https://ebookmass.com/product/spinoza-and-the-freedom-of-

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Philosophizing the Indefensible: Strategic Political Theory Shmuel Nili

https://ebookmass.com/product/philosophizing-the-indefensiblestrategic-political-theory-shmuel-nili/

ebookmass.com

Reconceiving Spinoza Samuel Newlands

https://ebookmass.com/product/reconceiving-spinoza-samuel-newlands/

ebookmass.com

An Examination of the Singular in Maimonides and Spinoza: Prophecy, Intellect, and Politics 1st ed. Edition Norman L. Whitman

https://ebookmass.com/product/an-examination-of-the-singular-inmaimonides-and-spinoza-prophecy-intellect-and-politics-1st-ed-editionnorman-l-whitman/

ebookmass.com

How Not to Date an Angel (Cautionary Tails Book 4) Lana Kole

https://ebookmass.com/product/how-not-to-date-an-angel-cautionarytails-book-4-lana-kole/

ebookmass.com

Law Express: International Law 2nd Revised edition Edition

Stephen Allen

https://ebookmass.com/product/law-express-international-law-2ndrevised-edition-edition-stephen-allen/

ebookmass.com

Time, Temporality, and History in Process Organization Studies Juliane Reinecke

https://ebookmass.com/product/time-temporality-and-history-in-processorganization-studies-juliane-reinecke/

ebookmass.com

Never Stop Asking: Teaching Students to be Better Critical Thinkers Nathan D. Lang-Raad

https://ebookmass.com/product/never-stop-asking-teaching-students-tobe-better-critical-thinkers-nathan-d-lang-raad/

ebookmass.com

Transient Analysis of Power Systems: A Practical Approach

Editor: Juan A. Martinez-Velasco

https://ebookmass.com/product/transient-analysis-of-power-systems-apractical-approach-editor-juan-a-martinez-velasco/

ebookmass.com

Surface Process, Transportation, and Storage Qiwei Wang

https://ebookmass.com/product/surface-process-transportation-andstorage-qiwei-wang/

ebookmass.com

Code: The Hidden Language of Computer Hardware and Software 2nd Edition Charles Petzold

https://ebookmass.com/product/code-the-hidden-language-of-computerhardware-and-software-2nd-edition-charles-petzold/

ebookmass.com

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford Un iversity P ress is a department of th e University of Oxford. It furthers the Un iversity's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, an d educati on by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certai n other countries

© Mogens L.erke 202 1

The mora l rights of t he aut hor have been asserted First Edition published in 202 1

Impression: l

All r ights rese r ved No part of t his publication may be reproduced , stored in a retrieval system, or tra nsmitted , in any fo r m or by any m eans, without the prior pe r missio n in writing of Oxford University Press, o r as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the a p prop ri ate reprographics rights organizatio n Enquiries co ncerning reproduction o u tside the scope of the above should be sent to t he Rights Department, Oxfo rd University Press, at the ad dress above

You must not circulate this work in any other form a nd you must im pose this same cond ition on a n y acq u irer

Published in th e Uni ted States of America by Oxford Un ive rsity Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available

Library o f Congress Control Num ber: 2020947759

ISBN 978- 0 - 19 - 289541 - 7

DOI: 10.1093/oso/ 9780192895417.001.000 l

Printed and bound by CP I Group (U K) Ltd, Croydon, CRO 4YY

Links to third party websites ar e provided by Oxford in good fait h a nd for information only. Oxford d isclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in thi s wo rk

National Religion

The Hebrew Republic

12. Conclusion: The Dutch Public Sphere

A Note on Texts, Translations, and Abbreviations

As it remains customary in the English - lan guage literature, I reference th e orig ina l Latin or Dut c h texts in the four-volume editi on by Carl Geb ha rdt of 1925. Ge bhardt's edition is not without its flaws- indeed, far from it- but it is (or was, a t th e t ime of writin g this book) still th e m ost c urre ntly used one, and many oth er editions and re cent translations are keyed to its pagination. Whe n available, I have, howeve r, co n sta ntl y consulted th e new bilingual Latin - French ed itions from the Presses unive rsitaires de France for ve rifi cation purposes ( th e edition of th e TTP by Fokke Akkerman, Jacqueline Lagree, a nd Pierre-Franc;:ois Moreau; of the TP by Omero Proietti and C harles Ramond; of the TdI E by Filippo Mignini; o f th e KV b y Michelle Beyssad e a n d Joel Gana ul t; of the Ethics by Fokke Akkerman, Piet Steenb akkers, and Pierre-Fran c;:o is Moreau). As for the English re nderin g of Spin oza's text s, I follow Edwin C url ey's generall y outstandin g translations, although I do frequently d iverge from th em. When I do, it w ill be indicated in th e notes, o ften accompanied by an explanation, except when it comes to so me ge n e ral points that I discuss below. For a ll oth e r texts, both so u rces and com m e n tar ies, and whe n n o thin g else is indicated , trans lat ions are mine.

Curley reproduces the genero u s capitalizat ion of words used in Gebhardt's edition w hi ch re fl ects th at of th e first printed editions of Spinoza's works. Ho wever, available a utograp h s o f o th e r texts by Spin oza, or m a nuscri pt cop ies made by people close to him , 1 u se very little capitaliza ti o n a nd , as C url ey himself stresses, the re is no good reaso n to think th at th e capitalization s in prin t reflect an yt hin g but the typographical practices at th e original print ing house ofJan Ri euwe rtsz.2 I h ave therefore not fo llowed C urley on this point but capit alized acco rdin g t o contempo rary norms. C url ey also- no w moving to th e other edito ri a l extremeadds features to th e formatting of the poli tica l texts that are ab sent from th e first printings, s uch as indentations, va ri ations in fo nt size, et al. I have not foll owe d him on this point either. I find the a dditional fo rma tt ing-espec ially indentations and variations in font size that a re vis ually quite striking- disturbing and potenti ally misleading. I should insist on the word "pote nti all y" in this context. I have no s p ecifi c examples that it is mi sleadin g or how. But, as Spinoza also knew, it is diffi cult to d efend a text agai n st its readers who more often than not w ill "only interpret it perverselY:' 3 Who knows wh at p eople might infer from , say, a redu ced fon t size? As in t h e case with capitali za tion s, I find it preferab le to fo res tall th e p roblem.

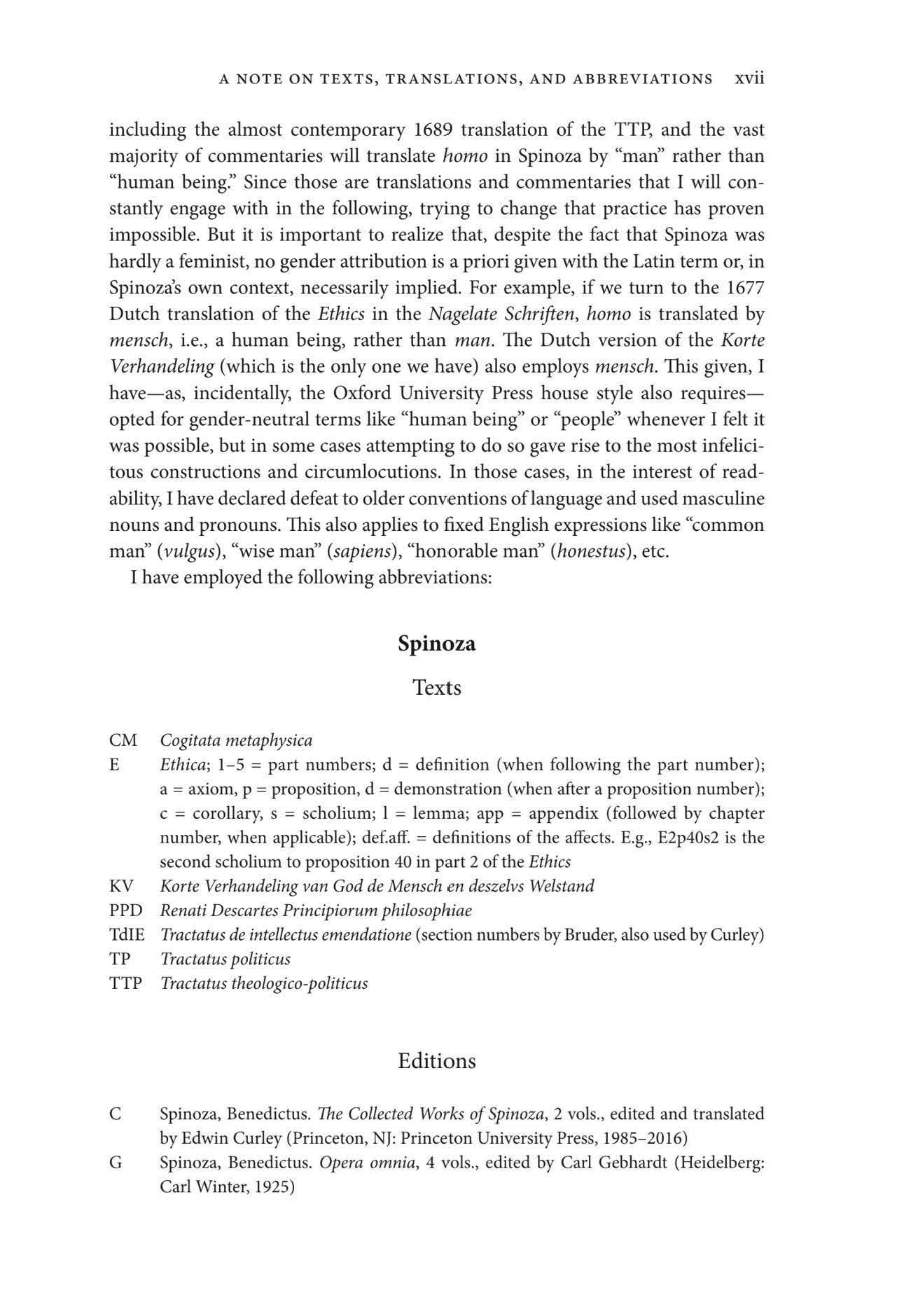

also deviate from C url ey's t ranslations wh en h e re lies on typographical p ec uliarities for co n veyin g term inological dist in c tions. For example, he adds a prime symbol in front of the te rm "power" (' powe r) w h en eve r it translates the Latin potestas, as opposed to "po wer" w itho ut th e p ri m e sym b ol, whic h translates potentia and occasionally vis. 4 Similarly, h e gives both cognitio and scie ntia as "knowledge;' but adds a prime symbol for the latter term ( ' knowledge) . As ano ther instance of such practices, in order to overcome the fact tha t the common tra nslation of th e two Latin t erms sive and vel by th e single term "or" obscures th e fact that the fi rst ( m os t often) conveys an e qui va len ce and the second an alternative, Curley a dds ital ics to th e t erm (or) wh e never it translates seu or sive. 5 I find th ese solutions a bit awkward and have everywh er e supp ressed the prime sym bols/itali cs. In many cases, context makes Spinoza's m ean ing clear enough. W h en I felt th a t i t was not the case and that it made a difference, I have p rov ided the Latin te rm in brackets.

I should in t h at co ntext make an additional note re ga rdin g potentia/potestas. From Anton io Neg ri 's 198 1 LA.nomalia Selvaggia onwards, a substantial Spinoza literature conside rs this distinction essential fo r m a kin g sen se of the political th eories in th e TTP and th e T P, and of the re lat ion b etween them. 6 In the Englishspeaking world, th e reading h as bee n adop ted by Lee Rice a nd Steph en Barb one, Michael H ardt, and m an y others. 7 The distin ction is some times in the com m ent aries rendered in English by givin g potentia as "power" and potestas as "auth ori ty:' Poten tia, the argument goes, signifies th e power esse ntial to individual s, th e ir conatus, while potestas co rres pond s to a more legal autho rity that individ ua ls can transfer to a sovereign power and that a sove re ign po wer c an yield over individuals. D es pite all th e com me ntary, I am un co n vinced that mu ch hinges on the distinction and I h ave not sys tem a ti cally in d icated when Spinoza uses which t erm I have several reasons for takin g that position. First, w hile so m ething like this dist inction is perhaps operative in some passages, 8 Spinoza does not implement it systemati cally or th ematize it explicitly 9 In fac t , it is no t infre quent that h e e mploys th e two terms interch an geably. 10 Second, it is n o t clear to me that the expla n ato r y wo rk d o ne by t his ration ally reconst ruc ted di stinc tion o utweigh s th e interpretive problems it creates. 11 Third, as I w ill sh ow in Ch apter 9, the problems relating to Spinoza's socia l contract th eo r y t h at the analyt ic distin ction is p rin cip a lly d esigned to overcome can b e be tt er d ealt w ith by oth er means. Fo urth, and fin ally, with regard to th e English re nd erin g of potestas, as I sh all argu e in C h a p te r 5, Spinoza has a ri ch th eory of autho ri tas, an d I believe the Englis h term "authori ty" is best reser ved fo r tha t context Ind eed , in many ways, I think we wo ul d do be tter to read Sp inoza's th eo ry of pol iti cal powe r in the co nte xt of m o re class ic (Cicero nian and Gelasian) distin ctions between au thoritas an d potestas/ potentia .

C urley h as put every effort into finding ways of co n sistently translating single t erms, but it is obviously not poss ible to always render a single Latin term by a

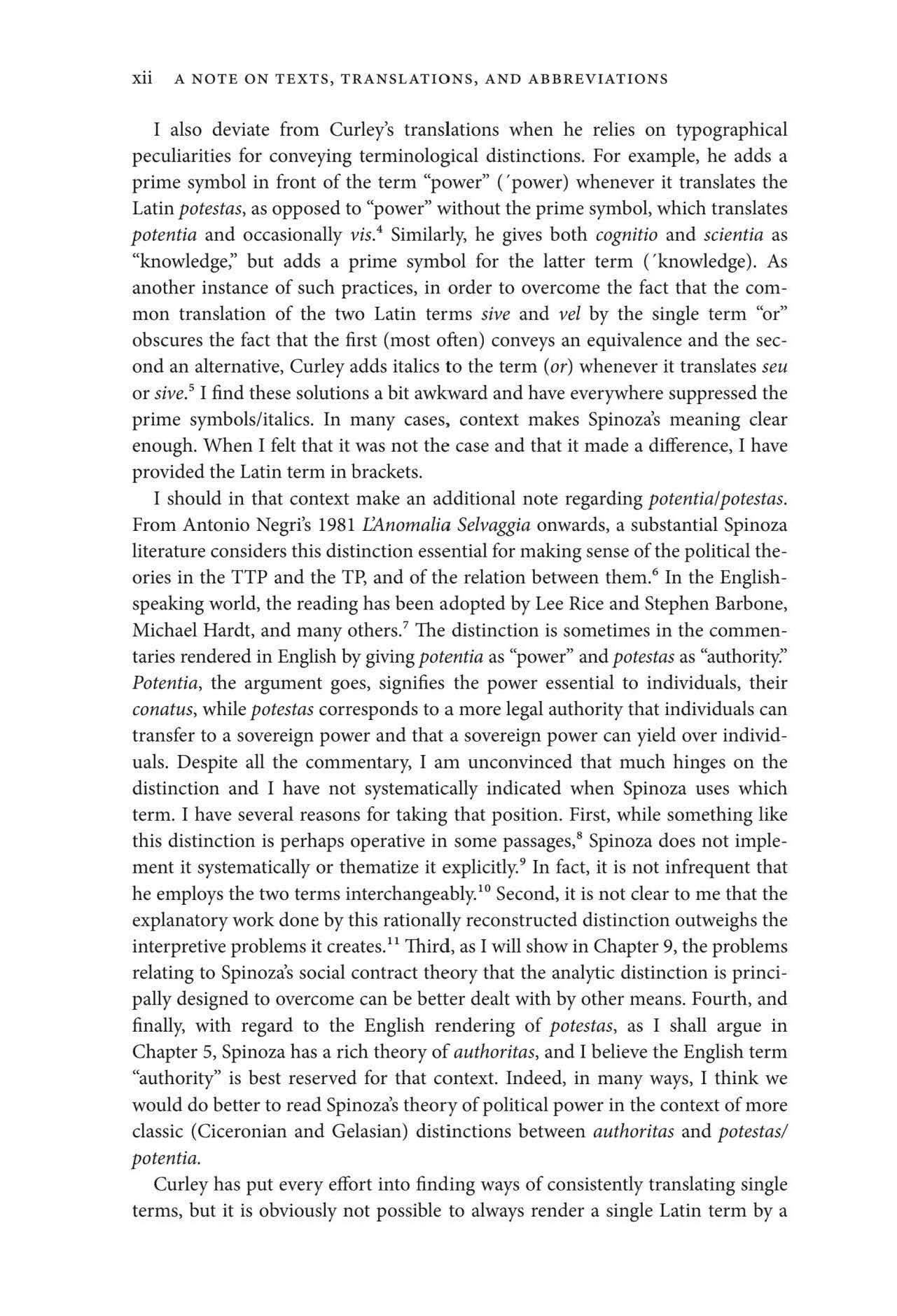

single English translation, or vice versa. I have often been struck by the stylistic and philosophical superiority of his sol utions when confro nted with such choices. In some cases, however, they obscure what I think are central conceptual con n ections. It is, for example, the case when he occasionally translates dogma by "maxim" rather than, as elsewhere, "doctrine;' or sometim es translates the verb amplecti by "to accept" rather than, as he most often does, "to embrace:' At other times, an identical translation of several terms can in vite confusion, for example when th e term "authority" translates authoritas but also so m etimes the intractable term imperium. Finally, in som e cases, C urley's translations suggest conce ptual distin ctions that may or may not be implied but that in any case are not discernibl e via Spinoza's own term inolog y, as for example when, in the TP, h e tran slates the single Latin term temp/um alternately by "ho use of worship" or "temp le;' or, in the TTP, he gives the single Latin term plebs sometimes by "ordinary people" and so metimes by "mob:' Often I have not found b ett er alternatives and let Curley's choices stand, but I have found it worthwhile to point them o ut. Generally, addressing such issu es of translation has been important for this study where the consideration of lexical fields, their internal constitution within Spinoza's te xts, and their external connections to other, contemporary texts play a de cisive role. It should, however, be stressed th at my own choices of translationwhether they di ve rge from Curley or not-are often moti vated by this text- and term- oriented methodology th at other readers of Spinoza might not find palatable It also explains why I so frequently indicate in brackets th e original terms employed by both Spinoza an d other philosophers.

I also need to take note of a few additional terms that pose problems and that call for some comments, regardless of whether I h ave deviated from Curley's choice of translation or not.

Curley translates Spinoza's key virtue charitas as "loving -kindness:' I have everywhere changed it to "ch ar ity;' which is also the choice of the firs t English transla tion of the TTP of 1689, usually attributed to the English Deist, Charles Blount. 12 C urley takes his cue from the fact that, in a particular passage in TTP XIII, charitas translates the Hebrew term chesed w hich, fo llo wing a practice adopted by certain English Bible translators, should be given as "lovingkindness." 13 But I do not see Spinoza as addressing him self to Hebraists or Bible translators but mostly to a free-thinking non- academic au di ence, principally of Christian extraction. And I think, in particular for understanding the so-called doctrines of uni versal faith, one of which stipulates that "the worship of God and obedience to him consist only in justice and charity, or in love toward one's neighbor Uustitia, & Charitate, sive amore erga Proximum];' 14 that it is important to maintain everywhere the contextual co nnection to the Paulinian understanding of brotherly love that doubtless would be the principal connotation of the term charitas for Spinoza's intended reader. Curley moreover prefers "loving-kindness" in order to avoid th e assoc iation to charity work in the sense of provid ing h elp to

the n eedy. 15 And ce rtainly, Spinoza was no fan of giv ing alms but fe lt, rather percep tive ly, that "the case of the poor falls upon socie ty as a whole, and co ncerns only the ge neral advantage;' while "the than kfulness which men ... display toward one another is for t he most part a business transaction or [se u] an e ntrapment, ra ther than thankfulness:' 16 Still, as Be th Lord h as sh own in so m e excellent work on Spinoza and economic in equ ality; th e association might not b e quite as inappropriate as Curle y thinks. 17

By contrast, I have followed C urley in translating dogma by "doctrin e;' as opposed to th e more theolo gica ll y co nn o ted "do g m a:' Whi le I a m unmoved by Curley's explicit reason for shunning "dogma" -that it "now fre quently h as the connotation, not prese nt in the Latin , of 'an impe rious or arrogant d eclar ation of opinion' (OED), of uncritical and unjustified acce pta n ce" - it qu ickly became app a rent to m e while writing that usin g "do gma" becam e awkward and artificial in man y co ntexts where an En glish equi va le nt of dogma was necessarily ca lled for. I am, howeve r, not entirely co nfident that I have m ade th e ri ght choi ce, so I will register some of m y concerns here. First, and most importantly, it makes it so m ewhat difficult to navigate th e lex ical fie ld betwee n the terms dogma (given by Curl ey as "do ctrine;' occasionally "maxim"), doctrina (" teachin g;· but sometim es "do c trine"), documentum ("teaching" or "lesso n"), and documenta docere ("to teach lessons" ). 18 Nex t, in the context of Spinoza's discussion of th e do ct rin es of uni ve rsal faith (jidei universalis dogmata ) in TTP XIV, transla tin g dogma by "do ctrin e" tends to r en der less obvious some relations to th e theol ogical context of Sp inoza's disc ussion. For example, in the translations I have used of Lodewijk Meyer's Philosophia S. Scripurae interpres (by Shirley) or Grotius's Meletius (by Posthumus Meyjes), dogma is everywh e re given as "dogma" in comp a ra ble disc ussions of the foundations of the C hri sti a n fa ith . Spinoza does, ho wever, also occasionally use the express ion dogmata p olitica that we must translate as "politica l doctrines;' and translat ing diffe rently in th e th eological and in the political context would seriously obscure a c rucially importa nt symmetry between th e argumentative stru ctures on the theological and political sides of Spinoza's overall development.

C urle y gives the exp ression summa postestas as "s uprem e 'p owe r:' I have n ot ch anged this ch oice of translation when quoting Spi n oza's text, ap ar t from rem oving the prime sym bol, but it is important to realize-as Curl ey also m a kes clear in his glossary 19 - th at the appropriate translation d epends on what kind of co n text one wants to place Spinoza in, wh eth er one wants to coord inate with seventee nthcentur y translations or co nte mp orary translations and c riti cal editions, and so on . For example, th e 1689 translation of th e TT P gives summa potestas as "sovereign power"; Hobbes uses summa potes tas to translate th e English "sovereign" in the 1665 Latin L eviathan; th e current critical editi o n of Grotius's D e imperio summarum potestatum circa sacra gives su mma po testas as "supreme power"; etc In m y own commentar y, I often re nder the expression by th e hy brid "sovereign

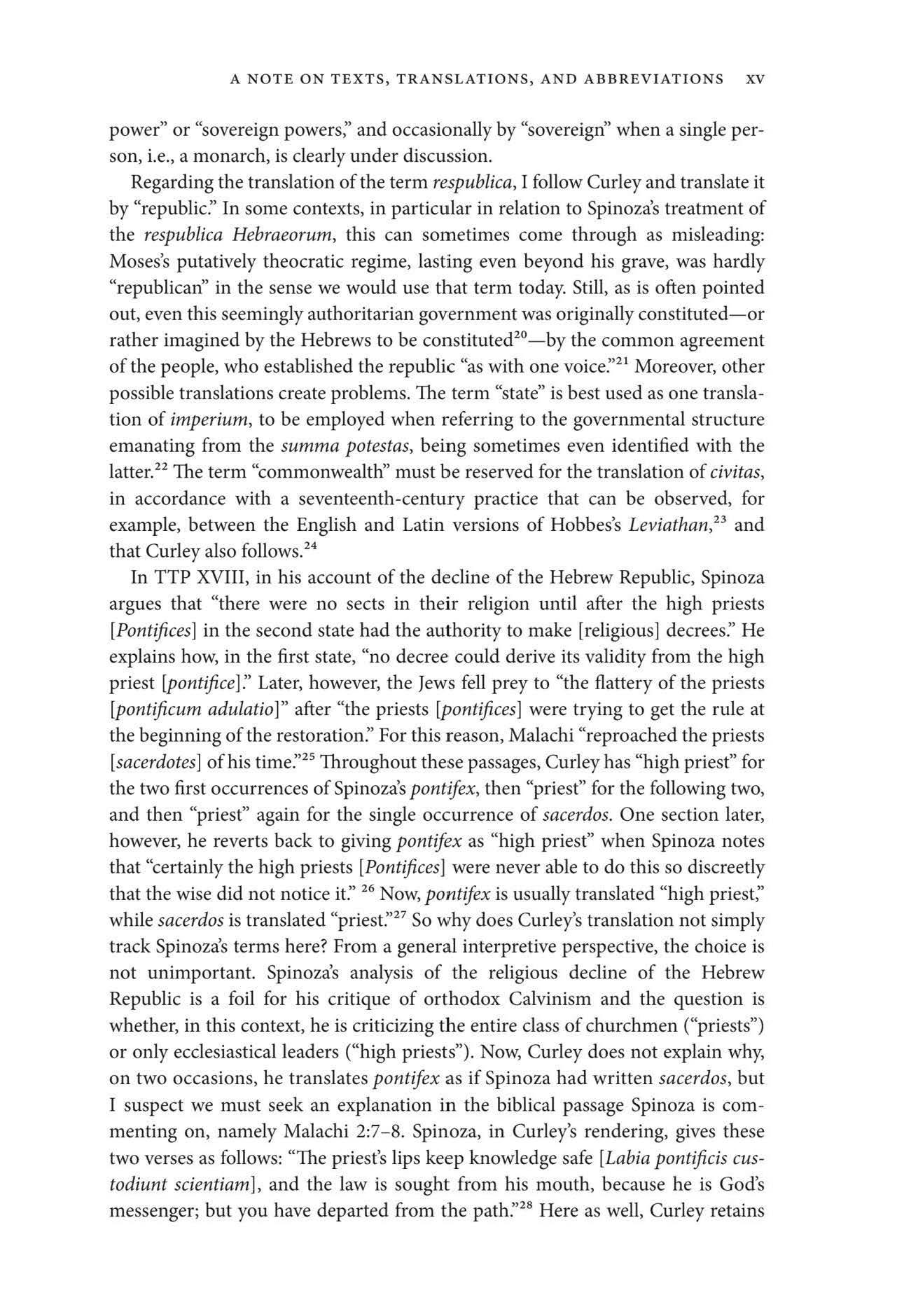

p ower" or "sovereign powers;' an d occasionally by "sovereign" when a single perso n , i .e., a mon arch , is clearly und er discussion.

Regarding the translation of th e term respublica , I follow Curley and translate it by "republic:' In some con texts, in p a rti cular in relation to Spinoza's t reatment of the respublica Hebraeorum, this can sometimes come through as misleading: Moses's putatively t he ocratic regime, lasting eve n beyond his grave, was hardly "re p ubli can" in th e sense we wou ld use that term t o d ay. Still , as is often p ointed out, eve n this seemingly authoritari an govern ment was originally constituted-or rather imagined by th e Hebrews to be con stituted20 - by the common agreement o f th e people, who es tablished the republic "as with one voice:' 21 Moreover, other possible translations c rea t e problems. The term "state" is best us ed as one tra nslati on o f imperium, to be employed when r efe rrin g to the govern m e ntal structu re e manating from the summa potestas, being sometimes even id entified with the latter. 22 The term "com m onwealth" must be reserved for the translation of civitas, in accordance w ith a seventeenth-centu ry p rac ti ce th at can be observed, for example, between the English and Latin vers ions of Hobbes's Leviathan, 2 3 and th at Curley also follows. 24

In TTP XVIII, in his acco unt of the d ecline of the Hebrew Repu blic, Spinoza a rgues th at "the re we re n o sects in their religion until afte r th e high priests [Pontifices] in th e seco nd state had the authority to make [religiou s] decrees:' He explains h ow, in the first s tate, "no decree co uld derive its validity from t he high priest [pontifice]:' Later, h owever, the Jews fell prey to "the flattery of the priests [pontificum adulatio ]" after "the priest s [pontifices] we re trying to get th e ru le at th e beginning of th e restoration:' For this reason, Malachi "reproached t he priests [sacerdotes] of his t im e:'2 5 Throughout these p assages, Curley has "hi gh priest" for the two first occ urre nces of Spin oza's pontifex, then "pries t" for the fo llowing two, and th e n "priest" agai n for the single occurren ce of sacerdos. One section later, h owever, he reve rts back to giving pontifex as "h igh p ri es t" when Spi n oza n otes th a t "cert ainly the high priests [Pontifices) were never able to d o this so discreetly tha t the wise did not notice if ' 26 Now, pontifex is usually translated " high priest;' while sacerdos is translated "pri est:'27 So wh y does C url ey's tran slation not simply track Spinoza's terms h ere? From a general interpretive perspective, th e choice is not unimportant. Spinoza's analysis of the religious decline of the Hebrew Republic is a fo il for his c ritiq ue of orth o d ox Calvinism and the qu estion is whether, in this cont ext, he is criticizing th e ent ire class of churchmen ("priests") or only ecclesiast ical leaders (" hi gh priest s"). Now, Cu rl ey does n ot explain why, on two occas io n s, he tr a n sl ates pontifex as if Spin oza h ad wr itten sacerdos, but I suspect we must seek an expla n at io n in the biblical passage Sp inoza is commenting on , n am ely Malachi 2:7- 8. Spinoza, in Curley's rendering, gives these two verses as fo llows: " The priest's lips keep knowledge safe [Labia pontificis custodiunt s cientiam ], a n d th e law is sough t from his mouth, because h e is God's messenger; but you have departed from the p ath :' 28 Here as well, Curl ey retains

"priest" for Spinoza's pontifex, but it is easier to see why: Spinoza's Latin rendering of Malachi 2:7 is troubling. It is out of tune with both Lati n vers ion s of th e Old Tes tament he u sed: the Junius-Tremellius e diti on has "Quum labia sacerdotis obse rvarent scien ti a m";29 the Vu lga te has "Labia enim sacerdotis c u sto dien t scientiam :' Spinoza's Spanish Bible- th e 1602 Amsterdam edition of the Biblio del Cantaro 30 -onl y h as a perso nal pronoun at Malachi 2:7 (" La Ley d e verdad estuvo en su boca''), but it is co rrela ted with a sacerdos at Malac hi 2: 1. The Heb rew h as :i'01_J, kohen, u sually give n as "priest;' not J;i l rn'.i, kohen gadol, u sually given as " high priest:' Sp in oza's translation is closest to t he Vulga te, but ch anges sace rdos to pontifex. I can only assume th at, on the authority of th e single occurrence of th e term sacerdos we find in Spinoza's text, Curley then makes th e choice to correct both Spin oza's rendering of the verse a nd the directly assoc iated co mmen tary, so th at they are in confo rmity with the e diti ons o f th e Bible Spinoza uses. I think, h oweve r, it is th e wrong call to second -guess Spin oza here and h ave c hose n to give all occ urre n ces of pontifex in his t ext as "high p ri esf' 3 1

C urley translat es Spinoza's acquiescent ia in se ipso - our highes t goo d according to th e Ethics-by "self-esteem:>n His choice is governed by the fact that Spinoza is using Cartesian ter minology and that, in Spinoza's Latin edition of Descartes's Passions de l'ame, acquiescentia in se ipso translates th e French sa tisfaction de soy mesme. 33 C url ey do es, however, recognize that other options a re acceptable and offers a lternati ve translations for oth e r, closely related n otio n s . 34 For example, at E5p27 and E5p32d, h e tr ans lates mentis acquiescentia by "satisfact ion of mind "35 and vera animi acquiescentia a t E5 p42s as "tru e p eace of mind:' At E4app4 and ESp lOs, h e tr an slates animi acquiescentia by "satisfa c tion of th e mind :'36 H e gives this sam e expression as "peace of mind" in th e TTP. 37 Wh ile many co mmentators maintain C url ey's choi ces, the y h ave occasion ed so m e scholarl y discussion. 38 Most re cently, Clare Carlisle h as argued that Curl ey's tr ansla ti on "distorts and obscu res Sp in oza's account of th e hu m a n goo d ;' partly b eca u se it re nd ers the lexical field co n stitu te d aro und th e term acquiescentia indiscernible, arguing that it o bfuscates the connotation s to stillness and quietude implied by the Latin. 39 I , for my p ar t , wo uld not go quite th at far, b ut I have been tro u bled by the p ossible confusion the translation creates with th e passion called edelmoedigheid in the KV, a D u tch term p erhaps mos t naturally tran slate d as "ge nerosity;' "nobility;' or "mag nanimity;' but that C urley (advisedly) gives as "legitimate self- es teem:'40 While close con n ectio n s clearly exis t b etween them, there is no way t hat edelmoedigh eid can b e considere d as straightforwardl y eq uiv alent to acquiescentia in se ipso a nd I find it potentially misleading t o translat e th em both as "s elf-est eem:' 4 ' I th e refore op t for "self-co ntentment" as a safer translation of acquiescentia in se ipso. 42

Finally, I sh o uld m ake a note ab out ge nd e red pronouns an d h ow th ey a re u sed th ro ugh out this study Most En glish t ranslatio n s of Spin oza's principal wor ks,

includin g the almos t co ntemporary 1689 translation of the TTP, and th e vast majority of commentaries will translate homo in Spinoza by "man" rather than "human being:' Since those a re translations and commentaries that I will constantly engage with in the following, t r ying to c han ge that practice has proven impossible. But it is important to realize that, despite the fact that Spinoza was hardly a feminist, n o gende r att ribu t ion is a priori give n with th e Latin term or, in Spinoza's own cont ext, necessa rily implied. For exampl e, if we turn t o the 1677 Dutch t ransla tion of th e Ethics in the Nagelate Schriften, homo is translated by mensch, i.e ., a hu man b e ing, rather than man. The Dutch vers ion of the Korte Verhandeling (which is th e only one we h ave) also em ploys mensch. This give n , I h ave - as, inc ide ntall y, th e Oxford U niversity Press h ouse style a lso requiresopted for gender- n eut ral terms like " hum an being" or "people" wh eneve r I felt it was possible, but in some cases attempting to d o so gave rise to the most infelicito us co n structions a n d circumloc utio n s. In th ose cases, in th e interest of reada bility, I h ave declared defeat to olde r conventions oflangu age a nd used masculine nouns and pronouns. This also app li es to fixed En glish expressions like "com m on man" (vulgus), "wise man" (sapiens), "honorable man" (honestus), et c.

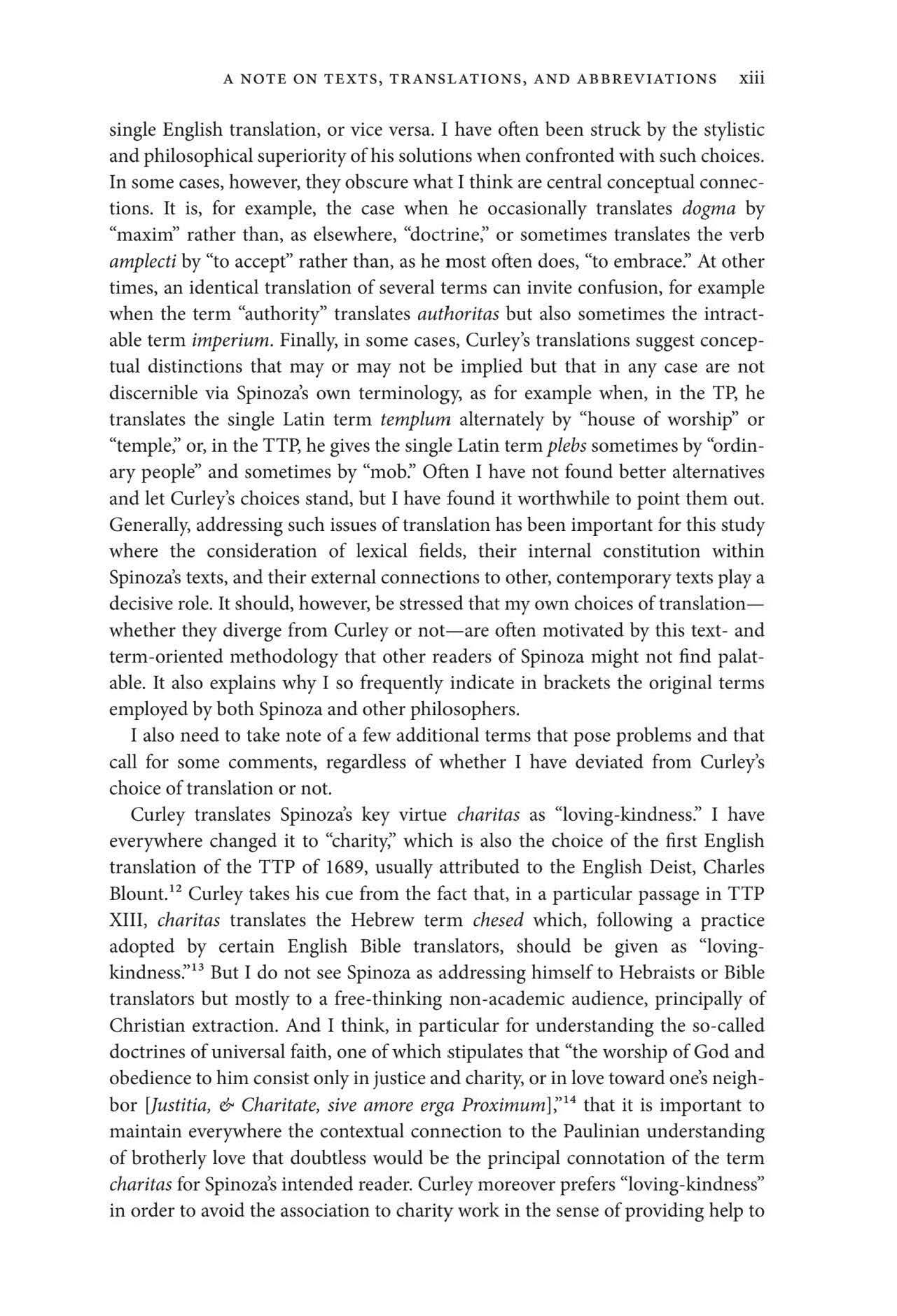

I h ave employe d the following abbreviations:

Tex t s

CM Cogitata metaphysica

E Ethica; 1- 5 = part numbers; d = definition (w hen following t h e p ar t number ); a= axiom, p =propos ition, d =de m onstration (whe n afte r a proposit ion number); c = co rollar y, s = scholium; I = lemma; app = appendix (followed by c hapte r number, when applicab le); def.aff. = definitions of the affects. E.g., E2p40s2 is the second scholium t o proposition 40 in p ar t 2 of the Ethics

KV Korte Verhandeling van God de Mensch en deszelvs We/stand

PPD R enati Descartes Prin cipiorum philosophiae

TdIE Tractatus de intellectus emendatione (section n umbers by Bruder, also used by Curley)

TP Tractatus politicus

TTP Tractatus th eologico-politicus

Editions

C Spinoza, Benedictus. The Collected Works of Sp in oz a, 2 vols., edited and translated b y Edwin Curley ( Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1985-20 16)

G Spinoza, Benedictus. Opera omnia, 4 vols., edited by Carl Gebhard t (Heidelberg: Carl Winter, 1925)

Spinoza

Descartes

AT Oeuvres , 12 vols., translated by Charles Adam and Paul Tannery (Paris: Cerf, 1897 - 1909)

CSMK Th e Philosophical Writings of Descartes , 3 vols., edited by John Cottingham, Robert Stoothoff, Dugald Murdoch, and Anthony Kenny (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985- 91)

1 Introduction

The End of the Republic

When the Amsterdam municipality in 2008 decided to erect a monument for Spinoza (1632–77) near the city hall at Zwanenburgwal, they chose to engrave onto the pedestal the quote they presumably believed would best capture Spinoza’s lasting philosophical legacy and contribution to the history of Dutch political thought. It is a short phrase that can be found in chapter XX of his 1670 Tractatus theologico-politicus (Theological-Political Treatise, hereafter TTP) according to which “the end of the republic is really freedom” or, as Spinoza writes in the original Latin, finis reipublicae revera libertas est.1 The philosopher was thus, by reference to the final chapter of his treatise, honored as someone who had primarily defended freedom and who saw freedom as the noblest aim of society. However, some seventeen chapters earlier in the same book, Spinoza makes an equally unambiguous, but seemingly entirely different, claim about the aim of the state, namely in chapter III when proclaiming that “the end of all society and of the state . . . is to live securely and conveniently [finis universae societatis, & imperii est . . . secure & commode vivere].”2 Spinoza writes this in the specific context of a discussion of the ancient Hebrew Republic, while explaining how God’s promise to the Patriarchs did not involve any particular privilege of the Jewish people, or imply that they were a chosen people in any strong sense, but only that obedience to the law would bring “continual prosperity.”3 He makes it clear, however, by adding that he intends to “show [this] more fully in what follows”4 and by, later, in TTP XVII, realigning his thinking with the republican slogan drawn from Cicero, Salus populi suprema lex est,5 that his analysis in TTP III is not limited to the particular context of the Hebrew Republic but has a general application, just as that other phrase in TTP XX.

So what was, in fact, the aim of the republic for Spinoza? Was it freedom or was it security? One important first step toward answering that question involves realizing that the phrase engraved on the Spinoza monument was not originally conceived as a standalone motto. It is extracted from a longer passage and its meaning governed by the immediate context in which it occurs. Hence, in the engraving on the pedestal, a word is omitted, indicated by three suspension points in the Latin rendering of the phrase above, namely the conjunction ergo. Spinoza in fact wrote: “So [ergo] the end of the republic is really freedom.” This inconspicuous word, ergo, is important because it invites us—in fact, obliges us—to

Spinoza and the Freedom of Philosophizing. Mogens Lærke, Oxford University Press (2021). © Mogens Lærke. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780192895417.003.0001

consider what precedes the phrase in Spinoza’s text. Moreover, it also suggests that we should take that preceding passage as something that, for Spinoza, could be described adequately by the term “freedom.” And what that preceding passage describes is how the state’s role with regard to its citizens is “to enable their minds and bodies to perform their functions safely, to enable them to use their reason freely, and not to clash with one another in hatred, anger or deception, or deal inequitably with one another.”6 Therefore, as becomes clear when correlating the two passages, if freedom and security, i.e., safety, are both the aim of the state, it is because the latter is an integral part of the former, or that security is just one component of a more complex conception of freedom that also incorporates the use of reason, equity, and the absence of hatred, anger, and deception.

The argument of the present work is that this complex conception of freedom also governs the meaning of the notion that Spinoza introduces in the subtitle of the TTP, namely the “freedom of philosophizing,” or libertas philosophandi. My polemical aim is to do away with a still current but I think misguided understanding of the freedom of philosophizing as something akin to a broad legal permission to express whatever opinion one embraces, comparable to a right to “free speech” in the sense it has acquired especially in the American legal tradition and political culture, enshrined in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. How to interpret exactly the First Amendment, especially what kind of speech it covers and what its limits are, is of course an exceedingly complex matter that I cannot undertake to discuss in any detail here. However, I think it relatively uncontroversial to say that, in this tradition, “free speech” is understood as an individual right of citizens that the state honors by abstaining from putting legal constraints upon their speech. Free speech is thus understood in terms of the kind of freedom that Isaiah Berlin termed “negative,”7 paradigmatically stated in Hobbes’s definition of liberty as “the absence of externall Impediments,”8 as opposed to the kind of “positive” freedom as selfdetermination that Spinoza embraces in the Ethics, according to which “that thing is called free which exists from the necessity of its nature alone, and is determined to act by itself alone.”9 Such negatively defined free speech may have its limits; some kinds of speech may not be legally permitted. Still, on this understanding, whether one speaks freely or not is not as such a function of what one says or how one says it, but of whether one is legally allowed to say it or not. What I want to show is that Spinoza’s freedom of philosophizing, by contrast, is entirely predicated on what is being said and how. The collective political freedom of philosophizing in the TTP cannot be identified with the kind of individual ethical freedom whose conditions Spinoza explores throughout the Ethics. But it is still akin to it and the two distinct conceptions of freedom in the TTP and in the Ethics subtly coordinated with each other. The freedom of philosophizing represents a “positive” conception of how to better regulate our mutual interactions in view of collective selfdetermination, not a “negative” legal conception recommending a mere

absence of rules. In fact, whether philosophizing is free or not is not a legal matter at all. It depends on whether those who engage in it interact with honesty and integrity, i.e., whether what they say genuinely reflects what they think and what they think reflects a judgment they can genuinely call their own.

A first important step toward avoiding the assimilation of Spinoza’s conception of the freedom of philosophizing to the legal tradition of free speech is to not confuse the “freedom” (libertas) of philosophizing with what Spinoza speaks of in terms of a “permission” (licentia) to say what we think. This latter term also figures prominently in the TTP, in the title of chapter XX where “it is shown that in a free republic everyone is permitted [licere] to think what he wishes and to say what he thinks.” On the influential reading that I reject, by “freedom of philosophizing” and “permission to say what one thinks” Spinoza basically refers to the same thing, namely a right to speak freely that citizens in a free republic are granted, and as something that can be legally allowed in the same way as it can also, in an unfree republic, be legally denied. In modern scholarship, this approach to Spinoza’s freedom of philosophizing was perhaps first suggested by Leo Strauss in his long article of 1947–8 on “How to Study Spinoza’s ‘Theologicopolitical Treatise’,” reprinted as a chapter in his 1952 Persecution and the Art of Writing.10 Reading Spinoza in this fashion requires that the notion of freedom governing the TTP’s conception of the freedom of philosophizing is entirely distinct from the more considered notion of freedom that he develops in the Ethics. This is, for example, why Strauss insists that Spinoza’s plea for the freedom of philosophizing is “based on arguments taken from the character of the Biblical teaching.”11 The importance of this phrase can perhaps best be measured in terms of what it does not say, or implicitly denies, namely that the freedom of philosophizing, without necessarily being identical to it, is also informed by Spinoza’s positive conception of freedom as selfdetermination in the Ethics.12

Strauss, of course, composed his analysis over half a century ago and much has been said since then to deepen, correct, or refute it.13 Nonetheless, mutatis mutandis, the position remains prominent. The reading was already consolidated and further elaborated by Lewis S. Feuer in Spinoza and the Rise of Liberalism, published in 1958.14 Still, the doubtless most influential—and in many ways insightful—example is Steven B. Smith’s 1997 Spinoza, Liberalism and the Question of Jewish Identity. For him, “the Treatise ought to be considered a classic of modern liberal democratic theory,” a theory which “is based on the model of the free or liberated individual. This individual is free not only in the philosophical sense but in the ordinary sense that comes with liberation from ecclesiastical tutelage and supervision.”15 Faithful to that general framework of interpretation, predicated on an “ordinary sense” fraught with anachronism, Smith goes on to argue that “the great theme of the Treatise is the freedom to philosophize,”16 but provides very little by way of explaining what, exactly, the exercise of that freedom consists in. Instead, he puts considerable energy into

demonstrating that it is secured by granting “individual liberty and freedom of speech”17 and for the rest focuses on the “liberated self” resulting from that.18 A more recent example of a liberalist reading of Spinoza’s freedom of philosophizing can be found in Ronald Beiner’s 2005 Civil Religion, where Spinoza’s freedom of philosophizing simply expresses the conviction that a “liberal society requires a protected space for intellectual freedom.”19 In this way, Beiner claims, the appeal to our “natural right to think freely” in chapter XX represents “the consummated statement of Spinoza’s liberalism”20 where he is “trying to open up more space for individual liberty.”21 I find very little to agree with in these characterizations.

A better, but still problematic, understanding of the relation between Spinoza’s conceptions of the “freedom of philosophizing” and “permission to say what one thinks” is to consider them as two sides of a single, dialectical notion of freedom. Thomas Cook has argued “that in the first instance libertas philosophandi is best understood as negative freedom—i.e. freedom from constraint.”22 This “negative” approach leads Cook to depict the libertas philosophandi as being concerned with assigning the “limits of the sovereign’s power and right” visàvis the citizens of the state. On this understanding, Spinoza’s freedom of philosophizing enshrines a legally protected right of individuals to say what they think and think what they want. Cook, however, then goes on to argue that Spinoza’s concept also “points toward a more ‘positive’ conception that is closer to the freedom of the rational person,” echoing what Manfred Walther has described as Spinoza’s “dialectics of freedom.”23 This twosided, dialectical conception of Spinoza’s freedom of philosophizing shared by Cook and Walther represents, I think, a significant advance from Strauss, Smith, and Beiner’s straightforward liberalist interpretations.24 The problem, as I will argue, is that it fails to capture Spinoza’s systematic distinction between permission and freedom. In fact, there is nothing dialectical about Spinoza’s conception of freedom because the notion of a permission to say what one thinks that he develops in TTP XX is not a core part of his notion of the freedom of philosophizing at all, but an auxiliary notion adjacent to it. It is conceived as a political recommendation not to outlaw free philosophizing, as a necessary but far from sufficient condition of libertas philosophandi. Being permitted to philosophize is certainly not, for Spinoza, equivalent to doing so freely.25 But let me briefly outline in more positive terms the alternative I propose. As I see it, Spinoza’s freedom of philosophizing is not grounded in a legal permission enshrined in civil law but in a natural authority inseparable from human nature. As we shall see in Chapter 5, Spinoza describes free philosophizing in terms of an “authority to teach and advise” closely related to a freedom of judgment that belongs to all human beings in virtue of their humanity. Moreover, free philosophizing is the intellectual activity of a community. By contrast to Descartes’s putatively solitary meditator, persons who philosophize freely in Spinoza’s sense are by definition engaged in an activity relating them to others.26 This is also, as we

shall see in Chapter 4, why Spinoza characterizes free philosophizing as a “mode of speech” or a discursive “style,” a style of “brotherly advice” that he opposes to the commanding style of prophetic revelation. This collective nature of the freedom of philosophizing points to what I take to be its fundamental political signification: the notion enshrines Spinoza’s attempt to theorize a new republican public sphere. In this respect, the position I advocate is not unlike the one put forward by Julie Cooper when, resisting liberalist readings, she argues that “when Spinoza defends freedom of speech, he endorses a mode of democratic citizenship, and an ethos of public discourse.”27 And I agree entirely with Christophe Miqueu when he presents Spinoza’s republican project as one that advances an ideal of “citizenship as collective emancipation.”28

In a nutshell, my view is that the freedom of philosophizing is not for Spinoza an individual civil right but a collective natural authority constitutive of a particular kind of public sphere.29 Its constitution requires that citizens collectively take control of their own free judgment in a way that Spinoza believes can be achieved only through “good education, integrity of character, and virtue.”30 This is why, as I analyze it in Chapter 8, his attempt to establish the conceptual foundations of a republican public sphere is intimately related to a rudimentary program for reform of public education.

Bringing out the richer, positive notion of free philosophizing sketched above is the first aim of the present study. A second aim is a reassessment of Spinoza’s contribution to the modern conception of toleration. Politically, Spinoza’s aim is to show that free philosophizing is not only harmless, but beneficial for the peace and stability of a republic. As he writes in the preface to the TTP, “the main thing” that he “resolved to demonstrate in this treatise” was not only that “this freedom can be granted without harm to piety and the peace of the republic, but also that it cannot be abolished unless piety and the peace of the republic are abolished with it.”31 This conception has, among presentday commentators, earned Spinoza a prominent place among the important and most forwardlooking defenders of “toleration” of the seventeenth century. Spinoza scholars in the Englishspeaking world who have defended that position include Edwin Curley, Jonathan Israel, Michael Rosenthal, John Christian Laursen, and Justin Steinberg.32 Moreover, in the broader literature on toleration, including in very influential historical commentaries such as those by Perez Zagorin, Simone Zurbuchen, Philip Milton, or Rainer Forst, Spinoza consistently figures, along with Locke and Bayle, as one of three paradigmatic tolerationists of the early modern period.33 I have no quarrel with those readings. Spinoza, of course, does not, strictly speaking, have a notion of toleration. The noun tolerantia figures only once in his entire work, in TTP XX, in a context where it is most appropriately translated as “endurance.”34 Even if we include his use of the verbal or adjectival forms of the term, none of them suggest “toleration” in the required sense.35 Still, one could argue that it matters little if

the term is present if only the idea is, and some aspects of Spinoza’s conception of the freedom of philosophizing certainly resonate strongly with later, modern conceptions of toleration.36 His political theory incorporates ideals of peaceful coexistence that, for all intents and purposes, amount to something like a political theory of toleration, stressing, for example, that “men must be so governed that they can openly hold different and contrary opinions, and still live in harmony.”37 Moreover, he describes the suppression of the freedom of philosophizing in ways that today can hardly fail to conjure up the term “intolerance.” He argues fiercely against those who “try to take this freedom [of judgment] away from men” and who seek to “bring to judgment the opinions of those who disagree with them.”38 And he proclaims those who “censure publicly those who disagree” and “persecute in a hostile spirit” to be “the worst men,”39 even to be “antichrists.”40

At the same time, however, when building his theologicalpolitical doctrine, Spinoza also appeals, and gives central importance, to theories that are not today usually associated with doctrines of political or religious tolerance. First, in TTP XIX, he develops an Erastian theory of church–state relations, arguing in favor of giving the state firm control over ecclesiastical matters. But today, after Locke, toleration is most often associated with a political regime that does not subject religious opinions to political control. Second, in TTP XVI, he adopts a contract theory clearly informed by Thomas Hobbes who can hardly be said to represent a beacon of modern toleration in the contemporary scholarly literature. Even those commentators who have most successfully attempted to attribute Hobbes a positive role in the elaboration of the modern conception of toleration—such as Edwin Curley or, more recently, Teresa Bejan struggle to get the theory off the ground, mostly because of the firm control over public worship that Hobbes grants the civil sovereign, limiting toleration to the internal realm of a mute individual conscience.41 As I shall argue in Chapter 11, I concede that there is a small crack in Hobbes’s otherwise hermetically closed theoretical edifice, having to do with his conception of private worship in secret that allows toleration some minimal, additional wriggling room within his basic schema of obligatory external profession and free internal faith.42 But it is hardly enough to make De Cive or the Leviathan the goto place for a positive understanding of modern toleration, and the background of Spinoza’s political philosophy in Hobbes gives some reason to at least question his tolerationist credentials and the overall coherence of his political theory from that perspective. Both these aspects of Spinoza’s theological politics—his theory of ius circa sacra and his apparent Hobbesianism—render it impossible to assimilate his conception of the freedom of philosophizing in any straightforward way to contemporary theories of free speech and toleration in the broadly Lockean tradition, which tends to think about these matters in terms of constitutionally guaranteed individual liberties and the separation of church and state.

Elements of Method

This study is methodologically informed by work I have published elsewhere on the methods, aims, and history of the history of philosophy as a discipline, and I should very briefly give the reader a sense of the programmatic intuitions behind this previous work, of the terminology I have devised in order to implement them, and the bearing they have on the way that I approach Spinoza’s work.43

As I see it, the history of philosophy, as a discipline, is essentially concerned with the reconstruction of the historical meaning of past philosophical texts. It must attempt to strike a difficult balance between systematic and historical considerations, between reconstruction of arguments internally within the texts and inquiry into the historical circumstances and intellectual context of the writing and subsequent reception of those texts, grounded in a principled notion of what such historical meaning amounts to. The text, rather than the author, constitutes the privileged relay between the conceptual structure on the one hand and the historical situation on the other: the text has one foot in the philosophy it signifies, the other in the history in which it signifies. Now, one way—popular among historians of philosophy and intellectual historians alike—of capturing both the systematic and historical aspects of past philosophical texts, and the interaction between them, has been to study them as contributions to historical controversies.44 It is a methodological wagon that I am happy to jump on. I fully agree with Susan James that “works of philosophy are best understood as contributions to ongoing conversations or debates.”45

The controversies within which philosophical texts acquire their meaning are defined partly by an intellectual context, partly by historical circumstances.46 By the intellectual context of a text, I understand a cluster of other texts that this text responds to, or that respond to it, at a given historical moment and under particular historical circumstances. Within that context, these texts communicate in all conceivable ways, by reinforcing, contradicting, dismissing, overruling, correcting, expanding, reappropriating, misconstruing, or confronting each other. In this way, the texts within a given contextual cluster form interpretive perspectives on each other—perspectives that can inform us about the historical meaning of each of them within that specific context. By historical circumstances, I understand the nontextual setting of the text, including the institutional framework, the political situation, sociocultural factors, and so on. My contention is then that the meaning of a past philosophical text can be determined by considering the internal, structured argument of the text as a singular response to a given external context of writing established within particular historical circumstances; in short, by considering the text as a structured contribution to a given philosophical controversy.

This approach, systematically constructed around the past philosophical text, its intellectual context, and the historical circumstances of its reading, has a

bearing on two methodological problems specifically related to the reading of Spinoza’s TTP, both having to do with the nature of his writing.

First, my focus on the text explains the singular importance I give to Spinoza’s words, both to the systematic sense they acquire within the conceptual structure of his arguments and to the resonances they have within the intellectual context and historical circumstances of his use of them. I am particularly interested in the ways that those two aspects of their signification work together—or in Spinoza’s case, often clash—in singular ways so as to bestow upon the TTP a particular historical meaning. Such a terminologyoriented approach, however, presupposes that the TTP is a carefully written philosophical text containing not just carefully thoughtout philosophical arguments, but also a carefully elaborated philosophical language to express them. And this assumption is at odds with at least one prominent commentator on the TTP. According to Theo Verbeek,

every reader of Spinoza’s Theologico-political Treatise (1670) will know that it is a difficult book but will also realize that its difficulties are not like those of, say, the Critique of Pure Reason or the Phenomenology of the Mind. Its vocabulary is not technical at all; nor is its reasoning complicated or its logic extraordinary. If it is difficult it is . . . because one fails to see how things combine; how particular arguments fit into a comprehensive argument; how a single chapter or couple of chapters relate to the book as a whole and how the book relates to Spinoza’s other work.47

This is not a depiction of the TTP and of the difficulties associated with reading it that I can recognize. Verbeek’s evaluation, it seems to me, underestimates the conceptual precision and complex coherence of Spinoza’s argument and, it should be noted, the excellent systematic interpretation of the TTP that follows these introductory remarks in Verbeek’s book belies his own assessment. Spinoza is, on the whole, and especially in his later works—the Ethics, the TTP, and the Tractatus politicus (Political Treatise, hereafter TP)—careful, consistent, and systematic about his use of particular terms, and I shall generally assume that he is, unless there is irrefutable proof to the contrary. Apparent inconsistencies should always be considered an invitation to seek out deeper, more complex patterns, and Spinoza’s text declared genuinely inconsistent or his writing careless only when all other options have been exhausted.

My reading of the TTP thus relies importantly on two methodological assumptions.48 First, I operate with a structural assumption that an established orderly pattern in the use of some term or set of terms—an ordered lexical field, so to speak—constitutes a formal argument in favor of a given interpretation on a par with explicit textual evidence. For example, my entire reconstruction in Chapter 5 of Spinoza’s understanding of “authority” (authoritas) is derived from a review of occurrences and their context of use within the TTP. Spinoza never explicitly

thematizes the term. The same applies to a number of other terms that have systematic meaning on my analysis, including “doctrine” (dogma), “foundation” (fundamentum), “standard” (norma), “to embrace” (amplecti), “integrity” (integritas), “collegially” (collegialiter), and many others. Second, I operate with a systematic assumption that the orderly use of given terms already established in one domain will, in principle, apply to the same terms when employed in relation to other domains as well—a kind of analogia fidei of philosophical text interpretation. As the most important example, my analysis of Spinoza’s contract theory in Chapter 10 relies importantly on the idea that the structure of argumentation underlying his doctrine of a social contract is formally similar to the one underlying his account of the socalled doctrines of universal faith—an idea based on the systematic assumption that Spinoza employs the terms “doctrine” (dogma) and “foundation” (fundamentum) in analogous ways in the political and theological contexts. Without these two methodological assumptions, many analyses in this book will appear merely conjectural.

By insisting on the philosophically careful writing and systematic character of the TTP, however, I do not want to imply that the deepest meaning of the book reduces to the relation it entertains with Spinoza’s systematic philosophy, i.e., the Ethics. Spinoza interrupted his work on the Ethics in 1665 to work on the TTP. The TTP was completed in 1670, after which he returned to working on the Ethics, completing it sometime in 1675.49 The writing of the TTP took place quite literally in the middle of his work on the Ethics. Given this history, considerable correlation and overlap between the two works is only to be expected, and I agree with Susan James that “although these two works vary enormously in style and scope, they are intimately connected.”50 The TTP and the Ethics are, via their common ethical agenda, inseparable.51 Moreover, it does not take much reading in the TTP to realize how often, in individual passages and in the use of specific terminology, Spinoza draws on conceptions also found in the Ethics when elaborating his arguments in the TTP, for example about common notions and knowledge of God,52 the identity of the power of nature with the power of God,53 the necessity of the universal laws of nature,54 the relation between the power of nature and the divine intellect,55 the conception of man as a “part of the power of nature,”56 and so on. The connections are countless.57 Still, as Susan James also stresses,58 it would be a serious mistake to take one book to be the foundation of the other. We will fail to grasp the systematic argument of the TTP if we simply presuppose that its underlying systematic framework has a form similar to that of the metaphysics of the Ethics. The TTP has a systematic character entirely of its own. It is borne out in strikingly precise use of terms and concepts, meticulously elaborated and constructed internally within the text, yet in constant external dialogue both with the Ethics and with the terminology and concepts of other, contemporary writers concerned with similar theological, political, and philosophical issues.

The focus I put on the text and its systematic meaning also has an immediate bearing on a topic much discussed by both supporters and detractors of the socalled “esoteric” reading of Spinoza first championed by Leo Strauss, namely whether and to what extent we should read the TTP “between the lines” in order to gain access to the meaning of the text, understood as Spinoza’s deliberately hidden, but more authentic intentions.59 One important aspect of my textoriented approach is an effort to take seriously an insight which is today a truism among literary scholars but which remains, in practice at least, surprisingly ignored by historians of philosophy. It is that the meaning of a text does not reduce to the intention of its author and that common expressions such as “What Locke wanted to say” or “What Hegel had in mind” refer less to primary intentions of authors than to attributed intentions that are not at the root of the text’s meaning but effects of their interpretation.60 However, by considering author intentions as derivative of text interpretation, a textfocused approach such as mine also tends to mostly neutralize the question of “esoteric” reading. On this level, I fully agree with Jacqueline Lagrée when she suggests that it is “wiser to read the Theological-Political Treatise à la lettre and presuppose that Spinoza writes what he thinks and thinks what he writes, even though he probably does not write all that he thinks.”61 For Lagrée, I suspect, the “wisdom” of taking this approach does not lie in knowing where best to search out an author’s true intentions, but in realizing what it is our task as historians of philosophy to study in the first place, namely the meaning of texts. It obviously makes little sense to look beyond the text to discover what is thought if the text just is, by definition, the place where thinking is effectively produced.62 Those Englishspeaking commentators who have taken Lagrée’s point up for discussion, whether it has been to endorse it (Steven Nadler) or to reject it (Edwin Curley),63 have to some extent failed to appreciate these deeper convictions about the primacy of the text and the derivative nature of authorial intentions. And yet the point is foundational for those French historians of philosophy who, like Lagrée, grew up in the shadow of Martial Gueroult whose method of structural analysis rests on a similar textual imperative.64 On this understanding, to restate Lagrée’s point more bluntly, whether Spinoza the historical person thought what he wrote when he wrote it, or whether he thought something else, is a matter of common psychologist conjecture best left to one side by the historian of philosophy whose focus should be on what is written or not written in the text and on what the intellectual context and historical circumstances of the text can contribute to the reading of it.

The question of strategic writing—including writing involving dissimulation— does, however, return with a vengeance on a second level concerned not with the authorial intention behind a text, but with the attributed intention that an author name comes to represent in the interpretation of the text. An approach like mine that considers texts as contributions to controversies will necessarily attribute a strategic dimension to them. It will always see them as responding and adapting

to other texts that they communicate with, establishing the parameters for an internal play of mutual interpretation among them. The question of strategic writing, then, should not be stated in terms of a distinction between what is on the surface of a text and what is behind it, what is in it and what is not, but in terms of seemingly contradictory strands of argumentation, all placed on the surface of the text and explicitly present within it, but whose reconciliation within a unified interpretive framework requires that we attribute to the author either outright inconsistency or strategic intentions. And on this level, as much as I fundamentally agree with Lagrée’s point when correctly understood, I also agree with Curley that she may have missed an important aspect of Strauss’s argument, which is perhaps less about going behind the text to make it say something other than what it actually says, and more about finding a way to reconcile conflicting strands of what it actually says so as to produce a unified interpretation.65 For it is true that, in Spinoza’s texts, there are both selfreflective statements pointing in the direction of strategic writing and apparent contradictions within the text that can be resolved by appealing to “writing between the lines,” even if Strauss grossly exaggerates those contradictions.66

It is, however, another matter whether we should understand Spinoza’s strategies as parts of such a pervasive art of writing deployed for the purpose of avoiding persecution, governed by an esoteric effort to dissimulate more authentic views, or whether better options exist for explaining their function and construction. I, for my part, find little or nothing in the TTP or the related correspondence strong enough to warrant the assumption that fear of persecution was a significant factor in its composition. In 1665, when Spinoza began writing the TTP, he may have been provoked to undertake it by the “excessive authority and aggressiveness” of the preachers.67 In the event, however, the preachers’ aggressiveness led him to speak his mind with remarkable candor rather than the contrary.68 Moreover, the political conjuncture in 1665 was such that the preachers, no matter how aggressive, had limited means of enforcing their agenda. Except in extreme cases, the public authorities were deeply averse to backing up the orthodox Calvinists with coercive power.69 More importantly, however, I find that understanding Spinoza’s strategies not as attempts to dissimulate but to adapt—to adapt religious terminology to Spinoza’s philosophy in terms of content and, conversely, to adapt Spinoza’s philosophy to religious terminology in terms of form— most often makes for better and more comprehensive explanations of the TTP.70 In fact, Spinoza’s most explicit statement about dissimulation and caution in the TTP is formulated in the context of his broader theory of adaptation. He thus recognizes that accommodating one’s discourse to the mentality of interlocutors can be useful for civil life because “the better we know the customs and character of men the more cautiously we will be able to live among them and the better we will be able to accommodate our actions and lives to their mentality, as much as reason allows.”71

I should already here mention one particularly complex instance of these strategies of adaptation governing Spinoza’s argumentation throughout the TTP. The doubtless most powerful argument in favor of an esoteric reading of the TTP is the exposition of the socalled doctrines of universal faith in TTP XIV. These are doctrines that Spinoza insists people must believe in order to be pious, but many of which, if compared with the position he defends in the Ethics, he arguably considered false. Some attempts have been made to demonstrate Spinoza’s own commitment to some version or interpretation of those doctrines in order to overcome the Straussian conclusion that they are all smoke and mirrors. I am unconvinced that such interpretive reconciliation is necessary, or even desirable, in order to grasp the overall coherence of Spinoza’s philosophical and religious views, or to understand the way that the doctrines constitute a useful theological framework adapted to the mentality of the common man. Instead, in Chapter 9, I offer a reading of the doctrines of universal faith that attempts to overcome these difficulties in another way, by assigning to such doctrines an epistemological status quite different from that of philosophical propositions, but without putting into doubt the kind of practical or functional truth Spinoza in fact attributes to them. Still, despite my resistance to esoteric readings, I will not contest that the TTP is often best analyzed as a strategic piece of writing whose inner tensions are not the result of carelessness, but almost always rhetorical effects of a careful linguistic and argumentative strategy in which the author never loses sight of his prospective “philosophical reader” or, indeed, of those whom he would prefer “to neglect this book entirely” because they would only “make trouble by interpreting it perversely.”72

Outline of the General Argument

Before delving into the interpretation of Spinoza’s text, let me finally provide a brief outline of how my global argument is structured and how the chapters of this book are organized. Putting to one side the introduction in this chapter and the conclusion in Chapter 12, it is constituted by three main chapter blocks. In the first block, formed by Chapters 2 to 5, I attempt to pin down exactly what Spinoza understands by the expression libertas philosophandi. Chapter 2 is dedicated to a study of the historical circumstances and the intellectual context of Spinoza’s conception. I am principally interested in the common meaning and connotations of the expression itself. For Spinoza, the question of the freedom of philosophizing was associated with two distinct controversies. Beginning with the disputes between Italian natural philosophers and the Roman Catholic Church in the wake of Galileo’s condemnation in 1633, the expression itself became inseparable from theologicalphilosophical disputes about academic freedom and the separation of natural science from theology. This was still

the principal meaning of the notion in the quarrels between Cartesian philosophers and Calvinist theologians in the Dutch universities during the middle and later decades of the seventeenth century. As I show via an analysis of Spinoza’s brief exchange with Ludwig Fabritius regarding a university position in Heidelberg that the philosopher declined, Spinoza widened the scope of the expression, bringing it into contact with another controversy regarding freedom of religious conscience going back to the early years of the Dutch Republic in the later sixteenth century, but which constantly returned in different guises throughout the entire seventeenth century. I argue that it was Spinoza who first managed to bring these two conceptions of academic freedom and freedom of religious conscience together under a single, systematic conception of libertas philosophandi.

Chapter 3 contains a more text and termoriented analysis of the term “philosophizing” and the meaning it acquires within the argumentative economy of the TTP. I argue that by “philosophizing” we should not understand “to do philosophy” in a narrow sense, but a broader activity—an argumentative style—tied to the use of the natural light common to all and of right and sound reason. It includes not just adequate deductions from certain premises and legitimate inferences from true definitions, but also reasoning from experience and certain principles of interpretation; not just rational analysis of truth, but also historical inquiry into meaning and sound judgment regarding authority. The chapter lays down the groundwork for what I shall argue later, to wit, that when recommending that the state should grant citizens the permission to philosophize freely, Spinoza had something considerably broader in mind than just allowing natural philosophers to pursue their studies without interference from the theologians. The chapter constitutes the systematic counterpart to the historical argument already developed in Chapter 2.

Chapter 4 focuses on chapter XI of the TTP where Spinoza offers an analysis of the Apostles’ Letters in the New Testament. On his analysis, the Apostles use a “style” or “mode of speech” in their Letters which is argumentative, candid, nonapodictic, and egalitarian. Contrasting it with the prophetic command used by the Apostles when they spoke publicly as prophets, he also defines the Apostles’ epistolary style in terms of giving mutual “brotherly advice.” This style, I argue, forms a veritable paradigm of how to engage in free philosophizing. In this chapter, I also show how, by conceiving the collective exercise of the freedom of philosophizing in terms of mutual teaching and the open sharing of knowledge among noble minds, Spinoza draws on common, classical ideals of intellectual friendship.

Chapter 5 studies the kind of authority that free philosophizing is associated with. Who has the authority to give brotherly advice and what kind of authority does such advice come with? In order to answer these questions, it is necessary to reconstruct Spinoza’s—largely implicit—theory of authoritas which includes numerous both genuine and spurious kinds, including prophetic, scriptural,