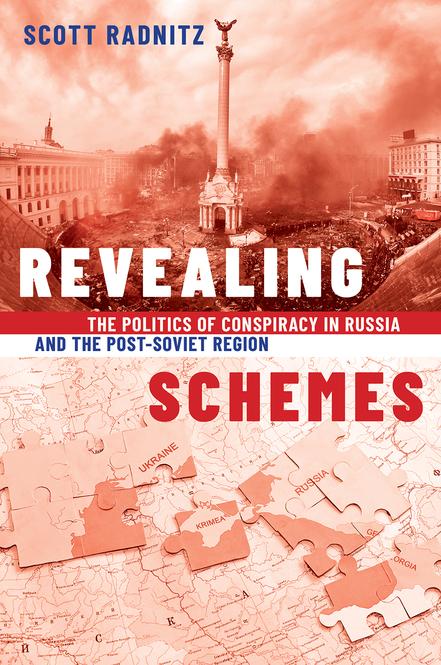

Revealing Schemes

The Politics of Conspiracy in Russia and the Post-Soviet Region

SCOTT RADNITZ

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Radnitz, Scott, 1978– author.

Title: Revealing Schemes : the politics of conspiracy in Russia and the post-Soviet region / Scott Radnitz. Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020056491 (print) | LCCN 2020056492 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197573532 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197573549 (paperback) | ISBN 9780197573563 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Conspiracy theories—Russia (Federation) | Conspiracy theories—Former Soviet republics. Classification: LCC HV6275.R33 2021 (print) | LCC HV6275 (ebook) | DDC 001.9/80947—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020056491

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020056492

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197573532.001.0001

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Paperback printed by Marquis, Canada

Hardback printed by Bridgeport National Bindery, Inc., United States of America

3.

4.

5.

5.1.

5.4.

5.5.

7.1.

7.5. Plane crash vignette: Likelihood plane wаs deliberately shot down

7.6. Protest vignette: Support of official for higher office

7.7. Protest vignette: Support for official to address protesters’ demands

7.8. Levels of conspiracism and behavioral outcomes

A.1. Conspiracy claims by sampling method

2.1.

5.2.

6.2.

Preface and Acknowledgments

As with many of the most important insights in life, this one came from talking to a taxi driver. When I was in Kyrgyzstan in the early 2000s, the driver casually mentioned to me that Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev had actually been working for the CIA. How else to account for the country’s unexpected collapse? This was only one of many conspiracy theories I came across while researching for my first book, and I took notice of how they pervaded everyday life and often anchored people’s understanding of politics. I thought it would be interesting to one day study conspiracy theories, but the topic seemed too overwhelming to wrangle into a manageable research project. Later, as the study of conspiracy theories become a growth area in political science, I realized that there were critical unexplored questions on the role these theories play in non-Western countries and how they are used as political rhetoric.

In hindsight, the seed for this book was probably planted much earlier. My development of political awareness in the 1990s coincided with a resurgence of conspiracy theories in the United States, from the imminent incursion of the UN’s black helicopters to the renewed interest in the Kennedy assassination after the release of Oliver Stone’s film JFK. Yet conspiracy theories were still relegated to the fringes of American politics and remained, at most, an entertaining diversion. So, when I seriously set to work on this project, anchored in the post-Soviet world, I anticipated having to convince Western audiences that public officials who spread conspiracy theories were worthy of serious inquiry. I was also concerned that my book risked reinforcing negative stereotypes about the region and inadvertently pandering to readers who might be tempted to feel smug about how dysfunctional and seemingly irrational politics was over there in shambolic, autocratic countries that the Enlightenment had apparently reached too late. My concerns turned out to be misguided. After I began collecting data for this book in 2014, I observed uncanny and disturbing parallels between the conspiracy claims I was reading and the current events I was witnessing—in the United States. As I wrote this book, the Provocateur-in-Chief barked and blustered in the background, personifying the mainstreaming of conspiracy theories in American political discourse. In some sense, he was my co-conspirator in this project, as he simplified the task of making the case for the broader significance of my research.

In 2015, I attended what was probably the first-ever conference on conspiracy theories—a gathering about which the jokes write themselves—organized by

Joseph Uscinski at the University of Miami. As this event occurred while my ideas were still in formation, it was especially valuable to see the different ways in which scholars approached the topic. The fact that only a handful of presenters were examining cases outside the United States or Western Europe also reaffirmed my sense that the field would benefit from knowledge of conspiracy theories in other countries. A follow-up conference in 2020 was unfortunately canceled only days before it was supposed to start, due to Covid-19—timing that was perhaps too coincidental?

I have presented various parts of this manuscript at conferences and workshops over the years. I am grateful to the Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities (CRASSH) at the University of Cambridge for flying me out to give a talk through their Conspiracy and Democracy program, and to the Russia Institute at King’s College London for hosting me. I also received useful feedback presenting my work in progress at the Caucasus Research Resource Center in Tbilisi, Indiana University, and several conferences and workshops convened by PONARS Eurasia.

I have benefited enormously from the insights of colleagues at various stages, whether informally or as conference discussants, including Gulnaz Sharafutdinova, Sam Greene, Valerie Bunce, Hugo Drochon, Sergiy Kudelia, Mark Beissinger, Georgi Derluguian, Gerard Toal, Valerie Sperling, Tim Blauvelt, John Heathershaw, Ora John Reuter, Marc Berenson, Serghei Golunov, Marianne Kamp, Andrew Neal, Joe Uscinski, Marlene Laruelle, Josh Tucker, John Payne, and Harris Mylonas. I received especially valuable and intensive feedback on large parts of the manuscript from Julie George, Larry Markowitz, and Carol Williams.

At the University of Washington, I am fortunate to have many colleagues who provided insights and assistance, especially Dan Chirot, Saadia Pekkanen, Daniel Bessner, Vanessa Freije, Rick Lorenz, Steve Pfaff, Katy Pearce, Glennys Young, Sunila Kale, David Bachman, Yuan Hsiao, Elena Campbell, and Guntis Smidchens. Reşat Kasaba was consistently supportive of my work in his capacity as director of the Jackson School of International Studies.

I received vital funding for this book from various parts of UW. Being a fellow at the Simpson Center for the Humanities enabled me to share my work with interdisciplinary scholars early on in the project. The College of Arts and Sciences provided resources through the Ellison Center for Russian, East European, and Central Asian Studies, whose funds I was able to draw on while serving as director for eight years. The Royalty Research Fund provided me with the resources to conduct surveys and focus groups in Georgia and Kazakhstan. I also benefited from organizing a workshop on the politics of fifth columns, also sponsored by the Simpson Center.

Data collection was a collective endeavor. It took a dozen research assistants over several years to amass hundreds of conspiracy theories. These students were brave enough to plunge into the abyss of twisted allegations and insidious schemes, and may never look at the world the same way again: Oleksandra Makushenko, Konstantin Manko, Alyssa Machado, Malkhaz Saldadze, Fedor Pogulsky, Anatoliy Klots, Lina Wang, Indra Ekmanis, Anara Satkeeva, Jessica Doscher, Jessica Meyerzon, and Hannah Standley. ACT was my partner on the ground in Georgia and Kazakhstan, where I benefited from the expertise of Tamuna Babukhadia, Tatiana Voronina, and Nino Kokosadze.

I owe thanks to Oxford University Press for its speedy reviews and smooth production process. David McBride was extremely responsive and supportive of my vision for this book. Anonymous reviewers provided productive and encouraging feedback.

Closer to home, my thinking about post-Soviet conspiracy theories was shaped by many discussions with my father-in-law (sometimes over vodka), whose views about the nefarious hidden hand of Russia in all disagreeable matters in the region offered insights into the ways people make sense of global events. Rahima was a patient and inspiring collaborator in the conspiracy of this book, especially during long summer days when I undertook clandestine work in various Seattle cafes. Milena and Oscar both came along during this project’s development and provided an impetus to get this book finished. Opportunities for them to get involved in many great conspiracies await. The book is dedicated to them.

Conspiracy Claims after Communism

On February 21, 2014, months of protests in the streets of Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv, reached a violent crescendo when government security forces opened fire on peaceful demonstrators. Embattled President Yanukovych, in a hastily convened meeting involving representatives from the political opposition and the European Union—but over Russian opposition—agreed to a new election that could lead to his removal. However, even as he signed the document, his security forces were melting away.1 Yanukovych was forced to flee the capital, and within hours his government was replaced by members of the opposition, which immediately began to undo Yanukovych’s legacy.

This sudden and surprising turn of events did not sit well with the Russian Federation, whose Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a press release in response. First, it exaggerated the new government’s actions, criticizing its “ban on the Russian language, lustration [removal of officials from public life], the liquidation of parties and organizations, the closure of objectionable media, and the removal of restrictions on the propaganda of neo-Nazi ideology.” Then, it darkly alluded to a Western-led conspiracy: “one does not see concern for the fate of Ukraine, but a one-sided geopolitical calculation. . . . It is a lasting impression that the Agreement of February 21, with the tacit consent of its external sponsors, is used only as a cover for promoting the scenario of a forced change of power in Ukraine.”2

The idea of a conspiracy hatched in the West against Ukraine—and by extension, Russia—while perhaps jarring to the uninitiated, was a familiar trope to the Kremlin’s audiences, both within and outside Russia. Two years earlier, then prime minister Vladimir Putin responded to massive protests in Moscow by claiming that Secretary of State Hillary Clinton had given the “signal to some figures in Russia, and they began active work” of publicly expressing their disapproval of his return to the presidency.3 The theme of Western support for democratic movements as a means to gain geopolitical influence was part of an ongoing storyline promoted by the Putin regime. So it was hardly surprising when Russian television personalities, analysts, reporters, and officials promoted the narrative that fascists had taken over Ukraine, that Western intelligence had

backed a coup d’état, and that both entities sought to persecute ethnic Russians in Ukraine—all in service of a plan by the West to overthrow Putin and weaken Russia. Analysts labeled this Kremlin-led propaganda campaign a “war on information”4 and compared Putin to Joseph Stalin5 and Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels.6

Troubling as this may be, it is not only Russians, and not only presidents (or their foreign ministries) who use conspiratorial rhetoric. Politicians in other countries have been known to level claims of conspiracy as well. During Ukraine’s mass protests, the chairman of the local parliament in Ukraine’s Crimea echoed the Kremlin line by warning that “there can be no election until the people armed with western countries’ money leave the country.”7 On the opposing side, a leader of the anti-Russian far-right opposition in Ukraine alleged, with no evidence, that “the Ukrainian Rada [legislature] is bribed and controlled by the Kremlin.”8

If we look further afield, we can find government officials who voice conspiracy claims in a wide range of situations. In another instance of alleged foreign interference, the former president of Georgia, Eduard Shevardnadze, claimed that the so-called Rose Revolution, which led to his ouster, was funded by American philanthropist George Soros.9 Not all conspiracies are international; some take place entirely on domestic soil, as when Kyrgyz General Felix Kulov conveniently blamed ethnic rioting on the relatives of the recently deposed president. He claimed—again, with no evidence—that “the family that lost power was intent not only on the clash of Uzbeks and Kyrgyz, but also provoking a conflict between Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan.”10

Beyond the post-Soviet region, conspiracy theories have recently moved from the margins of society to the center of politics. At a time when people have lost confidence in their political systems, leaders such as Hungary’s Victor Orban and Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan have amassed power in part by using rhetoric that pits supporters against outsiders. By invoking and inflating threats, “illiberal democrats” have cast themselves as uniquely qualified to protect the nation from insidious enemies.11

Conspiratorial rhetoric has also become a major force in US politics. Candidate Donald Trump’s claim that President Obama was not born in the United States catapulted him to the Republican presidential nomination. In office, he continued to allege conspiracies against himself, involving, among others, the Democratic Party, the FBI, the CIA, Hillary Clinton, George Soros, members of Congress, immigrants, the government of Ukraine, and the Emmy Awards. In many instances his claims, though outlandish to many, were echoed by prominent elected officials and accepted without question by his political base.12

They Are All Around Us

Conspiracy theories are enjoying a moment in the spotlight. They seem to be surfacing everywhere—on cable television, around dinner tables, in taxis and Ubers, on social media—and appear to be propagating themselves at amazing speeds. Studies have shown that large numbers of people across the globe believe conspiracy theories. For example, more than half of Americans and 60% of Britons believe at least one.13 A majority of people in a 17-nation survey disagreed that al-Qaeda was responsible for the terrorist attacks in the United States on September 11, 2001.14 In the spring of 2020, nearly one-third of Americans believed the Covid-19 virus was “created and spread on purpose.”15 The apparent spike in conspiracy theories in recent years has been matched by rising interest from journalists, scholars, policymakers, and ordinary citizens, who are variously fascinated or alarmed by the implications for democracy and the quality of public debate.

Belief in conspiracy theories may be troubling, but should it be cause for alarm? People have always believed in myths, superstitions, rumors, and sundry falsehoods, and some portion of the public will naturally suspect the powerful of committing terrible misdeeds. But agitated conspiracists scribbling their thoughts on paper or chatting with like-minded hobbyists over the Internet usually do not directly impact public policy or threaten anyone’s well-being. In and of itself, popular conspiracism is not a threat to democracy or the public’s wellbeing.16 In fact, it can even have salutary effects, insofar as it helps reveal actual government conspiracies.17

The stakes are higher when government officials promote conspiracy theories. States possess extraordinary amounts of information and have the wherewithal to withhold, misrepresent, or manipulate what they communicate to the public. Because governments carry the loudest megaphones, conspiracy claims promoted by elected or appointed officials are guaranteed to reach a broad audience. When governments weaponize conspiracy claims by aiming them at specific groups or individuals, it can result in tangible and significant harms: exclusion, harassment, and even violence.

We do not need to look far back in history to find examples of officially sanctioned conspiracy theories used toward injurious ends. The Nazis used the contrived notion of an international Jewish conspiracy to justify the persecution and ultimately extermination of Europe’s Jewish populations.18 In 1994, a governmentcontrolled radio station in Rwanda incited ethnic Hutus to commit genocide by describing “alleged, and unsubstantiated, Tutsi atrocities against the Hutus.”19 The US government used conspiracy theories about Soviet infiltration to persecute political enemies during the Cold War.20 President Trump’s conspiracy narrative

that the 2020 election had been stolen from him led directly to the attack on the US Capitol on January 6, 2021 and resulted in at least five deaths. Across much of the world today, the scapegoating of immigrants, the demonization of human rights advocates, and allegations of disloyalty by “globalists” and “fifth columns” echo rhetoric that was used to such devastating effect in the previous century.21

It is tempting to ascribe the deliberate promotion of conspiracy theories by those in power to personal defects. German Chancellor Angela Merkel captured this sentiment when she suggested that Putin was “not was in touch with reality” and was “in another world” in the weeks after Euromaidan.22 This view dovetails with the dominant way in which cultural critics and psychologists have regarded belief in conspiracy theories more generally—as the product of a “paranoid style”23 or “our brain’s quirks and foibles.”24

Another view sees official conspiratorial rhetoric not as misguided thinking, but as part of a strategy of deception intended to firm up dictatorship. Historian Timothy Snyder argues that Putin adopted the principles of an early twentiethcentury fascist philosopher as he sought to “create a bond of willing ignorance with Russians, who were meant to understand that Putin was lying but to believe him anyway.”25 A related perspective sees Russia’s anti-Ukraine propaganda as an effort not to persuade audiences that it was true, but rather to leave people “confused, paranoid, and passive” and locked into a “Kremlin-controlled virtual reality.”26 In these explanations, it is not Putin’s delusion but his cunning and lust for power that account for conspiracism in Russia’s upper echelons.

Politics, Not Personality

In contrast to approaches that focus on the characteristics of people who believe them or the personalities of those who utter them, this book examines conspiracy claims in their political context. It explores the reasons that regimes—the ruling collective of a country—make conspiracy claims, how they sustain them over time, and what effects those claims have on politics and society. I argue that in places where there are few trusted, neutral institutions to adjudicate the truth—a reality in much of the world—conspiracy claims function as a weapon of rhetorical combat. They are deployed to mark out positions, shape the discursive battlefield, and create an impression of dominance without (necessarily) inflicting physical force. In short, conspiracy theories are used with the aim of gaining political advantage.

The following chapters will show that conspiracy claims are not usually the preferred tactic of scheming dictators seeking to keep their citizens distracted and divided. Instead, they tend to emerge from political uncertainty. One impetus for conspiracism is the occurrence of unexpected and politically threatening events.

For those occupying positions of power, who are cognizant of public opinion and wary of being perceived as incompetent or vulnerable, identifying a conspiracy is a demonstration of knowledge and an assertion of control. It is intended to send a signal to potentially rival politicians and attentive citizens that the regime is resilient at a moment that is fraught with peril.

Allegations of conspiracy are also prone to appear where politics is more open and incumbent leaders must appeal to voters to stay in power. Because the media in politically competitive settings are usually somewhat independent of the state, news about the regime’s “dirty laundry”—intrigue, corruption, and backstabbing—often reaches the public. People in power, seeking to seize control of the narrative, can use conspiracy claims to discredit their rivals, create a pretext for harassment, and anticipate embarrassing defections from the ruling circle. There is even more kindling for conspiracism in societies that are polarized along ideological or regional lines or that are (believed to be) vulnerable to foreign penetration. Polarization and foreign influence heighten political animosities and make conspiracy theories appear more plausible. In short, the wielders of conspiracism, far from being master manipulators, are most likely to enter the fray in moments of uncertainty and threat.

Yet conspiracy theories can also be habit-forming. Rulers who anticipate future challenges to their façade of control may decide to propagate conspiracy claims even if they do not face immediate threats. An ongoing narrative of conspiracy acts like an insurance policy for those in power, demonstrating that they have anticipated new threats that may emerge and have identified the likely perpetrators in advance. But this scheme carries hazards: If conspiracy becomes the default account for certain types of events, the public may become inured to a heightened level of anxiety. This can lock rulers into a cycle of ever-increasing alarmism and can lead citizens to wonder what the government has done to acquire so many detractors.

To summarize, I argue that conspiracy theories may arise in varying circumstances because they have some attractive qualities, even though they also carry risks. They are an outgrowth of urgent threats to political authority, yet they can persist as part of an official narrative even where threats have subsided. In order to explore the causes, consequences, and contradictions of conspiracism in politics, this book focuses on a part of the world that has been associated with conspiracy theories as well as actual conspiracies.

Russia and Its Neighbors: Fertile Conspiratorial Soil?

From the Protocols of the Elders of Zion an anti-Semitic pamphlet first circulated by the tsarist secret police in the early twentieth century—to claims that

NATO is intent on looting Russia’s resources, Russia has produced more than its share of prominent conspiracy theories. Whether due to the country’s lack of natural defenses, its halting attempts to modernize, or its ambivalence about its place in the world, Russian intellectuals and political leaders have sometimes promoted a version of history as a series of Russophobic plots.27 During the Cold War, and more recently under Putin, the Kremlin has exported some of its conspiracy theories to the West.28

Russia has received a good deal of attention of late due to its size, geopolitical importance, and efforts to undermine democracy abroad. But Russia is not the only country in the region where the notion of conspiracy might resonate. The other post-Soviet states, in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia, were exposed to the same ideas and practices as Russia by virtue of being part of a single cultural and media space for decades. They all were subjected to Soviet propaganda, endured Stalinism, experienced a political opening under perestroika, and gained independence at the same time, in 1991. Today, ordinary citizens in the region consume Russian media and maintain personal ties across national borders. Leaders in Russia’s so-called near abroad learn and borrow from their counterparts in neighboring states, and many prevailing governance practices originate in the Kremlin. In other words, what happens in Russia does not necessarily stay in Russia. To look at any country in isolation is to neglect common historical experiences and the contemporary flow of ideas—including conspiratorial ones—across borders.

At the same time, the post-Soviet states have diverged since 1991 in important ways. One critical factor is the level of political openness, which includes considerations like the fairness of elections and the extent of media freedom. Aside from the Baltic states, which are considered fully democratic, the region consists of “hybrid” regimes like Moldova and Georgia; unbridled autocracies like Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan; and others, such as Russia, in between those extremes.

Another important dynamic is the geopolitical alignments of countries in the region. Belarus, Armenia, and Kazakhstan are (mostly) pro-Russian and Georgia is (mostly) pro-Western, while others, including Ukraine and Moldova, move between the two sides. Countries that partner, or seek to become aligned, with Russia or the United States can signal their shared interests or identity by adopting the larger country’s political rhetoric.29 Having common enemies is a good way to solidify friendships. Both these factors—political openness and foreign orientation—will come into play as we explore when and how conspiracy theories are used in politics.

Analyzing conspiracy theories in the post-Soviet region represents an overdue corrective in a field dominated by research in WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic)30 countries.31 Due to this narrow geographical

and cultural focus, belief in conspiracy theories has typically been understood as an aberration from the norm—a form of misguided thinking at odds with rational democratic discourse.32 Yet what should be considered “normal” is now a matter of debate in light of the rising prominence of conspiracism in democratic countries, most notably in the United States. Studying the post-Soviet world, where citizens have long regarded their abusive governments with contempt, can shed new light on questions that have been asked predominantly where citizens have historically trusted the state.33 For example, where there is less democracy, are citizens more likely to believe conspiracy theories? Does the surface plausibility of conspiracy theories make them more attractive as political rhetoric? And, where people are suspicious of power, are politicians who tout conspiracy theories viewed more or less favorably than those who do not?

How to Study the Politics of Conspiracy

This book makes headway on these questions in several ways. To explain where, when, and how politicians use conspiracy claims, I created a database of over 1,500 conspiracy claims from 12 post-Soviet states (the 15 republics minus the Baltics) from 1995 to 2014.34 I first examine multiple countries over time to make broad inferences about the factors that drive conspiracy claims, and then scrutinize individual countries to understand how they operate in context. In Russia, I show how the promotion of conspiracy claims by the government evolved over time and intensified in response to a series of critical challenges. I then look in detail at four other cases—Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia, and Kyrgyzstan—to show how conspiracy claims were shaped by their levels of political competition and geopolitical orientations. These chapters describe the invocation of conspiracy by government actors and their rivals within specific political contexts. They temporarily leave aside the question of whether conspiracy claims have meaningful impacts on society and politics—in other words, whether they matter

Later in the book, I address this question directly by examining how the intended audiences of conspiracy claims—ordinary citizens of post-Soviet states— respond to them. For that analysis, I conducted 12 focus groups and surveys of 2,000 respondents in Georgia and Kazakhstan. These countries offer contrasts in two important areas: regime and geopolitical alignment. Georgia is more democratic and pro-West, whereas Kazakhstan is more authoritarian and is closely tied to Russia. These national-level differences come into play when studying individuals. The surveys reveal what types of conspiracy claims people are inclined to believe, how they regard conspiracy-touting politicians, and how conspiracy beliefs relate to a range of social and political behaviors. I use focus

groups to draw out people’s thought processes when it comes to making sense of power and the possibility of conspiracy.

In this book, a conspiracy theory (or claim) is defined as a statement alleging that (1) a small number of actors (2) were or are acting covertly (3) to achieve some malevolent end. It must also (4) conflict with the most plausible explanation and (5) lack sufficient credible evidence.35 Conspiracy claims are not necessarily false. In recent history, some claims that were once considered conspiracy theories ultimately turned out to be true.36 The key is that credible evidence to support the claim must not have been available to the public or verified by reliable sources at the time.37

To see how this definition applies in practice, consider the example from Ukraine that opened this chapter. According to the Russian Foreign Ministry, (1) “external sponsors”—presumably the United States—brokered an agreement to end the standoff between the Yanukovych regime and the opposition (2) as a cover for its true aims: (3) overthrowing the government for geopolitical gain. This explanation differs from the official, and well-documented account, (4) that President Yanukovych fled after his security forces dissolved. Meanwhile, (5) no credible evidence was adduced (or has since surfaced) that the United States engineered his sudden ouster or masterminded the protests as a pretext to pull Ukraine out of Russia’s orbit.

Determining what should or should not count as a conspiracy claim requires special attention to context, especially when dealing with nondemocratic political systems. Some activities that would be considered conspiratorial in longstanding democracies may be widespread and well-documented in post-Soviet states, and so would not qualify. For example, an allegation that an incumbent president engages in election fraud would typically not be considered a conspiracy claim in these countries. Even the allegation that people associated with the Kremlin poisoned ex-spy Alexander Litvinenko with polonium in London is not a conspiracy theory. While unusual and sensational, there was substantial evidence implicating the Russian government and no similarly plausible account that exonerates it. On the other hand, the counterclaim that British intelligence poisoned Litvinenko to discredit Russia is a conspiracy theory because there is no evidence to support it.

A conspiracy theory must be politically significant in order to be included. Ordinary political “dirty tricks” like using deception or innuendo to outmaneuver an opponent usually will not qualify. The antics of private citizens, including businesspeople and journalists, do not count unless they have political implications. Criminal charges within the quotidian processes of the legal system are not conspiracy claims. Active conflict situations are excluded because they operate outside the bounds of conventional politics and are difficult to

adjudicate. Name-calling, hyperbole, mockery, character assassination, and lies may be unpleasant and intended to secure political advantage, but they are not conspiracy claims in and of themselves.

This book outlines a theory about the rhetoric of representatives of incumbent regimes, which I sometimes refer to as the “ruler” or “leader” as a shorthand term. Because a variety of actors may speak for the regime, including journalists and nominally independent experts, for the database I collected all conspiracy claims that appeared in selected sources on particular days, regardless of the accuser. Having access to the full range of claims is valuable for understanding the broader context, including identification of the allegations that officials are responding to and the ideas that are in circulation. This collection strategy privileges pro-regime communication because it is more likely than counterhegemonic discourse to be reported in available sources, especially where the media is state-controlled. Because of this bias, I present some analyses that encompass the various voices involved in political contestation, but I can confidently draw conclusions only about claims made by government officials and their proxies.

Because the database comprises conspiracy theories that appeared in newspapers or on television at selected times, it represents only a snapshot. It does not capture the broader political culture or popular sentiments about conspiracy, which may be transmitted orally or in venues apart from major media outlets. Insofar as officials endorse conspiracy theories, it is not always possible to trace their lineage—whether they are appropriated from oppositional actors, adapted from cultural tropes, or created out of whole cloth. So although I can investigate how claims are deployed within the surrounding political milieu, my data do not enable me to trace the origins of conspiracy theories or to document how they travel.

What Conspiracy Theories Mean

Politicians everywhere are known to shade the truth, put “spin” on inconvenient facts, and selectively highlight or ignore information intended for public consumption. Although conspiracy theories diverge from the ideal form of rhetoric as envisioned in democratic theory, they sit comfortably alongside other forms of distasteful political rhetoric. When used in small doses, and without targeting vulnerable groups, conspiracy theories may be fully compatible with democratic (or autocratic) politics as practiced in the real world. After all, nationalism is based on a conspiratorial logic pitting “us” against “them” yet is accepted as an inevitable—or even positive—feature of modern societies.38

However, the normalization of conspiracy theories in public discourse should also be seen as the canary in the democratic coal mine—a leading indicator of troubles ahead. A functioning democracy relies on shared recognition of facts, which enables parties and factions to debate issues of public concern, and empowers voters to hold their representatives accountable. When public officials habitually invoke conspiracies, then democracy may persist in form, but its quality will suffer.

In much of the democratic world, the long-term decline of trust in government and rising polarization provide new opportunities for entrepreneurs in politics, business, and the media to peddle their conspiratorial wares for commercial or political gain. It has also made these societies vulnerable to the spread of disinformation from state actors, such as Russia, that seek to deepen political divides. Judging by the rise of illiberal populism and concerted attacks on the notion of shared truth in democracies in the late 2010s, old distinctions between an “enlightened” West and a “backward” East may be wearing thin.39 The lessons from this book, which explain how conspiracy theories are used in a part of the world where democracy came late—or never arrived—can be instructive for concerned citizens everywhere.

What Lies Ahead

Revealing Schemes moves from general to specific themes, with the heart of the book consisting of paired chapters. Chapter 1 lays out an explanatory framework for making sense of the politics of conspiracy, while Chapter 2 seeks out the origins of conspiracism in the former Soviet Union. It outlines the region’s troubled historical development and examines challenges the region’s leaders have faced in more recent times.

The next four chapters draw from the database. Chapter 3 provides a descriptive overview of post-Soviet conspiracy theories and analyzes their narrative structure. Chapter 4 tests plausible hypotheses about the production and propagation of conspiracy claims. Chapters 5 and 6 examine the use of conspiracy claims in depth, beginning with the region’s main engine of conspiracy, Russia, followed by an analysis of four countries that represent diverse political systems and geopolitical alignments.

Chapters 7 and 8 investigate the effects of conspiracy theories. First, surveys reveal what people in Georgia and Kazakhstan believe, and how conspiracism shapes attitudes toward political authority. Then, I examine how individuals in focus groups weigh conspiracy claims and how they regard power more generally.

Chapter 9 concludes by discussing what this book contributes to scholarly research on regimes and propaganda and then looks beyond the post-Soviet region. It applies insights from earlier chapters to make sense of the increasingly conspiracist political discourse in Turkey and the United States, examines the global spread of conspiracy theories, and closes by discussing the implications of the preceding analysis for democracy and governance.