ALAMANNITHURINGIANS

KINGDOM OF TH E FRANKS KINGDOM OF TH E BURGUNDIANS

T H E G O T H I C

KINGDOM OF THE V ANDALS AND ALANS

G A E T U L I A

The eastern Roman Empire and the western Successor States C. 525 Map 1

EAST ROMAN EMPIRE

ATLANTIC OCEAN

KINGDOM OF THE VISIGOTHS KINGDOM OF THE SUEVI

Cordova

KINGDOM OF THE FRANKS

PREFECTURE OF ITALY

PREFECTURE OF AFRICA

MAURETANIANS MOORS

Byzantine Empire at beginning of Justinian’s Reign (527 CE)

Justinian’s conquests

PREFECTURE OF ILLYRICUM

PREFECTURE OF THE EAST

NEWPERSIAN EMPIRE

Map 2

The Conquests of Justinian

Holy Apostles

Holy Apostles Hagia Irene

St. Polyeuktos

St. Euphemia

SS. Sergius and Bacchus Hagia Sophia

Constantinople in the Age of Justinian

Note: Not all buildings and other features were extant at the same time

Churches / Monasteries (mod. Turkish names in italic)

Underground / Open air cisterns

Roads and forums (course & dimensions often approximate)

Map 3

Constantinople in the Age of Justinian

Approx. region boundaries and numbers (Notitia urbis Constantinopolitanae, ca 425 AD)

City quarter / neighbourhoods

Walls (attested / approximate course)

Modern shoreline

The Conquests of Italy

Map 4

The Conquests and Subjugation of Africa

Map 5

Halys

Tarsus Antioch

Apamea

Berytus (Beirut) Damascus

Darial pass

LAZICA

Phasis

Mediterranea n Sea )( )(

Derbent

Black Se a Caspian Sea

Petra

Theodosiopolis

PERSARMENIA

Martyropolis Satala Pharangium Bolum Amida

Edessa Dara Nisibis

SYRIA EUPHRATESIA

Callinicum

IBERIANS LAKHMIDS

Euphrates Orontes

ARABIA

Kura

Baghdad Ctesiphon Sura Beroea Seleuceia Singara Sergiopolis

P ALESTINE

GHASSANIDS

Map 6

The Eastern Front: Justinian and Afterwards

The Gates of Alexander 0 km 250 0 miles 250

Frontier line under Justinian Territories ceded to the Emperor Maurice Chosroes' campaign route in 540

Introduction

Justinian and the Fall of the Roman East

In the mid-sixth century, the imperial authorities in Constantinople began construction of a brand-new city atop a small plateau between two small rivers in the central Balkans: the Svinjarica to the west and the Caricina to the east. The north-western extremity of the plateau was occupied by an acropolis, surrounded by massive ramparts made irregular by the terrain and studded with five huge towers and just the one gate (Figure I.1). Within, a huge episcopal complex (basilica, baptistery, and audience hall) faced an equally ornate seat of secular authority across a colonnaded square. Lower down, another set of walls marked off the five hectares of the upper town. Here were more churches, arcaded streets, and a substantial granary, together with several rich residences and some of the paraphernalia of water management usual to the more arid parts of the ancient Mediterranean, including a cistern and water tower. Outside, a lower town occupied three more hectares, where excavations have thrown up still more churches, another huge water tank, and two massive bath blocks. No economic, administrative, religious, or strategic necessity generated this extraordinary exercise in civil engineering. This is Justiniana Prima (modern Caricin Grad in Serbia), built solely to commemorate the sixth-century Emperor Justinian I, born Peter Sabbatius in precisely this corner of the Balkans in the early 480s.1

As emperors go, Justinian is pretty well known, not least because he has left us a range of striking monuments. You don’t have to enjoy

poking around Balkan ruins (as I confess I do) to have your breath taken away by the great cathedral church of Hagia Sophia in modern Istanbul. And the beautiful mosaic panels depicting Justinian and his supporting courtiers on one side, with, opposite, his wife, the Empress Theodora, and hers annually draw thousands of visitors to Saint Vitale in Ravenna. There are also two excellent pen portraits in contemporary sources which agree on all the key points. As the Chronicler Malalas puts it,

He was short with a good chest, a good nose, fair-skinned, curly-haired, round-faced, handsome, with receding hair, a florid complexion, with his hair and beard greying.2

But he is not as well known as he would be, I suspect, had he lived in the first century ad, and the extraordinary nature of his reign makes him well worth his place alongside the stars of I Claudius

Figure I.1

Justiniana Prima, the emperor’s birthplace went from village to regional imperial capital as Justinian sought to memorialize his birthplace.

Introduction

Justinian came to throne in 527, divinely appointed ruler of a self-styled Roman Empire which was still coming to terms with a previous century which had seen its western half evaporate into non-existence. After five hundred years of existence (a time span which puts nineteenth- and twentieth-century European empires firmly into perspective), the largest and longest-lived empire western Eurasia has ever known saw its western provinces fall under the control of a series of foreign military powers in the third quarter of the fifth century: Angles and Saxons in Britain, Franks and Burgundians in Gaul, Visigoths and Sueves in the Iberian peninsula, Vandals and Alans in the western half of North Africa (modern Libya, Tunisia, and Algeria). Italy, the ancient seat of empire, and home, of course, to the city of Rome itself, was ruled by a refugee prince of the Sciri called Odovacar, who had fled to Italy when his father’s kingdom had been destroyed in the 460s and then led a coup d’état which ousted the last Western emperor, Romulus Augustulus, in the summer of 476, after which he pointedly sent the Western imperial regalia off to Constantinople. The intervening half-century before Justinian came to the throne had seen some further changes, of which the most important were the extension of Merovingian Frankish power south and west from an original power base in modern Belgium and Theoderic the Ostrogoth’s conquest of Odovacar’s Italian kingdom between 489 and 493 (Map 1).

The causes of this astonishing imperial unravelling have been intensely debated since the time of Gibbon and before, but recent years have seen the emergence of a revisionist literature which has sought to minimize both the role of outsiders in the events of the fifth century and the amount of violence involved. In this view, various Roman interest groups decided to stop participating in the structures of empire and used semi-outsiders (such as the Franks and Ostrogoths), who were already part of a broader Roman world, to help them negotiate the path to local autonomy. A book about the Emperor Justinian is no place for a full discussion of this hotly debated issue. But in the chapters which follow, we will need to think a bit more about the Vandal-Alans and Ostrogoths in particular, who were targeted by Justinian’s armies, and although the revisionist discourse has gained considerable traction in some scholarly circles, in some important

respects it does not add up to a fully satisfactory account of the overall process of Western imperial dismemberment.

You do find western provincial Roman elites engaged in intense negotiations with rising outside powers (such as Visigoths and Vandal-Alans) already established on Roman soil in the third quarter of the fifth century. But this was the final stage of a several-generation process whose earlier stages—when these groups had first established themselves on Roman soil—had been decidedly violent. Visigoths and Vandal-Alans were new coalitions put together on Roman soil out of manpower deriving from two bouts of unprecedented migration across the imperial frontier (between 376 and 380 and 405 and 408) so that they were in origin outsiders to the empire per se (see Figure I.2). Both forced the Roman state to accept their long-term existence on Roman soil by winning a series of major military victories (such as the nascent Visigothic coalition’s victory at Hadrianople

Figure I.2

Justinian’s uncle and predecessor, the Emperor Justin.

Introduction in August 378 which saw the death of the Emperor Valens and the destruction of two-thirds of his army on one dreadful day). Not only did the creation of these coalitions destroy Roman armies, but acceptance of their existence involved ceding them territories (south-western Gaul to the Visigoths, North Africa—eventually—to the Vandal-Alans) which reduced Western imperial revenues and made it increasingly difficult to sustain large enough military forces to prevent further, militarily driven territorial expansion on the part of the new, emergent power blocs of the Roman West: not just Visigoths and Vandal-Alans but Burgundians and Franks, too, and some smaller migrant groups who also ended up on Roman soil in the different political crises associated with the rise and fall of the Hunnic Empire in the mid-fifth century.

This process undermined central imperial control of the western provinces, drastically reducing the Western Empire’s tax revenues; it also created a new political context in which provincial Roman landed elites had no choice but to do deals with the new kings around them. The wealth of these elites all came in the form of real estate, which made it highly vulnerable, since it could not be moved. If you suddenly found that a Frankish or a Gothic king was the most important ruler in your vicinity, you simply had to do a deal with him, if you could, or risk losing everything. Such deals always involved some financial losses, in fact, but the threat was there—as clearly happened in Roman Britain and north-western Gaul, where pre-existing Roman elites utterly failed to survive the fifth-century collapse—that they might lose the entirety of their wealth, and losing something was infinitely preferable to losing everything. But to describe this, overall, as a largely peaceful and voluntary process of imperial collapse is, to my mind, to privilege the final element of the story over the total picture which emerges from the whole body of relevant evidence.3

Through all this fifth-century mayhem, however, which included its own large-scale outside attacks, particularly in the heyday of Attila’s Hunnic Empire in the 440s, the eastern half of the Roman Empire stood firm. For reasons explored in chapter 1, by the late third and fourth centuries it had become common for the vast stretches of the later Roman world to be governed by more than one emperor from two political centres: Constantinople in the East and Trier on the Rhine or Milan/Ravenna

in northern Italy in the West. Eastern and Western emperors often quarrelled and sometimes fought, but it remained firmly one empire as demonstrated by its overarching legal and cultural unities, which the rise and fall of different imperial regimes never threatened.4 And whereas central imperial authority in the West was eventually destroyed by the loss of too much of its provincial tax base (the loss of the rich North African provinces to the Vandal-Alans in the 440s being a moment of particular disaster), Constantinople retained its key tax-producing territories more or less intact. Egypt, Syria, Palestine, and western Asia Minor (modern Turkey) were the economic powerhouse of the Eastern Empire, and Attila’s armies, though brutally successful on the battlefield, were never able to get past Constantinople and out of the Balkans.

As a result, the state inherited by Justinian in 527—even if it was centred on the eastern Mediterranean and run by largely Greek-speaking elites—retained its characteristically late Roman cultural and institutional structures. This surviving eastern half of the Roman world was governed by recognizably the same basic means and operated with the same broad mechanisms of economic organization as the old whole had done before the disasters of the fifth century. It was also recognizably still an imperial power with greater resources than those available to any of the new western successor kingdoms. This changed, in fact, only in the seventh century, when the Eastern Roman Empire suffered a similar fate to that of the West. Somewhere between two-thirds and three-quarters of its territories fell into the hands of the rampant armies of newborn Islam, exploding out of the sands of the Arabian desert, and what survived was forced to transform itself—culturally, economically, and institutionally— in such profound ways that it is best regarded from this point as another successor state, like the early medieval western kingdoms, rather than as a further direct continuation of the old Roman Empire. This is why many historians, myself included, prefer to use the term Byzantine Empire to differentiate this post-Islamic eastern successor state from the eastern half of the Roman Empire which preceded it.5

But if the prevailing zeitgeist of the mid-first millennium ad was one of Roman imperial disintegration, the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the fifth century being followed by the evisceration of its eastern

counterpart in the seventh, someone clearly forgot to tell the young Peter Sabbatius. By the time of his death in 565, well past the age of eighty, Constantinople’s armies had not only prevented any eastern replay of fifth-century Roman territorial losses in the West but, ably commanded by Justinian’s famous general Belisarius, had even put the process decisively into reverse. Unlike his emperor, no picture of Belisarius survives from antiquity, but he is said to have been tall and handsome, with a fine figure, cutting rather a dashing contrast, one imagines, to the diminutive, balding Justinian (see Figure I.3).6 But however much an odd couple in physical terms, emperor and general together brought the old North African provinces conquered by the Vandal-Alans, Sicily, and Italy, the north-west Balkans, and even parts of southern Spain back under central Roman control, even if this was now the Eastern Roman Empire of Constantinople. Also, two of the early ‘barbarian’ successor kingdoms of the West—the Vandals and the Ostrogoths—were utterly extinguished. These extraordinary events prompt two fundamental questions about the reign of Justinian. By the mid-530s, in the tenth year of his reign, Justinian’s propaganda was claiming that his burning desire all along had been to restore the western territories lost in the fifth century to Roman control, a claim which, up to the 1980s, was generally taken very much at face value, although more recent literature has become much more sceptical.7 There is also not the slightest doubt that his conquests put huge strains on the human and financial resources of the core eastern provinces of his empire, as well as causing death and dislocation on a massive scale in the territories at which they were directed. Justinian even persisted with his western ambitions when the whole Mediterranean world was gripped by an outbreak of plague in the 540s. For many commentators, therefore, even those taking a positive view of Justinian as romantic Roman imperial visionary, the overall balance sheet of his reign raises serious questions. Given all the strain, death, and destruction, were Justinian’s conquests in any sense worth it? The conquest of Italy eventually took the best part of twenty-five years, but within a decade of Justinian’s death, most of its northern plains fell swiftly into the hands of invading Lombards. Still worse, the early seventh century saw an utterly unprecedented series of disasters much closer to home. The

core revenue-generating heartlands of Constantinople’s Eastern Roman Empire—Syria, Palestine, and Egypt—fell first temporarily into the hands of the Persians and then permanently to the armies of Islam, reducing Constantinople from capital of a world empire to a regional power at the north-eastern corner of the Mediterranean. This raises the very real possibility that Justinian’s obstinate campaigning had so overstretched

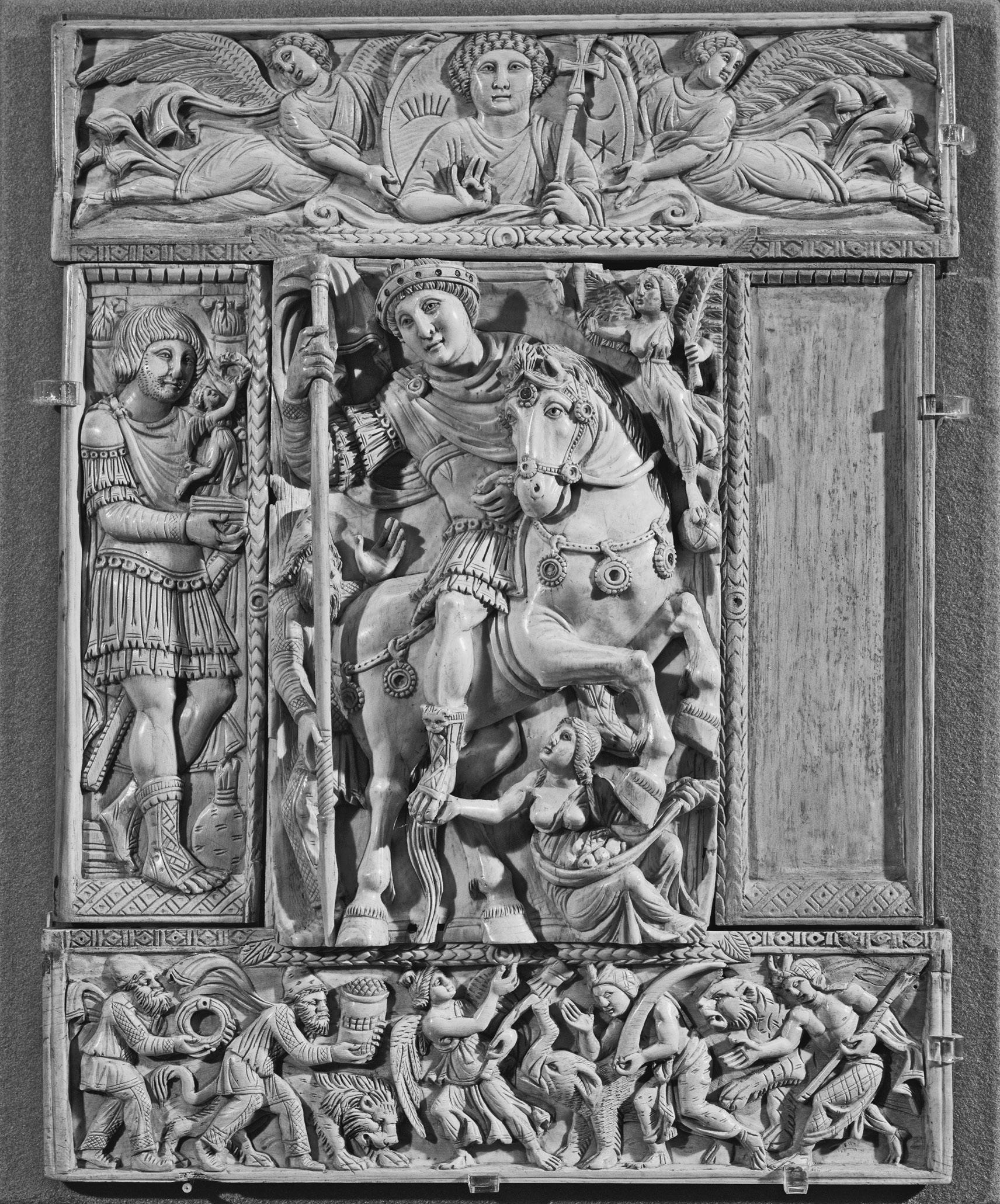

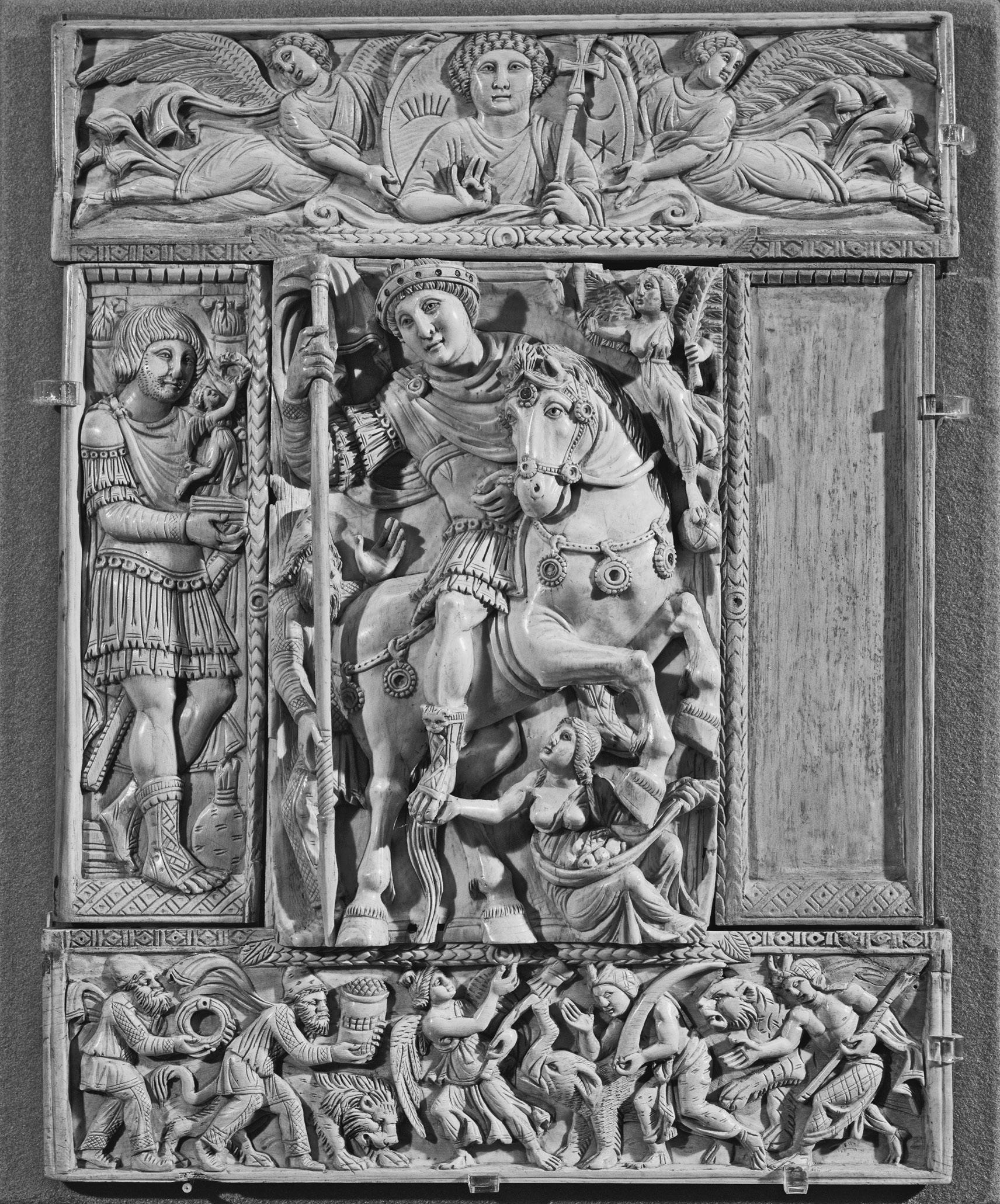

Figure I.3

A triumphant Justinian conquering submitting ‘barbarians’ in the famous Barberini ivory diptych. Credit: © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

his empire’s resources as to make it an easy target for outside predators. Alongside visions of Justinian as a romantic visionary, therefore, you often find the supposition that his campaigns of western conquest fatally damaged the internal structures of his empire. It is the central purpose of this book to explore how much truth there might be in either of these received images of the age of Justinian.

EMPEROR AND HISTORIAN

To allow us to explore these two fundamental questions which lie at the heart of any overall judgment on the extraordinary historical phenomenon which is Justinian, a wide range of sources is available. Apart from the physical evidence of Justinian’s still-standing buildings, like Hagia Sophia in modern Istanbul (there are other churches, too), a vast body of recent archaeological evidence now makes it possible to explore not only particular sites, like Justiniana Prima, but the general functioning of the society and economy over which the emperor presided. There are also smaller physical survivals besides, from exquisite silver plate to coins to manuscript illuminations and mosaics. And while certainly in the midst of important processes of cultural transformation, most of the traditional genres of classical culture continued to flourish. As a result, important poetic, philosophical, and even grammatical works have come down to us from the mid-sixth century, some of which, like the epic Latin poetry of Corippus, play an invaluable role in narrative reconstruction and help to establish the general cultural context of the reign.8 If nothing else, too, Justinian was an emperor who liked to legislate, and a vast, hugely valuable corpus of legal rulings survive from his reign, illustrating not only Justinian’s responses to practical issues but—equally important—the rhetorical justifications in which he couched them (which perhaps bore little relationship to the real reasons behind them). The mid-sixth century also witnessed an important phase in the continuing development of the still nascent Christian religion. Justinian, again, played a major role in church affairs, not least in convening the fifth ecumenical council of the entire Christian Church in Constantinople in 553. So Christian authors—not

just in Latin and Greek but also in oriental Christian linguistic traditions such as Syriac and Coptic—have much to tell us about his reign.9 And often, particularly in the then still developing genre of ecclesiastical history, supplemented by the increasingly influential fashion of writing chronicles of world history starting from creation and working their way down to the present day, church writers were concerned with far more than what we now might think of as religious history, offering valuable insights into political and military events as well.10 As will become clear, religious policy could never be divorced from the other dimensions of imperial activity in Justinian’s Christian empire, so that even apparently more straightforward religious matters turn out to be deeply entwined with the wars of conquest.

That said, this is fundamentally a book about the wars of Justinian: an attempt to provide narrative and analysis of their causes, course, and consequences. As such, it has to depend on one type of source material above all: the ancient genre of classicizing historiography with its ruthless focus on war, politics, and diplomacy. A whole run of authors from the later third to the early sixth century, writing mainly in Greek but also including Ammianus Marcellinus in Latin, provide detailed contemporary narratives of the structures of Roman imperialism in action.11 As a whole, they provide a bedrock understanding of what the empire actually was and how it functioned in practice, on which any thoroughgoing analysis of Justinian’s regime and its actions will need to be based. And for Justinian’s reign itself, several different exponents of this specialized art provide much of the specific information we have about his conquests. The annoyingly wordy and numerically hyperbolic, if otherwise wellinformed Agathias, known to us also as a poet, completes the story of Justinian’s wars, recounting the final campaigns of the mid-550s in Italy and the East. A military officer by the name of Menander, whose fabulously detailed and precise work sadly survives only in excerpts, likewise covers the emperor’s final years, providing diplomatic information of the highest quality.12 But there is one classicizing historian in particular who must stand centre stage in any account of Justinian and his regime, whose work both Agathias and Menander set themselves to continue: Procopius of Caesarea.

Introduction

Procopius doesn’t tell much about his own background, but he clearly belonged to the Eastern Empire’s landowning gentry. His works make it clear that he had enjoyed the extensive private education in classical Greek language and literature which was the preserve of his class (and above). Since he appears in his own writings as an assessor legal advisor—to Justinian’s most famous general, Belisarius, he must then have moved on to legal studies, the costs of which again confirm the kind of privileged background from which he came. It was Belisarius, with Procopius in tow, who led first Justinian’s conquest of Vandal Africa (in 533) and then the initial phases of the war in Italy. Our historian was thus an eyewitness to and occasional active participant in some of the events at the heart of this book.13

Procopius’s account of Justinian’s reign takes the form of three separate works. The longest is a dense narrative history of Justinian’s wars focusing on the years 527–52/3. Books 1 through 7, taking the story down to around 550, were published together in 551; book 8, covering subsequent fighting in Italy and the East, followed in 553. They were all written according to the literary conventions governing this type of classicizing history in the late Roman period, which gives them some peculiar features. You were not allowed to use any vocabulary which had not been sanctioned by the ancient, founding Greek grammarians of the classical period. Amongst other things, this meant finding alternative words for Christian bishops, priests, and monks, none of whom had existed in Athens in the mid-first millennium bc. Introductory digressions to amuse and show off learning, rather than actually explain anything, were de rigueur, and subject matter was strictly prescribed. Characteristic of the genre was an unrelenting focus on military and diplomatic history, and it had become customary, though not essential, for an author to have participated personally in some of the events he describes, both to provide extra interest and to guarantee its essential accuracy.14

Procopius was well aware of the limiting effects of some of these conventions, complaining at one point that he wasn’t allowed to discuss Justinian’s religious initiatives in the same breath as the wars of conquest. But the genre poses other problems, too, of which our author was much less aware. Not least important, in his first seven books Procopius chose