Plato s Philebus

A Philosophical Discussion

Edited by PANOS DIMAS, RUSSELL E. JONES, AND GABRIEL R. LEAR

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Great ClarendonStreet, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department ofthe University ofOxford. It furthers the University s objective ofexcellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxfordis a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK andin certain other countries © theseveral contributors 2019

The moral rights ofthe authors have been asserted

First Edition published in 2019

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. Nopart ofthis publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing ofOxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or underterms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope ofthe aboveshouldbe sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You mustnotcirculate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States ofAmerica by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States ofAmerica

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Dataavailable

Library ofCongress Control Number: 2019941417

ISBN 978-0-19-880338-6

DOI: 10.1093/0s0/9780198803386.003.0001

Printed and boundin Great Britain by Clays Ltd, ElcografS.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in anythird party website referenced in this work.

Preface

During a meeting at the Norwegian Institute at Athens in December2013,Pierre Destrée, Susan Sauvé MeyerandI agreedthat Plato scholarship wouldprofitfrom an undertaking similar in scope and aim to the Symposium Aristotelicum. Fully appreciative of the fact that the Platonic dialogues pose a different and more complex interpretative challenge than do the various Aristotelian texts, we nonetheless concluded that the potential rewards of such an undertaking madeit worthwhile. We proceeded to consult with Francesco Ademollo, Christoph Horn, Gabriel Richardson Lear, and Marco Zingano, who endorsed the idea and accepted our invitation to join in the effort to realize the plan. Thus the Plato Dialogue Project (PDP) cameto be, with the seven ofusas its steering board.

Ouraim is for the Plato Dialogue Project to becomea central research forum for Platonic scholarship. We plan to hold meetings every third year at different research institutions around the world, with each meeting devoted to a single Platonic work. For each meeting, the text is divided in sections, with each portion assignedtoascholarwhohasbeeninvitedtowriteapaperaboutit.Thepapersare presented at the meeting, where they receive feedback andcriticism from the assembled participants, and are subsequently revised for publication in a single volume. Centraltothisenterpriseistheconcern thattheentirePlatonictextunder study, notjust selected parts, be subject to rigorous philosophical analysis.

The Plato Dialogue Project hadits first session at the Anargyrios and Korgialenios School in the Isle of Spetses, Greece in September 2015. The Norwegian InstituteatAthenshostedthe meetingandwearegrateful forits support. Thetext chosen was the Philebus and the volumebefore youis the result ofthose deliberations. In addition to the contributors to the volume, the participants included Francesco Ademollo, Paul Kalligas, Keith McPartland, Franco Trivigno, and Marco Zingano.

The PDPsteering board: Francesco Ademollo, Pierre Destrée, Panos Dimas, Christoph Horn, Gabriel Richardson Lear, Susan Sauvé Meyer, Marco Zingano

On behalfofthe steering board: Panos Dimas

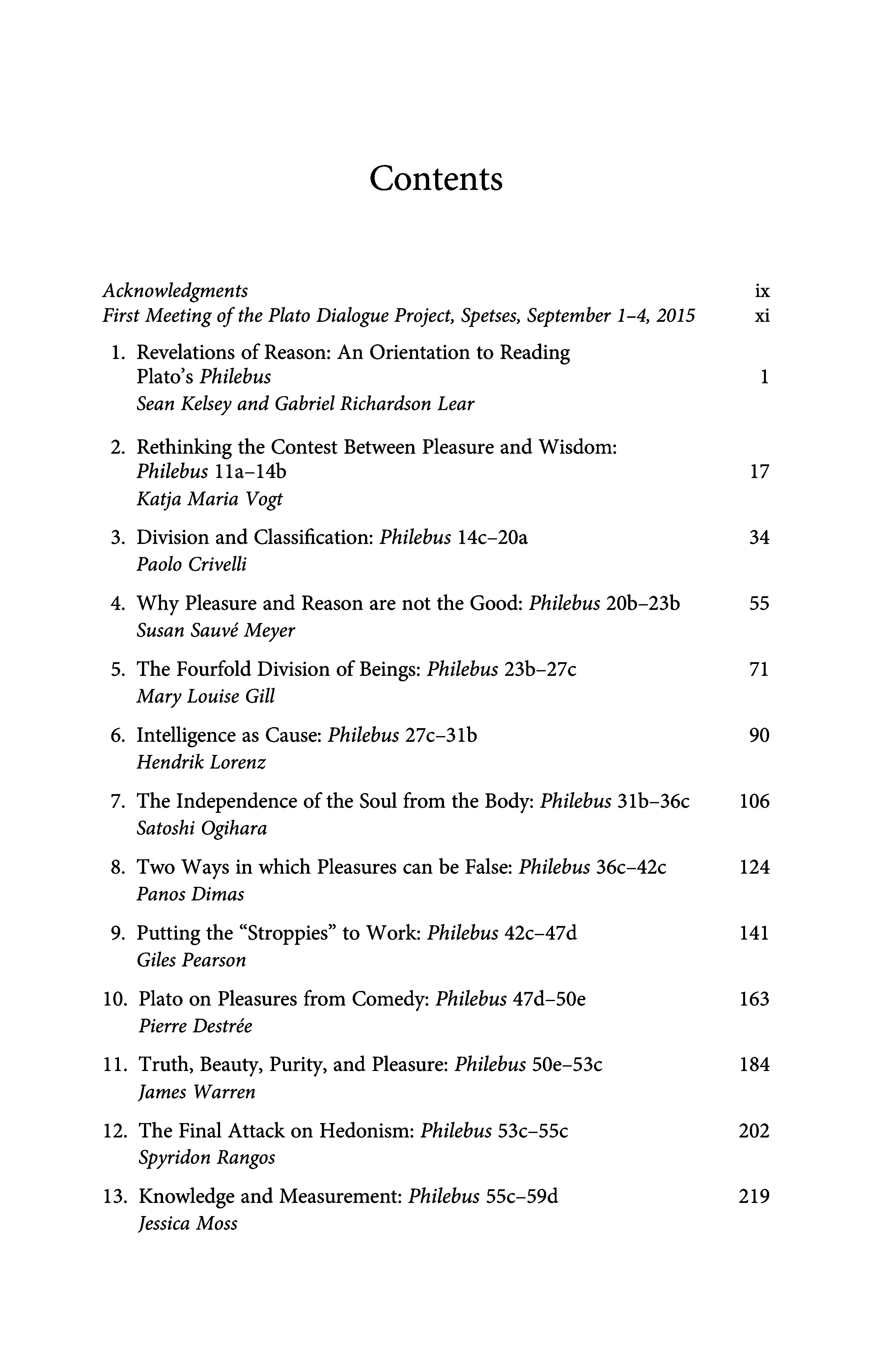

Acknowledgments

First Meetingofthe Plato Dialogue Project, Spetses, September 1-4, 2015

Revelations ofReason: An Orientation to Reading

Plato s Philebus

Sean Kelsey and Gabriel Richardson Lear

. Rethinking the Contest Between Pleasure and Wisdom: Philebus 11a-14b

Katja Maria Vogt

. Division and Classification: Philebus 14c-20a

Paolo Crivelli

. WhyPleasure and Reason are not the Good: Philebus 20b-23b

Susan Sauvé Meyer

. The Fourfold Division ofBeings: Philebus 23b-27c

Mary Louise Gill

. Intelligence as Cause: Philebus 27c-31b

Hendrik Lorenz

. The Independenceofthe Soul from the Body: Philebus 31b-36c

Satoshi Ogihara

. Two Waysin which Pleasures can be False: Philebus 36c 42c

Panos Dimas

. Putting the Stroppies to Work: Philebus 42c-47d

Giles Pearson

Plato on Pleasures from Comedy: Philebus 47d-50e

Pierre Destrée

Truth, Beauty, Purity, and Pleasure: Philebus 50e-53c

James Warren

The Final Attack on Hedonism: Philebus 53c-55c

Spyridon Rangos

Knowledge and Measurement: Philebus 55c-59d

Jessica Moss

14. Cooking Up the GoodLife with Socrates: Philebus 59d-64c

RussellE. Jones

15. The Dialogue s Finale: Philebus 64c-67b

Verity Harte Bibliography

Revelations of Reason

An Orientation to Reading Plato s Philebus

Sean Kelsey and Gabriel Richardson Lear

The essays comprising this volumeare each focused ona relatively briefsection ofthe Philebus and are arranged in the order ofthe passages they discuss. They originated in aweek-longseminar,thefirstofthe PlatoDialogue Project, inwhich the contributors were asked to offeran overview ofthe argumentoftheirpassage, focusing on issues ofphilosophical significance as they saw fit. The conversation continued over subsequent months, as the contributors exchanged written comments on each other s papers. The result is not and is not intended to be a commentary, nor does it aim to present a unified interpretation. It is instead a series of close, original philosophical examinations, often in conversation with each other, which together provide continuous coverage ofthe Philebus.

Asthe essays in this volumereveal, the Philebus is an extraordinarily creative and profound work of philosophy, addressing questions of philosophical methodology, moral psychology, ontology, and ethics. We cannotvindicate that claim in a briefintroduction and in any case that is the cumulative work ofthe essays which follow,workwhich it wouldatbestbe redundant to summarize. Instead,in thinking about howto introduce thisvolume, wethought it mightbe useful to say something about how the parts of the dialogue examined in these essays fit together as a whole, both by way ofreminder and because, as we explain below, theargumentativeintegrityofthePhilebusstrikesusaspeculiarlyelusive (afeeling evidentlyshared bymanyreaders). We diagnose two sourcesofthis difficultyand offerasuggestion ourown,notthecontributors abouthowtoorientoneselfto the dialogical whole ofwhich the passages discussed in these essays are parts.

Therebeingworseplaces to startthanthe end, webeginwith Socrates last remark in the Philebus, which (apart from a request tobe released from the conversation) reads as follows:

In anycase [thepowerofpleasureis] notfirst [in the ranking], not evenifallthe cattle and horses andall the other beasts, by their pursuit ofenjoyment, should say that it is trusting in whom,as augursin birds, the manyjudge pleasures to

© the several contributors. DOI: 10.1093/0s0/9780198803386.003.0001

Sean Kelsey and Gabriel Richardson Lear, Revelations ofR An Orientation to Reading Plato s Philebus. In: Plato s Philebus: A Philosophical Discussion. Edited by: Panos Dimas, Russell E. Jones, and Gabriel R. Lear, Oxford University Press (2019).

be most decisive for ourliving well, and suppose that the longings ofbeasts are authoritative witnesses, rather than those of the prophetic statements made underthe guidance ofthe philosophic Muse. (67b1-7)

The remarkis interesting for what it hints about Socrates larger objective in the precedingdiscussion.Earlier, helet slip that hewas fedupwith the statementthat the goodfor us is pleasure (66d-e); here he reveals whyhe was fed up: not simply because the statementis false, but because its many proponents have morefaith inthetestimonyofbeaststhan ofphilosophicallyinspireddiscourse. This suggests thatSocrates own aimwasnotmerelytoreacha conclusion aboutthe statement s truth (11c), but also to enhance the credibility of his own star witnesses, whose testimony is revealed by their longings and aspirations. That is to say, Socrates wishes not merely to have the testimony of philosophical arguments put on record,butalso to increase their standing so that his audience will not only hear but also believe them. Wereturn to this suggestion below, because wethinkit is helpful in relation to some aspects of the dialogue many readers have found puzzling.

WhateverSocrates personal objectives, the discussion s official agenda is clear enough. Protarchus, having taken over from Philebus the statement that pleasure is good for all animals, must try to show that pleasure is a condition of soul capable offurnishinga happylife to allhuman beings (11d); Socrates must tryto show the same about wisdom (phronésis). In addition,it is agreed that, should someotherthingprove superiortobothpleasureandwisdom,then althoughboth Socrates and Protarchuswill stand defeated by thelife firmly possessed ofthat, still, wisdom will be defeated by pleasure (or vice versa), depending on whichis more akin (sungenés) to that other (11d-12a, cf. 22d-e). This agenda is made clear at the outset, and when we cometo the endofthe dialogue,it is these same points that are now taken as settled: as Socrates formulates it there, neither pleasure nor wisdom is the gooditself, and (as compared to pleasure) reason (nous) is ten-thousand times more akin (oikeioteron) and more attached to the idea ofthe victor, i.e., the gooditself (67a).

1. The Dialogue as a Whole

Despite this apparent consonance and clarity of purpose, many readers have found it difficult to grasp the project of the Philebus and its argument as a whole. Onedifficulty is that it is not easy to see how the dialogue s several parts fit together so as to form a single line ofargument. Now,it is often an effect of

Earlier Socrates claimed that, for those creatures capable of sharing in it, wisdom is better than pleasure, and indeed thatit is the most beneficial ofall things (11b-c).

Plato s dialogueform thatthe conversationbetween Socrates andhis interlocutors meanders from onetopic to another, following a structure that is more narrative than it is deductive. However, in thePhilebus Plato seems to emphasizethatthere isasingle agendaandthateverytopic SocratesandProtarchusdiscuss isnecessary or at least helpful for securing Socrates conclusion. Thatis to say, Plato raises the reader s expectation of a clear line of logical connection among the dialogue s parts. And yet, when we look moreclosely it is often unclear where or how those discussions are putto use.

A notorious example of this problem first arises near the beginning of the dialogue,theinvolveddiscussion ofthe divine method, whichinstructs usnotto let go ofthe objects ofour inquiries (certain unities ) not to release them into the unlimited before having told their entire number, i-e., enumerated all oftheir finitely manykinds (12b-20a). There are manydifficulties concerning the proper interpretation of the internal dialectic of this passage how many problems is the divine method supposed to solve and howis it supposed to solve them?? but we focus rather on how the passage as a wholefits into the larger argumentative flow. The discussion ofthis method is prompted by thefact that the interlocutors examination of pleasure founders almost immediately, as Socrates has difficulty securing Protarchus agreement to his very first point (namely, that pleasure comes in a variety of forms that are unlike and indeed opposed to one another) (12c-13d). Onecuriosity is that though the principal causes of this difficulty appear to be moral Socrates complains that they ve been obstinate, defensive, immature, outrageous, evasive, and partisan (13c-d, 14a-b) the ensuing discussion of method, which is supposed to help remedy these deficiencies, is introduced as reinforcing a fairly technical point about one and many, andis touted for its power ofsteering clear ofvarious difficulties that this point gives rise to (14c, 16a-b). Even morestriking, after describing this method, and claiming thatit is what distinguishes dialectical from eristic discussion (17a), and declaring that the argument demands that they show how [pleasure and knowledge] each are one and many (18e-19a), Socrates more or less immediately proceeds to disregard it entirely. Instead, without benefit of having collected or divided either pleasure or knowledge into kinds, he argues that thegood isneitherofthembut rather somethird thing,different from and better than them both (20b-c). Though the divine method maybenecessary for something, it is apparently not necessary for resolving the first point at issue between Socrates and Protarchus, whether it is pleasure or knowledge that is capable offurnishing ahappylifeto all humanbeings. For that point is resolved

? See Crivelli, this volume, Chapter3, for a novel solution that, among other things, sees Plato as trying to maintain the unchanging and non-spatial character ofgenera andspecies by conceiving of collection and division as matters of identifying relations of subordination and disjunction (as appropriate) among genus, species, andsensible particulars.

by Protarchus intuitive sense that neither thelife ofpleasure alone northelife of reason alone would be desirable, with the result that neither pleasure nor reason meets the formal requirement that the good be complete (teleon), sufficient (hikanon), and unconditionally desirable (20c-d).?

Perhaps the methodis put to use in the ensuing discussion of the winner of secondprize ? Afterall, though Socrates verynext pointis that this discussionis going to require some other contrivance some new arrows, as it were, different from those employed in the preceding discussions he also remarks that perhaps somewill be the same (23b). The new equipmentitselfis apparently the division of all beings into four kinds (unlimited, limit, mixture, and cause), which Socratesthen uses to classifypleasure, reason, and the mixedlife superior to both, assigning one each to three of the foregoing four kinds (23b-27c, 27c-31a). But though thefirst part ofthis discussion certainly does make use of the vocabulary of division, it is far from a straightforward application of the methoddescribed earlier (12b-20a). Socrates turns the methodonitself, treating someof its structural features limit, unlimited as themselves objects to be collected and divided. Several scholars have doubted whether such a procedure allowsfor aunivocal senseof unlimited ; and Socrates himselfdraws attentionto his failure actually to delimit or state the determinate numberofthe category of limit itself (26c-d)!*

At any rate, in the second part ofthis discussion, Socrates (on the strength of the testimony of Philebus) assigns pleasure to the kind unlimited and (on the basis ofhis own argument) assigns reason to the kind cause, so as to help settle thequestionofwhetherwisdomisbetterthanpleasure. Now,itcertainlylookedas though secondprize wasgoingtobe awardedtothe cause ofthecombinedlife (22d). But andhere is a second example ofthe problem weare discussing the argument that assigns reason to the kind cause does not, in fact, decide the contest (notwithstanding the importance Socrates attaches to makingthis assignment correctly (28a)). For it takes them nearly forty Stephanus pages more to reach a final decision. Equally puzzling, the argumentthat assigns reason to the kind causeis in fact an extended discussion ofa divine, cosmic reason, which(it is argued) is responsible for the beautiful order of the cosmos (30c). Fascinating though this maybein itself, however, we might have expected Socrates argument to focus on humanreason.° Theresult is an unsettling sense that the foregoing discussion is (at best) out of proportion with its contribution to the particular

> Following Meyer, who arguesin her contribution to this volume (Chapter4) thatthere are indeed three separate criteria ofthe good atissue in this passage.

* Gill emphasizesthis point in her contribution to this volume (Chapter 5) as part ofa larger (and provocative) argumentagainstthewidespreadinterpretationofalllimitsasharmoniesandallmixtures as good andbeautiful.

° Whetherthisdivineintelligenceis the intelligenceresidingin theworld soulorisrather, as Lorenz arguesinthisvolume (Chapter6),anintelligencetranscendingthecosmosandpriortoallsoul,itisnot humanintelligence.

questionthatSocratesprofessestobeengageduponsettling, aswellasconsiderable unclarity about what precisely the fourfold division ofbeings is supposed to have accomplished.

Maybe we should look for Socrates to employ the divine method in the subsequentdiscussions ofpleasure andknowledge;afterall, these arethe unities that we were led to think require a full accounting in the first place (19a-b), and the discussion ofthem comprises more than halfofthe entire dialogue (31b-59d, 59e-64b). This discussion, and especially the discussion of pleasure, is indeed a tour de force: Socrates describes several distinct kinds of pleasure in glorious psychological detail, and also (though to a lesser extent) several kinds ofknowledge. But if he is here employing the method described earlier, he hardly emphasizes that fact. For example, the discussion is at least introduced as an inquiry, not into the various kinds ofpleasure and knowledge, but into the seat and cause ofeach ofthem respectively (év @ ré éorw Exdrepov abroiv Kai dia Ti ma0os yiyveoBov, 31b). Moreover, though several kinds (eidé) of pleasure are indeed discussed in sequence (note e.g., the transition at 32b-c), there is no obvious attempt at any final reckoning, such as would tell the whole number ofeither pleasure or wisdom, nor even (perhaps) to collect either ofthem under a single, common account.® Again, manyofthe different forms ofpleasure, and all of the different forms of reason or wisdom, are distinguished from one anotherby their varying degrees of purity and truth indeed,in retrospectit appearsas thoughthis is preciselywhat Socrates wasafterall along (55c). Butit is at least not obvious that these are the differences that divide a kind (genos) into its varieties or forms (eidé). For example, Socratesearlier spoke as though the differentforms ofakind areformsofthatkindequally(e.g., thedifferent colorsor shapes are equally colors or equally shapes) (12e-13b);it is at least not clear that he would say the same about varieties of pleasure or wisdom that differ

° NotethatthoughearlierSocratesconcedes,indeferencetothetestimonyofPhilebus,thatpleasure and pain belong in the kind unlimited (rodrw 5% cou rev drrepdvtwv ye yevous éotwy, 28a), his first point in the later discussion ofpleasure is that its natural seat is the combined class (év 7@ cow yever...yiyvecBat kata pdotv, 31c); indeed he goes further, describing pleasureitself as the natural path () xara pvow686s, 32a), ie., the path to being ofcreatures that experience pleasure (1 eis r7)v aita@v odciav 656s, 32b) descriptions which evoke his earlier characterization of the third kind as generation into being (yéveors eis odaiav, 26d). (We note that the fact that Socrates concession to Philebusis just that a concession is perhaps anticipated earlier, where he says,pace Philebus, that law and order(i.e., limit), far from effacing (doxvaica:) pleasure, has kept her safe (d7ocdcaz), 26b-c (though see 41d, where the concession is recalled and reaffirmed).)

The question ofwhether or not Socrates articulates or indicates a unified account of pleasure as filling or restoration ofa harmoniousstate from state ofdeficiency is a subject ofdispute among Ogihara (Chapter7), Rangos (Chapter 12), andWarren (Chapter 11) in thisvolume.Itis closelyrelated to the question, discussedby Rangos, ofthe sense in which all pleasures, including the pure pleasures, maybesaid to be membersofthe unlimited class in the fourfold ontology. However, as Moss notesin her contribution to this volume (Chapter 13), comparing kinds of knowledgein termsoftheir relativepuritydoessuggestthatthere is some unifiedaccountapplicableto them all in some wayorother. Accordingto her interpretation, knowledgeis in everycase a matter of measuring or perhaps more generally grasping limits.

substantiallyfromoneanotherinpurityortruth.* Onceagain,then,thedialectical method discussed at such length does not obviously find a straightforward application in the dialogue. To beclear, we are not insisting that Socrates makes no use of this method, or that he nowhere collects or divides either pleasure or knowledge into one or more determinate kinds; our point isjust that the method does not shape and control the subsequent discussion in the way weare led to expect, by the fanfare with which it is introduced, by the length at whichit is described, andbythe importanceassignedto it, as shownbythe exampleofthose contemporary savants, whom the intermediate [kinds] escape (rapeoaadrods éxgevyet), which kinds makeall the difference for whether or not a discussionis conductederistically (ofs diaxeyasprora: 76 Te SuadexTiKads TAAL Kal TO éptoTLKaS Hpas trovetaba pds GAAHAOUs Tods Adyous, 17a). Tobe sure, there are severalways one might try resolving the interpretive challenge this poses indeed, several essays in this volume make important contributions to our understanding in this regard. Our pointis simply thatit is indeed a challenge. Even morestrikingwith respecttothelargerpointwe aremaking:it isnotclear howthe magisterial discussions ofpleasure and knowledge themselves contribute to the final decision about pleasure and wisdom (and this despite Socrates remark, concerning the discussion of false pleasures, that perhaps we'll use this in reaching final decision (41b, cf. 32c-d, 44d, 50e, 52e)). Recall how that argument goes: Socrates wants to determine which of pleasure or knowledgeis more akin to the good. To do that he mustfirst identify the good, something he proposes to do by mixing pleasure and knowledge into a good life and seeing wherethatlife sgoodnesslies. Now, the fact that the differentvarieties ofpleasure andwisdom are not equally pure or true certainlybears on thecomposition of

* Consider that the lowest form of knowledge in the Philebus practices which the manycall crafts is a matter ofempeiria (experience) and tribé (knack), rather than ofmeasurement (55e-56a). In the Gorgias, Socrates argued that such practices were notin fact crafts at all, but only appearto be. Has he changed his mind? Again, Socrates does claim that what takes pleasure, whether rightly or wrongly, reallydoestakepleasure (76 ddpevor,ave6p0dsdvrepur} pOasRdnTaL, 7dyedvTwsYSeo0ar diAov cbs obdemore arroAei, 37b); still, he also claims that some pleasures are false, being laughable imitations oftrue ones (uepipnuevar tas dAnOets emi Ta yeAowdTepa, 40c). Ifthese caricatures oftrue pleasuresreallyare pleasures,is it clear that they are pleasures on an ontological par with the genuine article?

° Consider, forexample, D. Frede s radical response to this problem: Whydid Socrates so emphasize the demandthat the divisions must be complete and numerically exact, ifhe did not care to follow this rule himself? And why does hestress that no one who does notfollow the rules is ever to count as competentat anything, ifhe thereby denigrates his own effort? The mostplausible answeris that Plato wanted to make crystal clear what he is not doing in the Philebus. He wants to leave no doubt that although someuse is made ofthelawsofdialectic, his investigation ofpleasure andknowledge cannotbe called dialectic proper [...] By foregoing a systematic dialectical treatmentofall kinds ofpleasure and knowledge, the partners forfeit their claim to expertise in thosefields (1993, xli). By contrast, Fletcher (2017) explainsmanyoftheperplexitieswehavepointedtobycastingthem asstagesofSocrates attempt to persuade Protarchus that pleasure is not somesingle kind ofthing atall. His failure to collect a unity anddivide it into a determinate numberofkinds is not a failure ofhis application ofthe method or a forfeitingofaclaimtoexpertise,butratherafailureofpleasuretobeaunifiedkindofthesortconcerning which there could evenin principle be an expertise.

the mixture that is the good life (59e-64b). Whereasall varieties ofknowledge are admitted, many(all?) ofthe false and impure formsofpleasure are not. Even so, the decision that wisdom is better than pleasure is not based on wisdom s making a greater or even better contribution to that mixture. ® No, that decision is reached by comparing pleasure as a whole and wisdom as a whole (without explicit reference to their several varieties) to the good-makingtriple of truth, measure,andbeauty(65a-66c). Moreover,eventhoughmixingthegoodlife requiresattentiontothe factthatthere aremanydifferentkindsofpleasure and of knowledge, Socrates characterization of these kinds here is not nearly as finegrained as his previous discussions permit. Those discussions are far more intricate and involved than is strictly required by the logic ofhis argument.

Wehavebeentryingtoconveysomethingofwhyreadershavefoundit difficult to see howthe Philebus hangs together howits various parts combine to make a moreorlesssingle,linear,andcoherentcaseforthedialogue sofficialconclusions. Those conclusions (again) were two:first, that the good is neither wisdom nor pleasure, and second, that wisdom is better shares in a greater portion ofthe good, is many-times moreakin to the idea ofit (60b, 67a) than pleasure. The difficulty might be put as follows. First, the official arguments for these conclusions, which take up but a fragment ofthe dialogue (20b-22c and 64c-67b), do not obviously draw any oftheir premises from any ofthe dialogue s other main sections: not from the discourse on method (12b-20a), not from the fourfold classification ofbeings and its application to pleasure and reason (23c-31a), not even from the long discussions of pleasure and reason themselves (31b-59d). Second,neitheris itobvioushowthese mainsections interactwith and depend on one another.It is therefore difficult tograsp what rationallypersuasiveworkthese various discussions are intended to do. To besure,they are all obviously relevant tothe dialogue sbroadertopic. Whatisperplexing is ratherthat, inthosepassages containing the dialogue s crucial argumentative cruxes, Socrates does not explicitly appeal to any specific claims established or examined previously. We emphasize that none of this in any way denigrates the inherent philosophical interest ofthese discussions (no doubt that is whythe discussionsofdialectic and ofpleasure havebeen the objects ofparticular scholarlyattention).Still, iftheydo not provide premises or methodologies for later arguments, how exactly are they

° Webelieve this is so even if, as Jones argues in this volume (Chapter 14), the mixing passage shows that knowledge has a structurally important role in the goodlife not played by pleasure. To anticipate a suggestion we will make shortly, the mixing passage does indeed show the superiority of knowledgeto pleasure, butit is not the official argument for this conclusion.

" For example, though oneofthe most distinctive features ofSocrates approach to pleasure is to argue thatmanyofits formsare false, when it comes time to decide which pleasures are to be mixed into the goodlife, the pleasures that are refused entry, though contrastedwith those pleasures that are true and pure, are described as greatest (megistas) and most intense (sphodrotatas), and are rejected on the grounds,not that they are false, but that they are constant companionsoffolly and vice (det per dgpootyys Kai THs GAAns Kaxias éropévas, 63e).

intended to contribute to establishing the dialogue s official conclusions? Some might attribute Plato s lack of precision about the overarching argumentto the fact that the Philebus was likely written late in his life, when his artistic powers were beginning to wane; his makrologia (as it might seem) on thetopics of dialectic, cosmic nous, and pleasure mightbe attributed to the fact that at this late stage he had manyideas he wantedto put into writing somewhere and the theme ofthis dialogue provided a relevant venue. We consider these explanations to be interpretationsoflast resort. ? Wewill offer an alternative in a moment,butfirst let us examine a second problem facing readers ofthe Philebus.

2. The Importance ofPlacing Second

Normally, a good way ofgrasping the logical structure of a discussion is to get clear on whatits point is. But the second problemis figuring out what exactlythe project ofthis dialogueis. *

Afewthingsare clear. First, in thePhilebusPlato hasa familiar figure (Socrates) returning to a familiar theme, viz. the contest between two ways oflife, one devoted to pleasure, the other to philosophy.It is true that here the contestants are largely shorn of associations prominentin other dialogues: for example, the association ofphilosophywithjustice, or ofpleasure with tyranny (the aspiration for which is sometimes disguised as ambition for political distinction). ° But though the setting and preoccupations of the Philebus are, by contrast with many other dialogues, markedly a-political, its principal topic is a familiar one. Forit is at least arguable that the teaching of (say) the Gorgias or Republic is that while the happy and just are marked by their commitment toreality or truth, the unjust and unhappyare at bottom driven on by desire for pleasure.

Second,in treating its topic, the Philebus showsrelatively little interest in what we might call the good,i-e., the very form or idea ofgoodness, the gooditself. Forits declared focus, from the very beginning,is limited: not the good as such, but the good for us, for us living creatures, above all for us human beings. ®

WethankRachel Barney for pushing us to consider this possible explanation, mentioned also in Barney (2016, 209) in connection with another odd momentin the argumentofthe Philebus.

1 SeelikewiseCrivelli(2012,8),whorejectsthissortofexplanationforasimilarproblemabouthow to understand the relevance of the divine method to the puzzles raised about the unities as uncharitable.

'* This problem andthe related problem ofgraspingwhatis special about the approachto ethics in the Philebus are addressed by several essays in this volume, especially Vogt (Chapter2), Meyer (Chapter4), Jones (Chapter 14), and Harte (Chapter15).

® Though the unexpected reference to Gorgias at 58a-c suggests that political concerns are somehowatissue in the dialogue.

*6 Thispoint isemphasizedbyVogt, whoarguesinhercontribution to thisvolume(Chapter2) that this starting point allows Plato to adopt a novel approach to familiar ethical themes, an approach focusedonthepluralityofgoodmakingfeaturesofthehappyhumanlifeandcallingupona distinctive metaphysics ofmixture.

So, what Socrates and Protarchusare to prove about pleasure or wisdomisthat it is the condition ofsoul capable ofmakinglife happy for all human beings ( év puyns kal didBeow... rHv Suvapevnv avOpwmois waot Tov Biov eddaipova Tapéxerv) (11d). It is true that the Philebus does contain some remarks that are at least ostensiblyabout the good: forexample,thatitisperfect,choiceworthy, andgood in everyway, or that it maybe graspedbythe triple ofbeauty, measure, and truth (20d-21a; 61a, 64e-65a). But these remarksare in the service ofpoints about the human good,i.e., agood that inhabits akind ofhumanlife, a mixture ofboth pleasure and wisdom.

Third, and perhaps mostdistinctively, the bulk ofthe Philebus is addressed to the comparativevalue ofpleasure andwisdom.It s agreed fairly earlythat neither wins gold : thatis, that neither is the good for us humanbeings. Thereafterthe question is which will win silver a question Socrates apparently cares more about than which(ifeither) wins gold (22a)!

It sjust here, we believe, that difficulties arise about making sense ofthe larger project ofthe Philebus as a whole. Onedifficulty is simply about what question this is,ie., aboutthecriterionbywhichitwillbedecided. Thoughinplacesitlooks as though the question is causal, with second prize going to the item responsible for the mixed life (22d), elsewhere it looks as though it will be decided by similarity or kinship, with second prize going to the item that is more similar andmoreakin towhateverit isthat makes the mixedlife choiceworthyandgood (22d) or(if this is different) to the idea of the good itself (60b) while in still other places it looks as though the question is quite simply which is better, with secondprize goingto the itemthat shares in agreaterportion of thegood (67a). So, how many questions is this, and (if they are more than one) how are they related? * A second difficulty, connected to thefirst, is why care? What doesit matter, theoreticallyorpractically, which takes silver ? Whyis this more important, at least to Socrates, than which(ifeither) is the good for us humanbeings?

Despite the fact that the dramatic scene-setting of the Philebus is spare by comparison with other Socratic dialogues, its protagonists Socrates and Protarchus are drawn richly enough for us to see that somethingis at stake for them in the comparative question. This is not the pursuit of knowledge for knowledge s sake alone. So perhaps we can clarify the nature of the project of the Philebus if we can understand why answering the comparative question is practically relevant.

It is tempting to assumethat the question is practically relevant insofar as the answertoitmakesadifferencetodeliberation. Thismightbespelledoutinseveral ways. One possibility, familiar to us, though with no obvious textual support, is

So, though divine intelligencemayavoid thecriticismsleveledagainsthumanintelligence,thatis irrelevant to their project (22c).

18 See Meyer (Chapter4) and Harte (Chapter 15) for discussion of these problems. Their debate focuses in particular on how to understand theidea ofbeing responsible for the mixedlife.

that knowledge of comparative value matters for calculating the optimal choice. Related to this, and with at least some grounding in the text, is that answeringthe comparative question mighthelp us determinewhether anyamountofpleasureis worth the loss of knowledge (63d-64a). ? Somewhat differently, if second prize goes to the cause ofthe mixedlife, perhaps the idea is that we cannotattain the good for humanbeings if we lack the power to produce the life in which it resides, in which case perhaps the comparative question is important because the answer to it indicates the first step we should take in pursuing the human good, viz. acquire the power ofproducinga life with the right mix ofpleasure and wisdom.

Platomayinfactacceptallthesedeliberativeprinciples. Buttheissue iswhether discovering deliberative principles or pragmatic strategies is hispoint in arguing for the superiority of wisdom to pleasure. We would like to suggest that his framing the discussion in termsofathletic competition and prize-giving suggests otherwise. Consider, for example, Protarchus view of what is at stake in the question about silver. Socrates says that he would go to the mat to deprive pleasure of second prize, even more than to deprive her offirst (22c-e); Protarchus concurs in this estimate oftherelative stakes, explaining that although,as things now stand, pleasure has taken a fall (she was competing for the victor s crown),still, were she to be deprived ofsecondprize too, she wouldbe downright disgraced in the eyes of her lovers (dv tiva Kai druysiav oxoin mpos THY adbris épaora@v), and that because she would no longer appear so beautiful, not even to them (od8 yap éxeivois é7 Gv époiws paivorro Kady) (22e-23a). In saying this, Protarchus implies that the point of settling the comparative question is not so much to discover deliberative principles as simply to ensure, for its own sake, appropriate honor (or, if Socrates is right, dishonor) to pleasure. Although Socrates is not so explicit, securing honor for wisdom seemsto be his goal as well. In hisdiscussion ofthe forms ofknowledge, forexample, hesuggeststhathis purpose is to correct our view of which intellectual accomplishments are the noblest (kallista), so as to justify assigning the names reason (nous) and wisdom (phronésis)\ names appropriate to the noblest things (kallista) because they are names most worthy of honor (a y &v tis Tysjoere uddiora évéuara) to dialectic rather than rhetoric (59b-d). Despite its alleged usefulness, rhetoric is an inferior form ofreason.

This might be an implication of Jones s interpretation of 61c-64b according to which pure knowledge is shown tobeinvariablygood,whilepleasure is goodonlyontheconditionofthepresence ofknowledge(see this volume, Chapter 14).

2° Thismightbe an implication ofMeyer sviewthat secondprize goesto the item thatbringsabout themixtureofknowledgeandpleasure (seeChapter4). Amorecomplicatedversionofsuchanaccount mightalsobebuiltuponthebasis ofHarte s interpretation ofthe final rankingasa rankingofdifferent kindsofcause(seeChapter 15). Evenifneitherknowledgenorpleasureis theverybestgood,iftheyare causally responsible for the happylife to varying degrees andin different ways, that is presumably something a wise deliberator should know.

Notice that both Socrates and Protarchus associate the superiority question with the question ofwhich contenderappearsto be and intruth is kalon. Kalon is a word that can refer to physical beauty, but also to a more spiritual splendor (for which reason it is often translated as noble or fine ).?? We might say that thekalon isexcellencemanifest: itdeserveshonor andpraisebecauseit is excellent andit elicits honor and praise becauseits excellence is manifest. The point ofan athletic competition orbeautycontest is to revealthe victors superiority, to make theirexcellence manifest;beingexcellence,when revealeditwillshine,andthereby attract toitselfin facttheadmiration andpraisethatitjustlydeserves. Put another way, thepoint ofsuch acontest istoputthecontestantson display, in competitive performance, so that the superior excellence of the winners may be revealed, definitively, not primarily by a final calculation or tally, computed afterwards by an impartial and dispassionate scorekeeper, but first and foremost by the performanceitself, which is sufficient in its own right, not merely to warrant, but positively to draw to the victors the honor and reverence that their excellence deserves. So understood, there is no expectation that answering the superiority question will make any immediate difference (say) to our deliberations, beyond the decision to give honor whereit s due.

Oursuggestion, then, is that the point ofdiscussing the superiority question is notprimarilyto decide but more importantlytoshowwhichisbetter andwhich is worse, both positively revealing the superior excellence of reason, i.e., making her appear beautiful or noble (kalon), and also and not least exposing the inferiority of pleasure, revealing how much of her apparent beauty is merely apparent, inasmuch as so much ofher is accompanied by, or even united with, unreality, ugliness, and pain. Read this way, it wouldbe a mistaketo thinkthat

71 Aristotle goes so far as to define the kalon as whateveris praiseworthy[orpraised] becauseitis worth choosing foritself, or whateveris pleasant becauseit is good (Rhetoric 1366a33-34), but Plato manifests a similar assumption about the intrinsic connection between the kalon and praise in the Philebus: It is mostjust to assign names concerning the noblest (kallista) sorts ofthing to the noblest (kallista) things and nous and phronésis are names one should especially honor (59c-d), the implication being that, in being names one should especially honor, these are the noblest names.

22 AsWarrendiscussesinhis contribution to thisvolume (Chapter11), thePhilebuscontainsseveral remarks about good or proportionate mixture as the metaphysical basis for the kalon. Things that are beautiful by themselves are one source ofpure pleasure.

?° This interpretation was suggested to us by Broadie (2007, 154-7). However, whereas Broadie s ultimatepointis (in rather Aristotelian spirit) to criticize Plato forapproachingthehuman goodas an object ofcontemplation rather than as an objectofpractical reason andaction, we believe his moral psychology supports this approach aspractical.

24 As Dimasarguesin his contribution to this volume (Chapter8), the falseness offalse anticipatory pleasure is not so much anysort offalse content pleasures mayhave butrather, in particular, the false conception, typical ofan intemperate, vicious person, ofwhat healthy equilibirium amountsto. Likewise, when Socrates moves on to discussing the false pleasures arising from the juxtaposition of pleasure, pain, and neutral state and the false mixed pleasures, his point is not simply to reveal an illusoryaspectoftheseexperiences,but to unmaskthe most intenseand apparently desirablepleasures as entirely unwholesome. (As Pearson shows in his careful reconstruction of this portion of the dialogue (Chapter9), this is the point of Socrates appeal to those stroppy characters whoinsist that pleasure is really just release from pain.) Socrates indictment culminatesin the especially bitter

the object of such an enterprise is purely theoretical, aimed at producing an impersonal and disinterested contemplation and appreciation. On the contrary, a competition thatputsthe respectivemeritsofpleasureandwisdomondisplay, thereby making them manifest, will immediately involve and engage a variety of affective attitudes admiration and longing, contempt and disgust of intense and insistent (though perhaps indeterminate) practical relevance. It is true that the idea of a contest for second prize may strike us as strange, given the prominence of calculation, of deliberation and decision, in contemporary moral philosophy. But though reason (of course) is also a central category of Plato sethics, itwouldbeamistake, inhisview, tothinkwecantreatofitsvirtues, or win it admiration andtrust, in isolation from character, which grows from processesofemulation andreachesmaturity (orsoitmightbeargued) inakindof self-knowledge. Put anotherway,it s importanttoshowthatwisdomissuperiorto pleasure, because it is only if we can be brought to admire wisdom that her aspirations and longings will ever become for us authoritative witnesses, so that we become the kind of people for whom deliberation and reasoning are decisive for living well.

Ifthe disagreement between partisans ofpleasure and philosophy is in part a disagreement about what to honor and admire, then we can understand whyit would be importantto clarify the ranking ofgoods below first prize. Since lower goodsfindtheir place in the rankingin accordance with theirdegree ofkinship to thebest, a mistake aboutthe comparativevalue oflower goods impliesa failure to appreciate the value of the best good. People may nominally agree about what deservesfirst place but, through disagreements about the ordering ofsecond and third places, reveal that they were appreciating the first place winner in quite different ways.

Now,Socrates and Protarchus do not knowwhatthe best goodis until the end ofthe dialogue, and not fully even then. Their investigation concerning second prize proceeds in ignorance ofwhat deservesfirst prize, as ifthey couldsettle the comparative question independently of answering the question about the best good. So Plato s project in depicting this conversation is unlikely to be that of revealing that hedonism involves an incorrect grasp ofthe best good. However, there is another, related reason it might be ofthe utmost importancetosettle the

account of the pleasure of malicious envy (or phthonos, a concept usefully clarified by Destrée in Chapter 10) which, according to Socrates, lies at the heart of the urbane and apparently harmless practice ofcomedy.

?5 See Barney (2010a)for the argumentthat Plato seeks to transform ourattitude towards the good from desire to appropriate to admiration. She points out that when teenagers develop a crush,their longing is often combined with confusion about what to do about it should they follow their crush around?Startwearingthesameclothesandlisteningtothe samemusic? Love desiresits objectwithout laying out a clear deliberative route.

comparative question: properly honoring things subordinate to the best good enables us to discover what the best good is. Precisely because there is a relation of kinship or likeness amongfirst and subsequent prize-winners, a person who answers the comparative question incorrectlywill from the outset be misoriented in the search for the human good.

3. The Logic ofExhibition

Wethinkthat understanding the project ofthe Philebus in this way, as a conversation aimed at altering Protarchus (and our) ethico-intellectual attitudes of honoring and admiration, also suggests a solution to the first problem weraised, concerning the apparent lack of argumentative motivation for the length and detail ofmany ofthe dialogue s discussions. In brief, we suggest that the logic of the Philebus as a wholeis the logic ofan exhibition in speech ofpleasure and reason. * Although thediscussionsofthe divine method, cosmic nous, pleasure, and wisdom are more intricate than is strictly required by any subsequent argumentSocratesexplicitlymakes,theirlengthisentirelyappropriate formaking the nature ofthe two contenders manifest in a way that immediately alters our attitudes ofadmiration andtrust.

To see that this is so, let us recall a final curious feature of the dialogue s structure. Earlier, we pointed out that Socrates seems to say more than his subsequent argumentsstrictly require and that it is unclear precisely how earlier momentsrelate logicallytohis ultimate conclusions. Notethat one reasonforthis unclarity is that the crucial persuasive cruxes of the dialogue centrally turn on Protarchus intuition. For example, the identification ofthe goodis establishedby combining pleasure and knowledge into a well-mixed life in the hopes that the good will be more evident (phaneroteron) in such a mixture (61b). Indeed,it turns out thatit s not difficult to see (idein) that measure orproportion, beauty, and truth are the cause of the goodness of the mixture (64d-65a). This is not a conclusion which Socrates derives from reasonshearticulates; rather (so Plato presents it) it is a truth ofwhich Protarchus and Socrates are immediately aware (phaneroteron), once they have gone through the process ofmixing pleasure and knowledge into a desirable life. Their previous discussion about mixing seems to have put them in an epistemic position from which the nature of the good manifests itself to their reflection. But notice that Protarchus is able to occupy this position only because he has in a way that Plato stages quite literally trusted the testimony ofknowledge as it gave voice to its desire not to admit all

?6 Cf. Statesman 277c for the idea that logoi are the medium appropriate for exhibiting (déloun) living creatures andtheirvirtues.