1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: González, Gabriela, author.

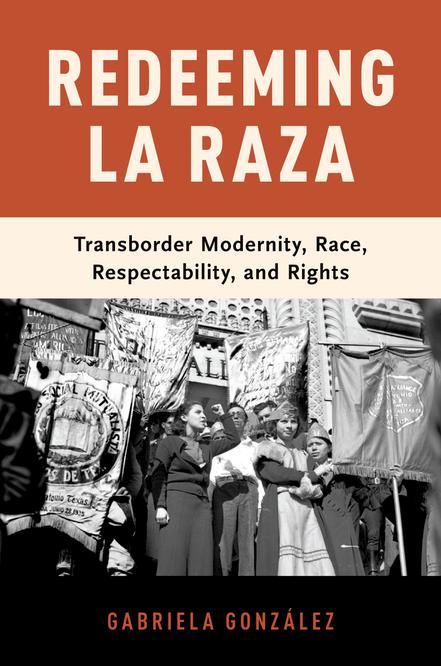

Title: Redeeming La Raza : transborder modernity, race, respectability, and rights / Gabriela González.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017056469 (print) | LCCN 2018017172 (ebook) | ISBN 9780199914159 (Updf) | ISBN 9780190902155 (Epub) | ISBN 9780190909628 (paperback) | ISBN 9780199914142 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Mexican Americans—Texas—Politics and government—20th century. | Mexican Americans—Political activity—Texas. | Mexican Americans—Texas—Biography. | Mexicans—Texas—History—20th century. | Transnationalism—Political aspects— Texas—History—20th century. | Texas, South—Politics and government—20th century. | Mexican-American Border Region—Politics and government—20th century.

Classification: LCC F395.M5 (ebook) | LCC F395.M5 G665 2018 (print) | DDC 323.1168/720764—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017056469

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Paperback printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

Hardback printed by Bridgeport National Bindery, Inc., United States of America

Parts of this book have been adapted from “Carolina Munguía and Emma Tenayuca: The Politics of Benevolence and Radical Reform” in Frontiers: A Journal of Women’s Studies, Vol. 24, No. 2/3, 2003, pp. 200–229, courtesy of the University of Nebraska Press, and “Jovita Idar: The Ideological Origins of a Transnational Advocate for La Raza,” in Texas Women: Their Histories, Their Lives (2015), edited by Elizabeth Hayes Turner, Stephanie Cole, and Rebecca Sharpless, courtesy of University of Georgia Press.

I dedicate this book to my parents, Jorge G. and María B. González, and to my husband and daughter, Roger and Isabella Landeros, with much LOVE.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments ix

Note on Usage xv

Introduction: Redeeming La Raza in the World of Two Flags Entwined 1

PART I MODERNIZING MEXICO AND THE BORDERLANDS, 1900–1929

1. Social Change, Cultural Redemption, and Social Stability: The Political Strategies of Gente Decente Reform 15

2. Masons, Magonistas, and Maternalists: Liberal, Anarchist, and Maternal Feminist Thought within a Local/Global Nexus 51

3. Crossing Borders to Rebirth the Nation: Leonor Villegas de Magnón and the Mexican Revolution 82

PART II BORDERLANDS MEXICAN AMERICANS IN MODERN TEXAS, 1930– 1950

4. “Todo Por la Patria y el Hogar” (All for Country and Home): The Transnational Lives and Work of Rómulo Munguía and Carolina Malpica de Munguía 111

5. La Pasionaria (the Passionate One): Emma Tenayuca and the Politics of Radical Reform 145

6. Struggling against Jaime Crow: LULAC, Gente Decente Heir to a Transborder Political Legacy 167

Conclusion: “La Idea Mueve” (The Idea Moves Us): Why Cultural Redemption Matters 190

Notes 197 Bibliography 223 Index 249

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I begin by thanking the civil and human rights activists I write about in this book and their family members who granted me oral history interviews. At the beginning of the semester I sometimes ask my UTSA students to look around and recognize the great diversity represented in our classroom. Then I encourage them to pay attention to the men and women in history who worked to make diverse classrooms like ours possible. The genesis of this book started with my desire to pay attention to transborder activists who shared a vision for a just and equitable society and pursued it by using their privileges to take on the challenges they faced.

This project, or at least part of it, started while I was a master’s student at the University of Texas at San Antonio. I thank fellow graduate students and friends, Joe Belk, Dave Hansen and Sandy Rubinstein Peterson for their kindness and moral support during those early days when I was fumbling through the process of learning how to become a historian. In classes taught by Antonio Calabria, Gilberto Hinojosa, David Johnson, Juan Mora-Torres, Cynthia Orozco, Linda Pritchard, Jack Reynolds, Jim Schneider and Linda Schott I dove into local, state, national, and global histories, relishing each opportunity to place my research interests within broader contexts. In the mid-1990s, I was not yet using such terms as transborder and transnational, yet my awareness of the historical phenomena that these concepts describe grew alongside my research agenda. An internship at the Institute of Texan Cultures, organizing the Spanish colonial history files of then UT Austin professor, Antonia Castañeda, further shaped my intellectual development, introducing me to Chicana history. A class titled “Hispanics in the United States” taught by UTSA Visiting Professor Cynthia Orozco introduced me to Latina/o history. The ideas for this study germinated at the intersection of that internship with Antonia, Cynthia’s course, and an independent study focused on the theme of women’s voluntary associations supervised by Linda Schott. My thanks to Linda for introducing me to

comparative women’s history and for supporting my decision to pursue a project focused on the life and work of Carolina Malpica de Munguía; to Cynthia for her comparative Latinas/os history course instruction and for introducing me to the Munguía Family papers and the LULAC archives at UT Austin; and to Antonia for inspiring me to interrogate power dynamics and study the ways in which naturalizing inequities breeds and sustains injustice. My thanks also to Antonia for introducing me to the human and civil rights work of San Antonio’s Esperanza Peace and Justice Center led by Graciela Sánchez, which continues in the tradition of consciousness-raising, questioning of power, and grassroots activism.

Besides my internship, I also had the privilege of working as a research assistant for Professor Jack Reynolds in his Camino Real project and as a graduate assistant for the Center for the Study of Women and Gender directed by Professor Linda Schott which was housed in the Dean’s office, where I got to interact with Associate Dean Linda Pritchard. I am grateful for the guidance I received from these individuals who mentored me and encouraged me to pursue a PhD.

At Stanford University, my good fortune continued thanks to the dedicated mentoring I received from my primary advisors, Professors Albert Camarillo and Estelle Freedman. Al and Estelle brought a wealth of expertise and experience into their teaching and cultivated a sense of intellectual community in the classroom and beyond through university centers and institutes whose programming enhanced my understanding of issues of race, class, gender, and sexuality. From Professor George Frederickson, I learned about the role that ideologies play in shaping political philosophies and practices. During my time at Stanford, Professor Richard White joined the faculty. A couple of conversations with him about my work helped me to properly identify it as transborder and transnational history. Three teaching assistantships helped me develop my teaching skills and added to my understandings of related historiographies. I am grateful to Al and George who co-taught a comparative course on race and ethnicity in the United States. Among other things, from this experience I learned that racism and ethnocentrism in this country developed alongside democratic principles enshrined in founding documents. In my second TAship, I worked with Professor David Kennedy in his course on twentieth century US history. One of the things I picked up from his lectures was the importance of the 1930s and 1940s because of the Great Depression and World War II and more fundamentally, the transformative nature of these events in American life and culture. Finally, the Introduction to Asian American History course I TAed for Professor Gordan Chang helped me to reflect upon the diverse experiences within communities. In the section I led, many of my students identified as Asian American but our discussions often revealed differing levels of perceived as well as unexamined privilege and power dynamics based on phenotype, class, gender, immigrant or

citizenship status, and so forth. These were social relations I had casually noticed within ethnic Mexican communities, but something about playing the role of mediating teaching assistant, raised my level of consciousness about the internal dialogues that occur within ethnic and pan-ethnic communities.

This book has benefited from a vast secondary literature revealing multiple historiographies with plenty of intellectual cross-pollination. Rather than attempting to list all the scholars whose work this book draws insights from and risk forgetting someone, I will direct the interested reader to the notes and bibliography. Other influences have been the many scholars with whom I have served on conference panels and roundtables over the years. My thanks to conference participants who provided questions and comments on my work.

At various critical points in my career, Professor Vicki Ruíz has offered valuable advice about my work. I join the impressive list of scholars who have benefitted much from her committed mentoring and pioneering scholarship and who see her as a role model. Others who at various times have offered me advice about my career, read my work, or in some other way assisted me include: Norma E. Cantú, Stephanie Cole, Deena González, David G. Gutiérrez, Elizabeth Hayes Turner, Raquel Márquez, Marie “Keta” Miranda, Paula Moya, Cynthia Orozco, Emma Pérez, Harriett Romo, Ricardo Romo, Rodolfo Rosales, Sonia Saldívar-Hull, Stephen Pitti, George J. Sánchez, Rebecca Sharpless, Andrés Tijerina, Ruthe Winegarten, Elliot Young, and Emilio Zamora.

My Stanford cohort enriched my grad student experiences in significant ways. The diverse cultural and geographic backgrounds of Noemí García Reyes, Mónica Perales, Shana Bernstein, Shawn Gerth, Joe Crespino, Paul Herman, and my own underscored the concept of “unity in diversity” for me, because despite our differences, we rooted for each other and enjoyed each other’s company. Special thanks to Mónica, Shana, Joe, and Paul for reading sections of my dissertation and offering excellent feedback. Other wonderful friends and colleagues who made my time at Stanford enjoyable and memorable include: Magdalena Barrera, Matthew Booker, Michelle Campos, Alicia Chávez, Marisela Chávez, Roberta Chávez, Jennifer Chin, Raúl Coronado, Rachel Jean-Baptiste, Benjamin Lawrence, Dawn Mabalon, Martha Mabie Gardner, Shelley Lee, Carol Pal, Gina Marie Pitti, Stephen Pitti, Amy Robinson, Lise Sedrez, Cecilia Tsu, and Kim Warren. I am so proud of my Stanford friends for their many wonderful contributions in their respective fields. Finally, a very special thank you to Professor Richard Roberts and two members of the Department of History staff who kept the graduate students sane, Monica Wheeler and the late Gertrude Pacheco.

My work colleagues at the UTSA Department of History have also provided me with a sense of community and inspiration and several with valuable feedback on my work. My thanks to department chair Kirsten Gardner for her brilliant leadership and unwavering support and encouragement. Kirsten, you

Acknowledgments

are integrity personified. Before Kirsten, other supportive chairs included Wing Chung Ng, Jim Schneider, Jack Reynolds, and Gregg Michel. My thanks to them and to Dean Daniel Gelo for believing in the significance of my work as a teacher and scholar. Elizabeth Escobedo and I started at UTSA at the same time and became fast friends. Though she no longer works at UTSA, she remains a dear friend, and I am very proud of all she has accomplished. At the UTSA Department of History I have enjoyed the friendship and collegiality of amazing women faculty. My heartfelt thanks to Sistorians Catherine Clinton, Kirsten Gardner, Rhonda Gonzales, LaGuana Gray, Kolleen Guy, Anne Hardgrove, Catherine Komisaruk, and Catherine Nolan-Ferrell. My fellow Sistorians, know that I greatly admire your work as teachers, scholars, and engaged university citizens. Félix Almaráz, Brian Davies, Jerry González, Patrick Kelly, Andrew Konove, Gregg Michel, Wing Chung Ng, Jack Reynolds, and Omar Valerio-Jiménez have been terrific colleagues whose work I also appreciate. I am grateful for conversations and advice received from John Carr- Shanahan, Andria Crosson, Jennifer Dilley, Dave Hansen, Lesli Hicks, Dwight Henderson, Jodi Peterson, the late Patricia Thompson, and Elaine Turney.

A special thanks to all my students and advisees throughout the years. Countless classroom and office hour discussions, plus assorted faculty/student projects on many topics, including the ones addressed in this book, have enriched my teaching and research in immeasurable ways. Some of these students are currently pursuing Master’s and doctoral degrees with specializations in Chicana/o history and allied fields, while others have completed their education in these areas and are teaching in colleges and universities. This is gratifying because they are pursuing their dreams and because issues of representation matter in the classroom setting as in the rest of society. I am proud of the Latina scholars currently in the pipeline or practicing in the profession, among them Terri Castillo, Jessica Ceeko, Sandra Garza, Philis Barragan Goetz, Corina González Stout, Delilah Hernández, Nydia Martínez, Sylvia Mendoza, Laura Narváez, Patricia Portales, Lori Rodríguez, Micaela Valadez, and Vanessa Valadez.

During my time at UTSA, I have had the privilege of working with research assistants Nydia Martínez, Sandra García, Sandra Wagoner, Efraín Torres, Amber Walker and Kuba Abdul; reader/grader Gabrielle Zepeda; teaching assistants Michael Ely, Erica Valle, and Jared Gaytán; and Department of History staff members past and present, Sherrie McDonald, Cheryl Tuttle, Andrea Trease, James Vagtborg, Marcia Perales, Roschelle Kelly, Judith Quiroz, and Carrie Klein. Funding from a post-doctoral Ford Foundation fellowship, a UTSA faculty development leave, and departmental travel funds have made it possible for me to visit archives and present my work at conferences. This book could not have been written without the work of archivists and librarians at The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of

Texas, Austin; UTSA’s Institute of Texan Cultures; the Webb County Heritage Foundation; Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico, D.F.; Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M, Corpus Christi, Texas; the Stanford University Libraries; Berkeley Library, University of California; The Laredo Public Library; BlaggHuey Library, the Woman’s Collection, Texas Woman’s University, Denton, Texas; M.D. Anderson Library, University of Houston; and the National Archives in College Park, Maryland. I am especially grateful to Dr. Michael Hironymous and Margo Gutiérrez at the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Library, University of Texas, Austin, Texas and Shari Salisbury and Dr. Agnieszka Czeblakow at the UTSA John Peace Library, San Antonio, Texas.

Susan Ferber, OUP Executive Editor, has encouraged me from the earliest days when I met her while still a doctoral student at Stanford. Vicki Ruíz gave a brilliant talk on From Out of the Shadows and advised me to meet Susan and get her business card. This is an example of what I mean by Vicki being there for me during critical points in my career. Susan, too, has been a strong supporter. The first manuscript I sent to Oxford came back from reviewers with a revise and resubmit. Susan was the first person to encourage me to go for it and has helped me to navigate through a process that for first-time book authors can be daunting. She also provided excellent editorial guidance that helped me to clarify ideas and writing style while thinking deeper about the implications of my work.

At Oxford University Press, I have also had the pleasure of working with my project manager, Maya Bringe, who has been so kind and helpful, providing me with the guidance and structure I needed. The countless doings and happenings that add up to a service-oriented professional career and a full family life bring fulfillment and happiness, but they can also compete for a writer’s time and energy so having press-related deadlines and a sense of accountability to an editor is a beautiful thing. My other good fortune is working with the great copy editor, Patterson Lamb, and indexer, John Grennan. Thank you for your wonderful work.

I am also grateful to the reviewers for their generous feedback. Some of the most valuable commentary about my work and advice on how to sharpen my arguments and other such issues came from two sets of blind reviewers. Not only is this book a different book because it went through a process of multiple revisions, but I feel like a different person for having gone through it all. And in the same way I felt a deep sense of joy and gratitude once my daughter was born after a 30-hour labor, I can now happily release this book after years of gestation.

Finally, I am grateful to my family, the source of so many blessings in my life. My loving parents, Jorge G. and María B., served as my first teachers and mentors. She taught me never to give up, and he taught me how to read. They provided me with a strong foundation and always expressed faith in me. I am fortunate to still have my mami with me on earth and to have a papi angel in heaven

watching over me. My siblings, Graziela, Jorge Jr., Ira, Malcolm, and Aléxiz were the original BFFs (best friends forever) in my life. Through the ups and downs of life, love and friendship remain. It is gratifying to see my siblings happy, and I thank their life partners, past and present, for bringing joy into their lives and blessing to us all. Thanks especially to Araceli, Hassan, David, and Denise.

When I married Roger, I inherited a beautiful kinship with the Landeros Family. My thanks to in-laws, Rogelio Sr. and Fidela S. Landeros for their kindness and generous spirits. My marriage brought more wonderful siblings into my life with sisters-in-law Leticia and Elisa and brother-in-law Robert. Their life partners, Jaime, Jerry, and Cristina have added more blessings to our family. Between the two of us, Roger and I have seventeen nephews and nieces, one great niece, and of these young folks, we have baptized five and confirmed one. Luis, Lisa, Araceli, Albert, Alejandra, Isaac, Cheyenne, Emilio, Alex, Iván, Layla, Jaimito, Robbie, Lea, Germán, Cristián, Diego, and Aria, thank you for your smiles and laughter, for your hopes and dreams, and for being uniquely you.

I thank my grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, and friends for their caring support and best wishes, especially Bernita, Conchita, Miguel, Chela, José, Raymundo, Alicia, Elvira, Lourdes, Lupita, Maricela, Claudia, Elvia, Paty, Minerva, Hugo, Marissa, Laura Elvira, Hugo Eduardo, Alma, Bruno, Alonso, Jaime, Tony, Luis, Cindy, Caitlin, Lauren, Luke, Laura, Glen, Norman, Amanda, and my entire St. Augustine High School graduating class and high school teachers, Raquel Garza, Lupita Jiménez, Diana Garza, and Peter González. We recently celebrated a reunion. Go Knights!!

To my husband Roger and our daughter Isabella, I say, I love the two of you to the moon and back. Roger, eres mi media naranja. You are my soulmate, and I admire your strength of character, integrity, and kind-hearted nature. We met when we were teenagers and from the first day, my heart told me you were the one. All these years later, you’re still the one. Isabella, you are our biggest blessing, proof of God’s grace in our lives. When I was pregnant with you, I made plans to teach you so many things which I have, but in all candor, I believe I have learned as much from you as you’ve learned from me. And for all my mama bear instincts and habits, one big smile from you or a hug makes me feel so nurtured, supported, and loved that perhaps you’ve already mastered the mama bear way.

It is with great pleasure that I dedicate this book to the family of my birth and the family of my creation. Our bonds are deep and meaningful and our entwined lives have taught me the most important lesson of all. The answer is always LOVE.

NOTE ON USAGE

In its usage within the United States, the appellations “Mexican-origin” and “ethnic Mexican” refer to people of Mexican descent, whether they are nativeborn citizens, naturalized citizens, legal residents, or undocumented residents. The term “fronterizo” emphasizes the borderlands experience more than national identity. “Mexican immigrant” will be used when making references to those involved in the migratory experience from Mexico. These terms are used throughout the book.

In Part I, “méxico-tejano,” on rare occasion spelled “méxico-texano,” appears. Spanish language newspapers in Texas often used this term during the first couple of decades of the twentieth century to refer to the Mexican-origin community in Texas. “Mexico” in the appellation highlighted the Mexicanist identity and nationalism common in the community during this period. Transborder activists often referred to themselves and others they represented as “mexicanos” (Mexicans), regardless of citizenship status, as a form of ethnic kinship and political solidarity. Anglo-Texans did not make distinctions between US-born and Mexico-born people, often referring to all people of Mexican descent as “Mexican” or pejoratively as “Meskin.” Occasionally, the term “Tejano” is used in this book to refer to Texas-born Mexicans. In Part II, the appellation “Mexican American” appears, reflecting the emphasis on American nationalism starting in the 1920s but especially during the 1930s and 1940s. In a few instances, specifically in Chapter 6, where LULAC (League of United Latin American Citizens) is discussed, the term “Latin American” is used in the context in which activists used it such as to describe the Spanish- Speaking Parent Teacher Association, at times called the Latin American PTA.

Transborder activists used the term “la raza” (literal translation—the race) as a shorthand name for the Mexican-origin community. Early twentiethcentury political activists sought to foster ethnic pride and unity across the axes of gender, class, and national differences, and so the use of this appellation

conveyed Mexican cultural nationalism. In this vein, it resembles the term méxico-tejano, but la raza has a broader reach. It can be used and was sometimes used by transborder activists to describe all Spanish-speaking people or all people connected to the mestizaje experience that created Latin America and their collective struggles. The appellation la raza will appear occasionally in this study within the contexts in which these activists used it. Interestingly, in the 1930s and 1940s activists also used the term la raza from time to time to refer to Mexican-origin people, but for them it did not carry the same political currency. For Mexican American activists, la raza served more as a cultural identifier than a political one, whether they used it in reference to people of Mexican descent or to the larger family of Spanish-speaking people throughout the western hemisphere or the world.

The term “gente decente” that translates to “decent people” was commonly used among the middle and upper classes in Mexico as well as among middleclass Tejano communities to distinguish those deemed to be “respectable” because they lived in compliance with a set of bourgeois values from those who did not subscribe to this lifestyle or the ideological assumptions undergirding it. The term could carry both class and race undertones, but despite this, some within the lower classes adopted gente decente identities to the extent that they strove to climb the socioeconomic ladder or that they associated gente decente with notions of goodness and living an exemplary life.

“Anglo-American,” “Anglo-Texan,” “European American,” or “whites” is used throughout this study to refer to people socially constructed as white, both those who are Texas born and those migrating to the state later in life. When a reference is needed to denote migrants from Europe, the term “European immigrant” is used.

Redeeming La Raza

Introduction

Redeeming La Raza in the World of Two Flags

Entwined

Our society is comprised of women of Mexican-origin and birth. . . . It is dedicated to educational goals among the less fortunate sisters of our community who live in a state of real intellectual, moral and economic abandonment.

—Carolina Malpica de Munguía to the Governor of Querétaro, Querétaro, Mexico, March 26, 1939

In 1939, Carolina Malpica de Munguía wrote to the governor of Querétaro and other Mexican governors asking them to send representative handicrafts from their states to display at an art exhibition.1 She organized this event to promote Mexican culture among impoverished Mexican-origin Westside residents, especially the women, in San Antonio, Texas. Uplifting Mexican women formed the core of Malpica de Munguiá’s community activism. On June 12, 1938, “influenced by the social and cultural redemption labors so successfully sponsored by the Consulate General of Mexico,” she formed a female voluntary association to help lower-middle-class and working-class Mexican-origin women in San Antonio.2

Under the slogan “Todo Por la Patria y el Hogar” (“All for country and home”), Malpica de Munguía founded the Círculo Social Femenino, México (Female Social Circle, Mexico). Later renamed Círculo Cultural “Isabel, la Católica” (Cultural Circle, “Isabella, the Catholic”), this organization engaged in charitable projects, such as collecting donations for individuals and families in need; participated in cultural events such as the Fiestas Patrias (Mexican holiday celebrations); helped the Mexican consulate, the Mexican Library Association, and the Mexican clinic; procured legal aid services and medical services for people in need of these; organized English-language and sewing courses; and carried out myriad other activities that instilled a sense of Mexican cultural nationalism in Mexican-origin people as they navigated everyday life in American society.3

Ultimately, Círculo Cultural was a vehicle for female benevolence and for restoring the culture of la patria (Mexico) in the face of growing Americanization and the dilution of Mexican identity. It promoted a common ethnic identity to unify Mexicans across class lines as they struggled against racial discrimination and devastating poverty. But redemption was a political project that went further than American and Mexican nationalisms, for what Malpica de Munguía sought for Mexican-origin women and their families was their successful integration into modern life.

When this Mexican-born, educated, middle-class woman surveyed Westside San Antonio, she saw it in a state of economic and cultural decline. Her response was to bring together other women to operate the Círculo “to procure the moral and intellectual improvement of ‘women of modest means’ so as to benefit the community.”4 Women’s self-improvement, they believed, would translate into community betterment. In this way, the Círculo recognized women’s central role in confronting changes brought on by the forces of modernization.

Proud of her heritage, Malpica de Munguía retained her Mexican citizenship while working to advance Mexican cultural nationalism in her adopted country and helping Mexican-origin people adjust to life in the United States. She envisioned her role as creating social and cultural bridges between the two nations. She hoped to instill in Mexicans and Mexican Americans a sense of ethnic pride and unity and to demonstrate to Euro-Americans the value of a community that they increasingly denigrated as racially inferior. She intervened, subtly and not so subtly, using a discourse of domesticity that thinly veiled the gradual empowerment of women in the public sector as they challenged and changed the male-dominated political cultures of modern societies.5

The hybridized politics of Malpica de Munguía and other transborder activists emerged from a commitment to a struggle for rights within the racialized and conflicted bi-national spaces of modern Texas, the United States, and Mexico. Their activism needs to be understood as part of the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century processes of modernization in both countries, which were marked by national government support for economic development, increasingly strong civic political cultures, and a Victorian cultural ethos that over time blended into an increasingly modernist outlook among the developing middle class. Malpica de Munguía experienced this modern middle-class reality, but when she stepped into her role as community activist, she also dealt with the after-effects of economic modernization on a less privileged population.

The Westside men, women, and children mired in poverty who concerned Malpica de Munguía represented a mix of multi-generational Tejano and Mexican immigrant families employed in established and developing industries such as agribusiness, railroad work, light manufacturing, and an assortment of service jobs. Most of these jobs paid low wages and offered few prospects for

advancement. And yet, these and similar types of jobs animated the modern economic engines that saw a vast transformation of the American West from a conquered land with abundant resources to an industrializing region.6

Industrialization in the American Southwest, as in the Northeast, created the modern social environment defined by the development of markets, mass production, and commodification that increasingly took production out of the confines of the household. This story of economic development is a transborder one, connecting the US Southwest and Mexico, but the broad parameters are global. Invariably, becoming a modern society involves political, social, cultural, and economic changes connected to industrialization, urbanization, secularization, and bureaucratization. While modernization tends to be associated with Western Europe and the United States, in reality, it happened and continues to occur in diverse parts of the globe and at a varied pace.7 Critical to modernization are capital, resources (natural and technological), and labor power.

The United States, like any nation seeking development, has historically sought these major elements. An aggressive economic expansionism created the impetus for the ideological construct of Manifest Destiny even though democratic ideals served as inspiration and justification for the spread of American dominion across the continent. Ultimately, Manifest Destiny facilitated the quest for capital-generating enterprises, resources, and labor power because it allowed Americans to pursue self-interests and corporate interests in the name of cherished political principles. So great has been the lure of profits that the very health of democracy has been entwined with economic progress, for a nation of plenty can better safeguard the rights and privileges of its citizenry. But for all the magnificence and glory of American expansionism across the continent, the costs have been extraordinary. The weightiest burdens have been carried by those historically excluded from the American body politic, making redress all the more challenging. This has created a history of conflict often romanticized or mythologized, but nevertheless real and ever present, silently informing social roles and relations to the present day.

In south Texas that historical conflict came by way of the Texas Revolt (1835–36) and the US-Mexican War (1846–48) and created such an impact that by the first half of the twentieth century, people inhabited a US-Mexico border area shaped by an antagonistic relationship between neighboring nations and between Anglos and Mexicans. Mexican-origin borderlands people, fronterizos, experienced life as a conquered people long after the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo in 1848 had established their rights as citizens of the United States. For their part, Anglo-Americans in the region generally defined Mexicans, whether native or foreign born, as a problem, not a people worthy of rights.8

The labor power needs of a growing American regional economy in the newly acquired territories determined the role of Mexicans incorporated into

the United States. They picked crops for the agribusiness sector, laid tracks for railroads, worked mines for precious metals, and did many other dirty, potentially dangerous, and often low-paying jobs. Modernization forces in Texas and elsewhere thrust a majority of Mexicans into a proletariat class—the less fortunate sisters (and brothers) that Carolina Munguía found to be in a “state of real intellectual, moral and economic abandonment.”9 In the early years of this economic development project, a diverse workforce fed the labor needs of this massive engine of growth. Then, as immigration restrictions on Europeans and Asians created labor shortages, North American companies actively recruited Mexicans by offering them free rail transport and wage advances. But why were increasing numbers of people in Mexico accepting these jobs and migrating north?10

Mexico, too, became enmeshed in modernization during the last half of the nineteenth century. By the eve of the Mexican Revolution in 1910, foreign investors and Mexican elites owned much of Mexico, and their investment projects created serious socioeconomic dislocations. Liberal land laws, for example, encouraged development through privatization and the concentration of land in only a few hands. This destroyed communal land systems that had allowed peasants to maintain self-sufficiency. Thrown off the land, Mexico’s most vulnerable found themselves reduced to being day laborers. No longer in control of what they produced, these workers had but one commodity to offer: their inexpensive and much needed labor. Although many rural Mexicans migrated to their nation’s growing urban centers, the greatest magnet proved to be the United States, a country long accustomed to importing cheap labor.11

Mexican-origin people experienced the transborder dynamic as a paradox. The modern world emerging in the United States and Mexico disconnected them from agricultural traditions and thrust them on a foreign land that had once been theirs. The work of their hands contributed significantly to the transmutation of the land’s resources into wealth for an American society that despised them, seeing their presence as a burden and the two cultures as irreconcilable. Yet economic realities in both nations meant that Mexicans would continue to migrate north and many would settle permanently in the United States. There they moved into barrios, poverty-stricken ethnic enclaves largely untouched by the advancements of modern life.12

Like the inhabitants of other borderlands with competing nationalisms and cultures, fronterizos along the US-Mexico border had to address issues of identity and community within broader contexts of modernity and nation-building. In this process, a middle class consisting of Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans played a pivotal role, seeking to modernize la raza through transborder activism focused on the attainment of rights.13

This book focuses attention on those who questioned and disagreed with the dominant society’s designation of Mexicans as an inferior people. Transborder activists opposed race-based discrimination and sought to “save” la raza by challenging their marginality in the United States. The quest for rights itself represented a modernist intervention in a racist society. However, their efforts at redemption were not limited to societal transformations. They also invested much energy into effecting individual and communal changes among Mexicanorigin people. Activists such as Malpica de Munguía expressed faith in the tenets of modern society, believing that the best hope for the underprivileged lay in their adaptation to the best aspects of modernity. By lifting them out of their “state of intellectual, moral, and economic abandonment,” activists believed they could redeem la raza.

This study examines the paradoxical nature of the transborder human rights project that activists engaged in during the first half of the twentieth century. It looks at how these activists challenged modern social hierarchies that consigned them to second-class citizenship. And it asks what made their struggles for freedom modern. Using Malpica de Munguía as a starting point, it presents other cases of transborder activism that demonstrate how the politics of respectability and the politics of radicalism operated, often at odds but sometimes in complementary ways.

Redeeming La Raza examines the gendered and class-conscious political activism of Mexican-origin people in Texas from 1900 to 1950. In particular, it questions the inter-generational agency of Mexicans and Mexican Americans who subscribed to particular race-ethnic, class, and gender ideologies as they encountered barriers and obstacles in a society that often treated Mexicans as a nonwhite minority. How did these Mexican-origin activists respond to the severe poverty, discrimination, and violence they witnessed? How did the geographic and cultural borderlands informing their lives shape their responses? And how did concepts of race, ethnicity, class, gender, and nation influence the strategies they chose?

Middle-class transborder activists sought to redeem the Mexican masses from body politic exclusions in part by encouraging them to become identified with the United States. Redeeming la raza was as much about saving them from traditional modes of thought and practices that were perceived as hindrances to progress as it was about saving them from race and class-based forms of discrimination that were part and parcel of modernity. At the center of this link between modernity and discriminatory practices based on social constructions lay the economic imperative for the abundant and inexpensive labor power that the modernization process required. Labeling groups of people as inferior helped to rationalize their economic exploitation in a developing modern nation-state that

also professed to be a democratic society founded upon principles of political egalitarianism.

Thus, transborder activists worked within highly racialized environments and used a gendered class politics as they sought to deny white supremacists their excuses for depriving Mexican-origin people of their human and civil rights. Redeeming la raza was about discrediting the “Mexican problem” narrative or racial scripts that informed fear-based exclusionary movements whose prominent and loud voices included nativists calling for immigration restriction, eugenicists clamoring for racial purity, social scientists providing the intellectual justifications politicians needed to institutionalize racism, white supremacists building an extensive Jim Crow southern society, and working-class ethnics claiming whiteness and adopting racist attitudes toward groups in even more precarious positions than their own.14

Mexican activist communities used all the resources at their disposal to respond to external conditions and effect social change. Thus, this is also a story about more privileged Mexican-origin people encouraging less privileged raza to modernize and meet a standard of acceptable society. A strategy of gaining rights by attaining respectability undergirded the human and civil rights efforts of most of the transborder activists featured in this study. This approach presupposed that there was something inherently wrong with the aggrieved party and that in order to attain rights, they had to meet a certain cultural standard. What was supposed to be the Enlightenment’s highest ideal, “inalienable or natural rights,” became “conditional rights” based on the laws and/or customs of a particular government or cultural group—in this case the governments of the United States and Mexico and the modern middle classes and other elites of both nations, who collectively strove for their respective nation’s progress. However, in examining the Magonista movement and the labor activism of Emma Tenayuca, this book acknowledges the alternative vision of other activists who sought to redeem or save la raza, not through respectability but through a radical politics of transformation. In the case of the early twentieth-century Magonistas, change could only come through revolution. By the 1930s, Tenayuca’s quest for social justice relied on militant organizing designed to make the promises of New Deal liberalism meaningful for Mexican Americans.

Redeeming La Raza posits that there were significant continuities between the lives of many Mexican migrants to the United States and their descendants. Modernity, in the form of industrialization, urbanization, concentration of power, and the bureaucratization of society, touched many of their lives prior to their immigrating. Even when this was not the case, their migration was connected to transnational economic forces holding the United States and Mexico in an asymmetric relationship. Both were modern nation-states defined by a capitalist economic engine that bound the weaker nation to the dominant

one and by social stratifications organized around race, ethnicity, class, gender, and ultimately citizenship.15

In Mexico, however, class offered social mobility within the racial order, at least for some. Nineteenth-century Mexico had the distinction of having experienced Vicente Guerrero, a mulatto; Benito Juárez, an Indian; and Porfirio Díaz, a mestizo, as presidents. Many transborder activists, therefore, saw education and class mobility as mechanisms to combat racial discrimination. Class in both countries was related not only to an individual’s connection to the modes of production and consumption but also to understandings of gender, race, and respectability.

The modernist centerpiece of transborder activism was the concept of progress, which on the social level translated into self-improvement and community uplift. Privileged with educational opportunities that had allowed them to “overcome” racism, these activists taught other ethnic Mexicans, many of whom participated in working-class life and culture, to place their faith in the redemptive powers of personal transformation, which aligned with the ideal of the modern individualistic society. The success of middle-class Mexicans cast serious doubt on the idea that Mexicans were an inferior race, incapable of modernizing.16

The modern ideals and perspectives of the middle class did not appeal to everyone. Within the Mexican-origin community in Texas, the vast majority existed as a proletariat class, subjected to the worst socioeconomic byproducts of modernization. In time, educational attainment, military service, and access to higher-paying, postwar industrial jobs created opportunities for upward mobility. Thus, working-class people who aspired to a higher socioeconomic status could potentially achieve this goal for themselves or their children. For those who did, a middle-class status seemingly allowed them to divorce themselves from their humble roots. Thus, as the social and cultural worlds of the upwardly mobile changed, they developed an awareness of themselves as distinct from their working-class cousins who, in turn, nurtured their own class consciousness in reaction to a developing Tejano middle class as well as in response to their subordinate positionings within the worlds of work in a capitalist society. While racism most forcefully impinged upon the lives of the lower class, it occasionally affected the middle class. This meant that at least some middle-class Tejanos would remain politically united with their less fortunate brethren, if not always ideologically aligned.17

Once they secured employment as clerks, business owners, service providers, and in other “white collar” jobs, Tejanos expressed their modern outlook by becoming politically active to secure human and civil rights. Unlike their workingclass counterparts, who retained strong ethnic identifications and connections, the middle class more readily assimilated, in part because the move was a lateral