1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gopinath, Sumanth S. | Pwyll ap Siôn.

Title: Rethinking Reich / edited by Sumanth Gopinath and Pwyll ap Siôn.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018041188 | ISBN 9780190605285 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780190605292 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Reich, Steve, 1936—Criticism and interpretation. | Minimal music—History and criticism.

Classification: LCC ML410.R27 R47 2019 | DDC 780.92—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018041188

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Paperback printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

Hardback printed by Bridgeport National Bindery, Inc., United States of America

To Beth and Nia, and dedicated to John Thomas Becker (1986–2017) and Dafydd Tomos Dafis (1958–2017)—two close friends who were also very talented musicians. They will be missed.

Acknowledgments

Copyright Permissions

List of Contributors

Introduction: Reich in Context 1

Sumanth Gopinath and Pwyll ap Siôn

I Political, Aesthetic, and Analytical Concerns

1 “Departing to Other Spheres”: Psychedelic Science Fiction, Perspectival Embodiment, and the Hermeneutics of Steve Reich’s Four Organs 19 Sumanth Gopinath

2 “Moving Forward, Looking Back”: Resulting Patterns, Extended Melodies, Eight Lines, and the influence of the West on Steve Reich 53 Pwyll ap Siôn

3 Different Tracks: Narrative Sequence, Harmonic (Dis)continuity, and Structural Organization in Steve Reich’s Different Trains and The Cave 75 Maarten Beirens

4 “We Are Not Trying to Make a Political Piece”: The Reconciliatory Aesthetic of Steve Reich and Beryl Korot’s The Cave 93 Ryan Ebright

II Repetition, Speech, and Identity

5 Repetition, Speech, and Authority in Steve Reich’s “Jewish” Music 113 Robert Fink

6 Steve Reich’s Dramatic Sound Collage for the Harlem Six: Toward a Prehistory of Come Out 139 John Pymm

7. From World War II to the “War on Terror”: An Examination of Steve Reich’s “Docu-Music” Approach in WTC 9/11 159

Celia Casey

III Reich Revisited: Sketch Studies

8 “Save as . . . »”: Hybrid Resources in the Steve Reich Collection 179

Matthias Kassel

9 Sketching a New Tonality: A Preliminary Assessment of Steve Reich’s Sketches for Music for 18 Musicians in Telling the Story of This Work’s Approach to Tonality 191

Keith Potter

10 Improvisation, Two Variations on a Watermelon, and a New Timeline for Piano Phase 217

David Chapman

11 Steve Reich’s Counterpoints and Computers: Rethinking the 1980s 239

Twila Bakker

IV Beyond the West: Africa and Asia

12 Afro-Electric Counterpoint 259

Martin Scherzinger

13 That’s All It Does: Steve Reich and Balinese Gamelan

Michael Tenzer

14 “Machine Fantasies into Human Events”: Reich and Technology in the 1970s

Kerry O’Brien

Acknowledgments

The two editors of this volume would like to thank the following:

The Paul Sacher Stiftung, Basel, and all the scholars and staff there, especially Matthias Kassel (curator of the Steve Reich collection), Tina Kilvio Tüscher, and Isolde Degen; Oxford University Press, especially Suzanne Ryan, who provided much-needed guidance, advice, and encouragement from our initial, tentative proposals to the final publication; also Vika Kouznetsov, Lauralee Yeary, Jamie Kim, Adam Cohen, Dan Gibney, Eden Piacitelli and all those at Oxford University Press who have assisted with copyediting and indexing; Christina Nisha Paul (Project Manager for Newgen Knowledge Works), Sangeetha Vishwanthan, Susan Ecklund, and Pilar Wyman; Janis Susskind, Mike Williams and Tyler Rubin at Boosey & Hawkes; Katie Havelock and Matthew Rankin at Nonesuch Records; Livia Necasova at Universal Edition; Philip Rupprecht, Laura Tunbridge, and Marianne Wheeldon, as editors of previous volumes in the Rethinking series for readily sharing valuable advice; Lynda Corey Claassen (Director of Special Collections & Archives at UC San Diego Library), Shelley Freeman; Josh Rutter for his willingness to participate in this project and his contributions to it.

The editors also wish to thank all the contributors to this volume for their willingness to respond to requests for changes, corrections and additions; and for their patience throughout the publication process.

Sumanth Gopinath wishes to thank friends and family, especially his partner Beth, his parents, Sudhir and Madhura, and his brother, Shamin, for their unwavering support and love; Pat McCreless, Michael Veal, Michael Denning, Hazel Carby, Paul Gilroy, Robert Morgan, Jim Hepokoski, John MacKay, Greg Dubinsky, Michael Friedmann, Matthew Suttor, and other faculty members who were important influences on his work on Reich while in graduate school; Beth Hartman, Robert Adlington, Jonathan Bernard, Trevor Bača, Seth Brodsky, Thomas Campbell, Michael Cherlin, Eva R. Cohen, James Dillon, Eric Drott, Gabrielle Gopinath, Ted Gordon, Russell Hartenberger, Michael Klein, Matthew McDonald, Leta Miller, Ian Quinn, Rob Slifkin, Jason Stanyek, Vic Szabo, his co-editor and all of the contributors to this volume, all graduate students participating in his “Musical Minimalisms” seminar between 2005 and 2018, his colleagues in the music theory division (Matt Bribitzer-Stull, David Damschroder, and Bruce Quaglia) and School of Music at the University of Minnesota, and many other interlocutors on Reich and minimalism over

the years, for their innumerable insights; the Paul Sacher Stiftung, Basel, for a fellowship to study there for a month in August 2015; and the University of Minnesota, for a research grant from the Imagine Fund.

Pwyll ap Siôn wishes to thank friends and family, especially his partner Nia; his parents Morwen and John; Tomos and Osian, staff and colleagues at the School of Music, Bangor University; doctoral students who helped in various ways with this publication, especially Twila Bakker and Tristian Evans; Bangor University for granting a period of research leave during 2015–16; the British Academy for the award of a Small Research Grant in 2014–15 to visit the Paul Sacher Stiftung, Basel; the Leverhulme Trust for the award of a Research Fellowship in 2016–17 to carry out further research on the music of Steve Reich, especially Anna Grundy; Nikki Morgan and Martin Rigby for providing English translations to German texts; Rafael Prado and the Fundación BBVA in Madrid; and belated thanks to Bryony Dawkes for the Grainger excerpts.

Copyright Permissions

The following figures, tables and examples have been reproduced with kind permission from the Steve Reich Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation (PSS), Basel

Figure 1.1 An approximate transcription of Reich’s sketchbook doodle, August 14, 1969, Sketchbook [1]

Table 3.1 List of harmonies attributed to each scene of act 2 of The Cave, transcribed from the composer’s Sketchbook [42].

Example 3.1 Speech melodies in The Cave from the first Hagar scene, act 1 (1993 version).

Example 3.2 Sample and harmonies from The Cave, act 1 (“Isaac” scene) as notated in Reich’s sketchbook, Sketchbook [41].

Example 4.1 Transcription of entry dated July 22, 1990, in Sketchbook [41].

Table 4.2 Fragment from “Abraham & Nimrod” computer document.

Table 6.1 Arrangement of tape transcription, sourced from SR CD-3 Track 5 entitled Harlem’s Six Condemned.

Table 7.1 Steve Reich’s list of interview questions for WTC 9/11 (2010).

Example 7.1 Compositional sketch dated “7/28/10”.

Figure 8.1 Steve Reich, Different Trains (1988), screenshot of the folder structure in list form.

Figure 8.2 Steve Reich, Different Trains (1988), screenshot of the folder structure in expanded list form.

Example 9.1 February 1, 1989: untitled sketch for Music for 18 Musicians, recopying of “cycle of 11 chords,” dated “2/1/89,” Sketchbook [39], whole page.

Example 9.2 February 20, 1975: “Work in Progress for . . . 18 Musicians,” ten pulsing chords, treble only, dated “2/20/75,” Sketchbook [15], first two staves only.

Example 9.3 March 14, 1975: “Opening Pulse—revision & expansion,” dated “March 14,” Sketchbook [15].

Example 9.4 April 28, 1974: untitled sketch for pulse and oscillating chords, dated “4/28” Sketchbook [13] whole page.

xi

Copyright Permissions

Example 9.5 December 4, 1974: untitled sketch for a sequence of four-part chords, on page dated both “12/2” and “12/4” Sketchbook [14] whole page.

Example 10.2 Transcribed selection from Reich’s first Variation on a Watermelon (digitized archival recording of March 19, 1967 performance at Park Place Gallery).

Table 10.3 Fairleigh-Dickinson University Program, January 5, 1967, in folder “Programme Jan 1967”.

Chapter 10, Appendix 1 Transcription of the March 1967 Performance of the second Variation on a Watermelon (digitized archival recording of March 19, 1967 performance at Park Place Gallery).

Chapter 10, Appendix 2 The Piano Phase improvisation, January 1967 (digitized archival recording of January 5, 1967, performance at Fairleigh-Dickinson University Art Gallery).

Table 11.2 Comparison of select early Electric Counterpoint computer files.

Figure 12.1 Reich’s sketch for Clapping Music and Music for Pieces of Wood

Example 12.12 Transcription of Reich’s final sketch for Electric Counterpoint.

Table 13.1 List of recordings of Balinese gamelan in Reich’s collection.

Example 14.1 Reich’s Four Log Drums, mm. 4–5.

Example 14.2 Music for 18 Musicians manuscript [2/10], p. 1, mm. 1–8.

Example 14.3 Music for 18 Musicians manuscript [2/10], p. 84, mm. 577–82.

All text references, transcriptions of (or from) interviews taken from sources kept at the Steve Reich Collection, including the composer’s own comments and/or annotations, have been used with permission from the Paul Sacher Foundation.

Copyright permissions from other sources:

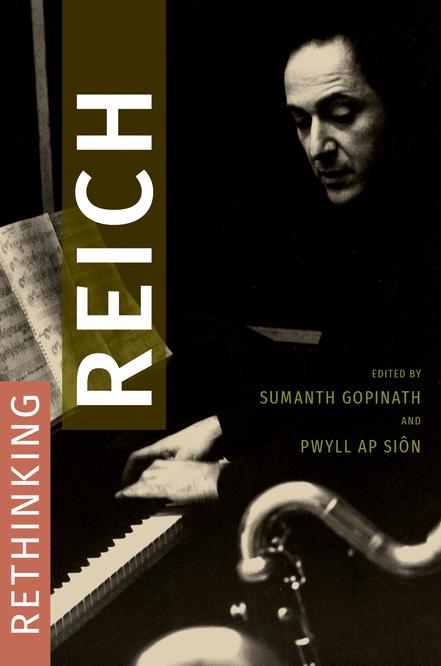

Front Cover: Steve Reich during a rehearsal of Music for 18 Musicians, New York, March 1976. Photograph by Betty Freeman © Copyright Shelley Freeman (with thanks to Lynda Corey Claassen, Director of Special Collections & Archives, Mandeville Special Collections, UC San Diego Library, and Matthias Kassel at the Paul Sacher Stiftung).

Example 1.4 Reduction of Four Organs, m. 11. © Copyright 1980 by Universal Edition (London) Ltd., London/UE16183. Reproduced by permission.

Example 2.2 Flute melody and piano 1 part in Eight Lines, rehearsal 74A © Copyright 1980 Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes company. Reproduced by permission of Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd.

Copyright Permissions xiii

Example 2.4 Extended melody in flute in opening section of Eight Lines, rehearsal 11. © Copyright 1980 Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes company. Reproduced by permission of Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd.

Example 5.1 Reich, The Cave, act 1, scene 1, mm. 10–30. The Cave by Steve Reich and Beryl Korot © Copyright 1993 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes company. Reproduced by permission of Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd.

Example 5.2 Reich, The Cave, act 1, scene 7, mm. 1–16. The Cave by Steve Reich and Beryl Korot © Copyright 1993 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes company. Reproduced by permission of Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd.

Figure 10.1 Reich demonstrating the “stacked-hand” disposition in Piano Phase (source: Steve Reich: Phase to Face, dir. Éric Darmon and Frank Mallet). Illustration by Stephanie Fitzgerald. Used with permission.

Figure 14.1 Four Log Drums at the Whitney Museum of American Art (May 27, 1969). Photograph © Richard Landry

Figure 14.2 An image from the documentary Wasserpfeifen in New York: Musikalische Avantgarde zwischen Ideologie und Elektronik [45:46] (reproduced in New Music: Sounds and Voices from the Avant-Garde [44:32]). © Michael Blackwood Productions Inc.

The format for indicating minutes and seconds in this volume is as follows: 04:33

Contributors

Pwyll ap Siôn is Professor of Music at Bangor University, Wales. His publications include The Music of Michael Nyman (2007) and Michael Nyman: Collected Writings. He coedited The Ashgate Research Companion to Minimalist and Postminimalist Music (2013) with Keith Potter and Kyle Gann, and has contributed articles and reviews to Contemporary Music Review, TwentiethCentury Music, and Performance Practice Review. In 2016, he received a Leverhulme Research Fellowship to focus on the music of Steve Reich. He also contributes regularly to Gramophone music magazine.

Twila Bakker completed her doctorate in musicology at Bangor University, Wales, in 2016, focusing on Steve Reich’s Counterpoint pieces. Her current research, supported by a 2018 Paul Sacher Foundation research grant, addresses digital sketch studies utilizing Reich’s compositional output as a case study. Bakker is a committee member of the Society for Minimalist Music and holds previous degrees in music and history from the University of Victoria and the University of Alberta, Canada.

Maarten Beirens studied musicology at the Catholic University of Leuven (KU Leuven), Belgium, where he was awarded a PhD in 2005 for his thesis on European minimal music. He then held a postdoctoral fellowship awarded by FWO Flanders at KU Leuven, conducting research on the music of Steve Reich, before being appointed lecturer in musicology at the University of Amsterdam. He contributed a chapter to The Ashgate Research Companion to Minimalist and Postminimalist Music (2013). Other publications have appeared in the Revue Belge de Musicologie, Tempo, and Contemporary Music Review.

Celia Casey submitted her doctorate in musicology at the University of Queensland, Australia, in 2018, researching the creative process in Steve Reich’s speech works. Prior to this, her first-class honors thesis investigated aspects of Erik Satie’s contribution to conceptual art. Her research has benefited from interviews with Reich and from the support of a Paul Sacher Foundation research grant and travel awards from the University of Queensland, allowing several visits to the Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel, to undertake sketch studies. She has performed widely as a cellist and vocalist and is currently employed by the Queensland Symphony Orchestra.

David Chapman is Assistant Professor of Music at Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology in Terre Haute, Indiana, where he teaches music history and theory to engineers, mathematicians, and scientists. His research focuses primarily

on the role of performance, improvisation, and ensembles in the downtown New York avant-garde music scene of the 1960s and 1970s. He holds degrees in piano performance and in musicology from Kennesaw State University, Georgia, and the University of Georgia, respectively. He received his PhD from Washington University in St. Louis in 2013 for a thesis on Philip Glass and the downtown New York scene between 1966 and 1976.

Ryan Ebright serves as an Instructor of Musicology at Bowling Green State University. He earned his PhD in musicology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2014 and holds a masters’ degree in musicology and vocal performance from the Peabody Conservatory. His research includes music for the voice, stage, and screen, with an emphasis on contemporary opera, minimalism, and nineteenth-century lieder, and has been published in American Music, Notes, and the online publication on contemporary music NewMusicBox.

Robert Fink is Professor of Musicology at the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music and author of Repeating Ourselves: American Minimal Music as Cultural Practice (2005). His publications on minimalism and repetition, popular music, the fate of the classical canon, and problems of musical analysis have appeared in Rethinking Music (1999), Beyond Structural Listening? (2004), and The Ashgate Research Companion to Minimalist and Postminimalist Music (2013), and in journals including Cambridge Opera Journal, Journal of the American Musicological Society, and American Music. Along with Cecilia Sun, he is the collator of Oxford Bibliographies Online’s substantial entry on “Minimalism.”

Sumanth Gopinath is Associate Professor of Music Theory at the University of Minnesota. He is the author of The Ringtone Dialectic: Economy and Cultural Form (2013) and coeditor, with Jason Stanyek, of The Oxford Handbook of Mobile Music Studies (2014). His research ranges widely from Steve Reich and musical minimalism to Marxism and music scholarship, sound and digital media, Bob Dylan, Benjamin Britten, the aesthetics of smoothness, and the music of contemporary Scottish composer James Dillon.

Matthias Kassel studied musicology and German language and literature in Freiburg im Breisgau. He has been a curator at the Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel, since 1995. His publications and articles focus mainly on composers’ collections in the archive. Recent interests include the work of Mauricio Kagel, and the Steve Reich collection, as well as the performance practice and archival aspects of new music.

Kerry O’Brien is an Instructor at the Cornish College of the Arts, Seattle. She received her PhD from Indiana University in 2018, having written a dissertation on the history of the arts organization Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), 1966–1971, which includes a chapter on Steve Reich. Her work on postwar experimentalism, minimalism, and countercultural spirituality has

been supported by a Presser Music Award, a Paul Sacher Foundation research grant, a Getty research library grant, and an American Fellowship from the American Association of University Women. Her research has been published in the Mitteilungen der Paul Sacher Stiftung and NewMusicBox, and in articles in the New York Times and the New Yorker online.

Keith Potter is Professor of Music at Goldsmiths, University of London. Active as both musicologist and music journalist, he was for many years chief editor of Contact: A Journal of Contemporary Music, the thirty-four issues of which will be republished online in 2019. For a decade, he was a regular music critic for The Independent daily newspaper. A founding committee member of the Society for Minimalist Music, he was its Chair from 2011 to 2013. His publications include Four Musical Minimalists: La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass (2000) and The Ashgate Research Companion to Minimalist and Postminimalist Music (2013), coedited with Kyle Gann and Pwyll ap Siôn. Recent publications on Reich, arising from research carried out at the Steve Reich archive at the Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel, have appeared in Tonality since 1950 (2017) and Contemporary Music Review (2018); and the outcome of collaborative projects on musical perception and cognition, involving music by Glass as well as Reich, appeared in Music and/as Process (2016) and the journal Time and Time Perception.

John Pymm is Dean of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Wolverhampton. He is a founding member of the Society for Minimalist Music and was elected three times as the Society’s President between 2013 and 2017. He has given numerous international conference papers on the music of Steve Reich, based on archival research carried out at the Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel, contributing a chapter to The Ashgate Research Companion to Minimalist and Postminimalist Music (2013). He received his PhD from the University of Southampton in 2013.

Martin Scherzinger is Associate Professor of Media, Culture and Communication at New York University. His research focuses on the relationship between sound, music, media, and politics, and his work has appeared in publications including Postmodern Music/Postmodern Thought (2002), Beyond Structural Listening? (2004), and The World of South African Music: A Reader (2005) and in the journals Current Musicology, Perspectives of New Music, and Cultural Critique

Michael Tenzer is a performer, composer, scholar, and teacher. He has been active in the international proliferation of gamelan music since 1977, undertaking years of fieldwork in Indonesia and cofounding Gamelan Sekar Jaya in Berkeley in 1979. He was the first non-Balinese composer to create new works for Balinese ensembles in Bali. His book Gamelan Gong Kebyar: The Art of Twentieth Century Balinese Music (2000) received the Alan P. Merriam Prize of the Society for Ethnomusicology and the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award. He has a PhD in music composition from UC Berkeley and has been Professor of Music at the University of British Columbia since 1996.

Rethinking Reich

Introduction

Reich in Context

Sumanth Gopinath and Pwyll ap Siôn

Now we were home again, sitting among the colors of the living room. I started to put Van Morrison on, and she said, “Hey, have you ever heard Steve Reich?”

I told her no. I told her I’d been living outside the music zone, catching whatever happened to blow through. She said, “I’m going to put him on right now.” And she did.

Steve Reich’s music proved to be a pulse, with tiny variations. It was the kind of electronic music that doesn’t come from instruments—that seems made up of freeze-dried interludes of vibrating air. Steve Reich was like someone serenely stuttering, never getting the first word out and not caring if he did. You had to work to get the point of him, but then you got it and saw the simple beauty of what he was doing—the lovely unhurried sameness of it. It reminded me of my adult days in Cleveland, those little variations laid over an ancient luxury of replication.1

The narrator in this passage from Michael Cunningham’s novel A Home at the End of the World (1990) is Bobby Morrow, a young baker from Cleveland. Bobby has recently moved in with Jonathan Glover, his gay childhood friend, and Jonathan’s female roommate, Claire, who are living in the East Village in Manhattan during the early 1980s—“the dead center of the Reagan years.”2

A knowledgeable and passionate rock listener, Bobby is soon introduced to Reich’s music by Claire, who provides him with a cultural education and, eventually, a sexual one. The eventual outcome is an asymmetrical, bisexual ménage à trois between the three main characters and the resulting, unconventional family household, which devolves by the end of the novel.

Music was central to the novel’s creation, and rock songs and references to them are threaded through it, performing a certain affective immediacy. For Cunningham, rock music “insists that our loneliness and confusion, our wild nights and our love affairs gone wrong, are significant subjects, worthy of guitar riffs and drum solos. As a writer, I’ve tried to put a measure of that reckless generosity onto the printed page.”3 Reich’s music is, in contrast, not as self-evident to its fictional listeners, for one had to “work to get the point.” The music is not

only reminiscent of Bobby’s inertial existence in Cleveland; it is also a part of his makeover by Claire into a cosmopolitan New Yorker. In the novel, Reich effectively acts as a sign within a tiny community, a pair of downtown Manhattanites on the margins of art worlds—Jonathan is a food critic for a successful weekly news publication, Claire is a trust-funded bohemian jeweler and was formerly married to a touring dancer. Their tastes crisscross the brow spectrum: in addition to being music aficionados, they attend parties, plays, and especially film screenings at various theaters, and they frequent dive bars and hole-in-the-wall restaurants (because of Jonathan’s work) and watch TV together, when Jonathan isn’t seeing his lover, Erich. Reich’s music accompanies many other cultural products and forms that bind Bobby to this new household, the wider milieu of downtown Manhattan, and, ultimately, the familial arrangement between the three characters that will soon emerge—three interconnected characters raising a baby in remote, symbolically-charged Woodstock.

Music scholars may well wonder which Reich piece is being referenced here. The description “a pulse, with tiny variations” recalls the opening and closing “Pulses” sections of Music for 18 Musicians (1976). The 1978 ECM LP recording of that piece famously sold more than one hundred thousand copies within a year of its release, making this crossover hit the most likely possibility. And yet, the descriptions of the music as “electronic [sic]” and the composer as “serenely stuttering” are perhaps more reminiscent of Reich’s tape pieces It’s Gonna Rain (1965) and especially Come Out (1966), both released on LP by Columbia in the late 1960s, and also of their “sampling” techniques to which Reich would return later that decade, beginning with Different Trains (1988).4

But perhaps the most telling word in Cunningham’s description is one of the most banal: “variations.” The term is a marker of what one might think of as Reich’s turn toward more conventional forms and musical forces (commissioned solo compositions, works for full orchestra, choral pieces). It first appears in Variations for Winds, Strings, and Keyboards (1979) and then resurfaces in a trio of post–video opera compositions written in the first decade of the twentieth century: You Are (Variations) (2004), Variations for Vibes, Pianos and Strings (2005), and the Daniel Variations (2006). While Cunningham’s description— “little variations laid over an ancient luxury of replication”—might sound like a characterization of music with a more ambient sensibility than Reich’s, “variations” indexes a more traditional temporality, of longer phrases and lines that are then subjected to transformation, perhaps in the manner of a theme and variations.5 Reading against the grain of Cunningham’s rock-based understanding of Reich, we can appreciate that a new traditionalism emerges with the onset of this period of the composer’s music, including the composer’s own rediscovery of text-setting and extended melodic composition in Tehillim (1981). That traditionalism resonates with his own description of the “conservative 1980s,” to which he bade farewell by the end of the decade and to which he seemingly returned after his last video opera with Beryl Korot, Three Tales (2002).6

In retrospect, what we might call Reich’s “long 1980s”—beginning in the late 1970s, after his post–Music for 18 Musicians crisis, when he considered giving up composition and becoming a rabbi7 launched him on a path toward legitimacy in the world of mainstream classical music. Indeed, it was during the “dead center” of the Reagan/Thatcher era that Reich firmly established himself as one of the most important composers of the late twentieth century. Claims such as “America’s greatest living composer,” or accolades that placed him as one of “a handful of living composers who can legitimately claim to have altered the direction of musical history,”8 were still some way off (after all, Reich would only turn fifty during the decade), but his music was spreading much farther outside rather than within degree programs in music departments and schools, where undergraduates’ staple diet of the Three Bs (and the canon more broadly) would be supplemented by contemporary modernist music—Berio, Boulez, Babbitt, or Birtwistle, perhaps. In fact, one was more likely to hear strains of Music for 18 Musicians or Tehillim emerging from the room of a philosophy, art history, or English literature student—a relaxing sonic technology of the self-applied long after the day’s classes had finished, and not as the object of analytical or historical study within the classroom.

Even during the 1980s, Reich’s music was still only grudgingly accepted by many members of the music “establishment.” Other than the ubiquitous Clapping Music (1972), or occasionally Music for Pieces of Wood (1973), which also required limited instrumental resources, his music remained rarely performed. One usually had to get to New York or London to hear performances of true quality, or hope that the composer and his ensemble would make a rare visit to town, which was, of course, more likely in the United States. Even performers of contemporary repertoire were reluctant to embrace his music, put off perhaps by its rhythmic demands and austere aesthetic challenges.

There were even slimmer pickings for those who wished to research it.

A stubborn view remained that music of the so-called minimalist school of composers—into which Reich had been unwittingly (and unwillingly) coopted—resisted standard forms of analysis. After all, what hidden mysteries could be revealed in an aesthetic that was so self-reflexively transparent?

A music that, according to the composer himself, possessed no “secrets of structure that you can’t hear”?9 Of course, Reich’s music did, in fact, possess “secrets of structure,” as visibly demonstrated in Paul Epstein’s revelatory analysis of the phase relationships in the first section of Piano Phase, published in Musical Quarterly in 1986.10 K. Robert Schwarz’s nuanced two-part introduction to Reich had appeared in the pages of Perspectives of New Music some six years previously,11 followed a few years later by the English-language translation of Wim Mertens’s influential American Minimal Music: La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, 12 but on the whole it was left to music critics to weigh up the merits of Reich’s works in their weekly dispatches, where opinions veered from knowledgeable (Tom Johnson), supportive (Alan Rich), or both

(Kyle Gann), to dismissive and hostile (Donal Henahan, Harold C. Schonberg). No wonder Reich himself became deeply suspicious of critics and their motives.

Still, Epstein’s article opened the door for a generation of academics who were interested in studying Reich’s music. It also marked one of the first attempts to rethink the nature and scope of the composer’s oeuvre—to delve beneath its outer surface in order to examine and uncover what was going on underneath, or even to demonstrate that there was something underneath that surface to uncover in the first place. Other articles from around the same time, including Dan Warburton’s “A Working Terminology for Minimal Music,”13 added further weight to the argument that minimalist music deserved scholarly study, while others around this time looked to draw parallels between Reich’s music and broader concerns, such as Rob Cowan’s short but insightful article on Reich and Wittgenstein.14

It was only during the 1990s that minimalist musicology in general, and Reich’s music in particular, fully gathered pace, however. Publications proliferated as the decade (and century) drew to a close, and during the intervening years the scope of Reich studies has extended to include everything from beat-class set and information-dynamic analysis to race, gender, desire creation, and mood regulation.15 Out of this welter of scholarly activity three main strands have emerged. The first remains more consolidatory in approach, building and developing on primary research conducted throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Edward Strickland’s Minimalism:Origins, published in 1993, was the first in-depth account of the movement in relation to both the fine arts and music. This was soon followed by K. Robert Schwarz’s Minimalists, which offered an extended treatment of Reich’s “minimalist” and “maximalist” periods. Keith Potter’s Four Musical Minimalists: La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, 16 published in 2000, bore the fruits of more than twenty years of dedicated and detailed research, immediately establishing itself as the area’s authoritative textbook. The second strand treats minimalist music, including Reich’s, as a topic of involved analytical and theoretical study, often drawing on various forms of mathematics and examining rhythmic-structural features of which the composer himself was almost certainly unaware. This was the argument of Richard Cohn in his pathbreaking essay, “Transpositional Combination of Beat-Class Sets in Steve Reich’s Phase-Shifting Music” (1992).17 In contrast to the previous two strands, the third drew inspiration from the “new musicology” of Susan McClary, Ruth Solie, Lawrence Kramer, and others. Like the second strand, it sought to understand Reich’s music less, perhaps, in relation to what the composer was stating, but unlike both other strands, it prioritized the rich layers of meaning and signifying potential the composer’s music offers to interested listeners.

One early example of the third scholarly tendency was Robert Fink’s “Going Flat: Post-hierarchical Music Theory and the Musical Surface,” which provided the would-be researcher with new tools for analyzing twentieth-century music, including minimalism. Like Epstein some ten years previously, Fink also looked

to Piano Phase. However, this time the piece was used to support an argument that revolved around questions relating to the relevance and usefulness of established analytical methods, with their emphasis on hierarchical structures, linear descents, levels of contrapuntal stratification, and implied distinction between surface and depth. Such methods did not hold sway when it came to analyzing minimalist works like Reich’s piece, which served as an object lesson on the problem of musical analysis in general: “The virtual coincidence of background and foreground progressions makes the voice-leading structure of Piano Phase almost totally non-hierarchic, totally flat. The backdrop has become the curtain.”18

Fink’s “Going Flat” appeared in Nicholas Cook and Mark Everist’s edited volume, Rethinking Music, which could be said to have set in motion Oxford University Press’s “rethinking” quasi-series. Whether stated or implied, much of what is contained in this latest collection in the series is informed by developments in musicology that took place around this time. By the early twenty-first century, the rate of productivity in Reich studies merited a biobibliography by David J. Hoek (2002), which included an annotated list of publications in English, French, German, and Italian. Hoek’s book certainly offered an important snapshot of the then current state of research on Reich, but one imagines that it would now be at least twice its original size were it updated to include research completed in the following seventeen years, from doctoral dissertations to journal articles, many of which appear in the works cited at the end of this volume. However, pace the composer’s own Writings on Music, 1965–2000, edited by Paul Hillier, only one book-length account focusing entirely on Reich’s music has been produced to date.19 This volume attempts to redress this imbalance.

It remains true that practice often precedes theory, and musicology represents only one area where Reich’s music has been rethought, reappraised, and reinterpreted. True, his music has always connected beyond the concert hall and lecture theater, but few would have predicted back in the 1970s or 1980s the extent to which it has penetrated aspects of today’s media and popular culture. Reich is now frequently heard on television and film, in dramatic contexts and situations that might shock and intrigue the composer and regular listeners of his music.20 To take three examples, we first return to the Cunningham passage discussed earlier, but as it appears in the 2004 film version of A Home at the End of the World. In the film, Claire (played by Robin Wright) puts on the Reich recording, and she and Bobby (Colin Farrell) hear section VI of Music for 18 Musicians. After about ten seconds of a medium close-up shot of Bobby reacting to the music, the film dissolves to another scene in which Jonathan (Dallas Roberts) is walking home, on the sidewalk. He passes a man who is walking his dog, and both cross in front of a third man sitting on a stoop. The two walking men make measured, balletic turns back toward each other and stare—they are checking each other out—while the seated man watches Jonathan. Having transformed from diegetic to nondiegetic music, the pulsating