PatternsofEastAsianHistory

CHARLESA.DESNOYERS

La Salle University

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford.ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch, scholarship,andeducationbypublishingworldwide.OxfordisaregisteredtrademarkofOxfordUniversityPressintheUKand certainothercountries.

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress 198MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY10016,UnitedStatesofAmerica.

©2020byOxfordUniversityPress

FortitlescoveredbySection112oftheUSHigherEducationOpportunityAct,pleasevisitwww.oup.com/us/heforthelatest informationaboutpricingandalternateformats.

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedinaretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyany means,withoutthepriorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermittedbylaw,bylicense,orunder termsagreedwiththeappropriatereproductionrightsorganization.Inquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,attheaddressabove.

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer.

LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationData

Names:Desnoyers,Charles,1952-author.

Title:PatternsofEastAsianhistory/CharlesA.Desnoyers.

Description:Firstedition.|OxfordUniversityPress:NewYork,[2019]|Includesbibliographicalreferencesandindex.

Identifiers:LCCN2018044956|ISBN9780199946464(pbk.)|ISBN9780199946488(ebook)

Subjects:LCSH:EastAsia—History.

Classification:LCCDS511.D472019|DDC950—dc23LCrecordavailableathttps://lccn.loc.gov/2018044956

987654321

PrintedbyLSCCommunications,UnitedStatesofAmerica

BRIEFCONTENTS

LISTOF MAPS

PREFACE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTESON DATESAND SPELLING

ABOUTTHE AUTHOR

PARTI CREATINGEASTASIA

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

TheRegionandPeople

TheMiddleKingdom:Chinato1280

InteractionandAdaptationontheSiniticRim:Korea, Japan,andVietnamtotheMongolEra

TheMongolSuper-Empire

PARTII RECASTINGEASTASIATOTHEPRESENT

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

FromSuper-PowertoSemi-Colony:ChinafromtheMing to1895

Becoming“TheHermitKingdom”:KoreafromtheMongol Invasionsto1895

From“LesserDragon”to“Indochina”:Vietnamto1885

BecomingImperial:Japanto1895

FromReformtoRevolution:Chinafrom1895tothe Present,PartI

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Epilogue

FromContinuousRevolutiontoAuthoritarianModernity: Chinafrom1895tothePresent,PartII

AHouseDivided:KoreatothePresent

Colonized,Divided,andReunited:VietnamtothePresent

BecomingtheModelofModernity:JapantothePresent BreakneckChangeandtheChallengeofTradition

GLOSSARY

CREDITS

INDEX

CONTENTS

LISTOF MAPS

PREFACE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTESON DATESAND SPELLING

ABOUTTHE AUTHOR

PARTI CREATINGEASTASIA

Chapter 1

TheRegionandPeople

VariedGeographies

The Chinese Landscape

The Great Regulator: The Monsoon

Mountains and Deserts

Eurasia’s Eastern Branch: Korea

The Island Perimeter: Japan

The Southern Branch: Vietnam

EastAsianEthnicitiesandLanguages

China and Taiwan

Tibet

Mongolia

Korea

Japan

Conclusion

Chapter 2

TheMiddleKingdom:Chinato ChinaandtheNeolithicRevolution

Neolithic Origins

TheFoundationsoftheDynasticSystem

The Three Dynasties: The Xia

The Three Dynasties: The Shang

The Three Dynasties: The Zhou

Economy and Society

New Classes: Merchants and Shi

Family and Gender in Ancient China

Religion, Culture, and Intellectual Life

Chinese Writing

Ritual and Religion

TheHundredSchools:ConfucianismandDaoism

Self-Cultivation and Ritual: Confucius

Mencius and the Politics of Human Nature

Paradox and Transcendence: Laozi and Daoism

TheStructuresofEmpire

The First Empire, 221 to 206 BCE

Qin Shi Huangdi

The Imperial Model: The Han Dynasty, 202 BCE to 220 CE

Expanding the Empire

Downturn of the Dynastic Cycle

The Centuries of Fragmentation, 220 to 589 ce

China’s Cosmopolitan Age: The Tang Dynasty, 618 to 907

Buddhism in China

PatternsUp-Close:CreatinganEastAsianBuddhistCulture

The Period of Expansion: Emperor Taizong

“Emperor” Wu

Cosmopolitan Autumn

An Early Modern Period? The Song

The Southern Song Remnant

The Mongol Conquest

Economics,Society,andGenderinEarlyImperialChina

Industry and Commerce

Agricultural Productivity

Gender and Family

Thought,Science,andTechnology

The Legacy of the Han Historians

Neo-Confucianism

Poetry, Painting, and Calligraphy

Technological Leadership

Conclusion

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

InteractionandAdaptationontheSiniticRim:Korea, Japan,andVietnamtotheMongolEra

FromThreeKingdomstoOne:Koreato1231

The “Three Kingdoms”

Korea to the Mongol Invasion

Economy and Society

Religion, Culture, and Intellectual Life

Isolation,Interaction,andAdaptation:Japanto1281

Jomon and Yayoi

Early State Building

Imperial Rule

Economy and Society

Family Structure

Religion, Culture, and Intellectual Life

Buddhism in Japan

PatternsUp-Close:FromPeripherytoCenter:Nichiren,Buddhism,and Japan

Forging a New Japanese Culture

BordersofInfluenceandAgency:Vietnam

Neolithic Cultures

Village Society and Buddhism

The “Far South”

Independence and State Building

Economy and Society

Officials, Peasants, and Merchants

Women and Family

Religion, Culture, and Intellectual Life

Chu Nom

Conclusion

TheMongolSuper-Empire

GenghisKhanandtheMongolConquest

Strategies of the Steppes

Clashing Codes of Combat

Assimilating Military Technologies

The Mongol Conquest: The Initial Phase

The Drive to the West

PatternsUp-Close:PaxMongolica

Subduing China

From Victory to Disunity

Overthrow and Retreat

TheMongolCommercialRevolution

Rebuilding Agriculture and Infrastructure

Role Reversal: Artisans and Merchants

Family,Gender,Religion,andCulture

Egalitarian Patriarchy?

Religion: Toleration and Support

Conclusion

PARTII RECASTINGEASTASIATOTHEPRESENT

Chapter 5

FromSuper-PowertoSemi-Colony:ChinafromtheMing to1895

RemakingtheEmpire:TheMing

Centralizing Government and Projecting Power

Toward a Regulated Society: Foreign Relations

The End of the Ming

TheEraofDominance:TheQingto1795

The Banner System

Universal Empire

Pacification and Expansion

Encounters with Europeans

Regulating Maritime Trade

TheStruggleforAgencyin“TheCenturyofHumiliation”

The Horizon of Decline: The White Lotus Rebellion

Interactions with Maritime Powers

The Coming of the Unequal Treaties

TheTaipingandNianEras

The Origins of Taiping Ideology

Defeating the Taipings

The Nian Rebellion, 1853–1868

ReformthroughSelf-Strengthening,1860–1895

PatternsUp-Close:TheCooperativeEraandModernization

Chapter 6

Nineteenth-Century Qing Expansion

The Limits of Self-Strengthening, 1860–1895

The Sino–Japanese War of 1894–1895

SocietyandEconomicsinMingandQingTimes

Rural Elites

Organizing the Countryside

Population and Sustainability

The “High-Level Equilibrium Trap” Debate

TechnologyandIntellectualLife

Philosophy and Literature

Poetry, Travel Accounts, and Newspapers

Conclusion

Becoming“TheHermitKingdom”:KoreafromtheMongol Invasionsto1895

TowardSemi-Seclusion

The Mongol Era and the Founding of the Yi Dynasty

The Japanese Invasion

Recovery and the Drive for Stability

The Shadow of the Qing Strangers at the Gates

The Hermit Kingdom

Korea and the Sino-Japanese War

Economy,Society,andFamily

Land Reform

Social Organization

The New Economy

Family and Gender Roles

CultureandIntellectualLife

PatternsUp-Close:TheDevelopmentof Han’Gul

Neo-Confucianism and Pragmatic Studies

Conclusion

Chapter 7

From“LesserDragon”to“Indochina”:Vietnamto1885

TheLesserDragon

Southward Expansion

Perils of Growth

Chapter 8 Rebellion and Consolidation

PatternsUp-Close:TheFrenchasAlliesoftheImperialCourt

CreatingIndochina

First Footholds

Colonization by Protectorate

The Sino-French War

ConflictandCompromise:EconomyandSociety

The New Commercial Development

Neo-Confucianism in Imperial Vietnam

Toward“Modernity”?Culture,Science,andIntellectualLife

Asserting Incipient Nationalism

Struggles of Modernization

Conclusion

BecomingImperial:Japanto1895

TheEraoftheShoguns,1192–1867

Kamakura and Ashikaga Shogunates, and Mongol Attacks

Dissolution and Reunification

TheTokugawa Bakufu

“Tent Government”

Freezing Society

Securing the Place of the Samurai

Tokugawa Seclusion

ReunifyingRule

The Coming of the “Black Ships”

Restoring the Emperor

From Feudalism to Nationalism

The Meiji Constitution and Political Life

Becoming an Imperial Power

Economy,Society,andFamily

Agriculture, Population, and Commerce

Late Tokugawa and Early Meiji Society and Economics

PatternsUp-Close:Japan’sTransformationthroughEastAsianEyes

Railroads and Telegraphs

Family Structure

“Civilization and Enlightenment”

Chapter 9

Religion,Culture,andIntellectualLife

Zen, Tea, and Aesthetics

The Arts and Literature

Bunraku, Noh, Kabuki, and Ukiyo-e

Intellectual Developments

Science, Culture, and the Arts in the Meiji Period

Conclusion

FromReformtoRevolution:Chinafrom1895tothe Present,PartI

TheRepublicanRevolution

The Last Stand of the Old Order: The Boxer Rebellion and War

The Twilight of Reform

Sun Yat-sen and the Ideology of Revolution

The New Warring States Era (1916–1926)

Creating Nationalism

The First United Front

CivilWar,WorldWar,andPeople’sRepublic

The Nationalist Interval

The Long March and Xi’an Incident

East Asia at War

From Coalition Government to the Gate of Heavenly Peace

ANewSocietyandCulture

The New Culture Movement

City and Country

Conclusion

Chapter 10

FromContinuousRevolutiontoAuthoritarianModernity: Chinafrom1895tothePresent,PartII

TheMaoistYears,1949to1976

Early Mass Mobilization Campaigns

Land Reform

The Great Leap Forward

The Hundred Flowers and Anti-Rightist Campaigns

Taking a Breath in the Revolution

Becoming Proletarian: The Cultural Revolution

The End of the Maoist Era

AU-TurnontheSocialistRoad

China’s Four Modernizations

Chapter 11

Modernizing National Defense

The “Fifth Modernization”

TiananmenSquareandtheNewAuthoritarianism

Ending the Colonial Era

Tiananmen Square

“Confucian Capitalism”

Growth and Its Discontents

Tibet and Minorities

Toward Harmony and Stability?

The Olympic Moment

Xi Jinping and “The Four Comprehensives”

PatternsUp-Close:ConfuciusInstitutesandChina’sSoftPower

Society,Science,andCulture

Recasting Urban Life

Modernization and Society

The New Technology

Art and Literature

The Media

Conclusion

AHouseDivided:KoreatothePresent

TheEbbandFlowofColonialism

Military Rule

Relative Restraint: The Cultural Policy

Militarism, Colonialism, and War

PatternsUp-Close:Nationalism,Empire,andAthletics

ColdWar,HotWar,andColdWar

A Korean Civil War?

From Seesaw to Stalemate

PoliticalandEconomicDevelopmentsSouthandNorth Republics and Coups

Land Reform and the Export Economy

From Authoritarian Rule to Democracy

The Democratic Era, 1993 to the Present

TheNewHermitKingdomoftheNorth War by Other Means

Chapter 12

Juche and the Cult of Personality

The Kim Dynasty

Conclusion

Colonized,Divided,andReunited:VietnamtothePresent

TheFirstColonialEra,1885–1945

“The Civilizing Mission” and Rebellion

Reform and Republicanism

Ho Chi Minh and Revolution

PatternsUp-Close:ParsingtheLanguageofIndependence

The War for Independence

TheAmericanWar

Tearing Two Nations Apart

“Peace with Honor” and National Unification

FromReunificationtoRegionalPower

Building the New Socialist State

Politics and Genocide: Fighting the Khmer Rouge

Recovery and Prosperity

Conclusion

Chapter 13

BecomingtheModelofModernity:JapantothePresent

“AWonderfullyCleverandProgressivePeople”

The Russo-Japanese War

The Limits of Power Politics

The Great War and the Five Requests

Intervention and Versailles

Taisho Democracy

MilitarismandCo-Prosperity:TheWarYears

Creating Manchukuo

State Shinto and Militarism

The “China Incident”

World War II in the Pacific

Allied Counterattack

Co-Prosperity and Conditional Independence

Endgame

TheModelofModernity:FromOccupationtothePresent

The New Order: Reform and Constitution

The Reverse Course: Japan and the Cold War

Moving Toward the Twenty-First Century

PatternsUp-Close:Japan’sHistoryProblem

Economy,Society,andCulture

From “Made in Japan” to Total Quality Management

The Dominance of the Middle Class

Women and Family: “A Half-Step Behind”?

Godzilla and Sailor Moon: Postwar Culture

Conclusion

Epilogue

BreakneckChangeandtheChallengeofTradition

OneRegion,ThreeSystems?

Colonialism and Imperialism

Twentieth-Century Conflict and Political Configuration

The“ChineseDream”astheEastAsianDream?

GLOSSARY

CREDITS

INDEX

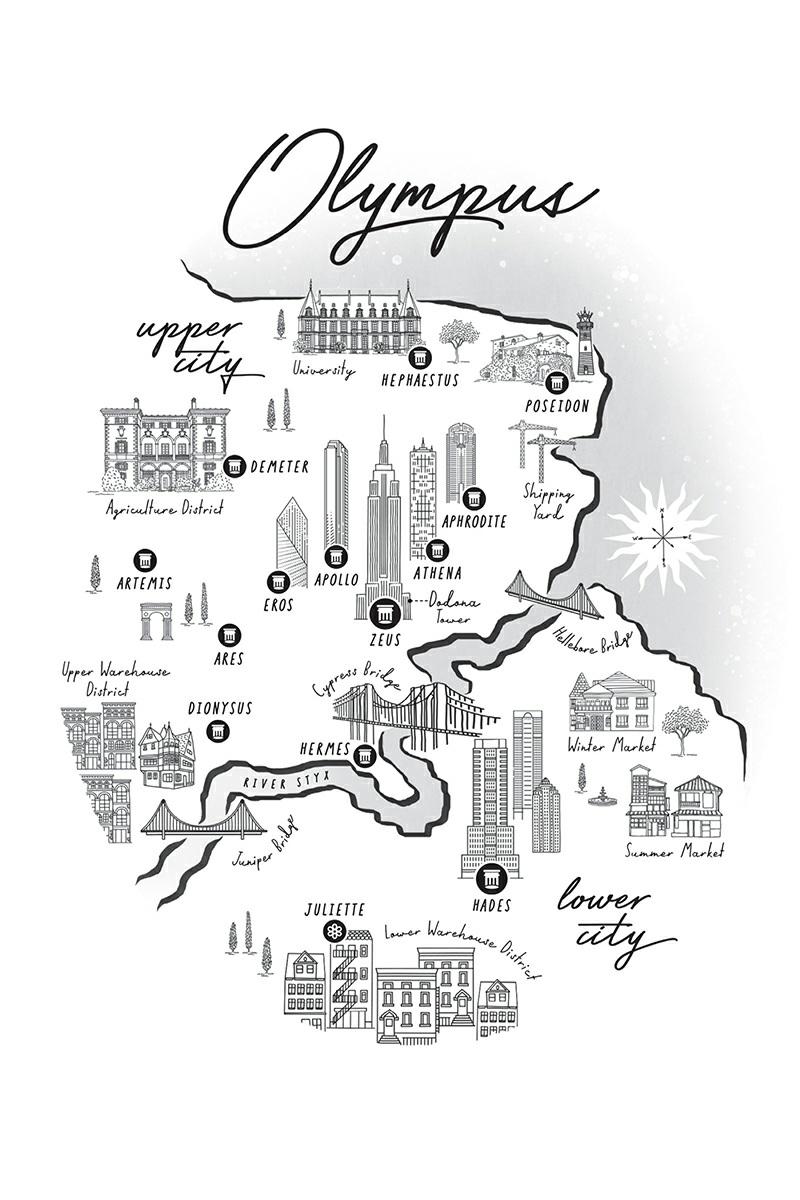

LISTOFMAPS

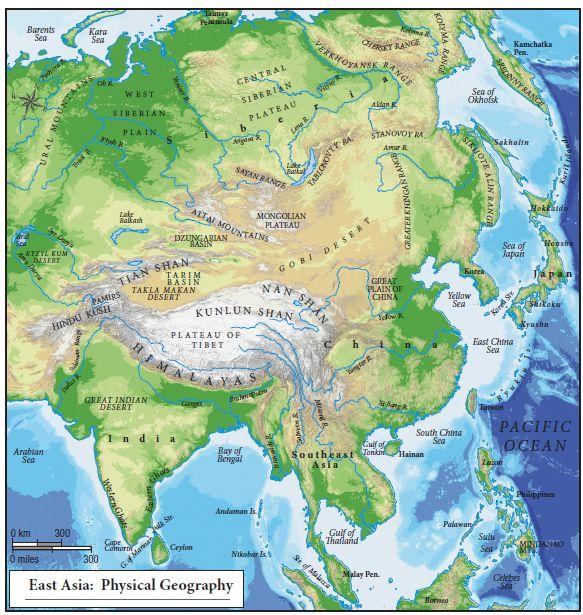

InsideFrontCoverMap.EastAsia:PhysicalGeography

Map1.1.

Map1.2.

Map1.3.

Map1.4.

Map2.1.

Map2.2.

Map2.3.

Map2.4.

Map2.5.

Map2.6.

Map2.7.

Map2.8.

Map3.1.

Map3.2.

Map3.3.

Map3.4.

Map3.5.

Map4.1.

Map4.2.

Map5.1.

Map5.2.

Map5.3.

Map5.4.

Map5.5.

Map5.6.

Map5.7.

Map6.1.

Map6.2.

Map6.3.

China,Mongolia,andTibet:PhysicalGeography

KoreaandJapan:GeographyandClimate

SoutheastAsia:ThePhysicalSetting

MajorLanguageandEthnicGroupsofEastAsia

TheSpreadofFarminginEastAsia

NeolithicChina

TheShangandZhouDynasties

LateWarringStatesandQinUnification

TheHanEmpire

Chinain500 CE

EastandCentralAsiaduringtheTang

TheSpreadofBuddhismto600 CE

Korea,ca.500 CE

KoreaundertheKoryo,936–1392 CE

HeianJapan

MainlandSoutheastAsia,150 BCE–500 CE

DaiViet,ca.1100 CE

TheMongolEmpire

TheMongolHeartland

TheMingEmpireandtheVoyagesofZhengHe

ChinaundertheQing CampaignsofQianlong

TheWhiteLotusMovement,1796–1805

TheTaipingMovement,1850–1864

DunganHuiRebellionandYuqubBeg’sRebellion,1862–1878

TheSino-JapaneseWar,1894–1895

EastandCentralAsia,ca.1200 CE

Hideyoshi’sInvasionsofKorea,1592–1597

ManchuInvasionsofChosonKorea

Map7.1.

Map7.2.

Map7.3.

Map8.1.

Map8.2.

Map8.3.

Map8.4.

Map8.5. Map9.1. Map9.2.

Map9.3. Map9.4. Map9.5.

Map10.1.

Map10.2.

Map10.3.

Map11.1.

Map11.2.

Map11.3.

Map12.1.

Map12.2.

Map12.3.

Map12.4.

Map13.1.

Map13.2.

Map13.3.

Map13.4.

Map13.5.

Map14.1.

MainlandSoutheastAsia,ca.1428

DaiNamandSurroundingRegions,ca.1820

FrenchIndochina

FeudalJapan

MajorDomainsandRegionsintheTokugawaPeriod

ThePacificintheNineteenthCentury

TheSino-JapaneseWar

IndustrializingJapan,ca.1870–1906

TreatyPortsandForeignSpheresofInfluenceinChina,1842–1907

WarlordTerritoriesandtheNorthernExpedition,1926–1928

TheJiangxiSovietandtheLongMarch,1934–1935

JapaninChina,1931–1945

TheChineseCivilWar,1946–1949

ThePeople’sRepublicofChinaandtheRepublicofChina,1950

BorderClashesandTerritorialDisputesbetweenChinaandIndia,1962–1967

OpenCities,SpecialEconomicZones,AutonomousRegions,andSpecial

AdministrativeRegionsinChina,1980–2000319

JapaneseExpansioninNortheastAsia,1870–1910338

KoreaattheEndofWorldWarII348

TheKoreanWar351

FrenchIndochinaandMainlandSoutheastAsia376

VietnamduringtheAmericanWar

ReunifiedVietnam

TheThirdIndochineseWar

TheRusso-JapaneseWar,1904–1905

TheJapaneseEmpirein1920

JapaninChina,1931–1945

WorldWarIIinthePacific

TerritorialClausesoftheTreatyofSanFrancisco,1951

China’sBeltandRoadInitiative

InsideBackCoverMap.ContemporaryEastAsia

PREFACE

Patterns of East Asian History marks the third volume in Oxford University Press’s highly successful Patterns series, which currently includes Patterns of World History in its third edition and Patterns of Modern Chinese History. These offerings are college-level introductory texts whose purpose is to provide beginning students with an entree into complex fields of history with which American students have generally had little or no exposure. The approach of all the volumes revolves around the idea of using recognizable and widely accepted patterns of historical developmentasalooseframeworkaroundwhichtostructurethematerialbothasanorganizational aid to the instructor and as a tool to make complex material more comprehensible to the student. As we have stressed in previous volumes in the series, this approach is not intended to be reductionist or deterministic, or to privilege a particular ideological perspective, but rather to enhance pedagogical flexibility while providing a subtly recursive format that allows abundant opportunities for contrast and comparison among and within the societies under consideration. As with the other volumes in the series, the overall aim is to simplify the immense complexities of historyforthebeginningstudentwithoutmakingthemsimplistic.

All the historical fields covered in these volumes (world history, Chinese history, East Asian history) now face lively internal debates concerning various topics, and one of the goals of the series is to introduce students to these discussions in order to stress the idea that historians are not monolithic in their ideas or approaches, but more often than not disagree with each other, sometimes vigorously. Thus, all the books employ certain pedagogical features designed to enhance the sense that “the past,” as William Faulkner put it so memorably, “is not dead; it isn’t even past.” Chapters begin with a vignette designed to crystallize a particular situation or idea emphasized within that chapter or section and include a feature, “Patterns Up-Close,” designed to examine a particular concept or event at a deeper level to enhance the material in question. Because chapters 9 and 10 constitute essentially one long chapter on China from 1895 to the present, the vignette for both chapters opens Chapter 9 and the Patterns Up-Close feature for both isinChapter10

In the case of East Asia, one problem that immediately presents itself is how to define the area as a specific region. Geography offers some clues but nothing hard and fast and instantly identifiable, such as the Indian subcontinent. China, of course, is at the heart of East Asia geographically, but how far should one define the region beyond its historical borders? Should Mongolia be considered part of East Asia? Should Southeast Asia? In many respects, the cultural connections offer more coherent boundaries, but even these are contested. Some would include what is often called the “Sinitic Frontier” that includes the states and societies on the Chinese periphery that have been touched by Chinese culture in one form or another. This is fairly safe ground for the three states most commonly included in regional histories and sourcebooks: China,

Korea, and Japan. But even these are not always taken together: for example, the Association for Asian Studies organizes its regional councils on the model of “China and Inner Asia,” “Northeast Asia”(includingJapanandKorea),and“SoutheastAsia”(includingVietnam).TheUnitedNations Statistics Division includes Mongolia along with China, Japan, and Korea, although Mongolia shares much less culturally with these three nations than Vietnam, which is listed separately in Southeast Asia. Some regional political spokespeople from countries generally designated as “Southeast Asian” have advocated including the members of their regional Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) along with China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, as comprising a greater“EastAsia.”

One can also find ready opposition to what might be called the “Chinese impact-indigenous response” model. Certainly, much of the history of Vietnam and Korea consists of attempts to break free of Chinese political influence; Mongolians and Manchus have long struggled—even when their empires included China—to not be assimilated culturally by China, and Tibetans and various Central Asian peoples today, as in the past, resist the tide of what they term “cultural genocide”emanatingfromthePeople’sRepublic.

Yet in the case of all these places, contact with China marked vital turning points in their societies. Korean and Vietnamese states for short periods held territory within what ultimately constituted China. More generally, however, both places underwent long periods of invasion and occupation by various Chinese dynasties that left their written language, systems of government, and cultural, philosophical, and religious traditions as their legacies. Japan actively borrowed Chinese systems to make the clan-based central kingdom of Yamato into a self-designated empire. Mongolia existed only as part of a large territorial expanse inhabited by a multitude of nomadic groups who periodically raided and clashed with the Chinese states to the south until the time of Genghis Khan. While remaining culturally distinct from China—even devising their own written language and adopting a variety of religious beliefs—the high point of their imperial ambitions came with the conquest of Song Dynasty China and the creation of their own Chinese regime: the Yuan Dynasty (1280–1368). Tibet, whose language springs from the same family (Sino-Tibetan) as the Chinese dialects, maintained its cultural distinctiveness even when incorporated into the Qing Empire by Manchu rulers—themselves struggling to maintain their own cultural distinctiveness—whosevisionwasauniversalmulticulturalstate.

The often fraught relationship of these states with China raises another conceptual problem in studying the area: the question of modernity. How should we define it, and when can we say it began for the region as a whole? Can we even designate a period for the majority of these states when we might say that their modern periods were under way? In the case of China, scholars have over the years suggested beginning the modern era as late as 1840 and as early as the Song Dynasty (960–1279). For Japan, key dates include the wholesale adoption of Chinese political and cultural systems during the Taika (Great Reform) of 645; the beginnings of imperial Heian Japan (after 794); the creation of the shogunate (1185); the Tokugawa period (1603–1867); the “opening”ofJapanbyPerryin1853;andtheMeijiRestoration(1868–1912).InthecaseofKorea, the coming of Buddhism and Chinese culture (fourth and fifth centuries); the creation of the han’gul writing system (fifteenth century); and the first treaty with Meiji Japan (1876) might all plausibly be used. Similar problems surface with Vietnam. The creation of the Mongol superempire in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries seems a fairly logical and convenient place to situate thestartofthatcountry’smodernperiod.

The Mongol interval, although brief, does provide a kind of jumping off point for the organization of this volume. Recent scholarship has suggested that in controlling such a vast area, encouraging trade, setting up a number of proto-capitalist institutions such as the widespread use of checks, paper money, even insurance, and practicing a considerable degree of religious toleration, the Mongols played a direct role in ushering in the early modern period throughout Eurasia. Moreover, their rule touched every region with which we are concerned, except for Japan—though they made two attempts to invade the island empire. Thus, this volume, like Patterns of Modern Chinese History,beginswithchaptersthatprovideaprologuetowhatwehave designated as the modern period, whereas the greater part of the book covers material after the MongolEmpireacquiredChinain1280.

As noted above, the central approach to this book, as with the others in the series, is that of patterns. Within this overall rubric, a considerable amount of attention is given to three elements: origins, interactions, and adaptations. For example, one noticeable pattern, given the widespread effects of the monsoon, is the dominance of rice production throughout much of the area. This is not to adopt a Marxian “Asiatic mode of production” approach or to point to Karl A. Wittfogel’s insistenceonthedeterminismof“hydraulicsociety,”buttonotethatthetechniquesofwetanddry rice production were widely diffused, widely practiced, and allowed for and demanded substantial populations for production. The exact origins of wet rice cultivation are unknown, but interactions among innumerable persons and groups over the centuries spread and continually revitalized its techniquesandplantstrains,withlocalandregionaladaptationsoverthecourseofmillennia.

More directly traceable are the patterns of cultural diffusion and incorporation—involving origins, interactions, and adaptations from core to periphery—that have continually played out across the region. China’s Shang Dynasty, for example, diffused its culture widely across the YellowRiverbasin.WhentheformerShangclientstateofZhouconqueredtheShang,theyspread much of the Shang culture they had adopted over most of North China. We have noted above the profound cultural exchanges that marked China’s relations with Vietnam and Korea, and from Korea to Japan. Sometimes the periphery becomes the new core: Japan, transformed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries into an aggressively expansive industrial power through contact with the West, became for a time a model for Chinese and other East Asian reformers to emulate. Indeed, it provided an important model for China’s present economic power. Moreover, Japan’scolonialoccupationofKorea,Manchuria,andTaiwanforhalfacenturyleftaconsiderable culturalandindustriallegacyinthoseregions—althoughonesownwithpainandbitterness.Asthe world’s second-largest economy, China has emerged as the dominant Asian core—with Japan and India close behind—and is daily accelerating its cultural and economic influence on the world stage.

A related pattern is one rather like the relationship between ancient Greece and Rome: the latter, it was said, conquered militarily, but the former conquered the conquerors culturally. From the time of the Shang and Zhou down to the present, China’s immense cultural gravity has pulled those outsiders who have militarily subdued it or sought to subdue it into a graduated process of Sinification. Some, like the nomadic groups of the northern tier, sensing opportunity during dynastic upheavals, have conquered regions, settled down, and intermarried with the locals. For example, the Toba of the Northern Wei kingdom ultimately begat the Sui and China’s most cosmopolitan dynasty, the Tang. Although they conquered the world’s largest empire, the Mongol Yuan Dynasty in China found itself forced to adapt in many ways to Chinese norms of

government, and constantly strove to maintain its own culture in the face of immense pressures to assimilate. This was even more pronounced in the case of China’s last imperial dynasty, the Manchu Qing. Having already adapted to Confucian norms before their conquest of China, the Manchus struggled to keep from being ethnically, physically, and culturally subsumed by their subjectsuntilthedynastytoppledin1912.

This book is organized into thirteen chapters plus a brief epilogue, a number that allows instructors to move at a comfortable pace within a standard semester. The chapters are relatively short, enabling instructors at institutions using a trimester or quarter system to utilize the book as well. This volume is laid out in two parts: Part I, “Creating East Asia,” includes Chapters 1 through 4, from Neolithic times through the Mongol interval. Part II, “Recasting East Asia to the Present,” follows the histories of individual countries from the fifteenth century onward. As in the other Patterns volumes, chapters generally follow a format of political history, followed by economic, social, cultural, and scientific/technological issues, as well as the opening vignette and “Patterns Up-Close” feature mentioned above. Thus, courses employing this book can also use it thematicallyintermsoftheinternalstructureofthechaptersandtherecurrentemphasisonvarious historicalpatterns.

CharlesA.Desnoyers,November24,2018

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

As was the case with the other books of the Patterns series—Patterns of World History and Patterns of Modern Chinese History—the conception and creation of this volume have been an exciting and wonderfully collegial enterprise. In all three books, I have had the singular good fortune to have benefited from the guidance, insight, and inspired eyes and hands of the talented and dedicated people at Oxford University Press. Hence, I wish to thank them all collectively for theircontinualenthusiasmandhardworkinbringingthisvolumetopublication.Ofparticularnote is editorial assistant Katie Tunkavige, who took what had been all too many vague directions regarding illustrations and turned them into vibrant and often stunning embodiments of the material described in the text. I would like to thank Claudia Dukeshire, who handled the editorial production,andPattiBrecht,whocopyeditedthetext.

I have also received considerable help and support from a number of valued colleagues. As theywere with Patterns of Chinese History, my HistoryDepartment chair, Stuart Leibiger, andthe members of the Sabbatical Committee at La Salle University deserve great thanks for allowing me the time needed to work on this manuscript. Needless to say, those dear friends and colleagues who taught and traveled with me have my special thanks in making this project possible. To my students in the classroom over the years, you have given me far more than I can say in inspiring thewritingofthisbook.

I would like to offer a special kind of thanks to my friend and editor, Charles Cavaliere. More than anyone, Charles has made these three volumes possible: in conceiving them, keeping us on task in writing them, in providing an endless stream of suggestions with regard to the design, format, and illustrations of the books, and in supervising every phase of their production. He has indeedbeentheprimemoverofthePatternsseries.

No note of thanks would be complete without acknowledging those readers and reviewers whose comments have added so much to this volume: Clayton D. Brown of Utah State University; Desmond Cheung, Portland State University; Margaret B. Denning, Slippery Rock University; David Kenley, Elizabethtown College; Charles V. Reed, Elizabeth City State University; Walter Skyra, University of Alaska Fairbanks; John Stanley, Kutztown University; and Peter Worthing, Texas Christian University. They all have my heartfelt gratitude for their advice and criticism, and I hope I have done them justice in incorporating their suggestions. Any errors of fact or interpretationthatremainarestrictlymyown.

Finally,IwishtothankmywifeJackiforherimmensepatience,fortitude,andsupport—tosay nothing of her faith, hope, and love—throughout all these projects. None of this would have been possiblewithoutyou.

NOTESONDATESANDSPELLING

The dating system used in this book is the current standard for historians, in which Before Common Era (BCE) and Common Era (CE) have supplanted the older and more Western-centered BC and AD. Events in the remote past are sometimes given as “years ago” (YA) or “before present” (BP). The spellings of names, places, objects, etc., that have long remained standard have been retained for the convenience of the reader. In most cases, these will also include current academic romanizations. Thus, the city of Guangzhou will also be referenced as Canton, and Jiang JieshiwillbeidentifiedbythemorewidelyrecognizedspellingofhisnameasChiangKai-shek.

The system used in rendering the sounds of Mandarin Chinese—the northern dialect that has become, in effect, the national spoken language in the People’s Republic of China and in the Republic of China on Taiwan—into English in this book is hanyu pinyin, usually given as simply pinyin. Most syllables are pronounced as they would be in English, with the exception of the letter q, which has an aspirated “ch” sound. Zh carries a hard “j,” while j itself has the familiar soft Englishsound.Somesyllablesarealsopronounced(particularlyintheregionaroundBeijing)with aretroflex“r.”Thus,theword shi insomeinstancessoundsmorelike“shir.”Finally,theletter r in thepinyinsystemhasnodirectEnglishequivalent,butmaybeapproximatedbythecombiningthe soundsof“r”and“j.”

Japanese terms have been romanized according to a modification of the Hepburn system. The letter g is always hard; vowels are handled as they are in Italian—e, for example, carries a sound like“ay.”Diacriticalmarkstoindicatelongvowelsounds,however,havebeenomitted.

For Korean words, this book uses a variation of the McCune–Reischauer system, which remains the standard used in English-language academic writing, again eliminating diacritical marks.Hereagain,thevowelsoundsarepronouncedmoreorlesslikethoseinItalian.

For Vietnamese, the standard renditions are based on the modern Quoc Ngu (“national language”) system in current use in Vietnam. The system was developed in part by Jesuit missionaries and based on the Portuguese alphabet. As in the other romanizations of East Asian languages,thediacriticalmarkshavebeenomitted.

Because of the several competing systems of romanizing Mongolian terms, such as Mongolian Cyrillic (BGN/PCGN), the closest Latin equivalents have been used in this book. Famous names, such as Genghis Khan (more properly transliterated as “Chinggis), have been given according to standard,widelyrecognizedspellings.