Introduction

What was alchemy? Or what is alchemy? Whatever it might be, it is clearly not a thing of the past alone or the exclusive preserve of historians. Instead, alchemy is something that continues to fascinate not only self-professed contemporary alchemists but also scientists, artists, psychologists, and a variety of spiritual seekers. It also appeals to readers of popular fiction such as Paulo Coelho’s 1988 novel The Alchemist or J. K. Rowling’s series that began with Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone in 1997.1 Some might say, and with good reason, that these are questions that cannot be answered, presuming as they do that it would be possible to provide a single definition that captures the meaning of ‘alchemy’ over the course of almost two millennia. Yet throughout the past three centuries there have been three dominant attempts at answering these questions. In a nutshell, alchemy has been viewed as superstition and fraud, as religion and psychology, as science and natural philosophy. These answers closely reflect an underlying triad of highly problematic reifications that have underpinned grand narratives of humanity’s history since the nineteenth century: magic, religion, and science.2 Despite the many problems of these categories to which scholars have been drawing attention for years, they continue to powerfully inform the way we think about history, its long-term trajectories, and our place within them as modern, rational, and secular individuals in an age dominated by science.

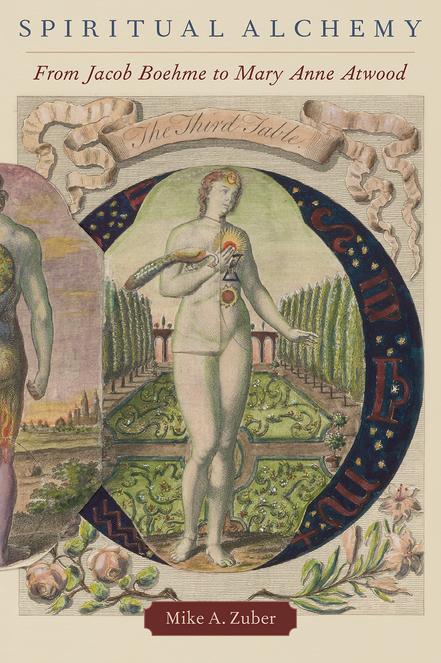

The very fact that such divergent answers to what alchemy was and is could be taken to suggest that its complex history and that history’s reception defy these fundamental categories. By resisting a straightforward definition, alchemy unsettles the all-too-neat triad of science, religion, and magic. Indeed, the very term that appears in the title of this book, ‘spiritual alchemy,’ seems to undermine any attempt at classification: it hints at something that is neither fish nor fowl, neither science nor religion as they are commonly understood. In this introduction, I first explore three widespread views of alchemy and outline a new stance regarding the two more important ones, a strictly historicist perspective that affords us the privilege of not having to commit to either. Second, I define the subject of this book and clarify why ‘spiritual

Spiritual Alchemy. Mike A. Zuber, Oxford University Press. © Oxford University Press 2021. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190073046.003.0001

alchemy’ is the most appropriate term for it. The introduction concludes with a brief outline of the book’s chapters.

Competing Views of Alchemy

The three main views of alchemy just described continue to be defining for both public perceptions of and scholarly debates on the art of the adepts. Starting in the 1720s, Enlightenment polemicists such as Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle, spokesman of the Parisian Académie des sciences, denounced the art of the philosophers’ stone—the fabled transmuting agent that would turn base metals into gold. He painted alchemy as utterly misguided and fraudulent, associated it with superstition and dishonesty, and contrasted it with chemistry.3 Later proponents of this view classed alchemy as a ‘pseudoscience,’ and until 2002 that was the category where the annual bibliography of Isis, the leading journal for the history of science, placed research on the subject.4 This view would lead us to neglect alchemy as the worthless intellectual ‘rubbish’ produced by a superstitious past.5 In fact, engaging with it might even harm our sanity: in an oft-quoted statement, Cambridge historian Herbert Butterfield famously pronounced that historians of alchemy seem to incur ‘the wrath of God’ and ‘to become tinctured with the kind of lunacy they set out to describe.’6 While this attitude still occasionally surfaces, historians no longer take it seriously.

From the middle of the nineteenth century, a considerably more flattering understanding of alchemy developed, one that viewed adepts as engaging not primarily with material substances. Instead, the alchemists of old were allegedly concerned with the transmutation of their inner selves, a process that might be construed in a religious, spiritual, psychological, or moral manner. In 1850 Mary Anne South, who became better known as Mrs Atwood, anonymously published a sprawling work titled A Suggestive Inquiry into the Hermetic Mystery. Engaging with the unconventional interests of her father, Thomas South, she presented alchemy as similar but superior to Mesmerism as a means for attaining the ancient aims of mysticism. Independently and almost simultaneously, the American major general Ethan Allen Hitchcock presented a moral interpretation. As he explained in 1855 and 1857, the philosophers’ stone stood for ‘truth, goodness, moral perfection, the Divine blessing’: these were the goals that medieval alchemists, who were really ‘Reformers’ and ‘Protestants’ avant la lettre, pursued and discussed

throughout their treatises.7 Hitchcock’s work became an important point of reference for the Viennese psychoanalyst Herbert Silberer, a longtime member of Sigmund Freud’s circle. He influentially linked alchemy to both mysticism and psychology in his 1914 book Probleme der Mystik und ihrer Symbolik (Problems of Mysticism and Its Symbolism).8

In the twentieth century, this second understanding shaped scholarship on alchemy to a significant extent, in part because the first view discouraged active engagement with the mysterious art. Romanian-born historian of religion Mircea Eliade viewed alchemy as a ‘spiritual’ quest ‘pursuing a goal similar or comparable to that of the major esoteric and “mystical” traditions.’ He clearly stated that ‘alchemists were not interested—or only subsidiarily—in the scientific study of nature.’9 The Swiss psychiatrist C. G. Jung is probably the most prominent exponent of a psychological conception of the royal art, and his work on alchemy informed scholarship for a considerable part of the twentieth century. In fact, it provided the dominant paradigm for research on the subject from the 1940s to the 1990s.10 In contrast to Eliade, Jung viewed the experimental study of nature as defining: he described an ideal or classical alchemy, ‘in which the spirit of the alchemist really still wrestled with the problems of matter, in which the inquisitive consciousness faced the dark space of the unknown and believed that they recognised shapes and laws therein, though these did not originate in the matter but in the soul.’ In contrast to simplified accounts, Jung clearly held that actual laboratory work provided the basis for this to occur and lamented its neglect in the wake of Jacob Boehme, who died in 1624.11 It is thus no coincidence that Boehme, the theosopher of Görlitz, plays a pivotal role in the story told in these pages.

Even as he acknowledged the experimental side of alchemy and considered it foundational, Jung—the inventor of analytical psychology—was chiefly interested in alchemical imagery. He interpreted it as the projections of the unconscious. His 1946 contribution to Ambix, the leading journal for the history of alchemy and chemistry, described the art of the philosophers’ stone as ‘a real museum of projections.’ Jung provocatively claimed that ‘its history should never have been treated by chemists, for it offers an ideal hunting-ground for the psychologists.’12 According to him, the approach to alchemy taken by chemists obscured much of its richness, which he as a psychologist was better able to appreciate and communicate. Jung’s interpretation of alchemy was an attempt to understand its nigh-impenetrable language and fascinating symbolism that was fresh and stimulating at its time. It played the important role of establishing that alchemy was worthy of serious

inquiry rather than dismissal. Even pioneering historians such as Betty Jo Teeter Dobbs, who worked extensively on Isaac Newton’s alchemy, initially approached the art through Jungian lenses.13 To this day, Jung’s views inform popular portrayals and perceptions of alchemy and still continue to stimulate interest in the subject.

While mild criticism of Jung’s ahistorical approach accompanied his reception in the historiography of alchemy from the start, only in 1982 did Swiss art historian Barbara Obrist call for its abolition and present a convincing critique.14 According to her trenchant analysis, the very popularity of Jung’s work had led to ‘general confusion’ due to an inflationary use of the term ‘alchemy’ that saw it applied to all sorts of evocative art, including mythological depictions and the work of the famous Dutch artist Hieronymus Bosch.15 If all intriguing imagery could be studied as alchemy, the term risked losing any analytical value it possessed. Two historians of science, William R. Newman and Lawrence M. Principe, have since expanded on Obrist’s criticism of Jung. Through a series of studies, they successfully replaced Jung’s approach with a new paradigm, known as the New Historiography of Alchemy, and firmly integrated alchemy into the history of science.16 In particular, Newman and Principe reproduce alchemical processes experimentally by decoding arcane language and imagery, thus demonstrating an alternative, historical interpretation for what Jung viewed as timeless ‘psychic processes expressed in pseudochemical language.’17 Among specialists working in an Anglophone context, the ‘old historiography’ is now definitely a thing of the past. Scholarly debates in other linguistic contexts have been struggling to keep up with the rapid developments brought about through the New Historiography.18

In a classic article, ‘Alchemy vs. Chemistry: The Etymological Origins of a Historiographic Mistake,’ published in 1998, Newman and Principe challenge a widespread dichotomy as based on faulty etymology. Chemistry traditionally represents ‘the modern, scientific, and rational,’ while alchemy is alternately viewed negatively as ‘the archaic, irrational, and even consciously fraudulent’ or idealised and romanticised as having a defining ‘spiritual or psychic dimension. ’19 Newman and Principe argue that both terms were employed synonymously prior to the late seventeenth century. Early-modern authors routinely used the term ‘alchemy’ to refer to what we would recognise as chemistry and ‘chemistry’ for what we deem quintessentially alchemical, for example the transmutation of metals. Establishing this discrepancy is a key insight that cannot be passed over and that highlights the complexities

of the historical record. To name but one famous example, Andreas Libavius’ voluminous Alchemia of 1597 ‘is usually and fairly described as the first textbook of chemistry’ or ‘a landmark in chemical literature. ’20 To avoid the problem of a false dichotomy, Newman and Principe recommend that scholars use the archaic ‘chymistry’ as well as other, more specialised terms encountered in historical sources.21

Principe and Newman further explore this issue in a crucial study titled ‘Some Problems with the Historiography of Alchemy.’ This landmark publication criticises ‘a “spiritual” interpretation of alchemy,’ which views ‘alchemical adepts as possessors of vast esoteric knowledge and spiritual enlightenment.’ Principe and Newman locate the historical origins of this view in ‘nineteenth-century occultism,’ among writers such as Atwood and Hitchcock. Projected back onto earlier alchemy, their interpretations amount to anachronistic misrepresentations: Principe and Newman ‘find no indication that the vast majority of alchemists were working on anything other than material substances toward material goals.’22 Instead of portraying alchemists as otherworldly initiates, the New Historiography thus places them in the company of miners, metallurgists, assayers, distillers, pharmacists, and even balneologists, all of whom drew on chymical techniques to work with material substances toward many different practical, entrepreneurial, and medical ends. Taken together, the importance of these two essays cannot be overstated, as Principe and Newman made a cogent case for a fresh start that has come to define the field for the past two decades. Whereas it seemed clear to earlier generations of researchers that alchemy was either an outright pseudoscience or primarily spiritual, religious, moral, or psychological, the New Historiography has led historians to see alchemy as predominantly scientific and experimental or, to use a more historic term, related to natural philosophy.

Nevertheless, there are also scholars who criticise the New Historiography from various perspectives.23 Though they all have different aims and angles, all of these critics agree that the New Historiography implies an overly restrictive view of its subject and downplays important aspects in favour of chemical content and experimental technique. This tendency can lead to an implicit portrayal of alchemy as a kind of proto-chemistry obscured by strange imagery and secrecy. Due to the very success of the New Historiography and its approach, there is the danger of a latent essentialism that could lead, and in some cases alre ady has led, to an implicit view of alchemy as ‘ “really” science (and not religion).’ This is simply the antithesis of earlier views holding that

‘alchemy may sometimes look like science, but it is really psychology or religion,’ as Wouter J. Hanegraaff summarises them.24

My aim in this book is not to continue a long-standing tug of war regarding the essence of alchemy, which in effect, as Hanegraaff points out, goes back to the ‘conflict thesis’ of science and religion, formulated in the nineteenth century.25 In view of the changing faces of the philosophical art through history, it seems unlikely that either the ‘alchemy is scientific’ or the ‘alchemy is religious’ team will ever succeed in pulling its opponents across the line. To transcend this futile contest, we need to adopt the perspective of an impartial observer and identify alchemy itself as part of the game: it is the rope. Even as the teams pull it toward the ‘science’ or ‘religion’ side, they both hold on to integral, if different, parts of the same rope, which reaches across the entire playing field. By its refusal to neatly fit either label, alchemy can actually call into question science and religion as categories of analysis too often taken for granted. This tendency is heightened further by narrowing down the subject to ‘spiritual alchemy,’ a contested term sometimes used to highlight the religious elements encountered within alchemical literature.

Spiritual Alchemy

Based on the advances of the New Historiography, the aim of this book is to study the religious aspects of alchemy seriously and rigorously.26 This entails a different approach than viewing alchemy as primarily religious, spiritual, moral, or psychological: one would simply take religious elements for granted. Yet it is a rather curious fact that, from the very oldest surviving sources, we do encounter religious dimensions in alchemical sources. The alchemist Zosimos of Panopolis in Hellenised Egypt, for instance, was familiar with gnostic teachings that emphasised humans’ need for salvific knowledge to escape the prison of the mortal body and return to the divine. He interspersed his alchemical treatises with various dreams or visions. Based on the apocryphal Book of Enoch, Zosimos even held that fallen angels had taught humankind the art of alchemy.27 From the beginning, according to Pamela H. Smith, the literature of alchemy ‘included a remarkable accretion of religious and gnostic concerns with the relationship of matter and spirit.’28 Even in much later sources, this situation persists. In the fourteenth century, the Italian author Petrus Bonus wrote a treatise on alchemy titled Pretiosa margarita novella (Precious New

Pearl), which contains a chapter arguing ‘that this art is both natural and divine.’29 The earliest known German work of alchemy, the Liber Trinitatis (The Book of the Trinity), composed in the 1410s, details extended analogies between Jesus Christ and the philosophers’ stone.30 Though the text of the work remains largely inaccessible, its cycle of images became part and parcel of later alchemical literature. The Rosarium philosophorum (Rosary of the Philosophers), first published in 1550, was an early and widely disseminated example of this reception. The alchemical process described in the Rosarium culminates with the philosophers’ stone that is visually portrayed as the risen Christ.31

Scholars have used a variety of terms, including ‘spiritual alchemy,’ to draw attention to these conspicuous elements of alchemical literature. Unfortunately, the usefulness of these terms is at times exhausted in doing just that. The late literary scholar Joachim Telle, during his lifetime the outstanding expert on the manuscript record of German alchemy, frequently employed the deliberately vague term ‘theoalchemy’ (Theoalchemie) to describe the mingling of alchemy with theology that could take place in any number of ways.32 Apart from its evocative, signalling power, this coinage is of very limited analytical value. More problematic still are terms that suggest easy binaries, such as ‘exoteric alchemy’ and ‘esoteric alchemy’ or ‘material alchemy’ and ‘spiritual alchemy.’33 Principe rightly notes that such distinctions go all the way back to the nineteenth century and basically amount to the old dichotomy of chemistry and alchemy.34

The term I have chosen for the phenomenon scrutinised throughout this book is not unproblematic. It has frequently been used to advance claims regarding the allegedly religious essence of alchemy. Moreover, a certain confusion surrounds ‘spiritual alchemy’: it is used to refer both to scholarly (and not-so-scholarly) approaches to alchemy and to actual content in historical sources.35 The problem here is not that either of these meanings—interpretive approach versus historic ideas or practices—attached to the term ‘spiritual alchemy’ are wrong: actually, the interpretive approach to alchemy as something religious or spiritual has a very rich history of its own. It is, however, imperative to keep these two significations of spiritual alchemy apart. Only if we reserve the term ‘spiritual alchemy’ for precisely circumscribed historical and textual phenomena can it serve as a useful category of analysis. Despite the problems of ‘spiritual alchemy’ and the various alternatives scholars have proposed, I argue that there is no term better suited to the phenomenon investigated in this book.

Unlike some of its alternatives, spiritual alchemy has a number of historic approximations. Here are examples that appear in sources dating from around 1600 to the mid-eighteenth century: ‘divine alchemy’ (gottliche Alchimiam), ‘spiritual alchemy’ (alchymia spiritualis), ‘spiritual chrysopoeia’ (geistliche Goldmachung), and ‘mystical alchemy’ (Alchymia Mystica); even English ‘Spiritual Chymistry’ and German ‘spiritual chymia’ (geistliche Chymie) or ‘true spiritual chymia’ appear.36 While the occurrence of ‘mystical’ and ‘divine’ signals an intriguing overlap with the religious domain, ‘spiritual alchemy’ as studied in this book has little to do with contemporary notions of spirituality. Boaz Huss notes that spirituality is now frequently defined ‘in opposition to religion,’ which contrasts with ‘the early modern and modern perceptions of spirituality as a subcategory, or the essence of religion.’37

While some of the protagonists we shall encounter indeed viewed spiritual alchemy as defining for true Christianity, that is not the main point. Instead, the term ‘spiritual alchemy’ highlights early-modern understandings of spiritus. This term carried a bewildering array of meanings in vastly different contexts, particularly medicine and theology, but also anthropology, cosmology, and, last but not least, alchemy.38 Intellectual historian D. P. Walker has perceptively noted that, against this background, the word spiritus could give rise to ‘dangerous contaminations or confusions’ that might ‘lead towards religious unorthodoxies.’39 Spiritus vacillated between the divine and the physical, between medical and theological anthropology, between the matter of heaven and the products of the alchemist’s distillery. The interplay, interference, or even conflation of these various notions of spirit is crucial but often remains implicit.

To gain an understanding of what this looked like in practice, we might begin with the general medical understanding of spiritus. It was, writes Katharine Park, ‘a subtle vapour or exhalation produced from blood and disseminated throughout the body,’ serving as the soul’s instrument to control ‘all activity in the living body.’40 In a clear hierarchy, spirit thus mediated between the more noble soul and the inferior body. Credited with the recovery of Platonic philosophy for the early-modern world, the Florentine physician, philosopher, and translator Marsilio Ficino extended this scheme to the macrocosm and posited the spirit of the world (spiritus mundi) as a subtle matter that mediated between the soul of the world (anima mundi) and its body, the material world.41 Moreover, he identified the spiritus mundi as the quintessence and transmuting agent of alchemy. In so doing, Ficino inspired

many alchemists to pursue the spiritus mundi for centuries to come.42 Partly due to the Florentine philosopher, partly independently of him, the situation gets exceptionally tangled in alchemy. In a widely used collection of alchemical texts, for instance, the roles of spirit and soul are swapped, and we read that ‘spirit and body are one, through mediation of the soul.’43 Medical historian Marielene Putscher notes that this is not an isolated occurrence and that it is frequently difficult to assess ‘whether soul or spirit is the medium that establishes the connection to the body.’44

Furthermore, in a theory popularised by medical iconoclast Theophrastus Paracelsus Bombastus von Hohenheim and his followers, the three principles mercury, sulphur, and salt corresponded to spirit, soul, and body.45 In this manner, alchemical Paracelsianism contributed to the spread of a trichotomous anthropology among religious dissenters in the late sixteenth and throughout the seventeenth century, particularly in German-speaking Lutheran contexts: it was in this intellectual, religious, and cultural environment that spiritual alchemy developed. On the trichotomous view, spirit could refer to the divine spark, either preexistent within a human being and awaiting activation or implanted through rebirth.46 Rather than mediating between soul and body, the spirit could thus become the noblest component of the human being. This represented a notable departure from the dichotomous anthropology espoused by Aristotelian philosophy and orthodox Lutheran theology. From the perspective of the latter, the crux was that this third part of humans was not only immortal but divine: it was, quite literally, a part of God and would return to God after death.47 This view had far-reaching heterodox implications: sometimes the third component was effectively tied to an internalised Christus in nobis or participation in Christ’s heavenly, ubiquitous body, doing away with the need for the outward rituals of baptism and the Eucharist.48 Indeed, in the late seventeenth century, Lutheran heresy hunter Ehregott Daniel Colberg described ‘the delusion of the three substantial parts of man’ as the foundational error of ‘PlatonicHermetic Christianity’ from which all other heresies flowed.49

Bearing in mind the layers of meaning accruing around ‘spirit’ in the earlymodern world, I define the spiritual alchemy investigated here as the practical pursuit of inward but real bodily transmutation. This transmutation amounted to the reversal of the Fall and its consequences; furthermore, it prepared the faithful for the resurrection of the dead at the Last Judgement. This spiritual alchemy is thus closely connected to the idea of spiritual rebirth, which it helped shape and by which it was shaped in turn.50 Apart from the fact that,

from Jacob Boehme onward, all the figures studied here drew on his theosophy, there are three key elements of this alchemy. First, there is a three-way lapis-Christus in nobis analogy between the philosophers’ stone, Christ incarnate, and the believer who mystically identifies with Christ. This element harks back to the more traditional lapis-Christus analogy but significantly expands it by including the individual disciple. The mystical identification of Christ and the believer could be summed up in a single phrase: Christus in nobis, the notion that Christ dwells within his faithful who mystically relive his life on a daily basis. In the seventeenth century, this phrase became popular in heterodox circles on the fringes of Lutheranism. Through the immediate access to the divine guaranteed by the divine logos within the individual believer, the implications of Christus in nobis effectively made the clergy, the church, and at times even the Bible unnecessary.51

Second, there is a physical process toward restoring the prelapsarian body, characterised as subtle or spiritual, in preparation for life in Heaven. With regard to the resurrection of the dead, the second element is fairly amenable to Lutheran orthodoxy. The reformer Martin Luther himself had praised alchemy as a visible demonstration of this article of faith, and a court alchemist’s obituary explicitly called it ‘spiritual alchemy’ (geistliche Alchymia) around 1660.52 Yet there are two important differences that concern timing and agency. In contrast to the delayed bodily transmutation at the end of time, Boehme and his followers held that it began in the here and now, albeit imperceptibly and in ways that cannot be measured with the tools of science. Furthermore, the orthodox understanding reserves agency solely for God, in keeping with Luther’s principle of sola gratia (by grace alone): on this view, believers are passive matter in God’s hands rather than spiritual adepts who participate actively in the cultivation of their resurrection bodies.

The issue of agency leads on directly to the third aspect, which is the practical pursuit of that process of spiritual rebirth and its bodiliness through devotional acts or mystical paths. By practising spiritual alchemy, the individual believer actively nourishes the new birth within by means of prayer, penitence, ascetic deeds, or other rituals, which may also be purely internal or contemplative.53 By pursuing these practices over a prolonged period of time, spiritual alchemists attain higher stages in their quest for ever closer union with the divine. Sometimes the language of mysticism, particularly that of the three stages of purificatio, illuminatio, and unio, appears in these contexts. These devotional acts or mystical paths are explicitly described in terms of manual operations, alchemical techniques, or stages of the great

work. In a way, then, spiritual alchemy is a peculiar form of Protestant mysticism. Contrary to a widespread perception, there is nothing that should cause us to view this term as self-contradictory; in fact, mysticism had a rich and largely positive reception within early Protestantism.54 Yet the core three elements of spiritual alchemy do subtly depart from Lutheran orthodoxy by internalising Christ, emphasising rebirth, and requiring individual agency, respectively.

I cannot possibly stress enough that, in the interaction of these aspects, spiritual alchemy ceases to be merely metaphorical. If I had to reduce this entire book to a single point it would be this: Boehme and his later disciples believed that actual bodily changes—albeit not subject to the ordinary laws of physics or conventionally measurable—were taking place within them as they pursued the spiritual alchemy of rebirth and its processes.55 This is the defining feature of spiritual alchemy proper, as opposed to any number of religious tropes, conceits, or metaphors one might uncover in alchemical literature. It is the reason that this book focuses on Boehme and ends with Atwood rather than Hitchcock, whose moral interpretation of alchemy remained entirely allegorical. While we would tend to understand rebirth, deification, or mystical union as non-physical processes of religious transformation, that is not how Boehme and his followers viewed them. In other words, even though spiritual alchemy did originate as a metaphor or conceit, it did not remain so. Instead, spiritual alchemy came to be viewed as literally describing the physical transfiguration of the human body through rebirth in this life, culminating in resurrection at the Last Judgement. Even as it is challenging to transcend the hard-and-fast distinctions between mind and matter, soul and body, that is precisely what we need to wrap our minds around. Otherwise, it remains impossible to understand spiritual alchemy, predicated on the early-modern notion of spiritus. In important ways, therefore, the spiritual alchemy of rebirth is the alchemy of spiritus as the subtle matter of the new birth, the kingdom of heaven, and Christ’s human body turned heavenly. Through the spiritual alchemy of rebirth, believers could literally become members of Christ’s body, as the Pauline metaphor put it.56 Irrespective of what we might think of this nowadays, the most methodologically sound way of approaching spiritual alchemy is the suspension of disbelief. For the historical actors studied in this book, it was real. Consequently, we have to also view it as real in precisely the same sense as the sun used to revolve around the earth, astrological influence determined the fate of people and nations, and (perhaps most appropriately)