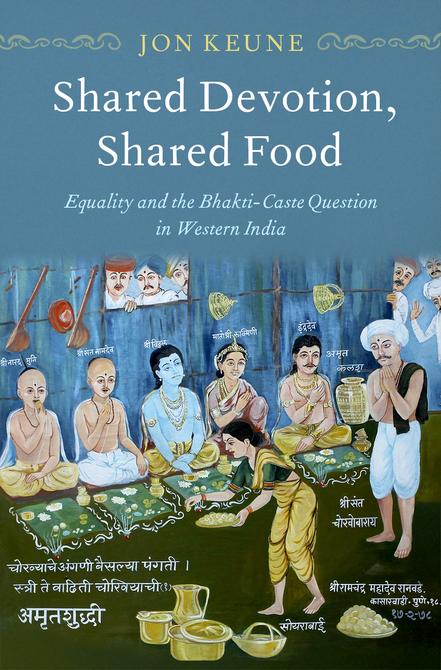

Shared Devotion, Shared Food

Equality and the Bhakti-Caste Question in Western India

JON KEUNE

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021933132

ISBN 978–0–19–757483–6

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197574836.001.0001

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Integrated Books International, United States of America

5.

Eknāth (1903)—V. R. Śirvaḷ

Kharā Brāmhaṇ (1933)—K. S. Thackeray

(1935)—Prabhāt Film Company

Toci Dev (1965)—G. G. Śirgopīkar

Mahārāj (2004)

Acknowledgments

Although this book originated in my dissertation research, its present shape is the result of much gestation and growth after the dissertation was finished. During the initial research and in the years since then, I have benefited from the help, guidance, and inspiration of more people than I can count. This is a good argument for writing a book more quickly—to finish it before the author can forget any of his debts.

I cannot overstate my gratitude to Jack Hawley, who guided me through my doctoral studies and has been a supportive and provocative conversation partner ever since. His steady encouragement and feedback on ideas created a stable ground on which I found my scholarly footing. The trouble with drawing inspiration from such a prolific scholar as Jack, however, is that it becomes difficult to recognize when I may be repeating something that he already wrote or said somewhere. I am sure that a systematic reading of all Jack’s publications would reveal similarities to my own arguments beyond the ones that I have explicitly recognized. I hope this will be viewed sympathetically, as a sign of the deep intellectual impression that a teacher leaves on a student.

Many others have helped along the way, especially Rachel McDermott, Chun-fang Yü, Anupama Rao, Udi Halperin, Patton Burchett, Anand Venkatkrishnan, Joel Bordeaux, Katherine Kasdorf, Joel Lee, Christian Novetzke, and Anna Seastrand, all of whom I had the privilege of learning from, since we first met at Columbia University. Anne Feldhaus has provided inspiration and wise counsel, both in India and the United States. The Centre for Modern Indian Studies at the University of Göttingen was an inspiring place to spend two years, especially due to the friendship and intellectual vibrancy of Michaela Dimmers, Sebastian Schwecke, Stefan Tetzlaff, Rupa Viswanath, and Nathaniel Roberts, among others. At the University of Houston, Lois Zamora, Anjali Khanojia, and Keith McNeal were excellent conversation partners. I am grateful to Martin Fuchs for our conversations and for his very thought-provoking conferences in Erfurt over the years. In India, I have benefitted immensely from the expertise of more people than I can possibly thank here. These include especially V. L. Manjul, Sujata

Mahajan, Sucheta Paranjpe, Satish Badwe, Meera Kosambi, Shantanu Kher, Y. M. Pathan, Vidyut Bhagwat, and Narsimha Kadam. Yogiraj Maharaj Gosavi and his family in Paiṭhaṇ were very generous with their time and patience, allowing me to accompany them on pilgrimage and learn about their famous ancestor Eknāth and his legacy. R. S. Inamdar and B. S. Inamdar kindly introduced me to their family heritage and the background of a lesser-known text about Eknāth. Shashikala and Rajani Shirgopikar generously shared their fascinating experiences in the traveling theater troupe that is described in Chapter 6. The staffs at the Eknāth Saṃśodhan Mandir in Aurangabad and the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute in Pune provided much support in using their respective archives. Many others allowed me into their lives and made me feel at home in India, especially Wasim Maner and Tahir Maner and their respective families, as well as Maxine Berntsen, Michihiro Ogawa, Samrat Shirvalkar and Kalyani Jha, Smita Pendharkar, and Subhash and Sumitra Shah. Two of my guiding lights when I started learning about India in college, Eleanor Zelliot and Anantanand Rambachan, profoundly shaped my perspectives on and especially my relationships to Hinduism and India in ways that have endured and are even evident in this book.

My colleagues in the Religious Studies Department and the Asian Studies Center have made my time at Michigan State University (MSU) very collegial and fulfilling. Arthur Versluis and Siddharth Chandra have been especially supportive over these years, intellectually and administratively. I have treasured feedback from students, especially Anneli Schlacht, who spotted many ways to make the book more readable. Mahesh and Trupti Wasnik, members of the Ambedkar Association of North America, as well as Salil Sapre at MSU, have been very helpful and inspiring conversation partners. Enduring friendships and invigorating scholarly collaborations have been a source of endless inspiration, especially with Gil Ben-Herut and the Regional Bhakti Scholars Network, and with Max Rondolino and the Comparative Hagiology group.

My research and travel have been generously supported by grants from the American Institute of Indian Studies, the Dolores Zohrab Liebmann Fund, and the Fulbright-DDRA program, as well as from Columbia University, the University of Göttingen, the University of Houston, and MSU. This book would not have been possible without them and their sources of funding, including American and German taxpayers. I also appreciate the Schoff Publication Fund at the University Seminars at Columbia University for their

help in publication. Material in this work was presented to the University Seminar: South Asia.

Oxford University Press has been very helpful in bringing this book to print, especially through the strange and difficult logistics brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. Two anonymous reviewers gave tremendously valuable feedback on an earlier draft. Cynthia Read, Drew Anderla, and Zara Cannon-Mohammed have been a pleasure to work. Sarah C. Smith of Arbuckle Editorial and Do Mi Stauber provided crucial support in proofreading and indexing.

My families in Wisconsin and Taiwan have provided unwavering support and understanding through all the stages of this book. I am especially thankful to Tzulun for her patience and encouragement along the way. Although our intercontinental navigations added some challenges to the writing, these pale in comparison to all the joy, love, and wonder that have grown out of our journeying together.

From early on, my parents showed me the community-building power of a table that was always open and welcoming to anyone. It was not until writing this book that I realized how much of an impact that had on me and so many others who joined us for meals over the years. My mother has been a constant source of support and sagely advice about life (and cooking!). Words cannot express my gratitude. I especially want to remember my father, who passed away shortly before this book was finished. He offered crucial assistance in, among so many other things, building the treadmill writing desk at which I spent countless hours and miles. It stands—quite sturdily—as an example of how material objects move and sustain us, even in intellectual work. I dedicate this book to his memory and hope that it would have made him proud.

Abbreviations

Marathi

BhV Bhaktavijay

EC Eknāthcaritra

PC Pratiṣṭhāncaritra

ŚKĀ Śrīkhaṇḍyākhyān

SSG Sakalasantagāthā

Sanskrit

BhG Bhagavad Gītā

BhL Bhaktalīlāmṛt

BhP Bhāgavata Purāṇa

BU

Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad

ChU Chāndogya Upaniṣad

MBh Mahābhārata

TU Taittirīya Upaniṣad

Introduction

This book centers on a question: can the idea that people are equal before God inspire them to treat each other as equals? Can theological egalitarianism lead to social equality? Looking around the world today and in the past, there are many reasons to be skeptical or to say that what might be possible in theory has been realized rarely, if ever, in practice. Nonetheless, the appeal of equality does not go away. To the contrary, equality as an ideal has become almost a universal, objective standard by which cultures and religions should be measured, in many people’s minds.1 A religious leader who announces that their tradition teaches inequality among its adherents based on gender, race, ethnicity, or other factors would seem out of sync with the times. Such a tradition would be regarded as anti-modern, even threatening to the functioning of liberal democracies. Taking for granted this benchmark of modernity, as if it were the obvious developmental goal of societies, historians have sought to uncover how equality developed in the past. They have often identified religious doctrines and practices as being seeds of social equality.

On a recent trip to Japan, I joined some local colleagues for dinner at the Kofukuji Buddhist temple in Nagasaki’s Chinatown. The chef for this meal was the temple’s head priest, who said that he was following recipes that a Chinese monk in his lineage had carried to Japan several centuries ago.2 The priest welcomed us into his home, seated us on tatami mats around a low table, and served us tea. Then, he placed in our hands a sheet of paper with information about the meal to come. Part of the description read, “The Fucha style of cuisine means to have tea and a meal together at a round table without recognizing social statuses of gathering guests so as to create a friendly atmosphere.” Along with fond memories of the dinner and the camaraderie around the table, this sentence about ignoring social distinctions while eating stayed with me.

As someone who is used to studying South Asia, I hesitate to comment on what prompted this statement in a Japanese temple, whether five hundred years ago or when someone sat at their computer more recently, typing up that information sheet in English. But what is most interesting about this

Shared Devotion, Shared Food. Jon Keune, Oxford University Press. © Oxford University Press 2021.

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197574836.003.0001

claim is not its historicity but the sheer fact that it appeared at all, especially in a land whose society was notoriously rigid in medieval times. Experiencing this Buddhist meal in Nagasaki reinforced two hunches that had prompted me to write this book: modern people often try to identify seeds of social equality in premodern religious traditions, and food is often central in demonstrating that equality in practice.

In this book, I focus on a case of apparent egalitarianism, food sharing, and religion in India. At the core is a deceptively simple question about India’s regional Hindu devotional or bhakti traditions, which have included in their ranks people who were routinely marginalized from most other Hindu traditions—women, low-caste people, and Dalits (so-called “Untouchables”). The question is this: did bhakti traditions promote social equality? Or more elaborately, when bhakti poets taught that God welcomes all people’s devotion, did this inspire followers to combat social inequalities based on caste? This question hovers around many stories about bhakti saints, such as the following one.

On the śrāddha day [a ritual to commemorate the ancestors] Eknāth behaved without distinction to everyone. Whoever thinks this way likewise satisfies others. He announced a meal to the community of brahmans. The food preparations began. Before the brahmans arrived, Dalits (cāṇḍālas) brought and set down bundles of wood for the kitchen. . . . Excellent raw rice, uncooked rice, and cooked rice were strained in the kitchen. At that time, a strong fragrance spread. All the Dalits experienced it. . . . Eknāth saw them directly, and he prostrated himself before them. The Dalit men and women remained standing with hands joined respectfully. Doing prostration from afar, they said “Please give us food. We Dalits are low and miserable. What savory food that is! If spice is available, then there is no salt—such is our food [i.e., something is always lacking]. Only in our dreams could we even hear of such savory food. We do not know it first-hand, Eknāth. This desire has come to us; please fulfill it. . . . If you think to trick us, then remember your oath to your guru Janārdana.” Eknāth said, “Janārdana is in all beings. The Enjoyer is one. To imagine division is foolish.” Eknath then fed the Dalits in his house. After they had eaten, he made a request: “The brahmans should not hear of this.” He begged all the people to hold the secret in their bellies. Family and good friends everywhere agreed and kept the news hidden. They did not let it be known. Meanwhile, at the river, the brahmans did their bath, sandhyā, ritual offerings, and god-worship. Then

a Dalit woman (mātangīṇī) came to the Gangā [Godāvarī] riverbank, carrying food with her. The Dalit woman sat near the brahmans. She had received the food from Eknāth. The brahmans reviled her, calling out “Hey, cāṇḍāḷiṇī!” and demanding that she leave. She said to the brahmans, “Ekobā [Eknāth] served us. Becoming the ancestors, we went to his house. He made us all satisfied. You should go for food. The cooking is finished. I will eat my food peacefully, here on the bank of the Gangā. Today we are Eknāth’s ancestors. Why are you intimidating me? I just thought to have food on the bank of the Gangā, so I came.” Hearing her words, the brahmans were shocked. “Eknāth, such a sage, has acted completely against prescribed behavior. To hell with his knowledge. No rice-balls [essential to the ritual] should be offered by us. There was no feeding of brahmans. He fed Dalit people.” . . . One said, “There should be punishment.” Another said, “His head should be shaved. Cut and throw away his sacred thread.” One said, “Catch and beat him. A complete punishment must be given.” One said, “Beating isn’t necessary. Pull out his topknot and put it in his hands.” One said, “Make him do purification rituals. Otherwise, his preparations will be destroyed. Nothing should be done in vain.” . . . [Eknāth dispatched his servant, himself a brahman, to invite the brahmans to the śrāddha. Incensed at Eknāth’s effrontery, the brahmans gave Eknāth’s servant a beating. Later, the brahmans approached Eknāth’s house and found, to their amazement, that after they had refused to partake of Eknāth’s meal, the deceased ancestors were seated inside, eating.] They stood for a moment and watched the marvel. Whoever came to the meal recognized their own ancestors. The brahmans were stunned. They tried to speak, but no words came to them. The ancestors’ meal concluded. . . . Eknāth put out the plates of leftovers at the end of it all, saying, “Our ancestors came here and certainly ate joyfully.” Eknāth himself rolled in the leftover plates. The arrogance of the brahmans was destroyed. They stood there silently. Coming outside, Eknāth prostrated himself before the brahmans. “Svāmīs, have mercy here, you should certainly come to eat.” Looking them in the face, Eknāth embraced all the brahmans. They replied, “The ancestors were obviously fed. Your deeds are incomprehensible. Blessed are your deeds. Blessed, blessed is your sincerity. Blessed is your path of devotion. Blessed are you, the one guru-bhakta.”3

Was Eknāth challenging the primacy of caste when he defied ritual precedent and served food to the Dalits instead of brahmans? Why did Eknāth feed the Dalits without hesitation if he was so worried about how the brahmans

would respond? Did the experience inspire the Dalit woman to perceive herself differently and become more assertive with the brahmans at the river? Setting aside questions about the story’s historicity, why did hagiographers in later centuries find it valuable to repeat versions of this story? What exactly does it say about bhakti and caste?

Ambiguous stories about bhakti and caste are hardly limited to brahmans. One vivid example is about the 14th-century Dalit saint Cokhāmeḷā Cokhāmeḷā, an unwavering devotee of the god Viṭṭhal, regularly worshiped him from outside his temple since Dalits were not allowed to enter it. One night, Viṭṭhal honors Cokhāmeḷā by inviting him inside for a conversation. A group of brahmans angrily assemble and ban Cokhāmeḷā from the town. While in exile, Cokhāmeḷā is visited by Viṭṭhal again, who sits down and joins the Dalit saint for a meal. A passing brahman hears Cokhāmeḷā talking to the god, but the brahman cannot see Viṭṭhal. The brahman thinks that Cokhāmeḷā is putting on an insolent theatrical display, so he slaps him across the face. That evening, when the brahman enters Viṭṭhal’s temple, he sees that the god’s stone image has a swollen cheek, exactly where he had slapped Cokhāmeḷā. Realizing his mistake, the brahman apologizes to Cokhāmeḷā and, taking his hand, brings him into the temple to be near Viṭṭhal again. What does this story, with the chastised brahman and vindicated Dalit saint, signify about caste? Did wholehearted devotion to God reshape the way followers treated people, or did such tales remain just entertaining tales, without inspiring listeners to change? Could bhakti have helped people to conceive of something like social equality, in a context when people assumed that caste differences were simply part of the natural order?

Since the late 19th century, some liberal Hindu reformers have asserted that bhakti did indeed have socially transformative power. On a popular level still today, many people are inclined to agree, considering the vast corpus of bhakti literatures across languages and regions that depict saints crossing caste boundaries and condemning arrogant brahmans. As many saintly figures around the world do, bhakti saints often exemplify virtues like courage, selflessness, and patience.4 That Indian school textbooks and children’s literature regularly highlight saints’ ethical behavior to young learners should come as no surprise. It is easy to see why the image of bhakti saints promoting equality continues to resonate.

But dissenters abound as well. One of the most pointed and influential examples was the learned Dalit leader, Bhimrao B. R. Ambedkar, who offered a very clear assessment of the matter:

The saints have never, according to my study, carried on a campaign against Caste and Untouchability. They were not concerned with the struggle between men. They were concerned with the relation between man and God. They did not preach that all men were equal. They preached that all men were equal in the eyes of God—a very different and a very innocuous proposition, which nobody can find difficult to preach or dangerous to believe in.5

Ambedkar wrote this in 1936, in the aftermath of a speech that was deemed too radical to be delivered in person. Organizers of the Jāt-Pat-Toḍak Maṇḍal (Society for Breaking Caste) had invited Ambedkar to deliver a lecture. But when they read an advance copy and realized just how forcefully Ambedkar planned to argue his case, they withdrew the invitation out of fear of violent reprisals. Undeterred, Ambedkar went ahead and published it himself— Annihilation of Caste. The publication quickly caught the attention of M. K. (Mahatma) Gandhi, who mostly agreed with Ambedkar’s critique of untouchability but thought to address the problem in a very different way. In response, Gandhi penned “The Vindication of Caste,” in which he argued that the abusive caste system is a corruption of an earlier, reasonable division of labor. He chided Ambedkar for focusing on negative examples of injustice while ignoring the many bhakti saints and reformers who represented Hinduism in a much better light.6 Ambedkar emphatically denied that he had overlooked this and wrote the passage just excerpted: the saints’ endorsement of spiritual equality did not extend to changing society. In 1935, Ambedkar famously had announced that he would not die a Hindu. Two decades later, after countless more speeches and agitations and after literally writing equality into Articles 14 and 16 of the Indian Constitution, Ambedkar converted to Buddhism and led some 400,000 Dalits with him—a very public rejection of Hindu norms.

Ambedkar’s frank assessment of the bhakti saints is important for this book in many ways. His reference to two separate realms—spiritual and social—is exceptionally clear and effective in laying out the modern configuration of the problem. It issues a major challenge for scholars and proponents of bhakti, to assess soberly how bhakti has changed or not changed people’s social behavior in practice. On the other hand, for many people, taking Ambedkar’s critique of caste and untouchability seriously has meant completely turning away from popular religious traditions like bhakti, to envision a strictly rational and in some sense secular future. Figures like Jñāndev,

Kabīr, and Gandhi also cast shadows on modern understandings, but they do not leave bhakti in the dark in quite the way that Ambedkar’s does. Reckoning Ambedkar’s thought and legacy with bhakti traditions as historical entities and living communities today is a massive undertaking that extends far beyond this book.

Ambedkar’s assessment of bhakti was unambiguously negative, but it is important to keep his context in mind. Ambedkar formulated the bhakticaste question around social equality and then answered the question as he deemed it necessary, based on his experiences of Indian society and his goals for changing it. However, the question’s directness belies a deeper complexity. As he rebutted Gandhi’s criticism, Ambedkar responded to a particular man in a specific context. Ambedkar had other goals than to address all the historiographical nuances of how bhakti related to caste, if he considered them at all. He was not impelled to account for the forces that converged to make the question seem natural to ask in the first place. In the chapters ahead, I unpack assumptions that lie behind modern formulations of the bhakti-caste question and recover premodern ways of construing it that are less apparent to us now. But how can we become acquainted with these other ways of thinking and their possible impact on people’s social behavior? I think it is helpful to pay attention to a substance that vitally connects theory and practice.

Food, as Ambedkar recognized in his writings and experienced often painfully in his life, was a basic tool for regulating caste. Social scientists have long observed food’s essential roles in building and ordering communities around the world. It makes good sense to approach the bhakti-caste question through food and commensality. For it is in matters involving food that we see most clearly and mundanely the clashing values of bhakti’s inclusivity and caste’s hierarchy. Investigating shared food or “critical commensality” is a crucial yet under-studied site where we can see the theory of bhakti meeting the challenge of practice, just as it can help understand other cultures and time periods.7

How should we approach the question, “Did bhakti promote social equality?” A logical start is to analyze the two key terms—bhakti and equality and trace what they meant to people who invoked them in the past. I carry out this spadework in Part I. Ultimately, however, only part of my interest is in modern people’s use of the bhakti-caste question to interpret, appropriate, glorify, or denounce the past. How did people understand the relationship of bhakti and caste before modernity?

As we will see, framing the bhakti-caste question as one of social equality entails using modern concepts to imagine the premodern world. Whenever admirers of bhakti have suggested that it endorsed equality, critical voices quickly pointed out counterexamples in which caste continued to play major roles in bhakti traditions. Indeed, there are many historical examples of authors and traditions preaching devotion to God yet maintaining the social status quo. Even today, some bhakti traditions are explicit about observing caste, especially among their leaders.

The bhakti-caste question has troubled scholars, devotees, and the Indian populace alike, not only because of what it reveals about the past but because of what one’s answer to the question implies for the world today. If bhakti did or at least could overcome caste to realize social equality, then there is a prospect of constructively inheriting something from bhakti traditions to work for social change now. In this perspective, living bhakti traditions have the potential to be agents of social change. But if bhakti did not and cannot promote social equality, this would suggest that bhakti traditions should be abandoned or, at least, that their messages should be relegated to the realm of personal piety or historical curiosity. Viewed in this way, living bhakti traditions would appear weighed down by obsolete and inadequate ideas, making it impossible for even devotees who sincerely desire social change to overcome caste. How we answer the question bears not only on understanding the past but on human relations in the present. This is especially the case for Ambedkar’s followers and lower-caste adherents to bhakti traditions, who often find themselves now competing for limited resources. It is not only an academic issue.

I argue that three factors complicate the question of whether bhakti promoted social equality in premodern times. First, most people who address the bhakti-caste question in modern times pay little heed to processes that formulated the question as it now seems familiar to us. This includes a reliance on modern terms to analyze past societies, unnuanced readings of hagiographic sources, and the casual slippage of equality language from one realm of meaning to another. The very nature of the bhakti-caste question requires a multi-disciplinary approach—involving the study of history, hagiography, anthropology, and media—to reckon with the tangle of issues that converged to make the question appear meaningful now. We will distinguish these disciplinary differences clearly, especially in Part I.

Second, we have the problem that the term “equality” in modern usage occludes what I believe was an important practical logic that guided

premodern authors in their handling of bhakti and caste. Because bhakti traditions thrived more on a popular level than an elite one, that logic often was grounded less in the search of intellectual clarity than in pragmatic concerns.8 The legacy of western liberal discourse about democracy and individual rights—a very strong legacy in modern India—obscures the significance of the premodern terms that we find bhakti authors used. This especially happens when translators now resort to the word “equality” to render those key Indic terms into English. I show that the social impact of these Indic terms and the narratives associated with them related more to inclusion than equality. This practical logic appears with special clarity when we observe how stories about food and commensality transformed as they were retold over centuries—the focus of Part II.

Third, the bhakti-caste question defies a simple answer because in precolonial times, the issue was conceived not so much as a question but as a riddle. Arriving at one unambiguous conclusion was less important than holding the tension in mind, working it over and debating different positions, in the way that so many religious people do when dealing with core enigmatic doctrines. The practical logic employed by bhakti traditions when they repeated stories about bhakti and caste is subtle and has outcomes that are not only or even primarily intellectual. One major feature of this practical logic is authors’ strategic use of ambiguity when they discuss bhakti, caste, and food. Stories about food and transgressive commensality allow us to witness that strategy in action.

I expect that some readers may object at this point and cite stories about saints who took staunch positions that are not at all riddle-like or ambiguous. As I discuss in the final chapter, some individual stories and poems may truly represent such radical stances. However, my argument is more about patterns that developed over time and within broader traditions than it is about specific instances. As I make clear in Chapter 1, historians make a crucial decision whether their narratives will focus on long-term trends or short-term exceptions. Within traditions themselves, the process of narration and performance gradually homogenized individual utterances, reshaping how they were retold and applied. When we observe a single telling of a bhakti narrative, it is not immediately evident how that story came into the form that we encounter. As I discuss in Chapters 5 and 6, precisely these details are essential to know to appreciate just what an individual utterance or story was doing and not only saying. After all, it was to this effect—of a tradition that coalesced over time—that Ambedkar was responding.

Despite Ambedkar’s stark judgment of bhakti, it is by no means the case that his view of the bhakti-caste question reached or convinced everyone. Discussions of bhakti and equality did not subside after Ambedkar. One still finds the trope of egalitarian bhakti appearing in newspaper articles, overviews of Indian history, and in the work of scholars who briefly comment on bhakti before focusing their attention on some other historical or cultural feature. Advocates for social change, whether they belong to a bhakti tradition or not, occasionally still hearken to elements of bhakti traditions in efforts to mobilize people, especially in rural areas.9 As we will see in Chapters 3 and 7, the idea that bhakti traditions possess something that, if activated properly, still could spark social change is certainly not dead. A similar sentiment appears among liberal religious advocates around the world, who argue that the spirits of their traditions support the struggle for human rights and social equality. The idea of human rights itself is entangled with religion in many ways.10 Yet it is obvious, at the end of the second decade of the 21st century, that the success of these liberal religious efforts has been spotty at best. So what might that tell us about religion and equality? I think the bhakti-caste question and its relation to food offers a window through which we can perceive some possibilities.

Plan of this book

As I have mentioned, this book proceeds in two parts. In Part I, I trace how the bhakti-caste question in relation to social equality developed in western and Marathi scholarship over the last two centuries. The application of the word “equality” to society and religion is peculiarly modern, and when it took hold in Marathi discourse in the late 19th century, equality was mapped onto several premodern concepts in bhakti literature. In Part II, I recover some of those concepts and show how they functioned before they were displaced by “equality.” In doing so, I consider how one tradition, the Vārkarī sampradāy, followed a practical logic to promote a socially inclusive message. This practical logic is most apparent if we zoom in on examples that span premodern and modern times. Stories of food and transgressive commensality, especially stories about the brahman saint-poet Eknāth interacting with Dalits, do just that. Food’s capacity to symbolize many things makes it an ideal site for debating bhakti’s implications about caste differences. As I trace the changes that food stories underwent in repetitions across various

media from 1700 onward, I highlight how the bhakti-caste relationship went from being a strategically ambiguous riddle to a question that expected—and received—answers.

Although this book centers on the bhakti-caste question in Maharashtra, it deals with modern perspectives on religion that reach far beyond India. Chapter 1 examines these broader issues, especially the common modern narrative that religious traditions routinely failed to bring about social equality. I focus on social historians, whose interest in non-elite people grew out of Marxist sensitivities that, in the course of explanation, predisposed them to view religion as a symptom of distress or instrument of social control but not as a force for social change. I then trace equality’s emergence as an important term in western political and social writing and how modern nation-state rhetoric from the late 18th century onward made it normative. It becomes clear that modern democracies too have often failed to bring about social equality. This enables me to offer a critical take on scholarship about equality in historical religions around the world, and thereby to frame the historiographical issues that occupy the rest of the book.

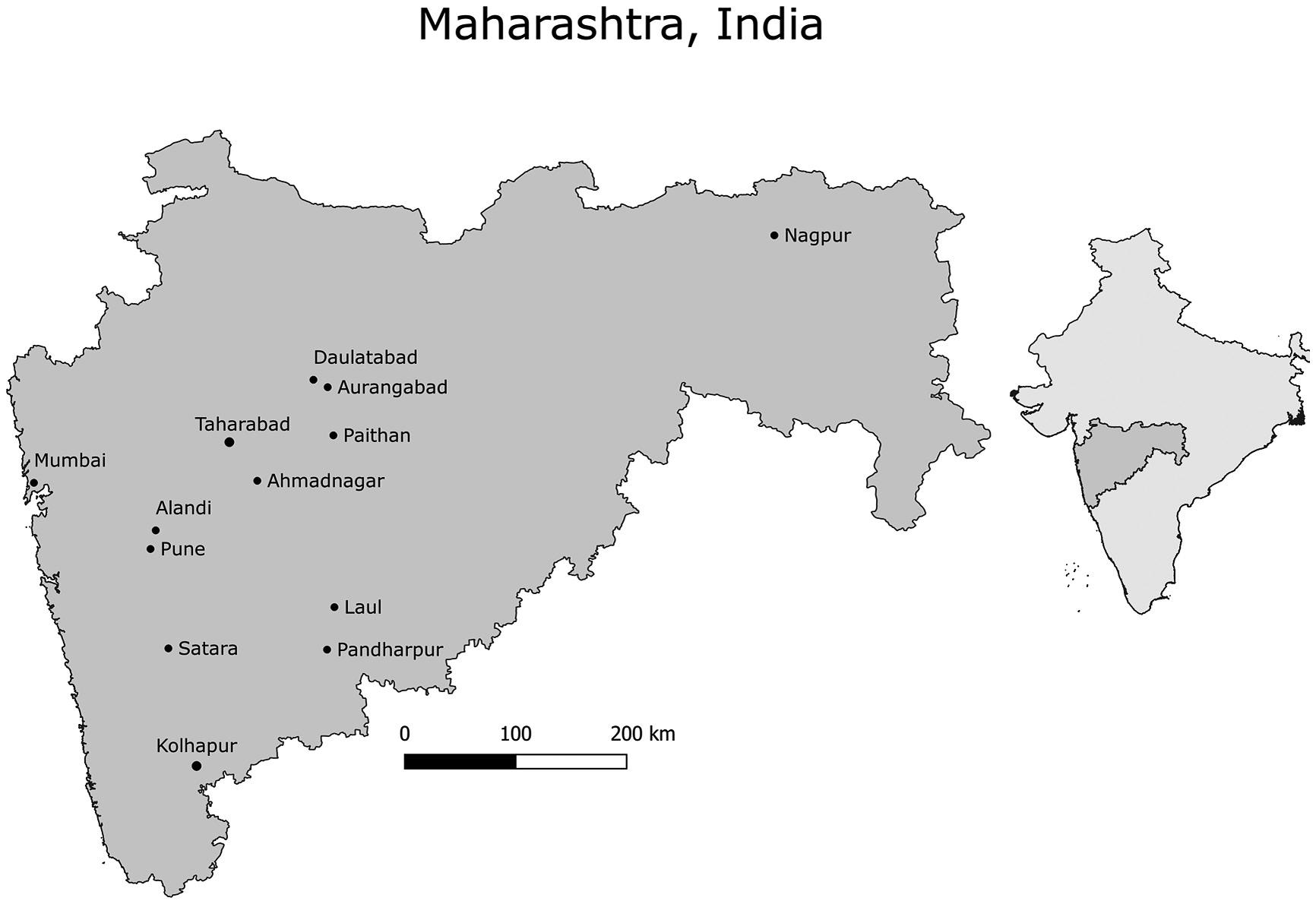

In Chapter 2, I discuss the regional variations of bhakti traditions and the ways in which this diversity complicates theorizing about bhakti in general. Attempts at providing a general overview take one or another (usually North Indian) regional tradition for granted as representative, thereby magnifying the importance of issues and problems which that tradition held as important. As a result, scholarship on bhakti has tended to overemphasize aspects of some traditions while neglecting others. I make clear that my perspective is based in the Marathi-speaking territory of western India (roughly speaking, Maharashtra) where issues of caste and untouchability featured prominently in the region’s traditions. It is probably no coincidence that Maharashtra was home to some of India’s most organized and vocal movements of Dalit assertion in the 20th century. Chapter 2 thus offers an unconventional overview of bhakti scholarship as perceived from western India, where bhakti’s social contribution in terms of democracy, inclusion, and equality was of special interest.

Chapter 3 charts the establishment of equality language in colonial and postcolonial Marathi publications about Vārkarī literature and traditions, and it recovers earlier Vārkarī ways of envisioning the relationship between bhakti and caste. Liberal and some nationalist authors between roughly 1854 and 1930 mined sectarian literatures and stories to construct a non-sectarian

sense of regional identity. This held special importance because of how vital Marathi literary history has been for imagining the region’s social history. More critical views were voiced by low-caste authors and secular rationalists in the late 19th century, and later by Marxist historians. Food featured prominently in pivotal events in many of these proponents’ and critics’ lives. Having described the formation of modern discourse around bhakti and equality, I then begin to recover the precolonial devotional and nondualist Marathi terms that equality language later displaced.

Whereas Part I explores the modern formulation of the bhakti-caste question, Part II examines premodern views as they appear and changed in various renditions of stories about transgressive commensality. In Chapter 4, I show why food features so often in Marathi stories to illustrate problems of social cohesion and division: food functions this way in many cultures and time periods. I highlight interdisciplinary insights from anthropologists and historians about food, especially R. S. Khare and his work on food’s semantic density. I then survey food references in various genres of Hindu literature before homing in on meanings of food in bhakti hagiographies—especially ucchiṣṭa or polluted leftover food.

Chapters 5 and 6 drill down even further, focusing on two food stories whose retellings changed across various media in the precolonial, colonial, and postcolonial periods. At the center of both stories are the brahman saint Eknāth and Dalits with whom he interacts. In the śrāddha story that we encountered earlier, Eknāth serves to Dalits a ritual meal that was intended for brahmans, and his unorthodox action is vindicated miraculously in the face of outraged brahmans. In the double vision story, antagonistic brahmans witness Eknāth in two places at once: simultaneously eating a meal at a Dalit couple’s home and sitting in his own home. Chapter 5 traces renditions of these two stories in Marathi texts between 1700 and 1800. If we approach hagiographical stories with sensitivity to how they change over time, a story about the story is revealed. In this Marathi case, part of that meta-story is that hagiographers strategically employed ambiguity to avoid answering the bhakti-caste question conclusively.

Chapter 6 follows the two stories into the 20th century, as they were represented in plays and films. Three main factors reshaped how the stories appeared on Marathi stage and screen: the narratological demands within and across media formats, equality language that had taken hold in 19thcentury Marathi discourse, and the changing landscape of caste politics in the 20th century, especially with the rise of non-brahman movements. In this