PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION

This is the third edition of Resource and Environmental Management. The second edition was also translated and published in three other languages: Chinese, Indonesian, and Spanish. There has been a significant gap of time between the second and third editions, primarily because for 15 years I held several senior management positions at the University of Waterloo and was unable to find time to work on the next edition, even though encouragement was received to do so.

The third edition has the normal updates associated with a new edition, but in addition are other more substantial changes, including:

(1) Restructuring: The second edition contained 14 chapters; the third edition contains 12 chapters as a result of combining or restructuring some chapters from the previous edition.

(2) New material: While the new edition addresses the four concepts (change, complexity, uncertainty, conflict) that were the base of the second edition, it also gives explicit attention to ambiguity and wicked problems throughout the book. In addition, other new content includes consideration of social-ecological systems, the Anthropocene, and tipping points (chapter 1); weak and strong sustainability, and resilience (chapter 2); the rule of hand and the water–energy–food–health nexus (chapter 3); bridging organizations (chapter 4); evolutionary, passive, and active adaptive environmental management (chapter 5); the distinction between participation and engagement related to stakeholders (chapter 6); benefit-cost analysis, ISO 14001 (chapter 8); the triple bottom line, circular economy, industrial ecology, material flow cost accounting, emergy analysis, and corporate social responsibility (chapter 9); geomatics (chapter 11); and ethical issues, greenwashing, greenlashing, shaming campaigns, and leadership and followership (chapter 12). Furthermore, new examples from developed and developing nations have been incorporated into every chapter. Finally, each chapter opens with a set of itemized objectives, and ends with critical thinking questions. The latter are intended to encourage you to reflect upon what you learned from that chapter, and to consider the implications for resource and environmental management in specific situations.

(3) Guest statements: As in the second edition, the third edition includes a guest statement in every chapter, written by individuals from various countries and disciplines. The intent is for their perspectives and experiences to add additional

insights for the reader to reflect upon. In the third edition all of the guest statements—referred to in the book as “visions from the field”—are new, and all but one of the contributors also are new. The guest statement authors are from Australia, Canada, China, Germany, Hong Kong, Indonesia, the Netherlands, Singapore, Swaziland, United Kingdom, and the United States.

(4) References and further readings: For each chapter, many new sources have been drawn upon and are provided. In addition, for each chapter a set of updated further readings is provided.

(5) Glossary: A new feature in the third edition is a glossary, provided as an easy way to check on the meaning or intent of key concepts in the book. Words Bold in the text have definitions provided in the glossary.

In terms of acknowledgments, I am deeply grateful to all of the authors of guest statements. Each contributor was provided with a draft version of the chapter for which he or she had been invited to write a statement, as well as an explanation of the overall goals and objectives of the book. Each was asked to share one or more core messages, and, ideally, to illustrate those with one or more practical examples or experiences. Every individual invited to prepare a guest statement agreed to do so, and each person worked diligently to share insights from their experience, which range across numerous continents and countries, as well as reflecting views based on work experience in government departments, nongovernmental organizations, the private sector, and universities.

I have been learning continuously related to resource and environmental management. In that regard, in addition to the guest statement authors, I express my appreciation to Peter Adeniyi, Derek Armitage, Tim Babcock, Jim Bauer, Jim Bruce, Ryan Bullock, John Burton, John Chapman, Jack Craig, Rob de Loë, Phil Dearden, Alan Diduck, Tony Dorcey, Dianne Draper, O. P. Dwivedi, Paul Eagles, Trish Fitzpatrick, Graham Forbes, Yong Geng, Len Gertler, Bob Gibson, Stan Gregory, Wei Guo, Haryadi, Malcolm Hollick, Bruce Hooper, Bob Humphries, David Kinnersley, Ralph Krueger, Shuheng Li, Abdul Manan, Sugeng Martopo, Mary Louise McAllister, Dan McCarthy, Adrian McDonald, Geoff McDonald, Ali Memon, Thom Meredith, George Mulamoottil, Gordon Nelson, Baharuddin Nurkin, Greg Oliver, Paul Parker, John Pigram, George Priddle, Frank Quinn, A. Ramesh, Maureen Reed, Achmad Rizal, Sally Robinson, Ian Rowlands, Rodger Schwass, Derrick Sewell, Dan Shrubsole, Ted Simpson, John Sinclair, Scott Slocombe, Chui-Ling Tam, Baleshwar Thakur, Don Thompson, Mike Troughton, Barbara Veale, Ray Wallis, Ying Wang, Chris Wilkinson, David Wood, Bing Xue, Taiyang Zhong, and Xinqing Zou.

In addition to the above individuals, I am very appreciative of the comments and suggestions provided by three anonymous reviewers who Oxford University Press arranged to have review the draft manuscript of the third edition. They each provided helpful and constructive comments, which most certainly have improved the quality of this edition.

I also am grateful for technical support by Amanda McKenzie, a colleague at the University of Waterloo. She was always available with constructive and helpful advice. In addition, Ellsworth LeDrew digitized slides taken by me which appear in this book, for which I am most grateful.

Initial support was provided from individuals at the Oxford University Press office in Don Mills, Ontario. I am particularly grateful to Caroline Starr, associate acquisitions editor, who raised the idea of a new edition to be published by OUP; to Jodi Lewchuk, acquisition editor, who worked diligently to facilitate OUP to be able to publish the third edition; and to Peter Chambers, who worked with me throughout the process of preparing the manuscript. The Oxford University Press office in New York was responsible for

facilitating publication of the book, and I am grateful to colleagues there for their guidance and assistance during the stages of copyediting and development of page proofs. In particular, I am grateful to Jeremy Lewis, Senior Editor, in the New York office, who was the lead person throughout the publication process. In addition, I very much appreciate the support provided by Anna Langley, Assistant Editor in the New York office, Aishwarya Krishnamoorthy, Project Manager at Newgen Knowledge Works, who coordinated copy editing and page proof production, and Anne Sanow, who did the copy editing which significantly improved the overall quality of the book.

As with each book that I have written or edited, I gratefully express my appreciation to my wife, Joan, who has been a source of continuing support throughout my career. I have been truly blessed to have her as a companion in our shared life journey.

Bruce Mitchell

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

1. Understand the attributes of complex social and ecological systems, and their implications.

2. Appreciate the significance of the Anthropocene for resource and environmental management.

3. Understand the concepts of wicked problems, ambiguity, and tipping points, and their significance for resource and environmental management.

1.1 INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this chapter is to introduce selected key concepts that have major implications for resource and environmental management: complex social and ecological systems, the Anthropocene, wicked problems, ambiguity, and tipping points. The characteristics of each are described, and their significance explained. In addition, experiences from Tanzania, the Philippines, the United States, and India are presented to illustrate the importance of these concepts in practical resource and environmental management situations.

1.2 COMPLEX SOCIAL AND ECOLOGICAL SYSTEMS

In order to manage the environment and natural resource systems, it is vitally important to appreciate that we have to consider much more than the environment and natural resources. A key consideration is to recognize and appreciate that much of the change in natural ecosystems occurs because of interrelationships with humans. As a result, there is growing understanding that it is necessary to think in terms of social-ecological systems and their interactions. While that sounds logical and sensible, actually doing it can be challenging. To illustrate, what should be the scope and nature of the social and ecological systems to be considered, along with their interactions? Where do we begin to start understanding what are often termed complex adaptive systems, which are normally evolving and influenced by multiple and interacting forces? Given that our knowledge is often incomplete and even inaccurate, and that the predictive capacity of our models is often limited, how do we handle the nontrivial complexity and uncertainty associated with social-ecological systems? And, given that humans are not a homogeneous collective but

rather are heterogeneous, how do we identify, understand, and reconcile the diverse values, aspirations, motivations, preferences, and capacities of the many stakeholders, which often generate notable misunderstandings, mistrust, and conflicts? It is the purpose of this book to consider such matters, and help you to develop your capacity related to the environment and natural resource management.

The Serengeti National Park (SNP) in northwestern Tanzania illustrates the importance of and need to understand complex social-ecological systems, if appropriate planning and management decisions are to be taken.

Tanzania National Parks (http://www.tanzaniaparks.com/serengeti.html) states that the Serengeti National Park covers an area of 1.5 million hectares. The park, which includes grassland plains, savanna, forests, and woodlands, is a portion of a larger Serengeti ecosystem which extends into neighboring Kenya on its northern border. The SNP is listed as a world heritage site by UNESCO (http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/156). The park is part of the habitat through which annual migrations occur, covering about 1,000 km, by up to 2 million wildebeests and hundreds of thousands of Thomson gazelles and zebras, along with many others species, such as elephants and giraffes. At the peak of the migration, UNESCO has estimated that more than 8,000 wildebeest calves are born daily. Those migrations are tracked by predators such as lions, leopards, cheetas, jackals, and hyenas. What is considered to be one of the biggest annual and natural migrations of animals in the world also attracts thousands of tourists annually.

The Maasai people had grazed their animals on the Serengeti plains for hundreds of years before the first British explorers arrived in the late 1890s. In 1921, the British colonial administration created a partial game reserve of 3.2 km². The SNP was officially established in 1951, and during 1959 the British administrators evicted the Maasai from the park area, a decision that was controversial at the time and continues to be so today. The rationale for the eviction of the Maasai was to ensure the integrity of the Serengeti natural ecosystem. Over time, other adjacent game reserves and national reserves have been created to help protect the integrity of the contiguous Serengeti ecosystem. In 1981, the national park became part of a designated World Heritage Site and a biosphere reserve And in 2010, a debate began when President Kikwete of Tanzania announced construction of a road through the northern portion of the park, which would have divided the park into two halves. However, in June 2014 the East African Court ruled that the road works would be unlawful, and so it has not been built.

Nuno, Bunnefeld, and Milner-Gulland (2014) have used the SNP to examine both challenges and opportunities for successfully implementing conservation measures. They noted that human use of natural resources within the SNP has not been permitted since it was established as a national park. However, it is estimated about 2.3 million people live in districts adjacent to the SNP, and the population is growing at an annual rate of about 3 percent. As a result, conflicts exist over access to and use of land and natural resources in the area. As an example, bush meat hunting is regulated by the Tanzanian government, with hunters required to obtain hunting licenses that are allocated with reference to annual quotas. It is known that illegal hunting in the area is pervasive across the Serengeti ecosystem, as local people depend on bush meat for food.

With reference to the concept of complex social-ecological systems, it is not a surprise regarding what Nuno, Bunnefeld, and Milner-Gulland (2014) learned from a sample of respondents associated with four main organizations (Tanzania National Parks; Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute; the Gremeti Fund, a local NGO involved on one of the reserves; and Frankfurt Zoological Society), as well from collaborating university researchers, who all are responsible for making or influencing rules affecting bush meat

hunting in the Western Serengeti districts adjacent to the SNP. Their findings emphasize the interconnections between social and ecological systems, given that responses indicated the following as the three most significant threats to the SNP: increasing human population growth, land-use conflicts, and poaching. Other threats included climate change and associated environmental stresses; development, infrastructure, and tourism; poor management and governance; poverty and lack of opportunity; water scarcity and habitat degradation; invasive species; human-wildlife conflict; and mining. These perceived threats all can be characterized as on the social side of the social-ecological system that underlies the SNP, indicating the managers’ and planners’ need to address such interconnections. Given this significance, the next section focuses on the Anthropocene.

Further insight related to complex social and ecological systems is provided in the following guest statement by Rangarirai Taruvinga, who examines experience in Swazliand and highlights the considerable complexity and uncertainty often encountered, as well as the likelihood of encountering tipping points, a concept discussed later in this chapter.

VOICE FROM THE FIELD

Social-Ecological Complexity in Swaziland

Rangarirai Taruvinga, Swaziland

DEVELOPMENT CONTEXT

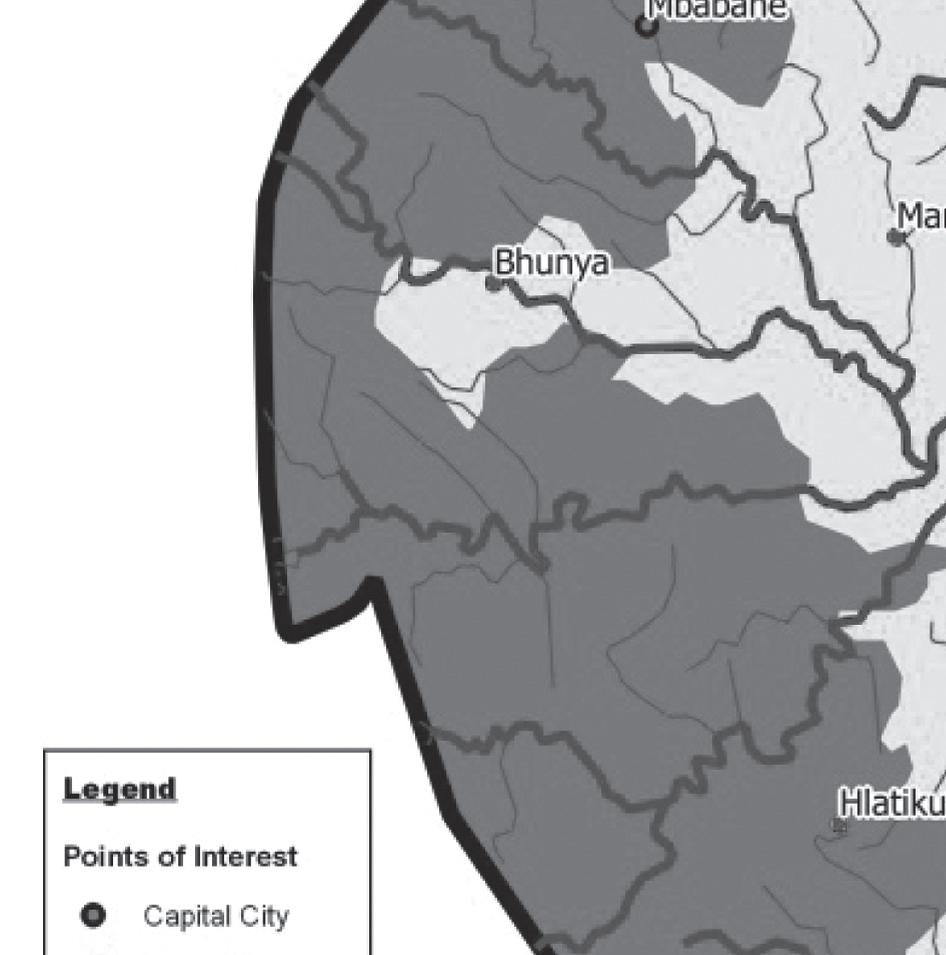

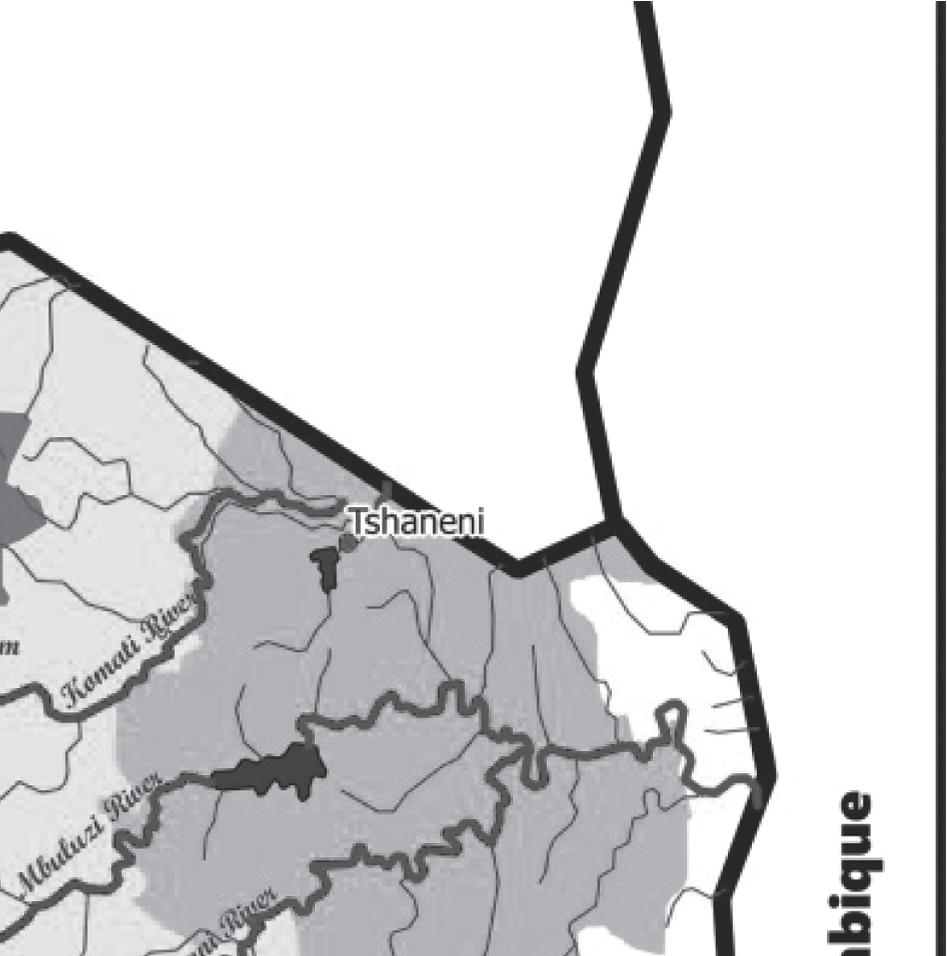

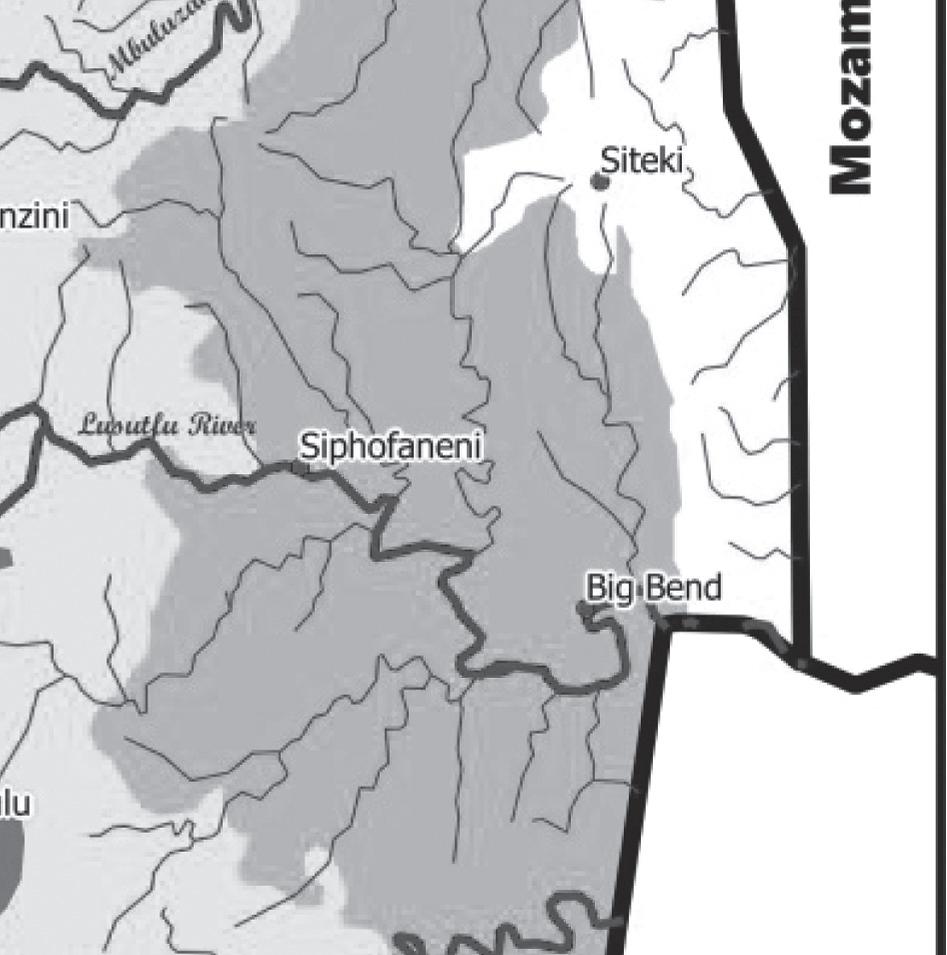

Swaziland covers about 17,000 square kilometres and is located in the southern part of Africa surrounded by Mozambique and South Africa (Figure 1.1). The population in 2016 was about 1.2 million. About 78 percent resides in rural areas (International Fund for Agricultural Development, 2010). Life expectancy was estimated at 49 years in 2009 (Life Management Online, 2018). In 2016, Swaziland had the highest prevalence

Photo by R. Taruvinga

of HIV in the world, with just over 27 percent of adults living with HIV (Avert, 2018). The majority of the population is poor. Women and child headed households are particularly affected (IFAD, 2010). Forestry, mixed farming, and irrigated sugar are practiced. However, most land is under subsistence farming on Swazi Nation Land, administered through the traditional chieftaincy system. Maize is the main staple crop and industrial activities are restricted to urban areas.

FIGURE 1.1 Ecological Zones of Swaziland.

Source: K. Middleton 2016.

Challenges in the Social-Ecological Systems

The Swaziland Water and Agricultural Enterprise (SWADE) was established in 1999 to develop smallholder agriculture. The following discussion illustrates selected socialecological challenges faced by SWADE.

■ SWADE’s development initiative is based on harvesting and providing water for irrigation. This led to the construction of the Maguga and Lubovane dams and a network of canals to supply irrigation water to 6,000 ha along the Komati River and 6,500 ha of cane in phase I and 5,750 in phase II of the Lower Usuthu valley. Thus, the search for suitable dam sites across the country, and establishment of similar structures, is key to the future expansion of SWADE’s activities.

■ Swaziland’s main rivers are shared water courses with South Africa and Mozambique. For example, Swaziland can only abstract 60 percent of the water in the Maguga dam (about 87 million cubic meters at full capacity) (Figure 1.2). Even in drought years, Swaziland must return 40 percent of the water into South Africa and onto Mozambique. Water abstraction is regulated by the Water Rights Act of 2003, an issue often not appreciated by local subsistence farmers. Joint Water Commissions have been established with the neighboring countries to manage international waters.

■ The irrigation expansion under smallholder development includes about 20,000 ha of irrigated cane. This is an addition to over 40,000 ha already under cane within the country owned by corporations and several commercial cane farmers (Figures 1.3 and 1.4). Sugar is also extensively grown in South Africa, while Mozambique is expanding its area under cane. There are economic risks associated with being dependent on a single crop as well as environmental problems arising from mono cropping, salinization, siltation, and eutrophication.

■ The resettlement of people affected by the irrigation project was done in line with the requirements of the Swaziland Environment Act 1992. Upstream, resettlement involved moving farmers away from the area to be flooded by the dam. Downstream, the main objective was to consolidate small individual parcels of land, less than 2 ha each, into commercially viable units of at least 50 ha in size. Land use practices changed from a mixed subsistence dry land cropping to a single crop susceptible to global price fluctuations.

■ Swaziland is prone to drought cycles . The 2015– 2016 season was one of the driest since 1992. The impact was greatest among communities relying on rain fed agriculture. Livestock were dying and communities struggled to obtain portable water. The cause of the drought was attributed to the el- Ni ñ o effect. SWADE responded to this challenge by introducing Climate Smarts Agriculture aimed at reducing poverty and food insecurity by applying drought resilient methods.

FIGURE 1.2 Maguga Dam estimated at 15 percent full in September 2016 (before the start of the rainy season) due to drought. Waterline when dam is full clearly visible.

Source: Photo by Rangarirai Taruvinga 2016.

Cane cutter harvesting cane. Runaway fires may force early harvesting.

Source: Photo by Rangarirai Taruvinga 2016.

FIGURE 1.3

■ Extension services. Parts of SWADE’s successes were due to different task teams assembled to support farmers. These included the social team, the agriculture team, the environment team, the training/extension team, and several ad hoc teams created as needed. These brought the necessary expertise and technology to the farmers.

■ The farmers were organized initially into farmer associations with collective responsibilities over their consolidated land investments; these subsequently were turned into limited liability companies with farmers as shareholders, who must appoint a board which in turn appoints a CEO to run their business. This arrangement created new challenges for the subsistence farmers’ understanding of how agricultural corporations are managed and operated. Over 100 such farming corporations were later found wanting in corporate governance.

■ SWADE has spent considerable funds to commercialize subsistence farming with an expectation of reducing poverty. However, a real challenge exists because of a highly dependent population and limited returns on investment per family. For example, the Mafucula community, which become part of SWADE initiative in 2004, has 250 members and is growing, and 286 ha of cane (SWADE, 2010). Annual dividend yields average only $200 per member. The expected increase in income that was assumed to lift rural communities out of poverty has not occurred (Taruvinga, 2011).

FIGURE 1.4 Cane haulage providing alternative employment to the cane farmers.

Source: Photo by Rangarirai Taruvinga 2016.

CONCLUSION

The discussion above illustrates the social-ecological issues faced by a rural development agency. Environmental complexity is a function of each subsystem and its effect on other subsystems. Complexity also arises from the temporal nature of events within the system. Things change over time, often reaching tipping points and becoming irreversible. It is not clear, for example, what the long-term effects of mono cropping on the environment are. Will salinity reach a point where cane growing will be abandoned? Economic activities today will affect societies tomorrow and long-term, and the ecological environment, contributing to climate change and combined with other generational activities, maybe having implications spanning geological time. Thus, for example, the effects of sugar farmers across the world and the many generations of agricultural practice may lead to the resulting changes being permanent.

Finally, we need to be aware of the analytical tools we can apply to better understand the complexity of the environment. Each subsystem requires further research and established tools such as social impact analysis, environmental impact assessment processes, geographic information system, value chains, climate change, and adaptability processes and carbon dating to help us understand the social-ecological complexity.

REFERENCES

Avert, 2018, HIV and AIDs in Swaziland. http://www.avert.org/professionsls/hiv-around-theworld/sub-saharan-africa/swaziland, last updated on May 21, 2018.

International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), 2010, “Rural poverty in the Kingdom of Swaziland.” http://www.ruralpovertyportal.org/country/home/tags/swaziland.

Swaziland Water and Agricultural Enterprise (SWADE), 2010, Welcome to SWADE. Swaziland Water and Agricultural Development Enterprise. http://www.swade.co.sz/index.html.

Taruvinga, M., 2011, “Commercialising subsistence farmers: A benefit or detriment to the poor?” Research report submitted to the Faculty of Humanities, Department of Sociology, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts Development Studies. The Government of Swaziland, 1992, Swaziland Environmental Act, Mbabane, Swaziland. The Government of Swaziland, 2003, Swaziland Water Act 2003, Mbabane, Swaziland. World Health Organization, 2000.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Rangarirai P. Taruvinga is the Director and CEO of Mananga Centre, a management development institute in Swaziland. He holds a doctorate in geography from University of Waterloo, Canada, and also studied at Sheffield University in the United Kingdom and Fourah Bay College in Sierra Leone. He has extensive experience in East and Southern Africa and lectures in development, environmental management, and business to managers and executives. His interests include land use planning, land reform, small holder agricultural development, and related human resources development.

1.3 THE ANTHROPOCENE

It is generally agreed that the Earth is 4.54 billion years old. The International Union of Geological Sciences has developed a geological time scale to identify significantly different time periods in the history of the Earth relative to stratigraphy or rock strata. The time scale

involves different categories termed eons, eras, periods, and epochs. Today, based on the geological time scale, we are in the Holocene epoch, which started 11,700 years ago and is one of two epochs (the other being the Pleistocene) within the Quaternary period which began 2.588 million years ago, which in turn is part of the Cenozoic era which began 65.5 million years ago (Table 1.1). The Quaternary period is also associated with the appearance of humans, as well as mammoths and mastodons.

In 2000, Crutzen and Stoermer suggested that it would be appropriate to identify a new epoch, and they proposed it be termed the Anthropocene. Their rationale was that humankind’s activities and impact had become a major geological and morphological force, and it was time to recognize that reality. Crutzen and Stoermer (2000: 17) argued that the growth of people and per capita exploitation of the Earth’s resources had grown at a geometric rate since the mid-1880s. To illustrate this reality, they noted that over the most recent three centuries the human population on the Earth had grown by a factor of 10, to reach 6 billion people. They also argued that during this time period humankind had been exhausting reserves of fossil fuels, had exponentially increased SO₂ emissions, was using more than half of freshwater on the Earth, and had increased the extinction of other living species in tropical rainforests by a factor of 10 thousand. Given this reality, they concluded that

Considering these and many other major and still growing impacts of human activities on earth and the atmosphere, and at all, including global scales, it seems to us more than appropriate to emphasize the central role of mankind in geology and ecology by proposing to use the term “anthropocene” for the current geological epoch. The impacts of current human activities will continue over long periods.

In brief, the core of their argument was that use of the term Anthropocene would be appropriate because in their view the Earth was evolving out of conditions that defined the Holocene epoch, and human activity was the main driving factor behind the changes. That is, humankind by itself had become a geological force (Steffen, Grinevald, Crutzen, and McNeill, 2011).

They appreciated the challenge in determining a starting point for a new epoch labeled as the Anthropocene, since the criteria would not be based on the traditional rock strata used in the

TABLE 1.1 Geological Time Scale

Era

Cenozoic

Period

Epoch

Quaternary Holocene

65.5 million years ago to today 2.588 million years ago to today

Neogene

Paleogene

Mesozoic

250.0 to 65.5 million years ago

Cretacious

Jurassic

Triassic

11,700 years ago to today

Pleistocene

2.588 million years ago to 11,700

geological time scale. Notwithstanding that difficulty, they proposed a start date in the second half of the eighteenth century, stating that evidence demonstrated this to be the time period in which glacial ice cores showed the start of significant growth of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, as well as what they termed notable changes appearing in biotic assembles in many lakes. They thus concluded that “mankind will remain a major geological force for many millenia, maybe millions of years to come. To develop a worldwide accepted strategy leading to sustainability of ecosystems against human induced stresses will be one of the great future tasks of mankind” (Crutzen and Stoermer, 2000: 18). They emphasized that resource and environmental managers would have to give attention to linked social and ecological systems, and understand that such issues were what have also been termed “wicked problems” characterized by ambiguity (both concepts treated in later sections).

Considerable debate and discussion emerged following the proposal by Crutzen and Stoermer. The International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) has a Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (2015), which noted the Anthropocene was not a formally recognized unit within the existing geological time scale. Given that challenge—but also the considerable support for the concept of naming a new epoch to be called the Anthropocene—the Commission noted that a working group on the Anthropocene had been established by the ICS with a mandate to report and provide a recommendation during 2016. The working group had been asked to consider whether it would be appropriate to add the Anthropocene as a new epoch, at the same hierarchical level as the Pleistocene and Holocene epochs (Table 1.1). The implication would be that the Holocene epoch had ended, and would be followed by the Anthropocene.

The 35-member working group met in Oslo during April 2016, and voted 30 to three, with two abstentions, in favor of formally declaring an Anthropocene epoch. It also suggested that the new epoch should be designated to have begun in about 1950. The working group subsequently presented its recommendation to the International Geological Congress in Cape Town, South Africa, in late August 2016. They supported their recommendation by noting that since the mid-twentieth century there has been a remarkable acceleration of carbon dioxide emissions, sea-level rise, mass extinction of species, and deforestation and development (Carrington, 2016).

The next major task will be to identify one or more “signals” that characterize the new epoch and are also found globally, and will be measurable in the geological record of the future. One of the best known examples of such a signal which defined the end of the Cretaceous period was the presence of metal iridium in sediments throughout the world caused by a meteorite that hit the Earth and triggered the end of the dinosaur age (Carrington, 2016). Thus, the working group will focus on identifying the best candidates for such signals. One view is that that presence of radioactive elements from nuclear bomb tests that were scattered into the atmosphere and then returned to settle on Earth is such a credible signal. However, other candidate signals need consideration, such as unburned carbon spheres released by power stations, as well as significant deposits of nitrogen and phosphate, from fertilizers, into soils. Thus, it is anticipated that the 35-member working group will spend two to three years to analyze and recommend the strongest signals. The working group also will have to determine a location which reflects the beginning of the Anthropocene. Once such data and recommendations have been determined, they will be submitted to the ICS. Such work could take up to three years.

Whatever the outcome from the working group’s analysis, its considering the possibility of the Anthropocene becoming a designated epoch reinforces the message at the outset of this chapter—that resource and environmental managers need to give attention to interlocked social and natural matters as they determine what decisions to take.

1.4 WICKED PROBLEMS

The wicked problem concept was proposed by Rittel and Webber (1973). Their key point was that many planning problems are challenging because numerous stakeholders with diverse values, attitudes, and preferences make it difficult to identify solutions that will be broadly supported. In their words, planning problems often “are ill-defined; and they rely upon elusive political judgement for resolution. (Not ‘solution.’ Social problems are never solved. At best they are only re-solved—over and over again).” They explained that they chose the term “wicked problem” not because its characteristics are ethically deplorable but because they reflect attributes such as malignancy, viciousness, trickiness, and aggressiveness. They also identified ten distinguishing properties of wicked problems, highlighted in Table 1.2.

As Weber and Shademian (2008: 336–337) observed, wicked problems have all the characteristics noted above by Turnpenny et al. (2009) in Box 1.1, and also by Ritter and Webber (1973), in Table 1.2. In particular, they emphasized that wicked problems are not structured. In other words, their causes and effects are problematic both to define and model, contributing to significant complexity and uncertainty which in turn usually creates considerable conflict due to lack of agreement on the nature of the problem or possible solutions.

TABLE 1.2 Properties of Wicked Problems

1. There is no definitive formulation of a wicked problem because information needed to understand the problem is a function of options considered to solve it.

2. Wicked problems have no stopping rule or ultimate solution, and effort allocated to them is influenced by available time, resources, and determination.

3. Solutions to wicked problems are not true or false, but are good or bad, a judgment influenced by the values of those assessing them.

4. There is neither an immediate nor ultimate test of a solution to a wicked problem because implementation of a solution triggers consequences over a long period of time, with some consequences unexpected and so undesirable that it would have been better to have done nothing.

5. Every solution to a wicked problem is a one-shot operation, and because results often cannot be undone, opportunity frequently does not exist to learn by trial and error (e.g., large public works are usually irreversible).

6. Wicked problems do not have an obvious set of definitive solutions.

7. Every wicked problem is distinctive, and often even unique. Thus, no categories of wicked problems can be created in the sense that principles or solutions will align with every specific problem.

8. Every wicked problem will be a symptom of another problem at a lower and/or higher spatial scale.

9. The presence of one or more discrepancies associated with a wicked problem can be explained in numerous ways. This reinforces point (7) that each wicked problem is at least distinctive and often unique.

10. A planner has no right to be wrong or incorrect, given that the environment, economy, and people will be affected by decisions taken, and impacts of decisions taken can be significant and long-term.

Source: Rittel and Webber, 1973: 161–167.

BOX 1.1

A PERSPECTIVE ON WICKED PROBLEMS

The term “wicked” is often used to describe issues with particularly incomplete, contradictory, and changing requirements. Complex interdependencies, difficulties in defining the problems themselves, and difficulty in identifying—and often in reaching consensus on—solutions all contribute to wickedness.

Source: Turnpenny, Lorenzoni, and Jones, 2009: 347.

They also observed that wicked problems contain “multiple, overlapping, interconnected subsets of problems that cut across multiple problem domains and levels of governments” (336). The implication is that a wicked problem is connected to other problems which can generate both conflict and uncertainty. And, finally, they comment that wicked problems are often “relentless,” implying that they will seldom be solved definitively for everyone affected, notwithstanding best intentions and efforts. Using the analogy of a pebble dropped into water, they comment that ripples from a wicked problem will spread rapidly and affect other issues. They illustrate this observation by noting that habitat restoration initiatives for endangered species will have ripple effects related to hunting and fishing practices, balance and mix of species and plants, and farming activity.

The above discussion emphasizes that we can expect to encounter wicked problems, and will find them challenging to handle. However, we should not become pessimistic or negative. In that regard, it is helpful to consider the view of Caton Campbell (2003: 361), who used a similar term when she stated that many resource and environmental problems are intractable. While she notes that some interpret intractability to characterize issues which defy resolution, her view, consistent with that of Gray (1997), is that the concept of intractability indicates a problem resistant to resolution rather than one which is unresolvable. To help us identify issues with such characteristics, she identifies a number to be aware of, including that they (1) are founded on fundamental or deep-rooted moral conflict; (2) involve basic value differences between and among stakeholders; (3) reflect fundamental conflict regarding world views, values, and principles; (4) relate to conflict that has persisted; (5) reflect significant imbalance of power among stakeholders; (6) are capable of escalating into violence; (7) reflect high levels of hostility and rigidity of viewpoints; (8) are based on strongly held beliefs or positions; (9) reflect complex and interconnected issues; (10) involve distributional questions involving high stakes; (11) often involve one-upmanship by those engaged in the issue; and (12) can pose threats to identities of individuals or groups (Caton Campbell, 2003: 363). These 12 characteristics do not lead to a recipe or formula to deal with a wicked or intractable problem, but they can help us to appreciate what is involved, and therefore we will need to be patient, disciplined, determined, and persevering to figure out how to deal with it.

1.4.1 Climate Change as a Wicked Problem

Climate change is a good example of a wicked problem. As Head (2014: 663) has commented, the related scientific and public policy issues regarding climate change began to be articulated in the late 1980s, but today the controversy continues. In his view, while

countries in Western Europe have generally accepted the significance and implications of climate change, in other world regions, especially in the United States, Canada, and Australia, the approach to climate change often has been characterized by “avoidance and nondecision.” He attributes the reasons for such a response in those three countries to “ideological politics, linked to a strident defense of entrenched economic interests, and the deliberate creation of uncertainty about causes and consequences” (Head, 2014: 663). In his view, the basic wicked nature of climate change and related policies was consciously “inflamed for partisan reasons to undermine the possibility of consensus formation.”

Head (2014: 665) stated that the 10 characteristics of wicked problems in Table 1.2 were never intended to suggest no action could be taken or be effective. However, he argued that the view of Rittel and Webber was that the nature of wicked problems demands government decision-makers to embrace uncertainty, along with divergent stakeholders’ viewpoints. The implications are that an adaptive management approach (discussed more in chapters 4 and 5) is required. In particular, in such an approach it is critically important to engage stakeholders in order to identify key information, determine options, and identify solutions, as well as to appreciate that any solutions should be viewed as provisional and undoubtedly will need modification over time (chapter 6). Head observed that such an approach is usually not embraced enthusiastically by politicians, who he argues are normally sensitive to opinion polls, nor by senior managers in the public sector, who are expected to develop clear and specific objectives, identify explicit milestones or benchmarks related to each objective, and achieve outcomes both on time and on budget.

Thus, Head (2014: 666) identified various reasons for why climate change strategies and responses should be approached as dealing with a wicked problem. First, planners, managers, and decision-makers are not dealing with climate change as an isolated problem because it overlaps and interacts with other issues related to energy, water, health, and food production. Given such a characteristic, Lazarus (2009) termed climate change a “super wicked problem” because of the diverse legal and regulatory difficulties associated with it. Second, both short- and long-term variations occur related to impacts, costs, and benefits associated with different possible solutions, and such variations may shift over time. Third, impacts simultaneously occur at local, regional, national, and international spatial scales, adding complexity and uncertainty. Fourth, the scientific knowledge base, the nature of climate change, and the role of humans in causing such change have been continuously challenged and debated, often by stakeholders with specific interests to protect and promote. For some participants, it is to their advantage to cause confusion, doubt, and uncertainty about knowledge and choices. And, fifth, at a national scale some want only to protect the economy of their country, even if actions taken in and by their country cause significant negative impacts for other countries. Thus, climate change is a multidimensional issue, with connections to many other significant resource and environmental issues. On that basis, it readily reflects the attributes of wicked problems, and thus reminds us that solutions for it will be challenging to determine.

1.5 AMBIGUITY

The idea of a wicked problem can be understood at a deeper level by considering the concept of “ambiguity,” the focus here. As Brugnach et al. (2011: 78) have remarked, “ambiguity is a distinct type of uncertainty that results from the simultaneous presence of multiple valid, and sometimes conflicting, ways of framing a problem.” In their view, ambiguity can hinder our understanding of a problem or issue, as well as complicate finding a solution. Ambiguity often arises due to resource and environmental managers reaching

out to engage with stakeholders. Specifically, such engagement often makes it obvious that more than one way exists to view or characterize an issue or problem. Such differences can become exacerbated when a range of stakeholders comes together in a public engagement process. Brugnach et al. (2011: 78) concluded that such a situation can result “in ambiguity: it is no longer clear what exactly the problem is.”

What can be done to address ambiguity? Brugnach and Ingram (2012: 66–67) suggest that two approaches offer promise for creating capacity to reflect different perspectives. They term one as dialogical learning, which uses both dialogue and learning in order to recognize and respect different perspectives or knowledge “frames.” The hope and expectation is that open dialogue between and among stakeholders with different views will lead to mutual understanding that will create a new, shared, and connected frame related to an issue or problem. A key assumption in this approach is that different stakeholders are open to listening to one another, to having their perspectives or frames questioned and challenged, and to consider modifying their views and positions. In other words, willingness exists to participate in open dialogue.

A second approach, labeled negotiation (discussed in more detail in chapter 7), recognizes the presence of different frames by seeking agreement via negotiation. The intent is not to develop a new and shared frame, but rather to reach a fair arrangement through discussions among stakeholders. Individual stakeholders normally maintain their frames or positions, and this approach is used when the various frames are so different that the probability of effective dialogical learning is judged to be low.

Neither of the above two approaches guarantees that their application will resolve aspects of ambiguity, because, as observed by Brugnach and Ingram (2012: 67), “conflicts among the parties, polarization of views, oppositional modes of actions can preclude their applicability in real life situations.” As a result, judgment is always required to determine which of these two or other approaches might be the best fit in a particular situation. When conflict is a core element contributing to ambiguity, other conflict resolution methods, discussed in chapter 7, may be more applicable.

1.6 CASE STUDY: MINERALS IN THE PHILIPPINES

Verbrugge (2014: 449) suggests that decentralization of governance arrangements for natural resource management is being used across the globe, in order that decisions are taken with appreciation for their implications at the local level. However, while the benefits of decentralized governance are generally real, awareness also exists that it can lead to institutional uncertainty that may trigger conflicts among stakeholders keen to obtain access to mineral resources. These issues are discussed further in chapter 4, related to governance.

Specifically, Verbrugge (2014: 449) suggests that, as emphasized in Box 1.2, when numerous and uncoordinated initiatives are taken to facilitate decentralized governance, ambiguous institutional arrangements can be created, particularly because of “pervasive uncertainty regarding rule interpretation and enforcement.” In his view, the associated institutional ambiguity can create conditions which facilitate challenges for and renegotiation of governance arrangements, leading to a redistribution of benefits during extraction of mineral resources. Such renegotiation, he suggests, is ultimately a political process, and involves a mix of conflicts among continuously evolving stakeholders such as government officials at various spatial scales, large mining companies, small mining operations, tribal groups, and armed groups. In such a diverse mix of players and conflicts, he suggests that local politicians are a common element.