Authors’Notes

Thislookslikeaboringbook.Iwouldonlyreaditforthepictures —LinneaSalkeld,top-notchperson

Inaway,thisisatextbookwrittenbyus— nowcurmudgeonswithPhDsandcumulative decadesofexperience,successes,mistakes,and misunderstandings—forourformerselves,when weknewlittleaboutdiseaseecologyandepidemiologybutwerekeentolearn.Theresultantbookwill nowhopefullyworkforstudentsasanintroduction tothescienceofemerginginfectiousdiseases,from outbreakepidemiologytoecosystemimpacts.

Thoughallthreeofushailfromnorthernclimes, wehaveattemptedtoincludeadiversityof zoonosesandwildlifediseasefromacrosstheglobe. Wedidourbesttomakesurethateverythingthat weincludedinthisbookwasaccurate,butwe includedresearchoncasestudiesthatarerelatively new,orpoorlystudied,orstudiedsooftenthatit wouldbeimpossibleforustoreadeverythingabout them.So,wewillhavemademistakes.Youmayalso noticeglaringomissions—andsoweencourageyou tousethisbookasamotivationtolearnandresearch more.Attheveryleast,wehopethatyoufindthe bookinteresting,clear,andnicetolookat.

Wewrotethisbookduringchallengingtimes,and wewouldnothavefinisheditwithoutthesupport ofourfamiliesandfriends.Ifnotfortheirguidance, therewouldbefewergoodjokesinthisbook.Truly, westolesomeofthem.

Wewouldliketothanka(parasitic)hostofscientificexperts,colleagues,andfriendsforsharingtheirexpertise.Whenacknowledgingsomeone

byname,thereisnoimplicitimplicationthatthe personendorsesorapprovesofthisbook.Most likelytheywillbeoblivioustoitsexistence,and dubiousofitscontent.Nonetheless,thankyouto MikeAntolin,APOPOandtheirHeroRATs,Tomas Aragon,CarolBoggs,DanielleButtke,ScottCarver, DaveCivitello,ChristopherCleveland,Meggan Craft,PaulCross,JakeDeBow,GiulioDeLeo, TerenceFarrell,MattFerrari,BrianFoy,Lynne Gaffikin,TonyGoldberg,GabeHamer,Madison Harman,CarlHerzog,RichardHoffman,James HollandJones,AnneKjemtrup,KevinLafferty,Bob Lane,EdwardS.Lino,AndreaLund,ParagMahale, AlynnMartin,StephenSchneider,PaulStapp,Jean Tsao,andJ.D.Willson.

WeareespeciallygratefultoHannaKiryluk,who madesomanyfigures,wrangledreferencelists,and confirmedthatcontentwasunderstandable.

Wearealsothrilledthatsomanypeopleshared theirstunningphotos,data,andgraphics.Thank you!

AtOUP,thankyoutoIanShermanforinstigating andinvestinginthisbook.ThankyoutoBethany Kershaw,whoseoriginalresponsetoChapter 1 helpedsetthetonefortherestofthebook(though wetheauthorsaccepttheblame).ToCharlesBath forpatientlyencouragingrichcontentandavoiding anymentionofdeadlineswhilstonUKlockdown. AndtoKatieLakinaforshepherdingusthroughthe finalstages.

DanSalkeldwouldliketothankhisbelovedparents;awonderful,scenic-road-takingVirginianredhead;twobrilliantgirlswho’vealreadyrackedup milesofexperttick-collecting;andthemuch-missed NateNieto.Andalso,whisperit,thankyouSkylar andDave;afterfifteenchaptersIstillthinkthat you’refunnyandinteresting.

S.HopkinswouldliketothankCarrottheDog forloudlyvoicinghisopinionsduringeveryZoom meetingandStuartRobertsonforprovidingartistic feedbackandhelpingtotranslateBritishco-author communications.

DaveHaymanwouldliketothankhistwocoauthorsfordoingmostofthework,beingexceptionallypatient,andhumouringhim.Heshould probablyalsothankhisfamily,buttheywillnever

readthis,andpossiblyhisteam,buttheywillalso probablyneverreadthis.Hewouldliketothank anyonewhodoesactuallyreadit.

Aquickmentionofstylisticoddities.Wehave deliberatelytriedtorestrainouruseofcitationsto letthewritingflowasmuchaspossible—references mightonlybecitedoncewithinanentireparagraph. Latinnameshavebeenrepeatedinfull,insteadof abbreviatingthegenusname,forreadabilityandto helplodgetheminthereader’sbrain.Likeanerrant Umingmakstrongylus.

Withallthatinmind,youmaynowturnthepage, andstartlearningaboutsomeofthegreatestchallengesofourtime:emergingzoonosesandwildlife pathogens.

3.3Interpretingepidemiccurvepatterns

3.8Testvalidity,within-hostpathogendynamics,andtesttype

3.9Testvalidityandlocalpathogenprevalence

3.10Testvalidityandrepeattests

5.9Whendopathogensdrivehostspeciestoextinction?

5.10Predictinglong-termdynamicswhileignoringrandomchance

5.11Incorporatingrandomchancewhenpredictinglong-termdynamics

6.4Faecesasanenvironmentalreservoir

7.1Introduction

7.2Spilloverfromasinglehostreservoir:armadillosandleprosy

7.3Multiplereservoirhosts:rabies,dogs,andwildlife

7.4Interactionsbetweendomesticandwildlifereservoirs

7.5Spilloverfrommultiplereservoirs:Lymedisease

7.8Idiosyncrasiesofhumanbehaviourandexposuretotick-bornepathogens

7.9Contributionsofnon-reservoirhoststolocaldiseaseecology

8.5FindingthereservoirforHantavirusPulmonarySyndrome

9.2Traveldrivesstutteringoutbreaksinnon-endemicareas

10.4Extremeweatherevents

12.2Smallcarnivorepopulationsthreatenedbypathogensfrom domesticdogreservoirs

12.3Smallcarnivorepopulationsthreatenedbypathogensfrom wildlifereservoirs

12.4Environmentalreservoirsandresistantreservoirhostsdrive amphibianspeciestoextinction

13.1Communitiesandecosystems

13.3Top-downeffects:mesopredatorrelease

13.4Top-downeffects:trophiccascades

13.5Parasitesinfoodwebs

14.1Treatinginfectedwildlife:ataleofscabidwombats

14.2Vectorcontrolandvaccination:conservingtheplagued black-footedferret

14.4Cullingwildlifetopreventwildlife–livestockdisease transmission:thecaseofbadgersandbovinetuberculosis

14.5Cullingandwildlifediseasereservoirs,moregenerally

14.6Unintendedconsequences—bison,elk,cattle,andbrucellosis

15.1Rapidemergenceofanovelpathogen

15.2Fromoutbreaktopandemic

15.3ThesourceofSARS-CoV-2spillover

15.4Controllingthespreadofapandemicvirus ornot

15.6Complexityandwickedproblems

Spilloverandemerginginfectious diseases

Lambcastrationisnotalwaystheidyllicpastimethatsomepeoplemaythinkitis.

—MarcAbrahams

1.1 Introduction

Wyoming,USA,June2011—Inaworldthatisincreasinglyurbanized,andwherefarmingispractisedby fewerandfewerpeople,youmaynotbefamiliar withanyofthetime-honouredtechniquesusedto castratelambs.Awebsearchwillsuggestthatyou canuseyourteeth,andthatthishastheadvantage ofreducingthelikelihoodofaconsequentinfection inthenewlyemasculatedlamb.However,thereare risksforthecastrator.

Atamultidayeventtocastrateanddockthetails of1600lambsonaWyomingsheepranch,twomen usedtheirteethtocastratesomeofthelambs.Ten otherpeopledidnotadoptthistechnique.Subsequently,thetwomenwerestrickenbydiarrhoea, andonealsosufferedabdominalcramps,fever, nausea,andvomiting.Onepatientwashospitalized foraday,butbothmenrecoveredfromtheirbouts ofillness(VanHoutenetal.2011).

TheWyomingDepartmentofHealthinvestigatedthesecasesandmanagedtoisolateindistinguishablebacteria—Campylobacterjejuni—from bothmen’sstoolsamples.Although Campylobacter causesanestimated1.5millionillnesseseachyear intheUnitedStates,the Campylobacterjejuni strain identifiedintheWyomingshepherdswasextremely rare(8from8817strains),suggestingacommon sourceofinfection.Thesourceturnedouttobethe lambs,someofwhichwereexperiencingtheirown boutsofdiarrhoea.

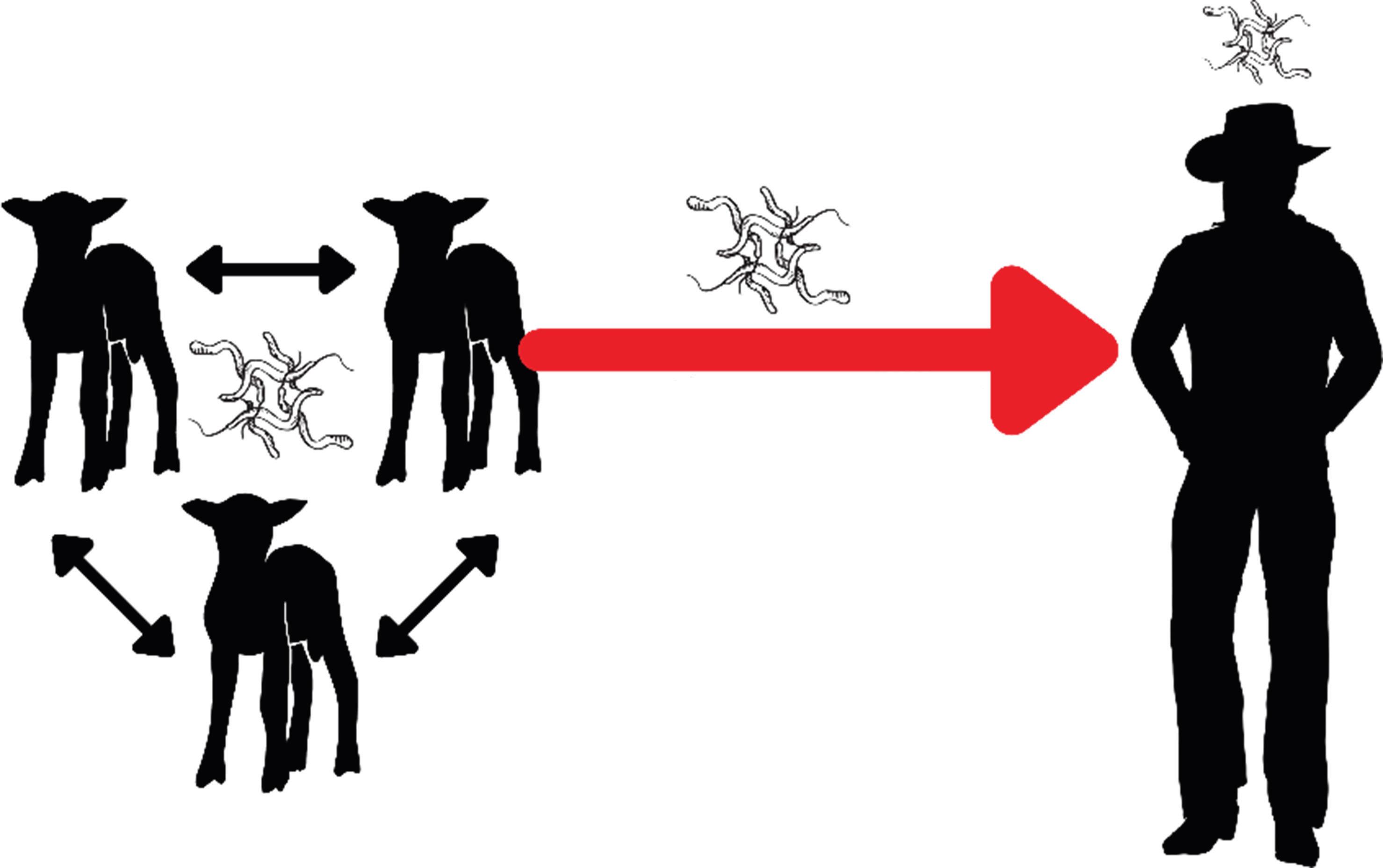

Thisisamildlyamusingcaseofa zoonosis apathogentransmittedfromnon-humananimals tohumans (Fig. 1.1). Campylobacterjejuni wascirculatinginthesheepflockandtheunusualcontactbetweenlambscrotumandhumanteethand mouthsenabledzoonoticdiseasetransmission.

Itcouldalsobeconsideredanexampleofan emerginginfectiousdisease (EID)—causedbya pathogenspreadingtonewspecies,spreadingto newgeographicareasandpopulations,orspreadingatfasterratesinplacesorpopulationswhere ithaspreviouslybeenendemic (Jonesetal.2008). Inthiscase, Campylobacterjejuni appearedtohave enteredthelocalhumanpopulation(Wyoming shepherds)forthefirsttime.

Scientistspridethemselvesonbeingobjectiveandsystematic,butwhenit’syouwithanarachnidinyournasal cavity,thatsenseofdistancegoesrightoutofthewindow.Whenyoufirstrealizeyouhaveatickupyournose, ittakesallyourwillpowernottoclawyourfaceoff.

—TonyGoldberg

Kibale,UgandaandWisconsin,USA,June2012 Exposuretowildlifezoonosesand/ortheirvectors isnotanunusualcircumstanceaffectingonlylucklessshepherds.InJune2012,DrGoldberg,aveterinaryepidemiologistwitharesearchbackground inprimatologyandemerginginfectiousdiseases, reluctantlyacknowledgedaseverepaininhisnose (Goldberg2013).Severaldayspreviously,Goldberg

CreatedbyHannaD.KirylukusingCanva.com.

hadbeeninatropicalforestinKibale,Uganda, studyinghowanthropogenicchangestoecosystemsalterhealth-relatedoutcomesandinfectious diseasedynamicsinpeople,wildlife,anddomestic animals.NowbackathisWisconsinhome,Goldbergusedanangledmirrortoexaminehisnostril, andconfirmedhissuspicionsbyseeingthe‘smooth, roundedbacksideofafullyengorgedtick’.While rare,these‘nostrilticks’arenotunheardofinvisitorstoKibaleNationalPark.ThiswasDrGoldberg’s thirdinfestation(andyethekeptreturning!).Fortunately,hesufferednolastingharm,besidesthe mentaltraumaofhavingablood-suckingarachnid insidehisnose.

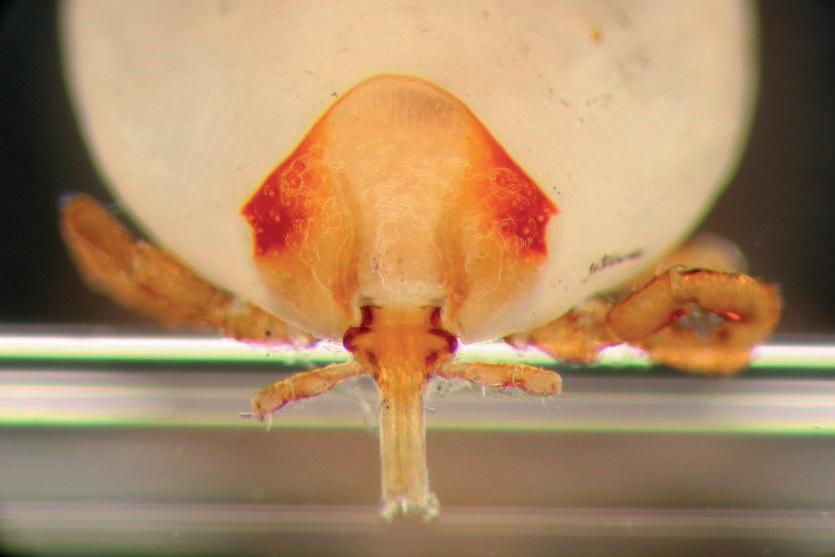

Collaboratingwithmedicalentomologistsand primatologists,Goldbergandcolleagueswereable todescribethistickaslikelyanew Amblyomma species(Fig. 1.2).Usinghighresolution photographsofchimpanzeenoses(Fig. 1.2),they showedthatroughly20%ofyoungchimpanzees hadtick-infestednostrils(Hameretal.2013).Presumably,theticksinfestthenostrilbecausechimpanzeeslovetogroomeachother,soticksneed aplacetohidefromchimps’stubbyfingers.FurtherresearchsuggeststhatsporadiccasesofnostriltickshaveoccurredinpeoplevisitingAfrica’s equatorialforestsforseveraldecades.Canthenostriltickstransmitpathogens,andcouldunwary

travellersinadvertentlycarrydiseaseagentsfrom tropicalAfricatotheirfar-flunghomes?Thatquestionremainsunanswered.

Thisincidenthasseveralpertinentlessons.First, human–wildlifeinteractionsoccuratindividual levels,andoftengounrecognized.Second,although contactisatanindividuallevel,theimpactsare nolongerlimitedtosmallgeographicallocales. Airtravelmeansthatpathogensandvectorsnow haveopportunitiestotravelgloballyandwithin infectiousperiods(Chapter9).Third,human–wildlifeinteractionshavenotalwaysbeenassiduouslydescribedorcatalogued. Amblyomma ticks haveprobablybeenexploringprimatenostrilsfor alongtime,butittookthechanceinfestationofa qualifiedveterinariantoresultinitsscientificidentificationandfurtherresearch.

1.2 Fromspillovertopandemic

Spilloverevents—theoccasionswhenapathogen jumpstonewspeciesandtherebyinfectshumans (zoonotic)oranimalsthatarenottheusualhost species—occuratthescaleoftheindividual,but theimpactsofpathogensinanewhostspecies areunpredictable.DrGoldbergdidnotreportany pathogentransmissionafterbeingbittenbyan African Amblyomma tick—perhapsbecausethetick

zoonotic transmission

Figure1.1 Zoonotic(non-humananimaltohuman)transmissionof Campylobacterjejuni fromWyominglambstohumans.

Figure1.2 A,B,C.Nostriltick, Amblyomma,extractedby,andfromthenostrilof,TonyGoldberginWisconsin,USA,aftertravelsinKibale NationalPark,Uganda.PhotosbyGabrielL.Hamer.D.Nostriltickinayoungchimpanzee,Thatcher,inKibaleNationalPark,Uganda,2012.Photo byAndrewB.Bernard/KibaleChimpanzeeProject.

Originallypublishedin Hameretal.(2013).CoincidenttickinfestationsinthenostrilsofwildchimpanzeesandahumaninUganda.AmericanJournalofTropical MedicineandHygiene,89,924–7.UsedwiththepermissionofAmericanJournalofTropicalMedicineandHygiene.

wasnotcarryingapotentiallypathogenicinfection, orbecauseanypotentialpathogenitcarriedwas notabletoinfectahumanhost,orwasunableto infectDrGoldberginparticularbecausehewasnot susceptible (see Chapter2).Thebacteriuminfecting shepherdsinWyomingdidcauseillness,butasfar asweknow,therewasnosubsequenttransmission fromthosetwohumancasestootherhumansor lambs.

Termstodescribeadisease’simpactincludeclusters,outbreaks,epidemicsandpandemics.

• A cluster isan observationofanabove-normal numberofcases,normallyaggregatedintime atalocalscale.Oftenthisissimplythetermfor thebeginningofanoutbreak,butbeforeconnectionsandtransmissionchainshavebeenofficially identified.

• An outbreak or epidemic (alsocalledan epizootic whenreferringtowildlifeordomesticanimaldisease)isan increaseofdiseasecases,often withcontinuedtransmissionandwithestablishedcausativelinksbetweencases.

• A pandemic isan outbreak/epidemicatthe internationalorglobalscale

Thesedescriptionsblurandbleedintoeachother; thereisnotnormallyanofficialthresholdforwhen aclusterbecomesanoutbreak,orforwhenanepidemicbecomesapandemic.

Howdoesonedefinean‘above-normalnumberofcases?’Thenormalnumberofcasesrefers toobservedbaselineinfectionratesofapersistent pathogeninapopulationorcommunity.Thisis referredtoasthe endemic levelofthedisease(called enzootic whenreferringtowildlifeordomestic

(d)

Box1.1Ondefinitions

...

Ihatedefinitions.

—BenjaminDisraeli,BritishPrimeMinister (1804–1881)

Definitionscanbehelpfulforestablishingcommonunderstanding(ormisunderstanding).Thisbecomesespeciallyimportantduringmultidisciplinaryconversations.For example,theabbreviationEBMsignifiesEcosystem-Based Management,ExpressedBreastMilk,orEvidence-Based Medicine,dependingonwhetheryouareaconservationist,apaediatricnurse,oraphysician.Definingyourterms isalwaysuseful.

However,definitionsmaynotbeeasilyachievable.For example,in1964,theUSSupremeCourtJusticePotter Stewartargued‘Ishallnottodayattemptfurthertodefine thekindsofmaterialIunderstandtobeembracedwithin thatshorthanddescription[‘hard-corepornography’],and perhapsIcouldneversucceedinintelligiblydoingso.But IknowitwhenIseeit ’.Wecouldn’tagreemore. Forexample,wehavedefined zoonosis asapathogen transmittedfromnon-humananimalstohumans.Other definitionssuggest‘apathogentransmittedfromanimals tohumans’;theyneglect‘non-human’.Ifyouconsider humanstobeanimals,thenthisdefinitionwouldencompasssyphilisandgonorrhoea—notourintention!Even ouradopteddefinitionhassomeissues.Typically,malaria causedby Plasmodiumfalciparum isnotconsidereda zoonosis,becauseitpossessesahuman-mosquito-human lifecycle.Butisn’tamosquitoananimal?Slipperyslopes becomeabundantasoneargueswhat kind ofanimal constitutesananimal.

Wesuggestthatthereaderdoesn’tbecomebogged downbydefinitions.Adoptthemiftheyareuseful,adapt themiftheyarenot,andbeforgiving!

animaldisease)(Box 1.1).Wheretransmissionina populationispersistentandatrelativelyhighlevels, thediseasepatterncanbereferredtoas hyperendemic.Incontrast,diseasesthatoccurinfrequently andirregularlyareoftentermed sporadic.

1.3 Zoonoses

Zoonoticpathogentransmissioncanbeclassifieddependinguponthetransmissionpatterns inhumanpopulations(Wolfeetal.2007, LloydSmithetal.2009, Woolhouseetal.2013).(Similar

classificationscanbeusedforanyinfectionentering anynewhostspecies,suchasgiraffesornewts insteadofhumans.)Importantly,pathogenscould fallintodifferentcategoriesindifferentcontexts.

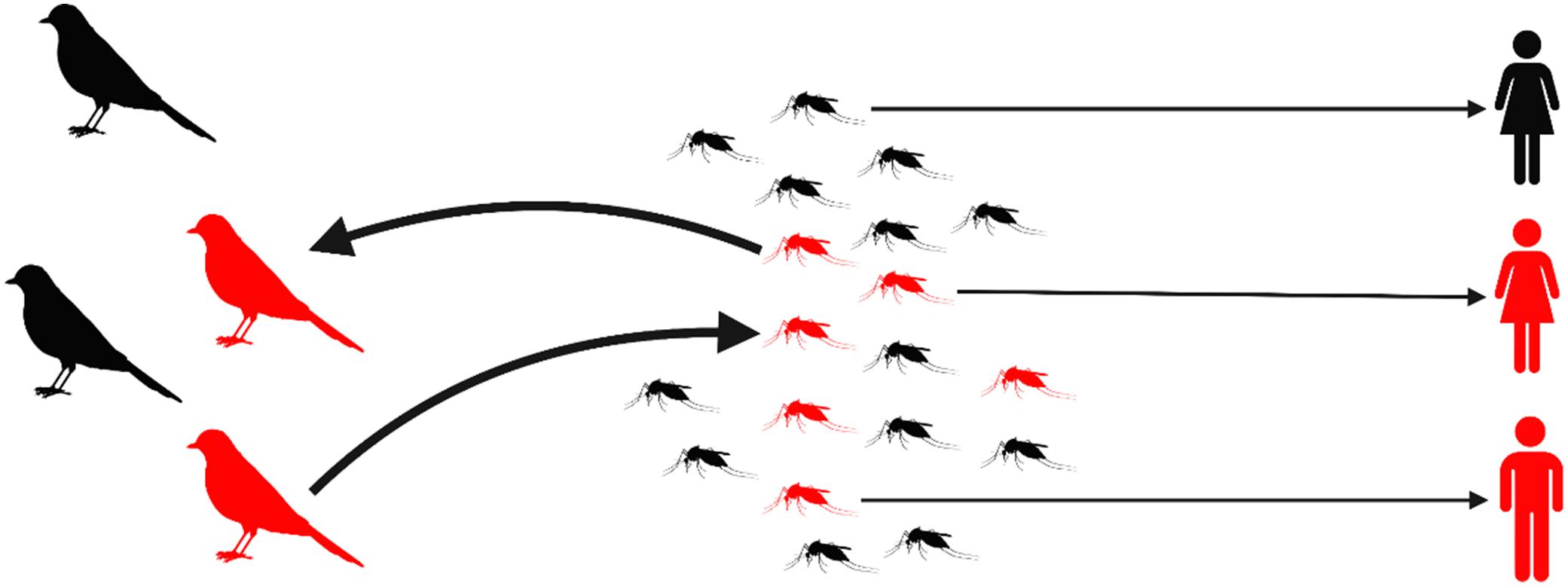

Dead-endzoonoses canbetransmittedfromanimalstohumans,butdonotsubsequentlyspread fromhuman-to-human.Forexample,WestNile viruscirculatesintheUSinbirdsandmosquitoes andcancauseillnessinpeopleafteramosquito bite.However,human-to-humantransmissiondoes notoccur(Fig. 1.3).(Althoughinfectionsacquired frombloodtransfusionsarepossible(Iwamotoetal. 2003),bloodcollectionagenciesscreendonated bloodforWestNilevirus.)Anotherdead-end zoonosisisrabiesvirus,whichistransmittedto peoplethroughbitesofrabidwildlifeordomestic species.Despitebeingvaccine-preventable,rabies killsapproximately59,000peopleeveryyear(the equivalentofonepersoneverynineminutes),40% ofwhomarechildrenlivinginAsiaandAfrica. Humansarecapableofsheddingrabiesvirusduringtheclinicalphaseofdiseasebuttherehasnot beenadocumentedcaseofhuman-to-humantransmission,exceptfromunusualcasesinvolvingorgan ortissuetransplantation(Blackburnetal.2022, Chapter2).

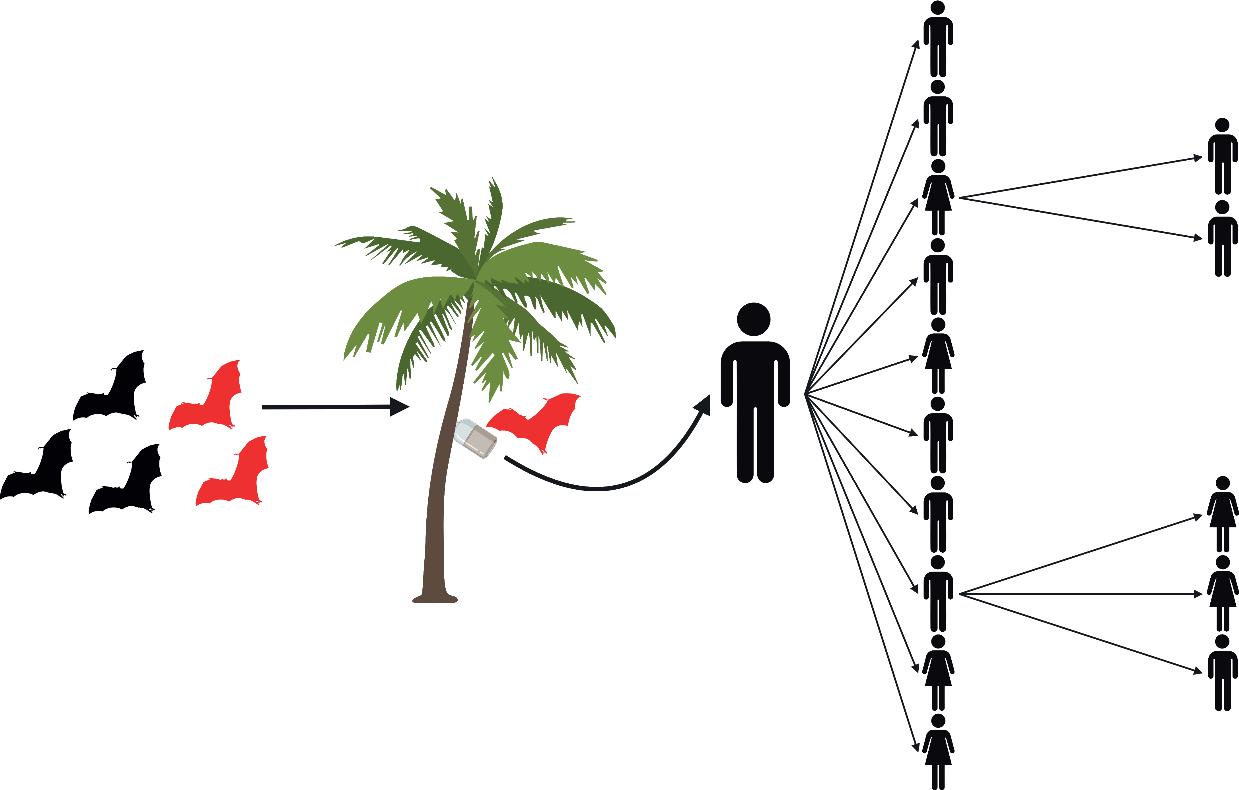

Stutteringzoonoses canjumpfromanimalsinto humans,andthen,withsomelimitedsuccess,into otherpeople.Intheseoutbreaks, human-to-human transmissionislimitedandthepathogen stutters or fadesout beforeafull-blownepidemicoccurs. Forexample,since2001,inBangladesh,therehave beenrecurrentspilloversofNipahvirustohumans fromIndianfruitbats(Pteropusmedius).Often,the spilloverresultsinanisolatedhumancase,but human-to-humantransmissioncaninfectamean of7persons(range1–22)resultinginastuttering outbreak(Lubyetal.2009)(Fig. 1.4).Inanother examplefromSouthTexas,USA,therearesuitablemosquitovectorsforZikavirus,butZikaoutbreaksinhumanshavetendedtofadeout,perhaps becausethemosquitoesarepredominantlybiting non-humanhosts(dogs,domesticanimals)(Olson etal.2020).

Sustainablezoonoses originateandpersistin animals, butonceinhumanpopulations,theycan spreadthroughhuman-to-humantransmissionto causeoutbreaksthatpersistthroughmultiple generationsoftransmissionandhumancohorts

Figure1.3 WestNilevirusistransmittedamongwildbirdsbymosquitoesintheUnitedStates.Infected(red)mosquitoesthatfeedonhumans maycauseazoonoticspilloverbyinfectingpeople(red),butthereisnofurthertransmissionfromperson-to-person;itisadead-endzoonosis.

CreatedbyHannaD.KirylukwithBioRender.com

Stuttering humanto-human transmission

Figure1.4 Stutteringzoonosesinvolvelimitedhuman-to-humantransmissionaftertheinitialzoonoticspilloverandendupfadingout.For example,inBangladesh,NipahviruspersistsinpopulationsofgreaterIndianfruitbats(Pteropusmedius)butoccasionallymakesthejumpinto humansthroughrawdatepalmsapcontaminatedbybatwaste.Theprimaryhumancasecantheninfectotherpeople.Astuttering human-to-humanNipahvirusoutbreakoccurredin2004,whentheindexpatientinfectedfourofthepeoplecaringforhim(hismother,son,aunt andaneighbour;theincubationperiodwas15–27days).Whilstinhospital,theauntwascaredforbyapopularlocalreligiousleader,who becameill13dayslater,andwasvisitedbymanyofhisrelativesandmembersofhisreligiouscommunityathishome.Twenty-twopeoplewere infectedaftercontactwiththereligiousleader.Furthertransmissionsoccurredand,intheend,thechainoftransmissioninvolvedfivegenerations andaffected34people(Lubyetal.2009).

CreatedbyHannaD.KirylukusingBioRender.comandasketchonanoldpizzabox.

Wildlife reservoir

Zoonotic spillover

Aclassicexampleofasustainablezoonosiswould beplague,causedbythebacterium Yersiniapestis, famousfortheBlackDeathinmedievalEurope. Inthemodernera, Yersiniapestis stillsporadically jumpsfromanimalpopulationsandsubsequently spreadsfromperson-to-person,e.g.in2017aplague outbreakoccurredinMadagascarwhenaman,presumablyinfectedfromananimalsource,travelled bytaxithroughthenation’scapital,Antananarivo, andtransmitted Yersiniapestis todozensofpeople.Person-to-persontransmissioncontinuedand

causedpneumonicdisease(infectionofthelungs), resultingin2348confirmed,probable,andsuspectedcases,including202deaths.

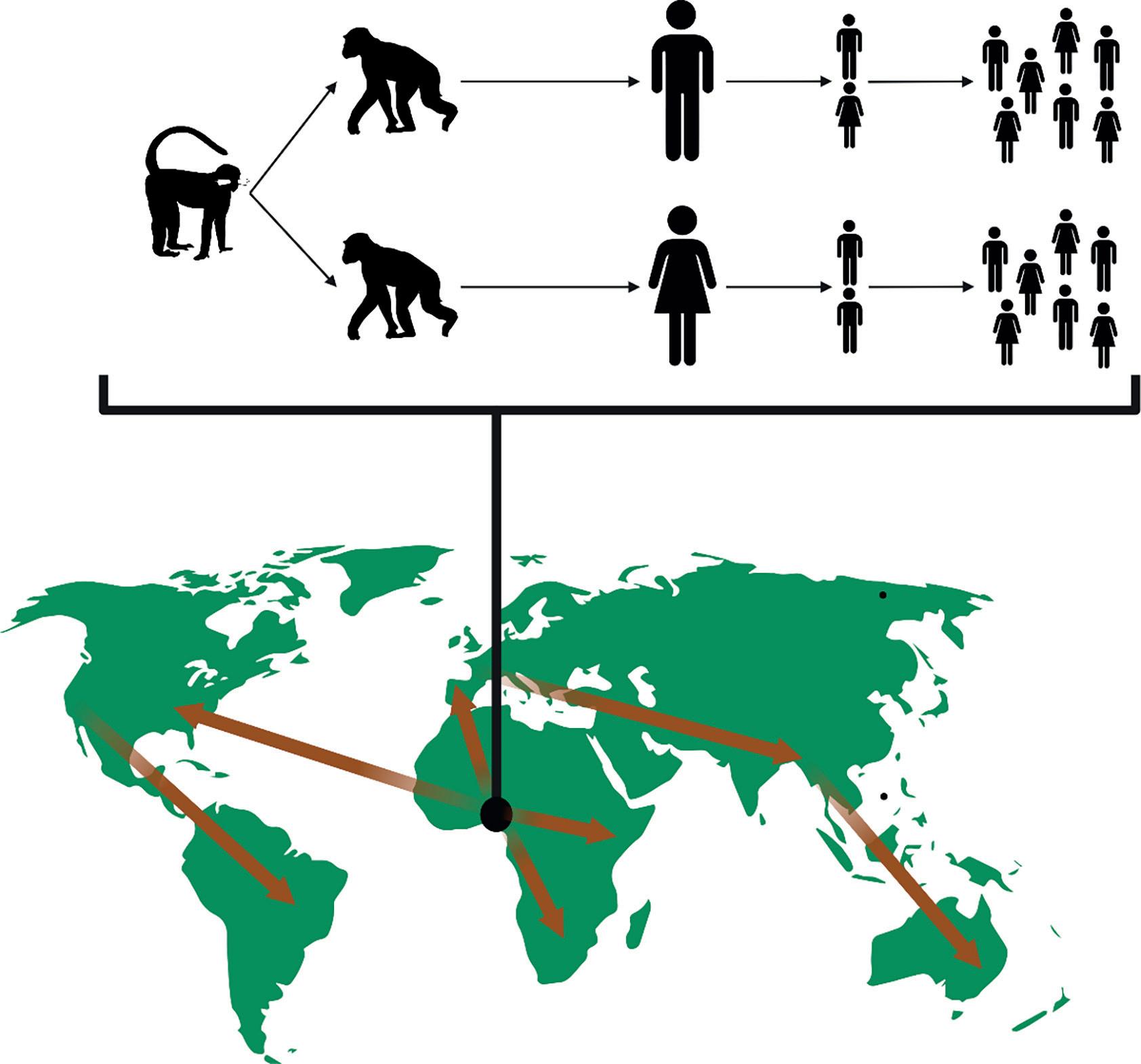

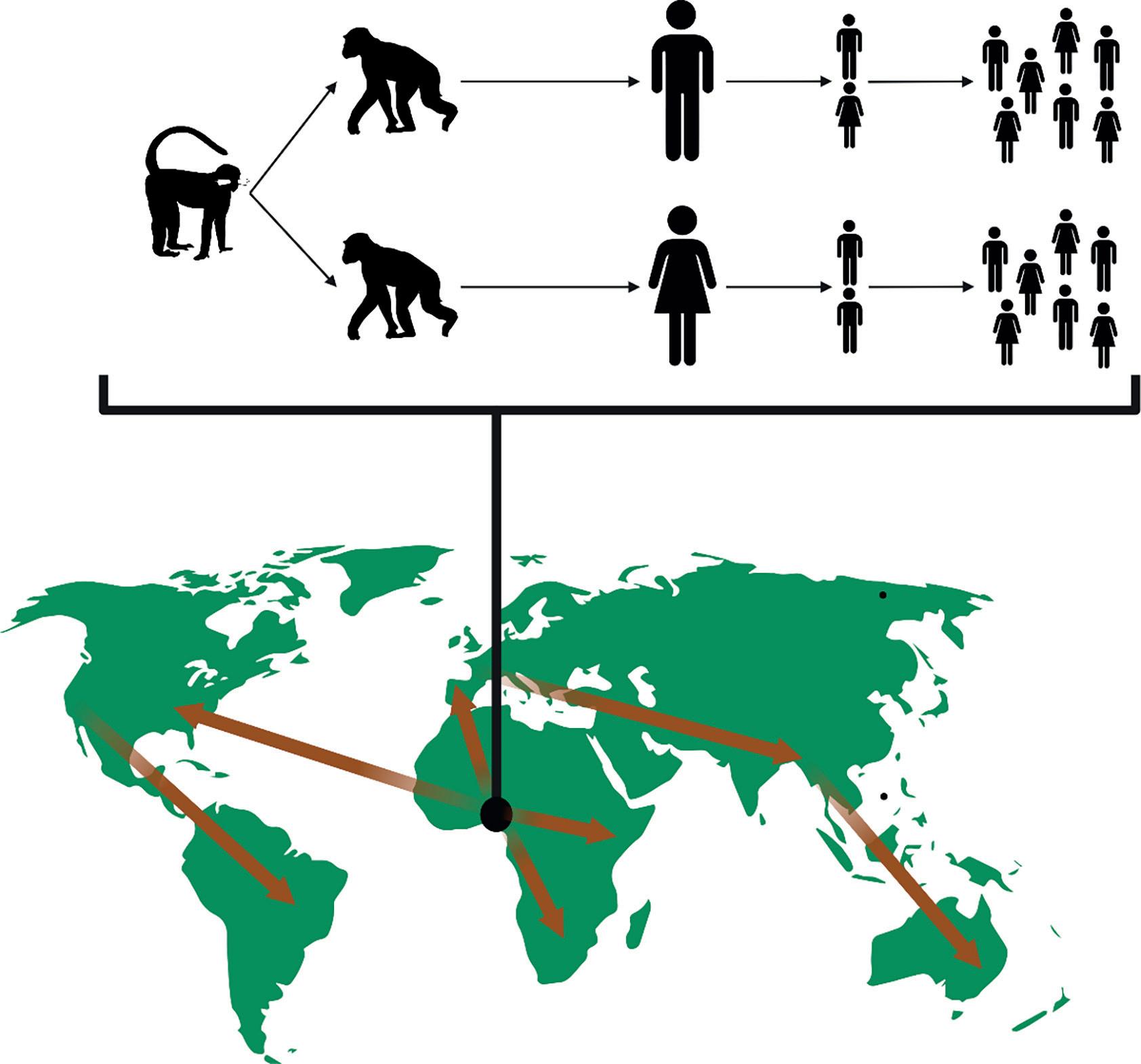

Sustainablezoonosesalsoincludepathogensnow regardedashumandiseases,buthistoricallyor evolutionarilythediseasehadazoonoticorigin, whetherthatwasfromdomesticatedanimals,livestock,orwildlife(Fig. 1.5).Recurrentintroduction fromanimaltohumanpopulationsisnolonger aconcern;thepathogensareadaptedtohuman transmission.Duringtheslowwritingofthisbook,

Figure1.5 Sustainablezoonosescanemergefromanimalhostsintohumanpopulations,possiblyviaa‘bridge’reservoirhost,andthenadaptto persistenttransmissionwithinhumans.Humantravelcanthenelevatethespilloverincidenttoanoutbreakandthentopandemictransmission.For example,humanimmunodeficiencyvirus-1(HIV-1)probablyjumpedfrommonkeypopulationstochimpanzeestohumans,andthechimpanzeeto-humanspilloveroccurredmorethanonce.Human-to-humantransmissionisnowresponsibleformaintainingthevirus,whichisnowpresent throughoutglobalpopulations(arrowssimplyrepresenttheconceptofglobaltravel).Similarly,SARS-CoV-2jumpedintohumanpopulationsin 2019andisnowasustainablepandemicpathogen. CreatedbyHannaD.KirylukwithBioRender.com.

Monkey (e.g. Cercocebus spp. or Cercopithecus spp.)

Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) x 1,000,000

SARS-CoV-2hasprovidedaprimeexampleofa novelvirus(sourcestillunknown)thathasspilled overintohumanpopulationsandcontinuedevolutionandcirculationinitsnewhumanhost (Chapter15).

1.4 Zoonoticoriginsofthe‘BigThree’

Malaria,tuberculosis,andAIDSareconsideredthe ‘BigThree’infectiousdiseases,withcatastrophic impactsuponhumanpopulations,especiallyin low-incomecountries(Rocheetal.2018).These threediseasesillustratevariedevolutionaryand zoonotichistories.

Humanmalariaiscausedbytheprotist Plasmodium,whichistransmittedbyfemale Anopheles mosquitoes.Estimatesofthepublichealthburden createdbymalariasufferfromhighuncertainty, butin2013,therewerebetween95millionand 284millionnewcasesglobally,incurring703,000–1,032,000deaths(Murrayetal.2014). Plasmodium falciparum isthedeadliestofthevariousmalariaprotozoa.Bysamplingfor Plasmodium infaecalsamples fromwildapesthatwerelivinginremoteforested areasawayfromhumans,researchersdiscovered that Plasmodiumfalciparum probablyoriginatedin gorillas.Thoughthetimingofthiseventinevolutionaryhistoryisunknown,thespillovertohuman populationsmayhavebeenasinglecross-species transmissionoccurrence(Liuetal.2010, Prugnolle etal.2011).Thereislittleevidencetosuggestthat therearerecurrentintroductionsofmalariafrom apestohumansinAfrica(Sundararamanetal.2013) (Fig. 1.6).

However,‘zoonotic’malariacasesof Plasmodium dooccur: Plasmodiumknowlesi typicallyinfectsmonkeysinsouth-eastAsiabutwasrecentlydiscovered asahumanpathogen(Singhetal.2004, Singhand Daneshvar2013, Rajaetal.2020).

isresponsibleforoveramilliondeathsayear (datafor2013; Murrayetal.2014).Thevirus jumpedfromnon-humanprimatestohumanpopulationsmultipletimes,andnowisfirmlyestablishedasahumanpathogen.Forexample,HIV-2 likelyemergedinhumanpopulationsfromasooty mangabey(Cercocebusatys)sometimeinthelatterhalfofthe20thcentury.Thisinterpretationis basedonthreepiecesofevidence:thecommon ancestor,simianimmunodeficiencyvirus(SIVsm), isprevalentinWestAfricanpopulationsofsooty mangabeys;HIV-2isendemicinWestAfrica;and thegenomesofSIVsm andHIV-2arecloselyrelated (Hirschetal.1989).HIV-1hasadifferentorigin,andphylogeneticstudiessuggestthatchimpanzeesinsouth-easternCameroonweretheoriginalreservoirsofatleasttwoHIV-1strains.These apepopulationsprobablyacquiredthevirusfrom red-cappedmangabeysor Cercopithecus speciesat atimewhenchimpanzeepopulationswereevolvingintosubspecies(Keeleetal.2006).Thespillover tohumanpopulationsprobablyoccurredearlyin the20thcentury(Keeleetal.2006, Worobeyetal. 2008).

Thesootymangabey(Cercocebusatys)isasmoky-gray creaturewithadarkfaceandhands,whiteeyebrows, andflaringwhitemuttonchops,notnearlysodecorative asmanymonkeysonthecontinentbutarrestinginits way,likeanelderlychimneysweepofdappertonsorial habits.

—DavidQuammen

Today,thehumanimmunodeficiencyvirus(HIV) thatcausesacquiredimmunodeficiencysyndrome (AIDS)infectsapproximately30millionpeopleand

Tuberculosis(TB)isoneoftheworld’sdeadliestinfectiousdiseases—theWorldHealthOrganization(WHO)estimatesthatthebacteriumkills betweentwoandthreemillionpeopleannually, 98%ofwhomliveinthedevelopingworld—even thoughacureisavailable(Arnold2007).Athirdof peopleinfectedwithHIVhaveTB,andtheevolutionofmultidrugresistanttuberculosis(MDRTB) strainsisagrowingpublichealthconcern.Tuberculosisisusuallycausedby Mycobacteriumtuberculosis, buttheWorldHealthOrganization(WHO)estimatesthat>10,000deathsweredueto‘bovine’TB globallyin2010(Olea-Popelkaetal.2017),whichis causedbytherelated Mycobacteriumbovis Mycobacteriumbovis hasabroadhostrangeincludingcattle, Europeanbadgers(Melesmeles),Australianbrushtailpossums(Trichosurusvulpecula),deer,andsoon (BritesandGagneux2015)(see Chapter14).Consequently,ithasbeenassumedthat Mycobacterium bovis wasancestralto Mycobacteriumtuberculosis, whichwouldmakehumanTB(Mycobacteriumtuberculosis)anotherexampleofasustainablezoonosis. However,geneticanalyseshavediscoveredthat certainhuman Mycobacteriumtuberculosis lineages areactuallymoreancestral(phylogeneticallymore

10 nt

n=2/20

n=3/2

n=109/43/6

n=2/3/1

n=1/2

n=2 n=11 n=2 n =2 n=3 n=3 n=3 n=3 n=4

n=115/210/47

n=2/1/1

n=3/1 n=2 n=4/1

n=45/5 n=4/4

n=1/5/4

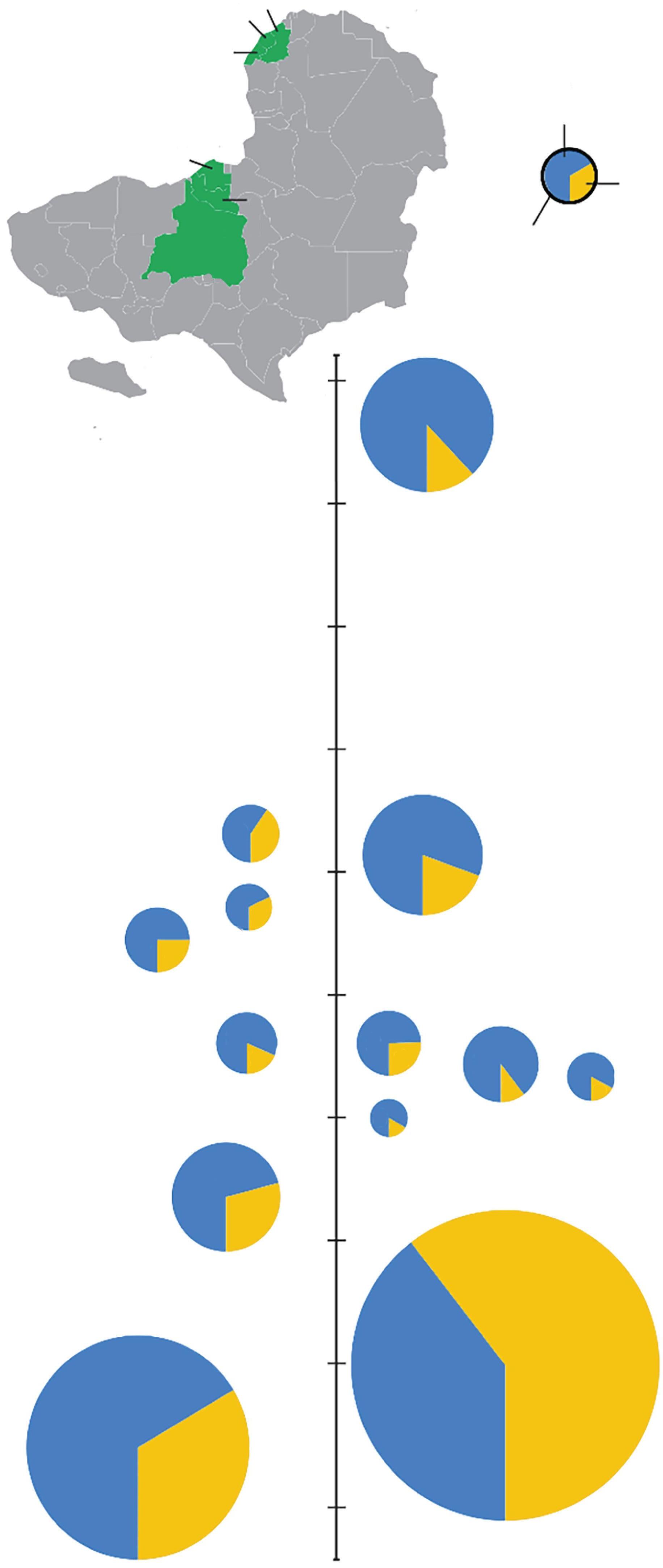

Figure1.6 Phylogenyof Plasmodiumfalciparum strainsfromruralCameroon. Plasmodiumfalciparum isthemosquito-bornediseaseagentthat causesfalciparummalaria.SequencesfromhumanslivinginCameroon(black)arecomparedtosequencesfromGenbank(white)andtheSanger Institute(grey), Plasmodiumpraefalciparum fromgorillas(green),and Plasmodiumreichenowi fromchimpanzees(red).

From: Sundararamanetal.(2013) Plasmodiumfalciparum-likeparasitesinfectingwildapesinsouthernCameroondonotrepresentarecurrentsourceofhuman malaria.ProceedingsoftheNationalAcademyofSciencesUSA,110,7020–5.

basal)thantheanimal-adapted Mycobacteriumbovis (Arnold2007, BritesandGagneeux2015, Brosch etal.2002).Thisevolutionarystoryappearsmore complexthatthoseofmalariaandHIV/AIDS!

1.5 Barrierstoemergence

Manypathogenswithzoonoticoriginthatbecame adaptedtohumanpopulationsaretermed‘crowd diseases’,becausethepathogenscouldonlybecome establishedinhumansocietiesthathadreached highenoughdensitiestoallowsustainedtransmissionandreplacementofsusceptibleindividuals.Crowddiseasestendtobeveryinfectiousand causesomeantibody-derivedresistance.Historically,someofthesepathogenspilloversoccurred synchronouslywiththedevelopmentofagriculture anddomestication,implyingapathogenspillover doublejeopardy:increasedexposuretolivestock species,andincreasedhumandensities(Wolfeetal. 2007, Woolhouseetal.2013).

However,notallanimalpathogensspilloverand becomehuman-specializedpathogens(Wolfeetal. 2007),eveniftherearemanyhumanslivingin oneplace.Humansmightnotbesusceptibleto thepathogen,oropportunitiesforhumanexposure maybelimited,evenifapathogenispotentially capableofinfectingpeople.Behaviourcanreduce orpreventexposures.Forexample,insteadofusing yourteeth,usingalternativecastrationtechniques toreducetheriskof Campylobacterjejuni transmissionfromlambs;oravoidingpotentialexposure toprionslikebovinespongiformencephalopathy (BSE),alsoknownasmadcowdiseaseorchronic wastingdisease,bynoteatingpartsoftheanimal’s centralnervoussystem(CNS)andlymphoidtissue.

1.6 Ebolavirusasacasestudy ofspillover

Guinea,Liberia,SierraLeone,Spain,UnitedStates,etc., 2013–2016—Firstdescribedin1976fromanoutbreakintheremotevillageofYambuku,Democratic RepublicoftheCongo,andnamedaftertheEbola River,theEbolavirus(orZaireebolavirus)isa zoonoticpathogenthatcancausehighmortality amonghumancases(i.e.ahighcase-fatalityrisk or,morecommonlyknownas,casefatalityrate).

SpillovereventsforEbolavirusinhumanpopulationshavebeenlinkedtoexposurefromdiverse animalsources,e.g.carcassesofduiker(asmall forestantelope),gorillas,andchimpanzees(Rouquetetal.2005).Typically,Ebolavirusoutbreaks haveoccurredinremotelocationsinCentralAfrica: Gabon,theRepublicofCongo,andtheDemocratic RepublicofCongo.Betweendescriptionin1976 andearly2014,thelargestknownEbolavirusdiseaseoutbreaksinfectedapproximately300people, and47–89%ofcaseswerefatal.Aftertheoutbreaksended,severalyearsnormallypassedbefore anotherEbolavirusoutbreak.Thisboom-and-bust patternisoftenexhibitedbyzoonoticdiseases. Illnessstrikesmenwhentheyareexposedtochange. —Herodotus

Morerecently,though,outbreakshavefollowed verydifferenttrajectories(Fig. 1.7).InDecember 2013,an8-month-oldboyfromasmallvillagein south-easternGuineawasbelievedtobetheindex caseforanEbolavirusepidemic(Baizeetal.2014, MaríSaézetal.2015).Thoughthecauseoftheboy’s deathwentunrecognizedatthetime,theEbola viruscausedfurthercasesof‘fataldiarrhoea’and anofficialmedicalalertwasissuedtodistricthealth officialsinlateJanuary2014.Thevirusspreadto Conakry,Guinea’scapitalcity,andwasconfirmed asZaireebolavirusinMarch2014.Guineaisabout 2500kmfromthetraditionalrangeofEbolavirus inCentralAfrica.Inthiscase,althoughithasbeen recognizedinCentralAfricaforfourdecades,Ebola virusalsoconstitutesan emerginginfectiousdisease,becauseitisa pathogenthathasrecently increasedinincidenceorgeographicrange,even ifithasinfectedhumanshistorically(Jonesetal. 2008).

Ebolavirushadneverinfectedpeopleanywhere closetoWestAfricabefore,andtheregionwas blindsided.Ontopofthat,thiswasthefirsttime thatEbolaviruswasactiveinheavilypopulatedand connectedurbancentresratherthanisolated,rural areas.Acombinationofdensepopulations,inadequatepublichealthinfrastructureandresponse,and alackofpriorexperiencewiththedisease,meant thattheEbolavirusspreadamonganunprecedentednumberofpeople.ByJuly2014,thevirus wasalsopresentinMonroviaandFreetown,the

Figure1.7 EbolavirusoutbreaksinAfricafrom1976to2020,scaledbytheoutbreaksize(numberofcases;blue = deaths,yellow = survived).RecentoutbreaksinWestAfricaandtheDemocratic RepublicofCongohavebeenmuchlargerthanpreviousoutbreaksandaffectedmoreurbanizedpopulations.

CreatedbyHannaD.Kiryluk.

capitalsofGuinea’sneighbouringcountriesLiberia andSierraLeone.InfectedtravellersormedicalpersonnelwerereportedinItaly,Mali,Nigeria,Senegal,Spain,andtheUnitedStates.Theofficialtallies forthepandemicinGuinea,Liberia,andSierra Leonewere28,610reportedcases,with11,308fatal cases.

DuringtheWestAfricanEbolavirusoutbreak, speculationwasrifethattheviruswouldevolve tobecomemoredeadlyandtransmissible. Newly evolvingstrainsofpathogen areanotherclassof emerginginfectiousdisease (Jonesetal.2008).Normallycirculatinginwildlifespecies,Ebolavirus certainlymutatedduringtransmissioninthisnaive humanpopulation(e.g. Gireetal.2014).However, themutationsthataccrueddonotseemtohave affecteddiseaseprogression,atleastin invivo laboratoryanimalmodels(miceandmacaques)(Marzi etal.2018).Instead,thespreadofEbolavirusinthe WestAfricaepidemiccanbebetterexplainedbythe socialcontextofcloselyconnectedhumanpopulations,andnotastheresultofchangesinthevirus’s intrinsicbiologicalproperties(Marzietal.2018).

1.7 Improveddiagnosticsandincreasing rateofpathogendiscovery

Manyemerginginfectiousdiseasesareprobably instancesofrecentscientificdescription,rather thannovelintroductionstohumanpopulations (Gireetal.2012).Illnessesoftendisplay‘flu-like symptoms’suchasfever,headache,andnausea. Withoutproperlaboratorydiagnostics,itisdifficult todiscernwhetherthesesymptomsarearesult ofmalaria,typhoid,shigella,orevenmildcasesof viralhaemorrhagicfever.Thus,‘rare’spilloversof zoonosesintohumanpopulationsareperhapsmore frequentthanrecognized,andonlyconsideredrare becausesurveillanceanddiagnosticsarelackingor notapplied.

Diagnostictestsandourabilitytodescribe pathogensareconstantlyimproving.Considerthat whenplagueemergedacrosstheglobearound theturnofthe20thcentury—newlyinvadingthe UnitedStates,Australia,Brazil,SouthAfrica— bacteriologywasinitsinfancy,germtheory (therecognitionthatdiseasemightbecausedby microorganismsratherthanbadair)wasanideanot

evenhalfacenturyold,and,intheabsenceofantibiotics,investigativepublichealthagentsmightbeas afearedofinfectedcutsasthethreatofflea-borne bubonicplague(Chase2004).Now,moleculartechniquescandiscernpreviouslyunknownpathogens withindaysandevenhoursoftheobservationof suspiciousnewillnessesusinggenomictechnologies,e.g.thediscoveryofthecoronavirusesthat causedMiddleEastrespiratorysyndrome(MERS) in2012(Zakietal.2012)andtherelatedSARS-CoV-2 inChinain2020(Zhouetal.2020).

Itisoftensuggestedthattherateofemergence ofinfectiouszoonoticdiseaseishigherintheearly 21stcenturythanithasbeeninthemoredistant past;aresultofcombineddriversofemergencesuch ashumanpopulationgrowth,populationdensity, industrializationandchangingfarmingmethods, globalizationofgoodsandhumantransport,andso on(seeChapters9–11).Thishypothesisisadifficultonetotest(Woolhouseetal.2013)!Arguably, therehavebeenjustahandfulofgloballydevastatingEIDeventsinthepastcentury,e.g.‘Spanish’ H1N1influenza(1918–1920)andotherinfluenza outbreaks;HIV-1enteringhumanpopulationsseveraltimesinthe20thcentury;thecurrentSARSCoV-2pandemic.Otherevents,liketheSARScoronavirusoutbreakin2002–2003(see Chapter8),had substantialimpactsuponeconomies,government policies,andpublicperception,butitsimpactspale incomparisontoHIV,H1N1influenza,orSARSCoV-2.Simultaneously,otherdevastatingzoonoses likeplague,whichdevastatedmedievalEurope, representlessofacurrentthreatbecauseofantibiotics,sanitation,andurbanization.Havebetterpublichealthresponsespreventedincreasedmortalitiesfromemergingpathogens?Undoubtedly.The impression,then,ofamodernworldundergoing unprecedentedthreatsofzoonoticepidemicsisless clearcutwhenexaminedinalongerhistorical context.

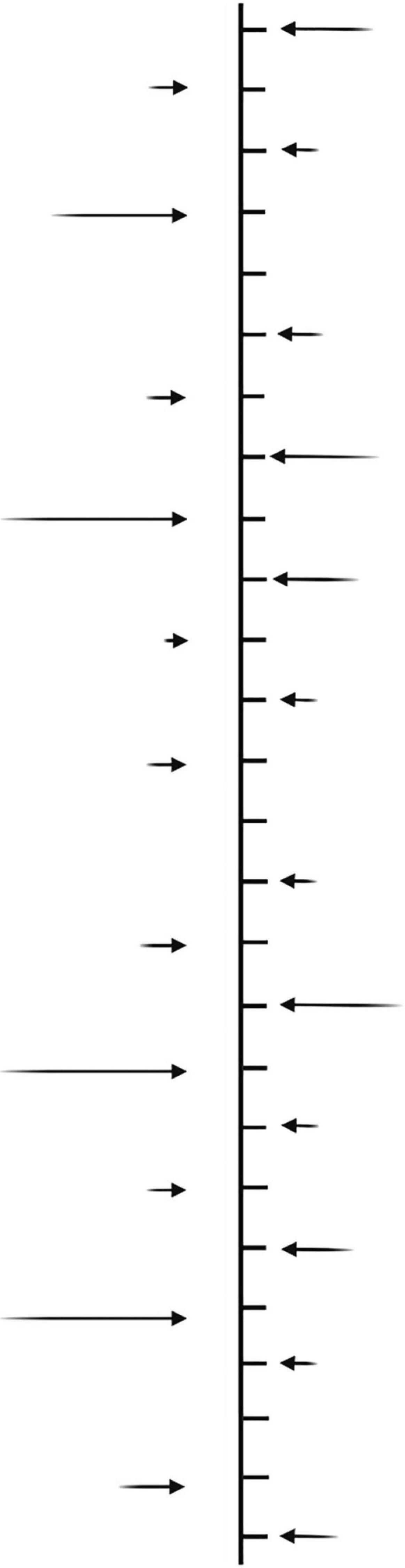

Perhapslessdebatableisthepatternofincreased emergenceofzoonosesinnewpopulationsandnew geographiesasaresultofglobalizationandnew densehumanpopulations(Fig. 1.8).Still,though, advancesindiagnostictechniquesandincreased interestinEIDsmeanthatpatternsofdisease emergenceshouldbeconsideredwithnuanceand thoughtfulness.

Lassa Fever (Nigeria, Togo, UK) Yellow Fever (Kenya) Ebola (DRC) Monkeypox (Europe and North America)

Monkeypox (Nigeria) Yellow Fever (Brazil) Rat hepatitis E virus

Avian Influenza H7N9

Avian Influenza H10N8 Sosuga virus

Chikungunya (Caribbean)

Variegated Squirrel Bornavirus 1

SARS-CoV-2

Zika (Americas)

Lassa Fever (Ghana) Swine Influenza A H3N2v

SARS-CoV EBLV-2 (Scotland) Avian influenza A H5N1 Melaka (Malaysia) Lujo virus (Southern Africa)

Avian Influenza A H5N1 (Hong Kong) West Nile virus (USA) Itaya virus (Peru)

Yellow Fever (West/Central, Africa) Ebola (DRC)

199719981999 2000 200120022003 200420052006200720082009 2010 2011 2012

MERS-CoV Mojiang Paramyxovirus Ebola (West Africa) Avian Influenza H5N6 Lassa Fever (Benin) Bourbon virus CCHF (Spain) Chikungunya (Pakistan) Lassa Fever (Togo) Ntwetwe virus Avian Influenza H7N4 Monkeypox (Liberia, UK) Nipah virus (India)

Pandemic Influenza A H1N1 Heartland virus Bas-Congo virus Lassa Fever (Mali) Huaiyangshan virusSFTS virus

Human CoV HKU-1 Human retroviruses HTLV3 HTLV4 Zika (Micronesia)

Nipah virus (Malaysia) Ngari virus (East Africa) Rift Valley Fever (Saudi Arabia & Yemen) Monkeypox (USA) Avian Influenza H7N7 (Netherlands) Chapare virus (Bolivia)

Figure1.8 Atimeline(1997topresent)ofzoonoticemergenceandspilloverofsomeRNAvirusesandmonkeypoxvirus.Repeatspilloversareindicatedinred;thecountriesinvolvedarein parentheses.Threerecentemergingcoronaviruspathogensarelabelledwithlargefont(i.e.SARS-CoV,MERS-CoV,andSARS-CoV-2).Abbreviationsinclude:EBLV-2,Europeanbatlyssavirustype2; DRC,DemocraticRepublicofCongo;HKU-1,HKU-1coronavirus;HTLV3,humanT-lymphotropicvirustype3;HTLV4,humanT-lymphotropicvirustype4;SFTS,severefeverwiththrombocytopenia syndromevirus;CCHF,Crimean-Congohaemorrhagicfevervirus.

From Keuschetal.(2022)

1.8 Epidemiologymeetsdiseaseecology

Wheninfectinghumans,emerginginfectiousdiseasesaremainlytheconcernof epidemiologists whostudy thedistributionanddeterminants ofhealth-relatedstatesoreventsinspecified (human)populations,andtheapplicationofthis studytocontrolhealthproblems.Traditionally, epidemiologistshavenotoftenbeenexpertsin theanimalcomponentofcross-speciespathogen transmission.

Instead,studyofdiseasetransmissioninanimalpopulationshasbeenthepurviewof disease ecologists Broadly, ecology isthestudyofthe distributionoforganismsandtheirinteractions witheachotherandtheirenvironment,anddiseaseecologypaysspecialattentiontotheecology ofinfectiouspathogens.Inessence, diseaseecology isthe multidisciplinarystudyoftheinteractionsandcausalrelationshipsbetweenhosts, pathogens,andvectorswithinthecontextoftheir environmentandevolution,embracingmoleculartopopulationscales,andoptimisticallyprovidinginsightsintoforecastingdiseaseriskand transmission (Stapp2007, Waller2008, Kilpatrick andAltizer2010, KoprivnikarandJohnson2016) (Box 1.1).Diseaseecologyoftenbroachesexpertise fromfieldsasdiverseasparasitology,mathematics,engineering,conservation,climatescience,and publichealthpolicy.

Inthisbook,wemostlyfocusontheepidemiologyandecologyofzoonoticinfectiousdiseases andwildlifepathogens,butwealsoillustratemechanismsandphenomenausingexamplesofinfectiousdiseasesinpopulationsofdomesticanimals. Admittedly,thereisabiastowardssystemsthat wearefamiliarwithorexcitedby,e.g.plague, histoplasmosis,theSerengeti,tick-bornediseases, mange,Ebolavirus,andnorthernhairymammals.Wealsosufferbiasesbasedonourbackgrounds:weareallwhiteacademicswithrootsin thenorthernhemisphere.Wehavetriedtoinclude casesoutsideofourexpertise,butwewillhave missedthingsandwewillhavemademistakes. Wewillwelcomefeedbacktobroadenthescope ofthebook’stopicsforthesecondandthird editions.

1.9 Whystudytheecologyand epidemiologyofinfectiousdisease?

Wewouldarguethatnostrilticks,lambcastrations, sickcowboys,andfatalhaemorrhagicviruses spreadingfromunknownsourcesacrosstheworld shouldbeanswersenough!Whywouldyoustudy anythingelse?

However,thereareotherreasonsthatthisfield, andhopefullythisbook,shouldexciteyourinterest.DavidQuammen,theauthorof Spillover (which willbemuchquotedinthisbook),suggeststhat zoonosis is‘awordofthefuture,destinedforheavy useinthetwenty-firstcentury’(Quammen,2012). Zoonoticdiseasesand/ortheirvectorsarecertainly emergingandshiftingingeographicalscopeand incidence(Jonesetal.2008).Changesindistribution maybeduetohabitatchange,climatechange,globalization,shiftsinhostcommunityecology,happenstance,oracombinationofthesefactors(e.g. Chapters9,10and11).Itisanexcitingtimetobe monitoringandattemptingtoexplainthefluctuatingpatterns.Forthemoremercenaryamongus,the fieldofdiseaseecologyalsooffersjobopportunities.Understandingprocessesinfluencingzoonoses anddiseaseincidenceinhumanpopulationsisan importantareaofstudy,asistheabilitytoinnovate andimplementinterventionsthatcancombatand controlthediseases.

Theappliednatureofthephenomenacanalso berewarding.Devotingtimeandefforttounderstanding,forexample,interactionsbetweenaharmlessandobscureparasiteincharismatic-but-obscure lizardsmaybeinherentlyinterestingtosome (SalkeldandSchwarzkopf2005),butothersmay revelintheirworkhavingsomerelevancetoconservationscience,orpublichealthimpacts,orenvironmentalpolicy.Indeed,thisaddededgeofpotential implicationsoftheresearchcanaddheatandpassiontodebatedhypotheseswithindiseaseecology, whichlendsthetopicmotivationandinterest,even tothoseoutsidethefield.

Likeallgoodscience,diseaseecology should be hypothesisdriven.Becausenewpathogensare emerging,thereisthethrillofdevelopinghypothesesatthemostfundamentallevel:whatmightthe causeofthisnewdiseasebe?Wherediditcome