Rites,rightsandrhythms:agenealogyofmusical meaninginColombia'sblackpacificQuintero

https://ebookmass.com/product/rites-rights-and-rhythms-agenealogy-of-musical-meaning-in-colombias-black-pacificquintero/

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Art and authority: moral rights and meaning in contemporary visual art First Edition Gover

https://ebookmass.com/product/art-and-authority-moral-rights-andmeaning-in-contemporary-visual-art-first-edition-gover/

ebookmass.com

War: A Genealogy of Western Ideas and Practices Beatrice Heuser

https://ebookmass.com/product/war-a-genealogy-of-western-ideas-andpractices-beatrice-heuser/

ebookmass.com

Multi-Owned Property in the Asia-Pacific Region: Rights, Restrictions and Responsibilities 1st Edition Erika Altmann

https://ebookmass.com/product/multi-owned-property-in-the-asiapacific-region-rights-restrictions-and-responsibilities-1st-editionerika-altmann/ ebookmass.com

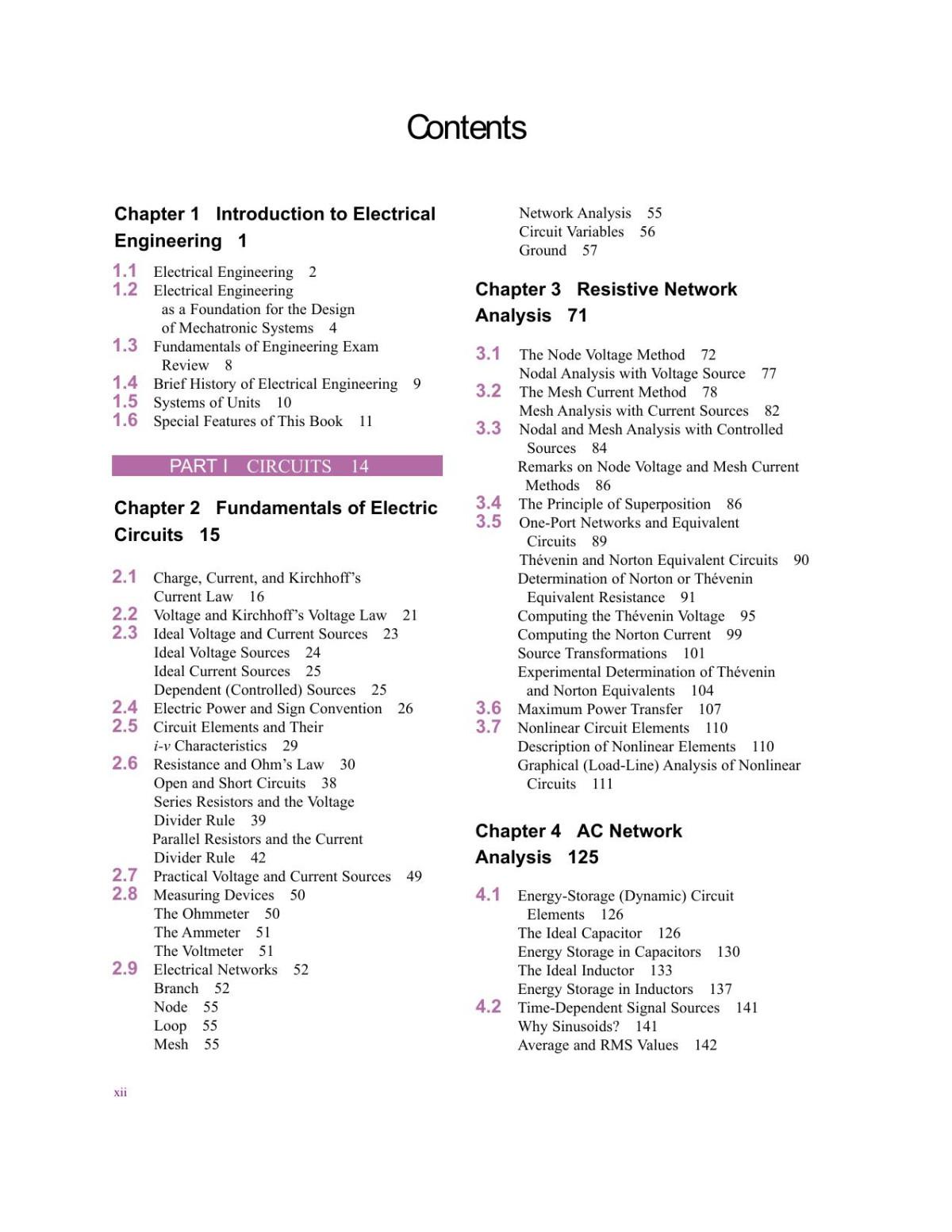

Principles And Applications Of Electrical Engineering 4th Edition

Giorgio Rizzoni

https://ebookmass.com/product/principles-and-applications-ofelectrical-engineering-4th-edition-giorgio-rizzoni/

ebookmass.com

Why Should Guys Have All the Fun?: An Asian American Story of Love, Marriage, Motherhood, and Running a Billion Dollar Empire Loida Lewis

https://ebookmass.com/product/why-should-guys-have-all-the-fun-anasian-american-story-of-love-marriage-motherhood-and-running-abillion-dollar-empire-loida-lewis/ ebookmass.com

Confronting Peace: Local Peacebuilding in the Wake of a National Peace Agreement 1st Edition Susan H. Allen

https://ebookmass.com/product/confronting-peace-local-peacebuildingin-the-wake-of-a-national-peace-agreement-1st-edition-susan-h-allen/ ebookmass.com

Living Well with Graves' Disease and Hyperthyroidism: What Your Doctor Doesn't Tell You That You Need to Know ( John Johnson Protocol for Thyroid disease ) 1st Edition Mary J Shomon

https://ebookmass.com/product/living-well-with-graves-disease-andhyperthyroidism-what-your-doctor-doesnt-tell-you-that-you-need-toknow-john-johnson-protocol-for-thyroid-disease-1st-edition-mary-jshomon/ ebookmass.com

A New Dawn for Politics 1st Edition Alain Badiou

https://ebookmass.com/product/a-new-dawn-for-politics-1st-editionalain-badiou/

ebookmass.com

Adult Psychopathology and Diagnosis 8th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/adult-psychopathology-and-diagnosis-8thedition-ebook-pdf/

ebookmass.com

A review of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) based on current evidence Li-Sheng Wang

https://ebookmass.com/product/a-review-of-the-2019-novel-coronaviruscovid-19-based-on-current-evidence-li-sheng-wang/

ebookmass.com

Rites, Rights & Rhythms

ALEJANDRO L. MADRID, SERIES EDITOR

WALTER AARON CLARK, FOUNDING SERIES EDITOR

WALTER AARON CLARK, SERIES EDITOR FOR CURRENT VOLUME

Nor- tec Rifa!

Electronic Dance Music from Tijuana to the World

Alejandro L. Madrid

From Serra to Sancho:

Music and Pageantry in the California Missions

Craig H. Russell

Colonial Counterpoint:

Music in Early Modern Manila

D. R. M. Irving

Embodying Mexico: Tourism, Nationalism, & Performance

Ruth Hellier-Tinoco

Silent Music:

Medieval Song and the Construction of History in Eighteenth- Century Spain

Susan Boynton

Whose Spain?

Negotiating “Spanish Music” in Paris, 1908–1929

Samuel Llano

Federico Moreno Torroba:

A Musical Life in Three Acts

Walter Aaron Clark and William Craig Krause

Representing the Good Neighbor

Music, Difference, and the Pan American Dream

Carol A. Hess

Danzón

Circum-Caribbean Dialogues in Music and Dance

Alejandro L. Madrid and Robin D. Moore

Agustín Lara

A Cultural Biography

Andrew G. Wood

Music and Youth Culture in Latin America

Identity Construction Processes from New York to Buenos Aires

Pablo Vila

In Search of Julián Carrillo and Sonido 13 Alejandro L. Madrid

Tracing Tangueros

Argentine Tango Instrumental Music

Kacey Link and Kristin Wendland

Playing in the Cathedral Music, Race, and Status in New Spain

Jesús A. Ramos-Kittrell

Entertaining Lisbon

Music, Theater, and Modern Life in the Late 19th Century

Joao Silva

Music Criticism and Music Critics in Early Francoist Spain

Eva Moreda Rodríguez

Carmen and the Staging of Spain

Recasting Bizet’s Opera in the Belle Epoque

Michael Christoforidis

Elizabeth Kertesz

Discordant Notes

Marginality and Social Control in Madrid, 1850-1930

Samuel Llano

Rites, Rights and Rhythms

A Genealogy of Musical Meaning in Colombia’s

Black Pacific

Michael Birenbaum Quintero

Rites, Rights & Rhythms

A GENEALOGY OF MUSICAL MEANING IN COLOMBIA’S BLACK PACIFIC

Michael Birenbaum Quintero

1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Quintero, Michael Birenbaum, author.

Title: Rites, rights & rhythms : a genealogy of musical meaning in Colombia’s black pacific / Michael Birenbaum Quintero.

Description: New York : Oxford University Press, [2019] | Series: Currents in Latin American and Iberian music | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018032429 (print) | LCCN 2018035028 (ebook) | ISBN 9780199913930 (updf) | ISBN 9780190903213 (epub) | ISBN 9780199913923 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780199913947 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Folk music—Colombia—History and criticism. | Blacks—Colombia—Music—History and criticism. | Blacks—Colombia—Social conditions.

Classification: LCC ML3575.C7 (ebook) | LCC ML3575.C7 Q54 2018 (print) | DDC 781.6409861—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018032429

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Paperback printed by WebCom, Inc., Canada

Hardback printed by Bridgeport National Bindery, Inc., United States of America

For my parents.

For the memory of my grandfather, Phillip B. Roth.

For Kenan, hombre del Pacífico.

For the people of the Colombian Pacific.

For the memory of José Antonio Torres and Alicia Camacho Garcés.

Community of Punta del Este, Buenaventura. Arrullo for the Vírgen del Carmen, 2017.

Contents

Acknowledgments ix

About the Companion Website xv A Note on Images xvii

Introduction 1

1. The Sounded Poetics of the Black Southern Pacific 27

2. Music in the Mines: Black Cosmopolitans and Musical Practice in the Colonial Southern Pacific 61

3. Modernities and Nonmodernities in Black Pacific Music 115

4. Race, Region, Representativity, and the Folklore Paradigm 161

5. Between Legibility and Alterity: Black Music and Self-Making in the Age of Ethnodiversity 213

Conclusion 275

References 281

Index 309

Acknowledgments

I’ve been going back and forth to Colombia for more than fifteen years now, and it’s increasingly impossible to disentangle those to whom I’m thankful for contributing to this project and those to whom I’m grateful for passing through my life (some of whom, by now, have passed beyond this life). There are also people whose privacy I will protect by not thanking. This list is something like a kinship map of most of my life, and could never be comprehensive—but I’ll try.

I am profoundly grateful to my academic mentors and interlocutors during grad school. My dissertation committee: Ana María Ochoa, Jairo Moreno, Aisha Khan, Jacqueline Nassy Brown, and George Yúdice. My New York University (NYU) professors: Gage Averill, Mike Beckerman, Arlene Dávila, Fred Myers, Diana Taylor, Suzanne Cusick, J. Martin Daughtry, Maureen Mahon, David Samuels, Mercedes Dujunco, Kyra Gaunt, and Jason Stanyek. My fellow grad students: Christopher Ariza, Bill Boyer, Danielle Brown, Amy Cimini, Ryan Dorin, Michael Gallope, Ivan Goff, Monica Hairston, Clara Latham, Winnie Lee, Yoon- Ji Lee, Dan Neely, Brett Pyper, Scott Spencer, Ben Tausig, Eric Usner, and Wynn Yamami. I owe much to Jan Maghinay Padios. Ethnomusicologist Lise Waxer was particularly supportive of this project, and I’m saddened that she passed away prematurely, before seeing her encouragement come to fruition.

I also want to thank members of the New York Colombian musical community, especially Sergio Borrero, Lucía Pulido, Pablo Mayor, and Martín Vejarano. The

Acknowledgments

NYU departments of music and performance studies, as well as the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies, supported a series of workshops taught by the Colombian musicians Irlando “Maky” López and Maestro Gualajo (José Antonio Torres). Two semesters of dissertation writing were funded by a fellowship from the NYU Humanities Initiative, where I was privileged to talk with Marcela Echeverri, Alex Galloway, Bambi Schifflin, Jane Tylus, and others. A Mellon PostDoctoral Fellowship in Concepts of Diaspora at John Hopkins Univeristy provided me with generous interlocutors in Gabrielle Speigel, Juan Obarrio, Emma Cervone, Deborah Poole, Andrew Talle, Anand Pandian, Clara Han, Naveeda Khan, Valeria Procupez, Isaías Rojas Pérez, Veena Das, Bode Ibironke, Sana Aiyar, and Maya Ratnam.

At Bowdoin College, Mary Hunter was an invaluable mentor, and I’m grateful for my time there with Tracy McMullin, Vin Shende, Femi Vaughan, Krista Van Vleet, Allen Wells, Judith Casselberry, Jessica Marie Johnson, Charlotte Griffin, Marcos López, and many other colleagues, friends, and students. My colleagues at Boston University have been tremendous, especially Marié Abé, Jeff Rubin, Julie Hooker, Adela Pineda, Louis Chude- Sokei, Saida Grundy, Ashley Farmer, Ben Seigel, John Thornton, Victor Coelho, and Brita Heimarck.

Thanks to all those who crossed my path along the way and took the time to talk: Ana María Arango, Santiago Arboleda, Medardo Árias, Margarita Aristizábal, Kiran Asher, Paul Austerlitz, C. Daniel Dawson, Michael Iyanaga, Agustín Lao Montes, Claudia Leal, Robin Moore, Paola Moreno Zapata, David Novak, Juan Sebastián Ochoa, Ulrich Oslender, Deborah Pacini Hernández, Tianna Paschel, Eduardo Restrepo, Anne Rasmussen, Jonathan Ritter, Axel Rojas, Matt Sakakeeny, Carolina Santamaría, Gavin Steingo, Carlos Valderrama, Peter Wade, Fatimah Williams Castro, Debbie Wong, and Catalina Zapata Cortés. Having gifted students who keep me on my toes has been a true privilege: Carlos Alberto Velasco, Patricia Vergara, Walker Kennedy, Ian Coss, and Brian Barone— who also provided life- saving editorial grunt work for this book.

Suzanne Ryan and Alejandro Madrid have been true allies to this book, and I appreciate Walter Clark’s influence as well. A Minority Book Subvention Grant from the Society for Ethnomusicology has also been instrumental.

My fieldwork in Colombia was supported by a Tinker Foundation summer grant administered by the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at NYU and a Fulbright Institution of International Education (IIE) grant. The staff of the Comisión Fullbright in Bogotá were important in the logistics of this project. I originally went to Colombia to work with champeta music; Edgar Benítez,

Acknowledgments xi

Elizabeth Cunín, and the late Adolfo González provided important support, despite the fact that I switched coasts on them.

In Bogotá, I found important resources and crucial interlocutors. At the Ministry of Culture, Alejandro Mantilla, Leonardo Garzón, Doris de la Hoz, and Marta Traslaviña; Jaime Quevedo of the Centro de Documentación Musical, and Leonardo Bohórquez at ICANH (the Colombian Institute of Anthropology and History), then also the base for Mauricio Pardo. Thanks to Carlos Miñana, Egberto Bermúdez, Jaime Arocha, and Susana Friedmann.

Cali is a city very dear to my heart and history, and so are many of its inhabitants. Fernando Urrea, Mario Diego Romero, Darío Henao, Renán Silva, and the doctoral students in humanities at UniValle, as well as Aurora Vergara at ICESI University and Manuel Sevilla at Universidad Javeriana have been essential. Germán Patiño (RIP) and other functionaries at the Petronio Álvarez Festival were generous with their time. In Buenaventura: Lucy Mar Bolaños, Hebert Hurtado, and Carlos Palacios at the Universidad del Pacífico. Jorge Idárraga is a friend, a collaborator, and a gifted photographer whose work I’m proud to include in this book.

This project would have been unthinkable without the collaboration of many, many musicians, culture workers, dancers, teachers, instrument makers, and academics. Thank you to Estreisson Agualimpia; Los Alegres del Telembí; Juana Álvarez; Olga Angulo; Leonidas “Hinchao” Valencia, Jackson and Panadero, Neibo Moreno (RIP), Heriberto Valencia, and the members of ASINCH; Marta and Diego Balanta; Fortunata Banguera; Pacho Banguera (RIP); Begner and Manuel of Herencia; Esperanza Bonilla; Samuel Caicedo (RIP) and Oliva Arboleda; Pascual Caicedo and family; Cali Rap Cartel and the rappers in Charco Azul, especially Fernando; the members of Grupo Canalón, especially Nidia Sofía Góngora and July “Chochola” Castro, saludos to Moño, Hermés, Moisés, Celia, and Ñaño; Mauricio Camacho; Isaís “Saxo” Carabalí; Juan Davíd Castaño; Tostao, Goyo, and Alexis of Chocquibtown; Carlos Colorado; Esteban Copete; Baudilio and Alí Cuama; Enrique Cundumí; Douglas from Orilla; Alex Duque and Tamborimba; doña Daira and Ferney; Epifa; Mayor Ernesto Estupiñan and Katia Ovidia in Esmeraldas, Ecuador; Daniel Garcés; Humberto and Jhon Jairo Garcés; doña Teodocia García “Tocha”; don Agustín García; Hugo Candelario González; Esteban González; Libia Grueso and Conti; Marino Grueso; Liliana Guevara; Victor Guevara; Myrna Herrera; Teodora Hurtado; Juancho López and Cristian; Alexis Lozano; “El Negro” Cecilio Lozano (RIP); Magnolia; Naka Mandinga; Zulia Mena; Markitos Micolta; Hugo Montenegro Manyoma; Joselín Mosquera; Juan de Dios Mosquera; Sergio Mosquera; Nancy Motta; Zully Murillo; la profe Nelly; Octavio Panesso; Madolia de Diego Parra (RIP); Heliana Portes de Roux; Addo

Acknowledgments

Obed Possú “Katanga”; Alfonso Portocarrero; doña Raquel Portocarrera; Carlos Rosero, Julio, Elizabeth, and Yosú of Proceso de Comunidades Negras in Bogotá; Augusto Perlaza and the Chirimía del Río Napi; Erney, Larry, Armando, Quique, Lucho, and César of Quilombo; Fanny Quiñonez; Enrique Rentería; Victor Hugo Rodríguez; Ernesto Santos; Urián Sarmiento; Raquel Riascos; Hector Sánchez; doña Lycha Sinisterra; Benigna Solís; Alirio Suárez; the Torres family in Sansón, especially don Genaro and don Pacho; doña Eulalia Torres; Jayer Torres; Jacobo Torres and La Mojarra Eléctrica; Tumbacatre; Hector Tascón; Rocky Telles; Enrique Urbano Tenorio “Peregoyo” (RIP) and doña Inéz; Taincho; Delio Valencia and Chencho; Miguel Vallecilla; and Alfredo Vanín. I am deeply grateful to the late Alicia Camacho Garcés, whose knowledge and warrior spirit continue to inspire.

I also learned from sharing daily life and countless other experiences with generous and hospitable people. Thank you: Hernán and Paola in Bogotá; Carlos Valentierra, Jader Gómez, Rocío Caicedo, Katty, and Joanna; Astolfo, Juan Peter, and Zully; Rocky, Silvio Gabino, Atlético Pacífico, and the Galaxcentro crew (not to mention Mulenze, La Ponceña, Guararé . . .)! Christopher Dennis, John Myers, Tara Murphy, Chucho Hernández, and Mike Shoemaker— the gringada. Washington, Yuuiza, Ana Bolena; the Bonilla family, especially Clemira Bonilla, Oliva Bonilla, doña Sixta (RIP), Power, doña Dora, Kevin, doña Luz, Yoly, Nanín, Nicol and Wendy, Richard Bonilla, Miguel Bonilla. Officer Zuluaga, and the personera in Santa Bárbara literally saved my life.

In San José, doña Agripina and Faizuri. Thank you to Yineth. The Obregón family, especially el profe Hugo Obregón and his family and Mayán; the Caicedo family, especially Pascual; Enrique and his group; Pájaro in Guapi; Aquino in Mariano Ramos; doña Alba and Lucy; the Angulo family—doña Francy, Hawer, Chava, Arbey, and Carol, thank you for your friendship; doña Otilia, Gerónimo, and Seviliana, Cuchi (RIP), Cocora (RIP), doña Dalia, Pirobo, Proyecto, and Encho; Ober; doña Rosa, doña Blancura; and Javier and Gacho. Saludos to the whole Aramburo family, as big as it is: doña Aura, my compadre Harinson and his family, Astolfo, el Negro, Noemi, Ros Ester (RIP), Emilsen, Harlin, Viviana, and don Zaca (RIP).

I want to single out some of the musicians who were my primary teachers and who continue to contribute to my growth as a musician and an academic alike. Juana Angulo (RIP), Ana Hernández, Carlina Andrade, and Gladys Bazán: the Cantadoras del Pacífico. Maky López and Diego Obregón are my teachers and my friends, and I thank them for both. José Antonio Torres, maestro Gualajo, who gave me so much, died as this book went to press. I, and the many others who he has touched with his music and his mischievous spirit, miss him tremendously.

Acknowledgments xiii

This project has often taken me away from you, Aura and Kenan, but you are at the center of it. Thanks for sticking with me.

To all of the people who made this possible: I hope I have described this music and this world in a way that approaches a truth that you recognize and believe; I hope my work can begin to reflect all that you have taught me.

Cali, Colombia

May 2018

About the Companion Website

URL: www.oup.com/us/ritesrightsrhythms

Username: currulao

Password: chonta

Oxford University Press has created a password-protected website to accompany Rights, Rites, and Rhythms. The site includes photos, audio, video, and supplemental resources, organized to correspond with the book’s chapters. Examples available online are indicated in the text with Oxford’s symbol

A Note on Images

All the photographs in this book, unless otherwise indicated, were taken by the Buenventuran photographer Jorge Idárraga. For more information about Idárraga and his work, visit Jorge Idárraga on Facebook or contact him at idarragapublicidad@yahoo.es. Maps were created by J. D. Kotula at Boston University Libraries.

Map 1. Colombia.

Rites, Rights & Rhythms

INTRODUCTION

Nidia was livid. It was the height of the ritual music season in the remote Colombian Pacific village of Timbiquí, and in the town square, thronged by their fellow townspeople, she and a dozen or so other friends were singing and playing ritual music—or rather, attempting to. Squinting angrily and pointing her guasá shaker at one of the little saloons on the town square, she yelled, “I can’t hear myself sing with that goddamn stereo playing so loud. I can’t even hear the drums!” Curiously, the music blasting from the saloon was itself traditional music, recorded by many of the same people trying to play in the plaza. The recorded voice above which Nidia struggled to be heard was, in fact, her own.

Rights, Rites, and Rhythms examines this kind of feedback, interference, and overlap between the various experiences of local currulao music—as ritual, folklore, popular music, identity-marker, and political resource—among the black inhabitants of Colombia’s southern Pacific coast. The complexity of these interactions is a product of the friction between the kinds of temporality that they are taken to embody and the points along the historical trajectory of the southern Pacific at which they emerged: the ancestral past, the dislocations of the modern present, and the political struggle for a future that integrates both. Therefore, this book relies on both ethnography and historical research to trace the emergence, development, maintenance, and in some cases abandonment of the systems of meaning that frame these musical sounds. It also describes how this history of

musical meaning manifests itself in current musical practice. Thus, the book serves as a genealogy of what—and how—black southern Pacific music means today.

Nidia’s struggle to be heard over her own recorded voice suggests familiar regimes of authenticity and a somewhat facile opposition of the human against the technologically mediated. Other cases in the book turn that binary inside out. The traditional chigualo ceremony, a child’s funeral- cum- fertility rite, might be celebrated these days with recorded reggaetón music rather than the old drumming and song-games, which are often consigned to the performances of folkloric dance troupes. In this case, ritual function and sociality have been folded into an entirely new set of sonorities, while the old sonorities are refashioned into markers of a ritual function that they no longer have.

This marking, however, has functions of its own. Currulao is often Exhibit A in claims by the Afro- Colombian social movement about the ethnocultural distinctiveness of the black Pacific. The movement has parlayed these claims into state legislation of collective territory and other culturally based rights for the people of Timbiquí and other black communities in the Pacific rainforest. Meanwhile, the Colombian state has provided venues for currulao music, in the interest of expanding its own influence in the Pacific region and of demonstrating to international bodies its commitment to Afro- Colombian human and cultural rights, in the context of violent armed conflict and the massive displacement of black communities in the Pacific. All of this puts currulao music— as rites, rights, and rhythms— at the center of contestations over blackness and its place in the Colombian nation.

This book is about musical meaning, specifically the musical practices of black people living on Colombia’s southern Pacific coast. These musical practices are imbricated within a number of different systems of meaning, often simultaneously. A song in praise of a saint may also hold meaning as an example of regional folk culture, as supposed evidence of black backwardness, or as a political claim. Approaching these questions of musical meaning requires both a historical approach, to uncover the genealogies through which these meanings become sedimented, and an ethnographic approach, to understand the ways in which both the practitioners and the publics of these musical practices apprehend the various resonances which these histories of meaning have.

Therefore, this book is both something of a historically informed ethnography and something of an ethnographically informed history. By “ethnographically informed history,” I do not mean only that I have used ethnography as a source for the writing of history. I also mean that I have intended, when possible, to bring an ethnographer’s sense of the importance of the everyday into the examination of the past. By “historically informed ethnography,” I mean simply that I have

3 examined people’s actions in the present and understood them as informed (although not determined) by history.

A central field of meaning for currulao music is its close association with blackness. Examining the historical processes by which this music came to be understood as black provides a view into how the people of the southern Pacific came to be black.1 Of course, I do not mean the term black in the physiognomic sense; the Pacific region is overwhelmingly populated by the descendants of Africans and Colombians. But the notion of blackness in the Pacific as a racial, ethnic, regional, cultural, and political constituency—glossed in recent usage as AfroColombian is not as self-evident as it might seem from a vantage point here in the United States, where the inscription of absolute difference between black and white is both primordial and persistent. Black Colombians in the southern Pacific share an African cultural heritage and the historical experiences of enslavement, marginalization, and struggles with other black populations, but the specific meaning of blackness, the terms in which it is lived, or the relative weight of those terms, is not the same as in the United States, Brazil, or the Caribbean—or even Colombia’s Caribbean coast.

Omi and Winant’s term racial formation2 is useful because its possibilities for being used in the plural provide a helpfully relativizing way of looking at how race is constructed in different settings and what is at stake in those varied constructions. My argument assumes that, although socially real, race is not a selfevident or autonomous fact. As we will see, in the case of the Colombian Pacific, race—like music—is a category interpenetrated by and coconstituted alongside other factors, such as regional, cultural, and political constituencies. As Gary Okihiro has suggested, racial formations are simultaneously subsumed into national, class-inflected, spatial, gendered, and sexual projects—even as race itself remains salient.3

I mention this point because I want to avoid the tendency of race to become a self- fulfilling prophecy, by which the local manifestations of such global projects as white superiority, racialized divisions of labor, modernity, or hierarchies of culture are described with recourse to deterministic racial or cultural teleologies from other settings. I by no means abjure race; rather, I approach it inductively: from the ground up. This is not a matter of what Matory has playfully called “ ‘but among the Bongo-Bongo . . .’ contrarianism,” or what Brown calls the “reduc[tion of] diaspora to ‘another Black community heard from,’ ” although Colombia’s southern Pacific coast does indeed have its particularities and has not been much “heard from”— or listened to.4 Rather, paying attention to local particularities— such as the importance of geographic space and the processes of both the black cultural formation (i.e., ethnogenesis) and racial

interpellation from without (i.e., racialization) in the Colombian context—is key to understanding both national ideologies about race and space and the particular contours of black life in Colombia.

These, in turn, have broader manifestations, such as the consolidation of the Afro- Colombian social movement, which galvanized around the drafting of a new national constitution in 1991 that recognized the nation as “pluricultural and multiethnic” and recognized black Colombians, particularly rural communities in the Pacific, as constituting an official ethnic minority deserving of particular rights. The Afro- Colombian movement also participated in the drafting of Law 70 of 1993, the “Negritudes Law,” which outlined some of the specifics of these rights, most prominently the right for black communities to collectively hold land title over the territories that they have traditionally occupied—a new articulation of the relationship between race and space. The legal recognition of black cultural and territorial rights is one of the most important and influential developments in black politics in the hemisphere, but understanding and deriving political lessons from it for other black populations also require understanding the specificities from which it emerged.

Given the contingency of these processes, in examining the traditional music of the black inhabitants of the southern Pacific, neither music, nor tradition, nor blackness, nor the geographical entity of the southern Pacific should be taken as eternal or as givens, as either a process of imposition or of resistance. Indeed these qualifications are fairly clichéd, suggesting the necessity of a different set of questions. If the sounded poetics traditional to the black inhabitants of the Pacific are not to be taken as given, what are they to be taken as? Or, to move the question out of the rarified zone of ontology, what is the work they do, in both people’s lives and the social and political realms that structure these lives?

Blackness and Invisibility in Colombian Racial Formations

Colombia has a significant black population—indeed, the largest Africandescended population of any Spanish- speaking country in the world, and the third-largest in the hemisphere.5 What for me is even more compelling than the statistic itself is the fact that it is practically unknown, even in Colombia itself. How is it that such a large black population has been “invisibilized”6 for such a long time? What is it about Colombian racial formations that have so emphatically resisted attention? Certainly the size of the black Colombian population is poorly reflected in academic production of research into the descendants of Africans in

the Western Hemisphere.7 There are a number of reasons for Colombia’s absence from academic (not to mention popular or journalistic) understandings of blackness in the hemisphere.

The anthropological canonicity of countries like Brazil, Cuba, and Haiti as the star exponents of New World blackness has largely overshadowed attention to Colombia. In part, this canonicity is heir to the Herskovitsian ranking of various New World black populations in terms of their degrees of African retention, a distinction with strong normativizing and authenticating repercussions—indeed, the role of anthropology as a legitimizing force in ethnocultural mobilizations is discussed throughout this book.8 In Melville J. Herskovits’s ranking of black populations by African retention, the Colombian region of Chocó received an average of D in total Africanness.9 Debating the relative merit (or lack thereof) of Colombia’s inclusion in the anthropological canon of black American10 populations that exhibit the persistence of the “entire strata of African civilizations,”11 or of the usefulness of that criteria of anthropological validity, obviates neither the workings of racism for black Pacific Colombians nor the sense of cultural kinship they feel with their paisanos (people from the same area). This last is not to say that many black Colombians, particularly in urban settings outside the Pacific, do not feel pressure to assimilate and leave these same paisanos behind. Yet even this process is part of a common dynamic, which Wade has described as a continuum between “nucleation” and “dispersal” of black Colombians12 a model that describes not only individual behavior, but also broader dynamics of the conformation of blackness in Colombia.

An even more important key to the invisibilization of black Colombians, both within Colombia itself and relative to certain other nations, is the place of blackness in nation-building. While the regimes of Fulgencio Batista in Cuba, François Duvalier in Haiti, and Getúlio Vargas in Brazil13 needed to cater to some degree to the black urban working classes of their respective nations, Colombia, which was already later than other countries to the kinds of mass-media-aided populism that promoted cultural nationalism in the rest of Latin America, instead descended into a protracted period of civil war14 in the middle of the twentieth century.

At any rate, the overwhelmingly rural black population of the time left few black proletarians to be coopted, even if this had been a priority of the government. Furthermore, as we will see in a moment, the regionalization of race in Colombia folded blackness into a spatial- civilizing project rather than one of political cooptation. Therefore, black Colombians did not emerge as a constituency; rather, blackness in Colombia remained a feature, partly physiognomic and partly behavioral,15 imputed to only particular segments of the population, especially those residing in specific regions of the national territory.