https://ebookmass.com/product/principles-of-rockdeformation-and-tectonics-jean-luc-bouchez/

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Regional Geology and Tectonics: Principles of Geologic Analysis: Volume 1: Principles of Geologic Analysis 2nd Edition Nicola Scarselli (Editor)

https://ebookmass.com/product/regional-geology-and-tectonicsprinciples-of-geologic-analysis-volume-1-principles-of-geologicanalysis-2nd-edition-nicola-scarselli-editor/ ebookmass.com

Welding Deformation and Residual Stress Prevention Ninshu Ma

https://ebookmass.com/product/welding-deformation-and-residual-stressprevention-ninshu-ma/

ebookmass.com

Severe Plastic Deformation: Methods, Processing and Properties Ghader Faraji

https://ebookmass.com/product/severe-plastic-deformation-methodsprocessing-and-properties-ghader-faraji/

ebookmass.com

An Eye-Tracking Study of Equivalent Effect in Translation: The Reader Experience of Literary Style 1st Edition Callum Walker

https://ebookmass.com/product/an-eye-tracking-study-of-equivalenteffect-in-translation-the-reader-experience-of-literary-style-1stedition-callum-walker/ ebookmass.com

Fate of Biological Contaminants During Recycling of Organic Wastes Kui Huang https://ebookmass.com/product/fate-of-biological-contaminants-duringrecycling-of-organic-wastes-kui-huang/

ebookmass.com

The Billionaire Orc: A steamy and sweet monster romance (Motham City Monsters Book 3) Lilith Stone

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-billionaire-orc-a-steamy-and-sweetmonster-romance-motham-city-monsters-book-3-lilith-stone/

ebookmass.com

Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America W. Caleb Mcdaniel

https://ebookmass.com/product/sweet-taste-of-liberty-a-true-story-ofslavery-and-restitution-in-america-w-caleb-mcdaniel/

ebookmass.com

Media and Communication in the Soviet Union (1917–1953): General Perspectives Alexey Tikhomirov

https://ebookmass.com/product/media-and-communication-in-the-sovietunion-1917-1953-general-perspectives-alexey-tikhomirov/

ebookmass.com

Beginning R 4 - From Beginner to Pro Matt Wiley

https://ebookmass.com/product/beginning-r-4-from-beginner-to-pro-mattwiley/

ebookmass.com

You Had Me at Wolf Terry Spear

https://ebookmass.com/product/you-had-me-at-wolf-terry-spear-2/

ebookmass.com

PRINCIPLESOFROCKDEFORMATION ANDTECTONICS PrinciplesofRockDeformation andTectonics Jean-LucBouchez

UniversityofToulouse

AdolpheNicolas

UniversityofMontpellier

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford,OX26DP, UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries

FirstpublishedinFrenchas Jean-LucBouchez,AdolpheNicolas Principesdetectonique ©DeBoeckSupérieurs.a.1eédition2018 EnglishTranslation©OxfordUniversityPress2021 Themoralrightsoftheauthorshavebeenasserted Impression:1

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,withoutthe priorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rightsorganization.Enquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,atthe addressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress 198MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY10016,UnitedStatesofAmerica BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData Dataavailable

LibraryofCongressControlNumber:2021936318

ISBN978–0–19–284387–6 DOI:10.1093/oso/9780192843876.001.0001

Printedandboundby CPIGroup(UK)Ltd,Croydon,CR04YY

LinkstothirdpartywebsitesareprovidedbyOxfordingoodfaithand forinformationonly.Oxforddisclaimsanyresponsibilityforthematerials containedinanythirdpartywebsitereferencedinthiswork.

Prefaceandacknowledgements Thisbookisinheritedlargelyfromthe PrincipesdeTectonique, writtenbyAdolphe Nicolas(Masson,1983)whorecentlypassedaway(April2020),andfromarecent PrincipesdeTectonique (J.L.BouchezandA.Nicolas,DeBoeck,2018).

Itisanup-to-dateandaugmentedversionthatkeepstheconciseandrigorouswriting ofitsinspiringpredecessor.Itisbasedonlaboratoryandfieldexperienceofbothauthors, withafocustowardshardrocksandmagmaticrocksfromboththecontinentalcrust worldwideandthemantle,principallyfromtheOmanophiolites.

Thebookhasmorethan250figures,mostofwhichareoriginal.Inadditiontoclassic geologicalsubjects,thebookincludeselementssuchasplasticdeformationandfabric acquisitioninrocksandmagmas,measurementandorientationofstress,togetherwith basicbackgroundinformationonneotectonics,geophysicsandotherpracticaltoolssuch asmagneticfabricsnotcommonlytreatedingeologicalbooks.Sincethetargetedreaders arepresentdayyoungstudents,afewexercisesofstructuralgeologyareincludedto improvetheirabilities.

Ourcolleagues,ProfessorManishA.MamtanifromtheIndianInstituteofTechnologyatKharagpur,India,andProfessorRichardD.Law,professoratVirginiaTech, USA,havecloselyassistedtheauthorstoexpelmostofthe‘gallicisms’andotherflaws fromtheEnglishmanuscript.

Severalcolleagues,friendsandinstitutionshavecontributedtothesuccessfulcompletionofthisbook:

– ChristianeCavaré,a Paganini indrawingsandlayouts,whopermanently,patiently andkindlyhelpedtheauthorstocompleteeveryfigure,nevercomplainingabout changesuptomanuscriptcompletion;

– Ourlaboratories(GéosciencesEnvironnementToulouse and GéosciencesMontpellier), andUniversities(UniversitéToulouse-Midi-Pyrénées and UniversitédeMontpellier), whereforover30yearstheauthorshadallfacilitiestoaidteachingandresearch;

– OurstudentsfromFranceandmanyotherscountries,Brazil,UK,Iran,Portugal, Spain,Belgium,Cameroon,Madagascar,Ethiopia,USA,…,whogaveussomuch, andhelpedustoprogress;

– ManycolleaguesatToulouse,especiallymypartner,ProfessorAnneNédélec, andatMontpellier,particularlyProfessorFrançoiseBoudierwhostronglyassisted AdolpheNicolasduringsomanyyears.Shehelpedinthewritingandpolishingofseveralchapters.ProfessorAlainVauchez,DavidMainprice,Anne-Marie BoullierandMaurineMontagnat,seniorscientistsattheCNRS(NationalCentre forResearch)atMontpellierandGrenobleuniversities.Allofthemarewarmly acknowledged;

vi Prefaceandacknowledgements

– Ourformerpublisher,DeBoeck-Sup,whoconfidentlygaveuscreditforthe Frenchedition, PrincipedeTectonique; – SonkeAdlung,ourcommissioningeditoratOUP,forhisconstantencouragements.

Jean-LucBouchezandAdolpheNicolas Massat(FrenchPyrenees) April2020

1.1.5Progressivedeformationanddeformationregimes

1.1.6Flowlinesandvorticitynumber

1.1.7Shortening,extensionandstrainmeasurement

2.3.6Frommicrofracturestofractures:thefatiguephenomenon

2.4.1Directstressmeasurements

3

3.2.1Fibreorientationandincrementalstrain

3.2.2En-échelontensiongashes

3.2.3Tensionfracture-faultrelationships

3.3.1Geometricalanalysisoffaultsandfault-systems

3.3.2Faultinternalstructures

3.4.1Stressreconstructionfromfaults

3.4.2Stateofstressaroundafaultandfaultassociation

3.4.3Complexsystemsandsecondaryfractures

4Ductiledeformationandmicrostructures

4.2.4Slipsystems

4.2.5Recrystallization:dynamic,static,primary,secondary

4.2.6Structuralpalaeo-piezometers

4.2.7Deformationexperimentsandflowlaws

4.4Fluid-assistedflowmechanisms

4.4.1Pressure-solutiondeformationmechanisms

4.4.2Deformationexperimentsandflowlaws

4.5Localizationofdeformationandshearzones

4.6Afewdistinctivemicrostructures

5.1Afewnotionsaboutfolds

5.2.1Cleavage,schistosityandfoliation

5.2.2Slatycleavage,crenulationcleavageandfracturecleavage

5.2.3Minerallayeringandtectoniclayering

5.2.4Cleavage-foldrelationships

5.2.5Strainellipsoid–C/Sstructurerelationships

5.3 Linearstructures

5.4Relationshipsbetweenlineations,foldaxesandstrainellipsoids

6Fabricsandkinematicanalysisofquartzites,iceandperidotites

6.1Developmentofpreferredorientations

6.1.1TheEtchecoparmodel

6.1.2Heterogeneousdeformationofcrystals

6.2Coaxialandnon-coaxiallatticefabrics

6.3Fabricrepresentation:theorientationdiagram

6.5Examplesoffabrics

6.5.1Quartzfabrics:fromthelaboratorytothefield

6.5.2Icefabrics

6.5.3Olivinefabrics

6.6Pastandpresentmantleflow

6.6.1ThelherzoliticLanzomassif

6.6.2FrozenmantleflowbeneaththeLanzomassif

6.6.3ThediapirsoftheOmanophiolites

6.6.4Seismicanisotropyofthemantle

7.1Somerheologicalaspects

7.1.1Theimportanceofviscosity

7.1.2Newtonianbehaviourofmagmasinplutonsand emplacementscenarios

7.2Microstructures:magmatic,orthogneissic,mylonitic

7.3Magmaticfabricacquisitioninplutons

7.3.1Buildingamagmaticfabric:fromcrystaltomagma

7.3.2Magmaticfoliationsandlineations

7.4Magmaticfabricsinplutons

7.4.1ThePlouaretgranitecomplex(Brittany,NWFrance)

7.4.2TheBjerkreim–Sokndallayeredintrusion(Norway)

7.4.3TheTesnougranitecomplex(W-Hoggar,Algeria)

7.5Injectionsinmagmaticcomplexes:mixingandmingling

7.6TheBushveldandSkaergaardmaficcomplexes

7.6.1StructuresandmicrostructuresintheBushveldand Skaergaardcomplexes

7.6.2DynamiclayeringintheSkaergaardcomplex

7.7Gabbrosfromtheoceaniccrust

8 Rheologyofthelithosphereandstatesofstress

8.1Rheologicalprofileofthelithosphere:theChristmastree

8.2Mechanicalanisotropyofthelithosphere

8.2.1Superimposedanisotropy

8.2.2Inheritedanisotropy

8.3Focalmechanismsofearthquakes

8.3.1Focalmechanismdiagrams,orbeachballs

8.3.2Focalmechanismsandmaintectonicregimes

8.3.3FocalmechanismsattheHimalayanfront

8.3.4Focalmechanismsinthecontextofobliquesubduction

8.3.5FocalmechanismsatthejunctionbetweentheSan AndreasandGarlockfaults

8.4Stressconcentration

8.5FromthestressbulbtotheIndianindenter

8.6StatesofstressinFranceandaroundtheWorld

9.1Horizontaldisplacementsandrates

9.1.1Horizontaldisplacementsalongsub-horizontalsurfaces

9.1.3Horizontaldisplacementsandtheirslip-rates

10.8 Anisotropyofmagneticsusceptibility(AMS)

11.1ApplicationofMohrdiagraminstructuralgeology

11.1.1StressanalysisandMohrcircle

11.1.2StrainellipseandMohrcircle

11.1.3ApplicationtothetruncatedbelemnitesofFigure1.11

11.1.4ApplicationtothedeformedbrachiopodsofFigure1.12

11.2Internalinclusionsingarnets

11.2.1Heliciticgarnet:shearstrainandsenseofshear determination

11.2.2AgarnetfromtheIsledeGroix(W.France)

11.3Introductiontoorientationdiagrams

11.3.1Intuitiveplotofaline(A),ofaplane(B)

11.3.2Preciseplotofaline,orpole,ofaplane

11.3.3Rotationoforientationdata

11.4Foldaxisconstruction:anexamplefromthefield

11.5Unravellingstructureentanglements

11.5.1Lookingforanoriginalorientationfromaglacialerratic

11.5.2Lookingformineralizedcolumnsinamine

11.6Lookingforpaststatesofstress:palaeostressanalysis

11.6.1Analyticaltechniquesfordynamicanalysis

11.6.2Geologistlookingforastateofstress

11.7LookingforsuccessivestatesofstressintheLefkasregion (Greece)

11.8Lookingforalocalstateofstress

11.9Isostasy,theverybaseofverticalmovements

Deformation/strainandstress Twowordsareusedtodescribetheresultofastress:‘deformation’and‘strain’. Deformationisageneraltermdescribingthechangeofshape,sizeand/orpositionof anobject,whilestrain(or‘internal’deformation)isusedwhenassociatedwithsome quantificationofshapechange.(NotethatinFrench, deformation isusedforboth meanings.)

Nostress,nodeformation.Letusbeginwithdeformation,whichistheconsequence ofapplyingsomestress.Inthefollowingsection,however,symbolsreferringtoastress willnaturallyappearhereandthere.Theynametheprincipaldirectionsofpush(σ1) andpull(σ3).

1.1 Deformation 1.1.1 Afewdefinitions

Anobjectsubmittedtoexternalforcesmaybethesubjectofadeformation.Deformation isa transformation,alsocalled displacement (initsbroadestsense).Adisplacement canbesplitintoa distortion,a translation anda bulkrotation.Itshouldbenoted thatonlythedistortionalpartofadisplacementisresponsibleforthechangeofshape ofanobject.

Let’sconsiderasetofpointsbelongingtoanobjectbeforedeformation(pointsof origin)andthesamepointsofthedeformedobject(endpoints).Thevectorsconnecting thepointsoforigintotheendpoints,called displacementvectors,forma displacementfield (Figure 1.1).Ifthedeformationisatranslation,allthedisplacementvectors equalthevectordefiningthetranslation.Thishappenswhenathrustsheetrigidlymoved onasurface;thegeologistwilltrytodeterminethetranslationvector(intensity,azimuth andsense)inordertolocateitsorigin.

Ifthesurfaceonwhichthethrustsheetmovedwascurved,forexamplesteepeningupwardstowardstheEarth’ssurface(e.g.,itsdipincreased),abulkrotationwas addedtothetranslation(Figure 1.1b),aroundahorizontalaxisforthechosenexample. Sometimesthegeologistislookingfortheelementsthathelptocharacterizeabulk rotation,alsocalledrigidrotation,characterizedbyarotationaxis,anangleandasense ofrotation.Suchresearchisperformedusingpalaeomagnetictools.Thesetoolsare

(a) (c)

Figure1.1 Fieldsofdisplacementvectors:(a)foratranslation(bodyhasnotaccommodatedstrain); (b)forabulkrotation(herealso,bodyhasnotaccommodatedstrain);(c)foradeformationincluding adistortion,i.e.,strainedbody).Thestrainpathisdotted.

currentlyappliedatplatescales,suchastheopeningoftheAtlanticOcean,therotationoftheIberianPeninsulawithrespecttoEuropeorrotationoftheCorsica–Sardinia blockwithrespecttoItaly.Palaeomagnetictoolscanalsobeappliedtoevensmaller geologicalobjectssuchascrustalblocksalongstrike-slipfaults(seeFigure 9.6).

Iftheshapeofanobjectchangesafterdeformation,thedisplacementvectorsvaryin orientationandmagnitudefromonepointoftheobjecttotheother(Figure 1.1c);they aresubjectedto displacementgradients reflectingadistortion.Distortionisgenerally calleddeformation,changeofshapebeingthemainsubjectofstudy.Thereisnothing tosaythattranslationsand/orbulkrotationsmay,ormaynot,havealsotakenplace. Thesetwocomponentsofdeformationaregenerallydifficulttoevaluateduetoalackof appropriatemarkers.Apreciseknowledgeofthedisplacementfield,forinstanceinthe caseofanalogueexperiments(Figure 1.6),allowsustoretrievethethreecomponents ofdeformation.

Mathematically,theanalysisofdeformationisperformedwiththehelpoftensors(see§ 10.1).Thedisplacementtensoristheadditionofthreetensors:translation, rotationanddistortiontensors.

NotethatthedisplacementvectorsofFigure 1.1 providenoinformationonthe strain path,representedasdottedpathsinthefigure.Thestrainpathcorrespondstoasuccessionoftectonicevents(compression,extension,strike-slip).Iftheshapeofadeformed objectiscomparedtoitsoriginalshape,usuallyunknownexceptinanalogueexperimentsorwhenfossilssuchasammonites,trilobitesorbelemnitesareconcerned,a homogeneousdeformation inwhichstraightlinesremainstraightlinesduringdeformation(Figure 1.2a)canbedistinguishedfroma heterogeneousdeformation (Figure 1.2b).Inthefirstcase,thedeformationisobviously continuous,whilein thesecondcasethedeformationmaybecontinuousaswellaslocally discontinuous (Figure 1.2c).Thediscontinuitymaybeperhapsagrain-boundary,ajoint,afracture, orafault.Notethatadeformationmaybecontinuousatthescaleofamassiforan outcrop,anddiscontinuousatthescaleofasample,thinsectionorelectronmicroscope

Figure1.2 Deformation:(a)continuousandhomogeneous;(b)continuousandheterogeneous; (c)discontinuous.

Figure1.3 Penetrativedeformation:(a)atagivenscaleofobservation;(b)atanotherscale.

observation,sincemultiplediscontinuitieswillappearatthosescales.Therefore,adeformationmaybe penetrative atthescaleofanoutcrop(Figure 1.3a),i.e.,itappears toaffectthewholevolumeunderobservation,and non-penetrative athighermagnifications(Figure 1.3b).Thishighlightstheimportanceofscaleinstructuralgeology.

1.1.2 Finitestrain/finitestrainellipsoid Thesimpleststrainmeasurement,thelongitudinalstrain,favouredbygeologists,consistsincomparingagivenlengthofanobjectbefore(L0)andafter(L1)deformation. Totalstrain,or finitestrain,isgivenby:

ε = (L1 L0)/L0 orinpercent: ε% = ε × 100

Engineersinmechanicsprefertoconsidertheaddition(theintegral)ofallthe(infinitesimal) deformationincrements;theyusetheso-called‘natural’strain:

Deformation/strainandstress Otherstrainmeasurescanbefoundsuchas(inonedimension)stretchorconversely, contraction: ε =L1/L0 (or ε%=(ε −1)×100),quadraticelongation: λ2 =(L1/L0)2.Note thatastretchingvalueof100%(i.e.,doublingtheinitiallength)doesnothavethesame consequenceasashorteningvalueof100%(disappearanceoflength).Thesameapplies atthestockexchangewhereagainof100%doublestheprofit,whilealossof100%does nothalvethebet!Notethatallthesestrainmeasuresaredimensionlessandtherefore havenounitattachedtothem.

Finitestrainisgenerallyrepresentedbyanellipsoid.Considerarockcontaining spherical,millimetre-sizedcalcareousorferruginousconcretions(i.e.,ooliths).Afterdeformationoftherock,theoolithsbecomeellipsoidalinshape.Ifthedeformationwas homogeneousandpervasive,anyrandomlychosenoolithcharacterizesthedeformation, thedistortionmoreprecisely,oftherockcontainingtheooliths.Strainmeasurementis performedbycomparingtheshapeandsizeoftheellipsoidwithrespecttotheinitial sphere.Theellipsoidiscalledthe finitestrainellipsoid (Figure 1.4),using finitestrain inthesenseof totalstrain,thatis,resultingfromthecomparisonbetweentheundeformed(original)anddeformed(final)states.Bycontrast,adeformationthatwouldbe consideredstepbystep,thatis,incrementally,isreferredtoasaprogressivedeformation (see§1.1.5).

Thethree principalaxesX ≥ Y ≥ Z ofthefinitestrainellipsoidconstitutethe structuralframe ofthegeologicalobjectunderstudy(Figure 1.4).Finitestrainiscommonly consideredtobeconstantvolume,or isovolumic.However,insomecasesdeformation maybeaccompaniedbyagainofvolume,or dilatancy (Figure2.16),butmoregenerally byalossofvolume,forexampleduetofluidexpulsionsuchascompactionofsediments orchangeinrock-formingmineralsduetodehydrationunderprogrademetamorphism. Providedthatadeformationishomogeneous,strainmaybequantifiedintherock byusing strainmarkers suchasfossils,dykes,pebbles,ooliths,oxidationorreduction spots.Strainmeasurementsaimtodeterminethelengthratiosbetweentheprincipal axesofthestrainellipsoid.Ideally,suchmeasurementsareperformedalongthethree principalplanesoftheellipsoid(Figure 1.4),namelyXY(foliation),XZ(perpendicular tofoliationandparalleltolineation)andYZ(perpendiculartolineationandtofoliation). Inthecaseofaheterogeneousdeformation,suchmeasurementsarerepeatedinside domainsoftherockformationwheredeformationisconsideredashomogeneous.Strain measurementshavereachedahighdegreeofsophisticationowingtojudiciouschoices

Figure1.4 Thestrainellipsoid:itsprincipalaxes(X ≥ Y ≥ Z)definethestructuralframe.

ofstrainmarkers(see§ 11.1 and 11.2)and/ortoelaboratemathematicalprocessing (see§ 10.1).

1.1.3 Typesofdeformation Theshapeofthestrainellipsoid,flatorelongate,determinesthe typeofdeformation. WhenadeformationdoesnotmodifythelengthoftheYaxis,meaningthatalldisplacementstakeplacealongtheXZplane,thedeformationisa planestrain.TheFlinnor Woodcockdiagrams(Figure 1.5)convenientlyhelptoquantifythedifferenttypesof deformation.

IntheFlinndiagram(Figure 1.5a),whichgraphicallyrepresentsconstantvolume strain,X/YisplottedasafunctionofY/Z.Theslopeofthestraightlinepassingthrough (1,1)allowsustodefinetwodomains:the flatteningdomain,betweenpureshortening (K=0;pancakeshape;Zisarevolutionaxis,orsymmetryaxis)andplanestrain(K=1), andthe stretchingdomain,betweenK=1andpureelongation(K=infinity;cigar shape;Xisaxisofrevolution).ThesameprinciplesholdfortheWoodcockparameter thatqualifiesthestatisticalshapeofpopulationsofobjects,orfabrics(seeChapter 6).In theWoodcockdiagram,theshapeellipsoidischaracterizedbytheparameterk,which rangesfrom+1to−1,through0forplanestrain(Figure 1.5b),adifferencethatmay satisfythosefavouringsymmetry!Inbothdiagrams,theintensityofdeformation(strain) isrepresentedbythedistancetotheorigin.

1.1.4 Analogueexperiments Themechanicalbehaviourofrocks,adisciplinealsocalled rheology,maybestudiedthroughanalogueexperiments,usingtwodifferentapproaches.Thefirstconcerns simulationsusing small-scalemodels builtwithanaloguematerials.Thesemodels

Figure1.5 Shaperepresentationsofstrainellipsoids:(a)Flinndiagram(usedforindividualobjects); (b)Woodcockdiagram(usedforacollectionofobjects:E1,E2 andE3 representtheeigen-valuesofthe fabrictensor).

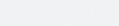

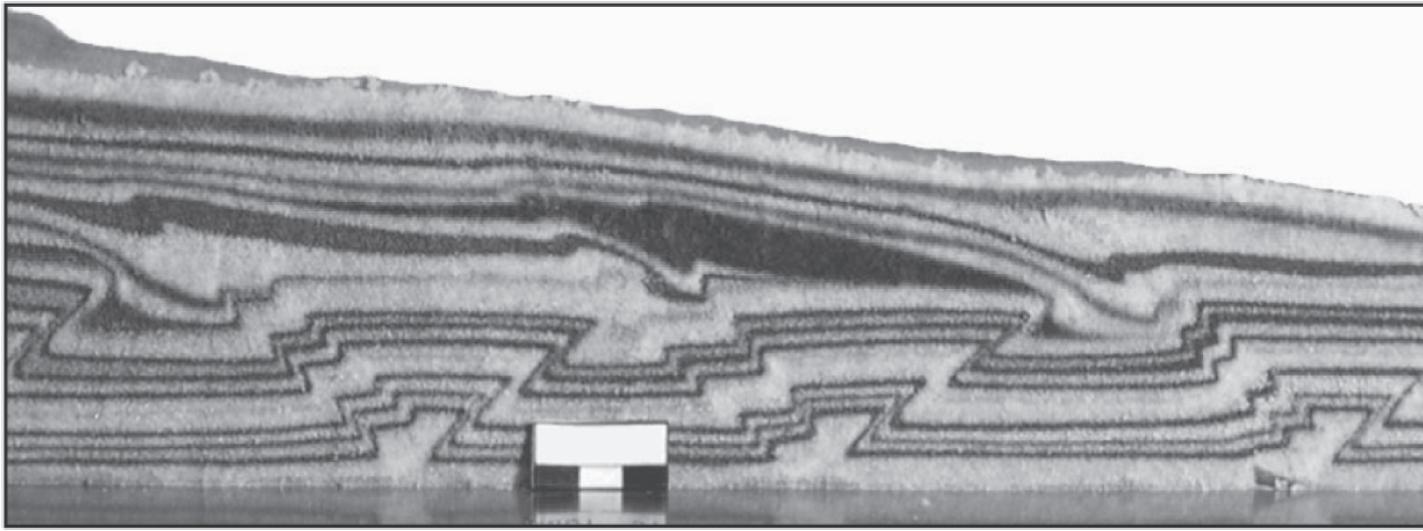

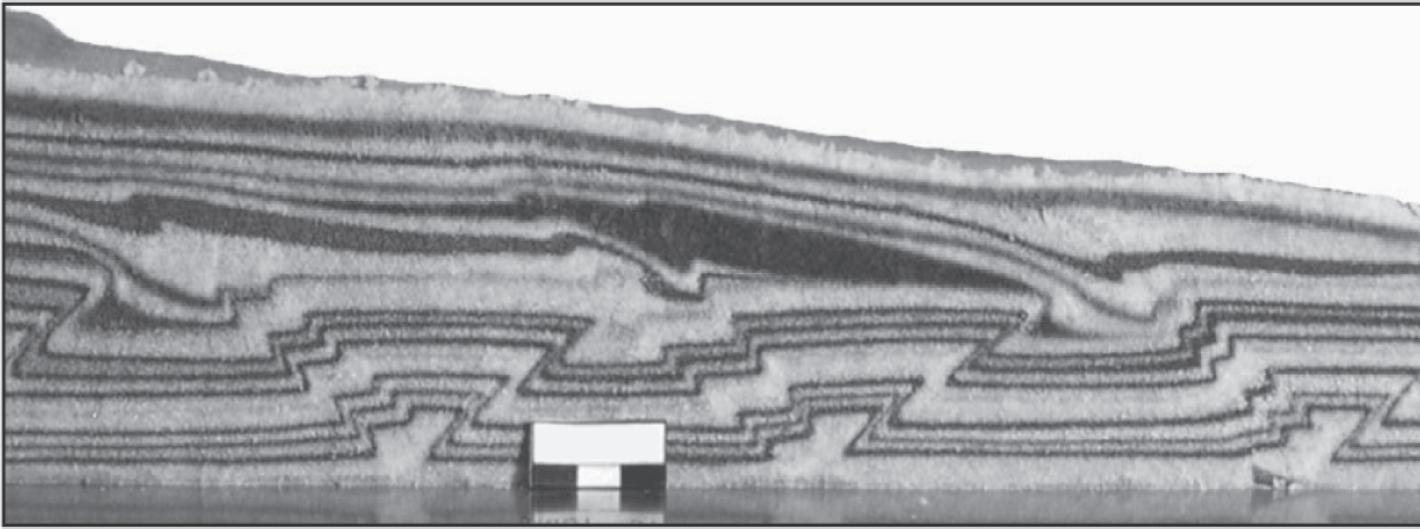

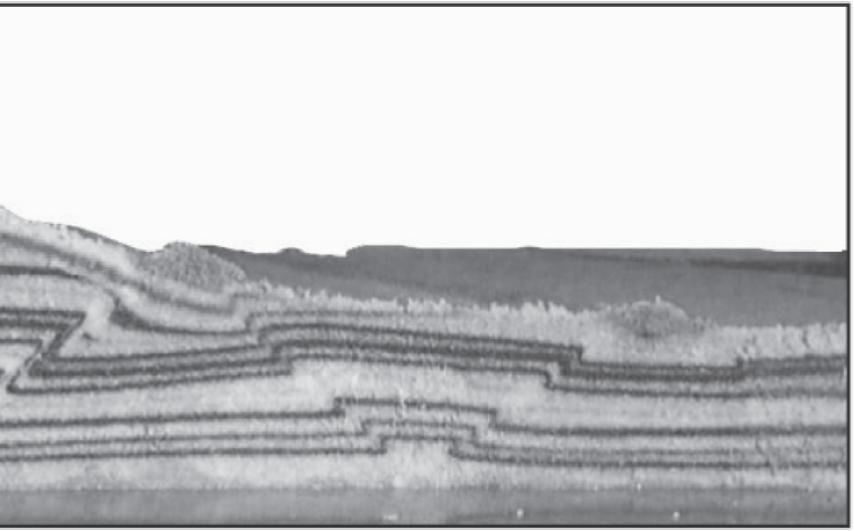

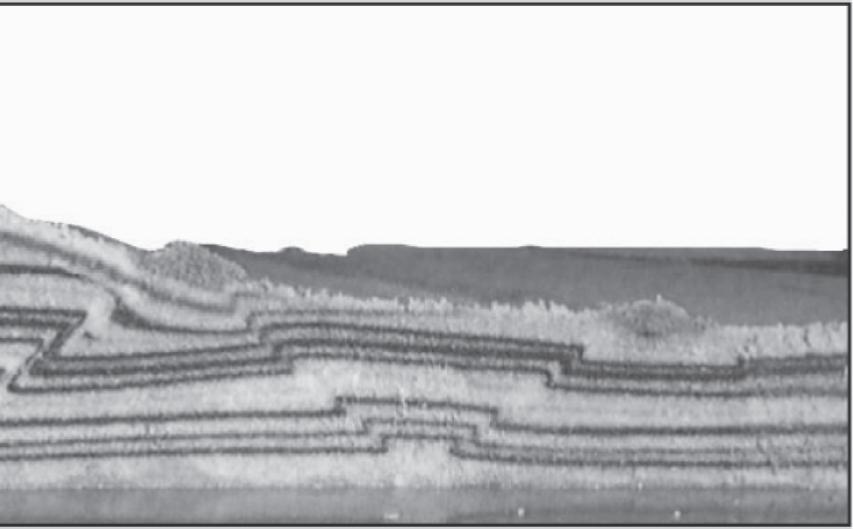

Figure1.6 Analogueexperiments.(a)HansRamberg’sexperiment (modifiedfromGravity, deformationoftheEarth,LondonAcademicPress,1981),thestartingpointofseveralstudieson diapirism,showingthesuccessivestagesofalayerofoiltoppedbyalayerofsyrup.(b)Sandlayersof differentcolourspushedfromtheleftsideandsimultaneouslysubjecttosedimentdeposition. (With permissionofFrancisOdonne,professorattheUniversityofToulouse.)

attempttoreproduce,inthelaboratory,naturalsituationsthatarecomplexprincipally becauseoftheirgeometry,durationandrateofdeformationandphysicalproperties. Formationandevolutionofadiapir(Figure 1.6a),ofamineralfabricinamagma(see § 7.3),ofaconvectingsystem,ordevelopmentoffoldsandfaultsinapileofsediments (Figure 1.6b),allfallundertheapplicationofanaloguemodelling.

Analoguemodelsarerealisticprovidedthatthe analoguematerials arechosen judiciouslyconsideringtheirmechanicalproperties(density,viscosity,frictioncoefficient,etc.).Accordingtothesituationunderexploration,thegeologistuseshoneyor siliconepastetosimulateaviscousdeformation,andsandormicrospheresforbrittle deformation.Moregenerally,thescalingofexperiments,intime,spaceandphysical properties,isrealizedusing dimensioningprocedures,or scalingrules thatallow quantitativecomparisonstobemadebetweenthemodelandreality.

Theotherapproachinvolves mechanicaltests ofrocksorminerals.Thesetestsaim todetermine,forexample,thestrengthlimitofamaterialunderbrittleconditions(in compression,tension,torsionorflexure),oritsbehaviourunderductileconditionsat hightemperatureandpressure.Acubeofsoiltransformedintoaninclinedprismby simpleshear(Figure 1.7a)orarockcylindertransformedintoabarrelbyaxialcompression(Figure 1.7b)arecommontestsperformedinlaboratoriesforthebehaviour analysisofbuildingmaterials.Testsatroomtemperatureandpressurearecommon incivilengineering(buildingofroadsandbridges,etc.).However,thegeophysicist,

Figure1.7 Mechanicaltests:(a)insimpleshear;(b)inpureshear.Thesetermsareexplainedinthe followingsection.

whoseaimistounderstandthebehaviouroftheEarth’scrustandmantle,usesanapparatusabletodeformasmall(afewcm3)cylindricalspecimenofrockormineralat hightemperatureandpressure,forexampleinanapparatusliketheGriggsmachine (Figure 1.14).

1.1.5 Progressivedeformationanddeformationregimes Anydeformationdevelopsthroughtheadditionof increments.Fromthispointofview thedeformationis progressive.When,duringaprogressivedeformation,theellipsoid axesremainparalleltoeachotherateachincrement,thedeformationissaidtobe coaxial.A pureshear experimentperformedinthelaboratoryunderahydraulicpress (Figure 1.7b),alsocalledpureflatteningbygeologists,correspondstoacoaxialdeformationsincethecompressionandstretchingaxesremainconstantinorientationduring deformation(Figure 1.8a).Dividingthe2Dspaceintoshorteningandextensionsectors, theseparationlinesbetweensectorsremainunchangedduringacoaxialdeformation (Figure 1.9a). Puresheartectonicregimes arelocallypresentincompressiveorogenic areas.

Incontrast,whentheprincipalaxeschangeinorientationduringdistortion,the deformationissaidtobe non-coaxial.Obviously,thisisacommonsituation,since itisdifficulttoimaginethattheaxesoftheincrementalellipsoidsremainstrictlyparallel toeachother,particularlyduringalargedeformation.Amongtheinfinityofpossible non-coaxialdeformations, simpleshear (Figures 1.7a and 1.8b)isbyfarthemost common non-coaxialdeformationregime.Quantifiedbyashearangle(θ)or shear strain (γ =tan θ),simpleshearisa planestrain,meaningthattheYaxisisinvariant, allthedisplacementvectorsbeingconfinedtotheXZplane.Duringsimpleshearing, theXandZaxesoftheincrementalellipseskeepaconstantorientationat±45◦ from theshearplane,whichisitselfinvariant.Asaconsequence,atthebeginningofsimple shear(θ =0◦+),theveryfirstextensiondirectionXmakesanangleof α =45◦ withthe shearplane(Figure 1.8d).Duringthenextincrements, α decreasesprogressivelydown to0◦ foraninfiniteshear(θ =90◦; α =0◦)accordingtotherelationtan θ =2cotan2α (Figure 1.8d).

Figure1.8 (a)Pureshear,(b–d)simpleshear.(aandb)Consideringtheprincipalstressdirections(σ1 and σ3)asfixed,incoaxialdeformation(a)theZandXprincipalstrainaxesremainparallelto σ1 and σ3,respectively;incontrast,theyprogressivelyrotateinthecaseofnon-coaxialdeformation.Notethat deformationishomogeneous,astraightlineremainingasastraightlineduringprogressivedeformation; (c)Apackofplayingcardswithamarkerlineillustratessimpleshearofangle θ;byslidingalongthe shearplaneeachcardcontributestothedextralrotationofthemarkerline;(d)relationshipbetweenthe shearangle( θ)andtheangle(α)betweentheextensiondirectionandsheardirection.

1.1.6 Flowlinesandvorticitynumber AlookatFigure 1.8 showsthatthefinitestrainellipseforsimpleshearissimilarto thatofpureshearexceptfortheorientationofitsaxes.Intermsofdeformation,this similarityismisleadingbecausethepathsfollowedbytheparticlesformingthematerialaredifferent.Byanalogywithfluids,inpureshearthe flowlines followedby theparticlesdivergeonsidesofthecompressionaxis(β =90◦;Wk =cos β =0; Figure 1.9a)whiletheyremainparalleltotheshearplaneinthecaseofsimpleshear (β =0◦;Wk =1;Figure 1.9c).Wk iscalledthe kinematicvorticitynumber,and β representstheanglebetweentheimaginarylinesseparatingtheflowsectors,called flow apophyzes,inFigure 1.9.Pathsofparticleslyingbetweentheflowsectorswouldrotateby90◦ (β =90◦)inpureshear(Wk =0)andwouldnotrotate(β =0◦)insimple shear(Wk =1).Intermediateregimesbetweenpureshearandsimpleshear(Figure 1.9b),oftenreferredtoas‘sub-simple’shearor‘general’shear,arecharacterizedby 0<Wk <1.

Inordertodetermineifadeformationwascoaxialornot,onemustbeable,using markers,toretrace,atleastpartly,thedeformationpath(dottedlinesinFigure 1.1). Indeed,thisisexceptional.Inpractice,thefabricsofkeyminerals,suchasolivinein

pureshear Wk=0

b =90°

b =60° b =0 Wk=0.5simpleshear Wk=1

Figure1.9 FlowslinesandvorticitynumbersWk.Wk = 0inpureshear;Wk = 1insimpleshear (dextralinthiscase).

mantlerocksorquartzincrustalrocks,providequalitativeindicationsaboutthenoncoaxialityratioofthedeformation.ThisaspectofvorticityisdevelopedinChapter 6.

1.1.7 Shortening,extensionandstrainmeasurement Let’sconsiderapuresheardeformationintwodimensions(Figure 1.10a).Thesectors facingthecompressionaxisaresubjectedto shortening,whilethosefacingthetensile axisaresubjectedto extension.Inotherwords,underprogressivepureshear(coaxial strain),materiallinesorientedat0◦ to±45◦ withrespectto σ1 willalwaysbeshortened whilethoseat±45◦ from σ3 willalwaysbesubjectedtostretching. Insimpleshear,thelattersituationholdsonlyatthebeginningofdeformation(for θ valuescloseto0◦;Figure 1.10b):atthattime,sectorsfacingthecompressionaxisare undershortening.Withincreasingsimpleshearing,theshortening/stretchingsectors progressivelyrotateawayfrom σ1,upto45◦ for θ =90◦ (infiniteshearstrain),dextrally fordextralsimpleshear.Thisexplainswhytheaxes σ1 andZ(or σ3 andX)makean angleinFigure 1.8b.Theseanglesincrease(upto45◦)withincreasingstrain.

Figure1.10 Compressive(shortening)sectors‘c’(black);versusextensive(stretching)sectors‘e’(white) for:(a)pureshear,and(b)simpleshearfrom θ = 0◦ (onsetofdeformation)to θ = 90◦ (infiniteshear strain).

Deformation/strainandstress Figure1.11 Principalaxes(X,Z)ofthestrainellipse,asdeterminedinorientationsandmagnitudes fromthreebelemnites(A,B,C)observedontoacleavageplane (InspiredfromJ.G.Ramsay,1967, Foldingandfracturingofrocks,McGraw-Hill).Seetheexercise§ 11.1.3.

Onemayeasilycalculatethatalineparalleltothecompressionaxis(σ1)of Figure 1.8b wouldbeshortenedbyabout30%aftersimpleshearingof θ =45◦,then stretchedbyabout106%ifshearingwouldcontinueupto θ =70◦.Asaconsequence, ingeologicalformationssubjectedtosimpleshearing,materiallinessuchasdykes, foldeddykesandstretchedpreviouslyfoldeddykesmaybeobserved,dependingon shearstrainintensityandtheirinitialorientationwithrespecttotheimposedstress axes.

Considernowsetsofdeformedobjectsresultingfromeitherpureshearorsimple shear.Acommonexerciseforastructuralgeologistwouldbetodeterminethestrain ellipseresponsibleforthesedeformedobjects.Insomefavourablecases,suchasamong theblackschistsfromBourgd’Oisans(France),thestrainellipseaxesonthecleavage planemaybedetermined,bothinorientationandmagnitude,usinglinearobjectssuchas belemniterostrums(Figure 1.11).Similarly,theangularvariationsoflinesfromobjects whoseoriginalshapesareknown,suchasbrachiopodsdepositedonabeddingsurface,

Figure1.12 PrincipalstrainaxesdeterminedoutofthreedeformedbrachiopodtestsA,B,andC (InspiredfromJ.G.Ramsay,1967).Seetheexercise§ 11.1.4

allowustoretrieveinformationrelatedtotheorientationandlengthratiooftheaxesof thestrainellipse(Figure 1.12).

1.2 Stress 1.2.1

Stressellipsoid LetusconsideracylindricalspecimensubjectedtoaforceFappliedperpendicularlytotheoppositefacesS(Figure 1.13a).Thisforceisresponsibleforapressure (P=F/S= σ1)called normalstress.This stressregime issaidtobe uniaxial. Amorecomplexexperienceconsistsinsubjectingthespecimentodistinctstresses (Figure 1.13b), σ1 normaltoSaspreviously,and σ2 = σ3 orientedperpendiculartothe cylinder’saxis.Inmechanics,thisstressregimeissaidtobe triaxialwithasymmetry ofrevolution (i.e.,revolutionwithrespecttothecompressionaxis).

IntheexperimentofFigure 1.13b,itcanbesaidthateverysurfaceelementofthe specimenissubjectedtoanormalstress σn whileanadditionalstress σ = σ1 σn is appliedtotheopposite,circularfacesofthespecimen.Thisextrastressisresponsible foradeformation(distortion)andiscalled differentialstress,ormoresimplystress.

Amoregeneralsituation,representedinFigure 1.13c,iswhenthreedifferentnormal stresscomponents, σ1 ≥ σ2 ≥ σ3,areappliedtothethreecouplesofoppositefaces ofaparallelepipedrectangle.Suchastressregimeiscalled puretriaxial.The mean pressure, isotropic or hydrostatic stressisdefinedasPhydro =1/3(σ1 + σ2 + σ3),and theprincipaldifferentialstressesas σ1 −Phydro, σ2 −Phydro and σ3 −Phydro.Notethat lithostatic ispreferredtohydrostaticascharacterizingtherockloadexistingatdepth. Thepressureduetotherockloadbecomesisotropicatdepth,wheretherocksbehave likea(highly)viscousfluid.Inrockdeformationexperimentsathightemperatureand pressure,forinstancewiththe Griggsapparatus (Figure 1.14),thegeophysicistcalls confiningpressure theisotropicpressureappliedtoaspecimen,usingtalcorhalite (dependingontheexperiment)astheconfiningmedium.

Figure1.13 Stressregimesappliedtoaspecimen:(a)uniaxial;(b)triaxialwithsymmetryof revolution(pseudo-triaxial);(c)puretriaxialand(d)thestressellipsoid.

Deformation/strainandstress inner piston outer piston insulating foil

Axial load

hydraulic chamber oil

hydraulicram

pressurecell watercooling sample assemblage and confining medium

20cm

Figure1.14 LoadingsystemoftheGriggsapparatus(designedbytheAmericangeophysicistDavid Griggs,1911–1974).Thepiston-cylindersystem,pressurizedbytheaxialload,deliversaconfining pressureupto2GPa,adifferentialstressofafewMPaandtemperaturesupto1200◦C.Thehydraulic ramtransmitstheconfinement,andtheinnerpistonisresponsibleforthedifferentialstress.Thesample assemblagecomprisestheconfinementmedium(talcorsalt),agraphitefurnace,oneortwo thermocouplesandacylindricalspecimen(rockormineral)ofafewmmindiameterand10–20mmin length.

Inmathematicalnotation,thestressappliedatapoint,or stateofstress,isexpressed byatensorhavingsixindependentcomponents(see§ 10.2).Geometrically,itisrepresentedbyanellipsoidwhosethreeaxesrepresentthethreeprincipalnormalstress axes σ1 ≥ σ2 ≥ σ3 (Figure 1.13d).TheconfiningpressurePlitho,duetotheloadofthe overlyingrocks,isaverticalforcewhosevalueis:

Plitho (pascalunit,Pa) =1/3 (σ1 + σ2 + σ3) = ρ gz

ρ beingtherockdensity(2400–3300kg/m3),andg,theaccelerationduetogravity (9.81m/s2).

Intheabsenceoftectonicforces,closetotheEarth’ssurfaceandatlowdepths,the horizontalstressvaluesare σ2 = σ3 <Plitho.Assoonasacertaindepthisreached,ofthe orderofafewkilometres,theconfiningpressurebecomesisotropic σ1 σ2 = σ3 =Plitho. Atthatdepth,thatis,belowtheso-called brittle–ductiletransition,theearth’smaterialbecomesductileinbehaviourduetoshearstressrelease.Schematically,thestress ellipsoidevolvesfromasmallrugbyballpointingverticallyatlowdepthintoalarge soccerballatgreaterdepth(Figure 1.15).

brittle–ductile transition (b) (a)

Figure1.15 Statesofstresscomparisonbetween(a)sub-surfaceand(b)depth.In(a)themajor principalstresscomponent(σ1)isvertical,duetotherockload;in(b)theprincipalstresscomponents becomesimilarinvalueowingtoshearstressrelaxationatdepth.Thebrittle–ductiletransitionzone (hachured),rangesfrom10to20kmindepth,dependingonthegeothermalgradient,fluid-pressure anddeformationmechanisms.

1.2.2 Normalstressandshearstress Anormalstressconsidereduptonowisstrictlyequivalenttoapressuresinceitisapplied perpendicularlytomaterialsurfaces.Whenasurfacehasarandomorientation,thecomponentofastressactingparalleltothissurfaceisthe shearstress (ortangentialstress). Hence,astressactingonasurfacenaturallysplitsintotwocomponents,a normalstress andashearstress.Thisdefinitionillustratesthatastressisnotapressure,despitehaving thedimensionsofaforcedividedbyasurfacearea.

Letuscalculate,intwodimensions(axes1and3),thecomponentsofastressapplied toX,apointbelongingtoasurfaceelementSS′ obliquelyorientedwithrespecttothe forceF1 exertedonfaceA(Figure 1.16)oftherectangle.Thisforceresolvesintoa normalcomponent,Fn1 =F1 sin α,andatangentialorshearcomponent,Ft1 =F1 cos α,allowingustodeducethevaluesof σn1 =Fn1/SS′ (withSS′ =A/sin α)and τ1 = Ft1/SS′.ConsidernowaforceF3 exertedonB,thefaceperpendiculartoA.Thetwo componentsFn3 andFt3 become σn3 =Fn3/SS′ and τ3 =Ft3/SS′ (withFn3 =F3 cos α, Ft3 =F3 sin α andSS′ =B/cos α).Therefore,thestresscomponentsatXbecome σnx = σn1 + σn3,and τx = τ1 + τ3.Thisleadsto: σnx =F1/Asin2 α +F3/Bcos2 α = σ1 sin2 α + σ3 cos2 α

τx =F1/Acos α sin α −F3/Bsin α cos α (negativesignindicatesthatF3 counteractsF1 atX).