The Challenge to the Global Trading System

Kent Jones

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Jones, Kent Albert, author.

Title: Populism and trade : The Challenge to the Global Trading System / Kent Jones. Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020045695 (print) | LCCN 2020045696 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190086350 (hardback) | ISBN 9780190086374 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Commercial policy | Protectionism. | International trade— Political aspects. | Populism—Economic aspects. | World Trade Organization. Classification: LCC HF 1411 .J624 2021 (print) | LCC HF 1411 (ebook) | DDC 382/.3—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020045695

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020045696

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190086350.001.0001

In memory of J. Michael Finger, 1939–2018 Trade Scholar, Visionary, Global Institutionalist

Contents

Preface and Acknowledgments

1. Trade and the Roots of Disaffection

The Essential Elements of Populism

Populism in Global and Historical Perspective

Organization of the Chapters

2. Trade as a Source of Populist Conflict

Attitudes Toward Trade: Behavioral Elements

Anthropological Origins

Politics and the Trade-versus-Protectionism Balance

The Politics of Populism

Sovereignty

Populism, Trade, and the Election Process

Behavioral Economic Models

Ideological Varieties of Populism

Populism and the Ideological Link to Trade

Summary

3. Emotional Flashpoints of Populism and Trade

Conceptual Flashpoints as Emotional Triggers

National Sovereignty

Deindustrialization and the Trade Deficit

Tariffs and Trade Bargaining as Weapons

Institutional Flashpoints as Objects of Derision

The WTO and Postwar Institutions of Global Trade

Regional Trade Integration Agreements

The European Commission as a Lightning Rod

Countries and Groups as Scapegoats

China and Mexico

Immigrants

International Terrorists

Summary

4. Populism, Trade, and Trump’s Path to Victory

US Populism in Historical Perspective

Jacksonian Populism

Know Nothings and Anti-Immigrant Sentiment

Agrarian Populism and William Jennings Bryan

The Great Depression and Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Response

Postwar Trade, the Globalization Crisis, and Renewed Populism

Growing Populist Anxieties

Trump’s Presidential Campaign

Changing Party Politics

Trump’s Anti-Trade Platform

Summary

5. Trump’s Assault on the Global Trading System

The First Assault: Trade Law Tariffs and Voluntary Export Restraints

Traditional Protection and Signs of Unilateralism

National Security Tariffs: Newly Interpreted as a Protectionist Tool

Voluntary Export Restraint: Anti-Competitive Quotas

The US-China Trade War

Section 301: Unlimited US Retaliation

The Phase One Agreement: Further Damage to the Trading System

Shutting Down the WTO Appellate Body

The Dispute Over WTO Dispute Settlement

Reactions to the US Appointments Veto and Possible

Solutions

Unilateralism, Discrimination, and a New Type of Trade Relations

The Proposed Reciprocal Trade Act

NAFTA and the Limits of Populist Leverage

Tariffs Threats as a Political Bargaining Chip

Summary

6. Brexit and the Crisis of European Integration

Introduction: The Roots of European Populism

Many Cultures and National Traditions in a Crowded

Geography

The Historical Context of Conflict Between the Elite and the People

Evolution of the European Union

Brexit

Trade as Collateral Damage from the Crisis

Prelude to the Referendum

The Brexit Vote

Early Aftermath and Estimated Economic Cost

Northern Ireland and Scotland

Taking Stock of Brexit’s Populist Impact

Populism and Trade in the Rest of the European Union

The Role of the Eurozone and Immigration Crises

The Lack of Trust in EU Institutions and Trade Policy

Prospects for Euro-Populist Protectionism

Summary

7. Populism and Trade Around the World

Populism and Trade Openness: An Empirical Study

The Data

Results of the Regressions

Assessing the Regression Results

Populist Regimes in Power

Latin America

The Middle East and Asia

Russia and Belarus

The European Union, Serbia, and Turkey

South Africa

Summary

Trade Freedom and Populism: Methodology

8. Assessing the Cost of Populism to Global Trade

Basic Economic Costs of Protection: Trump’s Tariff Policies

Welfare and Efficiency Costs

Reduced Product Variety, Rent-Seeking, and X-Inefficiency

Tallying the Welfare Cost of the Trump Tariffs

Globalizing the Tariff Cost to Foreign Consumers and Businesses

The Extended Web of Protectionist Impacts

Discrimination

Impact on International Supply Chains

Foreign Direct Investment and Immigration

Regional Trade Negotiations and the New USMCA

Brexit

The Cost of Institutional Erosion

The System’s Vulnerability

Currency Manipulation

The Cost of Eroding Domestic Institutions

The Wages of Trade War

Summary

9. The Future Belongs to Globalized Societies

Main Conclusions of the Book

The Populist Challenge

Trump’s Populist Manifesto

A Response to Unilateral Protectionism

Addressing the Roots of Populism Begins at Home

Rebuilding the Global Trading System

WTO Norms, Domestic Trade Law, and Unilateralism

Prospects for WTO Renewal

Final Thoughts

Notes

References

Index

Preface and Acknowledgments

This book sets out to examine the impact of populism on national trade policies and international trade institutions, such as the WTO and regional trade agreements. It will argue that the implementation of populist trade policies by the United States has not only increased the implementation of protectionist policies, but has also damaged the basic rules-based framework of the global trading system. The economic nationalism it has inspired has severely undermined the principles of nondiscrimination, multilateralism, and peaceful dispute settlement that had previously established a predictable and stable trading order. The book project began as a response to a disturbing —but ultimately not surprising—trend in the evolution of global trade institutions. As a student of trade policy in Geneva in the 1970s, in the shadow of GATT (later WTO) headquarters, I learned of the disastrous legacy of a chaotic world economy between the first two world wars, including beggar-thy-neighbor tariffs, crippling trade wars, and the Great Depression, with the world descending into World War II. In 1947 the victorious allied countries, led by the United States, established a new system of multilateral trade rules designed to avoid the self-destructive policies of the interwar period. For several decades thereafter, the world economy enjoyed unprecedented economic growth alongside multilateral trade liberalization and a remarkably robust adherence to GATT-WTO rules, with leadership from the United States and the European Union. Yet as my early mentor, Jan Tumlir, impressed upon me, global trade policy tends to follow a long wave of sequential learning and un-learning. The long period of trade liberalization, sparked by the lessons of the turbulent times that preceded it, appears now to have run its course. The biggest shocks to the trading system occurred in 2016, with two populist surprises. In June of that year, the United Kingdom voted in a referendum to leave the European Union, giving up its membership in an economic agreement that it

had joined in 1974 primarily for the trade benefits it offered. The Brexit vote represented a populist renunciation of a European trade and integration agreement that had begun in 1951 as a renunciation of war among former enemies, and served as the exemplar of successful international cooperation among its 28 member countries. The second shock came later that year, as Donald Trump, an avowed protectionist, won the US presidential election. In a few short years, the new populist US president began to dismantle the very global trading rules the United States had so strongly supported since 1947. His policies were not just protectionist; they were designed to overturn an entire system of global cooperation and return to an atavistic nationalist trade policy of mercantilism and unilateral tariffs. Understanding the origins of the global populist zeitgeist and its impact on trade policy is the goal of this book.

My acknowledgments begin with a tribute to my early mentors and influencers, now departed, who helped me to understand the nature and politics of trade and its global institutions: Jan Tumlir, Gerard Curzon, Robert Meagher, Rachel McCulloch, and J. Michael Finger, to whose memory this book is dedicated. More recently, I have benefitted greatly from observations and advice from Barry Eichengreen, Doug Irwin, Manfred Elsig, Gary Hufbauer, and especially Chad Bown, whose detailed and timely account of US trade policy in the Trump administration for the Peterson Institute has been particularly helpful in my research for this book. I am also grateful for critical reviews of earlier drafts of this book by my colleagues from various disciplines at Babson College, including Neal Harris, James Hoopes, and Martha Lanning, and by my sister, historian Jacqueline Jones of the University of Texas—Austin. I benefitted from additional helpful comments by participants in the International Trade and Finance Association Annual meeting in Livorno, Italy, in 2019, where I presented an early draft of parts of this book. My special thanks go to my colleague Yunwei Gai, whose help in preparation of the statistical study in chapter 6 was indispensable, and to my research assistant, Anna Saltykova, for help in the preparation of several tables and the bibliography. As always, I am eternally thankful for my wife, Tonya Price, whose

patience and support served as essential inputs in completing this book.

1

Trade and the Roots of Disaffection

In the global trading system, the age of anxiety has given way to the age of populism. Since the financial crisis of 2008, voting for populist candidates in many countries has grown, and in recent years surged to levels not seen since the 1930s. Beginning in 2018, the United States imposed tariffs and other trade restrictions on a number of products and even initiated a trade war with China, echoing the tariff wars of the 1930s. Trade tensions have escalated to major confrontations among countries, even among long-standing allies. For the first time since the end of World War II, trade actions began to ignore the rules established by global trade agreements. In the United Kingdom the populist Brexit movement delivered a further blow to the trading system, setting in motion a reduction in trade and investment integration in Europe. Populist governments in many other parts of the world have had varying impacts on trade policy, depending on economic and political factors specific to the country. But in general, the populist-induced erosion of the rules of the game has already imposed economic costs on businesses and consumers around the world, through disruptions in consumer market and supply-chain linkages. Retaliatory tariff measures in response to the defiance of World Trade Organization (WTO) rules and norms have deepened the crisis. Reduced investment in trade-related businesses has dampened trade flows even more and amplified damage to the world economy A continuation of such policies will compound the problem by imposing higher costs on businesses and consumers, and it could split the world into competing defensive trading blocs and cripple global economic growth.

Table 1.1 US-Initiated Trade Restrictions and Retaliation, January 2018–January 2020

Date Initiated by Against Action Products

2018

Jan. 22 US Korea Section 201 (safeguard) Washing machines

China Solar Panels

Mar. 23 US Most countries Section 232 (nat’l security tariffs) Steel

Most countries Aluminum

Mar. 28 US Korea Section 232 VERs* Steel

Apr 2 China US Retaliation Steel/Alum tariffs

June 1 EU, Canada, Mexico Extend Section 232 Steel/Alum

June 22 EU US Retaliation Food, consumer goods

July 1 Canada US Retaliation Steel/aluminum, Food, consumer goods

July 8 US China Section 301 trade war tariffs I Various goods

China US Trade war tariffs I Various goods, food

Aug 10 US Turkey Doubled tariffs (for currency manipulation) Steel/aluminum

Aug. 14 Turkey US Retaliation Cars, alcohol, tobacco

Aug 23 US China Trade war tariffs II Various

Aug. 23 China US Trade war tariffs II Various

Sept 24 US China Trade war tariffs III Various

Sept. 24 China US Trade war tariffs III Various

Aug. 27 US Mexico, Canada USMCA** VERs*, wage provisions Autos

2019

May 10 US China Raise tariff III rates Various

May US Mexico Tariff quid pro quo Immigration policy

June 1 China US Retaliation: higher tariff III rates Various

June 5 US India Withdraw GSP benefits All Indian exports

June 15 India US Retaliation Steel/alum

2020

Jan 15 US, China Phase One trade war truce Various trade quotas

Jan. 24 US Several countries Section 232 extension Steel/aluminum derived products

* VER: voluntary export restraint, prohibited by WTO rules.

** USMCA: United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, successor to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)

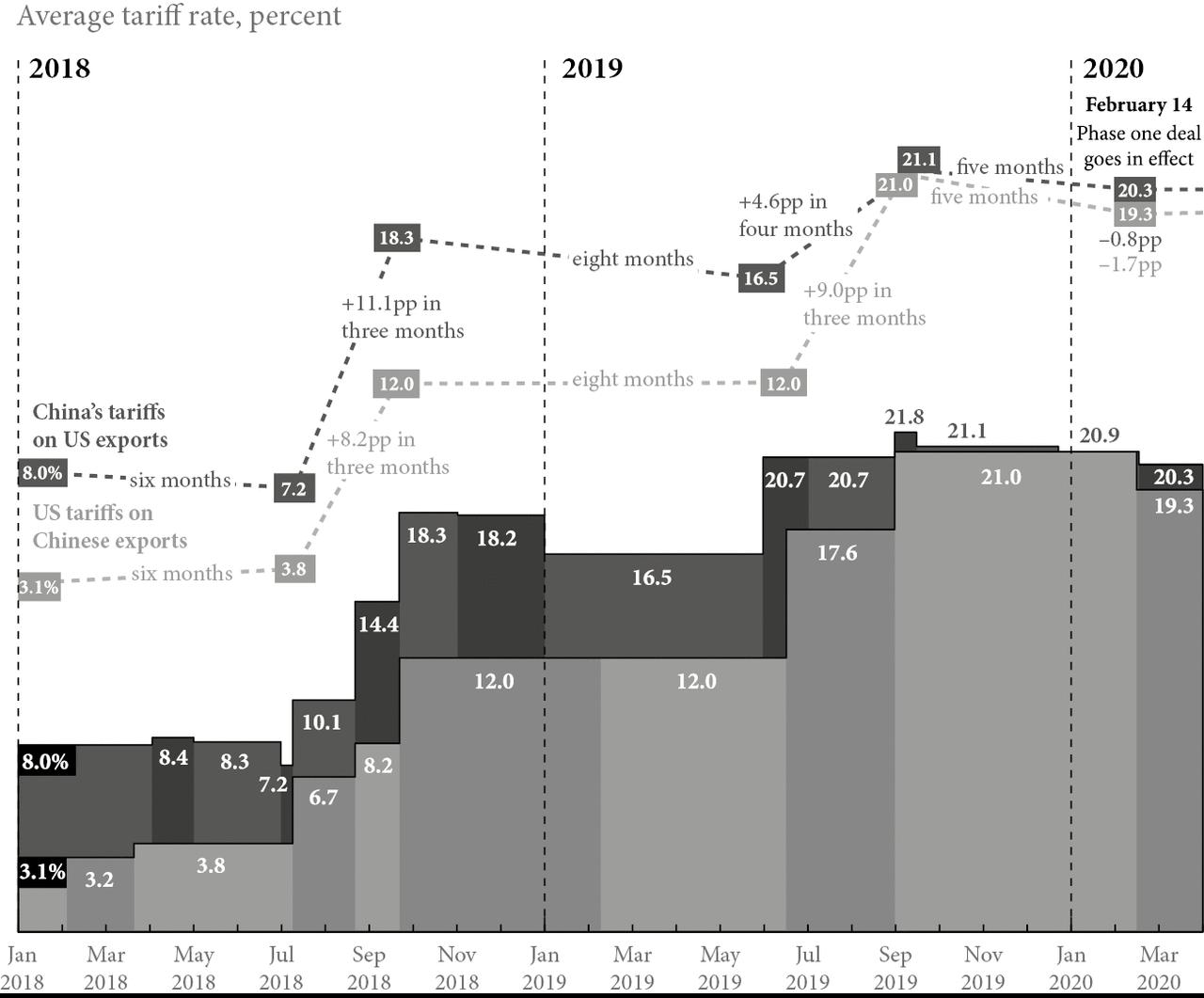

Figure 1.1 US–China Trade War: Escalation of Tariffs, January 2018–March 2020

Source: Bown (2020a).

Table 1.1 lists the trade restrictions imposed by the Trump administration, along with the retaliatory actions they provoked, from January 2018 to January 2020. Figure 1.1 focuses on the escalation of tariffs that took place in the US-China trade war through early 2020. Nearly all of the trade restrictions, including the foreign retaliation, defied WTO rules or long-standing practices. Thus Trump’s unilateral protectionist measures, such as national security tariffs and the US-China trade war, not only attacked the trading system, but incited US trading partners to violate these disciplines as well. Together the exchange of tariffs represented a major erosion of the WTO as an institution. Other actions, targeting smaller countries,

were overt violations of specific WTO provisions. The negotiation of a voluntary export restraint (VER) agreement with the Republic of Korea on steel violated the WTO safeguards provision prohibiting such measures. The use of threatened tariffs against Mexico to change its immigration policy violated the tariff binding provision of General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) Article 2, not to mention the regional North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) provisions on market access between Mexico and the United States that existed at the time. The US-China Phase One agreement represented another major derogation of WTO rules and practices, establishing a discriminatory system of US export quotas to China. The list does not include other US assaults on WTO institutions, such as the veto of dispute settlement appellate body judges, to the point where panel decisions in dispute cases no longer had access to appellate review, crippling the entire system. These are some of the ways that populism is undermining the global trading system.

The Essential Elements of Populism

What is populism? Studies of this topic span the disciplines of sociology, psychology, political science, and economics.1 The most widely accepted definition is that populism is a national political movement in democratic societies that presents a country’s critical issues in terms of a conflict between two diametrically opposed groups: the “people” and the “elite.” The most extreme versions of populism see the country as facing a Manichaean confrontation between the forces of good (the people) and the forces of evil (the elite). The people are genuine, hard-working, authentic but disaffected citizens, who must contend with a dishonest, aloof, exploitative, ruling elite aligned with larger, nefarious (and often foreign) economic and cultural influences. The populist scenario generally presumes a current elitist regime in control of political and economic institutions that the people must replace with a populist government. An important element of populism is that traditional political parties are either inadequate in representing the genuine people, or are conspiring with the elite. Thus a populist movement, operating outside mainstream political parties, presents itself as the

only political entity that can give proper voice to the people. A charismatic populist leader usually emerges to channel the group’s anger and maintain momentum to achieve political power. A successful populist movement then typically establishes itself as an insurgent force that overturns the status quo. Only then can the people create or restore their legitimate rights and benefits. The most distinctive feature of populism as a form of politics is therefore its polarizing nature. For supporters of a populist movement the status quo is not only unfair, it is outrageous, unnatural, despicable—an unjust situation that requires root-and-branch removal of existing policies and institutions. In most if not all cases, a charismatic leader heads a successful populist movement, winning support through resonating salt-of-the-earth rhetoric and “tough talk” against the elite, and focusing populist anger with slogans and anti-establishment policy goals. Yet even after a populist government comes into power, the basic conflict remains its animating force.

After President Trump’s 2016 victory, former US President Barack Obama asked with some wonderment why Trump’s supporters continued to be so angry—after all, they had won the election. But the reason lay in the nature of populism itself, which is essentially an expression of the perpetual politics of anger. The anger can have various roots, motivated by various sources of disaffection. It can come from humiliation when jobs are lost, dependency on government welfare increases, and retirement savings evaporate prematurely. It can come from the fear of losing one’s job in the future, due to imports, technology, or other forces beyond a worker’s control, based on current trends and the fact that one’s neighbors have lost their jobs. Anger intensifies when the forces can be identified: politicians who support trade agreements that cause job losses, a multinational firm that relocates its factory to China, and EU directives from Brussels that dictate policies in the United Kingdom. Anger may grow when elites in the population are seen to be thriving, while the hapless people are left behind. City elites may often be pitted against country folk. Anger can well up among individuals, indirectly caused by havoc that disruptive market or social forces impose on the broader community and region, including poverty, drug abuse, and suicide. In this regard, a perceived demographic threat of

immigrants and their unfamiliar cultures, languages, and religions may also instill anger based on resentment of the changing face of a neighborhood, and fear of displacement harbored by established native ethnic and cultural groups. Sociologists refer to this anger as a response to “status deprivation.” Fears of crime and even terrorism can heighten anti-immigrant backlash. Restrictions on gun ownership may become a rallying cry against those who would deny the people’s right to self-protection. The enemy within may be seen as those who undermine traditional social and religious mores: proponents of abortion rights, gay marriage, and gender equality. A successful populist movement typically emanates from a feedstock of mutually reinforcing discontents, which a populist leader can transform into potent, visceral anger focused on a culpable elite. A populist government sustains its political fortunes largely by stoking continuous angry energy needed among supporters in order to win the next election. In order to understand voting patterns and behavior under these circumstances, one must account for the role of emotions in the polling booth, where elections are transformed into life-and-death decisions on cultural and economic survival.

A key question surrounding populism is whether it is ultimately beneficial or detrimental to a country. This book will take up the question in terms of trade policy and its institutions. In principle, populism represents a political process, rather than an ideological set of policy prescriptions, although populist movements often adopt ideological frameworks to shape their political strategies. As a response to inadequate political representation, a major populist movement reveals a valid concern in democracies: the lack of political channels for a large portion of the population to express their grievances in a deliberative, pluralistic forum. Disaffected voters regard major political parties, or the controlling factions within them, as unresponsive to their concerns. In this regard, populism is the neglected—and resentful—stepchild of democracy. Populist movements seek to redress the perceived injustices and misdeeds of an untrustworthy regime and to implement needed changes. On this point also, governments facing such resentment must consider what caused the populist movement to arise, and how it might have been avoided. Newly enfranchised supporters of US President Andrew

Jackson in the 1820s and 1830s, for example, demanded replacement of land-holding elites who occupied most high government positions at the time and had allegedly favored elite interests in their policies. US populist movements in the Great Depression era of the 1930s demanded economic reforms, leading to the New Deal policies that still define many regulations and social safety nets in the United States today These examples show that individual attitudes toward populism depend heavily on one’s perspective. Many economic and political activists of the twenty-first century, for example, supported Occupy Wall Street and antiglobalization movements in order to overturn what they saw as an unjust, inequitable, political and economic power structure. On the other hand, many established ethnic, religious, racial, and cultural groups support nativist populist movements. They do so because these movements promise to protect or restore their dominant status, and also to restrict the intrusion or role of foreign or unfamiliar people or influences on society.

This book will approach the question of populism’s impact with two criteria in mind, based on the fruits of a populist regime: how a populist government affects economic welfare for a country’s entire population, and how it treats democratic institutions. Populist governments may implement short-sighted economic policies, designed to please their populist base but which instead lead to damaging inflation, significant trade welfare losses, market collapse, capital flight, price-gauging market concentration of industries, and corruption. Such policies are detrimental, regardless of the regime’s original motivation to redress an unjust situation. Populist governments that implement lasting reforms, achieving support among the broader population beyond their term in office, are correspondingly beneficial, in terms of revealed preferences of the entire pluralistic society Liberal democracy plays a crucial role in this assessment. The greatest danger of populism comes from the potentially perverse political dynamic it may create. Since by definition it is (or starts as) a democratic phenomenon, a populist government is subject to new elections. Populist leaders, having ridden a wave of anger into office, face the temptation of perpetually demonizing the elite, thus continuing the polarization of society,

factionalizing government, and destroying the capacity for political deliberation and compromise. What is worse, populist leaders, fearing political opposition to their policies, may begin to dismantle democratic institutions in order to avoid giving up their office. Erosion of democratic institutions has occurred in many populist governments, through restrictions on freedom of the press and speech, seizure of the power of the judiciary, marginalization of the elected legislature, and the elimination of constitutional checks and balances. Studies of populism and democratic institutions show that all types of populist government tend to diminish democratic institutions, the longer they remain in power 2 Populism exists on a political continuum; it ranges from governmental systems with wellestablished democratic traditions and institutions and protections for minority groups and opposing political parties, to authoritarian rule that concentrates power in a single ruler or party, with progressively weaker democratic traditions and legal protections for groups outside the populist base diminishing to zero. The starting position on the continuum for a new populist government in power is how well developed a country’s democratic institutions are when a populist government wins the election. More critical is what happens during subsequent election cycles. The implications of this result are that strong and robust democratic institutions are required, with continued active support of the population, in order to discipline the temptation of authoritarianism that populist governments face. Both the economic welfare and the democratic criteria used in judging populism are reflected in the government’s trade policy, through its impact on the population and on the institutional processes of its formulation and implementation. At the same time, the impact of an economically incompetent and anti-democratic populist regime will wreak havoc that goes well beyond the effects of its trade policy. The individual characteristics and ambitions of a populist leader play a crucial role in the policy outcomes for a country.

Populism in Global and Historical Perspective

Populism is a global phenomenon, even as it varies among countries according to their individual historical, cultural, and political

environments. In addition to the United States and the United Kingdom, there were at least 23 other governments around the world with populist governments of various types in the years 2017–2021. In Eastern Europe, long-standing populist regimes in Russia and Belarus began under conditions of weak democracy, which have become more authoritarian. Serbia’s government is also populist, but aspires to membership in the European Union, which tends to encourage softer, less confrontational, domestic and foreign policies. In the European Union itself, the populist government in the UK had the greatest impact, negotiating its final EU withdrawal by late 2020. However, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, and Poland also had populist governments, defined since 2015 in part by immigration restrictions and cultural issues. Greece briefly had a leftwing populist government in the wake of its financial crisis, while Italy had several populist governments from the mid-1990s until 2019. Populist parties in that country remained strong in early 2021, also motivated by immigration and refugee concerns. In addition, populist parties throughout Europe garnered increasing shares of electoral votes from 2014 through early 2020, receiving approximately 25% of all votes in national parliamentary elections during this period. Norris and Inglehart (2019) tallied 135 active populist parties in European countries in 2014. In the Middle East, Turkey has a long-standing populist regime of authoritarian character, while Israel has its own brand of populism, defined by the Palestinian issue and regional hostilities. In Africa, the country of South Africa has had left-wing populist governments in recent years, fueled by land reform, failed stagnating economic development, and income distribution issues. Populism also plays a prominent role in Latin American countries. Venezuela remained technically populist in early 2021, although it had by that time become a failed state with highly eroded democratic institutions. Brazil and Mexico had recently elected populist governments in 2021, neighbors of a long-standing populist regime in Nicaragua. The populist government in Bolivia was deposed in 2019, but its future remained uncertain. Argentina’s newly elected government in 2019 was Peronist, with historically populist roots, but the nature of the new regime was not yet clear. In Asia, India’s populist government focused on ethnic and cultural divisions, and Sri

Lanka’s populist governments have been driven by outright civil warfare between ethnic populations. Indonesia’s populist regime, on the other hand, was attempting to keep such divisions from boiling over. Populism in the Philippines in 2021 was strongly authoritarian. Among these populist governments, trade policies have varied according to the context of each country’s “elite versus people” conflict and the role of trade in each economy

Since populism as a political phenomenon is linked in principle to democratic electoral processes, populist movements can be traced back to the nineteenth century, with the ascendency of representative democratic systems of government (Eichengreen 2018). This definition excludes revolutions, coups d’états, and other violent or furtive means of overthrowing a government, even though such events may have popular support. Thus the French and Russian Revolutions of 1789 and 1917, respectively, may have involved popular insurrections but were not populist movements as such, since they occurred outside the realm of democratic politics. In this regard, countries such as Venezuela and the Russian Federation represent borderline cases of populism in the early twenty-first century. Their populist leaders—Hugo Chavez and later Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela, and Vladimir Putin in Russia—attained power initially through democratic elections, although democratic institutions may have been shallow or weak at the time. These administrations subsequently dismantled democratic institutions and gained control of the political process, to the point where it became extremely difficult for opposition candidates to gain power or even representation in the populist-dominated government. Yet a veneer of democratic elections appears to be part of an advanced populist regime’s claim to political legitimacy, all the more so in order to reinforce its claim of representing the people.

Populism spiked dramatically in the two decades following the end of World War I in 1918. These were years of political and economic turmoil: many war-weary populations lost trust in their governments, empires fell or sank into decline, power relationships were realigned, new technologies disrupted the workplace and society, and the global economy descended into the Great Depression (Funke et al. 2016). The result was a corresponding rise in political extremism, a

cautionary tale for the twenty-first century. While fascist, communist, and other authoritarian dictatorships during this period differed in principle from populist regimes, they sprang from similar political conditions. For example, Hitler’s path to power in Germany went through the electoral process, as his National-Socialist party achieved a plurality in the 1932 German elections, after which Kaiser Wilhelm appointed him Chancellor At this point, the Hitler government technically qualified as populist, despite lacking a parliamentary majority. Yet Hitler soon proceeded to claim emergency powers after his supporters allegedly staged the Reichstag fire. He then eliminated political rivals, decertified all parties other than his own, and eventually gained control over all domestic political, civil, and social institutions. Free elections did not return to (West) Germany until 1949, and during Hitler’s rule, Nazi Germany was a fascist dictatorship. Other fascist dictatorships also took power in post–World War I Europe: Italy under Mussolini in 1922, and Spain under Franco in 1939. These dictators also once headed populist political parties, but without electoral success, and gained power through military means. This was also true in Japan, where a military dictatorship displaced weak democratic institutions through intimidation, aggressive foreign incursions, and assassination.

After World War II, populism receded as a major political force in most Western countries. Postwar recovery and reconstruction reinvigorated democracies, and robust economic growth and international trade helped maintain political peace at home and abroad. The Cold War conflict between the United States and Soviet Russia also helped to channel anxieties away from populist issues. This trend provides food for thought in understanding the environment in which populism can grow. Economic growth eventually slowed in most Western countries by the 1980s, as their economies matured and as developing countries began to compete in world trade. On top of disruptive trade and technological change, a powerful shock occurred with the global financial crisis of 2008, leaving a new populist surge in its wake. As we entered the third decade of the twenty-first century, many populist movements came to regard elites as the champions of globalization and of the multilateralism that grew out of postwar cooperation, integrating trade

and financial flows among neighboring countries and around the world. Populist groups targeted elites as their tormentors across a variety of dimensions. In many countries, openness to trade has come with openness to foreign workers, immigrants, and even refugees. Diversity in racial and ethnic backgrounds then came with diversity in traditions and at times a collision of these traditions, which were often unfamiliar or strange to each other Supporters of this type of populism tied their anger against the elite to diminished cultural, racial, social, or economic status. The populist agenda therefore combined various types of discontents into a larger platform for removing the incumbent elitist government. International trade may or may not have been a major part of the platform, but “globalist” trade policies remained an easy target of populist ire in that they could be linked to disruptions in the economy, especially in areas of diminished industrial output and employment. As the following pages will show, populism is by its very nature anti-establishment; once it undermines a trade regime with protectionist measures, domestic and global institutions of trade may weaken.

Organization of the Chapters

The rest of the book is organized as follows. Chapter 2 provides a conceptual framework for the link between trade and populism, based on anthropological and sociological research, examination of populist voting behavior, and current ideological profiles of populist movements. Chapter 3 describes the flashpoints of trade and populism: the hot-button topics and slogans of populist rallies, including national sovereignty, deindustrialization, trade deficits, tariffs, trade bargaining, China, the World Trade Organization, the European Commission, and immigration. Chapter 4 traces the development of populism in the United States, from Jacksonian populism in the first part of the nineteenth century to the post–financial crisis years of the early twenty-first century, including Donald Trump’s successful presidential campaign. Chapter 5 explores the central issue of President Trump’s populist assault on global trading rules and the pattern of protectionist policies he implemented during his presidency, culminating in the US-China trade war. Chapter 6

turns to Brexit and the populist surge in Europe, a reaction to centralized decisions by the European Council, Eurozone officials, and the European Commission regarding immigration, monetary integration, and regulations. While trade was not the main reason for Brexit, its trade implications will be of great importance for the postBrexit United Kingdom, and perhaps for trade policy in the European Union in the future. Chapter 7 begins with a statistical study to determine if populist governments tend systematically to be protectionist, and then briefly profiles current and recent populist governments around the world in terms of their trade policies. The final two chapters assess the cost of populism and the outlook for addressing the root causes of populism. Chapter 8 summarizes economic research on the welfare cost of populist trade restrictions and the damage populism has inflicted on trade institutions, focusing on Trump’s trade policies, the foreign retaliation they sparked, and the impact on the global system of trade policy rules. The final chapter presents the main conclusions of the book and discusses domestic economic policies to address underlying causes of the populist backlash against trade. It also addresses possible reforms at the World Trade Organization, and alternative ways to mend the fractures in multilateral trade cooperation that are likely to outlast the populist surge of the early twenty-first century.