https://ebookmass.com/product/predator-ecology-evolutionaryecology-of-the-functional-response-john-p-delong/

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Evolutionary Parasitology: The Integrated Study of Infections, Immunology, Ecology, and Genetics 2nd Edition

Paul Schmid-Hempel

https://ebookmass.com/product/evolutionary-parasitology-theintegrated-study-of-infections-immunology-ecology-and-genetics-2ndedition-paul-schmid-hempel/ ebookmass.com

Fundamentals of Soil Ecology 3rd Edition

https://ebookmass.com/product/fundamentals-of-soil-ecology-3rdedition/

ebookmass.com

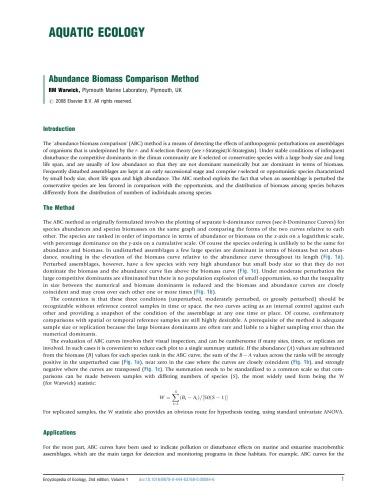

Encyclopedia of ecology 2nd Edition Fath

https://ebookmass.com/product/encyclopedia-of-ecology-2nd-editionfath/

ebookmass.com

Writing the Brain: Material Minds and Literature, 1800-1880 Stefan

Schöberlein https://ebookmass.com/product/writing-the-brain-material-minds-andliterature-1800-1880-stefan-schoberlein/

ebookmass.com

Leadership and small business : the power of stories

Hutchinson

https://ebookmass.com/product/leadership-and-small-business-the-powerof-stories-hutchinson/

ebookmass.com

Contract Farming, Capital and State: Corporatisation of Indian Agriculture 1st Edition Ritika Shrimali

https://ebookmass.com/product/contract-farming-capital-and-statecorporatisation-of-indian-agriculture-1st-edition-ritika-shrimali/

ebookmass.com

Factor Investing: From Traditional to Alternative Risk Premia Emmanuel Jurczenko (Editor)

https://ebookmass.com/product/factor-investing-from-traditional-toalternative-risk-premia-emmanuel-jurczenko-editor/

ebookmass.com

Governing the Rainforest: Sustainable Development Politics in the Brazilian Amazon Eve Z. Bratman

https://ebookmass.com/product/governing-the-rainforest-sustainabledevelopment-politics-in-the-brazilian-amazon-eve-z-bratman/

ebookmass.com

Relativity Principles and Theories from Galileo to Einstein Olivier Darrigol

https://ebookmass.com/product/relativity-principles-and-theories-fromgalileo-to-einstein-olivier-darrigol/

ebookmass.com

Mechanics of Flow-Induced Sound and Vibration Volume 2_ Complex Flow-Structure Interactions 2nd Edition William

K. Blake

https://ebookmass.com/product/mechanics-of-flow-induced-sound-andvibration-volume-2_-complex-flow-structure-interactions-2nd-editionwilliam-k-blake/

ebookmass.com

PredatorEcology PredatorEcology EvolutionaryEcologyofthe FunctionalResponse JohnP.DeLong

SchoolofBiologicalSciences,UniversityofNebraska-Lincoln andCedarPointBiologicalStation,USA

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford, OX26DP, UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries ©JohnP.DeLong2021

Themoralrightsoftheauthorhavebeenasserted FirstEditionpublishedin2021

Impression:1

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,withoutthe priorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rightsorganization.Enquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,atthe addressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress 198MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY10016,UnitedStatesofAmerica

BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData Dataavailable

LibraryofCongressControlNumber:2021937953

ISBN978–0–19–289550–9(hbk.)

ISBN978–0–19–289551–6(pbk.)

DOI:10.1093/oso/9780192895509.001.0001

Printedandboundby CPIGroup(UK)Ltd,Croydon,CR04YY

LinkstothirdpartywebsitesareprovidedbyOxfordingoodfaithand forinformationonly.Oxforddisclaimsanyresponsibilityforthematerials containedinanythirdpartywebsitereferencedinthiswork.

8.DetectingPreyPreferencesandPreySwitching

9.OriginoftheTypeIIIFunctionalResponse

Prologue Themotivationforthisbookwasthree-fold.First,Ipersonallywantedto learnmoreaboutfunctionalresponses.Ifound,however,thatinformation aboutfunctionalresponsesintheliteratureispiecemeal.Innoplacecould Ifindasynthesisaboutthem,despitetheexistenceofthousandsofpapers describingorparameterizingfunctionalresponsesforallmannerofpredators andprey.Second,therewasclearconflictintheliteratureaboutwhatmodels tousetodescribefunctionalresponses,thebiologicalmeaningofthemodel parameters,andwhyfunctionalresponsesvaryamongpredator–preypairs andacrossenvironmentalortrait-basedgradients.

Third,andperhapsmostimportantly,thefunctionalresponsebecamethe coreconceptformyfield-basedcoursecalled PredatorEcology.Iwantedto providemystudentswithanoverviewofthefundamentalsandthebiological relevanceoffunctionalresponses,sothatinshortordertheycouldinterpretpapers,conducttheirownexperiments,andgrasphownaturalselectionmightbeshapingpredator–preyinteractionsandthereforefoodwebs. Ineededtostartsynthesizingforthecourse,resolveconflictsinterminology andmodels,andhelpstudentsconnectthemathtothebiologicalrealityof nature.Thatwasthebirthofthisbook.

Soformeandanyoneelse,thisbookcoversthefundamentalsandthen offersadeepdiveintowhatfunctionalresponsesreallyare,howtothink aboutthem,whytheyarerelevanttoprettymuchanythingecological,and wherestudiesonfunctionalresponsesmightgointhefuture.Thisbookis whatIneededwhenIstartedteachingthePredatorEcologyclass.Thisbook isintendedforadvancedundergraduatestudentsandgraduatestudents,as wellasanyoneinterestedinfunctionalresponses.Thebookmovesbetween simpleintroductions,derivationsofthecoremodels,reinterpretationsand clarificationsoftheparametersandthefunctionsthemselves,andnovel hypothesesaboutfunctionalresponsesandtheirconsequences.Foranyone mostlyinterestedintheconceptsandbiologicalrelevance,itmaybeusefulto skipoversomeofthederivationsandfocusonthebiologicalmeaningoffunctionalresponsesandtheirparameters.Thencomebacktotheequationslater.

Tosupporthands-onlearningaswellasnewresearchintofunctional responses,thebookisaccompaniedbyafullsetofcodetoreproduceall dataandanalysis-basedfiguresinthebook.ThiscodeiswrittenforMatlab

©butcouldbetranslatedtootherscientificprogramminglanguages.The code,andassociateddataasnecessary,arehostedinazippedfolderat www.oup.com/companion/DeLongPE.Anycorrectionsorupdatestothe codewillbepostedatthissite.

Thisbookwouldnothavebeenpossiblewithoutthepatienceandsupport ofallthepeoplewhohavetakenandTA’dmyPredatorEcologyclassbothon CityCampusatTheUniversityofNebraska-LincolnandoutatCedarPoint BiologicalStation.Theirinvolvementhashelpedtokeepthemomentumon mypredatorecologyresearchgoing.Iappreciatethehelpfulcommentson draftsofthismanuscriptfromStellaUiterwaal,KyleCoblentz,andMark Novak.Icouldnothaveunderstoodtherootsumofsquaresexpression(see Chapter3)withoutthehelpofVanSavage.I’dliketogiveashout-outto HawkWatchInternational(www.hawkwatch.org),whereIgotmystartin predatorecologyshortlyaftercollege.Finally,noneofwhatIdowouldmake sensewithouttheloveandsupportofJess,Ben,andPearl,whomakemyheart soarlikeahawk.

Introduction Predatorsseemtobeuniversallyfascinating.Maybethatisbecausewe humansarepredators,orbecausewecanbepreyforotherpredators (Quammen,2004).Maybewearejustmorbidlycuriousaboutdeath. Whateverthereason,Ihavenoticedthatnatureshowstendtofocusalot onpredator–preyinteractions:thedramaofthepredator’shuntortherelief oftheprey’sescape.Wearedrawntopredationandintuitivelyunderstand thatitisafundamentalpartofnature.Indeed,whatapredatoreatsisoften amongthefirstthingsthatwelearnaboutit,suggestingthatwhoeatswhom isamongthemostcentralfeaturesofecologicalsystems,oratleastcentralto thewayweimaginethem(SihandChristensen,2001).

Predationisfundamentalbeyondtheeventofapredatorcapturingprey. Therateofpredationandtheidentityofthepreycombinetodirectthe flowofenergythroughecologicalcommunities.Asaresult,predationplays akeyroleinstructuringfoodwebs.Ofcourse,thereareotherwaysthat energyflowsthroughcommunitiesthatdonotinvolvepredation,suchas photosynthesis,herbivory,parasitism,decomposition,andtheconsumption ofdetritusornectar.Theseareallequallycrucial,butconsumingother organismsisawidespreadwayofgettingthatenergy,sounderstandingthe rateatwhichpredatorsconsumepreyisanecessarypartofunderstanding ecologicalsystems.

Sowhatcontrolstherateatwhichpredatorsconsumeprey?Manythings. Predatortraitslikeclaws,preydefenseslikecamouflage,habitatcomplexity, hunger,andthepresenceorbehaviorofotherpredatorsallplaytheirpart. Amongthesemanyinfluences,oneofthebiggestfactorsisthenumberofprey availabletobeconsumed.Generally,predatorshaveahigherforagingrate whentherearemorepreytobehad—uptoapoint.Therelationshipbetween foragingrateandpreyabundance(ordensity)isknownasthefunctional response(Holling,1959;Solomon,1949)(Figure1.1).

Thefunctionalresponseisadescriptionofhowmanypreyapredatorwould beexpectedtoeatgivenaparticularamountofpreyavailabletothepredator, wherevertheyaresearchingforfood.Thatexpectednumberdependson thebehaviorandmorphologyofbothpredatorandpreyinthecontextof

Prey consumed or foraging rate

No prey, no predation

Steep/high functional response

functional response

Prey abundance or density

Figure1.1. Somegeneralizedfunctionalresponses.Foragingratesmustbezerowhen preyareabsent,sofunctionalresponsesareanchoredattheorigin.Thecurves increaseaspreyincreases,buttheshapeofthatincrease,thepresenceofan asymptote,theoverallheight,andpossiblebendsinthecurvealldependonthe specificconditions,morphologies,andbehaviorsofthepredatorandpreyinvolved.

aparticularhabitat,sothefunctionalresponseisreallyanemergentproperty ofthetotalforagingprocess(Juliano,2001).Thefunctionalresponseisalways anchoredattheorigin—noprey,nopredation(Figure1.1).Therealsois alwayssomeincreaseinforagingrateaspreyincreases.Theshapeofthat increase,andbothanexplanationforanddescriptionofthatshape,depend onmanyfactors.Thesefactorsrelatetohowpredatorandpreymoveand encountereachother,howpredatorschoosewhattoattack,howgoodprey areatescaping,andwhatotherthingspredatorshavetodowiththeirtime besideshunting.

Functionalresponseshavealonghistoryinthescientificliterature(Jeschke etal.,2002).Ontheempiricalside,therearewellover2,000functional responsesmeasuredforhundredsofpredator–preypairs.Thesefunctional responseshavebeendigitizedandarchivedintherecentFoRAGEdatabase (FunctionalResponsesfromAroundtheGlobeinallEcosystems)(Uiterwaal etal.,2018).Thesemeasuredfunctionalresponsescovernumeroustaxafrom

Shallow/low

unicellularforagersofbacteriaandphytoplankton(Robertsetal.,2010)to wolves(Jostetal.,2005).Akeygoalofthisliteratureisunderstandingwhat determinestheshapeofthefunctionalresponseforanygivenpredator–prey interaction.

Onthemathematicalside,manymodelshavebeenproposedtodescribe functionalresponses(Akcakayaetal.,1995;Beddington,1975;Crowley andMartin,1989;DeAngelisetal.,1975;Denny,2014;Hasselland Varley,1969;Holling,1959;SkalskiandGilliam,2001;Tyutyunovetal., 2008;Vallinaetal.,2014).Withthesemodels,functionalresponseshavebeen usedtopredictpreyselection(Charnov,1976;Chesson,1983;Cock,1978) andinvokedasbuildingblocksofcommunityandfoodwebmodels(Boit etal.,2012;Broseetal.,2006;GuzmanandSrivastava,2019;Petchey etal.,2008;Ralletal.,2008;RojoandSalazar,2010).Thesedifferentforms offunctionalresponseshavebeenarguedoverandcomparedfortheir implicationsandconstruction(Abrams,1994;AbramsandGinzburg,2000; HouckandStrauss,1985;SkalskiandGilliam,2001).Yet,westilldonothave resolutionaboutwhatmathematicalexpressionsinfunctionalresponsesare mostuseful,mostbiologicallymeaningful,ormostgeneral.

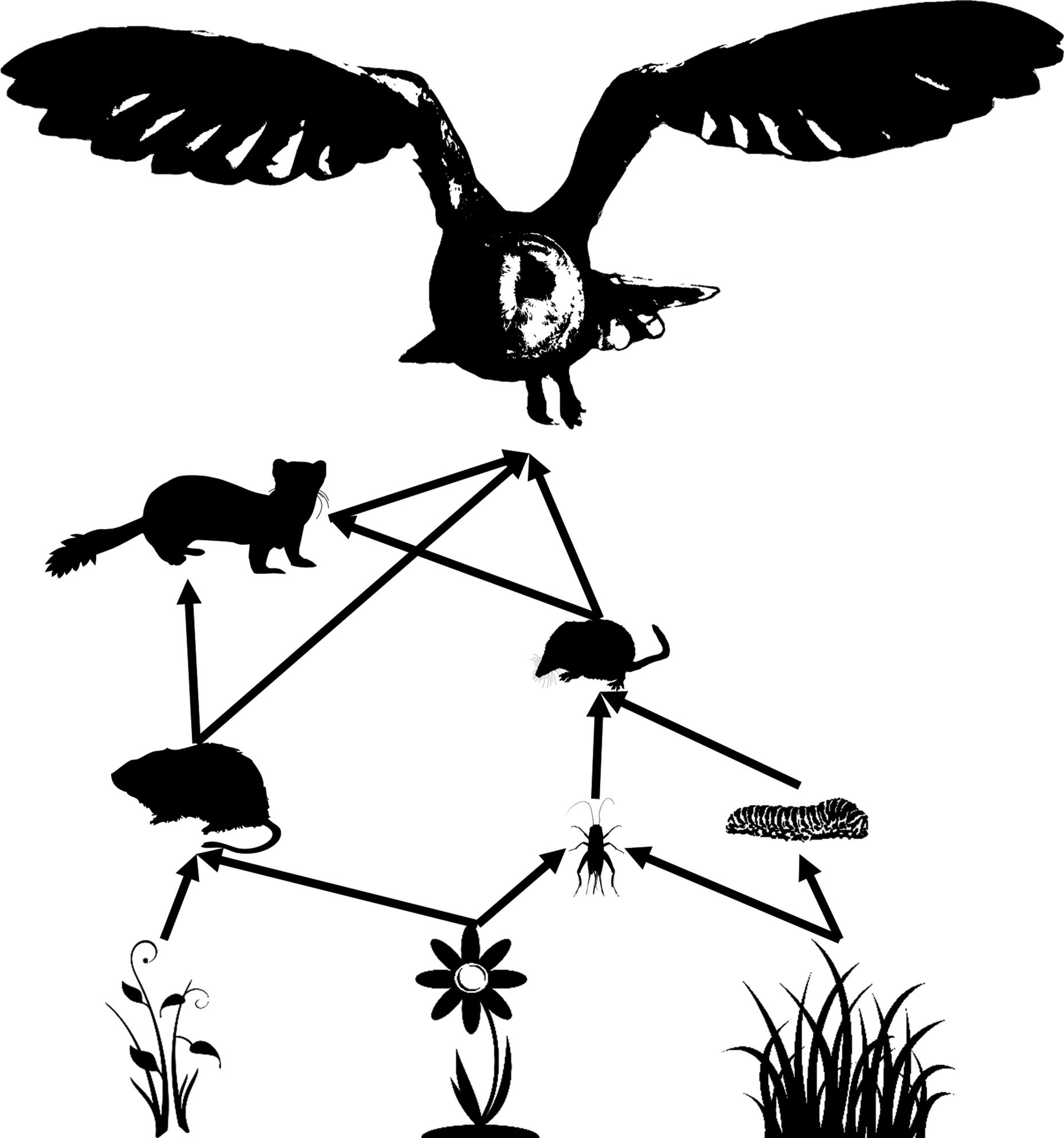

1.1Functionalresponsesandfoodwebs Evenwiththevastamountofworkalreadyconductedaboutfunctional responses,Iwouldarguethatwehaveonlyjustbeguntounderstandthe causesandconsequencesofquantitativevariationinfunctionalresponses. Thislimitedunderstandingistrueingeneral,butitiseventruerwhenit comestofunctionalresponsesastheyoccurinthefield.Ecologicalcommunitiescontainnumerousspeciesanduncountablenumbersofindividuals. Thenumberofpredator–preyinteractionsinevenarelativelysimplefood webcanrunintothehundreds.Inatypicalcartoonfoodweb(Figure1.2), justahandfulofspeciesleadstonumerouspairwiseforaginginteractions amongspecies.Ofcoursetherearefarmorespeciesinarealfoodwebthan showninthecartoon,andtheremaybeseparatefunctionalresponsesfor eachtypeofinsecteatenbytheshrewsorforeachtypeofgrasseatenby thecaterpillars.Wetypicallydrawsuchfeedinginteractionswithanarrow pointingtowardtheforager.Thus,herbivoresalsohavefunctionalresponses, asdoalltheinteractionsleadinguptothetoppredator,inthiscaseabarn owl(Tytoalba).Forthisreason,allofwhatfollowsinthisbookmayapply toorganismsconsumingplantsinpartorinwhole(e.g.,algivores)aswell asthecarnivorousmammalsthatoftencometomindwhenwethinkof

Figure1.2. Asimplifiedfoodweb.Functionalresponsescharacterizethe prey-dependentforagingrateforallpredatorsinthefoodwebincludingthe herbivores,notjustthetoppredators.Inthisway,functionalresponsessettherateof energyflowinfoodwebsfromplantstoapexpredators.

predators.Predatorsmayevenforageonbiologicalentitiesthatcausedisease, suchasvirusesandotherparasites(Andersonetal.,1978;Thieltgesetal., 2013;Welshetal.,2020),expandingtherelevanceoffunctionalresponse beyondthetypicalfoodchainsdescribedinecologytextbooks.Allofthese interactionscanbedescribedbyfunctionalresponses,andchancesarethey aremostlyquantitativelydifferentfromeachother(Jeschkeetal.,2002).They mayevenbequantitativelydifferentamongindividualpredatorswithina population(Hartleyetal.,2019;Schröderetal.,2016;Siddiquietal.,2015). Yet,tomyknowledge,therearenocaseswherethefunctionalresponsesof

alltheconnectedspeciesinafoodwebhavebeencharacterizedcompletely, althoughresearchershavedonemoretoestimatestrengthsofinteraction amongspeciesinfoodwebsinotherways(Gilbertetal.,2014;Woottonand Emmerson,2005).Thus,wemayhavelonglistsofpreytypesformanypredatorsinfoodwebs—whoeatswhom—butwegenerallydonotknowtherate ofpredationonmostifanyofthosepreytypes.Withoutthisinformation,we aretypicallyrestrictedtomakingtaxonomicorbodysize-basedassumptions abouttheshapeandheightoffunctionalresponsesinfoodwebmodels(Boit etal.,2012;Broseetal.,2006;DeLongetal.,2015;RojoandSalazar,2010; Schneideretal.,2012).

Becausefunctionalresponsesdeterminetheflowofenergyfromlowerto highertrophiclevels(Figure1.2),theystronglyinfluenceratesofbirthand deathandconsequentlythesizeofpredatorandpreypopulations.Variation intheshapeofafunctionalresponsethereforecanhavecrucialeffectsonthe dynamicsofpopulations.Forexample,asteepandhighfunctionalresponse (Figure1.1)meansalotofforagingandachancethatthepredatorcanoverexploittheprey,leadingtoinstabilityorpopulationcycles(seeChapter4). Thus,theshapeofthefunctionalresponseisimportant.Evenslightchanges tofunctionalresponsescanleadtobigchangesinthepopulationdynamics oftrophicallyinteractingspecies(Chapter4)(OatenandMurdoch,1975; WilliamsandMartinez,2004).Overall,itisthoughtthatfunctionalresponses shouldbeontheshallowsideinnature,meaningthatnoparticularpredator–preyinteractiondominatesalloftheenergyflow(McCannetal.,1998).Such “weak”interactionsminimizeoverconsumptionandencouragepersistenceof predatorandpreypopulations.WewillseeinChapter6,however,thatnatural selectionisnotlikelytofavorshallowfunctionalresponsesforpredators becauseshallowfunctionalresponseslimitenergyuptake.Understanding whatpullsfunctionalresponsesuporpushesthemdownisacentralproblem intheevolutionaryecologyofpredator–preyinteractionsandfoodwebs aswhole.

Becauseoftheireffectonpopulationdynamics,functionalresponsesplay aroleinvirtuallyalltypesofcommunitydynamics(HouckandStrauss,1985; RosenbaumandRall,2018),includingtrophiccascades(DeLongetal.,2015; LeviandWilmers,2012;RippleandBeschta,2012;Schneideretal.,2012), predator–preycycles(JostandArditi,2001;Korpimäkietal.,2004;Krebs etal.,2001;Oli,2003),andkeystonepredation(Paine,1966).Morethanthose dynamics,predationplaysaroleindeterminingthemagnitudeofecosystem functionsthatmanypreyorganismsconduct(Curtsdotteretal.,2019;Koltz etal.,2018;Wilmersetal.,2012).Predationisalsodependentontemperature (Burnsideetal.,2014;Delletal.,2014),andsotheimpactofclimatechange

onecologicalsystemswillinpartstemfromhowchangesintemperatureand precipitationalterthesteepnessandheightoffunctionalresponses(Binzer etal.,2012;Boukaletal.,2019;DeLongandLyon,2020).Indeed,itisclear thattemperatureitselfisamajordriveroftheshapeoffunctionalresponses (Daugaardetal.,2019;DeLongandLyon,2020;Englundetal.,2011;Islam etal.,2020;UiterwaalandDeLong,2020;Uszkoetal.,2017),indicatingthat functionalresponseswillplayakeyroleindeterminingtheeffectsofclimate changeonecologicalcommunities.

Thefunctionalresponsealsoplaysakeyroleinspeciesconservationand management.Forexample,introducedpredatorsaregenerallythoughtto havesteepandhighfunctionalresponsesintheirinvadedrange(Alexander etal.,2014).Thishighfunctionalresponsemayarisebecauseofamismatch betweentheoffensesofthenovelpredatorandthedefensesofthepotentially naïveprey,givingpredatorstheedgeinforaginginteractionsandachance tosurviveintheirnewcommunities.Withoutthatboostinforaging,out-ofplacepredatorsmightnotbeabletopersistandinvade,sincethefunctional responsecontrolstheenergyflowtothepredatorandthusitspopulation size.Thishypothesizedtendencymaybeonereasoninvasivepredators, whentheydoestablish,canbeparticularlydestructivetoawiderangeof prey(Dohertyetal.,2016).Similarly,biocontrolpredatorsarereleasedto controlthepopulationsofproblematicinsects,includingagriculturalpests andinfectiousdiseasevectors(Sahaetal.,2012;Tenhumberg,1995).Anideal biocontrolpredatorisonewithahighfunctionalresponseonthetargetpest, asashallowfunctionalresponseimplieslittlemortalityofthepest(Lam etal.,2021;Monaganetal.,2017).Indeed,wecanevenuseestimatesof thefunctionalresponsetoshowthatotherpestcontrolstrategiessuchas insecticidescanaltertheeffectivenessofthepredator(Buttetal.,2019). Similarly,thefunctionalresponseinfluenceshowwellmicrobialpredators andzooplanktoncancontroltoxicredtidesinmarinesystems(Jeongetal., 2003;KimandJeong,2004).Finally,humanscompetewithnon-human predatorsforpreysuchasgamebirds.Understandingthefunctionalresponse canbeacrucialpartofdevisingmanagementstrategiesfornativepredators thatmaintaintheavailabilityofharvestedpreyspecies(Smoutetal.,2010).In fisheries,thefunctionalresponseisneededforunderstandingandmanaging bothharvestedandunharvestedfishpopulations,asthefunctionalresponse influencestheabilityoffishpopulationstogrow(Hunsickeretal.,2011).

Thegenerallypositiveslopeoffunctionalresponsesalsosuggeststhatany behaviorsapredatorcanusethatcanincreasepreydensitycanincreaseforagingratesandthusindividualfitnessandpopulationgrowth.Forexample, northernshrikes(Laniusborealis)havebeenobservedsinginginwinter,with

theeffectofdrawinginpotentialpasserineprey,raisingpreydensityand thusforagingrates(Atkinson,1997).Smallforestfalconsalsomayusecalls forluringpreywiththesameeffect(Smith,1969).Inaddition,searching behaviorsornomadismwouldallowpredatorstoincreaseforagingratesby activelylocatingareas(localpatches)thatcontainmanyprey(Korpimäki andNorrdahl,1991).Thus,movementbehaviorcanallowpredatorstoalleviatetheconstraintofthefunctionalresponse,sometimesreferredtoasa “numerical”response,butthiswillnotbeafocusofthisbook.

Inshort,thefunctionalresponsedescribesanessentialprocessinecology, withramificationsfornearlyeveryaspectofnaturalsystemsandourability tomanagethemforecosystemservices,pestcontrol,orconservation.The remainderofthisbookthereforetakesadeepdiveintofunctionalresponses. Chapter2coversthemathematicalbasisoffunctionalresponses,showsthe derivationandmeaningofthestandardmodels,andstandardizesterminology.Chapter3describesknownvariationinfunctionalresponseswithin andacrossspecies.Chapter4showshowvariationinfunctionalresponses influencespopulationdynamics.Chapter5expandsthediscussiontomultispeciesfunctionalresponses,whicharethefunctionalresponsesofapredator feedingonmorethanonepreytype.Chapter6showswhyandhownatural selectionshouldactontraitsthatinfluencefunctionalresponseparameters. Chapter7describesoptimalforagingtheoryinlightoffunctionalresponses andhowwestilldonotunderstandforagingstrategies(optimalorotherwise) withrespecttofitness.Chapter8introducestheideaofpreyswitchingand showswhyfunctionalresponsesarenecessaryforunderstandingoreven identifyingpreypreferences.Chapter9discussesthemanypossibleoriginsof sigmoidalfunctionalresponses.Chapter10discussesthenatureoffunctional responsedataandreviewsstatisticalconcernsincurvefitting.Chapter11 suggestscriticalareasofresearchneededtounderstandmorefullyfunctional responsesandtheirconsequencesforecologicalcommunities.

TheBasicsandOriginofFunctional ResponseModels Thischapteristheessentialbeginner’sguidetothefunctionalresponse,its derivation,thevariousforms,itsconnectiontoothermodelsintheliterature, andwhattheparametersmean.Itisthegroundfloorfortherestofthebook. Surprisingly,ourunderstandingofthefunctionalresponseaspresentedin theliteratureisquitemuddled,withconfusionrangingfromtheterminology used,tothevariousmathematicalformsthefunctionalresponsetakes,tothe biologicalinterpretationoffunctionalresponsemodelparameters.Iprovide asummaryandforward-lookingperspectiveontheseissues.

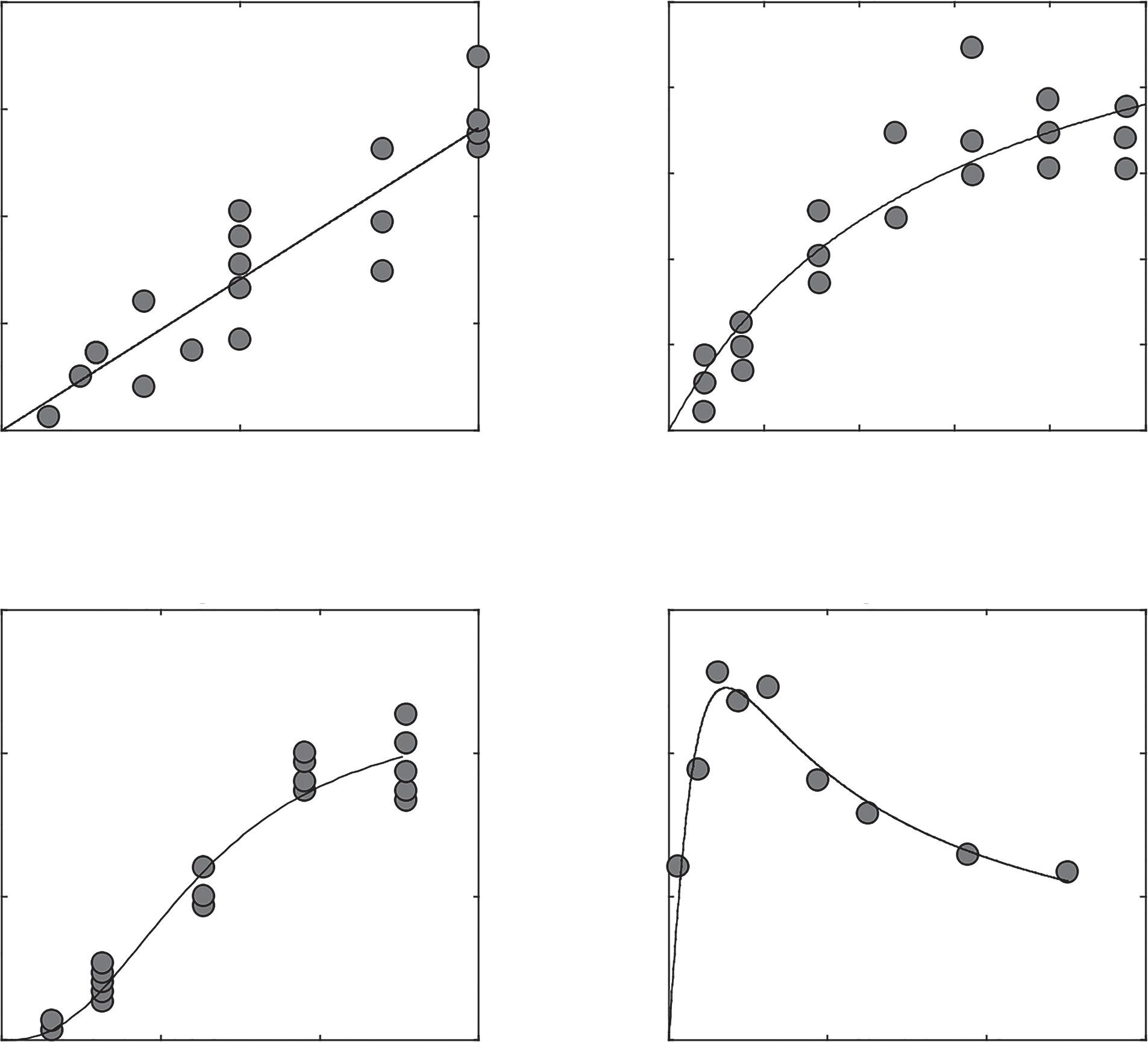

2.1Typesoffunctionalresponses Functionalresponsesarecurvesrelatingapredator’sforagingrateonaspecific preytotheavailabilityofthatprey(Denny,2014;Holling,1959,1965;Juliano, 2001;Solomon,1949)(Figure2.1).Theforagingratemustbezerowhenthere isnothingtoeat,sofunctionalresponsesareanchoredattheoriginandhavea positiveslopeatlowpreydensity.Aspreydensity1increasestohigherdensity, thefunctionalresponseusuallydoesoneofthreethings:itmaycontinueto riselinearly(thisiscalledatypeI,linearfunctionalresponse;Figure2.1A);it mayapproachanasymptote(typeII,saturatingfunctionalresponse;Figure 2.1B);oritmayincreaseveryslowlyatfirst,thenincreasemorequickly,and eventuallyapproachanasymptote(typeIII,sigmoidalfunctionalresponse; Figure2.1C).Althoughitmaybethatfunctionalresponsesshowmore variationthanthesethreetypes(Abrams,1982),andnumerousalternative formulationshavebeenderivedforvariouspurposes(Gentlemanetal.,2003; Jeschkeetal.,2002;Tyutyunovetal.,2008),thissimpleclassificationisstillin

1 Inthisbook,predatorandpreynumberswillbepresentedaseitherabundances(justanumberina space)orasdensity(anumberperspace).Althoughsometimestheyarepresentedinunitsofbiomass,it isimportanttorememberthatpredatorandpreyareindividualorganisms,andtheimpactofpredation onpopulationdynamicsandevolutionoccursthroughthegainorlossofindividuals.

Figure2.1 (A)AtypeIfunctionalresponseforthecombjelly(Mnemiopsisleidyi) consuminganchovies(Anchoamitchilli),fittoequation(2.1).DatafromMonteleone andDuguay(1988).ItispossiblethatthisfunctionalresponseistypeI,butitalsomay bejustincompletelydetermined.(B)AtypeIIfunctionalresponseforthecopepod Mesocyclopspehpeiensis foragingontherotifer Brachionusrubens,datafromSarma etal.(2013)andfittoequation(2.5).(C)AtypeIIIfunctionalresponsefortheladybird beetle Eriopisconnexa feedingontheaphid Macrosiphumeuphorbiae,datafrom Sarmentoetal.(2007)andfittoequation(2.7).(D)AtypeIVfunctionalresponseofthe spider(Zodarionrubidum)foragingonants(Tetramoriumcaespitum)andfitto equation(2.9).DatafromLíznarováandPekár(2013).

wideuseandcoversmuchofthegroundnecessarytounderstandfunctional responsesandwhattheyrepresent(Real,1977).Beyondthethreemain forms,somesuggestthatthereisalsoatypeIVfunctionalresponse(Figure 2.1D),withtheforagingratedroppingagainatveryhighpreydensity,but thisformhasnotbeendocumentedmanytimes(Baek,2010;Jeschkeetal., 2004).Althoughfunctionalresponsesalsoexistforherbivores(Andersenand Saether,1992),thisbookwillfocusonthefunctionalresponsesofpredators, thatis,consumersthatkilltheirprey,eveniftheyonlyeatpartoftheprey. Themainreasonformakingthischoiceisthatbynotkillingtheplant,an herbivorehasafundamentallydifferenteffectonthepopulationdynamics ofitsplantresources.Functionalresponsesalsoexistforparasitoidsthat

stunpreyandlayeggsintheirprey,butthesewillsimilarlybelessofa focushere.

Typically,weestimatetheshapeofafunctionalresponseexperimentally. Theusualapproachistomeasureforagingrateswithaseriesofforaging trialsinwhichanindividualpredatorforagesonsomearbitrarilyassigned numberofpreyforsomeprespecifiedamountoftime.Theresearcherthen countsthenumberofpreyremainingandassignsthedifferencebetweenthe preyofferedandthepreyremainingtopredation,tryingtoaccountforthe possibilitythatsomepreymayhavediedduringtheexperimentforreasons otherthanpredation.Then,thetypeoffunctionalresponsecanbedetermined byfittingamodeltothedatawithavarietyofmethods(seeChapter10).Here, amodelisjustanequationdescribingaprocessorpatternthatwebelieveto berelevanttoourdata—wewilllookatmanyoftheseshortly.Forexample,in Figure2.1IfitmodelsdescribingtypeI–IVfunctionalresponsestoeachdata set,andwecanseethat,withtherightparameters,theequationsdescribethe shapeofthedatareasonablywell.Wewillseelaterthatthereareotherways toestimateafunctionalresponsemodel,butthevastmajorityoffunctional responseshavebeenestimatedusingacurve-fittingapproach(Uiterwaal etal.,2018).Giventheimportanceoffittingfunctionalresponsemodels totheexperimentaldata,andtheimportanceofparameterizedfunctional responsesforpredictingpopulationdynamics(seeChapter4),itisimportant tounderstandwhatthemodelsare,wheretheycomefrom,andhowthey representasimplificationoftheforagingprocess.Thestartingpointhereis thetypeIfunctionalresponse.

The typeIfunctionalresponse arisesowingto(1)aforagingordefensivebehaviorthatdoesnotchangewithpreydensity,(2)apredator–prey encounterratebasedonrandomcontacts,and(3)thelackofatimecostfor thepredatorstodealwiththepreytheykill.ThetypeIfunctionalresponseis analogoustochemicalreactions,wheretherateofareactionisproportional totheproductoftheconcentrationofthereactants(i.e.,massaction).Not allofthereactionsthatcouldoccuramongreactantswilloccurwithina givenperiod,however,becausetheyaredistributedinspaceandittakes timeformoleculestocomeintocontact.Sothispotentialamountofreaction isscaledbyareactionrateconstant k.Therateofachemicalreaction, A,betweenreactant R1 andreactant R2 istherefore A=k[R1][R2],where thebracketsindicateconcentration.Forpredatorandprey,themassaction termistheproductofthepredatordensity [C,consumer;thinkcoyote] and thepreydensity [R,resource;thinkroadrunner],or [C][R].Massactionof predatorandpreyrepresentsliterallyallthepossibleencountersbetweeneach predatorinapopulationandeachpotentialpreyindividual.Aswithreactants,

predatorandpreyarespreadoutinspace,andittakestimeforthemtocome intocontact.Wethereforescalemassactionofpredatorandpreybysomerate constanta,whichhereIwillcallthespaceclearancerate(seeBox2.1),andadd timespentbythepredatorsearchingforprey Ts,togivethetotalamountof foragingas F = aCRTs,whereIhavedroppedthebracketsforsimplicity.In thetypeIfunctionalresponse,weassumethattheonlythingapredatordoes withitstimeissearchforfood,sothetotaltimeavailableforapredator(Ttot) isequaltoitssearchtime(Ts),whichmeansthatwecanupdateourequation to F = aCRTtot.Thefunctionalresponsedescribesthepercapita(i.e.,per individual)rateofforaging, f pc (inthisbookIwilluseasmall f forforaging rateandacapital F fornumberofpreyindividualsconsumed).Togettothe foragingrate,wedividebothsidesoftheequation F = aCRTtot by Ttot,and togettopercapita,wedividebothsidesoftheequationby C.Thesetwosteps yieldthetypeIfunctionalresponse:

Box2.1.Why a shouldbecalled“spaceclearancerate.” Thefunctionalresponseparameter a hasmanynames.Theterms attackefficiency, attackrate or successfulattackrate, attackconstant, rateofsuccessfulsearch, capturerate, maximumclearancerate, maximumpercapitainteractionstrength, instantaneousrateofdiscovery, rateofpotentialdetection,and instantaneoussearch rate haveallbeenusedasnamesforthisparameter.Thesenames,however,arenot gooddescriptionsofthebiologicalprocesscapturedbytheparameter,asisclearly evidentfromaunitanalysis.Theunitsoftheparameterare [space] [pred][time] .Wecansee thisbecausetheunitsofalineinthefunctionalresponsespacearetheunitsof therise ( [prey] [pred][time]) overtheunitsoftherun ([prey] [space]).Theseunitsclearlyindicatethat theparameterisnotarateofattack,whichwouldbe [attacks] [pred][time].Noristheparameter anefficiency,whichareoftenunitless,asinthefractionofenergyextractedfromthe energyavailableinafuel.Rather,bytheunits,theparameter a isthespace(areaor volume)containingpreythatiseffectivelyclearedofpreybythepredatorperunit oftime.Iformerlypreferredtheterm areaofcapture forthisparameter,asthisis closetotherealmeaningandhashistoricalprecedentinthe areaofdiscovery term previouslyusedforparasitoids(HassellandVarley,1969).Inthisbook,however,I advocateforrenamingthisparameterthe spaceclearancerate,whichiswhatthe unitssuggestisthebiologicalprocessbeingcaptured.

ItissometimesthoughtthatthetypeIfunctionalresponseincreaseslinearly andeventuallyreachesanabruptceiling(occasionallycalleda“rectilinear” shape),causedbythelimitsofgutcapacity,butthisceilingisrarelyobserved, difficulttodistinguishfromagradualasymptote,andgenerallyignoredin practice(Denny,2014;Fox,2013;Jeschkeetal.,2004).Jeschkeetal.(2004) suggestedthatinmanycaseswithoutanobservedceiling(e.g.,Monteleone andDuguay,1988),thefunctionalresponsealsocouldbeviewedasincompletelydeterminedandthereforecalleda“linear”functionalresponse.Only whenhigherpreyabundancesareusedwouldyouthenbeabletodetermine ifthefunctionalresponseincreasedlinearlytoaceilingorbegantotaperoff toanasymptote.

The typeIIfunctionalresponse isamodificationoftypeI,wherethe predatorpaysatimecost(calleda handlingtime)whenitcapturesprey.The handlingtimeincludesthetimeneededforsubduing,killing,consuming,and digestingpreyandthengettingaroundtosearchingformorefoodagain.This timeissubtractedfromthesearchingtimesuchthatthemorethepredator kills,thelesstimeitsearches.ThederivationofthetypeIIfunctionalresponse requiresbackingupastepfromequation(2.1)tothenumber ofpreycaptured percapita(big Fpc)insearchtime Ts:

ThetraditionalargumentinthederivationofthetypeIIfunctionalresponse isthatpredatorsmustdividetheirtimebetweensearchingforprey(Ts)and handlingprey(Th),sothetotaltimeis Ttot = Ts +Th.Thehandlingtimecost appliesonlyforpreyactuallykilled(Fpc),althoughitdoesinpracticeinclude thetimespentonunsuccessfulcapturespersuccessfulcapture.Therefore, thetotaltimebudgetcanbewrittenas Ttot = Ts + Fpch,where h isthe handlingtimeperprey.Since Fpc isalreadyspelledoutinequation(2.2),we cansubstitutethisintoourtimebudgettoget:

Thenwedividethetotalamountofpreycapturedbythetotaltime(equation (2.2)for Fpc dividedbyequation(2.3)for Ttot)andget:

Factoringout Ts ontheright-handsidegivesthestandardformofthetypeII functionalresponse:

ThetypeIIfunctionalresponseisalsocalledtheHollingdiscequation,after C.S.Holling,whousedstudentsforagingforsandpaperdiscstoillustratethe shapeoftheforagingcurve.ThetypeIIfunctionalresponseisthemostwidely usedfunctionalresponsemodel.

ThetypeIIfunctionalresponseisequivalenttothetypeIwhen h = 0. Processingprey,however,cannevertrulytakenotime—theremustalwaysbe sometimefordigestionormanagingprey—butthatprocessingtimemight notalwayscutintosearchtime.Asaresult,typeIfunctionalresponses existoveratleastsomepreydensities(Figure2.1A),eventhoughparticular examplesofthistypemaybejustincompletelydetermined.Thederivation ofthetypeIIfunctionalresponseassumesthathandlingtimeandsearching timearemutuallyexclusive;thatis,predatorscannotcontinuetosearchfor additionalpreywhiletheyarehandlingthepreytheyhavealreadycaptured. Thisturnsoutnottobecompletelytrueforallpredators.Forexample,afilterfeedingpredatormightcontinuerightonfilteringevenasitclearspreyfrom thewaterandstartsdigestingit,soitshandlingtimeiszeroanditsfunctional responseistypeI.

Thebestwaytothinkofthehandlingtimeisthelossofsearchingtime owingtohandlingprey,asonlywhensearchingisinterrupteddoesthe handlingtimecausethefunctionalresponsetosaturate,evenifhandlingand searchingarenotmutuallyexclusive.Thus,despitethenameoftheparameter, predatorsdonothavetobeactivelyhandlingpreytoincurhandlingtime, whereactivehandlinggenerallymeansthatthepredatorisstillmanipulating, biting,swallowing,orotherwisetryingtoingesttheprey.Theyonlyneed toexperiencealossofsearchingtime(Abrams,2000).Differentpredators mayexperiencelossesofsearchingtimeindifferentways.Forexample,some predatorsmaybeabletodigestpreviousmealswhilesearchingforthenext one,inwhichcasedigestionpersewouldnotbeacomponentofhandling time.Inotherpredators,suchassomesnakes,digestionmaybesocostlythat itcouldlimitadditionalsearching(Secor,2008).Asaresult,behavioralidentificationofhandlingtimeassomethingyoucanseethepredatorsdoingoften representsonlyaportionofthehandlingtimeasdefinedinthederivation ofthefunctionalresponse.Further,sincepredatorsarenot100%effective incapturingprey,anestimatedhandlingtimefromafunctionalresponse

experimentactuallymayincludeanamountoftimewastedonunsuccessful attackspersuccessfulattack(Jeschkeetal.,2002).Handlingpreythatare notcapturedsoundslikeaviolationoftheassumptions;however,itcanbe understoodthatthehandlingtimeforcapturedpreyincludessomeaverage numberoffailedattemptspercapturedprey.

Ifwedonotfactoroutthe Ts fromequation(2.4)aswedidearlier,we canwritethetypeIIfunctionalresponseinawaythatismorebiologically intuitive:

Equation(2.6)showsthatthetypeIIfunctionalresponseisjustthetypeI modelmultipliedbythefractionoftimeactuallyspentforaging ( Ts Ttot ).That is,ifapredatorspends50%ofitstimesearchingforpreyatsomepreylevel,the typeIIcurveatthatpreylevelwillbehalfthatpredictedbythetypeImodel.

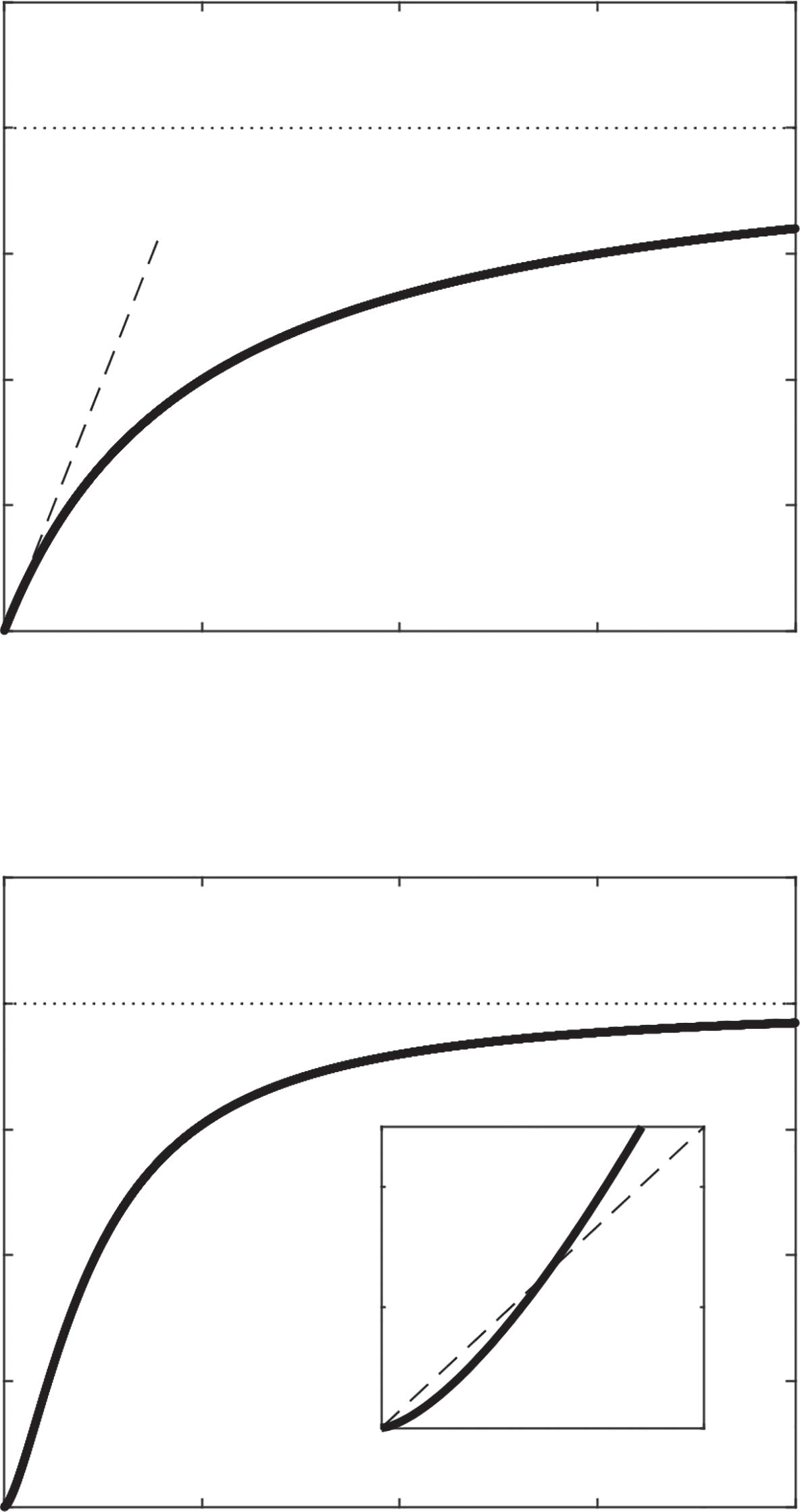

ThetypeIIfunctionalresponseapproachesamaximumforagingrateof 1/h (asymptoteinFigure2.2A).Thisshouldmakesense—apredatorcanonly consumeonepreyperhourifittakesanhourtohandletheprey.Thespace clearanceratecanbeseenonthefunctionalresponsecurveitselfastheslope ofthecurveas R → 0(Figure2.2A).Thishappensbecauseas R getsvery small,thedenominatorapproachesone,meaningthatthecurvecollapsesto approximatelytypeIveryneartheorigin,wheretheequationisjustthatofa linewithaslopeequaltothespaceclearancerate.

The typeIIIfunctionalresponse doesnot,tomyknowledge,haveamechanisticderivation.Onesimplyputsanexponent(suchas ��;oftencalledaHill exponent;Real,1977)onthepreyabundance, R��,transformingarisingand saturatingcurveintoonethathasasigmoidalshape(Figure2.2B):

ThetypeIIIfunctionalresponsemaybecausedwhenpredatorsavoida particularpreytypewhenitisrare,butchoosethatpreymoreoftenwhen itbecomesmorecommon.Thisprey-switchingexplanationisthemostcommonlyinvokedmechanismforgeneratingatypeIIIfunctionalresponse,butit isnottheonlypossibility(seeChapters8and9).Itisworthpointingoutthat thetypeIIIfunctionalresponseisoftendrawnasbendingupandreaching theasymptotemoreslowlythanatypeIIfunctionalresponse(Denny,2014). ThisisnottruewhenonesimplyaddsaHillexponenttoatypeIIfunctional

Figure2.2 Howtoseetheparametersspaceclearancerate(a)andhandlingtime(h)on afunctionalresponsecurve.(A)ForthetypeIIfunctionalresponse, a istheslopeofthe curveasitpassesthroughtheorigin,andthefunctionalresponseasymptotesat1/h (B)ForthetypeIIIfunctionalresponse,theasymptoteisthesameasinthetypeIIbut thespaceclearancerateisnoteasilyvisualizedalongthecurve.Theinsetshowsthat thecurverisesmoreshallowlythanatypeIIatfirstbutthensteepenstorisemore quickly.ThetypeIIIcurvealsoapproachestheasymptotemorequicklybecausethe effective a (aR��)islessthan a below R = 1andgreaterthan a above R = 1.

responsewhilekeepingthesamespaceclearancerate,inwhichcasethe typeIIIcurvecrossesthetypeIIcurveandactuallyapproachestheasymptote morequickly(Figure2.2B,inset).Itshouldgenerallybethecase,however, thatwhenestimatingafunctionalresponsefromdata,thespaceclearance ratewillbesmallerifatypeIIIcurveisusedasafittedmodelratherthana typeIIcurve(seeChapter9).

AswiththetypeIIfunctionalresponse,thesaturationpointonatypeIII functionalresponseis1/h (Figure2.2B).Thelocationofthespaceclearance rateonatypeIIIfunctionalresponseismuchhardertovisualizethanonthe typeII(seeChapter9).ItishelpfultorealizethattheHillexponentisreally justawaytomodify a suchthatpredatorsdonotclearmuchspacewhenthat specificpreytypeisrare.Thatis, a canbeafunctionof R (Juliano,2001).The typicalwaytodothisistorewrite a asanincreasingfunctionofpreydensity, suchas a = bRq,where q > 0andtheHillexponent ��= q + 1,andsubstitute thisintoequation(2.7):

Boththe �� (equation(2.7))and q (equation(2.8))versionsofthetype IIIfunctionalresponseareusedintheliterature(Smoutetal.,2010; Vucic-Pesticetal.,2010).

The typeIVfunctionalresponse isthecasewhenforagingratedeclinesat highdensities.Thatis,afterpreylevelshaveincreasedhighenoughforthe predatortoapproachtheasymptoticforagingrate,furtherincreasesinprey levelscausetheforagingratetodeclineagain(Figure2.1D).Thiseffectcould becausedbypredatorconfusioninthepresenceofalotofpreyorbythe risktothepredatorscausedbyanincreaseinthenumberofdangerousprey (JeschkeandTollrian,2005).Thistypeoffunctionalresponseappearsto bequiterare,andsomehaveevensuggestedthatitshouldbeviewedasa mathematicalartifact(MorozovandPetrovskii,2013).However,ithasbeen seenfortheodonatepredator Aeshnacyanea foragingonthecladoceran Daphniamagna (JeschkeandTollrian,2005)and Zodarion spidersforaging onavarietyofants,whichmayberelatedtothedangerantsposetotheir predatorsinlargergroups(LíznarováandPekár,2013).Onewaytomodel thiswouldbetoproposethathandlingtimeincreasesaspreylevelsincrease, perhapsbecausethehandlingchallengeismoredifficultwhenfacedwiththe riskincurredfromthepresenceofnumerousuneatenprey.Thus,wecould simplyaddanotherexponenttopreylevelsinthedenominatorofthetypeII functionalresponse:

AswiththeHillexponent,herethe g isjustaphenomenologicalparameter generatingaparticulareffectratherthananeasilyinterpretablebiological process.