Dedication in Memoriam

Arthur Danto opened his book The Transfiguration of the Commonplace with an anecdote borrowed from Søren Kierkegaard. Commissioned to depict the biblical passage through the Red Sea, a painter covered a surface with red paint, explaining thereafter that the Israelites had already crossed over and that the Egyptians were drowned. Danto used the anecdote to devise a thought experiment, a lineup of red squares, from which then he produced an analytical philosophy of art. He asked how we come to know what art essentially is when nothing other than red square surfaces are all we are given to see. Sitting with Arthur many years ago, I naively remarked on the seemingly few representations of the Red Sea Passage in the history of painting. How odd, he quipped back, if all a painter needs is a large bucket of red paint. In this moment, a deep smile stretched the lifelines of his face because, of all thoughts, this one he believed the least. What more art needs beyond its basic materials gave Danto his philosophical project for fifty years. It led him to an emancipation narrative for the artworld, to declare art’s end with a call to freedom aimed at exposing a politics of exclusion in the world as a whole. It is the narrative of liberation, beginning at the Red Sea, that inspires my own book.

New York, 2021

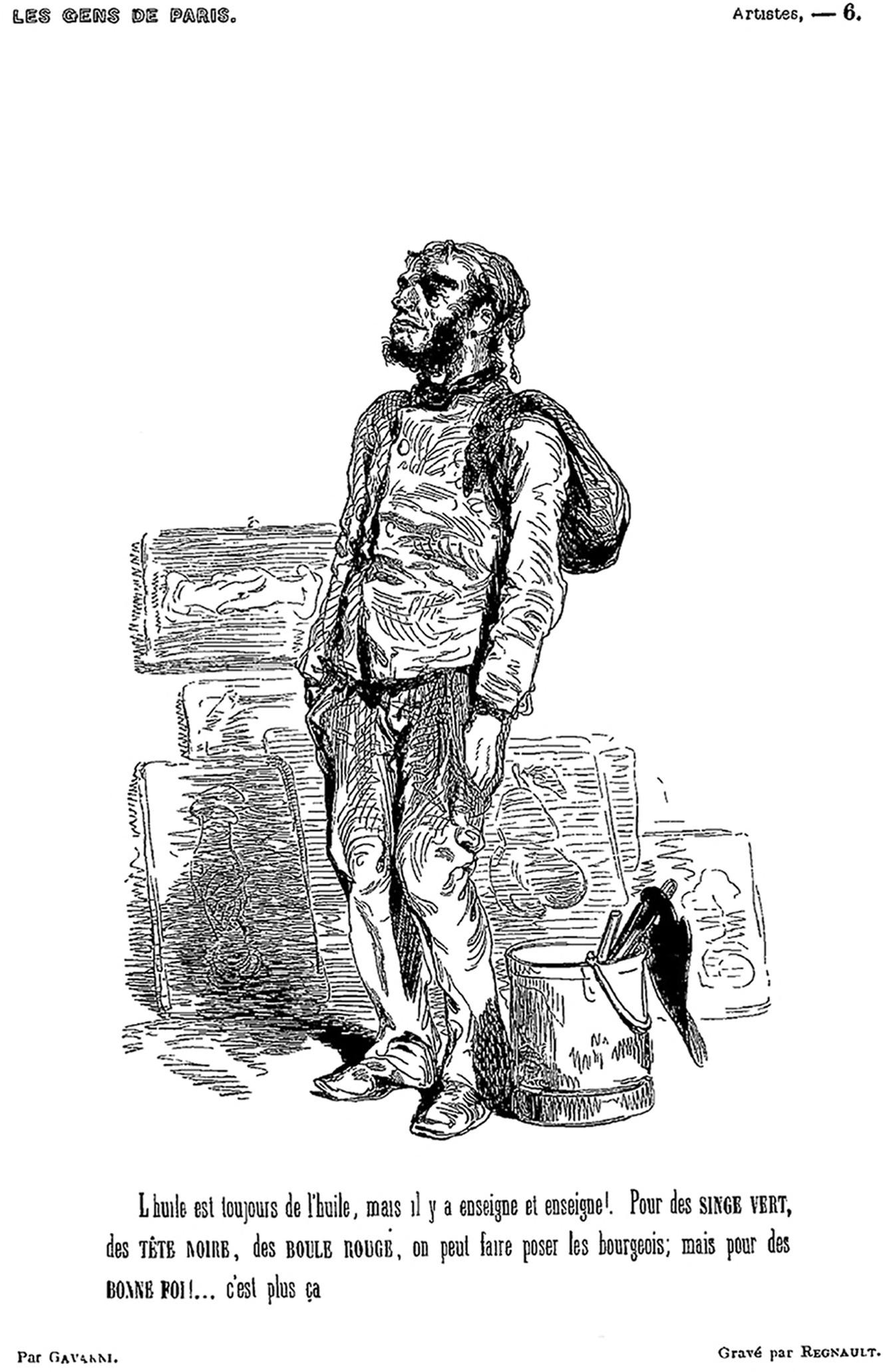

Figure 0.1 Paul Gavarni, “Oil is always oil, but there is a sign and there a sign/lesson! For Green Monkeys, Black Heads, Red Balls, we can ask the bourgeois, but for those of good will, there’s something more.” Le Diable à Paris: Paris et les Parisiens (Paris, 1846). Courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF-Gallica).

Accounts to reconcile:

Anecdotes to pick up:

Inscriptions to make out:

Stories to weave in:

Traditions to sift:

Personages to call upon:

Panegyricks to paste up at this door; . . .

To sum up all; there are archives at every stage to be look’d into, and rolls, records, documents, and endless genealogies. . . . In short there is no end of it.

Laurence Sterne, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman

Something is uncanny—that’s how it begins. Ernst Bloch, “A Philosophical View of the Detective Novel”

If the tireless pursuit of justice is your day job, it helps to spend time at the Café Momus in “La Bohème” at night. Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Contents

Preface xv

Borrowing an Anecdote * Flouting Expectations * Seeking Wit * Passage to Port * Marseille to Manhattan * Freezing the Frame * Sketch and Shudder * Drawing Out the Anecdote * Diversionary Method * Piracy and Luck * Rogue Wit * All Is Nothing * Exemplary Anecdote * Division and Discernment * Naming Predecessors * Predecessor Studies * Exodus Concept * Bloodlines * Refiguring Modernity * Stepping on Toes * Critique and Complaint * How to Read for the Red Thread

PART I

1. Thought Experiment 3

The Brief * Disengaging the Mind * Uncommon Reader * First Lines * First Sight * Shadowplay on Nothing * First Strike * Draining Art’s Concept * Shakespearean Overtones * Shattering Expectation * Exacting Images * Warehouse Test * No Decision * Less Is More * Red and Square * Cataloguing the Commonplace * Enraged Painter * Before and After the Law * Smiling at the End of Art

2. Emancipation Narrative 27

Same and Different * Caves of Discrimination * Exclusion in World-History * Beyond the Pale * Last Master Narrative * Reviewing the End of Art * Last Strike * Headlines of History * Extending Monism * Living with Pluralism * Plying Paint * Mind the Gap * Egalitarian Attitude * Abusing Beauty * Choice without Commandment * Choice beyond Capital * Slogans of Freedom * Ending in Good Humor

3. From Sea to Square to Sea 55

Hitch and Hike * Self-Evidence * Attuning the Eye * Stubborn Pigeon * Sober Citizen * Re-Visioning the Anecdote * Anecdote in the Air * East/West * Mosaic Mimesis * Unnatural Wonders * Getting It * Impossible Masterpiece * Madonna of the Present * Painting Is Dead * Two New Men * Beginning Again

4. Passages of Bohème

Preface * Scenes/Book/Play * Making and Unmaking a Class * City of Dreams * Adaptation * Reception and Conflict * Paradox * Dogma * Poverty and Mobility * La Tromperie * Failing to Finish * Musketeers/ Marketeers * Wither and Waste * Bohemia Undelivered * War and Doubt * Graves of Revenge * Delimiting the Concept * Acid Wit/ Counterfeit Coin * Trapped Poet * Who Would Be King * Water/Color/ Cloth * Avenging Painter * Trafficking Ideals * Watershed * Misery and Poverty * Eyes and Ears

83

5. Testament and Table 128

Prelude * Stages on Life’s Way * Strategic Disfigurement * Diapsalmata * Knocking on Wood * Fragmenting a Life * Penny for a Thought * Poet’s Cry * Age of Youth * Philosophical Fire * Pockets of Idle Thoughts * Philosophical Furniture * Desks of Detection * Bearing Witness * Mood of an Aesthete * All That Nothing Is * Expectation/Explanation * Standing Apart * Leveling Conceits * Retrieving Waste * Saving Scraps * Postlude

6. Contesting Opera 160

Paragone/Ekphrasis * First Images * Bird Brain and Black Magic * Turks and Zouaves * Queste Marine * Competitive Words * Staging the Red Sea * Speedy Delivery by Foot and Mouth * Refiguring a Prophet * Artist of the Future * Sacred Cloth/Secular Criticism * Shadowing Wagner * Reproductive Justice * Blues Musician * Moment of Menace * In and Out of Time

7. Sea Scenes 181

Staking a Claim * Competitive Operas * Questa Roma * Questo Mar * Egotism and Lament * Breaking Barriers * Questa Mimi * Dying of Beauty * Trembling Strings * Lost Illusions * M for Murder * Figure in Grey * Reviewing the Opera * Opera in the Background * Crossed Paths * Red Sea/Red Ideal * Stitching a Worn Cloth

8. Between Fact and Fiction 209

What Could Have Been * The Real Marcels * Refiguring a Passage * Killing Offspring * Put Down Six * No Contest * Sausages * Exemplary Lives * In a Hurry * Picking on the Spanish * Torture for Art’s Sake * Pharamond * Fooling the Cognoscenti * Painter up a Sleeve * Costumed Ball * Looking Out for Parasites

9. Refiguring Exodus

Typology * Event * Naming * Biblical Brothers * Overwhelming Power * Leaving the Enemy Behind * Revealed Remainder * So Hard a Task * Preparation and Promise * Horns and Rays * Second Figure/ Second City * Absenting Moses * Chosen Lines * Visible Prototypes * Grave Hand/Grave Song * Broken Tablets * Reverting to Type * Perpetuating Types * Trading Descriptions * International Exodus and Red Bohème * Making Lists * Rites of Passage

10. Bohemia-Bohemian-Bohème

On Foot * Winter’s Tale * Four Winds * Winter’s Night, a Traveler * Meeting on the Path * Unfitting Shoes * Changing Landscape * Also by Name, Egyptians * Down and Out in Paris and London * Grub Street * Wasting a Toast * Elective Eccentricities * Recoloring La Bohémienne * Bohemian Philosophers * Trading Tales * Education and Inheritance * Winter’s Return

11. Egyptian-Jewish Bohème

Dispelling a Thesis * Expulsion * Egyptians, We Call Them * Diminishing Description * Names * Gypsy-Egyptians in Britain * Rewriting the Origin * Epidemic of Errors * Plague to Port * Race of Science * Disguise * Persecution and Rescue * Religion by Reason Alone * Leaving Everything and Nothing Behind

235

268

293

12. Mastering the Cant in Cafés of Complaint 312

Artspeak * Household Words * Talk about Town * Banter * Red Cant/ Red Jews * Beggar-Industry * Writing on the Wall * Gone with the Wind * Hanging from a Tree * Masters of Cause * Pharaoh in London Town * Gain in Translation * Patronizing Wit * Expulsion/Exile * Momus/Midas/Moses * Buffoons by Paper and Toast * To Whom the Red Sea Appeared * Fishing in the Red Sea * Portraiture by Pen and Brush

PART IV

13. Reds of Art and War

Everywhere Red * Wine-Dark Sea * Sinking and Spreading in Red * Red for Exit * Red Sea of Claret * Little Red Man * Red Sea Song and Seal * Sinking Red Sun * Championing Red * Vanishing Civilizations * Red Wall/Red Death * Sewer Songs

339

14. Grey Days for a Gay Science 357

Mothering Invention * Gay Science as Critique * Immortalizing Life * Sustaining Loss and Life * Egotism and Irony * Spoils of Earth and Ground * Dismal Science * Heavy and Light Steps * Sun Rise * Homelessness * On Land/At Sea * Wasting a Song * Abusing Art * Vain Rewards * Birds of Passage * Birds of a Feather * Onto the Ladder * Ladder with Bracket * Ladder Going Nowhere * Descending Scale

15. Proverbs on the Path to the Absolute 392

Black/White * Proverbs * Deaf Ears/Fat Cats * Sweet Elbow/Sour Grapes * Public Secret * Downcast Eyes * Mastering Contraries * The Wit of Mind * A Saying for Everyone * Absolute Cows * When the Owl Takes Flight * Reviewing Hegel * Revolving Wit and Revolution * Philosophic Animals * Domesticating a Proverb * Raining Cats and Dogs * Philosophy of Proverbs * Updating Cats and Cows

16. Thought Experiments in Color 425

Seriously Mocking Monochromes * Shades of Grey * Originating Red * Experiments and Maxims * Trusting Instruments * Authorizing Epigraphs * Monochrome/Monochord * Marginalia * Incoherent Monochromes * Pitch in Black and Red * Dangerous Waters * Paint It Black * Waiting Game * Wit in Grey and Red

17. Red Thread 456

Why Red/Why Thread * True to the Letter * Curious Work * Twinned Legacies * Threads for the Pen * Golden Threads and Red-Sea Ropes * Thread without Red * Thread Inner and Outer * Borrowed Threads * Piracy and Shipwreck * Knotty Problems of Identity * Jarred Rope * Rogues-Yarn and Flag-Ships * Trials by Fire and Hot Air * Hanging by a Thread * Stealing Away with the Literal * Lost and Found * Endgame

PART V

18. Painter of Moods, Poverties, and Professions 485

Absent Image * Musician Inside and Out * Who’s Who * All the World a Stage * Sound Drowning * Lydian Measure * Irregular Dance * Prostituted Professions * Touch and Turn * Deafening Silence * Distressed Poet * Mood and Mind Changes * Scene and Sea Changes * Falling Fortunes * Falling Pictures * Speculating about a Painting * Coda: Enraged Critic

19. Street Signs of Libation and Liberation 514

Warning Signs * Unsober Paths to Sobriety* First Histories * The End of Signs * First Signs of Abuse * Name-Dropping Signs * Ludic Origins * Flattening Signs * Amplifying Complaints * Times Squared * Worn Visions * Vaudeville to Opera * Rain Check/Watering Signs * Delivering Pharaoh’s Beer * Red Sea of Beer and Gin * Found Children * Found Art * Quill and Brush

20. Spreading the Anecdote 546

By Order of the Day * Seeking a Red Wall * In-House Evidence * London Luck * Deleting the Anecdote * Millerism * Three Suspects * Chasing a Tale * Making Headway * Quick Return * Theme and Variation * Tone-Painting in the Red Sea * Hermeneutics * Master Painter * Barefooted Truth * Master of Letters * Checkered Wall * Master Poet * Mirror, Mirror * Not-So-Simple Simon * Fishing in Yiddish * Cheese and Arms * Danes by the Red Sea * Stopping in Copenhagen * Back to the Beginning

21. Tying the Knot 579

Love’s Labor Lost * Laboring in Vain * Brush and Sweep * Being Smart * Midwife Delivered * Red Thread Rewound * Old Wives Tale * Brothers-in-Arms * Measure for Measure * Foot under Foote * Wit’s Gravity * Contracting Marriage * Corners/Comets/Squares * Huge Heaps of Littleness * Sinking Blood Sport * Breaking the Bond * Back to Square One

Preface

The art of preface-writing is, perhaps, the art of concealing the anxiety of an author.

Isaac Disraeli, A Dissertation on Anecdotes

Borrowing an Anecdote. Arthur Danto opened The Transfiguration of the Commonplace of 1981 with a thought experiment gesturing toward the Exodus. He contained the gesture in a red square painting as imagined by Søren Kierkegaard:

Let us consider a painting once described by the Danish wit, Søren Kierkegaard. It was a painting of the Israelites crossing the Red Sea. Looking at it, one would have seen something very different from what a painting with that subject would have led one to expect. . . . Here, instead, was a square of red paint, the artist explaining that “The Israelites had already crossed over, and the Egyptians were drowned.”

Reading these lines, we need not follow Danto’s instruction to consider a painting specified as a square of red paint. We may ask instead: wherein lay the wit of the Dane? Danto found the wit in Kierkegaard’s being able in the 1840s to imagine a monochrome painting decades before painters could acceptably produce such an artwork for the museum. Is this, however, the only or even the right way to read the wit? It is wise to ask what Kierkegaard wrote himself, although immediately we have a choice: to read the relevant passage in Danish or in translation. From 1843, we read:

Mit Livs-Resultat bliver slet Intet, en Stemning, en enkelt Farve. Mit Resultat faaer en Lighed med hiin Kunstners Maleri, der skulde male Jødernes Overgang over det røde Hav, og til den Ende malede hele Væggen rød, idet han forklarede, at Jøderne vare gaaede over, Ægypterne vare druknede

Danto read the 1940s Svenson-Svenson translation of Kierkegaard’s Either/Or:

The result of my life is simply nothing, a mood, a single color. My result is like the painting of the artist who was to paint a picture of the Israelites crossing the Red Sea. To this end, he painted the whole wall red, explaining that the Israelites had already crossed over, and that the Egyptians were drowned.

The words differ from the 1987 Hong-Hong translation that is mostly used today:

My life achievement amounts to nothing at all, a mood, a single color. My achievement resembles the painting by that artist who was supposed to paint the Israelites’ crossing of the Red Sea and to that end painted the entire wall red and explained that the Israelites had walked across and that the Egyptians were drowned.

In Part II of the present work, when situating this passage within Kierkegaard’s life and thought, I attend to his deliberate choice of words. Here, to begin, I note only the potential differences of meaning suggested alone by the translations. For there is a difference in writing of a life result instead of a life achievement because obviously not all results are achievements; or of a life as simply being nothing in contrast to its amounting to nothing; or in writing generically of any artist as opposed to the more specific-sounding that artist; or in declaring the Israelites to have already crossed over contrary to their having walked—since walking could capture either their trepidation when entering the waters or their security in knowing that they were being safely guided to the other side.

Danto borrowed the Red Sea anecdote from Kierkegaard. Kierkegaard borrowed it also. Borrowing, like walking, works as a leitmotif that is inextricable from a life-motif—which is to say from age-old obsessions with origin, ancestry, and legitimate birthright, or from deep desires and anxieties to belong perhaps as a self-selected or chosen people. Borrowing, adaptation, and appropriation carry an urgency of desires and demands for recognition and admission, laden with a social and theological luggage of crossing and arriving at new lands of great promise. Tracking these motifs, I explore the many treatises and artworks that have addressed liberty and wit while also exposing a sometimes quite horrifying history of persecution and exclusion of peoples: the Israelites, Hebrews, or Jews, and the Egyptians who, with all the mobility of gypsy names, came to be branded as undesirable foreigners or immigrants, and most particularly as bohemians arriving in France from the lands of Bohemia.

Flouting Expectations. Introducing Kierkegaard, Danto noted the Dane’s wit as though evident in the description of the imagined painting. But it wasn’t as evident as all that. Did the wit lie with the artist’s deed and specifically

with his having flouted an expectation? (We may suppose that the artist was a he.) Kierkegaard wrote of that artist who was supposed to paint the Red Sea Passage. Danto told of spectators expecting to see something different from what the painter gave them to see. Kierkegaard’s formulation makes one wonder for whom the artist was painting and what the expectation was— which, not being met, required the painter to explain his deed. The only other person Kierkegaard mentioned was someone (the writer of the sentence) assessing his life result by analogy to the painter’s deed. Still, it wasn’t this writer whose expectation was flouted. There seems to have been a silent figure, calling for a philosophical detective to discover his identity (assuming that he too was a he).

My enquiry spins around the incongruous logic of expectations and explanations. Readers are requested to be patient. For, beginning already with this preface, I offer thoughts and images without preparation, allowing their explanations to unfold in due course. Inspiring my beginning is the first line of Hegel’s preface to his Phenomenology of Spirit. Beginning with the word explanation (Erklärung), Hegel unraveled a lengthy first sentence to challenge readers’ expectations regarding the philosophical passage toward knowledge or enlightenment (Aufklärung). Where freedom is the issue, as it was for Hegel, Kierkegaard, and Danto, first words, lines, and images matter in preparing for middles and ends—in philosophical arguments as much as in artworks.

To tackle the incongruity and inversions of wit in the history of a single anecdote is to understand contrary connotations of secrecy and exposure, of concealing and revealing. The etymology tells that an anecdote contains a secret, as something edited or curtailed, as well as a piece of proverbial wisdom. The secrecy carries a sense of what is arcane, long known, but also suspect when uses turn to abuses. Anecdotes, like epigrams, fables, riddles, aphorisms, parables, and proverbs, have always been told simultaneously to give out one meaning while withholding another. They give something to plain sight and something different to insight, and the wit lies in the movement between the two.

Throughout, I show philosophers, writers, and artists twisting and turning a proverbial wisdom about artworks and human lives to render the familiar unfamiliar, the common uncommon—or the other way around, with all the wit of the vice versa or quid pro quo. Many have explored wit under various rubrics including the comic, humorous, ludicrous, incongruous, parodic, satirical, and laughable. Liberty has likewise been explored alongside freedom, emancipation, deliverance, autonomy, self-determination—and their contraries. I use all these terms in situ: to preserve the tension between expectation and explanation, especially where this tension keeps philosophy on its toes.

Seeking Wit. Let us now run up a veritable mountain with the most mole-like of questions on our back to ask whether there was a specific artist, a painter by profession, responsible for the anecdote’s being told as it was. Or was the painter only an everyman artist invoked to exemplify an intent not to produce art in expected ways? How would it feel if, as a viewer, one expected to see the Red Sea Passage painted one way only to be asked to view it as an entirely red surface? Would one feel theologically relieved, offended, artistically clarified, or only conceptually confused?

Danto made the painter produce some sort of a canvas for a museum. Kierkegaard let the red paint cover a wall—a wall as significant perhaps as a wall of water securing the Israelites a safe passage. Walls have always carried a force for artists engaged with interior decorating in commercial or urban projects, or with the decoration of ancient tombs or early frescoes. From the highest institutions of church and government to the common streets, and often into city sewers, it has mattered how walls are painted and which bit: the ceiling, corner, or along the skirting, and especially, again, when the painted scene has involved a thickly invested body of water. Architectural metaphors are everywhere in my book, as are contrasts of land and sea; water, mud, and air; solidity and liquidity. It has always also mattered how much artists have been paid, if paid at all, for painting walls, and whether the project has made a difference to their lives. Indeed, a Red Sea painting on a wall could define a painter’s entire attitude toward his life, as Kierkegaard began with a writer saying something, albeit strikingly little, about his life result. But why cover the wall with red paint? It helps to acknowledge the incongruity in a wit that comes with the potential confusion of competing descriptions. There is nothing strange in describing a painter using a single color to produce a monochromatic painting. The situation becomes unwieldy only when one speaks of the artist producing a painting merely by covering a wall with red paint. This is because the use of the merely suggests that the painter has played some sort of trick—literally, the trick of a cover-up. Yet, to what end?

Then again, maybe the wit lies less in what was put on the wall than in the painter’s explanation. For doesn’t the line that the Israelites have already crossed and the Egyptians drowned sound in rhythm like a punchline to a joke? And doesn’t this make one wonder how else the painter could explain the action and whether another explanation would satisfy? What if no explanation was accepted? Would the painter be punished and, if so, by whom and with what authority? Might he even be flayed, as early artists of ancient myths were punished, or dismissed from a certain task or employment, or simply banished from town?

One thing is clear: if the wit lay in the explanation, it was inextricable from the sense of flouting an expectation. When an expectation is flouted, an explanation is usually demanded. Had the painting of the Red Sea met the viewer’s eyes in

accord with the expectation, nothing further would have followed, and a book like this would not be needed to liberate its wit.

Passage to Port. Notice now something almost never noticed. One of the most often-produced operas in the world begins with a reference to a Red Sea painting that turns out contrary to expectation. Questo Mar Rosso are the first words sung in Puccini’s opera La bohème of 1896, libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica. Questo Mar Rosso—This Red Sea, it drains and freezes me as if raining upon me in drops. Composed in four painted scenes (quattro quadri), the opera opens without overture to suggest the content of a painting and by inference its title Il passaggio del Mar Rosso. When the impoverished painter Marcello introduces his painting, it is still being produced. Trying to paint while interrupted by the cold, he determines to drown a pharaoh in revenge (Per vendicarmi, affogo un Faraon). By the time the story is over, his painting has become a commercial signboard for a tavern at the Barrière d’Enfer with a new content and title: At the Port of Marseille (Al Porto di Marsiglia).

How the Red Sea painting ends up in an unexpected port will obviously be one story to tell. First, however, the motivating idea. Puccini’s opera opens with a painting that starts out as one thing and ends as another. Its subject matter changes and its status too: from being a potential artwork for the museum to being a commercial signboard for the street. This movement, suggestive of a larger one between art and its commodification, originated not with Puccini or his librettists but with the writer of the opera’s primary literary source: Henri Murger in his 1840s Scènes de la vie de bohème. What Murger did with the painting divulges what the scenes are about: bohemian life considered itself as a passage.

But if a passage, the life had both to begin and to end. Murger split the life’s passage along a high road and a low road for the youth described as les enfants de bohème. Walking the high road with a carefree gaiety, they carried ideals of beauty, love, and freedom in their pockets. Gazing high, they thought only of how masterpieces could be produced for the sake alone of art: l’art pour l’art. Along the low road, they walked impoverished, preoccupied by quotidian demands, by what in the day were uncomfortably couched as the dismal demands of economics. Going low, they became evermore bitter toward those whom they blamed for their not having yet produced their masterpieces and consequently for their not having received the recognition they believed they deserved. Murger designed his scenes to split the road but to reveal the split as false. Living on ideals alone (la vie de bohème) too often resulted in dying from the lower life (la vie quotidienne). Along the passage, the high road, when lived too high, displayed a wit of superiority, and the low road, when lived too low, a wit of contempt. Could, then, the life of bohème be lived rightly at all?

Murger’s scenes have been well read as sentimental and idealistic, as espousing a gentle as opposed to an aggressive liberty. Still, there was a deep disenchantment, of which the consequence was to regard la vie de bohème as a necessary stage on life’s way (the stage of youth) while also as a non-starter. The sentimentality and idealism tending toward a pure life of dreams were already reflective modernist markers of a life promoted on desperately contradictory terms. I read Murger’s scenes to mirror what Hegel, Kierkegaard, Marx, and countless others perceived in the same period as the threateningly hollowed-out and ironic attitude of the aesthete within the aesthetic stage on life’s way, and what, before Nietzsche, many described as the grey or dismal antithesis to the gay or joyous science. The argument was against neither joy nor pleasure but against an increasingly pathological cruelty and impotent revenge, sustained by a misguided, capricious, or false wit. Before fully drawing out the terms of the wit in Part V, I show in the Parisian schema and in Puccini’s opera that the result of la vie de bohème was a death characterizing the lifestyle as much as the art. As a selfconscious concept for a modern project of liberation for both the artworks and the artists’ lives, la bohème was a fractured concept, full of paradoxes already at the beginning of its modern promotion shortly after 1800 and not just at the end—whenever and however many times the end was claimed.

It will help to approach the life of bohème as an antagonistic part of the life of the modern bourgeoisie to explain why, within Murger’s scenes and Puccini’s opera, few artists survived as artists and no masterpieces were produced. Yet, to claim that from within bohemian life masterpieces were somehow impossible, unrealizable, or, with Balzac’s term, inconnu, is not to exclude the result that a bourgeois work for a bourgeois public could be produced about bohème. Puccini’s opera is not a bohemian opera; it is a bourgeois masterpiece about bohème. One cannot underscore this enough, although it leaves the conceptualization of la vie de bohème as fraught for us still today as at its start.

Marseille to Manhattan. Marcel’s would-be painting of the Red Sea Passage appears several times in Murger’s scenes, with different results. The painting is supposed to be the grand tableau of his life. The most pertinent scene tells of how, over several years, Marcel submits his painting to a jury for annual exhibition at the Louvre. While each time submitted with a new content and title, the judges see only traces of its original incarnation as Le passage de la mer Rouge. The story ends not with the jury’s refusal to hang the painting but with the unexpected trick of a Jewish trade, when a nameless sign-painter turns Marcel’s painting into a commercial signboard with a content suited to its new title: Au port de Marseille. Murger wrote his scenes in the late 1840s but set them in the watershed year of 1830 in the turmoil of a France split between the revolution of the general or common will and the restoration of monarchy. He dramatized a thesis of the

demise or death of art, described further as an epidemic of the age. If the greyhaired jurists couldn’t see past old masterpieces to what was youthful and new, what better than for the artists, starved in spirit and body, to withdraw to salons of constant refusal, resentment, and revenge—unless, that is, they found ways to celebrate being revolutionary artists for the streets. Condemning the revolutionary picture, Murger let his figures of bohème dance around it with all the intoxicated laughter of the gai savoir. Making them dance because in youth they had to dance, he then condemned the illusions of their life as resulting in nothing. Drawing on his troubled times, Murger gave Marcel a temporal lineup of paintings that, presented as discernible, are judged as deceitful versions of the same work. Here, discernibility means seeing one painting as persistently, though dimly, present in another. Claimed differences of content or style prove insufficient in the discerning eyes of the jury. To counter the jury’s alleged misjudgment, Marcel determines revengefully to throw as much red paint onto the canvas as he possibly can.

This story serves as an extraordinarily illuminating forerunner of Danto’s thought experiment.

Danto invited readers to imagine several images lined up in a row. All are distinct artworks, except one, a commonplace board. Whatever makes the images distinct images of art and whatever separates the artworks from the commonplace board, no differences are made to matter regarding how they are seen. All are to be indiscernible, perceptually indistinguishable, to have exactly the same appearance as flat red squares. To so see them is to come to understand that what makes art art cannot depend alone on appearance, or at all on what is given to the merely seeing eye. (Put this way, who would think the reverse?) Danto explained the more or difference of art from commonplace things by writing of artworks as embodying meanings following from an artistic engagement of the human mind within a lifeworld that in 1964 he named the artworld. He was encouraged to his conclusion by the frenzied confusion he observed in the artworld of his day, when artworks were being made to look just like commonplace things and often just like the most commodified of wares. He was inspired to a spatial lineup of indiscernible red images to show that an artwork is an artwork regardless of any institutional decrees derived from misguided presumptions about how artworks should look. Onward from the 1960s, he produced an emancipatory thesis out of the spirit of Hegel, eventually sloganized as the end of art. The end marked the end of art’s disenfranchisement due to a history of significant philosophical errors regarding art’s definition. Regardless of any particular appearance, all art should be, because by definition it now could be, admitted into the artworld in freedom without exclusion. With extreme political conviction, he sought a definition for an artworld conceived as a pluralized commonwealth for all and everything that is art. Turning the tables on the France and Germany of the earlier

revolutionary period, he claimed the advantage of his own American, and of his own philosophical, times.

Freezing the Frame. In Puccini’s opera, when Marcello’s painting is introduced, it immediately becomes a candidate for being thrown into the stove to produce a warm flame. Little more is heard or seen of the painting beyond a scenedescription to open the third act. The description specifies that the painting has become a signboard for a tavern with a new title—but instead underneath (ma sotto invece) is painted in big letters Al Porto di Marsiglia. The but for the title-change is not explained. It prompts only a further description of the sign as accompanied by two painted figures on the door: a Turk and then a Zouave sporting an enormous laurel crown over his fez. But what have a Turk and Zouave to do with la bohème? And what has la bohème to do with a painting that, beginning its passage at the Red Sea, ends up ported in Marseille? Might the Turk and Zouave stand for the poet and the painter? What have these figures to do then with the passage and the port?

Does Marcello’s destructive impulse toward a pharaoh at the opera’s start bear on the death of the woman named Mimi at its end? Is Mimi figured as model and muse somehow a martyr to Marcello’s cause? Does her death relate to what Marcello’s lover means when she viciously demotes him to a pittore da bottega, to a workaday painter who survives by repetitively painting grenadiers on a façade (guerrieri sulla facciata)? The opera’s third act is a freezing tableau, a greying-white monochrome for a cold wintry day. It places Mimi so that she can listen unseen to a conversation in which the poet Rodolfo tells Marcello that his relationship with Mimi has fallen apart not because he is jealous of her flirtations with rich men, but because he knows she cannot survive his poverty. Likening her to a faded flower that needs warmth, he knows love alone is not enough. This moment of truth (O mia vita! È finita) occurs at the Barrière d’Enfer under the signboard that shows (in the opera) the final port of Marcello’s painting. Why this site and why a place suggestive of a tollgate of no return?

Over the last several years, I’ve asked many how Puccini’s opera begins. Almost no one can answer, though they know how it ends. Even if some recall a painter standing before his easel, they almost never remember the painting’s subject matter. Is this because the Red Sea Passage is rarely addressed as a significant theme in academic or popular discussions of the opera and its productions? Or because the opera deliberately drowns out the subject matter with the orchestral sea of tears that flows through the love story? Or because the last scene is just what audiences prefer? Or because we tend to remember only how passages end and not how they begin? These reasons all carry weight. My

reasoning is otherwise aimed: to read the opera’s end given a beginning that matches other artworks that have set out to liberate a people: their lives, their thinking, and their arts. Setting out to liberate means making a promise, sadly, without the guarantee of delivery.

Sketch and Shudder . Part I presents Danto’s emancipation thesis for the artworld and by extension for the whole world: a world including persons arriving at ports of entry hoping to be admitted. Had he described a Red Sea painting of his own making, it might have been a monochrome red square produced for the most modern museum of art titled Au port de Manhattan Part I covers his Red Squares thought experiment, his end of art thesis contextualized by his philosophy of history, and his engagement with others who used the Red Sea anecdote, including writers of la vie de bohème. The book thereafter investigates what it has long meant to picture freedom with a wit that attends the mind’s constant experimentation with its thoughts, moods, and perspectives. It tracks the exclusionary theses of emancipation to which Danto responded oftentimes with rage. Rage is another of my running motifs. Danto designed his thought experiment as a radical antidote to an aesthetic and social vision that was supposed to liberate all but only liberated some or, at worst, only a chosen one . Proclaiming the end of a vision of freedom abused, Danto attempted to safeguard art’s freedom analytically, in an all-inclusive definition of art. That his safeguard proved too safe detracts little from my appreciation of the political urgency with which he approached his project.

Part II presents Murger’s deflation of Marcel’s would-be masterpiece to a signboard titled Au port de Marseille and Kierkegaard’s Red Sea passage as situated within his life’s work. (An uncapitalized Red Sea passage refers to a piece of text, unlike the capitalized reference to the biblical Passage.) The discussion then turns to situate Puccini’s opera against the backdrop of earlier musical, visual, and literary arts that have drawn on the Red Sea Passage and oftentimes to expose the tensions in la vie de bohème. (Mostly, I refer to writers or artists of la vie de bohème rather than to bohemians.) Part II finally returns to Murger’s story of the painting to seek art-historical and literary sources for the painter Marcel, to prove Murger’s borrowings from a range of particularly Parisian tellings of the Red Sea anecdote.

With three more parts, the book explores the many more lineups and repetitive strings of names, titles, and images associated with the Red Sea Passage: its anecdote, its painting, its song, and its role as political allegory. Working with a repetitive string theory, we can still feel a deep shudder given our own troubled time of migrating peoples. Our times are as past times: times overly driven by prejudice, persecution, and put-down.

Drawing Out the Anecdote. Countless thinkers and artists have employed a language, biblical and ancient in origin, that places the poetry and wit of wordplay, metaphor, and punning on a path of significance for our understanding of art’s complex capabilities. Equally many have engaged a dialectic pitting reality against appearance, truth against error, and individuals against their worlds. Before Danto prioritized the matter of indiscernibility as the best route to knowing the truth about art, others played with examples that used two or more terms, statements, or images with different identities or meanings to produce confusions when any such pair sounded or looked the same. Recall how many comedies and tragedies of life and death have been spun from doppelgänger errors of identification, from witting and unwitting disguises, from puns and mispronunciations of names, or from social and gendered confusions of clothing and appearance. From as much these kinds of confusions as from the principles formally articulated within philosophical theories of identity, I show how the issue of discernibility and indiscernibility has inextricably been bound to that of inclusion and exclusion.

Danto found error in appealing to the discerning eye when the discernment restricted the full potential and freedom of how art can look. Before this, many asked after the meaning of cultivating a discerning eye and mind capable of seeing differences that were meant to count for something as opposed to differences that were not meant to count. They investigated, like theorists today, the theory-based perspectives or the implicit biases that lead us to see the same thing in different ways, and sometimes in diametrically opposed ways. Whereas Danto took on the idea of theory-dependence to explain the workings of art’s concept, others, working with a critical social theory, explored the dangers of this dependence the more a theory encouraged too great an ideological servitude to the most hardened of its concepts.

The matter of discernibility was taken up by the German Idealists around 1800 in their arguments regarding monochromatic formalism, repetition, and mediation. This is the matter of Part IV. From their vigorous debates, to which Kierkegaard contributed, an argument emerged to challenge the exclusive logic of either/or, allowing (the hyphenated) Jesus-Christ to be dynamically and surpassingly fully human and fully divine, of body and spirit, mortal and everlasting. So too for color, when red was said to absorb the difference of the not-red, to stand for the actual and the potential, the determinate and the indeterminate, or to appear as one color among others while universalizing and harmonizing the very idea and ideal of color. Working with notions of the mere, the more, and the all with respect to persons, artworks, and ordinary things is how Judeo-Christian thinkers in the West and Buddhist thinkers in the East have used the Red Sea anecdote to encourage contradictory predications. They have taken color seriously in artistic thoughts about form and design, especially sublime thoughts about

divine design. Thinking about color, they have pursued paths toward the emancipation from thinking and acting or living and dying in falsehood and error.

Diversionary Method. Over the last decade, unnervingly many books on the color red have been written. I borrow from their many insights and straightaway from Orhan Pamuk’s novel Benim Adım Kırmızı (My Name Is Red). Here, the claim of one’s name is threaded via biblical bloodlines to color’s first Adamic matter, worming, and cabling. With striking variation of detail and mood, Pamuk makes colors assume an agency witty and vengeful enough for each to become a suspect in an agonistic drama of murder and intensified city-description. Foregrounding what they give away of their innocence and guilt, he detects an old philosophical question: how a blind person comes to know color. Perhaps by comparative or abstract thought, or by hearing evocative descriptions or provocative explanations. Or maybe just by running into Pamuk’s persona named Red who verily claims to have been everywhere, in battles and in love, as illustration and ornament, in songs and dreams, and often by tramping in fields where intoxicating poppies bloom. Pamuk moves through different narrators to show contradictory characteristics of colors. I tackle the same movement more broadly. Together, however, we appeal to a long literary lineage of wit found in Rabelais, Molière, and Montaigne—later theorized brilliantly by Mikhail Bakhtin. I am drawn particularly to the lineage of not-so-vain subtleties, as when Pamuk gives his middle chapter to Red, the only chapter titled for Red, to mark the clever Uturn of Black’s passage of no return. In Part IV, I take up the red and the black, alongside the white and the grey, to expose conflicting monochromatic and formalist tendencies in philosophy and the arts—which then, in Part V, are shown to have inspired some of the most intriguing tellings of the Red Sea anecdote.

For my philosophical approach, I mostly follow Walter Benjamin’s manifestly modernist and materialist mode of enquiry as demonstrated in his Das Passagen-Werk. The English translation The Arcades Project captures the Parisian atmosphere while losing something that needs to be stressed: the advantage of juxtaposing different passages of thought and material in a single work. Benjamin offered indirect communications and colorful detours. He pursued the witty and melancholic ways of critique by using diversionary tactics and signposts to produce evocative and explosive constellations and thought-images (Denkbilder), insisting that they are hermeneutically truth-revealing in ways straight linear arguments cannot be. He collected elite and commonplace materials with a detective’s ear and eye, never ceasing to dig deeper into the stacks and drawers in libraries, museums, and secondhand shops. For my own detective work, I unpack the contributions of a philosophical furniture art to a modernist discourse on property. How does property come to pertain to thinking about the ownership of things as products of body and mind? How does talk about owning one’s