Preface

The economic and cultural changes linked with modernization tend to bring declining emphasis on religion—and in high-income societies this process recently reached a tipping point at which it accelerates. This book tests these claims against empirical evidence from countries containing 90 percent of the world’s population, explaining why this is happening and exploring what will come next.

Secularization has accelerated. From 1981 to 2007, most countries became more religious—but from 2007 to 2020, the overwhelming majority became less religious. For centuries, all major religions encouraged norms that limit women to producing as many children as possible and discourage any sexual behavior not linked with reproduction. These norms were needed when facing high infant mortality and low life expectancy but require suppressing strong drives and are rapidly eroding. These norms are so strongly linked with religion that abandoning them undermines religiosity. Religion became pervasive because it was conducive to survival, encouraged sharing when there was no social security system, and is conducive to mental health and coping with insecure conditions. People need coherent belief systems, but religion is declining.

The Nordic countries have consistently been at the cutting edge of cultural change and can provide an idea of what lies ahead. They were initially shaped by Protestantism, but their 20th-century social democratic welfare systems added universal health coverage; high levels of state support for education, welfare spending, child care, and pensions; and an ethos of social solidarity. The Nordic countries are also characterized by rapidly declining religiosity. Does this portend corruption and nihilism? Apparently not. These countries lead the world on numerous indicators of a well-functioning society, including economic equality, gender equality, low homicide rates, subjective well-being, environmental protection, and democracy. They have become less religious, but their people have high levels of interpersonal trust, tolerance, honesty, social solidarity, and commitment to democratic norms. The decline of religiosity has far-reaching implications. This book explores what comes next.

These findings build on previous work with Pippa Norris, particularly Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide (Norris & Inglehart, 2004/2011). Despite Sacred and Secular’s relatively recent publication, major changes have occurred since it appeared, and these changes shed new light on how religion is evolving.

I express my gratitude to the people who made the present book possible by carrying out the World Values Survey (WVS) and the European Values Study (EVS) in over 100 countries, from 1981 to 2020. My heartfelt thanks go to the following WVS and EVS principal investigators for creating and sharing this rich and complex dataset: Salvatore Abbruzzese, Abdel-Hamid AbdelLatif, Anthony M. Abela, Marchella Abrasheva, Javier J. Hernández Acosta, Olda Acuna, Mohammen Addahri, Q. K. Ahmad, Pervaiz Ahmed, Alisher Aldashev, Darwish Abdulrahman Al-Emadi, Abdulrazaq Ali, Fathi Ali, Rasa Alishauskene, Harry Anastasiou, Helmut Anheier, Jose Arocena, Wil A. Art, Soo Young Auh, Taghi Azadarmaki, Ljiljana Bacevic, Richard BachiaCaruana, Erik Baekkeskov, Yuri Bakaloff, Olga Balakireva, Josip Baloban, David Barker, Miguel Basanez, Elena Bashkirova, Abdallah Bedaida, Jorge Benitez, Miloš Bešić, Jaak Billiet, Alan Black, Eduard Bomhoff, Ammar Boukhedir, Rahma Bourquia, Fares al Braizat, Lori Bramwell-Jones, Michael Breen, Ziva Broder, Thawilwadee Bureekul, Karin Bush, Harold Caballeros, Maria Silvestre Cabrera, Claudio Calvaruso, Pavel Campeaunu, Augustin Canzani, Daniel Capistrano, Giuseppe Capraro, Marita Carballo, Andres Casas, Nora Castillo, Henrique Carlos de O. de Castro, Chih-Jou Jay Chen, Pi-Chao Chen, Edmund W. Cheng, Pradeep Chhibber, Mark F. Chingono, Hei-yuan Chiu, Vincent Chua, Constanza Cilley, Margit Cleveland, Mircea Comsa, Munqith Dagher, Núria Segués Daina, Andrew P. Davidson, Herman De Dijn, Pierre Delooz, Nikolas Demertzis, Ruud de Moor, Carlos Denton, Xavier Depouilly, Peter J. D. Derenth, Abdel Nasser Djabi, Karel Dobbelaere, Hermann Duelmer, Anna Mia Ekstroem, Javier Elzo, Maria Fernanda Endara, Yilmaz Esmer, Paul Estgen, Marim Fagbemi, Tony Fahey, Nadjematul Faizah, Tair Faradov, Roberto Stefan Foa, Michael Fogarty, Georgy Fotev, Juis de Franca, Morten Frederiksen, Aikaterini Gari, Ilir Gedeshi, James Georgas, C. Geppaart, Bilai Gilani, Mark Gill, Timothy Gravelle, Stjepan Gredlj, Renzo Gubert, Linda Luz Guerrero, Peter Gundelach, David Sulmont Haak, Rabih Haber, Christian Haerpfer, Abdelwahab Ben Hafaiedh, Jacques Hagenaars, Loek Halman, Mustafa Hamarneh, Tracy Hammond, Sang-Jin Han, Elemer Hankiss, Olafur Haraldsson, Stephen Harding, Mari Harris, Mazen Hassan, Pierre Hausman, Bernadette C. Hayes, Gordon Heald, Ricardo

Manuel Hermelo, Camilo Herrera, Felix Heunks, Virginia Hodgkinson, Hanh Hoang Hong, Nadra Muhammed Hosen, Joan Rafel Mico Ibanez, Kenji Iijima, Kenichi Ikeda, Fr. Joe Inganuez, Ljubov Ishimova, Wolfgang Jagodzinski, Meril James, Aleksandra Jasinska-Kania, Will Jennings, Anders Jenssen, Guðbjörg Jónsdóttir, Fridrik Jonsson, Dominique Joye, Stanislovas Juknevicius, Salue Kalikova, Tatiana Karabchuk, Kieran Kennedy, Jan Kerkhofs S.J., Kimmo Ketola, Nail Khaibulin, J. F. Kielty, Hans-Dieter Kilngemann, Johann Kinghorn, Kseniya Kizilova, Renate Kocher, Joanna Konieczna, Sokratis Koniordos, Hennie Kotze, Hanspeter Kriesi, Sylvia Kritzinger, Miori Kurimura, Zuzana Kusá, Marta Lagos, Bernard Lategan, Francis Lee, Grace Lee, Michel Legrand, Carlos Lemoine, Noah LewinEpstein, Vladymir Joseph Licudine, Ruud Lijkx, Juan Linz, Ola Listhaug, Jinyun Liu, Leila Lotti, Susanne Lundasen, Toni Makkai, Brina Malnar, Heghine Manasyan, Robert Manchin, Mahar Mangahas, Mario Marinov, Mirosława Marody, Carlos Matheus, Robert Mattes, Ian McAllister, Nathalie Mendez, Rafael Mendizabal, Tianguang Meng, Jon Miller, Felipe Miranda, Mansoor Moaddel, Mustapha Mohammed, Jose Molina, Daniel E. Moreno Morales, Alejandro Moreno, Gaspar K. Munishi, Naasson Munyandamutsa, Kostas Mylonas, Neil Nevitte, Chun Hung Ng, Simplice Ngampou, Jaime Medrano Nicolas, Juan Diez Nicolas, Dionysis Nikolaou, Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann, Pippa Norris, Elone Nwabuzor, Stephen Olafsson, Muzzafar Olimov, Saodat Olimova, Francisco Andres Orizo, Magued Osman, Merab Pachulia, Christina Paez, Alua Pankhurst, Dragomir Pantic, Juhani Pehkonen, Paul Perry, E. Petersen, Antoanela Petkovska, Doru Petruti, Thorleif Pettersson, Pham Minh Hac, Pham Thanh Nghi, Timothy Phillips, Gevork Pogosian, Eduard Ponarin, Lucien Pop, Bi Puranen, Ladislav Rabusic, Andrei Raichev, Botagoz Rakisheva, Alice Ramos, Sonia Ranincheski, Anu Realo, Tim Reeskens, Jan Rehak, Helene Riffault, Ole Riis, Ferruccio Biolcati Rinaldi, Angel Rivera-Ortiz, Nils Rohme, Catalina Romero, Gergely Rosta, David Rotman, Victor Roudometof, Giancarlo Rovati, Samir Abu Ruman, Andrus Saar, Erki Saar, Aida Saidani, Pepita Batalla Salvadó, Ratchawadee Sangmahamad, Rajab Sattarov, Vivian Schwarz, Paolo Segatti, Rahmat Seigh, Tan Ern Ser, Sandeep Shastri, Shen Mingming, Jill Sheppard, Musa Shteivi, Renata Siemienska, Richard Sinnott, Alan Smith, Natalia Soboleva, Ahmet Sozen, Michèle Ernst Stähli, Gerry Stocker, Jean Stoetzel, Kancho Stoichev, Marin Stoychev, Katarina Strapcová, John Sudarsky, Edward Sullivan, Ni Wayan Suriastini, Marc Swyngedouw, Tang Ching-Ping, Farooq Tanwir, Jean-Francois Tchernia, Kareem Tejumola, Jorge Villamor Tigno, Noel

Timms, Larissa Titarenko, Miklos Tomka, Alfredo Torres, Niko Tos, Istvan Gyorgy Toth, Jorge Aragón Trelles, Joseph Troisi, Ming-Chang Tsai, Tu Su-hao, Claudiu Tufis, Samo Uhan, Jorge Vala, Andrei Vardomatskii, Nino Veskovic, Amaru Villanueva, Manuel Villaverde, David Voas, Bogdan Voicu, Malina Voicu, Liliane Voye, Richard M. Walker, Alan Webster, Friedrich Welsch, Christian Welzel, Meidam Wester, Chris Whelan, Christof Wolf, Stan Wong, Robert Worcester, Seiko Yamazaki, Dali Yang, Jie Yang, Birol Yesilada, Ephraim Yuchtman-Yaar, Josefina Zaiter, Catalin Zamfir, Margarita Zavadskaya, Brigita Zepa, Nursultan Zhamgyrchiev, Yang Zhong, Ruta Ziliukaite, Ignacio Zuasnabar, and Paul Zulehner.

The WVS and EVS data used in this book consists of 423 surveys carried out in successive waves from 1981 to 2020 in 112 countries and territories containing over 90 percent of the world’s population.1 Building on the EuroBarometer surveys founded by Jacques-Rene Rabier, Jan Kerkhofs and Ruud de Moor organized the EVS and invited me to organize similar surveys in other parts of the world, which led to the founding of the WVS. Jaime Diez Medrano has done a superb job in archiving both the WVS and the EVS datasets and making them available to hundreds of thousands of users, who have analyzed and downloaded the data from the WVS and EVS websites.

I am grateful to Jon Miller, Arthur Lupia, Kenneth Kollman, and other colleagues at the University of Michigan for comments and suggestions. I also am grateful to Anna Cotter, Yujeong Yang, and Anil Menon for superb research assistance, and I gratefully acknowledge support from the U.S. National Science Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the foreign ministries of Sweden and the Netherlands, each of which supported fieldwork for the WVS in a number of countries where funding from local sources was unavailable. I also thank the Russian Ministry of Education and Science for a grant that made it possible to found the Laboratory for Comparative Social Research at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow and St. Petersburg, and to carry out the WVS in Russia and several Soviet successor countries. Finally, I am grateful to the University of Michigan’s Amy and Alan Loewenstein Professorship in Democracy and Human Rights, which supported research assistance for this work.

1 The Shift from Pro-Fertility Norms to Individual-Choice Norms

Secularization has recently accelerated in most countries, for reasons inherent in the current phase of modernization. This book tests this claim against empirical evidence from surveys carried out from 1981 to 2020, in over 100 countries containing more than 90 percent of the world’s population and covering all major cultural zones. This chapter gives an overview of the book’s findings. The empirical evidence is presented in subsequent chapters.

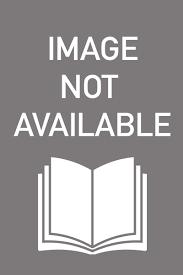

Secularization recently accelerated. Not long ago, Norris and Inglehart (2004/2011) analyzed religious change in 49 countries from which a substantial time series of survey evidence was available from 1981 to 2007. (These countries contain 60 percent of the world’s population.)1 They found that the publics of 33 out of 49 countries had become more religious during this period. When these same 49 countries were reexamined in 2020, the trend toward rising religiosity had reversed itself. As Figure 1.1 indicates, in 2020 the publics of only six countries showed net gains in religiosity since 2007; one showed no significant change; and the publics of 42 countries had become less religious from 2007 to 2020.

For many years, the U.S. has been cited as the key piece of evidence demonstrating that even highly modernized countries can be strongly religious. But since 2007, the U.S. has been secularizing more rapidly than any other country for which we have data. Its level has fallen substantially by virtually every measure of religiosity, and by one widely recognized criterion it now ranks as the 12th least religious country in the world.

There are several reasons secularization is accelerating. One generally overlooked cause springs from the fact that, for many centuries, a coherent set of pro-fertility norms* evolved in most countries that assigns women the role of producing as many children as possible and discourages divorce,

* Governments sometimes adopt pro-natalist policies intended to raise the country’s birth rate. Pro-fertility norms are cultural traditions with strong moral connotations, often backed by religion.

Religion’s Sudden Decline. Ronald F. Inglehart, Oxford University Press (2021). © Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197547045.003.0001

Figure 1.1 Countries showing increasing and decreasing religiosity over two time periods.

Source: Responses to question “How important is God in your life?” asked in the World Values Survey and European Values Study. See Figures 7.3, 7.4, and 7.5 for fuller details.

abortion, homosexuality, contraception, and any other form of sexual behavior not linked with reproduction.

Virtually all major world religions instill pro-fertility norms, which helped societies survive when facing high infant mortality and low life expectancy. These norms require people to suppress strong natural urges but are no longer needed for societal survival—and are rapidly giving way to individual-choice norms, supporting gender equality and tolerance of divorce, abortion, and homosexuality. Pro-fertility norms are so closely linked with traditional religious worldviews that abandoning them undermines religiosity. This rapid change of basic societal norms creates a polarization between those with traditional worldviews and those with modern worldviews, producing bitter political conflict.

Rising support for individual-choice norms is not the only factor driving secularization. Reactions against religious fundamentalists’ embrace of xenophobic authoritarian politicians, against the Roman Catholic Church’s long history of covering up child abuse, and against terrorism by religious extremists, all seem to be contributing to secularization. In the U.S., for example, since the 1990s the Republican Party has sought to win support by adopting the Christian conservative position on sexual morality and opposition to same-sex marriage and abortion and closed ranks behind President Donald Trump’s authoritarian xenophobic policies. Some critics argued that this didn’t just attract religious voters—it was also driving

social liberals, especially young ones, away from religion (Hout & Fischer, 2002). Initially, this claim seemed dubious because there is a large and wellfounded literature on how religion shapes politics. A person’s religion was generally so stable that it was almost a genetic attribute. But as religion weakens, the dominant causal flow can change direction, with one’s political views increasingly shaping one’s religious outlook. Thus, using General Social Survey panel data, Hout and Fischer (2014) found that people were not becoming more secular and then moving toward liberal politics to fit their new religious identity; instead, they found that the main causal direction runs from politics to religion. Younger respondents were disproportionately likely to desert the Republican Party because of a growing desire for personal autonomy, particularly concerning sex, abortion, and drugs. As another observer recently put it, “Politics can drive whether you identify with a faith, how strongly you identify with that faith, and how religious you are . . . and some people on the left are falling away from religion because they see it as so wrapped up with Republican politics” (Margolis, 2018). A number of factors (including some nation-specific ones) help explain the recent worldwide decline of religion—but the rise of individual-choice norms seems to be the most widely applicable one.

This book focuses on one important aspect of social change: the changing role of religion. Another book, Cultural Evolution: People’s Motivations Are Changing, and Changing the World (R. F. Inglehart, 2018), provides a broader framework for understanding how economic and technological development are reshaping the world, analyzing changes in basic values concerning politics, economic inequality, gender roles, child-rearing norms, religion, willingness to fight for one’s country, and the implications for society of the rise of artificial intelligence. It interprets these developments from the perspective of evolutionary modernization theory.

Well into the 20th century, leading social thinkers held that religious beliefs would decline as scientific knowledge and rationality spread throughout the world. The worldviews of most scientists were indeed transformed by the spread of scientific knowledge, but religion persisted among the general public. In recent years, the dramatic activism of fundamentalist movements in many countries and the religious revival in former communist countries have made it obvious that religion is not disappearing, and even led to claims of a global resurgence of religion.

An influential challenge to the secularization thesis, religious markets theory, argues that established churches become complacent

monopolies—but competition between churches brings high levels of religious participation (Finke & Iannaccone, 1993; Stark & Bainbridge, 1985). Still another perspective, the religious individualization thesis, claims that the declining influence of churches does not represent a declining role for religion; people are simply freeing themselves from institutional guidelines and making their own choices, with subjective forms of religion replacing institutionalized ones.

Norris and Inglehart (2004/2011) propose an alternative to all three versions of secularization theory, arguing that insecure people need the psychological support and reassuring predictability of traditional religion’s absolute rules—but that as survival becomes more secure, this need is reduced. They present evidence that industrialization, urbanization, growing prosperity, and other aspects of modernization are conducive to secularization. Nevertheless, they point out, the world as a whole now has more people with traditional religious views than it did 50 years ago because, while virtually all major religions encourage high birth rates, secularization has a strong negative impact on them. Today, virtually all high-income societies are relatively secular, and their birth rates have fallen below the population-replacement level—but low-income societies remain religious and are producing large numbers of children. Modernization brings secularization, but contrasting birth rates maintain the number of believers—at least for the time being, since birth rates are falling even in low-income countries.

Despite differential fertility rates, secularization has persisted, and has recently accelerated in much of the world, largely because of two related cultural shifts:

1. Insecure people need the predictability and absolute rules of traditional religion—and throughout history, survival has usually been insecure. But modernization brings greater prosperity, lower rates of violence, and improved public health, reducing the demand for religion. The second factor has accelerated this trend.

2. A shift from pro-fertility norms to individual-choice norms. The world’s major religions inculcated pro-fertility norms in order to replace the population when facing high infant mortality and low life expectancy. These norms require strong self-denial, but rising life expectancy and sharply declining infant mortality have made these norms no longer necessary for societal survival. After an intergenerational time lag, profertility norms, emphasizing traditional gender roles and stigmatizing

any sexual behavior not linked with reproduction, are giving way to individual-choice norms supporting gender equality and tolerance of divorce, abortion, and homosexuality. This is eroding traditional religious worldviews.

Instead of attributing secularization to the advance of scientific knowledge or to modernization in general— both of which imply that secularization is a universal and unidirectional process—evolutionary modernization theory argues that secularization reflects rising levels of security. It occurs in countries that have attained high levels of existential security and can move in reverse if societies experience prolonged periods of declining security.

Moreover, evolutionary modernization theory recognizes that modernization is path-dependent, with a given country’s level of religiosity reflecting its historical heritage. For example, though most countries’ historically dominant belief system was religious, Confucian-influenced societies were shaped by a secular belief system that made their starting level of religiosity lower than that of other countries—where it remains today.

Security is psychological as well as physical. The collapse of a belief system can reduce people’s sense of security as much as war or economic hardship does. Religion traditionally compensated for low levels of economic and physical security by providing assurance that the world was in the hands of an infallible higher power who ensured that, if one followed his rules, things would ultimately work out for the best. Marxist ideology replaced religion for many people, assuring its believers that history was on their side and that their cause would ultimately triumph. The collapse of Marxist belief systems led to a massive decline of subjective well-being among the people of the former Soviet Empire, a decline that lasted for decades, leaving an ideological vacuum to be filled by rising religiosity and nationalism.

Finally, though secularization normally occurs at the pace of intergenerational population replacement, it can reach a tipping point where the dominant opinion shifts, and the forces of conformism and social desirability start to favor the outlook they once opposed—producing rapid cultural change. Younger and better-educated groups in high-income countries have reached this point.

Alexander et al. (2016) argue that the legalization of abortion and samesex marriage are part of a long-term trend toward giving people a wider range of choice in all aspects of life—but that until recently, religion generally managed to block this trend in one important domain, that of sexual

freedom. They suggest that more secure living conditions, from rising life expectancy to broader education, have led to cultural changes that allow a wider range of choices. This trend has begun to spill over into the realm of sexual freedom, where, until recently, religious norms and institutions were able to resist the spread of free choice. They support these claims with a broad array of evidence. Since the Enlightenment, the struggle for human emancipation—from the abolition of slavery to the recognition of human rights—has been a defining feature of modernization (Markoff, 1996; Pinker, 2011). This struggle virtually always aroused resistance from reactionary forces (Armstrong, 2001; Weinberg & Pedahzur, 2004). Nevertheless, social movements and civil society groups around the world have continued to campaign for human emancipation, pushing its frontier farther and farther (Carter, 2012; Clark, 2009). This frontier has reached the domain of individual-choice norms, where religion until recently had largely succeeded in blocking the spread of free choice (Frank et al., 2010; Kafka, 2005; Knudsen, 2006). The recent legalization of abortion and same-sex marriage in many countries constitutes a breakthrough at society’s most basic level: its ability to reproduce itself. These changes are driven by growing mass support for sexual self-determination, which is part of an even broader trend toward greater emphasis on freedom of choice in all aspects of life. Support for free choice in the realm of sexual behavior has emerged relatively recently and is now moving rapidly, but it remains hotly contested by conservative social forces, especially religion.

Throughout history, sexual reproduction has been an aspect of life in which religious tradition has most successfully blocked the spread of free choice. The rise of free choice in this domain constitutes an evolutionary breakthrough in the development of moral systems (Alexander et al., 2016). Today, Western countries’ social norms are profoundly different from those of the postwar era. In 1945, homosexuality was still criminal in most Western countries; it is now legal in virtually all of them. In the postwar era, both church attendance and birth rates were high; today, church attendance has declined drastically and human fertility rates have fallen below the population-replacement level.

Although deep-seated norms limiting women’s roles and stigmatizing homosexuality persisted from biblical times to the 20th century, the World Values Survey and the European Values Study show rapid changes from 1981 to 2020 in high-income countries, with growing acceptance of gender equality and LGBTQ people and a rapid decline of religiosity. In low-income

societies, tolerance of abortion, homosexuality, and divorce remains low, and conformist pressures inhibit people from expressing tolerance. And in most former communist countries, religion grew rapidly after 1990, filling the vacuum left by the collapse of Marxist belief systems—and encouraging a return to traditional pro-fertility norms.

But intergenerational population replacement has made individualchoice norms increasingly acceptable—initially among the younger and better-educated strata of high-income societies. Experimentation with new norms occurs, and when it seems successful, spreads—with the prevailing outlook gradually shifting from rejection to acceptance of the new norms. As attitudes become more tolerant, more gays and lesbians come out. Growing numbers of people realize that some of the people they know and like are homosexual, leading them to become more tolerant and encouraging more LGBTQ people to come out, in a positive feedback loop (Andersen & Fetner, 2008; R. Inglehart and Welzel, 2005).

Religiosity and the Shift from Pro-Fertility Norms to Individual-Choice Norms

Religion is not an unchanging aspect of human nature. The belief in a God who is concerned with human moral conduct becomes prevalent only with the emergence of agricultural societies. Concepts of God have continued to evolve since biblical times, from an angry tribal God who was placated by human sacrifice and demanded genocide, to a benevolent God whose laws applied to all humanity. Thousands of societies have existed, most of which are now extinct. Virtually all of them had high infant mortality rates and low life expectancy, making it necessary to produce large numbers of children in order to replace the population. And virtually all societies that survived for long inculcated pro-fertility norms limiting women to the roles of wife and mother and stigmatizing divorce, abortion, homosexuality, masturbation, and any other sexual behavior not linked with reproduction (Nolan & Lenski, 2015). From biblical times to the 20th century, some societies have advocated celibacy, but these societies have disappeared. Virtually all major religions that survive today instill gender roles and reproductive norms that encourage women to cede leadership roles to men and to bear and raise as many children as possible—stigmatizing any sexual behavior not linked with reproduction.

Throughout history, religion has helped people cope with survival under insecure conditions. Facing starvation, violence, or disease, it assured people that the future was in the hands of an infallible god and that if they followed his rules, things would work out. This gave people the courage to cope with threatening and unpredictable situations rather than give way to despair, increasing their chances of survival. Having a clear belief system is conducive to physical and mental health, and religious people tend to be happier than nonreligious people (R. F. Inglehart, 2018, Chapter 8). The belief system need not be religious; Marxism once provided a clear belief system and hope for the future for many people—but when it collapsed, subjective well-being collapsed along with it.

Since World War II, survival has become increasingly secure for a growing share of the world’s population. Income and life expectancy have been rising and poverty and illiteracy have been declining throughout the world since 1970, and crime rates have been declining for many decades. The world is now experiencing the longest period without war between major powers in recorded history. This, together with the postwar economic miracles and the emergence of the welfare state, produced conditions under which a large share of those born since 1945 in Western Europe, North America, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand grew up taking survival for granted, bringing intergenerational shifts toward new, more permissive values.

Most societies no longer require high fertility rates. Infant mortality has fallen to a tiny fraction of its 1950 level. Effective birth control technology, labor- saving devices, improved child care facilities, and low infant mortality make it possible for women to have children and full-time careers. Traditional pro- fertility norms are giving way to individualchoice norms that allow people a broader range of choice in how to live their lives.

Pro-fertility norms have high costs. Forcing women to stay in the home and gays and lesbians to stay in the closet requires severe repression. Once high human fertility rates are no longer needed, there are strong incentives to move away from pro-fertility norms—which usually means moving away from religion. As this book demonstrates, norms concerning gender equality, divorce, abortion, and homosexuality are changing rapidly. Young people in high-income societies are increasingly aware of the tension between religion and individual-choice norms, motivating them to reject religion. Beginning in 2010, secularization has accelerated sharply.

A long time lag intervened between the point when high fertility rates were no longer needed to replace the population and the point when these changes occurred. People hesitate to give up familiar norms governing gender roles and sexual behavior. But when a society reaches a sufficiently high level of economic and physical security that younger birth cohorts grow up taking survival for granted, it opens the way for an intergenerational shift from profertility norms to individual-choice norms that encourages secularization. Although basic values normally change at the pace of intergenerational population replacement, the shift from pro-fertility norms to individual-choice norms has reached a tipping point at which conformist pressures reverse polarity and are accelerating changes theyonce resisted.

Different aspects of cultural change are moving at different rates. In recent years, high-income countries have been experiencing massive immigration by previously unfamiliar groups. They have also been experiencing rising inequality and declining job security, for reasons linked with the winnertakes-all economies of advanced knowledge societies. The causes of rising inequality are abstract and poorly understood, but immigrants can be clearly visible, making it easy for demagogues to blame them for the disappearance of secure, well-paid jobs. In fact, immigrants are disproportionately likely to create new jobs; for instance, about half of the entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley are foreign-born. But psychological reactions do not necessarily reflect rational analysis. Moreover, many recent immigrants are Muslim, and hostility to them is compounded by highly publicized Islamic terrorism. Accordingly, though acceptance of gays and lesbians and gender equality has risen in most developed countries, xenophobia remains widespread. Coupled with a reaction against rapid cultural change, this has enabled anti-immigrant parties to win a large share of the vote in many countries.

Religion became pervasive because it was conducive to societal survival in many different ways. It minimized internal conflict by establishing rules against theft, deceit, and murder and other forms of violence, encouraged norms of sharing, and instilled pro-fertility norms that encouraged reproduction rates high enough to replace the population. Religions were not the only belief system that could accomplish this. In much of East Asia, a secular Confucian belief system became widespread that did not rely on a moral God who imposed rewards and punishments in an afterlife; the Confucian bureaucracy provided rewards and punishments in this world, but they were linked with a set of duties that supported obedience to the

state and included the duty to produce a male heir, which encouraged pro-fertility norms.

But pro-fertility norms usually are closely linked with religion. In societies that survive for long, religion imposes strong sanctions on anyone who violates them. Support for pro-fertility norms and religiosity is strongest in insecure societies, especially those with high infant mortality rates, and weakest in relatively secure societies. Pro-fertility norms require people to suppress strong drives, creating a built-in tension between them and individual-choice norms. Throughout most of history, natural selection helped impose pro-fertility norms, because societies that lacked them tended to die out.

In Darwin’s Cathedral, David Sloan Wilson (2002; cf. D. S. Wilson, 2005) proposes an evolutionary theory of religion, holding that religions are best understood as “superorganisms” adapted to succeed in evolutionary competition against others. From this perspective, morality and religion are biologically and culturally evolved adaptations that enable human groups to function effectively. When Wilson first proposed this theory, almost no widely respected biologist believed in group selection. Since the 1960s, the selfish gene model had dominated the field, holding that evolution could take place only at the individual level (Dawkins, 1977). For a society to function, its members must perform services for each other. But members who behave for the good of the group often put themselves at a disadvantage compared with more selfish members of that group, so how can prosocial behaviors evolve? The solution that Darwin proposed in The Descent of Man (1871) is that groups containing mostly altruists have a decisive advantage over groups containing mostly selfish individuals, even if selfish individuals have an advantage over altruists within each group.

This might have provided a basis for understanding the evolution of social behavior, but during the 1960s evolutionary biologists were convinced that between-group selection is virtually always weaker than within-group selection. Group selection became a pariah concept, and inclusive fitness theory, evolutionary game theory, and selfish gene theory were all developed to explain the evolution of apparently altruistic behavior in individualistic terms, without involving group selection.

But Wilson persisted, marshaling a variety of evidence demonstrating how religions have enabled people to achieve, through collective action, things that they could not have done alone. Today, the concept that natural selection takes place at both individual and group levels is widely accepted. Its triumph

has been so complete that the founder of sociobiology himself, E. O. Wilson (no relation to David), abandoned his original focus on gene-centered evolution to adopt the view that natural selection takes place at both the level of groups and the level of genes. The two Wilsons even became co-authors (D. S. Wilson & Wilson, 2007). Recent research does not show that betweengroup selection always prevails against within-group selection, but it does show that between-group selection is often important.

Until recently, natural selection helped impose pro-fertility norms. But a growing number of societies have attained high existential security, long life expectancy, and low infant mortality, making pro-fertility norms no longer necessary for societal survival and opening the way for a shift to individualchoice norms. Normally there is a substantial time lag between changing societal conditions and cultural change. The norms one grows up with are familiar and seem natural, and abandoning them brings stress and anxiety, so deep-rooted norms usually change slowly, largely through intergenerational population replacement.

Throughout most of history, religious institutions were able to impose pro-fertility norms. But the causal relationship is reciprocal and the dominant direction can be reversed: if pro-fertility norms come to be seen as outmoded and repressive, their rejection also brings rejection of religion. In societies where support for pro-fertility norms is giving way to individualchoice norms, we find declining religiosity. In societies where religion remains strong, little or no change in pro-fertility norms is taking place. But religiosity has been growing in some societies, particularly in formerly communist societies, and there it has been accompanied by growing emphasis on pro-fertility norms and declining acceptance of individual-choice norms.

The declining need for pro-fertility norms opened the way for gradual secularization, with the young being most open to change. Consequently, in high-income countries the younger birth cohorts are much less religious than their older compatriots; among those born between 1894 and 1903, 42 percent said that God was very important in their lives; among those born between 1994 and 2003, only 11 percent said this.2 These age differences do not reflect some universal aspect of the human life cycle, through which people grow more religious as they age; such age differences are virtually absent in Muslim-majority countries where little cultural change is occurring. But in high-income countries, we find large and enduring differences between the religiosity of older and younger birth cohorts, and the young do not get more religious as they age.

The Recent Acceleration of Secularization in High-Income Countries

From 1981 to 2020, the publics of most countries showed rising acceptance of individual-choice norms. This trend reflected a society’s level of existential security: among the high-income countries for which time series data is available, 23 of the 24 countries showed rising acceptance of individual-choice norms. But this trend was not limited to high-income countries: the publics of 36 other countries, including seven in Latin America and some relatively secure ex-communist countries, also showed rising acceptance of these norms. And the publics of several Muslimmajority countries have moved from extremely low to slightly higher levels of acceptance. But the publics of some countries became less tolerant of individual-choice norms; most of these were less secure ex-communist countries, where religiosity was rising to fill the vacuum left by the collapse of Marxist belief systems.

Today, secularization is largely driven by the shift from pro-fertility norms to individual-choice norms. The two are closely linked. Countries whose publics emphasize pro-fertility norms tend to be strongly religious, while countries whose publics emphasize individual-choice norms are much less religious. As one might expect, the publics of high-income countries rank highest on individual-choice norms, and—though they once were far more religious than the people of communist countries— today they are among the world’s least religious peoples. At the other end of the spectrum, the publics of Muslim-majority countries and low-income countries in Africa and Latin America are the world’s most religious people and adhere most strongly to pro-fertility norms.

In contrast to the past, the publics of virtually all high-income countries now rank high on support for individual-choice norms and low on religiosity. This reflects the fact that individual-choice norms and religiosity have a reciprocal causal connection. Throughout most of history, the causal flow moved mainly from religion to social norms, enforcing strong taboos on any sexual behavior not linked with reproduction and limiting women to reproductive roles. But in the 21st century, the main causal flow has begun to move in the opposite direction, with the publics of a growing number of countries rejecting traditional pro-fertility norms and consequently becoming less religious.

How Secularization Accelerates

Our theory implies that (a) in societies where religion remains strong, little or no change in pro-fertility norms will take place; (b) in societies where religiosity is growing, we will find growing support for pro-fertility norms; and (c) in societies where support for pro-fertility norms is rapidly giving way to individual-choice norms, we will find declining religiosity.

Data is available from each of these three types of countries: in Muslimmajority countries, religion remains strong; in most former communist countries, religiosity has grown since the collapse of communism; and in virtually all high-income countries, we find declining religiosity.

Although intergenerational population replacement involves long time lags, cultural change can reach a tipping point at which new norms become dominant. Conformism and social desirability effects then reverse polarity: instead of retarding the changes linked with intergenerational population replacement, they accelerate them, bringing unusually rapid cultural change. In the shift from pro-fertility norms to individual-choice norms, this point has been reached in a growing number of countries, starting with the younger and more secure strata of high-income societies.

Almost all high-income societies have now reached the tipping point where the balance shifts from pro-fertility norms being dominant to individual-choice norms becoming dominant. In 1981, majorities of the public of every country for which we have data endorsed pro-fertility norms—generally by wide margins. But a shift toward individual-choice norms was occurring in high-income countries. In 1990, the Swedish public was the first to cross the tipping point where support for individual-choice norms outweighed support for pro-fertility norms; in subsequent years, the Swedes were followed by the publics of virtually all other high-income countries, with the American public crossing this tipping point only recently.

In high-income countries, support for individual-choice norms is stronger among the young than among the old. In the most recent available survey, the oldest cohort (born before 1933) was still below this tipping point, but the youngest cohort (born since 1994) was far above it. By contrast, the publics of all but the most secure ex-communist countries became more religious and less supportive of individual-choice norms. And the publics of all 18 Muslim-majority countries for which data is available remained far below the tipping point at every time point since 1981, continuing to be strongly