ForRichaandEstherLibby

Acknowledgements

TimLarsenaskedmetowritethisbookandhasstuckwithme throughmyslownessin finishingit.Histrustandadvicehavebeen indispensabletomethroughout.TomPerridgeatOxfordUniversity Presswasnotjustsimilarlypatientbutwasalsowonderfullyunderstandingin findingmesomeextrawordsatalatestageintheprocess. Ithasbeenapleasuretoworkagainwiththemeticulousandefficient KarenRaithonitsproduction.Iresearchedandwrotethisbookasa LecturerintheHistoryofChristianityinBritainattheDepartmentof TheologyandReligiousStudiesatKing’sCollege,LondonwhereI remainaVisitingResearchFellow.WhileatKing’sIwasparticularly gratefulforthekindsupportofPaulJoyceandMaratShterinasmy headsofdepartmentandforthecollegialityofDavidCrankshaw,my fellowlecturerinthehistoryofChristianity.Thegrantoftwoperiods ofresearchleavegreatlyadvancedmyworkontheproject,asdidthe awardofresearchfunding.TheGermanAcademicExchangeService DAADverygenerouslymademeagranttosupportaresearchtripto Germanarchives.

IwouldliketothankHerMajestytheQueenforpermissionto quotefromtheRoyalArchivesatWindsorCastle,whereIreceiveda gooddealofexpertassistance.Iamgreatlyindebtedalsotothestaffof thefollowinglibrariesandarchives:theArgyllpapersarchiveat InverarayCastle;theBritishLibrary;theStaatsarchivCoburgand theLandesbibliothekCoburg;theHessischesStaatsarchiv,Darmstadt;theArchivdesHausesHessen,SchlossFasanerie,Eichenzell; LambethPalaceLibrary;theNationalLibraryofScotland,Edinburgh;andDurhamPalaceGreenLibrary.

TheconvenorsofseminarsattheUniversityofOxford,the UniversityofCambridge,andtheInstituteofHistoricalResearch, Londoninvitedmetogivepapersaboutthisproject.Iamgratefulfor thefeedbackIreceivedonthoseoccasions.Ihavealsobenefitedfrom thechancetotalkaboutQueenVictoriaatconferencesandworkshopsinplacesasvariousasCambridge,Gotha,Haifa,Kensington Palace,Paris,Rome,andWaco,TX.

JonParry firstintroducedmetotheVictoriansasathirdyear undergraduateandhasbeenagreatsupporttomeinmyscholarly careereversince.Themanuscriptofthisbookhashugelybenefited fromhisreadingofit.Ilongagodespairedofmatchingtherigour, concision,andwryelegancewithwhichJonwritesaboutthenineteenthcentury,butIhopethisbooknonethelessembodiessomeofthe manythingshehastaughtme.MythinkingabouttheVictorians furtherdevelopedasamemberoftworesearchgroupsinCambridge: theCambridgeVictorianStudiesGroupandtheBibleandAntiquity inNineteenth-CenturyBritainproject.SimonGoldhill,theanimating spiritofbothgroups,showedtypicalgenerosityinreadinga first, unwieldydraftofthisbookandinprovidingmewithacute,challengingthoughtsaboutit.SotoodidJosBettsandIhavebenefited greatlyfromhistypicallyshrewdanalysis.Mythinkingabout nineteenth-centuryreligioninthisbookalsoowesmuchtotheconversationandfriendshipovertheyearsofGarethAtkins,ChrisClark, ScottMandelbrote,BrianMurray,andRobPriest.Ihavetriedto writeinwhatItaketobeoursharedconvictionthatthehistoryof religionistooimportanttobetakentooseriouslyandthatthespiritual kinksofnineteenth-centurypeoplecanbeasrevealingastheyare funny.IamgratefultoPhilipWilliamsonforsharingthenunpublishedresearchonstateprayerswithmeandtoAlexBremner,Joseph Hardwick,PeterHession,MeghanKearney,JamesKirby,Kate Nichols,andSimonSkinnerfordiscussionswhichpointedmetowards somesourcesandideas.Ihavelearnedalotabouttheimportanceof emotiontoreligioushistoryfromdiscussionswithmybrilliantPhD studentSamJeffreyandwithhissecondsupervisor,UtaBalbier.

Duringmyyearsofworkonthisbook,Ihavecountedonthe friendshipofPiersBaker-Bates,AlderikBlom,JamesCampbell, RosannaMariaDaCosta,SimonMills,RichardPayne,RoryRapple, JenniferRegan-Lefebvre,PernilleRøge,KatherineSpears,Zoe Strimpel,DavidTodd,andNickWalach.PiersdeservesspecialmentionforhiswillingnesstochasememoriesofQueenVictoriawithme, fromtheShahJahanMosqueinWokingtothetombsofNapoleonIII andthePrinceImperialatStMichael’sAbbey,Farnborough.While workingonthebook,IbeganshuttlingregularlybetweenLondonand Vancouver,beforemovingpermanentlytoBritishColumbia.That moveprovedtobeanexciting,butoftenastressfulanddisorienting

one,whichIcouldnothavepulledoffwithouttheloveandsupportof myparentsEileenandNigel,mybrotherandsistersStephen,Jen,and Abby,theirspousesPhoebe,Ben,andSimon,andmyniecesIndia andMatilda.ForwelcomingmeovertheyearstoVancouver,Iowe everythingtomyparents-in-lawGilaGolubandMarkDwor,my brother-in-lawYonahDwor,aswellastoAniaKorkhandRachel Laniado.GilaknowsmorethanIeverwillaboutthehistoryofthe BritishmonarchybutIhopethatthisbookwillnonethelesscontain somesurprisesforher.FormakingsureIcouldstayinVancouver, IamindebtedtomyimmigrationlawyerSamHyman.

ThiswouldbeaverydifferentbookandIwouldbeaverydifferent personhadInotmetRichaDworinthemiddleofwritingit.Although sheisherselfaneminentVictorianist,Richahasundoubtedlyhadto livetoolongwithQueenVictoria.Nonetheless,herloveandencouragement,whichneverfailedaswemovedfromQueen’sRoad PeckhamtojustoffVictoriaParkinEastVancouver,suppliedme withtheimpetusto finishthisbook.JustdaysafterIcompletedthe first draft,wewerejoinedbyourdearestdaughterEstherLibby,whohas spenther firstmonthspresidingquizzicallyoverits finalrevisions.Itis toRichaandEstherthatIdedicatethisbook.

Vancouver,BritishColumbia

August2020

ListofAbbreviations

APArgyllPapers,InverarayCastle,Argyll

BLBritishLibrary

CSACoburgStaatsarchiv

DPGLDurhamPalaceGreenLibrary

HHAHouseofHesseArchive,SchlossFasanerie,Eichenzell,Fulda

HSAHessischesStaatsarchiv,Darmstadt

LPLLambethPalaceLibrary

NLSNationalLibraryofScotland

QVJQueenVictoria’sJournalshttp://qvj.chadwyck.com/home.do

RARoyalArchives

RCINRoyalCollectionsInventoryNumber

WAMWestminsterAbbeyMunimentsRoom

Introduction

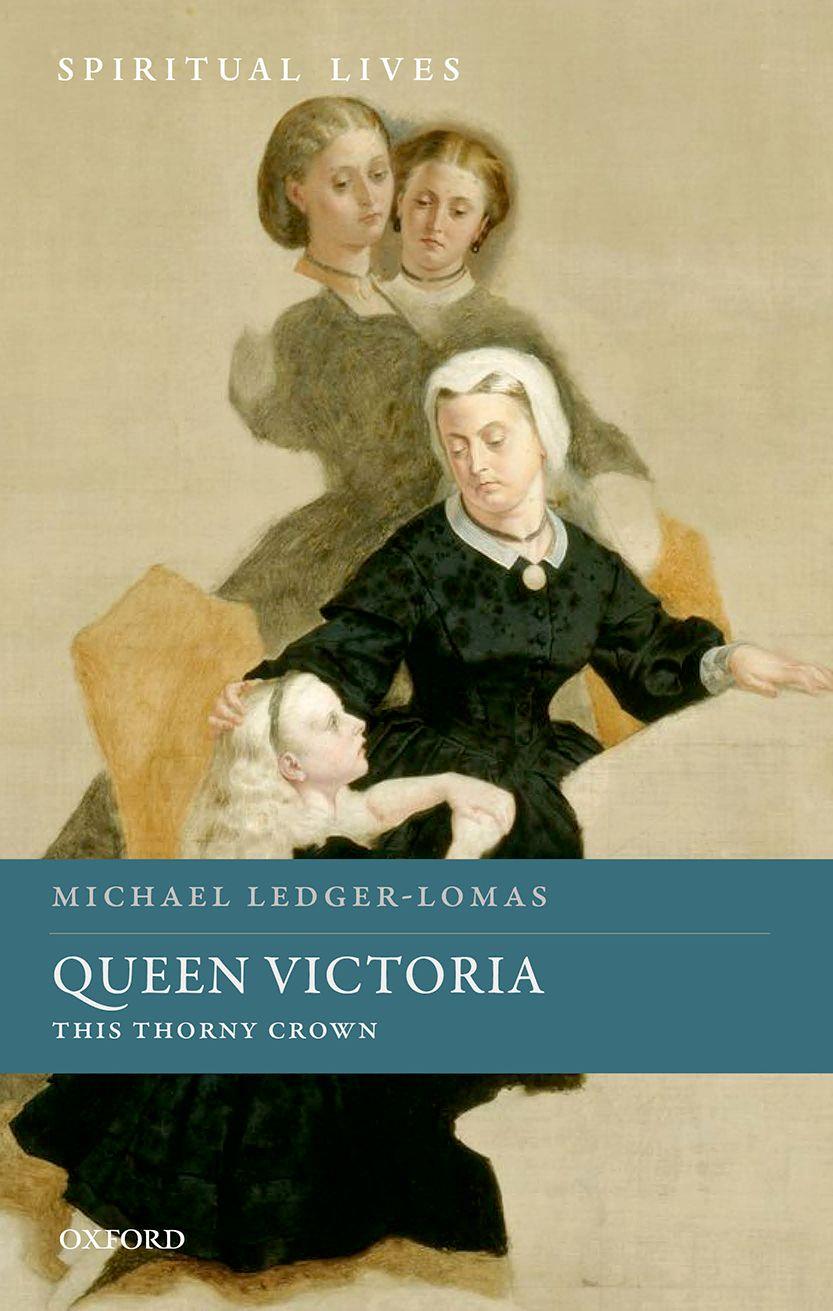

‘SomeoneTremendous’

PubliclifeinVictoria,BritishColumbia,revolvedarounditsnamesake whenthepainterEmilyCarrgrewupthereinthe1880s.TheQueen’ s birthdayinMaywasthemostimpressiveofciviceventsandimagesof herwereeverywhere.WhenCarr firstencounteredpicturesofVictoria’schildrenshewaspuzzled,becauseshehadknownheras

someonetremendous,thoughtomeshehadbeenvagueandfarofflike JoborStPaul.Ihadneverknownshewasrealandhadafamily,only thatsheownedVictoria,Canada,andthetwenty-fourthofMay,the ChurchofEnglandandallthesoldiersandsailorsintheworld.Now suddenlyshebecamereal – awomanlikeMotherwithalargefamily.1

IfVictoriawasasmuchpartoftheyoungCarr’ssettlercosmologyas ‘Jobor StPaul’,thenshewasalsoafragilepersonwhosereportedjoysandsorrows hadtestedherspiritualmettle.VictoriainducedinthecitizensofVictoria themagicalthoughtthatglimpsesintothelifeofanincrediblyremoteold ladycouldhelpthemsituatethemselvesinrelationtotheEmpireandthe world. ‘WithalmostnoneofusinthisProvincehassheevercomeinto contact’,musedVictoria’ s DailyColonist newspaperontheeveofher DiamondJubilee. ‘Yetallofusfeelthebetterandarethebetterforher strongandnobleconduct...[her]senseofresponsibilityunderGod.’2

TheintegrativeroleofVictoria’sspirituallifeinVictoria,British Columbiamatteredbecausereligiousfracturesranasdeepatthe marginsofherEmpireasinitsmetropole.WhileCarrrecognized VictoriaasthegovernoroftheChurch,herparentsdidnot.On Sundaymornings,sheandherfatherworshippedwithPresbyterians, whileintheeveningshewentwithhermothertohearEdward Cridge ananti-popishrenegadewhohadbecomebishopofthe PacificCoastintheReformedEpiscopalChurchofAmerica.3 The

seatofCridge’sdiocese,aCarpenter’sGothicchurch,wasjustoneof thetown’smanynon-Anglicanplacesofworship.Dissentingchapels proliferated,whiletheRomanCatholicStAndrew’sCathedralwas consecratedin1892.Thecity’soldestreligiousbuildingwasnot Christianatall,buttheTempleEmanu-Elsynagogue,whosecongregationsaidKaddishforVictoriaonthedayofherfuneralinFebruary 1901.4 ColonialsaccordedFirstNationsasubordinateplaceinthis royalcosmos.AftervisitingVictoriain1876,theGovernorGeneral LordDufferinhadsailedtoMetlakatla,amissionvillageonthecoast ruledwithdespoticbenevolencebyWilliamDuncan,who,like Cridge,wasarogueevangelicalwhohadrebelledagainsttheChurch. DufferininspectedMetlakatla’swoodenchurchandblithelyassured itsTsimshianresidentsthattheir ‘whitemother’ wouldprotectthem ‘intheexerciseofyourreligion,and...extendtoyouthebenefitof thoselawswhichknownodifferenceofraceorcolour ’ . 5 Victoriawas thenasymbolforpeopledividedonultimatequestions.Cridgehad stormedoutoftheChurchofEngland,buthestillgaveanaddressat thepan-ProtestantfestivalofthanksgivingatVictoria’sBeaconHill ParkonherDiamondJubileeandpronouncedthebenedictionatthe city’sopen-airmemorialserviceforheron2February1901.Onthat occasion,crowdshadsung ‘RockofAges’ , ‘NearermyGodtoThee’ , and ‘AbidewithMe’ infrontoftheblack-cladParliamentbuildings andunderanazuresky a ‘spontaneoussceneofloveandloyaltyto thedeceasedanddevotionandreverencetotheAlmightyFather whichcouldscarcelybeequalledanywhereonearth’ . 6

ThisspirituallifeofQueenVictoriaproceedsfromtheexpectation sharedbyherdividedsubjectsacrosstheEmpire:thatitbelongedto them.AstheBishopofLondonremindedVictoriaathercoronation, ‘ofnootherindividualmembersofthewholefamilyofmankindcanit besaid,withequaltruth,thattheylivenotforthemselvesalone,but fortheweal,orwoe,ofothers’ thanofmonarchs.Godmighthave distinguishedher,butexpectedmuchfromherinreturn,becauseher slightestfailingcouldshakethe ‘entireframeofsociety’ . 7 Thedesireto findlessonsinherlifewasthespringforthestreamofcontemporary biographieswhichhassincematuredintoanever-widening flood.

TheCanadianJohnW.Kirton’ s TrueRoyalty;or,theNobleExampleofan IllustriousLifeasSeenintheLoftyPurposeandGenerousDeedsofVictoriaas Maiden,Mother,andMonarch (1887)thusaimedtobeno ‘ mere

biography’,butrathera ‘“guide,philosopher,andfriend,” tothose whodesiretomakethemostoftheirtalents,opportunities,and powers ’ . 8 TheselivesoftenbentVictoria’spietytotheirsectarian commitments.Thefanaticallyanti-CatholicWalterWalshlaboured Victoria’sProtestantisminhis ReligiousLifeandInfluenceofQueenVictoria (1902),lamentingordismissinginstancesinwhichshehadbeensoft onRome.9 Modernscholarlybiographiesmayhaveleftthepietyand sectarianismofthehagiographersbehindthem,buthaveoftenlost theirawarenessthatreligionpervadedVictoria’slifeandthatitwas themediumthroughwhichhersubjectsthoughtaboutit.Whilethere arescholarlymonographsaplentywhichcontainexcellentevocations ofreligion’sroleinaspectsofVictoria’slife,thediscussionofVictoria’ s religionineventhemostcapaciousrecentbiographiestendstobe spottyandlackingincontextualization.10

IfexistingbiographiesoftenskimpintheirtreatmentofVictoria’ s religiouslife,thenthebiggerproblemisthatintheirconcentrationon herindividualwillandintereststheyareremotefromthemostincisive recentstudiesofVictorianmonarchy,whicheschewanarrowlybiographicalapproach.BuildingonLyttonStrachey’sclaimthatVictoria wasforVictorians ‘anindissolublepartoftheirwholeschemeof things’,historiansrightlyarguethat ‘whathappenedaroundthe monarchywasmoreimportantthanwhatthemonarchherselfdid’ andthatbiographiesalonecannotexplainVictoria’scentralityto Victorianculture.11 Recentstudiesofherroleinpoliticallife,her mediaimage,herrelationshipwithIndiaandthepeoplesofher Empireandherplaceintheimaginationofsuffragistcampaigners haverefinedandstrengthenedoursenseofVictoria’sagencyprecisely becausetheyemphasizethestructuralsupportsandconstraintsonit.12 AreligiousbiographyofVictorianeedstoplaceherwithinthese frameworks,whichwerenotjustBritishbutEuropean.TheEuropean nineteenthcenturywasanagenotjustofmodernizationbutof monarchy:itssovereignswerenotjustresilientinholdingonto power,butenterprisingin findingnewwaystoexpressand legitimizeit.13 Likehercrownedcontemporaries,Victoriaandher advisersassiduouslycommunicatedperceptionsofherlifeandcharactertohersubjects,whichwerepowerfulalthoughandbecausethey wereofteninaccurate.Eventhoughhistoriansoftenpresentroyal ‘soft power ’ asasecularcategory,onetiedupwiththeexpansionofthe

massmediaandthecultofcelebrity,religionremainedcentraltoit.14

IntellingthestoryofVictoria’sreligion,thisbookshowsthat,likeher lifeasawhole,itwasidiosyncraticbutneverprivate.15 WhatVictoria believedandhowsheworshippedreflectedherardent,partisan absorptionindebatesaboutchurch–staterelationsintheUnited KingdomandtheBritishEmpire.Atthesametime,Victorians demonstratedenormousconfidenceindiscussingtheinnermost secretsofherspiritualityandappealingtothemtovindicatetheir ownreligioustraditionsandfeelings.

ApproachingVictoriathenasbothanindividualandasasovereign,thebookpresentsher firstofallasachurchwoman.Onher accession,shebecamesupremegovernoroftheUnitedChurchof England,Wales,andIrelandandwaspledgedbyhercoronationoath tomaintaintheChurchofScotland.Likemanyofherpredecessorson thethrone,shenotonlygovernedtheChurchbuthadlearnedher personalpietyfromitandremainedcommittedtoitasanindispensableguarantorofsocialandpoliticalstability.Thoughshebecame andremainedaniconofBritishexceptionalism,Victoriawasno differenttootherEuropeanrulersinassumingthatherauthority wastiedupwiththevitalityofstatereligion. ‘Believeme,where thereisnorespectforGod nobeliefinfuturity therecanbeno respectorloyaltytothehighestintheland’,shewrotetoherdaughter Victoriain1878afteranembitteredsocialistshotatKaiserWilhelm IasherodealongUnterdenLindeninBerlin.16 Thisbookpresents Victoriaasanimportantactorincontroversiesoverchurchandstate, arulerdeeplyconcernedthroughoutherreignabouthownotonlyto defendestablishedchurchesbuttoremakethemintomoreProtestant andrepresentativeinstitutions.TheportraitofVictoria’spietythereforehasasitsbackgroundadetaileddiscussionofpolicy,embedding herintheclericalandgovernmentalnetworkswhichvariouslysupplied,encouraged,frustrated,andcriticizedherattemptstoreform nationalreligioninamulti-nationalUnitedKingdom.

EstablishedchurcheswerecentraltoVictoria’sreligiouslifenotjust becauseshecaredaboutthem,butalsobecausetheycaredabouther. Inhisseminal,sardonicaccountofpopularroyalismin TheEnglish Constitution (1867),WalterBagehotsuggestedthataroyalfamilymade governmentnotonly ‘intelligible’ tothecommonpeople,butalmost holy.Impressedamongotherthingsbypopularfervourforthe

marriageofVictoria’ssonthePrinceofWales,Bagehotarguedthat monarchy ‘strengthensourgovernmentwiththestrengthofreligion’ , ‘enlistingonitsbehalfthecredulousobedienceofenormousmasses’ . Thoughconfessingthat ‘itisnoteasytosaywhyitshouldbeso’ , Bagehotadvancedafunctionalistexplanation:adulationforthemonarchyworkedlikeareligionamongan ‘uneducated’ peoplewhich ‘wantseverynowandthentoseesomethinghigherthanitself ’ . 17 Bagehot,adisenchantedUnitarian,overlookedtheroleofthe churchesinhisdiscussionofreligion.Yet,asPhilipWilliamsonand othershaverecentlydemonstrated,theywereifanythingmoreactive inthesacralizationofthemonarchyinthenineteenththaninprevious centuries.18 TheChurchofEnglandorganizednationalthanksgivings forthehealthandlongevityofVictoriaandherfamily,withwhich ProtestantDissentersandevenRomanCatholicsassociatedthemselvesbothinBritainandthroughouttheworld.19 Victoriathusrelied asmuchasanyHabsburgorRomanovonherchurchtostage ‘scenariosofpower’.OnlyayearafterVictoriaprocessedthrough LondontogivethanksforherDiamondJubileeonthestepsofSt Paul’sCathedralforexample,theHabsburgEmperorFranzJosef walkedthroughViennaintheCorpusChristiprocessionthatmarked hisgoldenjubilee.20

AlthoughthebookemphasizesVictoria’secclesiasticalcommitments,italsosuggeststhatherrelationshipwithreligiousVictorians becamejustasaffectiveasitwasinstitutional.ThecrusadingDissentingjournalistW.T.SteadarguedatthetimeoftheDiamondJubilee thatshehadbecomethehead,notmerelyofthe ‘narrowsectof Anglicanecclesiasticism’,butof ‘theCivicChurch theUnionofall wholoveintheserviceofallwhoSuffer’ andthe ‘headandIdeal Exemplar’ ofthe ‘Family’,whichwas ‘thebroadestandmostcatholic Churchofall’ . 21 Investigationsintonineteenth-century ‘livedreligion’ oftendiscoverthatlaypeopleengagedinpracticesorprofessedbeliefs notaccountedforbyclericalnorms.22 Victoria’slifewasofthiskind. HistoriesofVictorianreligionoftenconcentrateontheriseandfallof churchparties,thecompetitionbetweenorthodoxiesortheirerosion throughsecularization.Itishardto fitVictoria’slifeintosuchmodels: sheunderstoodreligionnotastheperformanceofritesorasadherencetodoctrinesaboutthesupernatural,butratherasanimmanent faiththatfounditshighestexpressioninromanticanddomestic

emotions.ThedeathofherhusbandPrinceAlberton14December 1861,whichbiographershavealwaysrecognizedasadecisiveturning pointinherlife,onlydeepenedtheemotionalthrustofherreligiosity anditsaccessibilityforhersubjects.Victoria’sperformanceofgrief andresignationturnedthespiritualandemotionalburdensofthe sovereignintothejustificationofherrule:apotentsourceofsoft powerandapowerfulanswertothenaggingquestionofwhata constitutionalmonarch,andafemaleoneatthat,didallday.23 It allowedherhagiographerstorepresenthertocongregationsand readerswhomightnotbelongtoherchurchastheir ‘Queen-mother andfriend ’ andtocastrepublicanismasthefailingof ‘callous ’ people whocouldnotfeelforthis ‘largeheartsofullofcompassionfor others’ . 24 InstudyingVictoria’sreligiousfeelings,thisbooksuggests thattheyalignedthemonarchywiththeincreasingtendencyof believerstoregardfeelingsratherthantruedoctrinesastheessence ofpiety,andsharedemotionsasthebondofreligiousandnational communities.25

ThisbookalsoarguesthattheexpansionandideologicalconsolidationofVictoria’sEmpiremadeherreligiositynotjustnationally, butgloballysignificant.AssettlercolonieswongreaterpoliticalautonomyfromWestminsterbutcontinuedtofeelpartofGreaterBritain, theyfoundinVictoriaa fittingexemplificationofthevirtueswhich theyfelthadcontributedtoitsexpansion.26 Thiscult,whichreached itsapogeeinhertwoJubileesof1887and1897andherfuneralin 1901,wasnotjustakindofcivicreligionbutamanifestationof imperialChristianity.TheChurchofEngland’sincreasinglyelaborate colonialchurchesandcathedralswerenaturalvenuesforroyalritesof thanksgivingandsorrowthroughouttheEmpire.27 Presbyterians, ProtestantDissentersandRomanCatholicsgenerallyprovedtobe nolessavidintheirroyalism,whichallowedthemtoasserttheir prominenceincolonialsocietiesandtheirglobalsolidarityalikewith otherBritonsandwiththeirdiasporicchurches.Wewillseethat colonizedpeoples,bothChristianandnon-Christian,alsoaccepted thatitwaspossibletoenterintoemotionalcommunitywithQueen Victoria.Settlersandtheirclergylovedtotalkoftheloveofnative peoplesfortheir ‘GreatWhiteMother ’,whichhandilyobscuredthe realitiesofwhitecolonialviolenceanddomination.Yetevenifhistoriansrightlysuggestthatimperialrulerestedsquarelyontheexerciseof

terror,thisbookwillshowthatitoftensuitedcolonizedpeoples,both Christianandnon-Christian,tousethereligiousrhetoricoflove,not leastbecauseitallowedthemtodemandactionagainsttheevils inflictedonthembyimperialism.28

InweavingtogetherVictoria’sreligiouslifewiththedevelopmentof popularideasaboutit,thisbookdrawsuponmanysources.Itrests aboveallonasystematicreadingofVictoria’snowdigitizedjournal, whichshebeganinJuly1832andkeptupdailyuntilshortlybeforeher deathinJanuary1901.Itslimitationsasasourceareobvious.Mostof itexistsonlyinherdaughterBeatrice’stranscriptions,whichdoubtless deletedsomesensitivepassages,whileitsshallownesscanbeeven morefrustratingthanitsomissions.WhileVictoriawasoftenstirred towritevoluminouslyaboutHighlandsscenery,foreigntravel,or theatricalandmusicalproductions,shewasoftenreticentabouther encounterswiththetextsandideasthatexcitereligioushistorians.To takejustoneexample,sherecordedon8August1852that ‘Albert toldmemuchaboutaninterestingbookheisreading,the “Lifeof Jesus” byStrauss. Dinnerasyesterday. ’ Yetifthediary’scoverageof Victoria’sreligiousinterestsisnotdeep,thenitisunusuallyextensive, especiallywhenreadinfull.Ifsheseldomcommentedmuchonthe bookssheread,orwhichwerereadtoher,shewasassiduousinnoting theirtitles.29 Shehabituallyrecordedthenamesofthosewho preachedtohereverySundayandsummariesoftheirsermons.This makesitpossibletoreconstructtheclericalnetworksandtextswhich mediatedVictoria’sknowledgeofthechurchesandnationalreligion andshapedherfeelingsaboutthem.ThebookdrawsuponVictoria’ s publishedandunpublishedcorrespondencewiththechurchmen whoinspiredherandwithherprimeministersandotherstatesmen to fleshoutitsaccountofthesenetworks.WhileVictoriacouldbe arbitrary,evencantankerous,inexpressingherwillinreligiousmatters,thesesourcesshowthatshedependedcloselyonadvice fromthoseshetrusted,fromhouseholdclergysuchastheDeansof WindsorGeraldWellesleyandRandallDavidsontosuchstalwart servantsasherprivatesecretaryCharlesGreyandthemenofletters ArthurHelpsandTheodoreMartin.Thebookdrawsontheirwritingsandunpublishedpapersandcorrespondencetoevoketheir resoluteliberalProtestantism,whichmingledwithandoftenstrengthenedVictoria’ sown.

Thebook’ssystematicreadingofVictoria’sdiaryalsogeneratesan inductivepictureofwhatreligionmeantforher.Itsentriesshowthat Victoriaresembledmanyofhersubjectsingivingmoreimportanceto spacesandthings fromphotographsandstatuestotombsandpersonalrelics thantotextualbeliefsinthedefinitionandexpressionof religiousfeeling,especiallywhenitcametomourningthedead.30 As LyttonStracheysaw,Victoriawasawomanof ‘innumerablepossessions’;ahoarder ‘notmerelyofthingsandofthoughts,butofstatesof mindandwaysoflivingaswell’ . 31 Thebookthereforecontinually attendstothereligiousspacesandobjectsthatVictoriaused,built,or collected,fromprivatechapelsandmausoleumstoportraitsand prayerbooks,evokingtheassociativesensibilitythatinformedher piety.Victoria’scorrespondencealsogeneratesawidervisionof whatshedefinedasreligiouslife.Ifthisbookhasemployedthethick bindersoflettersattheRoyalArchiveslabelled ‘Church’ andwhich areprimarilydevotedtotheconductofecclesiasticalbusiness,thenit alsodrawsonherlifelongexchangeswithfemalecorrespondents:her daughtersVictoriaandAlice,herGermansister-in-lawAlexandrine, herauntLouise,theQueenoftheBelgians,andmanyfriendsand courtiers.ThegentlemeneditorsofVictoria’sselectedpublished correspondencedidnotincludemany ‘LettersfromLadies’,asthe RoyalArchiveslabelledmuchofthismaterial,preferringtorepresent herasanhonorarystatesmanwhowasmainlyintentonpublic business.32 Yetalthoughlargelyprivateandsentimental,ratherthan politicalorostensiblytheologicalinscope,thiscorrespondenceisa valuablesourceforVictoria’sreligion.Itshowshowsheandher friendsandrelativesformedanemotionalcommunitywhosespiritual languageofresignationbeforethetrialsoflifeoftencrossednational andconfessionalboundaries.33

ThebookmobilizesdifferentkindsofsourcestoshowhowVictoria featuredinthereligiousimaginationofVictorians.Literary,cultural, andgenderhistorianshavealreadydemonstratedthatthematerialfor suchaninvestigationishuge,giventhevolumeofwritingabout Victoria,thequantityofengravedandthenphotographicimagesof herandofcommoditiesproducedtomarkherJubileesanddeath.34 Thisbookexploresthereligiousmeaninganduseofsuchsources,but alsoconcentratesonanothertextualsource:theVictoriansermon. EverymajoreventinVictoria’slifeoccasionedasalmonrunof

printedsermonsandtracts,patterningherexperiencesonScripture, themasternarrativeforChristianlives.35 Becauseeven ‘boilerplate’ languagerevealstheclustersofconceptsandfeelingsthatsocietiesand theirleadersvalue,theseproductionsareavitalsourceforthisbook, even,andperhapsparticularlywhen,theyarerepetitiveandbanal.36 Preacherssawthemselvesaschargedwithensuringthattheintense emotionsarousedbycrisesinVictoria’slifestrengthenedtheholdof theircongregationsonreligioustruth.Thisbookasksnotwhetherthe wordsofsympathyandvenerationshoweredonVictoriaweresincere, butratherwhatpreachershopedtoaccomplishinutteringandthen publishingthem.AlthoughAnglicanpreachersassertedaproprietorialrelationshipwiththemonarchy,Dissenting,RomanCatholic,and Jewishpreachingcouldbeequallyandjustasrevealinglyroyalist. BeneaththeconsensusthatVictoriaincarnatedvirtueandreligion a consensusthatwasremarkableinitself sharpdifferencesemergedin whatreligiouscommunitiesfeltherrulemeantforthem.Althoughthe mostconfidentspeakersofroyalistlanguagewerewhiteProtestant Christians,thebookexploreswhatotherreligionssaidabouthertoo, suggestingthattheirwordsoffealtywerenomereactsofimitationbut attemptstoadvancetheirpositionwithintheEmpire.

ThisbooktellsthestoryofVictoria’sreligiouslifethroughaseries ofinterlinkedessays,whicharearrangedinlooselybutnotstrictly chronologicalform,becausewhileitisimportanttoconveyhowtime andtheaccidentsoflifechangedVictoria’sreligion,manyofher preoccupationsmustbetracedacrossdecades.The firstchapterof thisbook(‘ANewReign’)setsoutthereligiousexpectationson Victoriaatheraccessionin1837.Ifsheinheritedherdynasty’ s commitmentstothemaintenanceofProtestantismandtheestablished church,thenshewasalsosubjecttothenewemotionalintensitywith whichreligiouspeopleregardedtheirmonarchs.Thishadbeenevidentinthepublicreactiontothesuccessivedeathswhichclearedher waytothethrone.ReactionstoVictoria’scoronationandtoassassinationattemptsagainstherearlyinherreignshowthat,asthelast Hanoverian,shetoowasasacral,providential figure,althoughshe quicklydistancedherselffromthepoliticalProtestantismofherpredecessors.ThenextchapterstracethedevelopmentofVictoria’ s personalreligionanditsdivergencefromtheHanoveriantemplate. Thesecond(‘MeinezweiteHeimat’)arguesthatVictoria’smarriage

toAlbertinstilledinheraProtestantidenti ficationwithGerman Lutherans.DynastictiesnotonlyopenedVictoriatoGermaninfluences,butbecamethemediumthroughwhichsheandAlbertsought tobuildreligiousandpoliticalaffinitiesbetweenBritainandGermany.HavingoutlinedthetransnationalparametersofVictoria’ s Protestantism,thethirdchapter(‘ReligioninCommonLife’)sketches thedevelopmentofherliberalProtestantcommitmenttolivedlay religion,whichoverlookedconventionaldistinctionsbetweenthe sacredandthesecular.VictoriaandAlbertregardedfamilyand home,ratherthanthechurch,asthelocusofreligiousfaithand practice,andsoughttoadvancetheidenti ficationofGodwiththe lawsofhiscreation.Thefourthchapter(‘ADarkenedEarth’)shows howthedestructionofVictoria’shouseholdthroughdeathtestedher faith,promptingananguishedsearchforspiritualandmaterial sourcesofconsolation,whichalarmedherfriendsandadvisersbut alsocreatedanewtemplateforpopularattitudestothethrone. Victoria’sinsistencethatshehadareligiousobligationtopileup evermorebaroquemonumentstoherhusband’svirtueseventually generatedresistanceandscepticism,although,aslaterchapterswill show,herwidowhoodbecameanenduringsymbolofhersoftpower, whichallowedpreacherstowaxeloquentonherlonelysuffering.

DomesticrepresentationsofVictoriaaswife,motherandwidow becamesoimportantinthereligiousimaginationthattheycan obscurethedegreetowhichsheremaineda fiercelyengagedecclesiasticalpolitician.HistoriansincreasinglyreturntoFrankHardie’ s seminalinsightthatVictorianotonlyreignedoverVictorianBritain, butremaineddeterminedtoruleit,particularlywhereherpatronage powerswerestillmoresubstantialthanconventionalemphasesonthe developmentofa ‘democratic’ constitutionalmonarchyallow.37 The fifthchapter(‘TheSupremeHead’)discussesVictoria’sdeep,fractious relationshipwiththeChurchofEnglandandWales.Shecametothe thronedeterminednotjusttomaintain,butalsotoreformtheChurch bypromotingtheliberalclergywhocouldmakeitamorecharitable andrepresentativeinstitution.Resistancetotheroyalpromotionof liberalismbyTractariansandRitualistswholoathedProtestantism andErastianism statemeddlinginspiritualmatters madeher increasinglyaggressiveinherdeterminationtobroadentheChurch, asshepressedforlegislationtostampoutliturgicalexperimentswhich

hintedatahankeringafterRome.Victoria’ sfeelingthatshecould defendtheChurchbymakingitmorerepresentativeoftheProtestantnationnotonlysetheragainsthighchurchpeople,butblinded hertotheprincipledobjectionsmanyProtestantDissentersnursed toitsestablishment.HeralarmedresponsetotheirtalkofdisestablishmentfurthernarrowedVictoria ’ sunderstandingofliberalism.

Thesixthchapter( ‘ DisunitedKingdom ’ )turnsfromVictoria’ s effortstoenforceProtestantconsensusinEnglandandWalesto herrecordincopingwiththereligiousdiversityoftheUnited Kingdom.EvenifVictoria’ svisionoftheChurchofScotlandwas asparochialashervisionofScotlanditself,bothbeingcentredon theHighlandsparishofCrathie,itbenefi tedherandtheUnion. AlthoughherfriendshipswithKirkministersmadeherabiased participantindisputesoveritsest ablishedstatus,impressionsof Victoria’ ssympathywithScottishreligionsankdeepinScotland andaroundtheEmpire.Victoriahadhopedshemightcommend herselftotheIrishasshedidtotheScots,bypayingrespecttotheir differentnationalreligion,butthechaptershowsthatherestrangementfromIrishRomanCatholicsmountedwithherreluctanceto crosstheIrishSea.ThoughappreciativeofRomanCatholicismasa livedreligionandfriendlytowardspopes,notleastbecauseshe hopedtheymightbringtheIrishCatholichierarchytoheel,Victoria couldnottranslatethesepersonalaf fi nitiesintoaconstructivepoliticalrelationshipwithCatholicIreland.

LyttonStracheyoncewrotethatVictoria’sbiographermustagree withherinseeingherlongwidowhoodas ‘anepiloguetoadramathat wasdone’,shroudedin ‘darkness’ anddeservingonlya ‘briefand summaryrelation’ . 38 Biographieshaveoftentacitlyendorsedthat judgement,seeingthefortyyearsthatfollowed1861asatimeof waningambitionsandvitality.Bycontrast,thelastchaptersofthis bookpresentthemasaperiodofreligiousinnovation.Theseventh chapter(‘TheCrownofSacrifice ’)suggeststhatwhileacrescendoof bereavementsmadeVictoriaagloomyandretrospectivepersonand sovereign,theybolsteredherspiritualcredentials.Thelavishwayin whichsheburiedandcommemoratedhermalerelativesmadeherthe Empire’smournerinchief,aligningafemininemonarchywiththe increasinglymilitaristicandimperialcharacterofelitecultureaswell aswiththesofteningofChristianeschatology.Theeighthchapter