Representation in Cognitive Science

Nicholas Shea

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© Nicholas Shea 2018

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2018

Impression: 1

Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization.

This is an open access publication, available online and distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial – No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of this licence should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018939590

ISBN 978–0–19–881288–3

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

To Ellie

Huffing and puffing with correlation and function might give us a good account of subdoxastic aboutness . . . [but it is unlikely to work for the content of doxastic states.] *

Martin Davies (pers. comm.), developed in Davies (2005)

* Not that the antecedent is easy. And even for the subpersonal case we may have to puff on a few more ingredients. But I too am optimistic that we can get a good account. This book aims to show how.

Preface

The book is in three parts: introduction, exposition, and defence. Part I is introductory and light on argument. Chapter 1 is about others’ views. Chapter 2 is the framework for my own view. I don’t rehearse well-known arguments but simply gesture at the literature. The aim is to demarcate the problem and motivate my own approach. Part II changes gear, into more standard philosophical mode. It aims to state my positive view precisely and to test it against a series of case studies from cognitive science. Part III engages more carefully with the existing literature, showing that the account developed in Part II can deal with important arguments made by previous researchers, and arguing that the framework put forward in Part I has been vindicated.

There is a paragraph-by-paragraph summary at the end of the book. Readers who want to go straight to a particular issue may find this a useful guide. It replaces the chapter summaries often found at the end of each chapter of a monograph. The bibliography lists the pages where I discuss each reference, so acts as a fine-grained index to particular issues. There is also the usual keyword index at the end.

2.4

2.5

3.6

4.3

4.6

4.7

4.8

4.9

5.

5.1

5.2

5.3

5.4

5.6

5.7

6.3

6.4

6.5

7.

7.1

7.2

7.3

7.4

7.5

7.6

8.

8.3

8.4

8.5

PART I

1.1

1.2

1.4 Teleosemantics

1.5

1.1 A Foundational Question

The mind holds many mysteries. Thinking used to be one of them. Staring idly out of the window, a chain of thought runs through my mind. Concentrating hard to solve a problem, I reason my way through a series of ideas until I find an answer (if I’m lucky). Having thoughts running through our minds is one of the most obvious aspects of the lived human experience. It seems central to the way we behave, especially in the cases we care most about. But what are thoughts and what is this process we call thinking? That was once as mysterious as the movement of the heavens or the nature of life itself. New technology can fundamentally change our understanding of what is possible and what mysterious. For Descartes, mechanical automata were a revelation. These fairground curiosities moved in ways that looked animate, uncannily like the movements of animals and even people. A capacity that had previously been linked inextricably to a fundamental life force, or to the soul, could now be seen as purely mechanical. Descartes famously argued that this could only go so far. Mechanism would not explain consciousness, nor the capacity for free will. Nor, he thought, could mechanism explain linguistic competence. It was inconceivable that a machine could produce different arrangements of words so as to give an appropriately grammatical answer to questions asked of it.1 Consciousness and free will remain baffling. But another machine has made what was inconceivable to Descartes an everyday reality to us. Computers produce appropriately arranged strings of words—Google even annoyingly finishes half-typed sentences—in ways that at least respect the meaning of the words they churn out. Until quite recently a ‘computer’ was a person who did calculations. Now we know that calculations can be done mechanically. Babbage,

1 Descartes (1637/1988, p. 44: AT VI 56: CSM I I40), quoted by Stoljar (2001, pp. 405–6).

Lovelace, and others in the nineteenth century saw the possibility of general-purpose mechanical computation, but it wasn’t until the valve-based, then transistor-based computers of the twentieth century that it became apparent just how powerful this idea was.2

This remarkable insight can also answer our question about thinking: the answer is that thinking is the processing of mental representations. We’re familiar with words and symbols as representations, from marks made on a wet clay tablet to texts appearing on the latest electronic tablet: they are items with meaning.3 A written sentence is a representation that takes the form of ink marks on paper: ‘roses are red’. It also has meaning—it is about flowers and their colour. Mental representations are similar: I believe that today is Tuesday, see that there is an apple in the bowl, hope that the sun will come out, and think about an exciting mountain climb. These thoughts are all mental representations. The core is the same as with words and symbols. Mental representations are physical things with meaning. A train of thought is a series of mental representations. That is the so-called ‘representational theory of mind’.

I say the representational theory of mind is ‘an’ answer to our question about thinking, not ‘the’ answer, because not everyone agrees it is a good idea to appeal to mental representations. Granted, doing physical manipulations on things that have meaning is a great idea. We count on our fingers to add up. We manipulate symbols on the page to arrive at a mathematical proof. The physical stuff being manipulated can take many forms. Babbage’s difference engine uses gears and cogs to do long multiplication (see Figure 1.1). And now our amazingly powerful computers can do this kind of thing at inhuman speed on an astonishing scale. They manipulate voltage levels not fingers and can do a lot more than work out how many eggs will be left after breakfast. But they too work by performing physical manipulations on representations. The only trouble with carrying this over to the case of thinking is that we’re not really sure how mental representations get their meaning.

For myself, I do think that the idea of mental representation is the answer to the mystery of thinking. There is very good reason to believe that thinking is the processing of meaningful physical entities, mental representations. That insight is one of the most important discoveries of the twentieth century—it may turn out to be the most important. But I have to admit that the question of meaning is a little problem in the foundations. We’ve done well on the ‘processing’ bit but we’re still a bit iffy about the ‘meaningful’ bit. We know what processing of physical particulars is, and how processing can respect the meaning of symbols. For example, we can make a machine whose manipulations obey logical rules and so preserve truth. But we don’t yet have a clear idea of how representations could get meanings, when the meaning does not derive from the understanding of an external interpreter.

2 Developments in logic, notably by Frege, were of course an important intermediate step, on which Turing, von Neumann, and others built in designing computing machines.

3 We’ll have to stretch the point for some of my son’s texts.

Figure 1.1 Babbage’s difference engine uses cogs and gears to perform physical manipulations on representations of numbers. It is used to multiply large numbers together. The components are representations of numbers and the physical manipulations make sense in the light of those contents—they multiply the numbers (using the method of differences).

So, the question remains: how do mental states4 manage to be about things in the external world? That mental representations are about things in the world, although utterly commonplace, is deeply puzzling. How do they get their aboutness? The physical and biological sciences offer no model of how naturalistically respectable properties could be like that. This is an undoubted lacuna in our understanding, a void hidden away in the foundations of the cognitive sciences. We behave in ways that are suited to our environment. We do so by representing the world and processing those representations in rational ways—at least, there is strong evidence that we do in very many cases. Mental representations represent objects and properties in the world: the

4 I use ‘mental’ broadly to cover all aspects of an agent’s psychology, including unconscious and/or low-level information processing; and ‘state’ loosely, so as to include dynamic states, i.e. events and processes. ‘Mental state’ is a convenient shorthand for entities of all kinds that are psychological and bear content.

shape of a fruit, the movement of an animal, the expression on a face. I work out how much pasta to cook by thinking about how many people there will be for dinner and how much each they will eat. ‘Content’ is a useful shorthand for the objects, properties and conditions that a representation refers to or is about. So, the content of one of my thoughts about dinner is: each person needs 150g of pasta.

What then is the link between a mental representation and its content? The content of a representation must depend somehow on the way it is produced in response to input, the way it interacts with other representations, and the behaviour that results. How do those processes link a mental representation with the external objects and properties it refers to? How does the thought in my head connect up with quantities of pasta? In short: what determines the content of a mental representation? That is the ‘content question’. Surprisingly, there is no agreed answer.

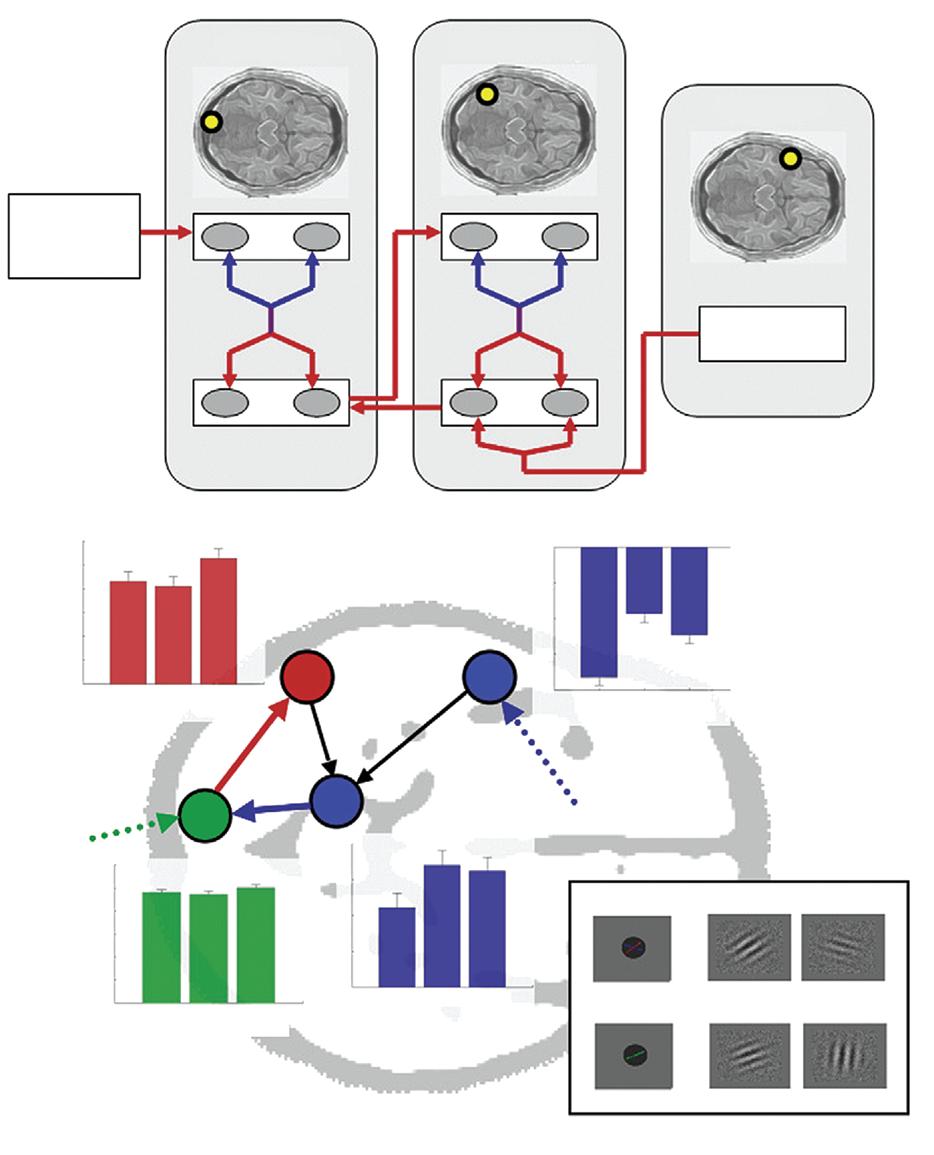

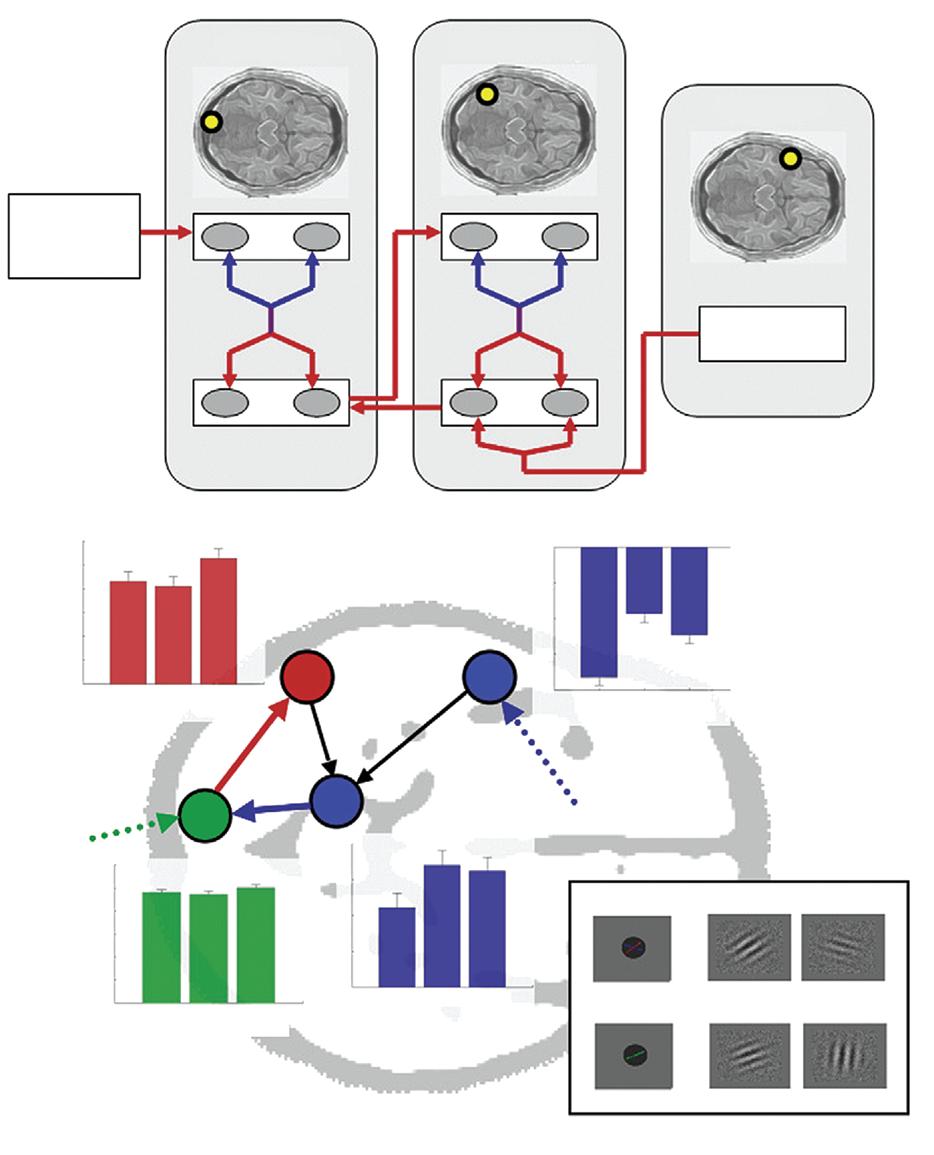

This little foundational worry hasn’t stopped the cognitive sciences getting on and using the idea of mental representation to great effect. Representational explanation is the central resource of scientific psychology. Many kinds of behaviour have been convincingly explained in terms of the internal algorithms or heuristics by which they are generated. Ever since the ‘cognitive revolution’ gave the behavioural sciences the idea of mental representation, one phenomenon after another has succumbed to representational explanation, from the trajectories of the limbs when reaching to pick up an object, to parsing the grammar of a sentence. The recent successes of cognitive neuroscience depend on the same insight, while also telling us how representations are realized in the brain, a kind of understanding until recently thought to be fanciful. Figure 1.2 shows a typical example. The details of this experiment need not detain us for now (detailed case studies come in Part II). Just focus on the explanatory scheme. There is a set of interconnected brain areas, plus a computation being performed by those brain areas (sketched in the lower half of panel (a)). Together that tells us how participants in the experiment manage to perform their task (inset). So, although we lack a theory of it, there is little reason to doubt the existence of representational content. We’re in the position of the academic in the cartoon musing, ‘Well it works in practice, Bob, but I’m not sure it’s really gonna work in theory.’

The lack of an answer to the content question does arouse suspicion that mental representation is a dubious concept. Some want to eliminate the notion of representational content from our theorizing entirely, perhaps replacing it with a purely neural account of behavioural mechanisms. If that were right, it would radically revise our conception of ourselves as reason-guided agents since reasons are mental contents. That conception runs deep in the humanities and social sciences, not to mention ordinary life. But even neuroscientists should want to hold onto the idea of representation, because their explanations would be seriously impoverished without it. Even when the causes of behaviour can be picked out in neural terms, our understanding of why that pattern of neural activity produces this kind of behaviour depends crucially on neural activity being about things in the organism’s environment. Figure 1.2 doesn’t just show neural areas, but also how the activity of those areas should be understood as

Figure 1.2 A figure that illustrates the explanatory scheme typical of cognitive neuroscience (from Rushworth et al. 2009). There is a computation (sketched in the lower half of panel (a)), implemented in some interacting brain areas, so as to perform a behavioural task (inset). The details are not important for present purposes.

representing things about the stimuli presented to the people doing a task. The content of a neural representation makes an explanatory connection with distal features of the agent’s environment, features that the agent reacts to and then acts on.

One aspect of the problem is consciousness. I want to set that aside. Consciousness raises a host of additional difficulties. Furthermore, there are cases of thinking and

reasoning, or something very like it, that go on in the absence of consciousness. Just to walk along the street, your eyes are taking in information and your mind is tracking the direction of the path and the movement of people around you. Information is being processed to work out how to adjust your gait instant by instant, so that you stay on your feet and avoid the inconvenience of colliding with the person in front engrossed in their smartphone. I say those processes going on in you are a kind of reasoning, or are like familiar thought processes, because they too proceed through a series of states, states about the world, in working out how to act. They involve processing representations in ways that respect their contents. Getting to grips with the content of nonconscious representations is enough of a challenge in its own right.5

The content question is widely recognized as one of the deepest and most significant problems in the philosophy of mind, a central question about the mind’s place in nature. It is not just of interest to philosophers, however. Its resolution is also important for the cognitive sciences. Many disputes in psychology concern which properties are being represented in a particular case. Does the mirror neuron subsystem represent other agents’ goals or merely action patterns (Gallese et al. 1996)? Does the brain code for scalar quantities or probability distributions (Pouget et al. 2003)? Do infants represent other agents’ belief states or are they just keeping track of behaviour (Apperly and Butterfill 2009)? Often such disputes go beyond disagreements about what causal sensitivities and behavioural dispositions the organism has. Theorists disagree about what is being represented in the light of those facts. What researchers lack is a soundly based theory of content which tells us what is being represented, given established facts about what an organism or other system responds to and how it behaves.

This chapter offers a breezy introduction to the content question for non-experts. I gesture at existing literature to help demarcate the problem, but proper arguments will come later (Parts II and III). So that I can move quickly to presenting the positive account (Chapter 2 onwards), this chapter is more presupposition than demonstration. It should bring the problem of mental content into view for those unfamiliar with it, but it only offers my own particular take on the problem.

1.2 Homing In on the Problem

The problem of mental content in its modern incarnation goes back to Franz Brentano in the nineteenth century. Brentano identified aboutness or ‘intentionality’6 as being a peculiar feature of thoughts (Brentano 1874/1995). Thoughts can be about objects and properties that are not present to the thinker (the apple in my rucksack), are distant in time and space (a mountain in Tibet), are hypothetical or may only lie far in the future (the explosion of the sun), or are entirely imaginary (Harry Potter). How can mental

5 Roughly, I’m setting aside beliefs and desires (doxastic states) and conscious states—see §2.1. I use ‘subpersonal’ as a label for mental representations that don’t have these complicating features.

6 This is a technical term—it’s not about intentions.

states reach out and be about such things? Indeed, how do beliefs and perceptual states manage to be about an object that is right in front of the thinker (the pen on my desk), when the object is out there, and the representations are inside the thinker?

We could ask the same question about the intentionality of words and natural language sentences: how do they get their meaning? An obvious answer is: from the thoughts of the language users.7 The meaning of a word is plausibly dependent on what people usually take it to mean: ‘cat’ is about cats because the word makes people think about cats. That kind of story cannot then be told about mental representations, on pain of regress. In order to start somewhere we start with the idea that at least some mental representations have underived intentionality. If we can’t make sense of underived intentionality somewhere in the picture—of where meaning ultimately comes from—then the whole framework of explaining behaviour in terms of what people perceive and think is resting on questionable foundations. The most fruitful idea in the cognitive sciences, the idea of mental representation, which we thought we understood, would turn out to be deeply mysterious, as difficult as free will or as consciousness itself.

When asked about the content of a familiar mental representation like a concept, one common reaction is to talk about other mental states it is associated with. Why is my concept dog about dogs?8 Because it brings to mind images of dogs, the sound of dogs barking, the feel of their fur and their distinctive doggy smell. We’ll come back to these kinds of theories of content in the next section, but for now I want to point out that this answer also just pushes back the question: where do mental images get their contents? In virtue of what do they represent the visual features, sounds, tactile properties and odours that they do? Underived intentionality must enter the picture somewhere.

The task then is to give an account of how at least some mental representations have contents that do not derive from the contents of other representations. What we are after is an account of what determines the content of a mental representation, determination in the metaphysical sense (what makes it the case that a representation has the content it does?) not the epistemic sense (how can we tell what the content of mental representation is?). An object-level semantic theory gives the content of mental representations in a domain (e.g. tells us that cognitive maps refer to spatial locations). Many information-processing accounts of behaviour offer a semantic theory in this sense. They assign correctness conditions and satisfaction conditions to a series of mental representations and go on to say how those representations are involved in generating intelligent behaviour. Our question is a meta-level question

7 Another tenable view is that sentences have underived intentionality. For beliefs and desires, the claim that their content derives from the content of natural language sentences has to be taken seriously. But here I set aside the problem of belief/desire content (§2.1) to focus on simpler cases in cognitive science.

8 I use small caps to name concepts; and italics when giving the content of a representation (whether a subpropositional constituent, as here, or a full correctness condition or satisfaction condition). I also use italics when introducing a term by using (rather than mentioning) it.

about these theories: in virtue of what do those representations have those contents (if indeed they do)? For example, in virtue of what are cognitive maps about locations in the world? Our task then is to formulate a meta-semantic theory of mental representation.

It is popular to distinguish the question of what makes a state a representation from the question of what determines its content (Ramsey 2007). I don’t make that distinction. To understand representational content, we need an answer to both questions. Accordingly, the accounts I put forward say what makes it the case, both that some state is a representation, and that it is a representation with a certain content.

We advert to the content of representations in order to explain behaviour. To explain how you swerve to avoid an oncoming smartphone zombie, the psychologist points to mental processes that are tracking the trajectory of people around you. A theory of content can illuminate how representations play this kind of explanatory role. One central explanatory practice is to use correct representations to explain successful behaviour. That assumption is more obviously at work in its corollary: misrepresentation explains failure. Because she misperceived the ground, she stumbled. Because he thought it was not yet eight o’clock, he missed the train. Misrepresentation explains why behaviour fails to go smoothly or fails to meet an agent’s needs or goals. When things go badly for an agent, we can often pin the blame on an incorrect representation. We can also often explain the way they do behave; for instance, misrepresenting the time by fifteen minutes explains why he arrived on the platform nearly fifteen minutes after the train left.

Misrepresentation is one of the most puzzling aspects of representational content. A mental representation is an internal physical particular. It could be a complex pattern of neural activity. Cells firing in the hippocampus tell the rat where it is in space so it can work out how to get to some food at another location. If the cell firing misrepresents its current location, the rat will set off in the wrong direction and fail to get to the food. Whether a representation is correct or incorrect depends on factors outside the organism, which seem to make no difference to how the representation is processed within the organism (e.g. to how activity of some neurons causes activity of others). Yet its truth or falsity, correctness or incorrectness, is supposed to make a crucial explanatory difference. The capacity to misrepresent, then, is clearly a key part of what makes representational content a special kind of property, a target of philosophical interest. Any good theory of content must be able to account for misrepresentation.

A theory of content need not faithfully recapitulate the contents relied on in psychological or everyday explanations of behaviour. It may be revisionary in some respects, sometimes implying that what is actually represented is different than previously thought. Indeed, a theory of content can, as I suggested, help arbitrate disputes between different proposed content assignments.9 However, it should deliver reasonably determinate contents. A theory of content needs to be applicable in concrete cases.

9 E.g. whether infants are tracking others’ mental states or just their behaviour.

For example, reinforcement learning based on the dopamine subsystem explains the behaviour elicited in a wide range of psychological experiments. We can predict what people will choose if we know how they have been rewarded for past choices. Plugging in facts about what is going on in a concrete case, a theory of content should output correctness conditions and/or satisfaction conditions for the representations involved. The determinacy of those conditions needs to be commensurate with the way correct and incorrect representation explains successful and unsuccessful behaviour in the case in question. A theory of content would obviously be hopeless if it implied that every state in a system represents every object and property the system interacts with. Delivering appropriately determinate contents is an adequacy condition on theories of content.

The problem of determinacy has several more specific incarnations. One asks about causal chains leading up to a representation. When I see a dog and think about it, is my thought about the distal object or about the pattern of light on my retina? More pointedly, can a theory of content distinguish between these, so that it implies that some mental representations have distal contents, while others represent more proximal matters of fact? A second problem is that the objects we think about exemplify a whole host of properties at once: the dog is a member of the kind dog, is brown and furry, is a medium-sized pliable physical object, and so on. The qua problem asks which of these properties is represented. Finally, for any candidate contents, we can ask about their disjunction. A theory may not select between that is a dog and that is a brown, furry physical object but instead imply that a state represents that is a dog or that is a brown, furry physical object. Rather than misrepresenting an odd-looking fox as a dog, I would end up correctly representing it as a brown furry object. If every condition in which this representation happens to be produced were included, encompassing things like shaggy sheep seen from an odd angle in poor light, then the representation would never end up being false. Every condition would be found somewhere in the long disjunction. We would lose the capacity to misrepresent. For that reason, the adequacy condition that a theory of content should imply or explain the capacity for misrepresentation is sometimes called the ‘disjunction problem’. The qua problem, the disjunction problem, and the problem of proximal/distal contents are all different guises of the overall problem of determinacy.

Since we are puzzled about how there could be representational contents, an account of content should show how content arises out of something we find less mysterious. An account in terms of the phenomenal character of conscious experience, to take one example, would fail in this respect.10 Standardly, naturalistic approaches offer accounts of content that are non-semantic, non-mental, and non-normative. I am aiming for an account that is naturalistic in that sense. Of course, it may turn out that there

10 That is not in itself an argument against such theories—it could turn out that intentionality can only be properly accounted for in phenomenal terms—but it is a motivation to see if a non-phenomenal theory can work.

is no such account to be had. But in the absence of a compelling a priori argument that no naturalistic account of mental representation is possible, the tenability of the naturalistic approach can only properly be judged by the success or failure of the attempt. The project of naturalizing content must be judged by its fruits.

1.3 Existing Approaches

This section looks briefly at existing approaches to content determination. I won’t attempt to make a case against these approaches. Those arguments have already been widely canvassed. My aim is to introduce the main obstacles these theories have faced, since these are the issues we will have to grapple with when assessing the accounts of content I put forward in the rest of the book. Although the theories below were advanced to account for the content of beliefs, desires, and conscious states, the same issues arise when they are applied to neural representations and the other cases from cognitive science which form the focus of this book.

One obvious starting point is information in the weak sense of correlation.11 Correlational information arises whenever the states of items correlate, so that item X’s being in one state (smoke is coming from the windows) raises the probability that item Y is in another state (there is a fire in the house). A certain pattern of neural firing raises the probability that there is a vertical edge in the centre of the visual field. If the pattern of firing is a neural representation, then its content may depend on the fact that this pattern of activity makes it likely that there is a vertical edge in front of the person. Information theory has given us a rich understanding of the properties of information in this correlational sense (Cover and Thomas 2006). However, for reasons that have been widely discussed, representational content is clearly not the same thing as correlational information. The ‘information’ of information-processing psychology is a matter of correctness conditions or satisfaction conditions, something richer than the correlational information of information theory. Sophisticated treatments use the tools of information theory to construct a theory of content which respects this distinction (Usher 2001, Eliasmith 2013). However, the underlying liberality of correlational information continues to make life difficult. Any representation carries correlational information about very many conditions at once, so correlation does not on its own deliver determinate contents. Some correlations may be quite weak, and it is not at all plausible that the content of a representation is the thing it correlates with most strongly.12 A weak correlation that only slightly raises the

11 Shannon (1948) developed a formal treatment of correlational information—as a theory of communication, rather than meaning—which forms the foundation of (mathematical) information theory. Dretske (1981) applied information theory to the problem of mental content.

12 Usually the strongest correlational information carried by a neural representation concerns other neural representations, its proximal causes, and its effects. The same point is made in the existing literature about beliefs. My belief that there is milk in the fridge strongly raises the probability that I have been thinking about food, only rather less strongly that there actually is milk in the fridge.

chance that there is a predator nearby may be relied on for that information when the outcome is a matter of life or death. Representations often concern distal facts, like the presence of a certain foodstuff, even though they correlate more strongly with a proximate sensory signal. Furthermore, a disjunction of conditions is always more likely than conditions taken individually: for example, an object might be an eagle, but it is more likely that it is an eagle or a crow. So, content-as-probability-raising faces a particularly acute form of the disjunction problem. Correlational information may well be an ingredient in a theory of content (Chapter 4), but even the sophisticated tools of mathematical information theory are not enough, without other ingredients, to capture the core explanatory difference between correct representation and misrepresentation.

Another tactic looks to relations between representations to fix content. We saw the idea earlier that the concept dog gets its meaning from the inferences by which it is formed, such as from perceiving a brown furry object, and perhaps also from conclusions it generates, such as inferring that this thing might bite me (Block 1986). Patterns of inferences are plausibly what changes when a child acquires a new mathematical concept (Carey 2009). They are also the focus of recent Bayesian models of causal learning (Gopnik and Wellman 2012, Danks 2014). Moving beyond beliefs to neural representations, dispositions to make inferences—that is, to transition between representations—could fix content here too. If all inferences are relevant, holism threatens (Fodor and Lepore 1992): any change anywhere in the thinker’s total representational scheme would change the content of all of their representations. There have been attempts to identify, for various concepts, a privileged set of dispositions that are constitutive of content (e.g. Peacocke 1992). However, it has proven difficult to identify sets of inferences that can do the job: that are necessary for possessing the concept, plausibly shared by most users of the concept, and sufficiently detailed to be individuative—that is, to distinguish between different concepts. For these reasons, inferential role semantics has not had much success in naturalizing content, except perhaps for the logical constants. The same concerns carry over when we move from beliefs to other representations relied on in the cognitive sciences.13 Relations amongst representations may be important for another reason. They endow a system of representations with a structure, which may mirror a structure in the world. For example, spatial relations between symbols on a map mirror spatial relations between places on the ground; and that seems to be important to the way maps represent. In the same way, Paul Churchland has argued that the similarity structure on a set of mental representations of human faces determines that they pick out certain

13 Concepts (the constituents of beliefs) are usually thought to have neo-Fregean sense, as well as referential content (content that contributes to truth conditions). We may well have to appeal to inferential relations between concepts to account for differences in sense between co-referential concepts, and/or to vehicle properties (Millikan 2000, Sainsbury and Tye 2007, Recanati 2012). This book does not deal with concepts. I leave aside the issue of whether we need to appeal to neo-Fregean senses in addition to vehicle properties and referential contents.