FOREWORD TO FIRST PRINTING

The Brain and Cranial Base: Microsurgical Anatomy and Surgical Approaches

I salute Cardinal Health V. Mueller, Carl Zeiss, Inc., and Medtronic Midas Rex on the occasion of the publication of this book and thank them for the grant that made it possible. Cardinal V. Mueller was added to the list of those whose grants made this second printing possible. Cardinal V. Mueller has been producing microsurgical instruments for decades that allow us to take advantage of the anatomy displayed in this volume. It was my good fortune to begin work with Bill Merz of Cardinal V. Mueller nearly 40 years ago. Bill was among the best instrument makers in the world. Bill and V. Mueller have worked with the leading surgeons of the world and have produced instruments that have contributed greatly to the care of our patients. When I had a need for an instrument to make our work more accurate and safe, Bill Merz immediately sensed the possibilities. He derived great pride and joy from knowing he had met the need for an instrument that improved the outcome and lives of patients. In his later years, Mr. Merz established the William Merz Professorship in the Department of Neurosurgery at the University of Florida. I also salute Carl Zeiss and Medtronic on the occasion of the publication of this book and thank them for the grants that made this and the first printing possible. The increased safety and accuracy, and the improved results obtained with the Zeiss microscope are some of my greatest professional blessings and a great contributor to the quality of life of my patients. Medtronic Midas Rex, through the increased ease and delicacy of bone removal provided by their drills, has also made a worldwide contribution to the care of neurosurgical patients and allowed us to focus on dealing accurately and precisely with the delicate neural tissue that is the basis of our specialty. Midas Rex, Zeiss, and V. Mueller have continued to invest in modifying and upgrading their instruments by integrating them with modern technological advances in order to aid us in our work and provide new benefits to our patients. They have assisted with educational endeavors, like this book, that have improved neurosurgical care on every continent and have made the academic aspects of my career much more rewarding. I am grateful for their support of the publication of our studies on microsurgical anatomy and

for partnering with neurosurgeons throughout the world to improve neurosurgical care (1). As stated in the Millennium and 25th Anniversary Issues of Neurosurgery, this work on microsurgical anatomy has grown out of my personal desire to improve the care of my patients (1, 2). It represents a 40 plus year attempt to gain an understanding of the anatomy and intricacies of the brain that would improve the safety, gentleness, and accuracy of my patients’ surgery.

Before proceeding with some additional thoughts about the role of microsurgical anatomy in neurosurgery, I would like to share some thoughts about neurosurgery, some of which were included in my addresses as President of the AANS and CNS (1, 2). Neurosurgeons share a great professional gift; our lives have yielded an opportunity to help mankind in a unique and exciting way. In my early years, I never imagined that my life would hold as gratifying, exciting, and delicate a challenge as that of being a physician or a neurosurgeon. Neurosurgeons’ work is performed in response to the idea that human life is sacred, that it makes sense to spend years of one’s life in study to prepare to help others. Our training brings into harmony a knowledgeable mind, a skilled set of hands, and a well-trained eye, all of which are guided by a caring human being. The skills we use have been described as the most delicate, the most fateful, and, to the layperson, the most awesome of any profession. The Gallup Poll has reported that neurosurgeons are among the most prestigious and highly skilled members of American society. We share the opportunity to serve people in a unique way, dealing surgically with the most delicate of tissues.

Our ranking among the most highly skilled members of society tends to lead us to forget that our work and success are made possible by the benevolent order built into the universe around us. That people heal and survive after surgery provides us with our work and serves as a constant reminder of this benevolent protective order. We are surrounded by biological and physical forces that could overcome us, outstripping our finest medical and scientific achievements. The momentous process of injured tissues’ knitting together is as essential to the work of the surgeon

as the air people breathe is to their survival. The humanity survives and that neurosurgeons can play a role in the process of healing are examples of the compassion and love that surround us. A patient who writes a thank-you note or praises my efforts leads me to inwardly reflect that one of our greatest gifts is that we were created to help each other. I am grateful for the opportunity to be a participant in the miracle we call neurosurgery.

Another gift we share is a historical one based on the standards set by early physicians. Hippocrates taught that medicine is a difficult art that is inseparable from the highest morality and love of humanity. The noble values and loyal obedience of generations of physicians since Hippocrates have raised the calling to the highest of all professions. Many of us were attracted to neurosurgery by both the meticulousness of surgical craftsmanship and the intellectual challenge posed by modern clinical neurology and neurophysiology. All of us have submitted ourselves to the discipline of rigorous training, possibly the most demanding in modern society, and are capable of giving a great deal of ourselves.

Our work has grown out of the belief in absolute standards of value and worth in humanity. These values are reflected in the increasing importance of one man, one woman, or one child in American society and throughout the world. An example of the evolving importance of the individual is found in examining great human creations such as the Egyptian pyramids and the Great Wall of China. Through the decades and the centuries, humankind has evolved to the point where some of the pyramids of modern society are our modern medical centers. In them, society’s most highly trained teams, using humankind’s most advanced technology at great cost, are allowed to work for days trying to improve the lives of individual patients without regard to whether they are rich or poor. Issues related to the dignity and worth of a single man, woman, and child are clearer to us now than they were a century or two ago and provide the driving force behind our work. These values and standards, which are inseparable from the highest morality and love of humanity, are built into us just as the process of healing is built into our nature.

J. Lawrence Pool, who led the neurosurgery program at Columbia University, wrote, “As I look back on the pattern of my life I see how fortunate it was that I had chosen a career in neurosurgery, which I passionately loved despite its long hours and many grueling experiences.” He concluded with a statement about his belief that the best surgeons have a strong sense of compassion. It is important that we grow in compassion just as we grow in competence. Competence is the possession of a required skill or knowledge. Compassion, on the other hand, does not require a skill or knowledge; it requires an innate feeling, commonly called love, toward someone else. Both competence and compassion need to be developed simultaneously, just as the giant oak develops its root system along with its

leaves and branches. Competence without com- passion is worthless. Compassion without competence is meaningless. It is a great challenge to guide patients competently and compassionately through neurosurgery. Death and darkness crowd near to our patients as we help them search for the correct path. Neurosurgical illness threatens not only their physical but also their financial security, because it is so expensive and the potential for disability is so great. No experience draws more frequently than the performance of neurosurgical procedures on the passage in Psalm 23, “though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death . . . .” Neurosurgeons’ competence should be reflected in our training, knowledge, and skill; our compassion should be reflected in our kindness, sincerity, and concern. The Saints and Buddhas taught that compassion and wisdom, which lead to competence, are one. Our patients are looking for help from someone who is knowledgeable, patient, and wise and who can provide clarity, wisdom, and enlightenment so that they can face life after surgery on the brain. That is the essence of integrating competence and compassion. Neurosurgeons have the responsibility to develop the dialogue in understandable terms to help the patient, the patient’s family, and society understand the meaning of the patient’s illness. One of my personal precepts is, “The best ally in the treatment of neurosurgical illness is a well-informed patient.” Success requires more than advancing and applying medical knowledge. It also requires increased compassion so that we can respond sympathetically and with the best of our knowledge to all of our patients’ questions and provide them with timely information that will help them understand their illness and plan their lives. There comes a time in our work when we can make as much of a difference in each other’s lives by sitting for 30 minutes, for 1 hour, or longer to answer questions as we can by hours in surgery. There is no substitute for an honest, concerned, and sympathetic attitude. Success may not mean that every patient survives or is cured, because some problems are insolvable and some illnesses are incurable. Instead, success should mean giving every patient the feeling that he or she is cared about, no matter how desperate their situation, that their pain is felt, that their anger is understood, and that we care and will do our best. The greatest satisfaction in life comes from offering what you have to give. Devotion and giving to others gives purpose and meaning to life.

Another circumstance leading to the esteem that neurosurgeons enjoy is the magnificent tissue with which we work. The brain is the crown jewel of creation and evolution. It is a source of mystery and wonder. Of all the natural phenomena to which science can draw attention, none exceeds the fascination of the workings of the human brain. The brain holds our greatest unexplored biological frontiers. It is the only organ that is hidden and completely enclosed within a fortress of bone. The brain, although it does not move, is the most metabolically active of all organs, receiving 20% of cardiac output while representing

only 3% of total body weight. It is the most frequent site of crippling, incurable disease. It is exquisitely sensitive to touch, anoxia, and derangements of its internal environment. Its status determines whether the humanity within us lives or dies. It yields all we know of the world. It controls both the patient and the surgeon.

Brain accounts for the mind, and through the mind, we are lifted from our immediate circumstances and are given an awareness of ourselves, our universe, our environment, and even the brain itself. Here, in two handsful of living tissue, we find an ordered complexity sufficient to preserve the record of a lifetime of the richest human experience and create computers that can store amounts of data that can be comprehended only by the mind. Perhaps the most significant achievement of this tissue is the ability, on the one hand, to conceive of a universe more than a billion lightyears across and, on the other, to conceptualize a microcosmic world out of the reach of the senses and to model words completely separate from the reality that we can see,

hear, smell, touch, and taste. Mind and brain are the source of happiness, knowledge, and wisdom. The brain is not the seat of the soul, but it is through the brain and mind that we become aware of our own souls.

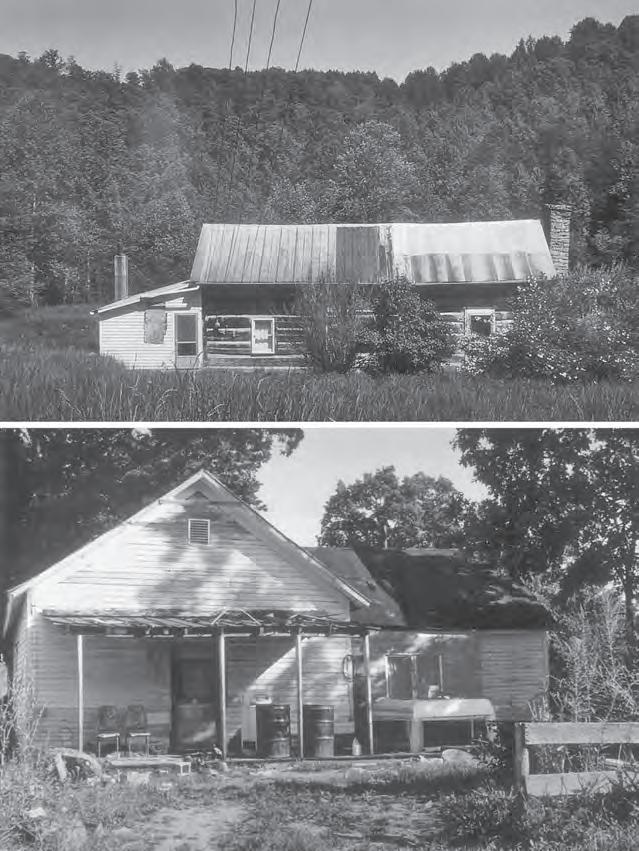

In my early years, never in my wildest flights of imagination did I consider that life would yield such rewarding and challenging work as that of being a physician, and I was unaware that neurosurgery even existed. My early life was without exposure to physicians, hospitals, or other modern conveniences (Fig. 1). My birth was aided by a midwife in exchange for a bag of corn. As I entered college, the goal of being a physician seemed so unattainable that I had not considered that possibility. I first pursued chemistry, but the missing human element led me to major in social work. Social work also failed to satisfy me because it lacked the opportunity to touch and help others by working with the hands. That I might become a physician did not enter my mind until a psychology instructor invited me to see a brain operation performed in his laboratory. To my amazement, a

Figure 1 Author’s early home (A) and elementary school (B).

tiny lesion improved the small animal’s behavior, but without affecting its motor skills. That day, I sensed some of the amazement that must have been experienced in the 1870s when Broca presented his early observations regarding the cerebral localization of speech in his patient, Tan, and when Fritsch and Hitzig described their experiments on the cerebral motor cortex. Before their time, interest in the brain and its function centered on philosophical discussions of the brain as the seat of the mind and the soul and not as a site possessing the localizing features suitable for the application of a physician’s or surgeon’s skills. On that day in a psychology laboratory, I learned that surgery based on these concepts was possible, and I knew that I had found my calling. I know that many neurosurgeons have had a similar meaningful experience.

In medical school, I began to work in a neuroscience laboratory in my spare time. At the end of my residency, I completed a fellowship in neuroanatomy. It was during this fellowship that I realized the potential for greater knowledge of microneurosurgery and microneurosurgical anatomy to improve the care of my patients. I resolved early in my career to incorporate this new technique into my practice, because it seemed to increase the safety with which we could delve deep into and under the brain. One of my favorite personal goals has been to find images of a single operation performed perfectly, because the inner discipline of striving toward perfection leads to improvement. Such images are the essential building blocks for the improvement of operative techniques. During my training and thereafter, I lay awake many nights, as I know all neurosurgeons have, worrying about a patient who was facing a necessary, critical, high-risk operation the next day. With the use of this new technique, I found that difficult operations that carried significant risk were performed with greater accuracy and less postoperative morbidity. During my training, I did not see a facial nerve preserved during the surgical removal of an acoustic neuroma. Today, that goal is accomplished in a high percentage of microsurgical procedures on acoustic neuromas. In the past, in operating on patients with pituitary tumors, there was minimal discussion of preserving the normal pituitary gland; today, however, the combination of new diagnostic and surgical techniques has made tumor removal with the preservation of normal pituitary function a frequent achievement. The application of microsurgery in neurosurgery has yielded a whole new level of neurosurgical performance and competence, and micro- surgical anatomy is the roadmap for applying microsurgical techniques.

As I began to work with microsurgical techniques, I realized that there was a need to train many neurosurgeons in their use. When I moved to the University of Florida, I began trying to develop a center for teaching neurosurgeons these techniques. Eventually, with the help of private contributions, my institution was able to purchase the necessary microscopes and equipment for a laboratory in which seven surgeons could learn at one time. The

next task was to find seven individuals who were willing to come to the university for a course. Finally, after much solicitation, seven surgeons joined us for a 1-week course. I was quite apprehensive about that course, because I was not sure that we could keep seven surgeons busy learning microvascular skills for a whole week. It was comforting to learn that Harvey Cushing, early in his career, had developed a similar laboratory in which surgeons could practice and perfect their operative skills. I still remember and am grateful to each member of the initial group of neurosurgeons who were willing to invest 1 week of their valuable time in our first course, more than 25 years ago. During the first afternoon of that course, I walked into the laboratory and, to my amazement, found seven surgeons working quietly and diligently. Nothing was said for long periods of time. In the midst of their intense endeavor and amazing quietness, I realized that we had tapped into a great force: the desire of neurosurgeons to improve themselves. Each individual neurosurgeon can acquire new skills so that a new level of performance in the specialty is achieved. Over the years, more than 1000 neurosurgeons have attended courses in our micro- neurosurgery laboratories. Microtechniques are now being applied throughout the specialty, thus adding a new level of delicacy and gentleness to neurosurgery. The competence of the whole specialty has been improved and with this experience has come the realization that neurosurgeons, as a group, are constantly aspiring to and achieving higher levels of performance that are not based on advances in diagnostic equipment and medication but are dependent on inspired individuals striving to improve their surgical skills to better serve their patients. Every year provides multiple examples of modifications in neurosurgery, based on the study and knowledge of microsurgical anatomy, that make operations more successful. It is amazing that, even after many years of study and practice, the insights gained from recent patients as well as continuing studies of microsurgical anatomy have lead to new and improved operative approaches. It is rewarding to see that most neurosurgery training programs now provide a laboratory for studying microsurgical anatomy and perfecting microsurgical techniques.

When we began our studies of anatomy more than 40 years ago, our dissections, even with microsurgical techniques, were crude by current standards. Photographs needed to be retouched to bring out the facets of anatomy important for achieving a satisfactory outcome at surgery. As we learned, over the years, to expose fine neural structures, the display of microsurgical anatomy became more vividly accurate and beautiful than we had imagined at the outset and has enhanced the accuracy and safety of our surgery. We hope that it will do the same for our readers.

Microsurgical anatomy will continue to be the science most fundamental to neurosurgery in the future. It will always occupy a major role in the training of neurosurgeons. The study and dissection of anatomic specimens improves

surgical skill. The study of microsurgical anatomy continues to be important in the improvement and adaptation of old techniques to new situations. Its study will lead to numerous new and more accurate operative approaches and the application of new neurosurgical technologies in future. Microsurgical anatomy provides the basis for understanding the constantly improving imaging studies and provides an understanding of the safest and most effective surgical pathway for visualizing and treating neurosurgical pathology. Every year, there are advances in neurological technology that yield new therapeutic possibilities that must be evaluated and directed according to an enhanced understanding of anatomy.

The combination of the knowledge of microsurgical anatomy and the use of the operating microscope have improved the technical performance of many standard neurosurgical procedures (e.g., brain, spine, and cranial base tumor removal; aneurysm obliteration; neurorrhaphy; and even lumbar and cervical discectomy) and has opened new dimensions that were previously unattainable. The knowledge of microsurgical anatomy has improved operative results by permitting neural and vascular structures to be approached and delineated with greater accuracy, deep areas to be reached by safer routes with less brain retraction and smaller cortical incisions, bleeding to be controlled with less damage to adjacent neural and vascular structures, and nerves and perforating arteries to be preserved with greater frequency. The use of the micro- scope, when combined with the knowledge of microsurgical anatomy, has resulted in smaller wounds, less postoperative neural and vascular damage, better hemostasis, more accurate nerve and vascular repairs, and surgical treatment for some previously inoperable lesions. The microscopic study of anatomy has introduced a whole new era in surgical education by permitting the recording of minute anatomic detail not visible to the eye for later study and discussion.

Surgery with the operating microscope has led the neurosurgeon to the current limits of human dexterity, but in the future, robotically assisted microsurgery will open new frontiers of delicate surgery that will require additional microanatomic detail for optimization. The evolution of other technologies, such as endovascular surgery, will continue to require an accurate knowledge of microsurgical anatomy. In the endovascular treatment of aneurysms, an understanding of the variations in the anatomy of the parent vessel and the perforating arteries is as important as it is to microsurgical treatment. Microsurgical anatomy provided the basis for our entry into cranial base surgery and gave us a road map for reaching every site in the cranial base through carefully placed windows. The joint development of microsurgery in combination with image guidance has made it possible to work in long, narrow exposures to reach multiple deep sites within the brain. The study of microsurgical anatomy has led to the development of new approaches, such as the transchoroidal approaches to the

third ventricle, the endonasal approach to pituitary tumor, and the telovelar approach to the fourth ventricle. In the future, there will be new, better, and safer procedures that will continue to evolve out of the continued study of microsurgical anatomy. It is hoped that the body of knowledge embodied in this volume will continue to be rele- vant to neurosurgical practice at the beginning of the next century and millennium.

Neurosurgery’s 25th Anniversary issue (4) on the supratentorial area with 1000 color illustrations and the Millennium issue (3) on the posterior fossa with nearly 800 illustrations represent a distillation of more than 40 years of work and study in which 65 residents and fellows have participated, resulting in several hundred publications. For those wanting even greater detail than displayed in this volume, our prior works, published largely in Neurosurgery and the Journal of Neurosurgery, can be consulted. In this volume, we have at- tempted not only to display the brain and cranial base in the best views for understanding the anatomy but also to show the anatomy as exposed in the surgical routes to the supratentorial and infratemporal areas and cranial base. Areas examined include the cerebrum, the cerebellum, the lateral, third, and fourth ventricles, the cranial nerves, the cranial base, the orbit, the cavernous sinus, the temporal bone, the cerebellopontine angle, the foramen magnum, and numerous other structures. Our work is not complete in any area. Further study will yield new information that will improve the operative approach and operative results in dealing with pathology in each of the areas previously examined. There is no “finish line” for this effort. Future anatomic study will continue to yield new insights throughout the future of our specialty. Insights gained from the other medical sciences and new technologies, when combined with our increasing knowledge of microsurgical anatomy, will create new surgical possibilities, therapies, and cures.

It has been gratifying to view the role of our fellows and trainees in spreading this knowledge to other countries around the world and to see the benefits of neurosurgeons applying this knowledge to improve their patients’ operations. Especially gratifying have been the relationships with Dr. Toshio Matsushima of Fukuoka, Japan, and Dr. Evandro de Oliveira of São Paulo, Brazil, whose studies of microsurgical anatomy have elevated the care of neurosurgical patients around the world. The following are the residents and fellows who have worked in the laboratory:

Hiroshi Abe, M.D., Japan

Hajime Arai, Japan

Allen S. Boyd, Jr., Tennessee

Robert Buza, Oregon

Alvaro Campero, Argentina

Alberto C. Cardoso, Brazil

Christopher C. Carver, California

Patrick Chaynes, France

Chanyoung Choi, Korea

Evandro de Oliveira, Brazil

Hatem El Khouly, Eg ypt

W. Frank Emmons, Washington

J. Paul Ferguson, Georgia

Andrew D. Fine, Florida

Brandon Fradd, Florida

Kiyotaka Fujii, Japan

Yutaka Fukushima, Japan

Adriano Scaff- Garcia, Brazil

Hirohiko Gibo, Japan

John L. Grant, Virginia

Kristinn Gudmundsson, Iceland

David G. Hardy, England

Frank S. Harris, Texas

Tsutomu Hitotsumatsu, Japan

Takuya Inoue, Japan

Tooru Inoue, Japan

Yukinari Kakizawa, Japan

Toshiro Katsuta, Japan

Masatou Kawashima, Japan

Chang Jin Kim, South Korea

Robert S. Knego, Florida

Shigeaki Kobayashi, Japan

Chae Heuck Lee, South Korea

Xiao-Yong Li, China

William Lineaweaver, California

J. Richard Lister, Illinois

Qing Liang Liu, China

Jack E. Maniscalco, Florida

Richard G. Martin, Alabama

Carolina Martins, Brazil

Haruo Matsuno, Japan

Toshio Matsushima, Japan

Juan C. Fernandez-Miranda, Spain

J. Robert Mozingo, deceased

Hiroshi Muratani, Japan

Antonio C.M. Mussi, Brazil

Shinji Nagata, Japan

Yoshihiro Natori, Japan

Kazunari Oka, Japan

Michio Ono, Japan

T. Glenn Pait, Arkansas

Wayne S. Paullus, Texas

David Perlmutter, Florida

Mark Renfro, Texas

Wade H. Renn, Georgia

Saran S. Rosner, New York

Pablo Rubino, Argentina

Naokatsu Saeki, Japan

Shuji Sakata, Japan

Eduardo R. Seoane, Argentina

Xiang-en Shi, China

Satoru Shimizu, Japan

Ryusui Tanaka, Japan

Necmettin Tanriover, Turkey

Helder Tedeschi, Brazil

Erdener Timurkaynak, Turkey

Xiaoguang Tong, China

Satoshi Tsutsumi, Japan

Arthur J. Ulm, Florida

Hung T. Wen, Brazil

C.J. Whang, South Korea

Isao Yamamoto, Japan

Alexandre Yasuda, Brazil

Nobutaka Yoshioka, Japan

Arnold A. Zeal, Florida

Special thanks go to our medical illustrators, David Peace and Robin Barry, who have worked with us for more than 2 decades. David and Robin’s illustrations have graced surgical publications, including the covers of Neurosurgery and the Journal of Neurosurgery, for decades. I also extend special thanks to Ron Smith who has directed the microsurgery laboratory for many years, and to Laura Dickinson and Fran Johnson, who have labored over these and earlier manuscripts.

This work has been sustained by numerous private contributions to our department and the University of Florida. Most prominent among these has been that of the R.D. Keene family, who made the first $1 million gift to the University of Florida, a gift that has supported our work for many years. That gift was followed by additional endowments that have grown to nearly $20 million, which support many aspects of education and research in neurosurgery and the neurosciences at the University of Florida. These gifts have endowed the following chairs and professorships:

The R.D. Keene Family Chair

The C.M. and K.E. Overstreet Chair The Mark Overstreet Chair

The Albert E. and Birdie W. Einstein Chair The James and Newton Eblen Chair

The Dunspaugh-Dalton Chair

The Edward Shed Wells Chair

The Robert Z. and Nancy J. Greene Chair The L.D. Hupp Chair

The William Merz Professorship

The Albert L. Rhoton, Jr. Chairman’s Professorship

The most recent of these is the series of gifts and matching funds totaling nearly $5 million establishing the Albert L. Rhoton, Jr. Neurosurgery Professorship held by William A. Friedman, who followed me as chair of the Department of Neurosurgery. The efforts of the numerous clinicians and scientists recruited, as a result of the Endowed Chairs, contributed greatly to the founding the Evelyn F. and William L. McKnight Brain Institute of the University of

Florida, where our studies of microsurgical anatomy are being completed. With this volume, we join our donors in their aspiration to improve the life of patients who undergo brain surgery throughout the world.

Before closing, I would like to thank my wife, Joyce, who has allowed microsurgical anatomy to become a hobby that has consumed much of my time away from the medical center. It is to Joyce that this volume is dedicated. In closing, I would also like to thank Editor Michael Apuzzo, not only from the bottom of my heart, but from the depths of my most valuable earthly possession, my brain, for allowing me to complete this work.

REFERENCES

1. Rhoton AL Jr: Presidential Address: Improving ourselves and our specialty. Clin Neurosurg 26:xiii–xix , 1979.

2. Rhoton AL Jr: Neurosurgery in the Decade of the Brain: The 1990 Presidential Address. J Neurosurg 73:487–495, 1990.

3. Rhoton AL Jr: The posterior cranial fossa: Microsurgical anatomy & surgical approaches. Neurosurgery 47[Suppl 1]:S1–S298, 2000.

4. Rhoton AL Jr: The supratentorial cranial space: Microsurgical anatomy and surgical approaches. Neurosurgery 51[Suppl 1]:S1-1–S1-410, 2002.

Albert L. Rhoton, Jr. 1932–2016 Gainesville, Florida

PART 1

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUES & INSTRUMENTATIONFOR NEUROSURGERY

AlbertL.Rhoton,Jr.,M.D. DepartmentofNeurological Surgery,UniversityofFlorida,

Gainesville,Florida

Reprintrequests:

AlbertL.Rhoton,Jr.,M.D., DepartmentofNeurological Surgery,UniversityofFlorida McKnightBrainInstitute,P.O.Box 100265,Gainesville,FL 32610-0265.

Email:rhoton@neurosurgery.ufl.edu

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUESAND INSTRUMENTATIONFOR NEUROSURGERY

KEYWORDS: Cranialsurgery,Craniotomy,Instrumentation,Microneurosurgery,Microsurgery,Operative techniques,Surgicalinstruments,Surgicalmicroscope

Theintroductionoftheoperatingmicroscopeforneurosurgerybroughtaboutthe greatestimprovementsinoperativetechniquesthathaveoccurred inthehistoryofthespecialty.The microscopehasresultedinprofoundchangesintheselectionand useofinstrumentsandinthewayneurosurgicaloperationsare completed.Theadvantagesprovidedbytheoperatingmicroscope inneurosurgerywerefirstdemonstratedduringtheremovalof acousticneuromas(4).Thebenefitsofmagnifiedstereoscopicvision andintenseilluminationprovidedbythemicroscopewerequickly realizedinotherneurosurgicalprocedures.Theoperatingmicroscopeisnowusedfortheintraduralportionofnearlyalloperations involvingtheheadandspineandformostextraduraloperations involvingthespineandcranialbase,convertingalmostallofneurosurgeryintoamicrosurgicalspecialty.

Microsurgeryhasimprovedthetechnicalperformanceofmany standardneurosurgicalprocedures(e.g.,braintumorremoval,aneurysmobliteration,neurorrhaphy,andlumbarandcervicaldiscectomy)andhasopenednew,previouslyunattainableareastothe neurosurgeon.Ithasimprovedoperativeresultsbypermittingneuralandvascularstructurestobedelineatedwithgreatervisual accuracy,deepareastobereachedwithlessbrainretractionand smallercorticalincisions,bleedingpointstobecoagulatedwithless damagetoadjacentneuralstructures,nervesdistortedbytumorto bepreservedwithgreaterfrequency,andanastomosisandsuturing ofsmallvesselsandnervesnotpreviouslypossibletobeperformed. Itsusehasresultedinsmallerwounds,lesspostoperativeneural andvasculardamage,betterhemostasis,moreaccuratenerveand vesselrepairs,andsurgicaltreatmentofsomepreviouslyinoperable lesions.Ithasintroducedanewerainsurgicaleducation,bypermittingtheobservationandrecording(forlaterstudyanddiscussion)ofminuteoperativedetailsnotvisibletothenakedeye.Some generalconsiderationsarereviewedbeforediscussionofinstrument selectionandoperativetechniques.

GENERALCONSIDERATIONS

Achievingasatisfactoryoperativeresultdependsnotonly onthesurgeon’stechnicalskillanddexteritybutalsoonahost

ofdetailsrelatedtoaccuratediagnosisandcarefulpreoperativeplanning.Essentialtothisplanishavingapatientand familymemberswhoarewellinformedaboutthecontemplatedoperationandwhounderstandtheassociatedside effectsandrisks.Thesurgeon’smostimportantallyinachievingasatisfactorypostoperativeresultisawell-informed patient.

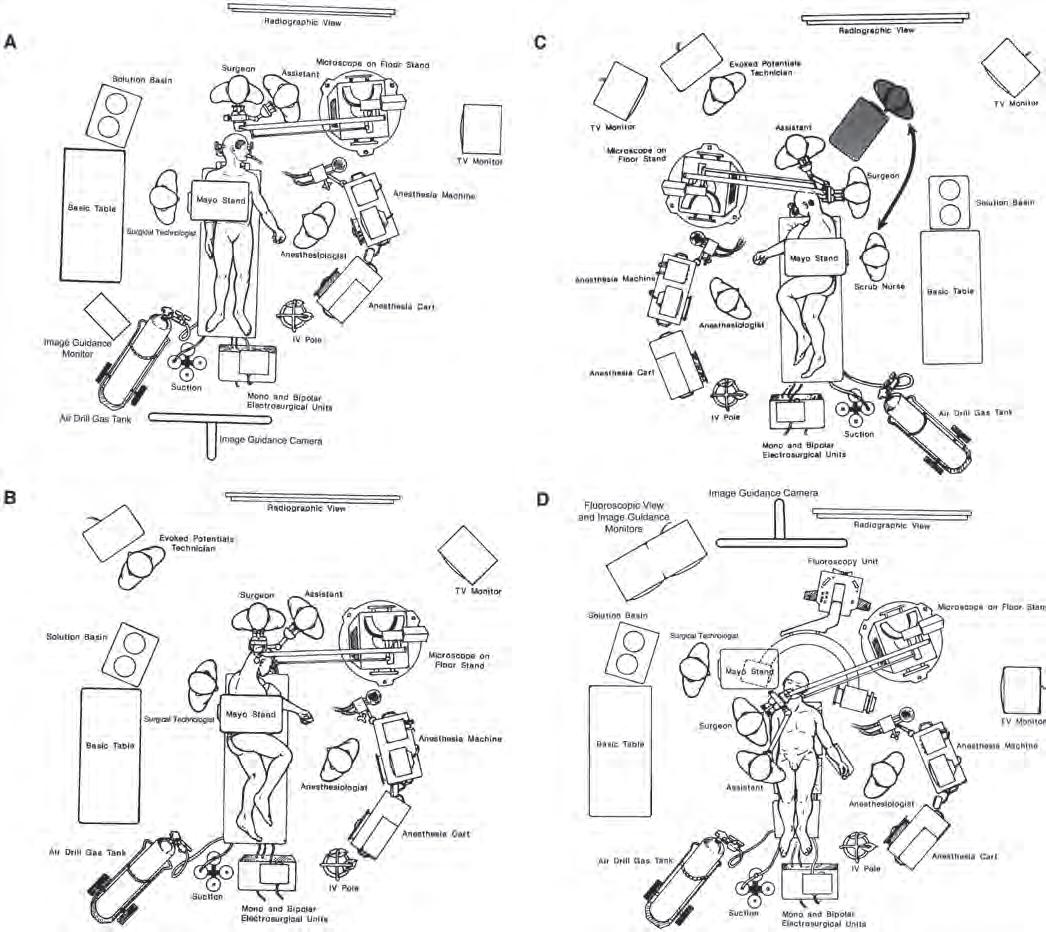

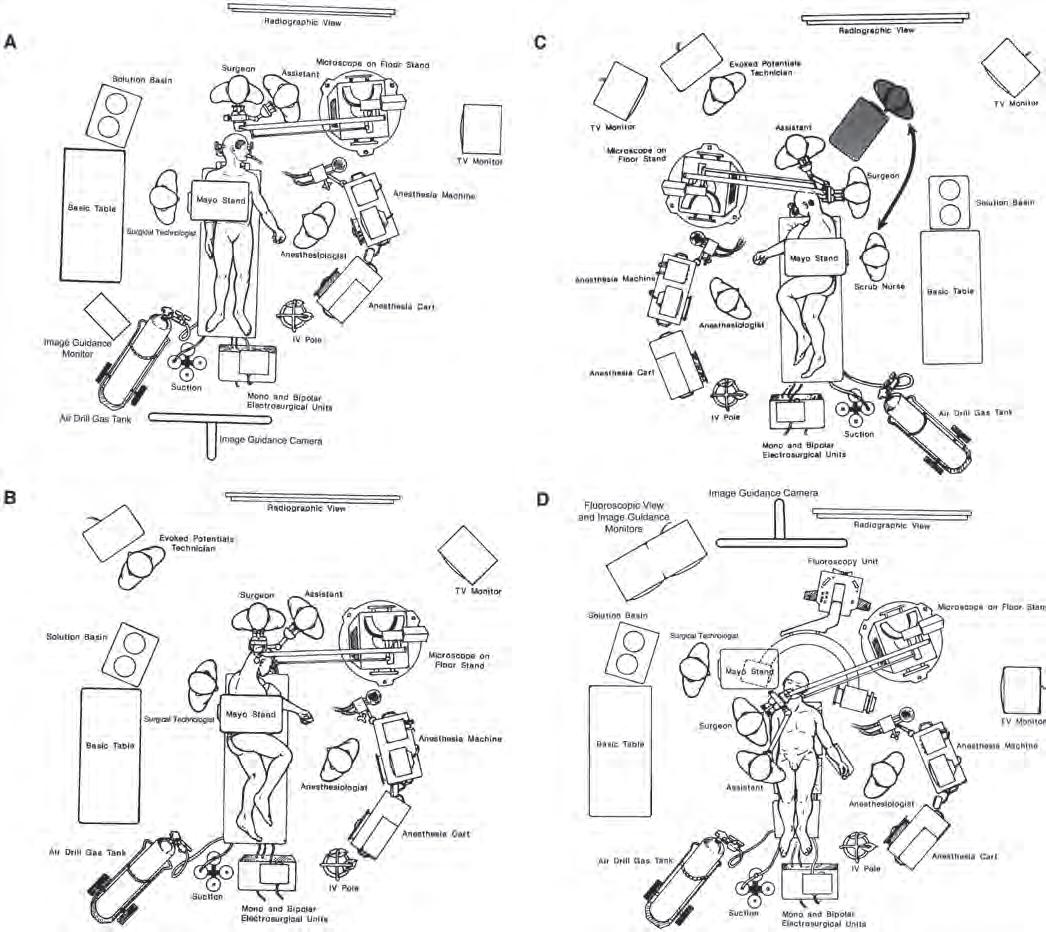

Operatingroomschedulingshouldincludeinformationon thesideandsiteofthepathologicallesionandthepositionof thepatient,sothattheinstrumentsandequipmentcanbe properlypositionedbeforethearrivalofthepatient(Fig.1.1). Anyunusualequipmentrequiredshouldbelistedatthetime ofscheduling.Therearedefiniteadvantagestohavingoperatingroomsdedicatedtoneurosurgeryandtoschedulingthe samenurses,whoknowtheequipmentandprocedures,forall neurosurgicalcases.

Beforeinduction,thereshouldbeanunderstandingbetweenthesurgeonandanesthesiologistregardingtheneedfor administrationofcorticosteroids,hyperosmoticagents,anticonvulsants,antibiotics,andbarbiturates,lumbarorventriculardrainage,andintraoperativeevokedpotential,electroencephalographic,orotherspecializedmonitoring.Elasticor pneumaticstockingsareplacedonthepatient’slowerextremities,topreventvenousstagnationandpostoperativephlebitis andemboli.Aurinarycatheterisinsertediftheoperationis expectedtolastmorethan2hours.Ifthepatientispositioned sothattheoperativesiteissignificantlyhigherthantheright atrium,thenaDopplermonitorisattachedtothechestor insertedintotheesophagusandavenouscatheterispassed intotherightatrium,sothatvenousairembolicanbedetected andtreated.Atleasttwointravenouslinesareestablishedif significantbleedingislikelytooccur.

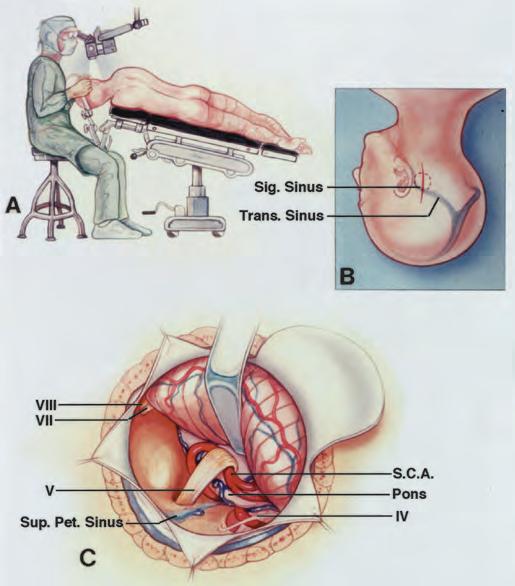

Mostintracranialproceduresareperformedwiththepatientin thesupine,three-quarterprone(lateralobliqueorpark-bench), orfullyproneposition,withthesurgeonsittingattheheadofthe table(Fig.1.1).Thesupineposition,withappropriateturningofthe patient’sheadandneckandpossiblyelevationofoneshoulderto rotatetheuppertorso,isselectedforproceduresinthefrontal, temporal,andanteriorparietalareasandformanycranialbase approaches.The three-quarterproneposition,withthetable tiltedtoelevatethehead,isusedforexposureoftheposterior parietal, occipital,andsuboccipitalareas(Figs.1.1–1.3).Somesur-

FIGURE1.1. Positioningofstaffandequipmentintheoperatingroom. A,positioningforarightfrontotemporalcraniotomy.Theanesthesiologistispositionedon thepatient’sleftside,wherethephysiciancanhaveeasyaccesstotheairway,monitorsonthechest,andtheintravenous(IV)andintra-arteriallines.Themicroscope standispositionedabovetheanesthesiologist.Thescrubnurse,positionedontherightsideofthepatient,passesinstrumentstothesurgeon’srighthand.Theposition isreversedforaleftfrontotemporalcraniotomy,withtheanesthesiologistandmicroscopeonthepatient’srightsideandthenurseontheleftside.Mayostandshave replacedthelargeheavyinstrumenttablespositionedabovethepatient’strunk,whichrestrictedaccesstothepatient.Thesuctionsystem,compressedairtanksforthe drill,andelectrosurgeryunitsarepositionedatthefootofthepatient;thelinesfromtheseunitsareledupneartheMayostand,sothatthenursecanpassthemto thesurgeonasneeded.Atelevision(TV)monitorispositionedsothatthenursecananticipatetheinstrumentneedsofthesurgeon.Theinfraredimageguidancecamera ispositionedsothatthesurgeon,assistants,andequipmentdonotblockthecamera’sviewofthemarkersattheoperativesite. B,positioningforarightsuboccipital craniotomydirectedtotheupperpartoftheposteriorfossa,suchasadecompressionoperationfortreatmentoftrigeminalneuralgia.Thesurgeonisseatedatthehead ofthepatient.Theanesthesiologistandmicroscopearepositionedonthesidethepatientfaces.Theanesthesiologistandnurseshiftsidesforanoperationontheleft side. C,positioningforaleftsuboccipitalcraniotomyforremovalofanacousticneuroma.Thesurgeonisseatedbehindtheheadofthepatient.Forremovalofaleft acoustictumor,thescrubnurse,withtheMayostand,maymoveuptothe shadedarea,whereinstrumentscanbepassedtothesurgeon’srighthand.Forright suboccipitaloperationsorformidlineexposures,thepositionsarereversed,withthescrubnurseandMayostandbeingpositionedabovethebodyofthepatient,which allowsthenursetopassinstrumentstothesurgeon’srighthand.Ineachcase,theanesthesiologistispositionedonthesidetowardwhichthepatientfaces. D,positioning fortranssphenoidalsurgery.Thesurgeonispositionedontherightsideofthepatientandtheanesthesiologistontheleftside.Thepatient’sheadisrotatedslightlyto therightandtiltedtotheleft,toprovidethesurgeonwithaviewdirectlyupthepatient’snose.ThemicroscopestandislocatedjustoutsidetheC-armonthefluoroscopy unit.ThenurseandMayostandarepositionednearthepatient’shead,aboveonearmofthefluoroscopyunit.Theimageguidancecameraispositionedsothatthe surgeondoesnotblockitsviewoftheoperativesite.

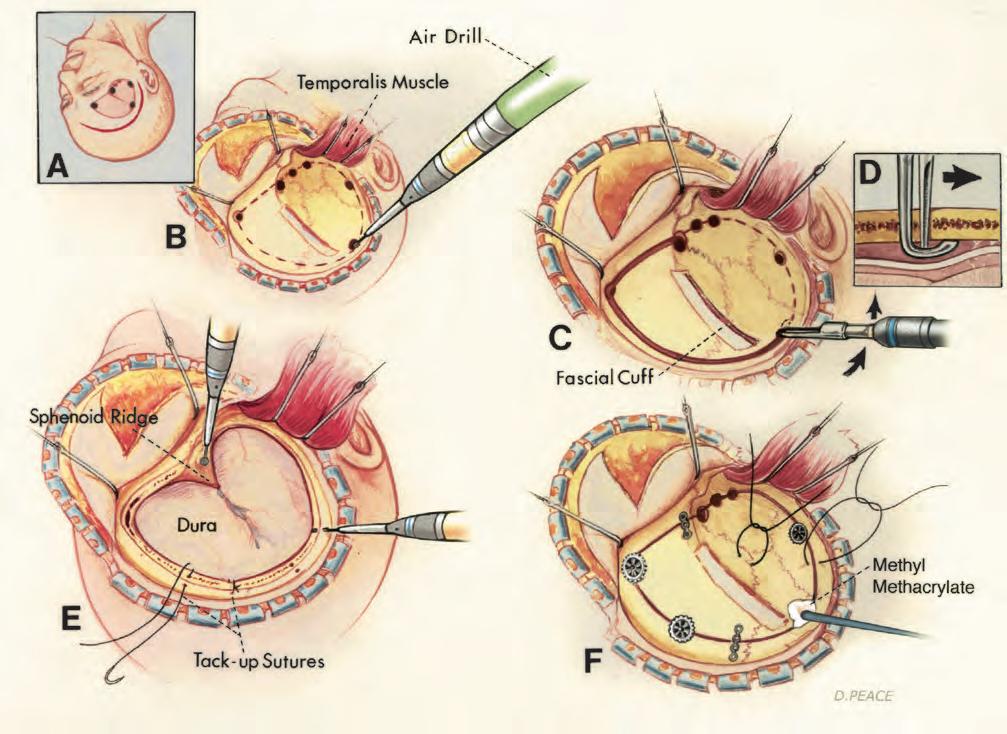

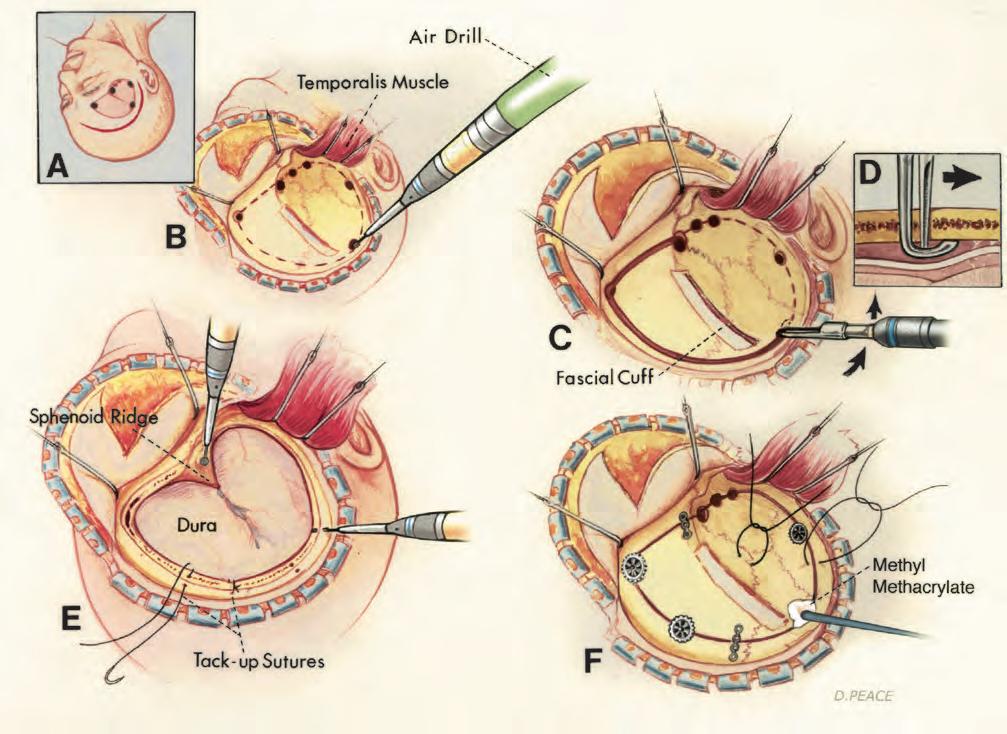

FIGURE1.2. Techniqueforcraniotomyusingahigh-speedairorelectricdrill. A,rightfrontotemporalscalpandfreeboneflapsareoutlined. B,thescalpflaphasbeen reflectedforwardandthetemporalismuscledownward.Elevationofthetemporalismusclewithcarefulsubperiostealdissectionwithaperiostealelevator,ratherthan thecuttingBovieelectrocautery,facilitatespreservationofthemuscle’sneuralandvascularsupplies,whichcourseintheperiostealattachmentsofthemuscletothe bone.Thehigh-speeddrillpreparesburrholesalongthemarginsoftheboneflap(dashedline). C,anarrowtool,withafootplatetoprotectthedura,connectsthe holes. D,acrosssectionalviewofthecuttingtoolindicateshowthefootplatestripstheduraawayfromthebone. E,thehigh-speeddrillremovesthelateralpartof thesphenoidridge.Adrillbitmakesholesintheboneedgefortack-upsuturestoholdtheduraagainstthebonymargin. F,aftercompletionoftheintraduralpartof theoperation,theboneflapisheldinplacewithplatesandscrewsorburrholecoversthataligntheinnerandoutertablesoftheboneflapandadjacentcranium.Silk suturesbroughtthroughdrillholesinthemarginoftheboneflapmaybeusedbutdonotpreventinwardsettlingoftheboneflaptothedegreeachievedwithplating. Somemethylmethacrylatemaybemoldedintosomeburrholesorotheropeningsinthebone,toprovidefirmcosmeticclosure.

geons stillprefertohavethepatientinthesemi-sittingposition foroperationsinvolvingtheposteriorfossaandcervicalregion, becausetheimprovedvenousdrainagemayreducebleedingand becausecerebrospinalfluidandblooddonotcollectinthedepth oftheexposure.Tiltingthewholetabletoelevatetheheadofthe patientinthelateralobliquepositionalsoreducesvenousengorgementattheoperativesite.Extremesofturningofthehead andneck,whichmayleadtoobstructionofvenousdrainage fromthehead,shouldbeavoided.Pointsofpressureortraction onthepatient’sbodyshouldbeexaminedandprotected.

Carefulattentiontothepositioningofoperatingroompersonnelandequipmentensuresgreaterefficiencyandeffectiveness. Theanesthesiologistispositionedneartheheadandchestonthe sidetowardwhichtheheadisturned,witheasyaccesstothe endotrachealtubeandtheintravenousandintra-arteriallines,

ratherthanatthefootofthepatient,whereaccesstosupport systemsislimited(Fig.1.1).Ifthepatientistreatedinthesupine orthree-quarterproneposition,thentheanesthesiologistispositionedonthesidetowardwhichthefaceisturnedandthe scrubnurseispositionedontheotherside,withthesurgeon seatedattheheadofthepatient(e.g.,foraleftfrontalorfrontotemporalapproach,theanesthesiologistispositionedonthe patient’srightsideandthescrubnurseisontheleftside).

Greatereaseinpositioningtheoperatingteamaroundthe patientisobtainedwheninstrumentsareplacedonMayostands, whichcanbemovedaroundthepatient.Inthepast,large,heavy, overheadstandswithmanyinstrumentswerepositionedabove thebodyofthepatient.TheuseofMayostands,whicharelighter andmoreeasilymoved,allowsthescrubnurseandtheinstrumentstobepositionedandrepositionedattheoptimalsiteto

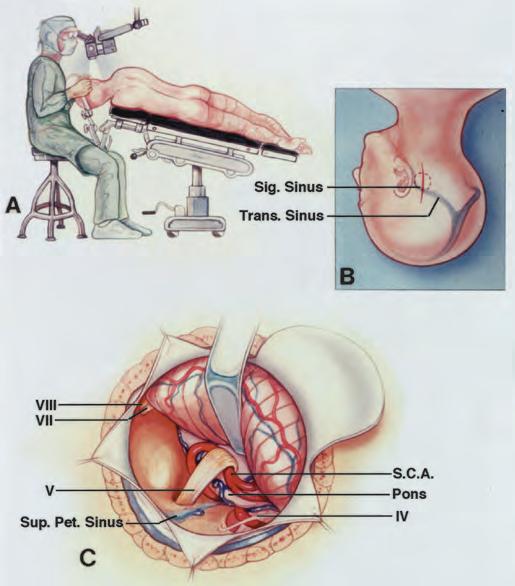

FIGURE1.3. Retrosigmoidapproachtothetrigeminalnerveforadecompression operation. A,thepatientispositionedinthethree-quarterproneposition.The surgeonisattheheadofthetable.Thepatient’sheadisfixedinapinionheadholder. Thetableistiltedtoelevatethehead. B,theverticalparamediansuboccipitalincision crossestheasterion.Asmallcraniotomyflap,ratherthanacraniectomy,isusedfor approachestothecerebellopontineangle.Thesuperolateralmarginofthecraniotomy ispositionedatthelower-edgejunctionofthetransverseandsigmoidsinuses. C,the superolateralmarginofthecerebellumisgentlyelevatedwithataperedbrainspatula, toexposethesiteatwhichthesuperiorcerebellararteryloopsdownintotheaxillaof thetrigeminalnerve.Thebrainspatulaisadvancedparalleltothesuperiorpetrosal sinus.Thetrochlear,facial,andvestibulocochlearnervesareintheexposure.Thedura alongthelateralmarginoftheexposureistackeduptotheadjacentmuscles,to maximizetheexposure.Attheendoftheprocedure,theboneflapisheldinplacewith magneticresonanceimaging-compatibleplates. Pet.,petrosal; S.C.A.,superiorcerebellarartery; Sig.,sigmoid; Sup.,superior; Trans.,transverse(from,RhotonALJr: Microsurgicalanatomyofdecompressionoperationsonthetrigeminalnerve,in RovitRL(ed): TrigeminalNeuralgia.Baltimore,Williams&Wilkins,1990,pp 165–200[9]).

assistthesurgeon.Italsoprovidestheflexibilitydemandedby themorefrequentuseofintraoperativefluoroscopy,imageguidance,andangiography.Thecontrolconsolefordrills,suction, andcoagulationisusuallypositionedatthefootoftheoperating table,andthetubesandlinesareledupwardtotheoperativesite.

Inthepast,itwascommontoshavetheentireheadformost intracranialoperations,buthairremovalnowcommonlyextendsonly1.5to2cmbeyondthemarginoftheincision,with carebeingtakentoshaveanddrapeawideenoughareato allowextensionoftheincisionifalargeroperativefieldis neededandtoallowdrainstobeledoutthroughstabwounds. Somesurgeonscurrentlydonotremovehairinpreparation forascalpincisionandcraniotomy.Forsupratentorialoper-

ations,itmaybehelpfultooutlineseveralimportantlandmarksonthescalp beforethedrapesareapplied.Sitescommonly markedincludethecoronal,sagittal,andlambdoidsutures,the rolandicandsylvianfissures,andthepterion,inion,asterion,and keyhole(Fig.1.4).

Scalpflapsshouldhaveabroadbaseandadequateblood supply(Fig.1.2).Apediclethatisnarrowerthanthewidthof theflapmayresultintheflapedgesbecominggangrenous.An effortismadetopositionscalpincisionssothattheyare behindthehairlineandnotontheexposedpartoftheforehead.Abicoronalincisionlocatedbehindthehairlineispreferabletoextensionofanincisionlowontheforeheadfora unilateralfrontalcraniotomy.Anattemptismadetoavoidthe branchofthefacialnervethatpassesacrossthezygomato reachthefrontalismuscle.Incisionsreachingthezygoma morethan1.5cmanteriortotheearcommonlyinterruptthis nerveunlessthelayersofthescalpinwhichitcoursesare protected([14],see Fig.6.9).Thesuperficialtemporaland occipitalarteriesshouldbepreservedifthereisthepossibility thattheywillbeneededforanextracranial-intracranialarterialanastomosis.

Duringelevationofascalpflap,thepressureofthesurgeon’sandassistant’sfingersagainsttheskinoneachsideof theincisionisusuallysufficienttocontrolbleedinguntilhemostaticclipsorclampsareapplied.Theskinisusuallyincisedwithasharpblade,butthedeeperfascialandmuscle layersmaybeincisedwithacuttingBovieelectrocautery.The groundplateontheelectrocuttingunitshouldhaveabroad baseofcontact,topreventtheskinatthegroundplatefrom beingburned.Achievingasatisfactorycosmeticresultwitha supratentorialcraniotomyoftendependsonpreservationof thebulkandviabilityofthetemporalismuscle.Thisisbest achievedbyavoidingtheuseofthecuttingBovieelectrocauteryduringelevationofthemusclefromthebone.Boththe vascularandneuralsuppliesofthetemporalismusclecourse tightlyalongthefascialattachmentsofthemuscletothebone, wheretheycouldeasilybedamagedwithahotcuttinginstrument([14],see Fig.6.9).Optimalpreservationofthemuscle’s bulkisbestachievedbyseparationofthemusclefromthe boneviaaccuratedissectionwithasharpperiostealelevator. Bipolarcoagulationisroutinelyusedtocontrolbleeding fromthescalpmargins,onthedura,andatintracranialsites. Atsiteswhereevengentlebipolarcoagulationcouldresultin neuraldamage,suchasaroundthefacialoropticnerves,an attemptismadetocontrolbleedingwithagentlyapplied hemostaticgelatinoussponge(Gelfoam;UpjohnCo.,Kalamazoo,MI).Alternativestogelatinousspongesincludeoxidized regeneratedcellulose(Surgicel;Surigkos,NewBrunswick, NJ),oxidizedcellulose(Oxycell;ParkeDavis,MorrisPlains, NJ),andmicrofibrillarcollagenhemostats(Avitene;Avicon, Inc.,FortWorth,TX).Venousbleedingcanoftenbecontrolled withthelightapplicationofgelatinoussponges.Metallicclips, whichwere oftenusedontheduraandvesselsinthepast,arenow appliedinfrequentlyexceptonaneurysmnecks,becausetheyinterferewiththequalityofcomputedtomographicscans;iftheyare used,theyshouldbecomposedofnonmagneticalloysortitanium. UseofaseriesofburrholesmadewithamanualormotordriventrephineconnectedtoaGiglisawforelevatingbone

FIGURE1.4. Sitescommonlymarked onthescalpbeforeapplicationofthe drapes,includingthecoronal,sagittal, andlambdoidsutures,therolandicand sylvianfissures,andthepterion,inion, asterion,andkeyhole.Approximationof thesitesofthesylvianandrolandicfissuresonthescalpbeginswithobservation ofthepositionsofthenasion,inion,and frontozygomaticpoint.Thenasionislocatedinthemidline,atthejunctionofthe nasalandfrontalbones.Theinionisthe siteofabonyprominencethatoverliesthe torcula.Thefrontozygomaticpointislocatedontheorbitalrim,2.5cmabovethe levelatwhichtheupperedgeofthezygomaticarchjoinstheorbitalrimandjust belowthejunctionofthelateralandsuperiormarginsoftheorbitalrim.Thenext stepsaretoconstructalinealongthe sagittalsutureand,withaflexiblemeasuringtape,todeterminethedistance alongthislinefromthenasiontotheinion andtomarkthemidpointandthreequarterpoint(50and75%points,respectively).Thesylvianfissureislocated alongalinethatextendsbackwardfrom thefrontozygomaticpoint,acrossthelateralsurfaceofthehead,tothethree-quarterpoint.Thepterion,i.e.,thesiteonthetempleapproximatingthelateralendofthe sphenoidridge,islocated3cmbehindthefrontozygomaticpoint,onthesylvianfissureline.Therolandicfissureislocatedbyidentifyingtheupperandlowerrolandic points.Theupperrolandicpointislocated2cmbehindthemidpoint(50%plus2cmpoint),onthenasion-to-inionmidsagittalline.Thelowerrolandicpointislocated wherealineextendingfromthemidpointoftheuppermarginofthezygomaticarchtotheupperrolandicpointcrossesthelinedefiningthesylvianfissure.Aline connectingtheupperandlowerrolandicpointsapproximatestherolandicfissure.Thelowerrolandicpointislocatedapproximately2.5cmbehindthepterion,onthe sylvianfissureline.Anotherimportantpointisthekeyhole,thesiteofaburrholethat,ifproperlyplaced,hasthefrontaldurainthedepthsofitsupperhalfandthe periorbitainitslowerhalf.Itisapproximately3cmanteriortothepterion,justabovethelateralendofthesuperiororbitalrimandunderthemostanteriorpointof attachmentofthetemporalismuscleandfasciatothetemporalline(from,RhotonALJr:Thecerebrum. Neurosurgery 51[Suppl1]:S1-1–S1-51,2002[15]).

flapshasgivenwaytotheuseofhigh-speeddrillsformaking burrholesandcuttingthemarginsofboneflaps(Fig.1.2). Commonly,aholeispreparedbyusingacuttingburrona high-speeddrillandatoolwithafootplate,toprotectthe duralcutsaroundthemarginsoftheflap.Extremelylong bonecutsshouldbeavoided,especiallyiftheyextendacross aninternalbonyprominence,suchasthepterion,oracrossa majorvenoussinus.Theriskoftearingtheduraorinjuringthe brainisreducedbydrillingseveralholesandmakingshorter cuts.Aholeisplacedoneachsideofavenoussinusandthe duraiscarefullystrippedfromthebone,afterwhichthebone cutiscompleted,ratherthanthebonebeingcutabovethe sinusaspartofalongcutaroundthewholemarginoftheflap. Bleedingfromboneedgesisstoppedwiththeapplicationof bonewax.Bonewaxisalsousedtoclosesmallopeningsinto themastoidaircellsandothersinuses,butlargeropeningsin thesinusesareclosedwithothermaterials,suchasfat,muscle, orpericranialgrafts,sometimesinconjunctionwithathin plateofmethylmethacrylateorotherbonesubstitute.

Afterelevationoftheboneflap,itiscommonpracticeto tacktheduratothebonymarginwithafew3-0blacksilk suturesbroughtthroughtheduraandthenthroughsmalldrill holesinthemarginofthecranialopening(Fig.1.2).Ifthebone flapislarge,thentheduraisalso “snuggedup” totheintracranialsideoftheboneflapwiththeuseofasuturebrought

throughdrillholesinthecentralpartoftheflap.Careistaken toavoidplacingdrillholesfortack-upsuturesthatmight extendintothefrontalsinusormastoidaircells.Tack-up suturesaremorecommonlyusedforduraoverthecerebral hemispheresthanforduraoverthecerebellum.Ifthebrainis pressedtightlyagainstthedura,thenthetack-upsuturesare placedaftertreatmentoftheintraduralpathologicallesion, whenthebrainisrelaxedandthesuturescanbeplacedwith directobservationofthedeepsurfaceofthedura.Tack-up suturescanalsobeledthroughadjacentmusclesorpericranium,ratherthanaholeinthemarginoftheboneflap.

Inthepast,therewasatendencyforboneflapstobe elevatedandreplacedoverthecerebralhemispheresandfor exposuresinthesuboccipitalregiontobeperformedascraniectomies,withoutreplacementofthebone.Laterallyplaced suboccipitalexposuresarenowcommonlyperformedas craniotomies,withreplacementoftheboneflaps.Midline suboccipitaloperationsaremorecommonlyperformedas craniectomies,especiallyifdecompressionattheforamen magnumisneeded,becausethisareaisprotectedbyagreater thicknessofoverlyingmuscles.

Boneflapsareusuallyheldinplacewithnonmagnetic platesandscrewsorsmallmetaldiscsorburrholecoversthat compressandaligntheinnerandoutertablesoftheboneflap andtheadjacentcranium(Fig.1.2F).Remainingdefectsinthe

bonearecommonlycoveredwithmetaldiscsorfilledwith methylmethacrylate,whichisallowedtohardeninplacebeforethescalpisclosed.

Theduraisclosedwith3-0silkinterruptedorrunning sutures.Smallbitsoffatormusclemaybesuturedoversmall openingscausedbyshrinkageofthedura.Largerduraldefectsareclosedwithpericraniumortemporalisfasciaobtained fromtheoperativesite,withsterilizedcadavericduraorfascia lata,orwithotherapprovedduralsubstitutes.Thedeepmusclesandfasciaarecommonlyclosedwith1-0,thetemporalis muscleandfasciawith2-0,andthegaleawith3-0synthetic absorbablesutures.Thescalpisusuallyclosedwithmetallic staples,exceptatsiteswheresome3-0or5-0nylonreenforcing suturesmaybeneeded.Skinstaplesareassociatedwithless tissuereactionthanareotherformsofclosurewithsutures.

HEADFIXATIONDEVICES

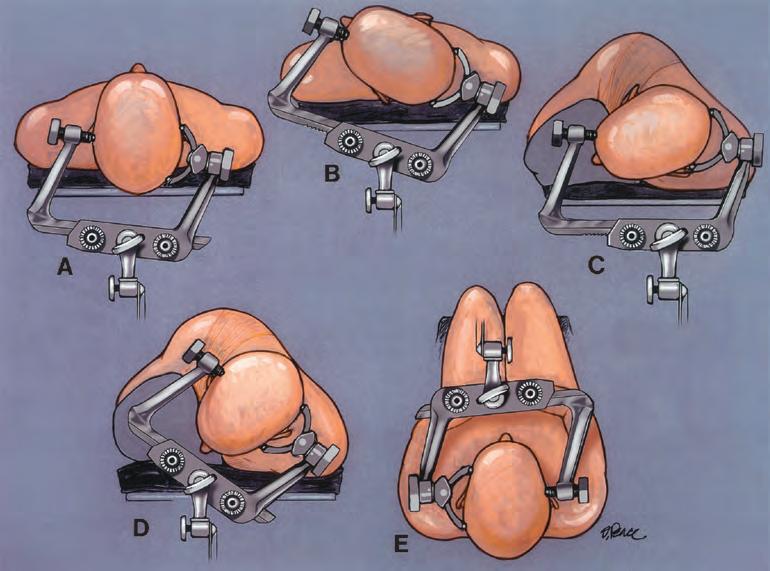

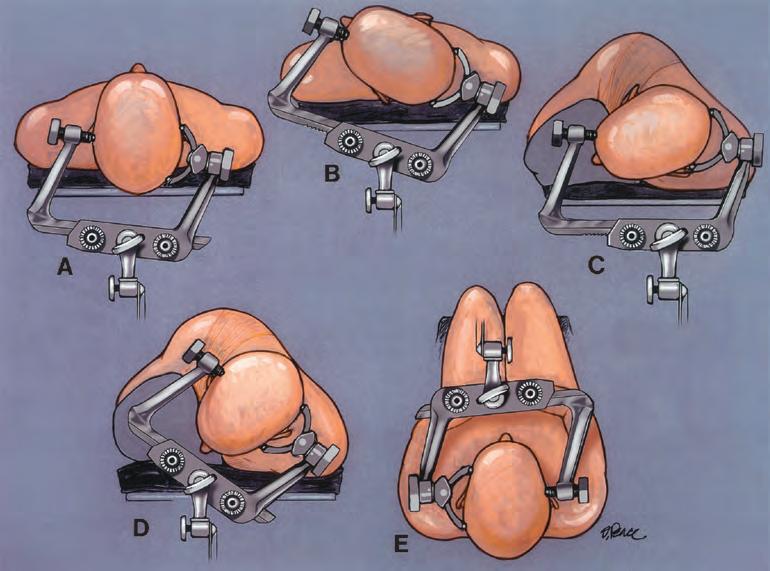

Precisemaintenanceofthefirmlyfixedcraniumintheoptimal positiongreatlyfacilitatestheoperativeexposure(Figs.1.5 and 1.6).Fixationisbestachievedwithapinionheadholder,inwhich theessentialelementisaclampmadetoaccommodatethree relativelysharppins.Whenthepinsareplaced,careshouldbe takentoavoidaspinalfluidshunt,thinbones(suchasthosethat overliethefrontalandmastoidsinuses),andthethicktemporalis muscle(wheretheclamp,howevertightlyapplied,tendsto remainunstable).Thepinsshouldbeappliedwellawayfromthe eyeandareaswheretheywouldhindertheincision.Shorter pediatricpinsareavailableforthincrania.Thepinsshouldnotbe placedoverthethincraniaofsomepatientswithahistoryof hydrocephalus.Aftertheclamphasbeensecuredonthehead,

FIGURE1.5. Positioningofapinion headholderforacraniotomy.Threepins penetratethescalpandarefirmlyfixedto theoutertableofthecranium. A,position oftheheadholderforaunilateralorbilateralfrontalapproach. B,positionfora pterionalorfrontotemporalcraniotomy. C,positionforaretrosigmoidapproachto thecerebellopontineangle. D,positionfor amidlinesuboccipitalapproach. E,positionforamidlinesuboccipitalapproach withthepatientinthesemi-sittingposition.Thepinsarepositionedtoavoidthe thinboneoverthefrontalsinusandmastoidaircellsandthetemporalismuscle. Thesidearmsoftheheadclampshouldbe shapedtoaccommodatetheC-clamps holdingtheretractorsystem.Thepinion headholderhasaboltthatresemblesa sunburst,forattachmenttotheoperating table.Placementofthreesunburstsiteson theheadclamp,ratherthanonlyone,allowsgreaterflexibilityinattachingthe headclamptotheoperatingtableandprovidesextrasitesfortheattachmentofretractorsystemsandinstrumentsforinstrumentguidance.

thefinalpositioningiscompletedandtheheadholderisfixedto theoperatingtable.

Thistypeofimmobilizationallowsintraoperativerepositioningofthehead.Theclampavoidstheskindamagethatmay occurifthefacerestsagainstapaddedheadsupportforseveral hours.Thecranialclampsdonotobscurethefaceduringthe operation(asdopaddedheadrests),facilitatingintraoperative electromyographicmonitoringofthefacialmusclesandmonitoringofauditoryorsomatosensoryevokedpotentials.Until recently,allheadclampswereconstructedfromradiopaque metals,buttheincreasinguseofintraoperativefluoroscopyand angiographyhaspromptedthedevelopmentofheadholders constructedfromradiolucentmaterials.Thepinionheadholder commonlyservesasthesiteofattachmentofthebrainretractor system.Thesidearmsoftheheadclampshouldbeshapedto accommodatetheC-clampssecuringtheretractorsystem.The pinionheadholderhasaboltthatresemblesasunburst,for attachmenttotheoperatingtable.Placementofthreesunburst sitesontheheadclamp,ratherthanonlyone,allowsgreater flexibilityinattachmentoftheheadclamptotheoperatingtable andprovidesextrasitesfortheattachmentofretractorsystems andcomponentsoftheimageguidancesystem.

INSTRUMENTSELECTION

Optimizationofoperativeresultsrequiresthecarefulselectionofinstrumentsforthemacrosurgicalportionoftheoperation,performedwiththenakedeye,andthemicrosurgical part,performedwiththeeyeaidedbytheoperatingmicroscope(10,11).Inthepast,surgeonscommonlyusedonesetof instrumentsforconventionalmacrosurgeryperformedwith

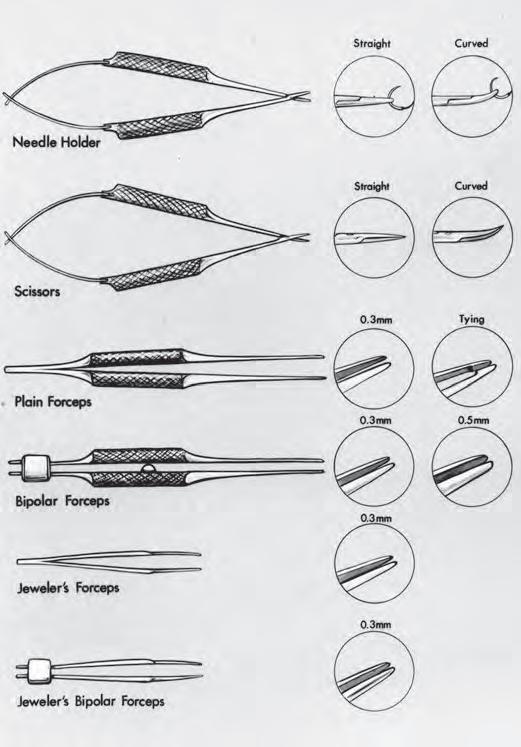

FIGURE1.6. Positioningofpatientsforacousticneuromaremovaland decompressionfortreatmentofhemifacialspasm. A and B,theheadofthe tableiselevated.Inourinitialuseofthethree-quarterproneposition,the headoftheoperatingtablewastiltedtoelevatetheheadonlyslightly(A). Itwaslaternoted,however,thatmoremarkedtiltingofthetablesignificantlyelevatedtheheadandreducedthevenousdistensionandintracranial pressure.Iusuallyperformoperationstotreatacousticneuromasand hemifacialspasmsittingonastoolpositionedbehindtheheadofthe patient.Inrecentyears,wehavetiltedthetabletoelevatetheheadtosuch adegreethatthesurgeon’sstoolmustbeplacedonaplatform(B).The patientshouldbepositionedonthesideofthetablenearestthesurgeon. C and D,thepatient’sheadisrotated.Thereisatendencytorotatetheface towardthefloorforacousticneuromaremoval(C).However,betteroperativeaccessisobtainedifthesagittalsutureisplacedparalleltothefloor (D).Rotatingthefacetowardthefloor(C)placesthedirectionofview throughtheoperatingmicroscopeforwardtowardtheshoulder,thusblockingorreducingtheoperativeangle.Positioningtheheadsothatthesagittalsutureisparalleltothefloor(D)allowsthedirectionofviewthrough theoperatingmicroscopetoberotatedawayfromtheshoulderandprovides easierwideraccesstotheoperativefield.Thepositionshownin D isalso usedfordecompressionoperationsfortreatmentofhemifacialspasm.The positionshownin C isusedfordecompressionoperationsfortreatmentof trigeminalneuralgia,inwhichthesurgeonisseatedatthetopofthe patient’shead,asshownin Figure1.3,ratherthanbehindthepatient’s head,asshownin B. E and F,itisbettertogentlytilttheheadtowardthe contralateralshoulderthantowardtheipsilateralshoulder.Tiltingthevertextowardthefloor,withthesagittalsutureparalleltothefloor,opensthe anglebetweentheshoulderandtheheadandincreasesoperativeaccess. G and H,extendingthenecktendstoshifttheoperativesitetowardthe prominenceoftheshoulderandupperchest,whereasgentleflexionopens theanglebetweentheupperchestandtheoperativesiteandbroadensthe rangeofaccesstotheoperativesite.

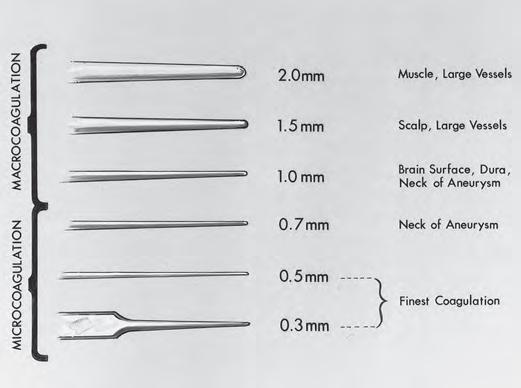

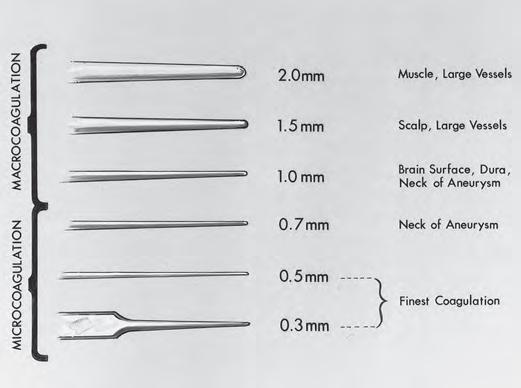

thenakedeyeandanotherset,withdifferenthandlesand smallertips,formicrosurgeryperformedwiththeeyeaided bythemicroscope.Atrendistoselectinstrumentswithhandlesandtactilecharacteristicssuitableforbothmacrosurgery andmicrosurgeryandtochangeonlythesizeoftheinstrumenttip,dependingonwhethertheuseistobemacrosurgical ormicrosurgical.Forexample,forcepsformacrosurgeryhave graspingtipsaslargeas2to3mmandthoseformicrosurgery commonlyhavingtipsmeasuring0.3to1.0mm.

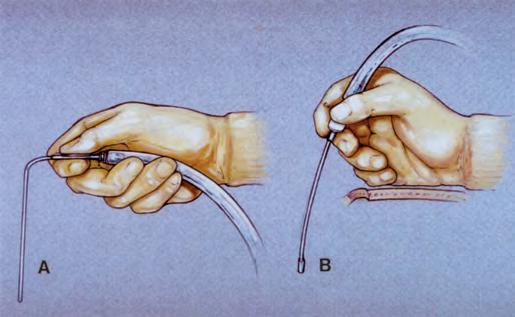

Ifpossible,theinstrumentsshouldbeheldinapencilgripbetweenthethumbandtheindexfinger,ratherthaninapistolgrip withthewholehand(Fig.1.7).Thepencilgrippermitstheinstrumentstobepositionedwithdelicatemovementsofthefingers,but thepistolgriprequiresthattheinstrumentsbemanipulatedwith thecoarsermovementsofthewrist,elbow,andshoulder.

Ipreferround-handleforceps,scissors,andneedle-holders, becausetheyallowfinermovement.Itispossibletorotate theseinstrumentsbetweenthethumbandforefinger,rather thanhavingtorotatetheentirewrist(Fig.1.8).Ifirstused

round-handleneedle-holdersandscissorstoperformsuperficialtemporalartery-middlecerebralarteryanastomoses,andI laternotedthattheadvantageofbeingabletorotatethe instrumentbetweenthethumbandthefingersalsoimproved theaccuracyofotherstraightorbayonetinstrumentsusedfor dissection,grasping,cutting,andcoagulation(Figs.1.9 and 1.10).Round-handlestraightorbayonetforcepsmaybeused forbothmacrosurgeryandmicrosurgery.

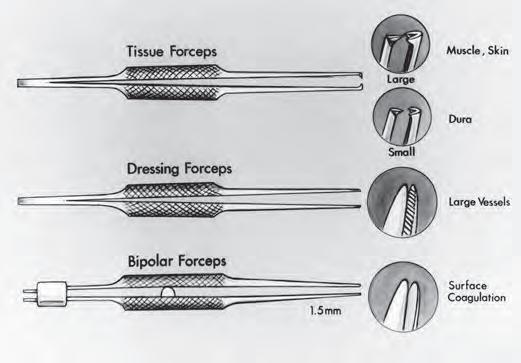

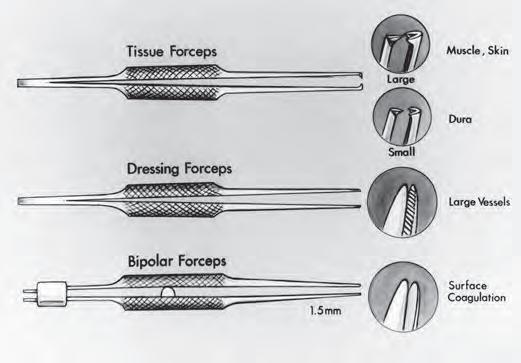

Theadditionofround-handlestraightforcepswithteeth, calledtissueforceps,increasestheusesofinstrumentswith roundhandlestoincludegraspingofmuscle,skin,anddura (Fig.1.11).Tissueforcepswithlargeteethareusedforthe scalpandmuscle,andoneswithsmallteethareusedforthe dura.Theadditionofround-handleforcepswithfineserrationsinsidethetips,calleddressingforceps,makestheset suitableforgraspingarterialwallsforendarterectomyand arterialsuturing.

Theinstrumentsshouldhaveadullfinish,becausethe brilliantlightfromhighlypolishedinstruments,whenre-

FIGURE1.7. Commonhandgripsforholdingsurgicalinstruments.The gripisdeterminedlargelybythedesignoftheinstrument. A,asuction tubeheldinapistolgrip.Thedisadvantagesofthistypeofgriparethatit usesmovementsofthewristandelbow,ratherthanfinefingermovements,topositionthetipoftheinstrumentandthehandcannotberested andstabilizedonthewoundmargin. B,asuctiontubeheldinapencil grip,whichpermitsmanipulationofthetipwithdelicatefingermovements,whilethehandrestscomfortablyonthewoundmargin.

flectedbackthroughthemicroscope,caninterferewiththe surgeon’svisionanddiminishthequalityofphotographs takenthroughthemicroscope.Sharpnessandsterilizationare notaffectedbythedullfinish.

Theseparationbetweentheinstrumenttipsshouldbewide enoughtoallowthemtostraddlethetissue,theneedle,orthe thread,tocutorgraspitaccurately.Theexcessiveopening andclosingmovementsrequiredforwidelyseparatedtips reducethefunctionalaccuracyoftheinstrumentduringdelicatemanipulationsundertheoperatingmicroscope.Thefingerpressurerequiredtobringwidelyseparatedtipstogether againstfirmspringtensionofteninitiatesafinetremorand inaccuratemovements.Microsurgicaltissueforcepsshould haveatipseparationofnomorethan8mm,microneedleholdertipsshouldopennomorethan3mm,andmicroscissorstipsshouldopennolessthan2mmandnomorethan5 mm,dependingonthelengthofthebladeandtheuseofthe scissors.

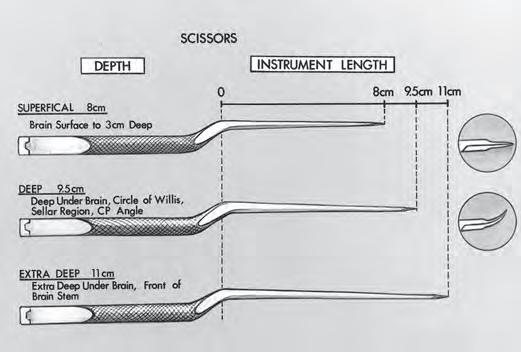

Thelengthoftheinstrumentsshouldbeadequateforthe particulartaskthatisbeingcontemplated(Figs.1.9 and 1.10). Bayonetinstruments(e.g.,forceps,needle-holders,andscissors)shouldbeavailableinatleastthethreelengthsneeded forthehandtoberestedwhilethesurgeonoperatesatsuperficial,deep,andextra-deepsites.

BayonetForceps

Bayonetforcepsarestandardneurosurgicalinstruments (Figs.1.9 and 1.10).Thebayonetforcepsshouldbeproperly balancedsothat,whenitshandlerestsonthewebbetweenthe thumbandindexfingerandacrosstheradialsideofthe middlefinger,theinstrumentremainstherewithoutfalling forwardwhenthegraspoftheindexfingerandthumbis released.Poorbalancepreventsthedelicategrasprequiredfor microsurgicalprocedures.

FIGURE1.8. StraightRhotoninstrumentswithroundhandlesandfine tips,foruseatthesurfaceofthebrain.Theseinstrumentsaresuitablefor microsurgicalprocedures,suchasextracranial-intracranialarterialanastomoses.Theinstrumentsincludeneedle-holderswithstraightandcurved tips,scissorswithstraightandcurvedtips,forcepswithplatformsfor tyingfinesutures,bipolarforcepswith0.3-and0.5-mmtips,andplain andbipolarjeweler’sforceps.Jeweler’sforcepscanbeusedasaneedleholderforplacingsuturesinfinemicrovascularanastomosesonthesurfaceofthebrain,butIpreferaround-handlestraightneedle-holderfor thatuse.

Itispreferabletotestforcepsfortensionandtactilequalities byholdingthemintheglovedhand,ratherthanthenaked hand.Forcepsresistancetoclosurethatisperceivedasadequateinthenakedhandmaybecomealmostimperceptiblein theglovedhand.Theforcepsmaybeusedtodeveloptissue planesbyinsertingtheclosedforcepsbetweenthestructures tobeseparatedandreleasingthetensionsothattheblades openandseparatethestructures.Thisformofdissection requiresgreatertensioninthehandlesthanispresentinsome delicateforceps.

Inselectingbayonetforceps,thesurgeonshouldconsider thelengthofthebladesneededtoreachtheoperativesiteand thesizeofthetipneededforthespecifictasktobecompleted. Bayonetforcepswith8-,9.5-,and11-cmblades,withavariety

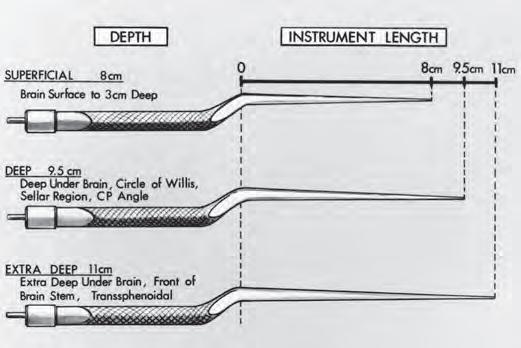

FIGURE1.9. Rhotonbayonetbipolarcoagulationforcepsforuseatdifferentdepths.Bayonetforcepswith8-cmbladesaresuitableforcoagulation onthesurfaceofthebrainanddowntoadepthof3cm.Bayonetforceps with9.5-cmbladesareneededforcoagulationdeepunderthebrain,inthe regionofthecircleofWillis,thesuprasellararea,orthecerebellopontine (CP)angle.Bayonetforcepswith11-cmbladesaresuitableforcoagulation inextra-deepsites,suchasinfrontofthebrainstemorintranssphenoidal exposures.Somesurgeonspreferthattheforcepsbecoated,toensurethat thecurrentisdeliveredtothetips,butthecoatingmayobstructtheview atthetipsduringproceduresperformedunderthemicroscope.

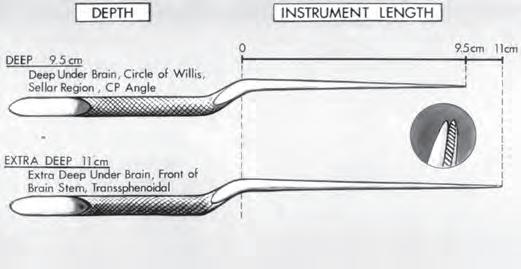

FIGURE1.10. Rhotonbayonetdissectingforcepswithfine(0.5-cm)tips, foruseatdeepandextra-deepsites.Finecross-serrationsinsidethetips (inset)facilitategraspingandmanipulationoftissue. CP, cerebellopontine.

oftipsizes(rangingfrom0.5to2.0cm),areneeded(Figs.1.9, 1.10, and 1.12).Bayonetforcepswith8-cmshaftsaresuitable foruseonthebrainsurfaceanddowntoadepthof2cm belowthesurface.Bayonetforcepswithbladesof9.5cmare suitableformanipulatingtissuesdeepunderthebrain,atthe levelofthecircleofWillis(e.g.,fortreatmentofananeurysm), inthesellarregion(e.g.,fortreatmentofapituitarytumorvia atranscranialapproach),andinthecerebellopontineangle (e.g.,forremovalofanacousticneuromaordecompressionof acranialnerve).Fordissectionandcoagulationinextra-deep sites,suchasinfrontofthebrainstemorinthedepthsofa transsphenoidalexposure,forcepswith11-cmbladesareused. Somesurgeonspreferthattheforcepsbecoatedwithan insulatingmaterialexceptatthetips,toensurethatthecurrent

FIGURE1.11. Rhotonstraightinstrumentswithroundhandlesneededto completetheset,sothatthesametypeofhandlescanbeusedformacrosurgeryperformedwiththenakedeyeandmicrosurgeryperformedwith theeyeaidedbythemicroscope.Forcepswithteeth,calledtissueforceps, areneededtograspdura,muscle,andskin.Smallteethareusedforthe dura,andlargeteethareusedfortheskinandmuscle.Forcepswithcrossserrations,calleddressingforceps,maybeusedduringendarterectomies onlargerarteries.Smooth-tipbipolarcoagulationforcepswith1.5-mmtips areusedformacrocoagulationoflargevesselsinthescalp,muscle,or dura.

FIGURE1.12. Forcepstipsneededformacro-andmicrocoagulation. Bipolarforcepswith1.5-and2-mmtipsaresuitableforcoagulationof largevesselsandbleedingpointsinthescalp,muscle,andfascia.The0.7and1-mmtipsaresuitableforcoagulationontheduraandbrainsurface andforcoagulationontumorcapsulesurfaces.Finecoagulationatdeep sitesintheposteriorfossaisperformedwithbayonetforcepswith0.5-mm tips.The0.3-mmtipissuitableforuseonshortinstrumentssuchasjeweler’sforceps.Whentipsassmallas0.3mmareplacedonbayonetforceps, thetipsmayscissorratherthanoppose.

isdeliveredtothetips,butthecoating,ifthick,mayobstruct theviewofthetissuebeinggraspedduringproceduresperformedunderthemicroscope.

Aseriesofbipolarbayonetforcepswithtipsof0.3to2.0mm allowcoagulationofvesselsofalmostanysizeencounteredin neurosurgery(Fig.1.12).Forcoagulationoflargerstructures, tipswithwidthsof1.5and2mmareneeded.Formicrocoagulation,forcepswith1.0-,0.7-,or0.5-mmtipsareselected. Fine0.3-mmtips(likethoseonjeweler’sforceps)placedon bayonetforcepsmayscissor,ratherthanfirmlyopposing, unlesstheyarecarefullyaligned.A0.5-mmtipisthesmallest thatispracticalforuseonmanybayonetforceps.Theforceps shouldhavesmoothtipsiftheyaretobeusedforbipolar coagulation.Iftheyaretobeusedfordissectionandgrasping oftissueandnotforcoagulation,thentheinsidetipsshould havefinecross-serrations(likedressingforceps)(Fig.1.10).To grasplargepiecesoftumorcapsule,forcepswithsmallrings withfineserrationsatthetipsmaybeused.

BipolarCoagulation

Thebipolarelectrocoagulatorhasbecomefundamentalto neurosurgerybecauseitallowsaccuratefinecoagulationof smallvessels,minimizingthedangerousspreadofcurrentto adjacentneuralandvascularstructures(Figs.1.9,1.12, and 1.13)(3,5).Itallowscoagulationinareaswhereunipolar coagulationwouldbehazardous,suchasnearthecranial nerves,brainstem,cerebellararteries,orfourthventricle.

Whentheelectrodetipstoucheachother,thecurrentis short-circuitedandnocoagulationoccurs.Thereshouldbe enoughtensioninthehandleoftheforcepstoallowthe

FIGURE1.13. MalisirrigationbipolarcoagulationunitwithcoatedRhotonbayonetcoagulationforceps.Asmallamountoffluidisdispensedat thetipoftheforcepsduringeachcoagulationstep.

surgeontocontrolthedistancebetweenthetips,becauseno coagulationoccursifthetipstouchoraretoofarapart.Some typesofforceps,whichareattractivebecauseoftheirdelicacy, compresswithsolittlepressurethatthesurgeoncannotavoid closingthemduringcoagulation,evenwithadelicategrasp. Thecableconnectingthebipolarunitandthecoagulation forcepsshouldnotbeexcessivelylong,becauselongercables cancauseanirregularsupplyofcurrent.

Surgeonswithexperienceinconventionalcoagulationare conditionedtorequiremaximaldrynessatthesurfaceof application,butsomemoistnessispreferablewithbipolar coagulation.Coagulationoccursevenifthetipsareimmersed insalinesolution,andkeepingthetissuemoistwithlocal cerebrospinalfluidorsalineirrigationduringcoagulationreducesheatingandminimizesdryingandstickingoftissueto theforceps.Fineirrigationunitsandforcepsthatdispensea smallamountoffluidthroughalongtubeintheshaftofthe forcepstothetipwitheachcoagulationstephavebeendeveloped(Fig.1.14).Toavoidstickingaftercoagulation,thepoints oftheforcepsshouldbecleanedaftereachapplicationtothe tissue.Ifcharredbloodcoatsthetips,thenitshouldberemovedbywipingwithadampclothratherthanbyscraping withascalpelblade,becausetheblademayscratchthetips andmakethemmoreadherenttotissueduringcoagulation. Thetipsoftheforcepsshouldbepolishediftheybecome pittedandrough.

Scissors

Scissorswithfinebladesonstraightorbayonethandlesare frequently usedformicrosurgicalprocedures(Figs.1.8 and 1.15).

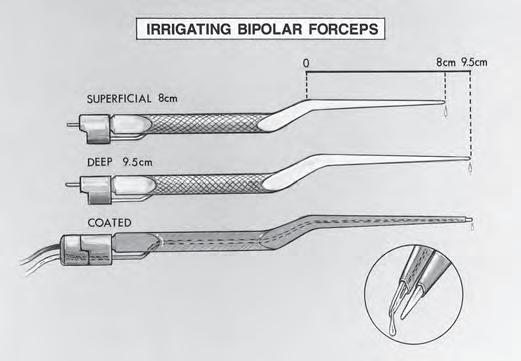

FIGURE1.14. Rhotonirrigatingbipolarforceps.Asmallamountoffluid isdispensedatthetipoftheforcepsduringeachcoagulationstep.The smallmetaltubethatcarriestheirrigatingfluidisinlaidintotheshaftof theinstrument,sothatitdoesnotobstructtheviewoftheoperativesite whenthesurgeonislookingdowntheforcepsintoadeepnarrowoperative site.Irrigatingforcepswith8-cmbladesaresuitableforcoagulationator nearthesurfaceofthebrain.Bayonetforcepswith9.5-cmbladesareused forcoagulationdeepunderthebrain.Somesurgeonspreferthattheforcepsbecoated,toensurethatthecurrentisdeliveredtothetips,butthe coatingmayobstructtheviewatthetipsduringproceduresperformed underthemicroscope.

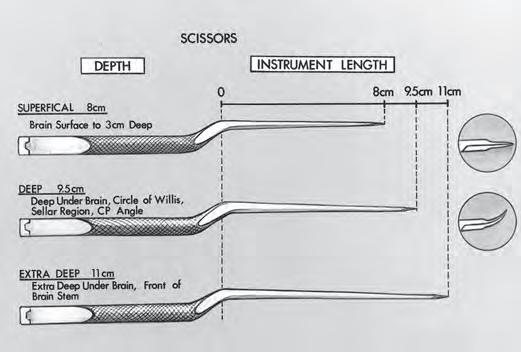

FIGURE1.15. Rhotonbayonetscissorswithstraightandcurvedblades. Thebayonetscissorswith8-cmshaftsareusedatthesurfaceofthebrain anddowntoadepthof3cm.Thescissorswith9.5-cmshaftsareused deepunderthebrain,atthelevelofthecircleofWillis,thesuprasellar area,andthecerebellopontine(CP)angle.Thescissorswith11-cmshafts areusedatextra-deepsites,suchasinfrontofthebrainstem.Thestraight nonbayonetscissorsshownin Figure8 mayalsobeusedatthesurfaceof thebrain.

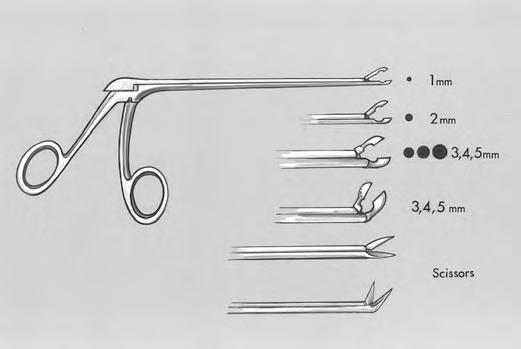

Cutting shouldbeperformedwiththedistalhalfoftheblade. Ifthescissorsopentoowidely,thencuttingabilityandaccuracysuffer.Delicatecuttingnearthesurface,suchasopening ofthemiddlecerebralarteryforanastomosisorembolectomy, shouldbeperformedwithstraight(notbayonet)scissorswith finebladesthatareapproximately5mmlongandopenapproximately3mm.Onlydelicatesuturematerialandtissue shouldbecutwithsuchsmallblades.Bayonetscissorswith 8-cmshaftsandcurvedorstraightbladesareselectedforareas 3to4cmbelowthecranialsurface.Bayonetscissorswith 9.5-cmshaftsareselectedfordeepareas,suchasthecerebellopontineangleorthesuprasellarregion.Thebladesshould measure14mminlengthandshouldopenapproximately4 mm.Forextra-deepsites,suchasinfrontofthebrainstem,the scissorsshouldhave11-cmshafts.Scissorsonanalligator-type shankwithalongshaftareselectedfordeepnarrowopenings, asintranssphenoidaloperations(Fig.1.16).

Dissectors

Themostwidelyusedneurosurgicalmacrodissectorsareof thePenfieldorFreertypes;however,thesizeandweightof theseinstrumentsmakethemunsuitableformicrodissection aroundthecranialnerves,brainstem,andintracranialvessels. ThesmallestPenfielddissector,theno.4,hasawidthof3mm. Formicrosurgery,dissectorswith1-and2-mmtipsareneeded (Fig.1.17).Straight,ratherthanbayonet,dissectorsarepreferredformostintracranialoperations,becauserotatingthe handleofastraightdissectordoesnotalterthepositionofthe tipbutrotatingthehandleofabayonetdissectorcausesthetip tomovethroughawidearc.

Round-tipdissectors,calledcanalknives,areusedforseparationoftumorfromnerve(Figs.1.17–1.19).Analternative

FIGURE1.16. Straightandangledalligatorcupforcepsandscissors. Thesefinecupforcepsareusedtograspandremovetumorsindeepnarrowexposures.A2-,3-,or4-mmcupisrequiredformostmicrosurgical applications,butcupforcepsassmallas1mmoraslargeas5mmare occasionallyneeded.Straightandangledalligatorscissorswiththesame mechanismofactionasthecupforcepsarerequiredfordeepnarrowexposures,asinthedepthsoftranssphenoidalapproaches.

methodoffinedissectionistousethestraightpointedinstrumentsthatIcallneedles(7).Itmaybedifficulttograspthe marginofthetumorwithforceps;however,asmallneedle dissectorintroducedintoitsmarginmaybehelpfulforretractingthetumorinthedesireddirection(Figs.1.18B and 1.19A). Thistypeofpointedinstrumentcanalsobeusedtodevelopa cleavageplanebetweentumorandthearachnoidmembrane, nerves,andbrain.Spatuladissectorssimilarto,butsmaller than,theno.4Penfielddissectorarehelpfulindefiningthe neckofananeurysmandseparatingitfromadjacentperforatingarteries.The40-degreeteardropdissectorsareespeciallyhelpfulindefiningtheneckofananeurysmandin separatingarteriesfromnervesduringvasculardecompressionoperations,becausethetipslideseasilyinandoutoftight areas,withoutinadvertentlyavulsingperforatingarteriesor catchingondelicatetissue(Figs.1.20 and 1.21)(9,13).

Anyvessellocatedabovethesurfaceofanencapsulated tumor,suchasanacousticneuromaormeningioma,shouldbe initiallytreatedasifitwereabrainvesselrunningoverthe tumorsurfacethatcouldbepreservedwithaccuratedissection.Thesurgeonshouldtrytodisplacethevesselandadjacenttissuefromthetumorcapsuletowardtheadjacentneural tissueswithasmalldissector,afterthetumorhasbeenremovedfromwithinthecapsule.Vesselsthatinitiallyappearto beadheringtothecapsuleoftenprovetobeneuralvesselson thepialsurfacewhendissectedfreeofthecapsule.

Ifthepia-arachnoidmembraneisadheringtothetumor capsuleorifatumormassispresentwithinthecapsuleand preventscollapseofthecapsuleawayfromthebrainstemand cranialnerves,thenthereisatendencytoapplytractionto bothlayersandtotearneuralvesselscoursingonthepial surface.Beforeseparatingthepia-arachnoidmembranefrom thecapsule,itisimportanttoremoveenoughtumorsothat thecapsuleissothinitisalmosttransparent.Ifthesurgeonis

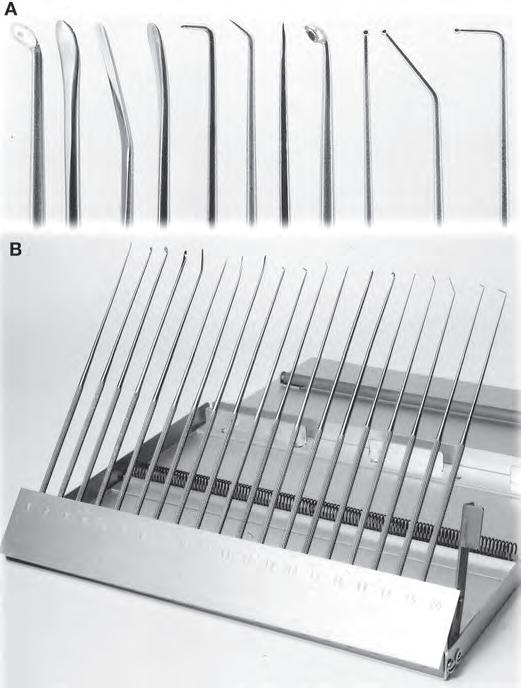

FIGURE1.17. Rhotonmicrodissectorsforneurosurgery. A,theinstrumentsshown(from left to right)arefourtypesofdissectors(round,spatula,flat,andmicro-Penfield),aright-anglenervehook,angledand straightneedledissectors,amicrocurette,andstraight,40-degree,and right-angleteardropdissectors. B,astoragecasepermitseasyaccesstothe instrumentsandprotectstheirdelicatetipswhentheyarenotinuse.The fullsetincludesroundandspatuladissectorsin1-,2-,and3-mmwidths, straightandangledmicrocurettes,longandshortteardropdissectorsin 40-degreeandright-angleconfigurations,andonestraightteardrop dissector.

uncertainregardingthemarginbetweenthecapsuleandthe pia-arachnoidmembrane,thenseveralgentlesweepsofa smalldissectorthroughtheareacanhelpclarifytheappropriateplanefordissection.

Fortranssphenoidaloperations,dissectorswithbayonet handlesarepreferredbecausethehandleshelppreventthe surgeon’shandfromblockingtheviewdownthelongnarrow exposureofthesella(Fig.1.22)(8).Bluntringcurettesare frequentlyusedduringtranssphenoidaloperations,toremove smallorlargetumorsofthepituitaryglandandtoexplorethe sella(Figs.1.23–1.26).

Needles,Sutures,andNeedle-holders

Theoperatingroomshouldhavereadilyavailablemicrosuturesrangingfrom6-0to10-0,onavarietyofneedles(ranging indiameterfrom50to130 m)(Table1.1)(18).Forthemost

delicatesuturing,asinextracranial-intracranialarterialanastomoses,nylonorProlenesuturesof22- mdiameter(10-0)on needlesofapproximately50-to75- mdiameterareused.

Jeweler’sforcepsarecommonlyusedtograspmicroneedles, buttheyaretooshortformostintracranialoperations.The handlesofthemicroneedle-holdersshouldberound,rather thanflatorrectangular,sothatrotatingthembetweenthe fingersyieldsasmoothmovementthatdrivestheneedle easily(Figs.1.8 and 1.27).Thereshouldbenolockorholding catchonthemicroneedle.Whensuchalockisengagedor released,regardlessofhowdelicatelyitismade,thetipjumps, possiblycausingmisdirectionoftheneedleortissuedamage.

Jeweler’sforcepsorstraightneedle-holdersaresuitablefor handlingmicroneedlesnearthecorticalsurface(Fig.1.8).For deeperapplications,bayonetneedle-holderswithfinetips maybeused(Fig.1.27).Bayonetneedle-holderswith8-cm shaftsaresuitableforusetoadepthof3cmbelowthesurface ofthebrain.Shaftsmeasuring9.5cmareneededforsuturing ofvesselsornervesindeeperareas,suchasinthesuprasellar region,aroundthecircleofWillis,orinthecerebellopontine angle.Totiemicrosutures,microneedle-holders,jeweler’sforceps,ortyingforcepsmaybeused.Tyingforcepshavea platforminthetiptofacilitategraspingofthesuture;however,mostsurgeonsprefertotiesutureswithjeweler’sforceps orfineneedle-holders.

SuctionTubes

Suctiontubeswithbluntroundedtipsarepreferred.Dandy designedandusedbluntsuctiontubes,andhistraineeshave continuedtousetheDandytypeoftube(Fig.1.28)(16). Yas ¸ argiletal.(19)andRhotonandMerz(16)reportedtheuse ofsuctiontubeswithbluntroundedtips,whichallowedthe tubestobeusedforthemanipulationoftissueaswellasfor suction.Thethickeningandroundingofthetipsreducethe problemofthesmall3-and5-Frenchtubesbecomingsharp whentheyaresmoothlycutatrightanglestotheshaft.Some suctiontubes,suchasthoseofthecurvedAdsontype,become somewhatpointedwhenpreparedinsizesassmallas3or5 French,becausethedistalendofthetubeiscutobliquelywith respecttothelongaxisoftheshaft,makingthetubesless suitableforusenearthethinwallsofaneurysms.

Suctiontubesshouldbedesignedtobeheldlikeapencil, ratherthanlikeapistol(Fig.1.7).Fraziersuctiontubesare designedtobeheldlikeapistol.Thepencilgripdesignfrees theulnarsideofthehandsothatitcanberestedcomfortably onthewoundmargin,affordingmoreprecise,moredelicate, andsturdiermanipulationofthetipofthesuctiontubethanis allowedwiththeunsupportedpistolgrip.

Selectingatubeofappropriatelengthisimportantbecause thearmtiresduringextendedoperationsifthesuctiontubeis toolongtoallowthehandtoberested(Figs.1.29 and 1.30).Tubes with 8-cmshafts(i.e.,thedistancebetweentheangledistalto thethumbpieceandthetip)areusedforsuctionatthelevel ofthecraniumornearthesurfaceofthebrain(Fig.1.31).Tubes with 10-cmshaftsallowthehandtorestalongthewound marginduringproceduresperformedindeepoperativesites, suchasinthecerebellopontineangle,suprasellar,orbasilar