Introduction

This book is about a female philosopher who lived in a remarkably dynamic and exciting time in history, namely, the fourth century ce, a time when the Roman world was undergoing remarkable political, cultural (in particular religious), and even economic changes. The change that most people focus on is the slow Christianization of the Mediterranean and various kinds of responses from representatives of traditional polytheisms. We encounter our subject, Sosipatra of Pergamum, in one such response, namely, the Lives of the Philosophers and Sophists (VS for short) by Eunapius of Sardis.1 In this work, the author traces a number of intellectual lineages in which he was himself embedded, the primary one being a lineage of ritually oriented Platonic philosophers associated with Iamblichus of Chalcis (c. 245–c. 325 ce), a third-century thinker whose own intellectual roots can be traced back to the “father of NeoPlatonism,” Plotinus (c. 204–270 ce). It is in Eunapius’s tracing of this lineage that we meet Sosipatra.

Ancient sources about women’s lives are exceedingly rare. Outside of Christian martyrologies and hagiographies, they are even rarer. Hence, the relatively long biographical account of Sosipatra is a true exception and a real treasure for the attention it pays to this quite remarkable woman. Eunapius devotes almost as much space to her narrative as to his teacher Chrysanthius’s story, whose account is the longest

1. I rely on the critical edition of the Lives by Richard Goulet: Eunapius, Vies de philosophes et de sophistes, Collection des universités de France. Série grecque, 508 (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2014). All quotations from the sections pertaining to Sosipatra (6.53–96) are from Robert Nau’s translation. Quotations from other passages in the Lives will make use of the Loeb translation: Wilmer Cave Wright, Philostratus and Eunapius: The Lives of the Sophists (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989).

Sosipatra of Pergamum. Heidi Marx, Oxford University Press (2021). © Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190618858.003.0001

in the collection. But despite this relative surfeit of riches, his account of Sosipatra’s life presents modern readers hoping to learn something about women’s lives in Late Antiquity with a number of difficult, and in some instances intractable, challenges. Some of these are associated with the critical differences between modern biographical and historiographical standards and expectations and the conventions of ancient “non-fiction.” And some of these challenges are further compounded by the fact that we have a man writing about a woman, even if in a laudatory and celebratory fashion. But these challenges are themselves pedagogically useful. They tell us something about history; they serve as an opportunity to understand past worlds and worldviews. And it is in this spirit of opportunity that this book sets out to give an account of Sosipatra’s life within its sociocultural, political, and geographical context. It is a task well worth undertaking, because even if we fail, in the end, to encounter the living, breathing historical figure as she really was, we will have understood a great deal about a number of things. These include what the life of an elite woman might have been like in the fourth century ce; what opportunities she had and choices she could make on the basis of her status and gender; how male writers deployed female figures in their works to further their own intellectual agendas and projects of self-fashioning; how professional lineages were constructed and contested; and how non-Christian intellectuals sought to establish and maintain their places in the changing social and religious landscapes of Late Antiquity.2

My working assumption is that even if Eunapius did not give an account of Sosipatra’s life that meets today’s standards for “factual accuracy,” he told the story of Sosipatra’s life in a manner that was appealing and convincing by the biographical standards and conventions of his day, and these standards themselves are of interest to historians of the ancient past. Eunapius’s biographical work can best be thought of as a form of serious entertainment for late ancient intellectuals. It is certainly concerned with “truth,” but not in the sense of historical fact as we think of it. Rather it seeks to convey moral truths and ideological principles in part by presenting idealized images of intellectuals as holy men and

2. For an extensive discussion of this latter question, see Patricia Cox Miller, “Strategies of Representation in Collective Biography: Constructing the Subject as Holy,” in Greek Biography and Panegyric in Late Antiquity, ed. Tomas Hägg and Philip Rousseau, Transformation of the Classical Heritage (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 209–54.

women.3 In other words, it is important to consider the kind of “ideological work” these narratives do. Instead of unquestioningly accepting that Sosipatra was a “powerful and spiritually gifted woman who once lived and taught in late fourth-century Pergamum,” we need to be “mindful as to how Eunapius constructed her as a character within the specific genre of late antique philosophical bioi” (i.e., lives or biographies).4 This book will engage with these very questions in its telling of the story of Sosipatra’s life.

Sosipatra’s Life in Brief

This book includes a new translation by Robert Nau of the passages in the Lives that relate to Sosipatra’s story (see Appendix). Nonetheless, it is helpful to review some of the important events and highlights of her biography at the outset. We do not know precisely when Sosipatra was born, nor do we know when she died. It is difficult, based on the information Eunapius gives regarding her and others connected to her, to give anything like precise dates for her birth and death. Based on a number of details in his larger account, however, it seems likely that she was born in the early decades of the fourth century and may have belonged to the “final pagan generation,” namely, those “pagans” who were born in the 310s and grew up and were educated during the reign of Constantine.5 By the “final pagan generation,” we mean “the last group of elite Romans, both pagan and Christian, who were born into a world in which most people believed that the pagan public religious order of the past few millennia would continue indefinitely.” In other words, they were the last Romans who “simply could not imagine a Roman world

3. There is, at this point, a substantial secondary literature on the idea of the holy man and woman in Late Antiquity, in particular pertaining to philosophers who are presented as god-like or divinized. See for instance, Polymnia Athanassiadi, “The Divine Man of Late Hellenism: A Sociable and Popular Figure,” in Divine Men and Women in the History and Society of Late Hellenism, ed. Maria Dzielska and Kamilla Twardowska (Krakow: Jagiellonian University Press, 2013), 13–28; Peter Brown, “The Rise and Function of the Holy Man in Late Antiquity,” Journal of Roman Studies 61 (1971): 80–101; and Garth Fowden, “The Pagan Holy Man in Late Antique Society,” Journal of Hellenic Studies 102 (1982): 33–59.

4. Nicola Denzey Lewis, “Living Images of the Divine: Female Theurgists in Late Antiquity,” in Daughters of Hecate: Women and Magic in the Ancient World, ed. Dayna S. Kalleres and Kimberly B. Stratton (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 275.

5. Edward Jay Watts, The Final Pagan Generation, Transformation of the Classical Heritage, 53 (Oakland: University of California Press, 2015), 6.

dominated by a Christian majority.”6 This likely describes what would have been Sosipatra’s outlook. However, by the time Eunapius is writing the Lives at the end of the fourth century, it is clear he did not participate in these earlier beliefs. It is also highly plausible, as Sosipatra outlived her three sons, all of whom reached adulthood, that she lived through the brief reign of the Emperor Julian (361–363 ce) who started life as a Christian but became an enthusiastic restorer of traditional polytheistic worship. Although it is rare to find reference to Sosipatra in standard historical accounts of this period, Julian continues to capture the imagination of non-fiction and fiction writers to this day.7 In his novel Julian, Gore Vidal does have the future emperor attend dinner with Sosipatra in his youth, but Vidal presents her as a frivolous “magician” or soothsayer of sorts and not as a true philosopher.8 Eunapius does not tell us if the two ever met, but Sosipatra was the teacher of Julian’s own philosophical instructor and close advisor, Maximus of Ephesus. And as we will see, on Eunapius’s account, it is Maximus who is the less substantive figure in terms of philosophical expertise and assimilation to divinity. According to Eunapius, Sosipatra was born near Ephesus in the region of the Cayster River (the “little Meander”).9 This likely means that her family had ties to the city of Ephesus, which was one of the most important centers in late ancient Asia Minor (the west coast of modern day Turkey) (see Figure 1.1). Her family was very wealthy, and Sosipatra herself was, like most female subjects of hagiographical accounts and Greco-Roman novels, marked from childhood as especially bright, beautiful, and decorous.10 When she was but five years old, so the story goes, two older men clothed in animal skins arrived on the estate as

6. Watts, The Final Pagan Generation, 6.

7. As Susanna Elm notes: “From the moment of his death, on a Persian battlefield, in 363, to today there has been hardly a year when he was not the subject of a written work in one genre or another.” Susanna Elm, Sons of Hellenism, Fathers of the Church Emperor Julian, Gregory of Nazianzus, and the Vision of Rome, Transformation of the Classical Heritage 49 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 3.

8. Gore Vidal, Julian, reprint ed. (New York: Vintage, 2003), 72–77. Vidal’s treatment is reminiscent of earlier scholarly assessments of many late Platonist philosophers after Plotinus, assessments that tended to be dismissive and critical of the direction his successors took in focusing on ritual. E. R. Dodds is the best exemplar of this perspective; see, for instance, E. R. Dodds, The Greeks and the Irrational (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1951). Subsequent work has challenged his dismissal of late Platonism as superstitious and devolved. For a discussion of scholarly attempts to rehabilitate philosophers such as Iamblichus, see Heidi Marx-Wolf, Spiritual Taxonomies and Ritual Authority: Platonists, Priests, and Gnostics in the Third Century C.E. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 60–62.

9. Eunap., VS 6.54.

10. Eunap., VS 6.54.

Map of Asia Minor in the fourth century ce.

Figure 1.1.

itinerant workers. They were given a position tending vines, and at harvest time, the yield was so extraordinary that Sosipatra’s father invited them to dine with him.11 The strangers were so captivated by Sosipatra, that they made her father a deal that if he would leave her alone with them on the estate for five years, they would educate her with similarly remarkable effects. And so her father beat a hasty retreat lest he miss this opportunity to benefit his daughter by his absence.12 When he returned after the allotted five years, the results were remarkable indeed. He was convinced she was a goddess.13 When asked who they were, the old men reluctantly revealed that they were initiates in Chaldean lore (i.e., ancient Babylonian wisdom with a particular focus on ritual and astrology).14 To a contemporary audience, this would have meant that they were experts in the divinization of the soul. Upon their departure from the estate, they initiated Sosipatra into their mysteries and entrusted their books to her, explaining that they would be traveling to the “Western Ocean” for a time.15 In the cosmological understanding of late Roman theories of divinization, this indicated that they were no mere mortals but rather some sort of intermediary spirits, possibly daemons or heroes. In antiquity, the realm between the highest gods and the realm of humans was richly and densely populated by many such spirits, some of whom acted as messengers (angeles), some who were cosmic administrators (good daemones), and some who were the divinized progeny of humans and gods (demigods or heroes). All of these spirits could take on human form or inhabit human bodies. And in some accounts, they would do so as part of the cycle of reincarnation. After the departure of her teachers, Sosipatra was allowed to live her life as she saw fit on her father’s estate. From this time on, “she did not have other teachers, and yet she had on her lips the books of the poets, philosophers, and orators,” all of which she understood fully and with ease.16

When it suited her, Sosipatra decided to marry. She chose Eustathius, another subject of Eunapius’s narrative, the only man worthy of her.17 When they were wed, she prophesied that he would live five more years,

11. Eunap., VS 6.55–57.

12. Eunap., VS 6.58–61.

13. Eunap., VS 6.64–67.

14. Eunap., VS 6.67. For Eunapius’s audience, this would have signaled that Sosipatra’s teachers were “theurgists”—a term we will define shortly.

15. Eunap., VS 6.70.

16. Eunap., VS 6.75.

17. Eunap., VS 6.76.

that they would have three sons together, and that his soul, upon death, would rise as high as the orbit of the moon. She also prophesied that her own soul would rise even higher. These ideas concerning whence souls come and whither they go are part of some schools of late Platonic theology. Commentators, drawing on Platonic myths such as the fall of the soul in the Phaedrus, or the Myth of Er in the Republic, came up with theological explanations for how and why souls were embodied and how they could eventually free themselves from the constraints of this predicament. Eunapius uses Sosipatra’s prophecy here to signal how superior she is even to her husband. All of this, of course, transpired as foretold.18 Upon Eustathius’s death (or possibly upon his departure, as we will discuss later), Sosipatra settled in Pergamum, where she led a school of philosophy in her home. Her friend Aedesius, Eustathius’s former teacher and successor to Iamblichus’s school, administered her affairs and helped to educate her sons. He had his own school in Pergamum and they shared students.19 As mentioned earlier, one of her students was Maximus, who would eventually become the Emperor Julian’s teacher in philosophy and theurgy (a form of philosophically inflected ritual practice and expertise), as well as his close advisor. Maximus helped her at one point by performing a ritual to avert a love spell cast on her by her kinsman, Philometer.20

In addition to teaching standard Platonic subjects—including the embodiment and ideal life of the soul and the role philosophy plays in attaining it—Sosipatra became famous for her prophetic activity, which occurred as the result of divine guidance or even possession. Eunapius refers to it as a kind of bacchic frenzy.21 She was especially adept at what we might call “remote viewing,” seeing events as they happen elsewhere.22 This ability further convinced her students and associates that she was, in fact, some sort of divinity. Of her three sons, only one was worthy of Eunapius’s attention, namely, Antoninus, who settled at the Canobic mouth of the Nile, living in a temple of Isis and devoting himself to philosophy and to the rites associated with the temple.23 The

18. Eunap., VS 6.77–79.

19. Eunap., VS 6.80–81.

20. Eunap., VS 6.82–89.

21. Eunap., VS 6.91.

22. Denzey Lewis, “Living Images of the Divine: Female Theurgists in Late Antiquity,” 277.

23. For a helpful discussion of the details of Antoninus’s life included in Eunapius’s Lives, see David Frankfurter, “The Consequences of Hellenism in Late Antique Egypt: Religious Worlds and Actors,” Archiv Für Religionsgeschichte 2, no. 2 (2000): 186–88.

family’s story ends with Antoninus’s prophetic vision of the destruction of the Alexandrian temple of Serapis, which happened during the reign of Theodosius, shortly after Antoninus’s death.24

Eunapius of Sardis and the Purpose of His Lives

Eunapius of Sardis was a well-educated, well-connected rhetorician who lived in Roman Lydia (a Roman province located in what is now Western Turkey) in the latter half of the fourth century. The date of his birth is a matter of some debate, but for our purposes we can fix it sometime between 345 and 349 ce.25 He was trained in both rhetoric and philosophy. He studied rhetoric in Athens under the Christian Prohaeresius for five years from the age of fifteen through nineteen starting sometime between 361 and 364 ce, depending on his date of birth.26 After his time in Athens, he returned home to Sardis to study philosophy under Chrysanthius, a man who had also been his grammar teacher before Eunapius left for Athens. He also seems to have received some sort of training in medicine, sufficient to be recognized by the imperial physician, Oribasius, doctor and political advisor to the Emperor Julian (361–363 ce), as an amateur expert on medicine. Oribasius spoke to Eunapius’s expertise in the preface of a handbook on medicine which he dedicated to the rhetor.27 His training in all three of these areas—rhetoric, philosophy, and medicine—accounts for the different intellectual lineages he traces in his Lives, the work in which Sosipatra appears. Although we have similar kinds of collective biography from earlier epochs in the form of Philostratus’s Lives of the Sophists and Diogenes Laertius’s Lives

24. Eunap., VS 6.94–96.

25. Richard Goulet discusses the problems of Eunapian chronology in volume 1 of his critical edition: Eunapius, Vies de philosophes et de sophistes, 5–23. He also gives an overview of what he believes is the likely chronology of Eunapius’s life (24–34). This chronology draws on earlier work by the same author: Richard Goulet, “Sur la chronologie de la vie et des oeuvres d’Eunape de Sardes,” Journal of Hellenic Studies 100 (1980): 60–72. Some of Goulet’s conclusions have been challenged by other scholars. See, for instance, Thomas M. Banchich, “On Goulet’s Chronology of Eunapius’ Life and Works,” Journal of Hellenic Studies 107 (1987): 164–67; Thomas M. Banchich, “The Date of Eunapius’ Vitae Sophistarum,” Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 25, no. 2 (2004): 183–92.

26. Thomas M. Banchich, “Eunapius in Athens,” Phoenix 50, no. 3/4 (1996): 304–11.

27. Philip J. Van Der Eijk, “Principles and Practices of Compilation and Abbreviation in the Medical ‘Encyclopaedias’ of Late Antiquity,” in Condensing Texts—Condensed Texts, ed. Marietta Horster and Christiane Reitz (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2010), 525.

of Eminent Philosophers, Eunapius’s Lives is a strange collection at first glance and requires explanation, especially if we are to understand the place of Sosipatra in the larger narrative.

To account for the impetus for writing collective intellectual biography in Roman antiquity, we have to understand the competitive nature of rhetoric, philosophy, and medicine in this period. These biographical works were one form of collective self-fashioning and a strategy for creating group identity through the careful, deliberate, but selective “recording of relationships,” both personal and textual.28 Schools, especially of philosophy in major centers such as Athens and Alexandria, but also smaller centers such as Ephesus, Pergamum, Antioch, and Sardis, were highly competitive with each other for students.29 And they functioned as proxy families both while students attended and after they departed to start careers. We will discuss the nature of late ancient philosophical education in much greater detail in later chapters. But suffice it to say that teachers were often thought of as parental figures and fellow students as siblings.

Eunapius’s participation in three educational lineages serves as the framework for the way in which he records the genealogical connections he emphasizes in the fourth-century intellectual landscape. It is important to understand, however, that a different biographer may well have traced other connections and recorded the teaching activities of very different groups, many of which are now substantially lost to us because they were not tended to in writing by a figure such as Eunapius. Rather, their stories were likely transmitted only via oral testimony, which was the more likely form of transmission in antiquity.30 For our purposes, it is Eunapius’s participation in one of the Platonic communities of ancient Asia Minor and Lydia that is most important, a community whose lineage he works to trace back to Plotinus and his student Porphyry. It is a lineage that Eunapius most closely identifies with one of Porphyry’s students in particular, namely, Iamblichus of Chalcis, who

28. Kendra Eshleman, The Social World of Intellectuals in the Roman Empire: Sophists, Philosophers, and Christians, Greek Culture in the Roman World; Variation: Greek Culture in the Roman World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 149–76.

29. Edward Jay Watts, “The Student Self in Late Antiquity,” in Religion and the Self in Antiquity, ed. David Brakke, Michale L. Satlow, and Steven Weitzman (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005), 236–41.

30. Edward Jay Watts, “Orality and Communal Identity in Eunapius’ Lives of the Sophists and Philosophers,” Byzantion 75 (2005): 334–61.

was instrumental in introducing a ritual focus to his particular school of Platonist philosophy.

This ritually focused Platonism is most often referred to as “theurgy” or “god work.” The term first appears in a work called the Chaldean Oracles, a work written by two legendary men named Julian, a father and son.31 This work consists of “theological, cosmological, and theurgically practical information presented in dactylic-hexameter verse.”32 I will discuss this particular tradition of philosophy in more detail in subsequent chapters. For now, it is important to understand that after Plotinus and his emphasis on philosophy as a path for both returning to the divine source of all creation and the divinization of the soul itself by purifying it of its engagement with the material world, some of his Platonist successors began to question what role traditional rituals such as prayer, sacrifice, statue making and animating (i.e., inviting a god to inhabit his or her image), and divination and/or prophecy played in this process. Philosophers such as Porphyry and Iamblichus, despite disagreeing vehemently about animal sacrifice, believed that at least some of these rituals, all of which were associated with traditional forms of polytheistic worship, aided in these processes of purification and divinization precisely because they were divinely instituted practices.33 In other words, they were given to humans to aid them in their efforts to maintain relationships and connections with higher beings in the cosmos and even in helping humans become more akin to these superior

31. There is a very rich literature on the Chaldean Oracles. Some of the most important works include Polymnia Athanassiadi, “The Chaldaean Oracles: Theology and Theurgy,” in Pagan Monotheism in Late Antiquity, ed. Polymnia Athanassiadi and Michael Frede (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999), 149–84; Sarah Iles Johnston, Hekate Soteira: A Study of Hekate’s Role in the Chaldean Oracles and Related Literature, American Classical Studies 21 (Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1990); Ruth Majercik, “Chaldean Triads in Neoplatonic Exegesis: Some Reconsiderations,” Classical Quarterly 51, no. 1 (2001): 265–96; Ruth Majercik, The Chaldean Oracles: Text, Translation, and Commentary (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1989).

32. Johnston, Hekate Soteira, 2.

33. A number of works address the theurgical focus of Porphyry and Iamblichus as well as the debate between them over whether blood sacrifices were necessary for the salvation of the soul. See in particular Elizabeth DePalma Digeser, A Threat to Public Piety: Christians, Platonists, and the Great Persecution (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012); Aaron Johnson, Religion and Identity in Porphyry of Tyre (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013); Heidi Marx-Wolf, “High Priests of the Highest God: Third-Century Platonists as Ritual Experts,” Journal of Early Christian Studies 18, no. 4 (December 22, 2010): 481–513; Heidi Marx-Wolf, Spiritual Taxonomies and Ritual Authority: Platonists, Priests, and Gnostics in the Third Century c.e. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 13–37. The most thorough scholarly account of Iamblichus’s understanding of theurgy is Gregory Shaw, Theurgy and the Soul: The Neoplatonism of Iamblichus (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995).

spirits. As such, these rituals worked with the inherent connections built into the ancient cosmos by the highest god, his demiurgic creator, and all the lesser co-creative divinities, namely, gods, daemons, heroes, and so forth. Furthermore, each of these lower divinities was tasked with ordering and administering the cosmos.

At the core of this worldview was the idea of an interconnected cosmos, where levels were symbolically and ontologically linked in hierarchical ways. This worldview can be summed up in the notion of cosmic sympathy, which “is based on the idea that certain chains of noetic ‘Forms’ and symbols emanate from the gods through subsequent ontological grades of reality, permeating every strand of the cosmos, including the physical world.”34 In this context, a symbol is “a direct efficacious and ineffable link with divine truth, operating on the level of a talisman.”35 In other words, these symbols were built into the fabric of the cosmos from the very beginning precisely to help lower beings connect with higher ones and higher ones to assist lower ones. The theurgist, the ritually adept philosopher, was able to harness the power of these symbols and various kinds of rituals for the benefit of his or her own soul and those of others for a range of purposes, some more noble than others.36 Eunapius’s accounts of many philosophers in the Plotinian-Iamblichan lineage include vignettes that involve such ritual engagement. This is certainly the case for his narrative of Sosipatra’s life. This leads us to consider where she fits in to his collective biography.

Sosipatra’s Place in the Lives

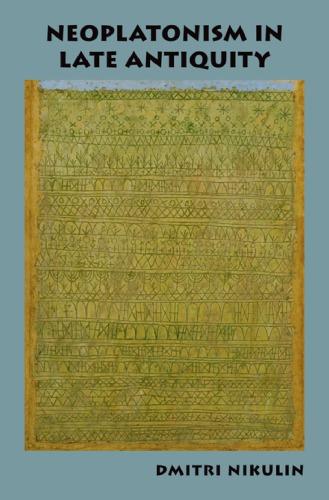

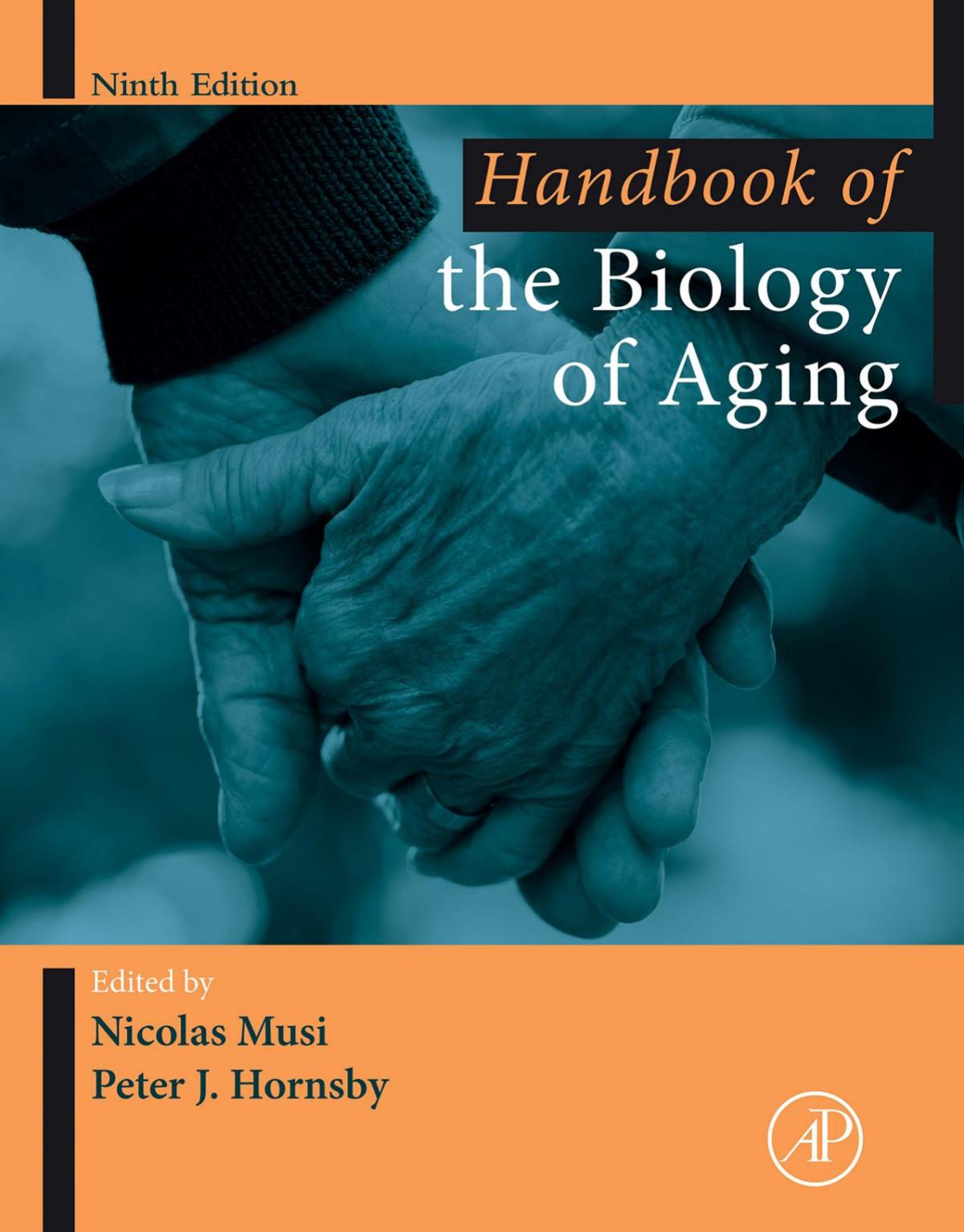

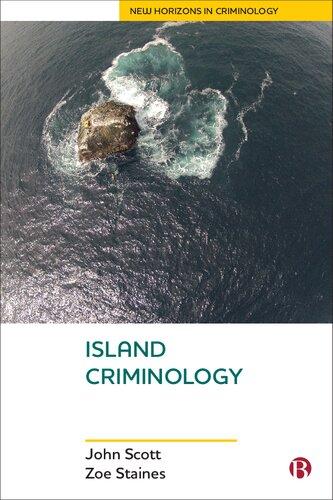

It is clear that Eunapius saw Sosipatra as a crucial member of the Iamblichan lineage he was both tracing and constructing (see Figure 1.2. This is because she may have been a teacher to his beloved Chrysanthius, who was in Eunapius’s mind a clear successor to the school of Iamblichus via Chrysanthius’s other teacher Aedesius, one of Iamblichus’s most important students. But Sosipatra had another connection to this lineage, via her husband Eustathius, who was also a student of Iamblichus but one who did not pursue a career in teaching philosophy. He chose a life

34. Crystal Addey, Divination and Theurgy in Neoplatonism: Oracles of the Gods, Ashgate Studies in Philosophy and Theology in Late Antiquity (Burlington, VT: Routledge, 2014), 25–26.

35. Addey, Divination and Theurgy, 26.

36. Addey, Divination and Theurgy, 26.

Ammonius Saccas

Anatolius

Porphry

Iamblichus

LonginusOrigen

Sopater 2 Chaldeans

Aedesius

Eustathius

Antoninus & 2 Brothers

Chrysanthius

Plotinus Eunapius

Eusebius

Sosipatra

Maximus Emperor Julian

Figure 1.2. Succession of Philosophers, adapted from Richard Goulet, Eunape de Sardes, Vie de philosophes et sophists, Tome I (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2014), 136.

of diplomacy, politics, and civil service instead. This was a path that a number of Iamblichus’s students followed.37 To move back a generation, Iamblichus taught Sopater, Theodorus, Euphrasius, Eustathius, and Aedesius, the last of whom took over the school and taught Chrysanthius. It is also likely that he was taught by Sosipatra when she and Aedesius shared students in Pergamum after the death of her husband.

37. Both Brown and Athanassiadi make arguments that late ancient philosophers were important public figures often playing important roles at court, as ambassadors, and even at times as outspoken critics of imperial policy: Athanassiadi, “The Divine Man of Late Hellenism”; Peter Brown, “The Philosopher and Society in Late Antiquity,” in The Philosopher and Society in Late Antiquity: Protocol of the Thirty-Fourth Colloquy, 3 December 1978, ed. Edward C. Hobbs and Wilhelm Wuellner (Berkeley, CA: Center for Hermeneutical Studies in Hellenistic and Modern Culture, 1980), 1–17.

Sosipatra of Pergamum

These genealogical links are one way of thinking about how Sosipatra fits into the narrative. They explain her presence in the collective biography in the simplest and least illuminating terms. She is there because she taught Eunapius’s teacher and the student of Iamblichus’s successor. But the question of her place in the Lives is a far more complicated one when we consider that she herself does not participate in this pedagogical lineage as a student, as well as if we ask what role or roles she plays in the narrative. Eunapius seems to be making a number of points by focusing his attention on Sosipatra. In addition to situating himself and establishing his intellectual pedigree in relation to three professional domains—philosophy, rhetoric, and iatrosophistry (i.e., learned/theoretical medicine or medical education as opposed to everyday practical medicine)—Eunapius is engaged in reflecting on and constructing an ideal of intellectual life for traditional Greco-Romans in the dynamic and often hostile sociocultural and religious landscape of the late fourth century ce. This was a time when the Roman Empire was becoming increasingly Christianized, and career paths within the Christian church were attracting larger numbers of talented elite intellectuals with training similar to that of Eunapius, pulling them away from traditional vocational paths at court, in schools, and in juristic settings. In this context, Eunapius appears to be making a number of key points with his overall narrative. He argues for a moderate form of Platonic theurgy that avoids some of the more extreme practices that could be construed as not merely harnessing but coercing cosmic forces, practices that some contemporaries would have classified as “magical.” Sosipatra plays a critical role in making this point in the Lives. At every juncture of her story, she is open and receptive to the influence and inspiration of divinity, a mere instrument in the demiurgic project of ordering and informing the cosmos, work that is the purview of higher spirits and divine humans. At the same time, she is never seen engaging in more “aggressive” forms of ritual activity such as statue animation or casting or countering spells. As we will see, her approach to ritual and philosophical activity is most clearly juxtaposed with that of Maximus of Ephesus, who turns out to be a very ambivalent figure in the Eunapian account. Sosipatra is not the only figure Eunapius utilizes to reflect the ideal philosophical way of life, but she plays a critical role in exemplifying the kind of philosophical life that would best allow for the continued existence of Iamblichan Platonism in a Christianized world where the more problematic aspects of theurgy are downplayed

or effaced in favor of an approach that maintains a clear understanding of cosmic hierarchy, despite subscribing to the idea that humans can participate in divinity in a number of ways.

The second role that Sosipatra plays in the text, I argue, is she acts as a point of critical contrast to the Christian ideal of the virginal or celibate female ascetic who is free from the taint of non-scriptural education, who does not marry or bear and raise children, and who participates in forms of self-deprivation at times so severe she compromises her health even to the point of death. Sosipatra, on the other hand, acts like a proper elite woman. She marries, bears three children, and arranges for the management of her estate through the agency of her family friend, Aedesius. There is not a whiff of the ascetic about her. In some respects, it should come as little surprise that Eunapius includes such a detailed and laudatory portrait of a holy woman such as Sosipatra, given that his Christian counterparts, that is, hagiographers, were engaged so enthusiastically in producing celebratory biographies of female martyrs and saints in large numbers—stories of women from the same class as Sosipatra roughly speaking, such as Macrina and Melania the Elder and Younger.38 But Christians were also producing portraits of reformed prostitutes, actresses, and “nymphomaniacs” such as Mary of Egypt or Pelagia.39 Some hagiographies also focused on cross-dressing saints such as Thecla, as well as on saints whose bodily mortifications led to the severe compromise of their physical health.40 These include accounts of women such as Syncletica, a late ancient monastic woman who allowed her jaw bone to fester to such a degree that it was finally given a funeral while still intact, presumably as a paramedical measure

38. There is a rich literature on these female Christian figures. For an introduction to some of these figures, see Ross Shepard Kraemer and Mary Rose D’Angelo, eds., Women and Christian Origins (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999). For studies of individual figures, see, for instance, Elizabeth Clark, The Life of Melania the Younger: Introduction, Translation, and Commentary (New York: Edwin Mellon Press, 1984); see also Elizabeth Clark’s forthcoming book in this series on Macrina.

39. For further reading on “holy harlots” as they are sometimes called, see Virginia Burrus, the Sex Lives of the Saints: An Erotics of Ancient Hagiography (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004); Patricia Cox Miller, “Is there a Harlot in This Text? Hagiography and the Grotesque,” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 33, no. 3 (2003): 419–35; Benedicta Ward, Harlots of the Desert: A Study of Repentance in Early Monastic Sources (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1978).

40. For an introduction to the figure of Thecla, see Jeremy W. Barrier, The Acts of Paul and Thecla: A Critical Introduction and Commentary (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2009). For a study of her popularity in Late Antiquity see, Stephen J. Davis, The Cult of St. Thecla: A Tradition of Women’s Piety in Late Antiquity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001). For cross-dressing saints, see Kristi Upson-Saia, “Gender and Narrative Performance in Early Christian Cross-Dressing Saints’ Lives,” Studia Patristica 45 (2010): 43–48.

to stop the spread of necrosis.41 Eunapius presents a counter-portrait in his biographical sketch of Sosipatra to what would have seemed like extreme and disruptive experiments in gender construction for many traditional Greco-Roman polytheists.

My approach to the question of what roles Eunapius asks Sosipatra to play in his narrative draws on insights from a number of feminist historiographers such as Judith Butler, Elizabeth Clark, Amy Richlin, and Joan Scott.42 In addition to presenting what I hope will be a rich contextualization of the rather sparse details Eunapius offers us about his heroine such that readers will learn something about the life of elite intellectual women in the late fourth century ce Roman East, I also advance the argument that Sosipatra frequently “vanishes” from the text as a real historical woman and is replaced by these two “Sosipatra functions,” to use Clark’s term, namely, her function as a critic of both overly zealous theurgists and overly enthusiastic Christian female ascetics.43 The exploration of these “Sosipatra functions” will happen primarily in the final chapter of the book in the context of a discussion of our subject as an oracle, diviner, and theurge. The other chapters trace her story chronologically from childhood through to the time when, as a widow or as a separated woman, she led her own philosophy school in Pergamum.

41. Pseudo-Athanasius, Vita Syncletica 111 (PG 28, 1556).

42. Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, Thinking Gender (New York: Routledge, 1990); Elizabeth A. Clark, “The Lady Vanishes: Dilemmas of a Feminist Historian after the ‘Linguistic Turn,’” Church History 67, no. 1 (1998): 1–31; Amy Richlin, Arguments with Silence: Writing History of Roman Women (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2014); Joan W. Scott, “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis,” American Historical Review 91, no. 5 (1986): 1053–75.

43. Clark, “The Lady Vanishes,” 28.