Politicizing Islam in Central Asia

From the Russian Revolution to the Afghan and Syrian Jihads

KATHLEEN COLLINS

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 978–0–19–768507–5 (pbk.)

ISBN 978–0–19–768506–8 (hbk.)

ISBN 978–0–19–768508–2 (epub.)

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197685068.001.0001

Formychildren,Michael,Katie,andElisa, Mayyoualwaysbeblessedwithfreedom,peace,andlove

Contents

ListofFigure

ListofImages

ListofTables

ListofMaps

Acknowledgments

TechnicalNote

ListofAcronyms

PART I: UNDERSTANDING ISLAMISM

Introduction: An Overview of Islamism in Central Asia

1: Secular Authoritarianism, Ideology, and Islamist Mobilization

PART II: THE USSR POLITICIZES ISLAM

2: The Russian Revolution and Muslim Mobilization

3: The Atheist State: Repressing and Politicizing Islam

4: Muslim Belief and Everyday Resistance

PART III: TAJIKISTAN: FROM MODERATE ISLAMISTS TO MUSLIM DE MOCRATS

5: The Islamic Revival Party Challenges Communism

6: A Democratic Islamic Party Confronts an Extremist Secular Stat e

7: Society and Islamist Ideas in Tajikistan

PART IV: UZBEKISTAN: FROM SALAFISTS TO SALAFI JIHADISTS

8: Seeking Justice and Purity: Islamists against Communism and Karimov

9: Making Extremists: The Uzbek Jihad Moves to Afghanistan

10: Society and Islamist Ideas in Uzbekistan

PART V: KYRGYZSTAN: CIVIL ISLAM AND EMERGENT ISLAMISTS

11: Religious Liberalization and Civil Islam in Kyrgyzstan

12: Emergent Islamism in Kyrgyzstan

13: Society and Islamist Ideas in Kyrgyzstan

PART VI: FROM CENTRAL ASIA TO SYRIA: TRANSNATIONAL SALAFI JIHADISTS

14: Central Asians Join the Syrian Jihad

15: From Central Asia to Afghanistan, Syria, and Beyond

Appendix:QualitativeResearchMethodandSources Glossary Index

List of Figure

1.1:

The process of Islamist emergence and mobilization

List of Images

3.1: 6.1: 6.2: 6.3: 6.4: 6.5: 8.1: 8.2: 8.3: 9.1: 9.2: 9.3: 11.1: 11.2: 12.1: 14.1: 14.2: 14.3: 14.4: 14.5: 14.6: 14.7: 14.8: 15.1:

Atheist propaganda against mosques

IRPT leader Mullah Sayid Abdullohi Nuri at peace talks

Haji Akbar Turajonzoda, deputy head of the MIRT

Funeral ceremony for Muhammadsharif Himmatzoda, the IRP

T’s first political leader

Leaders of the IRPT

Muhiddin Kabiri’s Outreach on Twitter

Adolat leader Tohir Yo’ldosh challenges President Islom Karimo v, Namangan, 1991

The IMU’s martyr, Shaykh Abduvali Qori

Women visit a mosque in Bukhara

Warning poster, hung at a mosque in Khiva, showing alleged e xtremists

Propaganda video of IMU suicide assault team

Propaganda video of IMU leader Shaykh Muhammad Tohir For uq Yo’ldosh in Afghanistan

Jumanamazat Imam Sulaiman-Too Mosque in Osh

Imam Sarakhsi Mosque in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

Imam Rafiq Qori, Kara-Suu

KTJ battalion training in Syria

From “The Hijra”

Abu Saloh, leader of Katibat al-Tawhid wal Jihad

Abu Saloh—“Are You Afraid to Go to Jihad?”

Abu Saloh—“Jihad is the Way of Honor!”

Abu Saloh—“About the Virgin Servants”

Abu Saloh—“The Shahid’s Reward”

Tajik Colonel Gulmurod Halimov in ISIS video

“One more friend of mine became a shahid”

List of Tables

I.1: I.2: 3.1: 12.1: 14.1: 14.2: A.1:

Waves of Muslim and Islamist Mobilization, 1917–2022

Islamist Organizations, their Characteristics, and Relative Level of Mass Mobilization, 1990–2022

Registered Friday Mosques in Several Muslim-Majority Republic s

Registered Mosques and Muslim Population, 2015

Foreign Fighters Joining Sunni Militant Islamist Organizations i n Syria and Iraq

Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq by Region, 2017

Focus Group Interviews

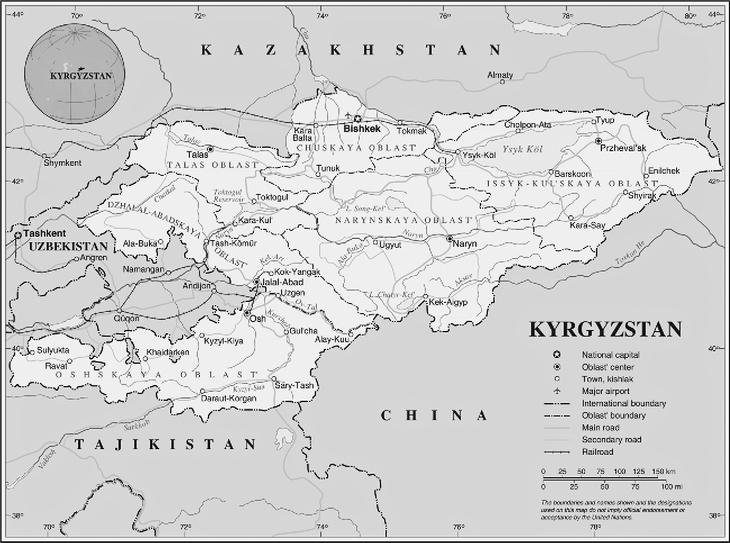

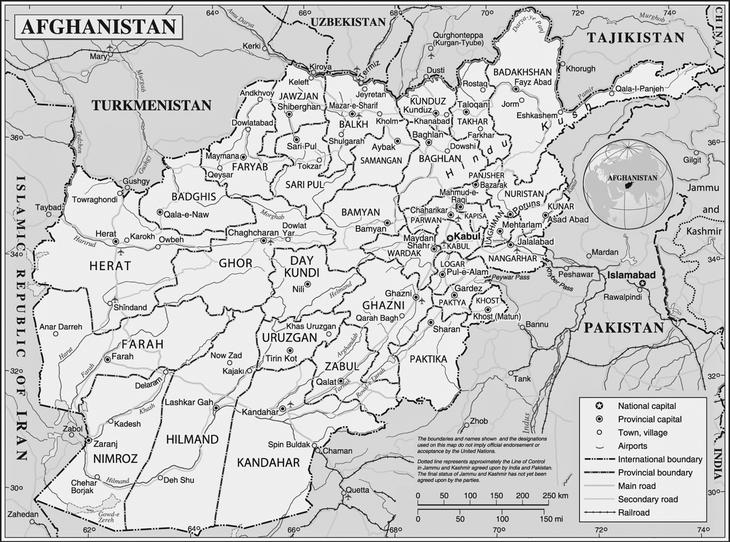

List of Maps

Map of Central Asia

Map of Tajikistan

Map of Uzbekistan

Map of Kyrgyzstan

Map of Afghanistan

Map 9.1:

Map 14.1:

Location of IMU and insurgent operations in Afghanistan, 2010

Location and control of Central Asian al-Qaeda–linked figh ters in Syria, March 2018

Acknowledgments

One of the things I have often admired about Central Asians, from those living in remote villages to those in dense urban mahallas (neighborhoods), is their ability to persist despite adversity. Their faith and endurance motivated me to continue with this book, which has been a long time in the making. My Central Asian friends and I have often shared our hopes for a better future. I pray this book makes a small contribution to that future, both by remembering the past and by reminding readers of the basic human need for justice and religious freedom.

During the years that I have worked on this book, I have been able to observe Islamism in Central Asia as it has developed and changed. My project grew as Islamism of many forms evolved and spread across the region, from Tajikistan to Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. I became all too aware of the complexity of the Islamist phenomenon. Some, like the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, shifted from an early focus on President Islom Karimov’s regime to attacking U.S. forces in Afghanistan, and then waging jihad in Syria. Most Islamists in Tajikistan, by contrast, moderated and were willing to speak with me about their desire for democracy and religious freedom. My eyes were opened as they recounted how the “Red Terror” had triggered their demands for justice. Caught between the state’s religious oppression and the violence perpetrated by some Islamists were ordinary Muslims, men and women seeking a better life for their children, as do people everywhere. As an Uzbek cab driver once told me, “You’re Christian, I’m Muslim, but there’s just one God.”

Over the years, I have worked closely with wonderful colleagues and assistants throughout Central Asia; they have become dear friends. Together we have watched—and they have lived through—

the turmoil of politics and everyday existence in the region. Throughout this time, I have relied on them and many other good people there for help. Given continued political oppression and uncertainty, I have chosen not to name most of them here. I hope that they know how grateful I am and how much I have learned from them. I truly appreciate the advice, knowledge, and friendship of Elvira Ilibezova and El-Pikr in Kyrgyzstan. I thank Saodat Olimova, Muzaffar Olimov, and Muhiddin Kabiri in Tajikistan. Ercan Murat, Emil Nasritdinov, Keneshbek, Esen, Hassan and his family, Hurmat, Dinara, Parviz, Murat, Dilbar, Tolekan, and many others shared their knowledge, helped arrange meetings, and got me safely from Bishkek to Kara-Suu, from Tashkent to Andijon, and from Khujand to Dushanbe, among many other places. Central Asian journalists and human rights activists who risk their lives every day offered me their assistance. Those who drove me around cities and villages, through the mountain passes, and across the steppe of Central Asia all deserve far more than my heartfelt thanks. Others poured me tea, brought me warm meals, kept me safe and healthy, and became my friends. Many took risks because they wanted me to tell their story.

The U.S. embassies, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, and United Nations Development Programme in Tashkent, Bishkek, and Dushanbe provided support and insight, as did Robin Schulman, Greg Taubman, Kelly Kivler, Daniel Burghart, and David Abramson. Damon Mehl and Chris Borg offered a wealth of expertise on militants in Afghanistan. Ismail Yaylacı and Selçuk Köseoğlu assisted me in Turkey, and Valery Tishkov in Russia. David Holloway nominated me for the Carnegie grant that funded the initial stages of this project. My mentor at Notre Dame, Jim McAdams, encouraged me never to forget the human side of my work. His wisdom and copious comments greatly improved this manuscript. Scott Mainwaring, Kathryn Sikkink, and Sid Tarrow were especially generous with their counsel. Bayram Balcı, Stéphane Dudoignon, Steve Fish, Fran Hagopian, Valerie Bunce, Laura Adams, Carrie Rosefsky, Kathryn Hendley, Amaney Jamal, Mark Tessler, Eric McGlinchey, John Heathershaw, Ted Gerber, and David Samuels, among others, offered advice. Adam Casey, Shoshanna Keller, Alisher

Khamidov, Adeeb Khalid, and Jeff Sahadeo each thoughtfully read several chapters. My dear Uzbek friend and colleague provided feedback on the Uzbekistan chapters. I have learned so much from him over the years, and he has been a steady source of inspiration. Farhad greatly assisted me with Abu Saloh’s videos. Esen translated Kyrgyz, Zamira and Marifat translated Tajik, and Mustafa Düzdağ translated Arabic sources. I am most grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for generously giving me their time and sage advice.

Lisa Hilbink, Teri Caraway, Nancy Luxon, Adrienne Edgar, and Bisi Agboola continually encouraged and reassured me. Bud Duvall, Joan Tronto, and Paul Goren always supported me. I have been blessed with many outstanding undergraduates and Ph.D. students. Niamh McIntosh-Yee, Margaux Granath, Alisher Kassym, Sasha Dunagan, Maya Mehra, Ethan Hoeschen, Natalie Melm, and especially Shawn Stefanik, Kamaan Richards, and Zamria Yusufjonova assisted at various stages. Ibrahim Öker, Selçuk Köseoğlu, and Luke Dykowski each generously read the entire manuscript and offered insight on every aspect of the book. Selçuk, more than once, painstakingly helped me proofread the text. Luke was a superb copyeditor. Their dedication has made this book far better.

The Carnegie Corporation of New York, the U.S. Institute of Peace, the National Council for East European and Eurasian Studies, the Kellogg Institute, the University of Notre Dame, the McKnight Land Grant, the Templeton Foundation, and the University of Minnesota each provided grants to finance my fieldwork and writing. I am indebted to David McBride and the production team at Oxford University Press for their superb advice, careful oversight, and cheer as they guided this project to completion.

I am especially beholden to my family—my parents, Megan, Ryan, and Tom—who have encouraged and supported my endeavors and lived through this project with me. Above all, I am infinitely grateful for my children’s love, companionship, and inspiration. My eldest, Michael, was born not long after I began my research. Michael and his younger sisters, Katie and Elisa, have brought an abundance of joy into my life. They have often sat beside me in my office or at the kitchen table, writing their own books as I wrote mine. They went

from knocking over my towering stacks of sources and colorfully scribbling on my books and notes, to solving my computer problems, helping me proofread chapters, and filing thousands of pages of interview transcripts. They endlessly encouraged me to press ahead. They cheered me on and told me they believed in me. They kept me grounded by reminding me to bake cookies and come play. I dedicate this book to them, with love.

Technical Note

Writing a book of this nature involves many complications. Uzbek, Tajik, and Kyrgyz have changed spellings and even alphabets multiple times over the past century. The names of cities, territories, countries, and institutions have changed as well. So too the geographical borders of the Central Asian states changed multiple times in the period discussed in this book.

Throughout I have sought to balance historical accuracy and cultural respect for local particularities with a reader-friendly manuscript. I have generally adopted the following guidelines for spelling and transliteration. I have retained the standard English spelling of names that are common (e.g., Ferghana, Kokand, Samarqand). For Uzbek words, I have followed the most recent Uzbek Latin script. For Turkish, I have used the Turkish Latin script. For languages written in Cyrillic (Russian, Tajik, Kyrgyz), I have transliterated titles of sources and other names and terms from the most recent spellings, using the Library of Congress system. Tajik and Kyrgyz transliterations follow the Library of Congress system for the modified Cyrillic alphabets. For example, as is common in transliteration for nonlinguists, I use gh for Ғ ғ, and j for Ҷ ҷ (e.g., Turajonzoda). I have used the most recent official spellings (e.g., Jalalabat, not Jalal-Abad). For Arabic terms or names, I have used those commonly recognized (al-Qaeda). I have dropped most diacritical marks to make the book more accessible to readers of English.

I have used the Oxford English Dictionary variant of Islamic terms that have become common in English (e.g., hijab, jihad, hajj without italics). For religious terms that differ across Tajik, Uzbek, and Kyrgyz, I have generally used the more well-known Arabic form (e.g., hadith, kafir , zakat). In deference to local culture, I have

adopted the commonly used Central Asian variants of certain frequently used terms that are distinct from the Arabic (e.g., shariat, da’watchi, namaz).

There are some issues that simply have no easy answer. I resolved them by balancing the native language names and spellings, as much as possible, with the ease of the reader. Wherever possible, I replaced Russified names of people and places (even during the Soviet era) with the current Central Asian spelling. If a Central Asian author has published in English, I used the spelling of the given publication. Acronyms reflect the native language, unless there is a commonly used acronym in English-language sources.

I attempted to verify the transliteration of every Central Asian and Arabic word, phrase, name, and place in this book (and its variations in name over time), with multiple sources, including many native speakers. Sometimes they themselves did not agree, so I defaulted to the principles above. My goal throughout the text has been to respect the Central Asian languages and cultures, maximize consistency, and ease the nonspecialist’s burden. I hope the reader will forgive any errors and focus on the substance of the work.

List of Acronyms

AKP Justice and Development Party, Turkey

ANF Al-Nusra Front

AQI Al-Qaeda in Iraq

ASSR Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic

AUIRP All-Union Islamic Revival Party

BNSR People’s Soviet Republic of Bukhara

CAISIS Central Asians in the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria

CPT Communist Party of Tajikistan

CRA Council on Religious Affairs

CTC Combating Terrorism Center

DoD Department of Defense

DPT Democratic Party of Tajikistan

ETIM East Turkestan Islamic Movement

FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas

FSB Federal Security Service, Russia

GKNB State Committee on National Security, Kyrgyzstan

GNR Government of National Reconciliation, Tajikistan

Gulag Main Directorate of Camps

GVU Head Waqf Directorate

HTI Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islami (Islamic Liberation Party)

HTS Hayat Tahrir al-Sham

ICCT International Centre for Counter-Terrorism

ICSR International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence

IED improvised explosive devices

IJU Islamic Jihad Union

IMU Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan

IRPT Islamic Revival Party of Tajikistan

IRPU Islamic Revival Party of Uzbekistan

ISAF International Security Assistance Force

ISIS Islamic State of Iraq and Syria

ISIS-K ISIS-Khorasan Province

JA Jamoati Ansorulloh, Tajikistan

KA Kokand Autonomy

KGB Committee for State Security (USSR)

KIB Katibat Imam al-Bukhari

KTJ Katibat al-Tawhid wal Jihad

MIRT Movement for the Islamic Revival of Tajikistan

MVD Ministry of Internal Affairs (the police)

MXX National Security Service, Uzbekistan (also known by the acronym SNB; since 2018, it is called the DXX, State Security Service)

NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organization

NEP New Economic Policy, USSR

NKVD People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, USSR

ODIHR OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights

OGPU Soviet secret police, predecessor to NKVD

OMI Muslim Board of Uzbekistan

OMON Interior Ministry’s Special Purpose Police Unit (or the MVD’s Special Forces), Tajikistan

OSCE Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe

RFE/RL Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty

SADUM Spiritual Administration of the Muslims of Central Asia and Kazakhstan

SAMK Spiritual Administration of the Muslims of Kyrgyzstan

SCO Shanghai Cooperation Organization

SCRA State Commission on Religious Affairs, Kyrgyzstan

SSR Soviet Socialist Republic

SUJ Seyfuddin Uzbek Jamaat

TTP Tehrik-i-Taliban of Pakistan

USCIRF U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom

UTO United Tajik Opposition

WMD weapons of mass destruction

Map of Central Asia

Source: Wikimedia Commons

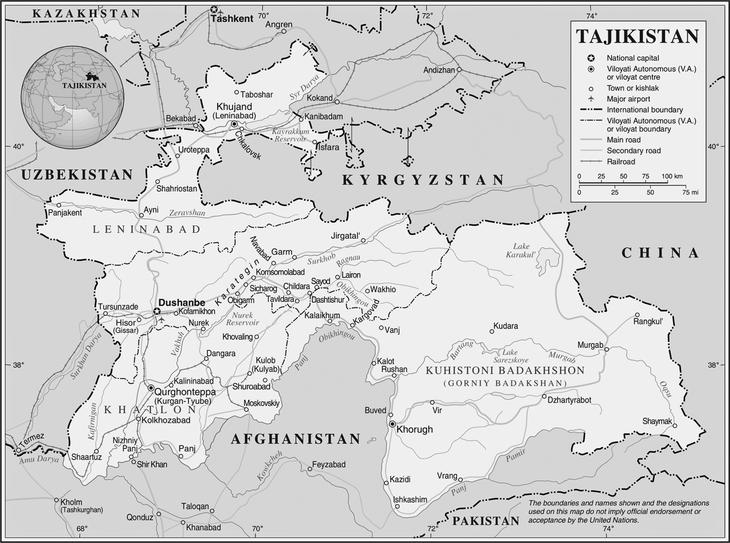

Source: United Nations Cartographic Section, Wikimedia Commons

Map of Tajikistan

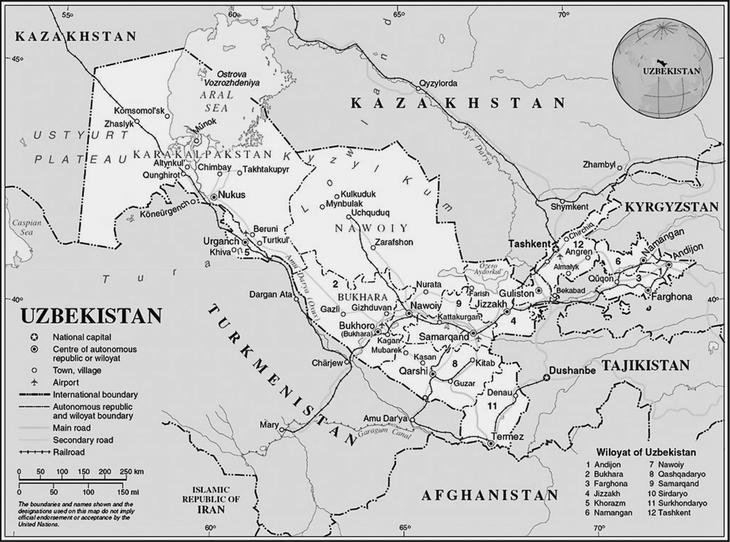

of Uzbekistan

Source: United Nations Cartographic Section, Wikimedia Commons

Map

Source: United Nations Cartographic Section, Wikimedia Commons

Map of Kyrgyzstan

Map of Afghanistan

Source: United Nations Cartographic Section, Wikimedia Commons