Introduction

The Armenian Question

Probably Armenia was known to the American school child in 1919 only a little less than England. The association of Mount Ararat and Noah, the staunch Christians who were massacred periodically by the Mohammedan Turks, and the Sunday School collections over fifty years for alleviating their miseries—all cumulate to impress the name Armenia on the front of the American mind.

—Herbert Hoover, The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover: Years of Adventure (1951)

The Armenians and their tribulations were well known throughout England and the United States. This field of interest was lighted by the lamps of religion, philanthropy and politics. Atrocities perpetrated upon Armenians stirred the ire of simple and chivalrous men and women spread widely about the English-speaking world. Now was the moment when at last the Armenians would receive justice and the right to live in peace in their national home. Their persecutors and tyrants had been laid low by war or revolution. The greatest nations in the hour of their victory were their friends, and would see them righted.

—Winston Churchill, The World Crisis: The Aftermath (1929)

The First World War was the foundational crisis of the twentieth century. It was the “calamity from which all other calamities sprang,” as historian Fritz Stern put it.1 The conflict precipitated the collapse of international order, prompting the downfall of empires and provoking the displacement of entire populations. The world had never before witnessed death and destruction on this scale. Almost ten million combatants were killed and millions more were permanently disabled. Yet even among this carnage, Theodore Roosevelt was adamant that one atrocity was unique in its horror. The former president would declare unequivocally in 1918 that “the Armenian massacre was the greatest crime of the war.”2 On the other side of the Atlantic, Lord Robert Cecil, the British undersecretary for foreign affairs, went even further, stating, “without the least fear of exaggeration, that no more horrible crime has been committed in the history of the world.”3

Roosevelt and Cecil encapsulated the attitude of their fellow countrymen to the wartime annihilation of around one million Armenian Christians in the Ottoman Empire.4 Indeed, the plight of the Ottoman Armenians had long been a humanitarian cause célèbre in the United States and across the British Empire, since earlier massacres of over 100,000 Armenians by the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid’s forces and Kurdish irregulars between 1894 and 1896. The Armenians’ staunch Christian faith, their distinctive national culture, and their position as downtrodden subjects of an Islamic Empire that many Americans and Britons considered despotic gave them a unique hold on the public imagination in both countries. This appeal was strengthened by the Armenian claim to be descended from Noah, whose ark, according to the Book of Genesis, came to rest on Mount Ararat—in the heart of the Armenian homeland. American affinity for the Armenians was further bolstered by the preponderant influence of their Protestant missionaries in the Armenian provinces of the Ottoman Empire. Yet prior to the 1894–1896 massacres, the US government had largely avoided any political entanglement in the so-called Armenian question—the diplomatic term for the issues that arose from the insecurity of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire—retaining its traditional policy of aloofness from events in the Near East and Europe more generally. As American power grew at the turn of the twentieth century, however, so did the sense of responsibility felt by leading Americans for preventing the kind of atrocities to which the Armenians had fallen victim.

In 1896, the US Congress adopted an unprecedented resolution that called for US diplomatic intervention on behalf of the Armenians to “stay the hand of fanaticism and lawless violence” in the Ottoman Empire.5 This marked a major turning point in the nation’s international humanitarianism and signaled a fundamental departure in American foreign policy. Throughout the nineteenth century, private charities and churches had taken the lead in marshaling relief efforts for humanitarian catastrophes around the world, while the federal government declined to involve itself diplomatically in any such crises occurring outside its traditional sphere of interest in the Western hemisphere. In its response to the Armenian massacres, however, the US government was drawn for the first time toward outlining a political solution to a humanitarian problem occurring elsewhere.6 Legislative agitation did not ultimately lead to executive action in 1896, but it did reveal a bold new spirit in US diplomacy that grew stronger over time. This spirit was evident when the United States intervened militarily to address a humanitarian problem closer to home in 1898, that of Spanish oppression in Cuba, establishing a Pacific and Caribbean empire in its wake. It was also discernible in US diplomatic interventions under President Theodore Roosevelt on behalf of Eastern European Jews and in the Congo during the opening decade of the twentieth century. John Quincy Adams’s famous warning that Americans should not go overseas “in search of monsters to destroy,” a dictum that shaped

the nation’s foreign policy for much of the nineteenth century, no longer appeared to deter American activism.7

When renewed massacres broke out in the Ottoman Empire in 1904, however, Roosevelt recognized that the country lacked the instruments and inclination to engage in a large-scale military intervention to protect the Armenians, despite widespread public sympathy. Nor were most Americans prepared to maintain a consistent engagement in global affairs after Roosevelt left office; the Armenian question was left to Britain and the other European powers to try and resolve. Only with the upheaval and turmoil of the First World War did the potential for US intervention on behalf of the Armenians emerge as a realistic possibility. In the shadow of the unprecedented wartime destruction of the Armenian people, Americans initiated an unparalleled relief effort to save the survivors. But for some Americans, impassioned expressions of private philanthropy were insufficient. Out of office, Roosevelt led calls for the US government to use its power to protect the Armenians, but the official response under his rival President Woodrow Wilson was initially characterized by restraint. No official protest was made when the wartime massacres began in 1915 and despite declaring war on Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1917, the first deployment of US power in Europe, the country remained at peace with the other great Central Power, the Ottoman Empire, for the duration of the conflict. Yet Wilson’s apparent inaction in the face of the massacres belies the outsized role that the Armenian question would come to play in his own vision of reforming global politics. At the end of the war, Wilson hoped Americans would take the lead in establishing a new world order, guaranteeing “justice to all peoples and nationalities, and their right to live on equal terms of liberty and safety with one another, whether they be strong or weak.”8 And in this new order the United States would have a special role to play in Armenia. In addition to urging US membership in the new League of Nations he had outlined, Wilson hoped that it would accept a mandate for the nascent Armenian state. The mandate would not only resolve the Armenian question, therefore, but also secure and symbolize the United States’ new global role.

This work traces the story of the US response to the Armenian question as an essential but neglected window onto the rise of the United States to world power. It sets the United States’ Armenian diplomacy within the broader context of a public debate in American society and politics over the nature and purpose of the nation’s newly established power at the turn of the twentieth century. In doing so, it explores the controversy over the role of humanitarian intervention in US foreign policy during this period. More broadly, it examines the significant impact that the Armenian question exerted on American ideas about international order and explains why this question came to assume such importance to so many Americans, particularly Roosevelt and Wilson.

In order to fully understand the American response to the Armenian question, it is necessary to consider it in tandem with the British response. American and British policies on this issue offer a critical, yet overlooked, perspective on the evolution of Anglo-American relations in this period, and particularly Britain’s response to the rise of the United States to world power at a time when its leaders were worried about their own nation’s international position. Growing US involvement in international politics at the turn of the twentieth century encouraged British dreams of an Anglo-American alliance, and this book shows how Britain’s statesmen attempted to use shared sympathy for the Armenians to help advance that goal. It also explores why a number of prominent American advocates of intervention for the Armenians, most notably Roosevelt, were determined supporters of the United States assuming a leading international role in partnership with Britain. Furthermore, it explains why an American mandate for an independent Armenia, through the League, emerged as a central tenet of Britain’s strategy for the postwar world. Woodrow Wilson and British Prime Minister David Lloyd George both came to see American protection of the Armenians as key to the establishment of a reformed international system. However, they had very different visions of the new international organization, and an appreciation of their respective policies on the question of an American mandate for Armenia illuminates the thinking behind their peace plans after the First World War.

The unprecedented scale and destruction of the war and its aftermath would instigate a revolution in the conduct of international relations and inspire new thinking about global political reform. Ideas about restructuring the world order proliferated in many societies but were particularly pronounced in the United States and across the British Empire.9 While France, the other principal victorious power, was primarily concerned with the threat posed by its German neighbor, the relative distances of Britain and the United States from the European continent afforded them different degrees of latitude in addressing the problems presented by the war.10 Furthermore, the two powers had greater capacities to shape world affairs than other countries, and this enabled its policymakers to pursue a wider range of options. There was a fundamental disparity, though, between the global positions and strategic outlooks of the two nations. An awareness of this is crucial to understanding their positions on the Armenian question specifically and on the postwar international order more generally.

By the end of the First World War, American economic strength was on a vastly different scale than Britain’s. This economic dominance combined with the pivotal US role in the Allied victory meant the world was now forced to come to terms with “America’s new centrality” in the international system.11

Unlike Britain and France, the great power status of the United States was less dependent on its acquisition of overseas possessions. The geostrategic foundation of its position in the world remained its dominance of the Western hemisphere, which helps explain why the nation’s initial enthusiasm for establishing a colonial empire after the 1898 war with Spain rapidly abated. On the other hand, Britain possessed a worldwide empire and its interests were tied up in its imperial system. This made it more vulnerable to the geopolitical and economic consequences wrought by the war. Britain’s victory in the conflict came at a huge financial cost and, coupled with the breakdown of the prewar global order, in which Britain was the leading power, this meant that its capacity to exercise a hegemonic role in the postwar international system was increasingly constrained.12 As a result, a number of British policymakers looked to a cooperative relationship with the United States as the basis for a postwar order, after its intervention in the war on the Allied side had fueled dreams of an AngloAmerican combination.13

The League of Nations was envisaged as the mechanism to convert the wartime Anglo-American association into a postwar partnership.14 More specifically, it was the League’s mandate system that was seen by British statesmen as the means to achieve this goal. This initiative was designed to allow the allied nations, under “mandate” from the League, to assume responsibility for administering the former German colonies and new states that had emerged after the wartime collapse of the Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, and Russian empires. American acceptance of a protectorate over one of these territories was central to British visions for the new organization, ensuring that the United States became an active player in international politics outside its traditional sphere of influence, and helping to forge the Anglo-American alliance that was so important to many British policymakers. This idea of an Anglo-American “colonial alliance,” as one of its leading proponents, British Colonial Secretary Lord Milner referred to it, is one of the most intriguing of the forgotten ideals of the World War I period.15 What has not been fully appreciated by historians is the significance of the United States assuming a mandate in order to cement that partnership or the importance of the Near East as the crucible where that new order would be forged, after Wilson agreed to accept mandates, subject to Congressional assent, for Armenia and the Ottoman capital Constantinople. Wilson’s commitment to assuming a mandate came not from his desire to establish an Anglo-American colonial alliance, however, but from his determination for the United States to play a hands-on role in establishing a different form of world order. For Wilson, the mandates were a manifestation of this new order, providing an American alternative to Europe’s imperial practices and, more importantly, ensuring that the United States assumed a position of global leadership. Which mandates the United States would assume and the struggle over them are crucial to

understanding British and American strategies for an international organization and their competing conceptions of global order. Furthermore, the controversy over the mandates would serve as the culmination of more than two decades of debate in the United States and Britain over whether—and, if so, how—to resolve the Armenian question.

That period witnessed such enormous global upheaval that the Armenian issue is often little more than a footnote in most accounts of US foreign affairs or Anglo-American relations.16 Conversely, there are a number of excellent, more focused studies that explore the American and British responses separately across this period or, in the case of Britain, within the context of imperial politics and with regard to wider European geopolitics.17 But considering the American response alongside the British shows the connections between them, and reveals something broader about the historic debates over the United States’ growing power, its evolving relationship with Britain, and the development of ideas on humanitarian intervention and global order at the turn of the twentieth century.

This book charts how the idea of an American solution to the Armenian question evolved from the mid-1890s, when the plight of the Armenians first imprinted itself on the American consciousness just as the United States began its rise to world power.18 It explores why the 1894–1896 massacres led to the emergence of a public and political discourse on America’s responsibility to aid the survivors and punish the perpetrators, and how US government officials grappled with the legal and geopolitical implications of intervention in the Armenian question. It examines the intersection between US activism on behalf of the Armenians and its intervention over Cuba in 1898, as well as the complex interplay between humanitarianism and empire in the nation’s conception of its “civilizing” role in international affairs at this time. It also uncovers how these initial Armenian atrocities led to the first serious discussion of a joint AngloAmerican intervention in the Near East and the first proposal for an American protectorate over the Ottoman Empire, one that would safeguard the Armenians and ultimately stimulate a regional, and potentially global, entente between the two powers. It explores Roosevelt’s thinking on an alliance with Britain, a significant but neglected feature of which was a shared responsibility to censure humanitarian atrocities that offended the civilization of the age, and the protection of peoples such as the Armenians. It traces the genesis of Roosevelt’s doctrine of American responsibility to intervene in response to “crimes against civilization,” a set of principles that was profoundly shaped by the 1894–1896 massacre of Ottoman Armenians, along with the actions that he took in support of this.19 And it explains why, by the end of Roosevelt’s presidency, he had come to regard American missionaries as the best chance of achieving a long-term solution to the Armenian question. It sketches out this “missionary solution” by

exploring the missionaries’ informal “civilizing mission” in the Ottoman Empire, their developing relationship with US government officials and business leaders, and the ties they forged with their international peers, particularly in the British Empire, as they sought to build support for a campaign to transform the Near East.20

After this ambition was brought to a catastrophic halt when the Armenians were threatened with wholesale destruction amidst the turmoil of World War I, American missionary leaders, despite pioneering a vast relief effort that “quite literally kept a nation alive,” insisted that the United States refrain from declaring war on the Ottomans.21 In uncovering the motivations behind missionary policy, this book also explores Woodrow Wilson’s pragmatic decision not to declare war on the Ottoman Empire after US entry into the conflict in 1917 and sheds light on the US relationship with its wartime partners, of whom Wilson insisted the United States was an “associate” rather than an “ally.” The Armenian question grew in significance in Wilson’s own mind once he was freed from the constraints of war and set to establish a reformed international system, in which the Ottoman Empire would be dismembered and the security of its subject peoples guaranteed.22 This study reveals why Wilson believed his new global order, led by the United States and centered on the League of Nations, was the only permanent way of protecting peoples such as the Armenians and maintaining world peace. In explaining why the Armenians were the only people for whom Wilson specifically asked Americans to assume a mandate, it shows how their independence struggle, more directly than that of any other people during the League fight, forced Americans to confront the extent of global responsibilities that they were willing to assume.23 Based on research in the papers of the Armenian National Delegation, the Ottoman Armenians’ representatives to the cabinets of the great powers, it divulges how the Armenians themselves and the diaspora community in the United States, which numbered just 100,000 by the time of the First World War, sought to appeal to Americans to safeguard their security and for help in determining their future. Furthermore, it analyses how leading British statesmen attempted to entice the United States into assuming a mandate and helping to construct a system of international governance, built around Anglo-American collaboration and based on shared political responsibilities in the Near East.

The book concludes by discussing why the question of an Armenian mandate, although generally overlooked in studies of the League fight, is so significant to understanding American attitudes to this organization. It explores the findings of the two investigative groups that Wilson sent to the Near East—the King-Crane and Harbord Commissions—to assess conditions in the region and ascertain whether the United States should accept a mandate. It explains why the debate in the US Senate over a mandate ultimately reached its conclusion in

June 1920, more than two months after the defeat of the Versailles Treaty. And it highlights how the lingering American mistrust of British imperialism, as well as the growing British disillusionment with American indecision over whether to commit to a new role in the Near East, profoundly impacted the postwar relationship between the two countries with significant consequences for regional and global order.

As Herbert Hoover and Winston Churchill recalled, the fate of the Armenians was of special concern to the peoples of the English-speaking world at the outset of the twentieth century. The aim of this book is to show why the survival of one of the world’s smallest nations became so entangled with the foreign policies of the two most powerful states, the relations between them, and their search for a new global order.

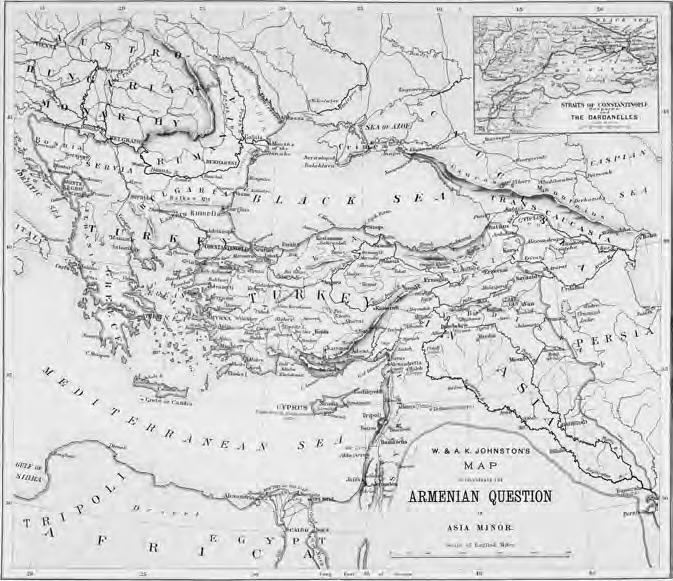

While a century ago many Americans and Britons were aware of the rough contours of Armenian history and their position in the Ottoman Empire, most contemporary readers are unlikely to be so familiar with the issue. To understand the larger story, therefore, requires setting it against the historical backdrop of the Armenian question itself and its place within the larger Eastern question. Prior to falling under Ottoman rule, the Armenians had developed a distinctive national culture. Around the sixth century b.c. they had emerged as an identifiable people, occupying lands between the Black, Caspian, and Mediterranean seas. In a.d. 301, twelve years before Constantine’s Edict of Toleration legalized Christian worship in the Roman Empire, the Armenians became the first people to embrace Christianity as their state religion and they held resolutely to their faith over the succeeding centuries.24 By 1400, however, most of the territory that had historically belonged to them, in what is today referred to as Eastern Anatolia and Transcaucasia, had fallen under Ottoman control, with a separate Eastern section occupied by Persia. In the Ottoman Empire, the Armenians were members of a multiconfessional and multiethnic polity but, as an Orthodox Christian minority, they were considered second-class citizens and forced to pay special taxes. Nevertheless, while the Empire thrived, most Armenians lived peacefully in their historic homeland, working as tenant farmers for feudal Muslim landlords. A significant number prospered in international commerce or entered the skilled professions. However, by the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the Empire was in decline and the Armenians’ position had deteriorated. The Empire’s administrative, economic, and military infrastructure was beset by internal corruption and it was increasingly difficult to compete with its dynamic European rivals. The Armenians labored under the weight of growing official discrimination and their tax burden became more oppressive as the Empire’s finances came under greater strain.25

As the Ottoman state struggled to adapt to the challenges of the nineteenth century, many of its subject minorities, influenced by romanticist ideologies that were spreading from Europe, underwent a cultural and political revival. A number of these groups successfully fought for political independence, occasionally supported by particular European states, causing the Ottomans to lose most of their Balkan provinces. As the Empire contracted, the European powers grew increasingly concerned. Sprawled over an area of pivotal strategic significance, the Empire lay at the crossroads of three continents, a critical component in the European balance of power. Its decline threatened to destabilize the continent and gave rise to the Eastern question in European diplomacy, of what should be done about the moribund Empire. At the same time, Ottoman liberal elites, painfully aware of the Empire’s precarious condition, enacted the Tanzimat edicts of 1839 and 1856 in an attempt to establish a modernized, centralized state and stave off the prospect of military and economic decline. This extensive series of reforms failed to convince the European powers that the condition of the “Sick man of Europe” was improving.26 While eager to capture any territorial spoils, they were equally determined that none of their rivals should profit if the Empire collapsed. Following the Crimean War, they pledged to maintain the Empire’s territorial integrity. Yet this did not prevent them from seeking to advance their geopolitical and commercial objectives in Ottoman territories. Nor were they averse to exploiting the growing nationalist ambitions of the Empire’s minority peoples for their own ends.27

During the early to mid-nineteenth century, Britain emerged as the Ottoman Empire’s principal supporter among the European powers. This had less to do with any great affinity for the Ottomans and was more a reflection of the British government’s concerns about Russia, particularly the threat that Russian expansion posed to Britain’s lines of communication to its imperial possessions in the East. In particular, British leaders were determined to prevent Russia from seizing control of the Ottoman capital, Constantinople, which was situated on the Dardanelles Straits, the strategic nexus that linked Europe and Asia. If Russia occupied Constantinople then its fleet would have access to the Mediterranean Sea and could cut British links to its territories in Asia, while denying Britain’s navy access to the Black Sea, where it could threaten Russia’s own coastline. As a result, successive British governments supported the Ottoman Empire as a buffer against Russia. Lord Palmerston, who dominated British foreign policy for much of the period from 1830 to 1865, was a key figure in devising this strategy. While in office as both prime minister and foreign secretary, he worked to develop closer ties with Constantinople despite criticism from opponents, who condemned the Ottomans for their corruption and treatment of Christian minorities. In particular, Palmerston and his successors were determined to keep Russia from exploiting its claim to be the defender of Ottoman Christians to

justify any intervention in the Empire. As a result, Britain’s diplomats in the Near East acted to deter hopes among the Empire’s minority populations that they would receive British support for any separatist aspirations.

As the Armenians had spread throughout the Empire and no longer comprised a majority in their historic territories, they were initially less susceptible than other communities to visions of national independence. Nevertheless, Armenians also experienced a cultural revival in the nineteenth century. Thousands enrolled in schools run by European and American missionaries, while hundreds traveled to Europe for higher education. They subsequently established schools and newspapers for their conationals across the Empire. Gradually there built up a network of literate Armenians imbued with a sense of national self-consciousness. This cultural awakening was accompanied by Armenian disillusionment with the effects of the Tanzimat reforms. Furthermore, Armenians were increasingly concerned about their economic and physical security, which was threatened by corrupt government officials and growing lawlessness in the eastern provinces of Anatolia, where most still resided. The Armenians’ desire to ensure the security of their communities and property, within an increasingly unstable and illiberal Empire, led to the emergence of the Armenian question as part of the larger Eastern question.28

Between 1875 and 1878 multiple insurrections erupted in the Ottoman Empire, in what came to be known as the Great Eastern Crisis. In 1876, the outbreak of a rebellion in Bulgaria was brutally repressed by the Ottomans and resulted in an international outcry. Britain’s Liberal leader William Gladstone, then in opposition, denounced the “Bulgarian Horrors” and condemned Benjamin Disraeli’s Conservative government for its support of the Ottomans. In doing so, he captured the mood of the outraged British electorate. While recognizing that Britain’s public had turned viscerally anti-Ottoman, Disraeli continued to favor them, supporting the new young sultan, Abdul Hamid II, who took the throne in 1876 and granted the Empire’s first constitution that year. Disraeli’s major fear was that Russia, convinced that Britain would be prevented by public opinion from opposing a Russian intervention, intended to exploit the Bulgarian atrocities to expand its own territory. In 1877, Russia did invoke its position as the guardian of the Empire’s Orthodox Christians to declare war on the Ottomans. After advancing deep into Ottoman territory, the Russian forces pressured the defeated Ottomans into signing the Treaty of San Stefano in March 1878, which diminished Ottoman possessions in Europe still further.29 Moreover, this treaty, and the Berlin Treaty that revised it later that year, signaled the internationalization of the Armenian question.

The Russians, who in 1829 had annexed the eastern provinces of historic Armenia, occupied most of Ottoman Armenia at the end of the 1877–8 conflict. Ottoman Armenian leaders appealed to victorious Russian commanders for the

peace terms to make provisions for their protection. Consequently, the Russians inserted a clause in the Treaty of San Stefano, making withdrawal of their troops contingent on the Ottomans introducing reforms in the territories and ensuring the Armenians were protected from marauding bands of Kurds and Circassians, their principal tormenters. However, Britain and Austria-Hungary were alarmed that San Stefano’s terms allowed Russia to expand its influence toward the Mediterranean and called a Congress in Berlin to revise the treaty. In particular, Disraeli regarded Russian domination of the area from the Caucasus to Eastern Anatolia, where the historic Armenian homeland was situated, as a critical threat to the British passage to India. In Berlin, Disraeli worked to limit Russian territorial gains in Eastern Anatolia.30 To the disappointment of the Armenians, the Berlin Treaty stipulated that Russian forces should immediately withdraw from Eastern Anatolia. Although the Treaty instructed Constantinople to carry out reforms in the Empire’s Armenian provinces and “to guarantee their security,” under the supervision of the European Powers, the nature of that oversight was left undefined and no mechanism was provided for its enforcement.31 The Cyprus Convention of 1878, under which the Ottomans accepted Britain’s occupation and administration of Cyprus as a base for preventing Russian seizure of Ottoman territory, also provided imprecise instructions to the sultan to implement reforms in the Armenian populated regions of the Empire. The Armenians were nonetheless hopeful that the Treaty and the presence of British troops in Cyprus would enable the European powers to intervene on their behalf and protect them from repression by imperial authorities. The presence of Western officials and missionaries within their communities only heightened these expectations. The Great Powers initially cooperated to pressure the Ottomans to fulfill their treaty obligations but soon became distracted by imperial interests elsewhere, and the issue of Armenian reforms slipped down the diplomatic agenda.

The Russo-Turkish War led to the Ottoman Empire losing one-third of its territory and 20 percent of its inhabitants.32 It also exposed the Empire’s precarious economic position and led to the establishment of the Ottoman Public Debt Administration, under which Britain and France took control over Ottoman fiscal policy, further undermining Constantinople’s sovereignty. Armenian appeals to the Europeans for intervention were another source of humiliation for the tottering Empire, and raised the specter of a potential enemy within. In this context, the Sultan placed a greater emphasis on Islamic solidarity to reinforce his fragile regime, in the process helping to inculcate anti-Christian sentiment and a sense of their subordinate status in the Empire. He was committed to securing the loyalty of Kurdish tribes in Eastern Anatolia and using his fellow Muslims to maintain regional order. Consequently, the Kurds were allowed, and often encouraged by local Ottoman authorities, to terrorize Armenian villages. Now

convinced the Ottoman government was tyrannical and complicit in their oppression, and despairing of outside aid from the powers, growing numbers of Armenians began organizing in self-defense groups. Inspired by the struggles of Balkan Christians, many believed that they needed to take up arms to protect themselves. In addition, several secret political societies had been established by the 1890s. Unlike their Balkan counterparts, however, most of these organizations were not yet prepared to champion national independence. Instead they emphasized regional autonomy, cultural freedoms, civil liberties, greater economic opportunity, and the right to bear arms.33 In 1894, members of one of these political groups, the socialist Hunchak Party, organized local farmers in the village of Sasun to resist attempts by local Kurdish tribal chiefs to collect feudal dues in exchange for vows of protection. In the resulting confrontation several Kurds were killed. Determined to check any suggestion of revolution, Sultan Abdul Hamid’s forces descended on Sasun and the surrounding villages. The ensuing destruction led to the deaths of at least 3,000 Armenians, provoked outrage across Europe and North America, and ensured the Armenian question was once more a live issue in international diplomacy.

There was widespread support for the Armenians in Britain, where prominent liberals, led by former Prime Minister Gladstone, had continued to rail against the condition of Eastern Christians in the Ottoman Empire. Furthermore, hostility to the Ottomans now cut across party lines and the Armenian massacres ensured that anti- Ottoman feeling became entrenched even among Conservatives.34 The Sasun massacre encouraged Lord Rosebery’s Liberal government to pressure France and Russia to revive the issue of Armenian reform. In May 1895, the three powers issued a joint proposal to the Ottoman government that recommended consolidating the six Anatolian provinces with the largest Armenian populations into a single administrative unit, the release of political prisoners, reparations for the people of Sasun and surrounding villages, and the establishment of a permanent commission to ensure reforms were implemented. As the sultan procrastinated, 4,000 Armenians, led by the Hunchaks, marched in protest in Constantinople and were again met with violence. Alarmed at the prospect of a mass Armenian insurrection in Anatolia, and concerned that Armenian revolutionists were already colluding with Macedonian insurgents in the western provinces of the Empire, Ottoman authorities unleashed a campaign of terror in a bid to maintain the status quo. Government troops and regional notables incited mob violence across Eastern Anatolia, while Kurdish militias were given free rein to attack Armenian communities. By the end of 1896, systematic pogroms had claimed the lives of between 100,000 and 200,000 Armenians, in a series of atrocities that came to be known as the Hamidian massacres.35

The brutality of this crackdown would inspire renewed debate in Europe over a nation’s responsibility to intervene on behalf of a persecuted people. While there was a long history of European states intervening in each other’s internal affairs for a combination of strategic reasons, the protection of coreligionists and the advancement of political liberties, by the beginning of the nineteenth century the practice of nonintervention in the domestic politics of another sovereign state had been largely established as a norm in European diplomacy.36 However, this principle did not fully extend to the Ottoman Empire, which the European powers did not believe was “civilized” enough to be immune from outside intervention, and which they were increasingly convinced could not or would not reform itself. Under the special status that the Eastern question occupied in European politics, the powers gave themselves permission to intervene if large-scale disturbances occurred, for instance if the Ottoman authorities violently suppressed a revolt and massacres resulted.

While European diplomats debated what criteria—such as the number of people massacred and the nature of the killing—needed to be met to provoke action, the principal determinant for sanctioning an intervention was whether it enhanced or endangered European peace. As a result, the interventions that did occur in the nineteenth century were largely carried out in concert, such as when Britain, France, and Russia joined together to intervene in Greece in 1827 or when France secured permission from the other powers to occupy parts of Greater Syria in 1860 after the massacre of thousands of Maronite Christians. In these cases the intervening states were hardly motivated by pure humanitarian concerns, with each acting to secure clear, discernable interests, but they were, for the most part, careful to assure the other European powers that their military actions were not primarily intended for their own economic or territorial self-aggrandizement. As such, these were practical, if imperfect, examples of “humanitarian intervention”, a term that entered the international diplomatic vocabulary during the 19th century, though its contours remained imprecisely defined and its validity intensely debated by contemporary legal theorists.37 These interventions were often precipitated by pressure from an outraged public opinion, particularly in powers with parliamentary systems of government and a relatively free press like Britain and France. By the late nineteenth century, eyewitness reports of atrocities from foreign correspondents and accounts from missionaries were relayed at previously inconceivable speed thanks to the recently invented telegraph, arousing indignation and demands for action.38 Undoubtedly, certain victims attracted a far greater degree of support for action than others. The campaigns for intervention in the Ottoman Empire were predominantly directed at protecting Ottoman Christians (and occasionally Jews), while violence against Muslims, notably in Crete or against the Druze

in Lebanon, was largely ignored. However, as Davide Rodogno, a leading scholar of these interventions, has argued, although “selective and biased” they can still be termed “humanitarian” when their principal motive was to “save strangers from massacre.” Nevertheless, the fact that they were aimed at the Ottoman Empire, chiefly on behalf of Christians, reflected an inclination to contrast Europe’s “civilization with that of a ‘barbarous,’ ‘uncivilized’ target state, prone to inhumanity, incapable of reforming itself and whose sovereignty and authority they contested.”39 Consequently, interventions were intended initially to save fellow Christians, subsequently to spread European ideas of civilization to the Ottoman Empire and, most importantly, were only undertaken after evaluating the consequences for continental order.

The Hamidian massacres occurred on a larger scale than previous bloodshed that had prompted outside intervention and provoked widespread public outrage and denunciation of Ottoman “barbarity” across Europe. The bipartisan support for the Armenians in Britain, encouraged the Conservative Lord Salisbury, who replaced Rosebery as prime minister in June 1895, to seek support from the other European powers in order to coerce the sultan into bringing an end to the massacres. However, by the mid-1890s, the configuration of European geopolitics had shifted. No power was willing to risk continental stability, or their own interests, to intervene on behalf of the Armenians and, to Salisbury’s exasperation, the only collective action that the European powers could agree upon was an ineffectual naval demonstration in 1895.

Unlike the European powers, the United States had no substantial material or geostrategic interests at stake in the issues surrounding the massacres. Its government had traditionally avoided involvement in the diplomatic disputes arising out of the Eastern question, regarding it as an extension of European affairs and therefore an inappropriate sphere for political involvement. The United States was not a signatory to the Berlin Treaty and therefore did not share with the European powers the responsibility for overseeing the Armenian reforms. In addition, its regional economic interests were minimal. Yet the United States did have a significant longstanding link to the Ottoman Empire that ensured public and governmental interest in Near Eastern affairs. American missionaries had been proselytizing in the Empire since the beginning of the nineteenth century and had established the most wide-ranging mission field of any nationality group, with Armenians as their principal wards. Within American society, their expertise was unparalleled and they proved instrumental in shaping public perceptions of the Empire and its inhabitants. Missionaries represented the most active American involvement in the Near East during an era of limited political engagement.40 As American power expanded in the last decade of the nineteenth century, however, and turmoil in the Ottoman Empire deepened,

missionary leaders would urge their government to adopt a more assertive regional role, protecting not only them and their institutions but the Armenians too. The ensuing debate over the appropriate response to the Armenian atrocities would encourage many leading Americans to question the continued relevance of their most revered diplomatic shibboleths and to contemplate a new world role.