellenic version of the past, the Athenian shields emphasized and aggravated the deep fissures within the Greek world.

Above all, this episode underscores the stakes involved in the recollection and commemoration of the Persian War. Roughly a century and a half after Xerxes’s invasion, the political map of Greece had changed considerably. Beaten by the Thebans at Leuctra and broken by repeated invasions, Sparta was a shadow of its former self. The Peloponnese, once a bulwark of Spartan power, was now a hive of fractious poleis and shifting alliances. Athens had regained hegemony over much of the Aegean in the decades after the Peloponnesian War, only to lose it again during the Social War. It remained a force to be reckoned with, but it would never return to the heights of power reached after the Persian War. Thebes had bested Sparta at Leuctra, but a subsequent vacuum of leadership at home and a ruinous war with the Phocians had cost them dearly. A weakened Thebes continued to vie with Athens for primacy, even as new and more dangerous threats were emerging on the fringes of the Greek world. When Aeschines addressed the Amphictyony in 340/39, one such threat, Philip of Macedonia, was poised to enter central Greece on any pretext, and yet even then the memory of the Persian War was thought important enough to upset the delicate balance.

At first glance, the contentious fight over the golden shields at Delphi might appear to be an exception within the Persian-War tradition. The Thebans and Athenians fought against each other in the Persian War, after all, and despite a few decades of cooperation in the fourth century, their relationship had been largely hostile. Naturally they would have had different and indeed conflicting memories of the Persian War. But in the present study I intend to demonstrate that such differences were in fact typical of the Persian-War tradition in the classical period. I argue (1) that the Greeks recalled the Persian War as members of their respective poleis, not collectively as Greeks, (2) that the resulting differences were extensive and fiercely contested, and (3) that a mutually accepted recollection of the war did not emerge until Philip of Macedonia and Alexander the Great shattered the conceptual domination of the polis at

the battle of Chaeronea. These conclusions suggest that any cohesion in the classical tradition of the Persian War implied by our surviving historical accounts (most notably Herodotus) or postulated by moderns is illusory. Like Athens and Thebes, each city-state used the common facts of the war to create a largely idiosyncratic story about its past.6

The idea that the individual poleis of the classical period had different conceptions of the Persian War and that those conceptions were often in competition with each other is neither new nor particularly controversial.7 Yet the extent of these differences and the intensity with which the Greeks competed over them has never been adequately explored. This is in no small part because Persian-War memory has by and large been studied only in segments. Most modern treatments focus on a single battle or source.8 As a result, although individual aspects of Persian-War memory have received attention, the whole remains largely understudied. Even Jung’s learned examination of Marathon and Plataea as lieux de mémoire has similar limitations.9 These two battles were frequently commemorated and did (among most Athenians at least) bookend the war,10 but a representative picture of the full tradition eludes us without a consideration of Thermopylae, Artemisium, Salamis, and Mycale—to say

6 Polis is a much debated term, which in antiquity could refer to an urban settlement, that settlement along with its surrounding territory, a political community, or often all three together. For more on the nature and definition of the polis, see M. Hansen 1997, 2000, 2004, and 2006, J. Hall 2007 and 2013, van der Vliet 2007, Gehrke 2009, and Strauss 2013. It is, however, only the third definition that concerns us here (see also note 52). Consequently, I use the words polis, city-state, state, and polity throughout with no meaningful distinction intended, to refer to any type of nominally autonomous political community.

7 The point was made long ago by Starr 1962: 328–30, citing Herodotus, and has become axiomatic in the study of Persian-War memory; see W. West 1970, Hölscher 1998b: 84–103, Jung 2006: 225–97, Marincola 2007, Vannicelli 2007, Beck 2010, Higbie 2010, Cartledge 2013: 122–57, Yates 2013, and Morgan 2015: 150–54.

8 Marathon has been the subject of numerous studies. Three recent edited volumes focus in part on the memory of that battle (Buraselis and Meidani 2010, Buraselis and Koulakiotis 2013, and Carey and Edwards 2013). They join earlier articles by Flashar 1996, Hölkeskamp 2001, Gehrke 2003 (= 2007), and Zahrnt 2010 on the same subject. The commemoration of Thermopylae has been examined by Flower 1998, Cherf 2001, Albertz 2006, Vannicelli 2007, M. Meier 2010, and Matthew and Trundle 2013; Salamis by Ruffing 2006; and Plataea by Beck 2010: 61–68. Jung’s 2006 treatment of Marathon and Plataea is considered in some detail later. Individual sources or groups of sources have also received attention. A few examples will suffice to illustrate the trend. Gauer 1968 assembles all the surviving and attested dedications. W. West 1970 and Higbie 2010 consider the surviving Persian-War epigrams. Spawforth 1994, Alcock 2002: 74–86, and Russo 2013 review Roman uses of the Persian War. Boedeker 1995, 2001a, and 2001b devote significant attention to Simonides. T. Harrison 2000 examines Aeschylus’s Persae. Marincola considers fourth-century historiography and oratory (2007) as well as Plutarch (2010). Rowe 2007 focuses on Plato. Cartledge 2013 provides a thorough treatment of the so-called Oath of Plataea. Yates 2013 reviews the evidence for the temple of Athena Areia at Plataea. Studies that treat some aspect of Herodotus’s presentation of the Persian War are too numerous to mention here, but see Chapter 2, pp. 80–87 for a selection.

9 Jung 2006.

10 This is the assertion of Plato’s Athenian interlocutor in the Laws 707c (with Jung 2006: 13), but see Chapter 4 for more on the various periodizations of the war.

nothing of more “peripheral” battles like Lade, Himera, Eurymedon, or Cyprian Salamis.11 Moreover, the monuments and narratives surrounding any one battle, even a battle as apparently separable as Marathon, can only be completely understood in relation to the others. Indeed, some of the most magnificent Marathon monuments were erected almost a generation after the fact and so in full awareness of the subsequent commemoration of Xerxes’s failed invasion.

In the absence of a detailed study of the entire Persian-War tradition, Herodotus’s Histories and the extensive evidence from Athens have cast a long shadow. This is not at all surprising. Herodotus is one of our earliest and certainly our fullest source for the Persian War. The wealthy polis of Athens supplies the largest number of surviving Persian-War commemorations, which have consequently received greater scholarly attention.12 The effects are widespread. Trends apparent only in Athens are often thought to have had purchase throughout the Greek world, or conversely, broad trends are supposed to have had a distinctly Athenian character.13 Such conclusions can impart a false sense of unity to the overall tradition and overstate the extent to which Athens influenced it. Herodotus gives us ample reason to doubt both propositions. In Book 7 he famously anticipates a broadly negative reaction to his conclusion that the Athenians had proven to be the saviors of Greece (7.139), a common Athenian claim in the fifth and fourth centuries. Despite an alleged Athenian bias, Herodotus was capable of seeing the Persian War from multiple perspectives and often cites significant regional differences without hesitation.14 At first glance, then, the Histories would seem to provide a satisfying scaffold on which to assemble our surviving evidence.15 But for all the times that Herodotus underscores variations within the Persian-War tradition, he nevertheless organizes them within a single overarching narrative.16 We mistake literature for reality if we assume that this narrative unity had any existence outside of Herodotus’s Histories

11 It should be noted that Jung 2006: 22–24 fully acknowledges these limitations.

12 See Flashar 1996, Hölkeskamp 2001, Gehrke 2003 (= 2007), Jung 2006, Ruffing 2006, Buraselis and Meidani 2010, Buraselis and Koulakiotis 2013, and Carey and Edwards 2013. To this list can be added earlier studies by Loraux 1986, Castriota 1992, Green 1996b, and T. Harrison 2002a, each of which devotes significant attention to the presentation of Athenian identity as well as the uses to which the Persian War was put in support of it.

13 See, for example, E. Hall 1989: 2, R. Thomas 1989: 223, Castriota 1992: 65 and 90, T. Harrison 2002a: 4, and J. Hall 2002: 182–89 and 205.

14 See, for example, Vannicelli 2007.

15 The tendency of scholars to rely on Herodotus’s Persian-War account has been noted by Marincola 2007: 105–106 generally and by Schreiner 2008: 412 specifically in reference to Jung 2006. For examples of this trend in history and memory, see Starr 1962: 322, T. Harrison 2000: 62, and Vannicelli 2007: 316.

16 For more on the relationship between history and memory, see pp. 26–27.