Introduction

Becauseouratmospherecontainsoxygenandwatervapour,becauseaqueousfluids areomnipresentattheEarth’ssurfaceasgroundwaters(springs,wells)orasrun-off waters(rivers,lakesoroceans),oxides,amongwhichmagnetite,quartz,orthevarious typesofsilicates(feldsparsorpyroxene)formthemajorcomponentsoftheEarth’s crust.Oxidesarealsocontainedinthesoilandstronglyinteractwiththebiosphere. Thus,itisfairtosay:oxidesareeverywherearoundus.

Thediversityofoxidestructuresandcompositionsisastonishing,especiallyin comparisonwithmetalsorelementalsemiconductors.Evensimplebinaryoxideswith asingletypeofcationsdisplaybulkstructureswhichrangefromthesimplesttomore complexones:rock-salt,wurtzite,spinel,corundum,fluorite,orantifluorite.Moreover, manyoxidesmayexistunderseveralpolymorphicformsdependingonthermodynamic conditions.Assoonasseveralcationsarepresent,asinperovskitesoraluminosilicates (claysorzeolites),thestructuralcomplexityincreases,concomitantwithmultiplepossibilitiesofcationsubstitutionsandmultipletypesofstructuraldefects.Physicists havelongconsideredoxidesasuninteresting,classicalobjectswithpropertiesonly drivenbysimpleelectrostaticforces.However,theirelectroniccharacteristicsareas variedastheirstructures.Apartfromthewell-knownlarge-gapinsulators,someoxidesaresemi-conducting,othersaremetallicorevensuperconducting,andallflavours ofmagnetismmaybeencountered.Thiscomplexityrepresentsachallengefortheir controlledsynthesisandtoapreciseengineeringoftheircharacteristics,butitalso offersatremendousrichnessofapplications.

Theinterestofthefieldliesinitsinterdisciplinarynatureandinthediversity ofquestionsitraises,bothonafundamentalandonanappliedlevel.Itgathersresearchersfromvarioushorizons:geophysicistsandgeologistsasfarastheformation andweatheringoftheEarth’srocksareconcerned;mineralogistsinterestedinthe structureandcompositionofcomplexminerals;toxicologistswhodeciphertheinteractionsbetweensmalloxideparticlesandthebiologicalmedium;andchemistsbecause oxidesaregoodcatalysts,largelyused,forexample,inpetrochemistry.Oxidesarealso oftenpresent,althoughinanuncontrolledway,wheneveranobjectisincontactwith theambientatmosphere.Theyplayafundamentalroleincorrosionprocessesandin thesurfacepropertiesofrealmaterials.Finally,theyofferalargefieldofinvestigations tosurfacescientists.

Thelastthreedecadeshavewitnessedimportantadvancesinthecontroloftheir synthesis,sothatreproducibleandwell-characterizedsamplesmaynowbeobtained.

OxideThinFilmsandNanostructures.FalkoP.NetzerandClaudineNoguera,OxfordUniversity Press(2021). c FalkoP.NetzerandClaudineNoguera.DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198834618.003.0001

Thepresentsituationbearsnoresemblancewiththatwhichprevailedatthestartof theso-called‘high-Tc’era,which,quiteunexpectedly,revealedthatsuperconductivity existsinsomecopperoxidecompoundswithtransitiontemperaturesabovethatof liquidnitrogen.Because,atthattime,theimportanceoftheoxygenstoichiometry hadnotbeenperceived,forseveralyearsmostexperimentalresultsturnedouttobe unreliable.Today,thisisnolongerthecase.Playingwiththermodynamicconditions and,inparticular,theoxygenpartialpressure(butalsothewaterpartialpressure) duringsynthesisisalevertoobtainoxidesamplesofprecisepredefinedstoichiometry, aparticularcrucialrequirementforstudiesatthenanoscale.Inparallel,sophisticated meansofcharacterizationhavebeendeveloped,inparticulardiffraction,microscopy, andspectroscopymethodsavailableinsynchrotronfacilities,butalsocalorimetric methodsforthestudyofnanoparticlephasediagrams,orvarioustypesofscanning microscopy/spectroscopymethods.Thankstotheever-increasingcomputingpower relevantsimulationsmaynowbeperformed,withabetteraccountofstrongelectron correlationeffects,oflargenumbersofatoms,orofprocessesonlongtimescales.

Forallthesereasons,oxidesarenolongerthe‘dirty’materialsofthepast,but haveintegratedthetechnosphereasactiveandpassivecomponentsinourtechnologicalsurroundings.Understandingthestructureandpropertiesofoxidesisthuscrucial formanymoderntechnologies.Oxidematerialsarepresentasdielectricelementsin microelectronicdevices(Lorenz etal.,2016;Coll etal.,2019),astransparentlayers inopticalcoatingsandsolarenergyharvestingdevices,theyformcorrosionprotective layersonmetals,actascatalysts,andtheyconferbiocompatibilitytomedicalimplants inthehumanbody.Technologicalprogresssincethesecondhalfofthe20thcentury hasbeenbasedtoalargeextentontheprogressinthinfilmtechnology,amongstwhich oxidethinfilmshaveplayedandareplayingamostprominentrole.Forexample,the microelectronicrevolutionthatledtothecomputerageandtoourpresent-daydigitalsocietyisessentiallyrootedinthemetal-oxide-semiconductorfieldeffecttransistor (MOSFET)deviceelement,inwhichthedielectricpropertiesofthinfilmsofSiO2 as gatedielectricsandofotheroxidelayersincapacitiveelementsareessentialforits functioning.Withtheongoingtrendtowardsminiaturizationofallkindsofdeviceelementsandtheprogressionfromthemicrotechnologytothenanotechnologyareainthe lasttwodecades,newchallengesinthefabricationandcharacterizationofmaterials havearisen.Ultra-thinfilmsofnanometrethickness(nanolayers)withnovelpropertiesaremoreandmorereplacingtheprevious‘thick’micrometerfilms,andother formsofnanostructuredmaterialswithwell-definedshapeandbehaviour(nanoparticles,nanosheets,nanorods)havebecomeofincreasedinterestinmanyscientificand technologicalfields.Inthisbook,wewanttoaddresssomeofthesedevelopmentsand challengesasrelatedtometaloxidematerialsatthenanometrescale.

Itisnecessaryatthisstartingpoint,todefinewhatweactuallyunderstandwithin theframeworkofananomaterial,ananostructure.Thedefinitionisnotunambiguous andhasbeenusedintheliteratureinvariousways.Someauthorsdefineitasa materialthathasatleastinonedimensionasizeof < 100nm.Hereinthisbook, wewanttouseamorerestricteddefinitionandreducethislengthscaletotheorder ofor < 10nm.Inthislatterrange,thescalableregimeofpropertieswithsizeis nolongervalidandnovelbehaviourascomparedtothatofthemacroscopicbulk

phasehastobeconsidered,duetoquantumconfinementeffectsandthesignificance oftheinterfacestotheenvironment.However,weintendtousethisnanostructure definitioninasomewhatpragmaticandflexibleway,dependingonthepropertytobe investigatedanddiscussed,andwewillnotexcludescalesofthecrossoverregionfrom thescalabletothenon-scalableregimes.

Inthisbook,wepresentconceptsandphenomenaofmetaloxidematerialsin nanostructuredforms,thatisultra-thinfilmsofthickness ∼ < 10nmandnanoparticlesofvariousshapes.Eveninbulkform,oxidesarecharacterizedbyagreatvariety ofstoichiometries,structures,andthus,diversephysicalandchemicalproperties.In oxidenanosystems,additionaldegreesoffreedomareprovidedbythevariablesize dimension,thesignificanceofinterfacestosubstratesand/ortheenvironment,andby themorphologyofsurfacesandparticles;theseextradegreesoffreedommaybeused formodifyingpropertiesandfordesigningdesiredfunctionalities.Innanostructured systems,alargeproportionofatomsisatthesurface;thus,surfacepropertiesbecome particularlyimportant.Thisisalsoreflectedinthemethodologythatisemployedfor theexperimentalcharacterization:surfacesciencetechniquesarewidelyusedforobtainingatomicscaleinformationofnanosystemsandtheyarethereforeprominently discussedhereinthisbook.Theprogressinthefabricationofepitaxialoxidethin filmsoncrystallinesubstratesbyvacuum-baseddepositionmethodsduringthelast twodecadeshasopenedupthewaytoprospectiveapplicationsinanall-oxideelectronics(Ramirez,2007),inall-oxideepitaxialthinfilmbatteries(Liang etal.,2019), andinthefabricationofepitaxialoxideheterostructures(BiswasandJeong,2017),the lattersimilartothewell-knownheterostructuresofsemiconductortechnologymaterials.Progressinthewetchemicalpreparationmethodshasenabledthereproducible fabricationofoxidenanoparticlesofvariousformsandshapes.Theirshape-dependent propertiesarefindinguseinchemicalapplicationssuchascatalysisorbiologicalrecognitionsystemsaswellasinoptoelectronicdevices.Thediscussionofepitaxialoxide ultra-thinfilmsandoxidenanoparticleensemblesthusformsafocusinthisbook.

Thesurfacescienceofoxideshasbeentreatedintwopreviousseminalbooksof HenrichandCox(1996)andNoguera(1996).HenrichandCox’sbookisfocussedon thepropertiesofsinglecrystalsurfacesofbulkoxideswithaviewtowardstheadsorptionofmoleculesasafirststageofcatalysis.Noguera’sbookdevelopsconcepts ofstructureandelectronicbehaviourofoxidesurfacesfromamoretheoreticalangle. Bothbooksarerecommendedtoreadersinterestedinthefundamentalpropertiesof oxidesurfaces.Morerecently,PacchioniandValeri(2012)haveeditedanaccountof thescienceandtechnologyofoxideultra-thinfilmsinanumberofimportanttechnologicalapplications.ThecollectionofchaptersinthebookeditedbyNetzerand Fortunelli(2016)considersoxidematerialsatthetwo-dimensionallimit,thatisin (quasi-)two-dimensionalform,notonlyconcentratingonmorefundamentalaspects, butalsopointingoutrelationstoapplications.

Theapproachwehaveadoptedinthisbookattemptstoserveadualpurpose:on theonehand,itintroducesthereadertothefundamentalconceptsofoxidenanosystemsincorporatingboththeoreticalandexperimentalaspects;ontheotherhand,it highlightsthecharacteristicpropertiesofsomeprototypicaloxidenanosystemsfrom aphenomenologicalviewpoint,withsidelongglancesonselectedbenchmarkingappli-

cations.Thebookisorganizedalongthefollowinglines.WebegininChapter2with methodsforthefabricationofoxidethinfilmsandnanoparticles,fromthesurfaceoxidationofbulkmetalsviathinfilmdepositionmethodologiestonanoparticlefabrication methodsinthegasphaseandliquidenvironments.Anintroductionintonucleationand growthconceptsroundsoffthischapteronpreparatoryaspects.InChapter3,experimentalcharacterizationtechniquesandquantumtheoreticalmethodsforgeometric andelectronicstructuredeterminationofoxidesystemsarepresented.Thischapter underlinesthefactthattheprogressinthecharacterizationofnanostructuresandlowdimensionalsystems,aswehavewitnessedduringthelasttwodecades,hasbeenmade possibleonlybythecloseinteractionofexperimentalandtheoreticalstudies.Chapter 4isdevotedtofundamentalpropertiesofoxidethinfilms.Here,intrinsicproperties ofoxidefilmsandtheenvironmentaleffectsintroducedbythepresenceofsubstrates, thatisinterfacialphenomena,arediscussed.Oxidethinfilmsatthetwo-dimensional limit,i.e.oxidesastwo-dimensionalmaterialsandtheircharacteristicnovelphysicalandchemicalproperties,constitutethetopicsofChapter5.Someexperiments,for whichthe‘proofofconcept’exploratorystageforapplicationshasjustbeenovercome, arecitedasexamplesforpotentialfutureapplications.InChapter6,thebasicphysicalconceptsgoverningthepropertiesofoxidenanoparticles—structure,electronic behaviour,andenvironmentaleffects—areinvestigated,bothinthenon-scalableand scalablesizeregimes.Claymineralsareagglomerationsofnaturaloxidenanolayersand nanosheets;theyhavebeenusedforthousandsofyearsinhumanculturesaspottery, buildingmaterialsandinpharmaceuticalapplications.Chapter7givesanintroduction intothesenaturaloxidenanomaterials,discussingstructureandchemicalreactivities ofclaymineralsandtheirinteractionwiththehumidenvironment.Chapter8gives animpressionofthevariousinterdisciplinaryfieldsinwhichoxidenanosystemsare activeandinvestigatedinscienceandtechnology.Thecommonthemeofthediverse topicsinthischapterissurfacechemistryinitswidestsense,involvingelectrontransferprocesses(redoxreactions)asbasicingredients.Heterogeneouscatalysis,oneofthe matureapplicationsofoxidenanoparticlesintheformofhighsurfaceareaoxidepowdercatalystsismentioned,togetherwiththemorerecentphotocatalysis,solidoxide fuelcells,solarenergymaterials,andcorrosionprotection.Thecurrenttrendtothedevelopmentof‘green’nanotechnologiesisreflectedinthesesections.Aprominentplace inChapter8isgiventobiologicalapplicationsofoxidenanosystems,includingthe oxide-mediatedbiocompatibilityofmaterials,diagnosticandtherapeuticproperties ofoxidenanoparticles,biosensing,andtheresponseofbiosystemstoelectricfieldsin ferroelectricoxides.Thebookisconcludedwithageneralsummary,someconclusions andacautiousglimpseintopossiblefuturedevelopmentsinChapter9.Threeappendicesareadded.TheygiveasimpleintroductiontotheprinciplesunderlyingtheWulff constructionandtotheFrenkel–Kontorovamodelofincommensurableinterfaces,as wellasalistoftheacronymsusedinthebook.

Thereferencescitedinthisbookreferoftentoreviewarticlesforintroductory purposes,butimportantkeypublicationsarementionedaswell.Duetothewide rangeofdifferenttopicsandaspectstreatedinthisbook,anexhaustivebibliography isbeyonditsscope.Furtherspecialistliteraturecanbefoundinthecitedreview publicationsandbooks.

Growthofoxidethinfilmsand nanoparticles:Methodsof fabrication

Thefabricationofoxidematerialsintheformofthinfilmsandnanoparticlesisthe keysteptoenablethescientificstudyofoxidesatthenanoscaleandtheirapplicationsinthefieldsofnanoscienceandnanotechnology.Asinotherareasofcondensed matterphysicsandchemistry,theavailabilityofgoodqualitysamplesisaprerequisite fortheexperimentalcharacterizationofthefundamentalpropertiesofnanomaterials,andprogressinimprovingsamplequalityhasoftenledtothediscoveryofnovel andemergentphenomena.ThediscoveryofthequantumHalleffectmaybecitedin thiscontext,whichwasonlypossibleafterthequalityofsemiconductorheterostructuresampleshadreachedacriticalleveloflowdefectdensities(VonKlitzing,1993; VonKlitzing,2005).Goodqualityinsamplesofoxidethinfilmsmeanswell-ordered homogeneouscrystallinelayerswithfewimpuritiesandfewlocalandextendeddefects, whereasitisacontrollableanduniformsizeandshapedistributioninthecaseofoxide nanoparticles.

Thefirstsectionofthischapterisdevotedtotheformationofoxidethinfilmsby oxidationoftheouterlayersofbulksolids,thesecondsectionaddressesmethodologies ofoxidethinfilmdeposition,whereasthethirdsectionpresentsmethodsoffabrication ofoxidenanoparticles.Theforthsectioncontainsanintroductiontothefundamental processesofthinfilmandnanoparticlenucleationandgrowth.

2.1Oxidationofbulksolids

Oxidationinthepresentcontextmeansthechemicalreactionofasolid(metal,alloy orsemiconductor)withanoxidant.Thisinvolvesthetransferofelectronsandthe formationofanewcompound,theoxide,withaconcomitantchangeinthebonding statefrommetallic/covalentto(partly)ionic.Formationofanoxidelayerrequiresthe creationofcationsfromthemetallic(electropositive)element,thedissociationofthe oxidantmolecule(assumingmolecularoxidantssuchasO2 orH2O)atthesurface, andtheformationofoxygenanions.Afterthedirectoxidationoftheoutermostfirst atomiclayersofthesolid,diffusionprocessesinthesolidarerequiredforthemass transportnecessaryforfurtheroxidegrowth.Thediffusionmayinvolvemetalcations

OxideThinFilmsandNanostructures.FalkoP.NetzerandClaudineNoguera,OxfordUniversity Press(2021). c FalkoP.NetzerandClaudineNoguera.DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198834618.003.0002

Growthofoxidethinfilmsandnanoparticles:Methodsoffabrication

Table2.1 Comparisonofmetalandrespectiveoxidecrystalstructures.hcpandfccstructuresstandforhexagonalclosepackedandfacecentredcubic.

MetalStructureOxideStructureSymmetry

MghcpMgORock-saltCubic

Alfcc α-Al2O3

TihcpTiO2

CorundumHexagonal

RutileTetragonal CohcpCoORock-saltCubic NifccNiORock-saltCubic

ZrhcpZrO2 FluoriteCubic

oroxygenanions,dependingonthematerial,andelectronsandholestomaintain chargeneutralityinthegrowingfilm.Thefollowingtreatmentwillberestrictedto thegas-solidoxidationreaction,i.e.theoxidantsareappliedfromthegasphase.The electrochemicalanodicoxidationinaqueousenvironments,whichisofmajorinterest incorrosionprocesses(MarcusandMaurice,2011),willnotbeaddressedhere.

Whileitmayappearthattheoxidationoftheouterregionofanelementalbulksolid isastraightforwardwaytoformanoxidefilm,thisprocedurehasseverallimitations. First,onthematerialsside,itisnotflexibleandisrestrictedtoanoxidefilmgrown onitsownmetal(semiconductor).Thus,oxidefilmsondifferentsupportmaterials,as desirableformanypurposes,requiredepositiontransfertechniques(seeSection2.2).

Second,ithasshortcomingsintermsoftheoxidefilmquality:theoxidationofbulk solidstendstoyieldimperfectfilmswithpoorlong-rangeorder,highdefectdensities, androughfilmmorphologies.However,formanyapplicationsofoxidethinfilms,flat layerswithepitaxiallong-rangeorderandlowdefectdensitiesaredesired.Epitaxial filmgrowth,i.e.thegrowthofacrystallinelayerontopofacrystallinesubstrate, requiresthatthelatticesofthegrowingfilmandthesubstratematchattheirinterface intermsofsymmetryandlatticeparameters.Ingeneral,thelatticematchbetween metalsandtheirownoxidesispoor,preventingtheepitaxialgrowthofoxidefilmson theirparentmetals.ThispointisillustratedinTable2.1,whereafewselectedexamples ofmetalandoxidelatticestructuresarecompared.Forultrathinoxidefilms,thestrict overlayer-substratelatticematchingconditionintermsofcoherentinterfacesmaybe relaxedduetotheflexibilityof(quasi-)two-dimensionaloxidelatticesandthestability ofnovelinterfaceoxidephases,andepitaxialgrowthmaystillbeenabledincasesof significantmismatchofthebulklatticesofoxidesandsubstrates(Oberm¨uller etal., 2017).ThiswillbefurtherdiscussedinChapter5.

Oxidethinfilmsonmetalsmaybetheresultofunintendedcorrosiveprocesses,i.e. oxidationreactionsatmetalsurfacestakingplaceinourenvironmentalatmosphere containingoxygen,water,halogens,orotheraggressiveoxidants.Theformationofrust onironsurfacesisawell-knownphenomenon.Theeffectofthesecorrosionreactions limitsthestabilityofmetalsinevery-daypracticalapplicationsandisanimportant technicalproblem,butcorrosioncanbeinhibitedbyprotectiveoxidelayers(Macdonald,1999).Passivatingoxidelayersoflimitedthicknesscanbegrownconvenientlyas aresultofself-limitedgrowth;characterizedbyhighthermalandmechanicalstability withgoodadherencetotheparentmetal,passivatingoxidelayersmayprotectthe

bulkofthemetallicsubstratefromthecorrosiveenvironment(OlssonandLandolt, 2003).Aluminiumandchromiumoxideforexamplecanbeusedforpassivatingoxide layers.

2.1.1Thermaloxidationofbulkmetalsandsemiconductors

Thegas-solidoxidationreactionatroomtemperaturecommonlystops,afterathin oxidelayerhasbeenformed,duetokineticconstraints(passivation).Atelevatedtemperatures,thickeroxidefilmscanbegrownslowly.Itisconvenienttoseparatethethermalgrowthofoxidesintotworegimes(stages):high-temperatureandlow-temperature growth;thesetworegimesaresynonymouswiththickandthinfilmgrowth,respectively.Inthehigh-temperatureregime,thethermalenergyissufficientforionization anddiffusivetransport,asdescribedbyWagner(1933),resultinginaparabolicgrowth lawforthickfilms.Inthelow-temperaturestage,anelectricfieldacrossthegrowing oxidefilmhasbeeninvokedbyCabreraandMott(1949)topromotediffusiontransport.Thisleadstoalogarithmicgrowthlawforthinfilms.Thequestionofwhatisa thickorathinoxidefilm,orofwhatisahigh-oralow-oxidationtemperature,depends onthematerialsandontheircrystallographicstateandwillnowbediscussed.

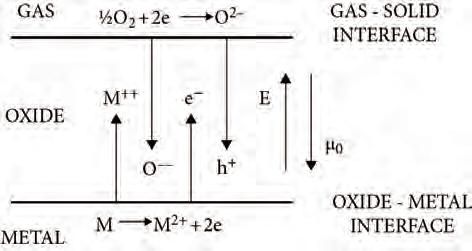

Theelementaryprocessesoccurringduringthegrowthofanoxidefilmaredepicted schematicallyinFig.2.1.Oxygenmoleculesasoxidantsfromthegasphaseareadsorbedatthesurfaceofthesolid,dissociateandbecomeionizedformingO2 anions atthegas-solidinterface.Concomitantly,metalcationsarecreatedatthemetal-oxide interface.Theionsandtheliberatedelectrons(holes)diffuseinagradientofoxygenchemicalpotential µO andelectricfield,eventuallyformingoxidenucleiandthen furthercontributingtotheoxidefilmgrowth.Thefollowingdiscussionoftheoretical considerationsisashortenedversionofthetreatmentgivenbyAtkinson(1985)inhis excellentreviewonoxidefilmgrowth.These‘classical’theoriesofoxidefilmgrowth donotaddresstheatomisticprocessesattheverybeginningoftheoxidationprocess. Ashortdiscussionofthelatterasrevealedbyamoderndensityfunctionaltheory approachwillbegiveninthelastpartofthissection.

Theoryofthickfilmgrowth. Thetheoryofthickoxidefilmgrowthformulatedby Wagner(1933)isaphenomenologicalapproach,whichrelatesthegrowthrateofthe

Fig.2.1 Schematicofionformationandtransportingradientsofchemicalpotentialof oxygen µO andelectricalpotentialacrossagrowingoxidefilm.AdaptedfromAtkinson(1985).

Growthofoxidethinfilmsandnanoparticles:Methodsoffabrication

oxidefilmtotransportpropertiessuchasdiffusioncoefficientsandelectricalconductivities.Thickfilmsheremeansthicknessesoftheorderoforgreaterthan ≈ 1 µm,aswill bediscussed.Althoughsuchthickfilmsarenotthemajortopicsofthisbook,whichis intendedtoconcentrateonnanoscaleobjects,Wagner’stheoryprovidesausefulstartingpointforadiscussionofoxidefilmgrowth.Previousexperimentalobservations haverevealedthatthethicknessofoxidefilms X followsaparabolickinetics:

with kp theparabolicrateconstantand t thetime.Suchparabolickineticsisconsistent withatransportmechanisminagradientofadrivingforce,whichbecomessmaller asfilmthicknessincreases.Thisbecomesapparentbydifferentiatingeqn2.1:

withincreasing X,thegrowthrate dX/dt slowsdown.

Wagner’stheoryisbasedontheassumptionthatdiffusioninthefilmistherate limitingstep;bothionicandelectronictransportsacrossthefilmarenecessaryto providethematerialtransportthroughthefilm(seeFig.2.1).Notethatelectronic transport(electronsandholes)isrequiredtocreateoxygenanionsandmetalcations attherespectiveinterfaces.Sincethediffusingspeciesareelectricallycharged,the diffusionfluxesarecausedbygradientsofthechemicalpotentialandelectricfields, thelattercreatedbytheseparationofcharge.Thediffusioncurrentdensity Ji ofa particleiisgivenby

where Ci istheirconcentration(inparticles/unitvolume), µi thechemicalpotential (µi = kB T ln Ci+const), Di thediffusioncoefficient, qi thecharge,and E theelectric field; kB and T havetheirusualmeaning,Boltzmannconstantandtemperature.The validityofeqn2.3dependsonthevalidityoftheNernst–Einsteinrelation,which describesthediffusionofchargedparticlesintermsoftheirelectricmobility mq and thediffusioncoefficient D:

Thisinturnreliesonthehypothesisofasmallelectricfield E: qEa kB T ,where a istheionicjumpdistance.

Theelectricfieldduringthickfilmgrowthmaybecausedbyambipolardiffusion (i.e.diffusionofparticleswithbothpolarities).Ifmetalcationsaremoremobilein theoxidethanoxygenanions,anewoxideisformedattheoxide/oxygeninterface (gas-solidinterface,seeFig.2.1).Electronsmustalsodiffuseoutwardwiththecations (orholesdiffuseinward)toionizetheoxygenatomsattheinterfacethatbecome subsequentlyincorporatedintotheoxide.Electronsaremoremobilethanions,andan electricfielddevelopsthatspeedsuptheionsandslowsdowntheelectrons;thegassolidinterfacedevelopsanegativeelectricpotentialwithrespecttotheoxide-metal interface.Thesameisalsotrue,ifthefilmgrowsmainlybydiffusionofoxygenanions.

InWagner’stheory,itisassumedthatthesystemisinapseudo-steady-state,i.e. thatthereisnonetelectricalcurrent.Further,itisassumedthatalocalchemical equilibriumexiststhroughoutthefilm.Eliminatingtheelectricfieldtermfromtransportequationslikeeqn2.3andallchemicalpotentialsbut µO,thechemicalpotential ofoxygen,theparabolicrateconstant kp canbeexpressedby:

e isthemodulusoftheelectriccharge, α thestoichiometrycoefficientand N0 the numberofMOα oxidemoleculesperunitvolume. σtot isthetotalelectricalconductivityoftheoxidewith te and tion thefractionsofthetotalconductivityprovided byelectronsandions(transportnumbers),respectively.Theintegrationlimitsineqn 2.5aretheactivitiesofmolecularoxygenatthemetal-oxideinterface a(O2)I andthe oxide-gasinterface a(O2)II

Formostoxides tion te ≈ 1,i.e.theionicconductivityismuchlessthanthe electronicconductivity,andeqn2.5canberecastinto

D aretheself-diffusioncoefficientsofcations(M)andanions(O),and fM and fO are thecorrelationfactorsformetalandoxygenionself-diffusion(fM ≈ fO ≈ 1).The significanceofeqn2.6isthatitexpressesaquantitativerelationbetween kp andthe tracer(self-)diffusioncoefficientsofionsintheoxidefilm,whichareexperimentally accessiblequantities.Thisrelationisphenomenologicalinthatitdoesnotdisclose theatomisticdiffusionmechanism(apartfromthecorrelationfactors fM/O,whichare weaklydependentonit).Thedependenceofthe D dataontheoxygenactivity a(O2) containsinformationonthedefectstructureoftheoxidefilm,andthisisausefulway ofobtainingsuchinformation.

TherangeofvalidityofWagner’smodelrequires,first,thevalidityoftheNernstEinsteinrelationandthussmallelectricfieldsrelativetothethermalenergy kB T . The E fieldfromambipolardiffusionisoftheorder ≈ 100kB T/eX (seeAtkinson (1985)fordetails), X 100a,andthusfilmthickness X 20nm.Second,theclaim oflocalchemicalequilibriumrequireselectricchargeneutralitythroughoutthefilm; this,however,isnotvalidclosetotheinterfaceboundaries.Thesurfacechargesatthe interfacecauseaspace-chargeregionofoppositepolarityextendingintothefilm.The extentofthespace-chargeregionisoftheorderoftheDebye–H¨uckelscreeninglength LD

0k

2Cd (2.7) where and 0 arethedielectricconstantsoftheoxideandvacuum,and Cd isthe totalnumberofelementarychargespervolumeduetochargeddefectsatequilibrium inthebulkoxide.Theassumptionofchargeneutralityisreasonableonlyif X LD

Unfortunately, Cd isnotwellknown,butitcanbeestimatedfromconductivitydata. Aneducatedguessforatypicaloxidewithlowdefectconcentrationssuggeststhatat

LD =

B T

Growthofoxidethinfilmsandnanoparticles:Methodsoffabrication

≈ 500◦C, LD isprobablylessthan1 µm.Theambipolardiffusionisafurthersource ofspacecharge:theadditionalchargesattheinterfacescreatetheelectricfieldinthe film,butalsoaspacechargeduetonon-uniformityeffects.Estimatesoflocalvariations ofthedefectconcentrationindicatethat X LD shouldbeavalidassumptionfor localelectricalneutrality.Takentogether,formostoxidesandgrowthtemperatures largerthan500◦C,Wagner’stheoryshouldbevalidforfilmthickness X> 1 µm.

Theoryofthinfilmgrowth. Foroxidefilmsof X< 1 µmthickness,theelectricalneutralityconceptwithinthefilmisunreliable,andfor X< 20nmtheNernst–Einstein relationisnolongervalid.Thus,thepresenceoflarge E fieldsandlargespacecharges havetobeconsidered.Severaltheorieshavebeenformulated,withacorresponding numberofkineticexpressionsforfilmgrowth:logarithmic,inverselogarithmic,cubic, orparabolic(Atkinson,1985).CabreraandMott’stheory((CabreraandMott,1949)) describestheoxidationinatomictermsandisillustrativeforthepresentdiscussion: electronspassfreelyfromthemetaltotheadsorbedoxygeninanequilibriumelectrochemicalpotential(=Fermilevel)ofthemetalandtheadsorbedlayer,auniform electricfieldiscreatedinthefilmbypositivesurfacechargesonthemetalandnegative chargesfromexcessO2 ionsatthegas-oxideinterface.Thisfielddrivestheslowionic transportacrossthegrowingfilm.Theadsorbedlayerofoxygenionsisinequilibrium withthegasphaseaccordingtothereaction:

Theequilibriumconstantofthisreactionis

n0 isthenumberofexcessO2 ions,i.e.thosecreatedbythegas-surfacereaction, NS thetotalnumberofO2 ionsperunitsurfacearea.Theactivityofelectronswith respecttotheFermilevelis:

with∆φ thevoltageacrossthefilm.Combiningtheseequationsandsolvingfor n0 gives:

arelationbetweentheexcessO2 ions n0 andthevoltageacrossthefilm.Thefilm andthesurfacechargesmayberegardedasasimplecapacitor:

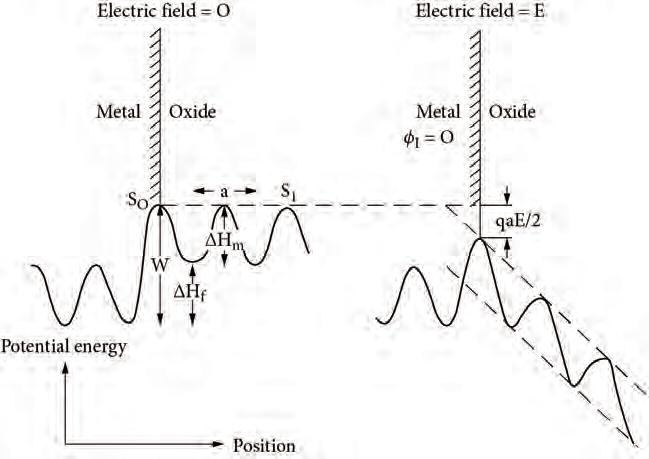

Fig.2.2 Schematicdiagramofthepotentialenergyofaninterstitialmetalionasafunction ofpositionatthemetal-oxideinterface.Theelectricfieldintheoxidefilm,generatedbythe transferofelectronsfrommetaltooxygen,lowerstheenergybarrierforionsmovingintothe oxidefilm.ReprintedfromAtkinson(1985)withpermission.Copyright1985bytheAmerican PhysicalSociety.

Eliminating n0 bysettingeqn2.13=eqn2.14andreformulatingyields:

Sincetypically e∆φ/kB T 1,theleftsideofeqn2.15isdominatedbythefirstterm andthesecondtermcanbeneglected;solvingfor∆φ gives:

Thevoltageacrosstheoxidefilm∆φ isthusmainlydependentontheGibbsfree energy∆G ofreaction2.8andonthetemperature,andlessontheactivityofoxygen inthegasphase a(O2)andthefilmthickness X.Fortypicalvalues,∆φ =1V, = 10, X =10nm,thenumberofexcessO2 ionscanbecalculated(fromeqn2.14)to n0 =2 8 ∗ 1016 m 2,whichisonlyasmallfractionofamonolayer.

Cabrera–Mottassumedthattheratecontrollingstepofoxidefilmgrowthisthe injectionofdefectsintotheoxideatoneoftheinterfaces.Hereweconsideronlythe simplestcaseofoxidedefectsinjectedatthemetal-oxideinterface,intheformofan

Growthofoxidethinfilmsandnanoparticles:Methodsoffabrication

interstitialmetalionM2+.AsillustratedontheleftsideofFig.2.2,theactivation energyforajumpofametalatomintotheoxideis W .Undertheinfluenceofan electricfieldduringoxidefilmgrowth,thebarriersattheinterfacearereducedby qaE/2= qa∆φ/2X (seeFig.2.2,right).InWagner’smodel,theinterfaceisassumed tobeinequilibrium,i.e.thejumpfrequenciestotherightandtotheleftofthebarrier S0 areequal.ForCabrera–Mott,theinterfaceisfarfromequilibrium,i.e.ifthe E field islargeenough,jumpsoccurpredominantlytotheright.Theconditionthatreverse jumps(totheleft)arenegligibleis qaE/2 kB T (i.e.thethermalenergyisinsufficient toovercomethefieldeffect).ThisisthesameconditionastheNernst–Einsteinrelation becominginvalid,anditislikelytobetrueforfilms X< 20nm.

Inthishighfieldlimit,thejumpratecorrespondstoagrowthrate

with ν thevibrationalfrequencyofmetalatomsattheinterface.Thismayberewritten intotheform:

X1 correspondstotheupperlimitofthicknesswithinthevalidityofthebasicassumptions, Di hasthedimensionofadiffusioncoefficient.Equation2.18predicts anoxidationratethatdecreasesexponentiallyastheoxidethickness X increases.If X X1,eqn2.18maybeapproximatelyintegrated:

ThisistheinverselogarithmickineticequationoftheCabrera–Motttheory. XL hasthe meaningofalimitingthickness,abovewhichthegrowthratefallsbelowanarbitrary lowrate.WiththeCabrera–Mottcriterionofanegligiblerateof10 15 ms 1:

for XL = X,theupperlimitofthevalidityofthemodel, T =(W/40kB )definesa criticaltemperature:if T<W/40kB ,theoxidefilmgrowstoalimitingthicknessof XL <X1,butif T>W/40kB ,thefilmcontinuestogrowbeyond X1 andreachesthe parabolicregime.

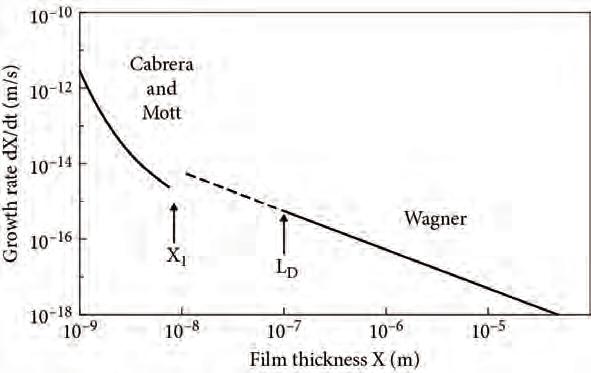

ThetheoriesofWagner,forthickfilms,andofCabrera–Mott,forthinfilms,rely onassumptionsthatareprobablyvalidonlyatthelimitsofverythickandverythin oxidefilms.ToillustratetherangeoftheCabrera–MottandWagnertheories,Fig. 2.3displaysthegrowthrateofahypotheticaloxideasafunctionofthickness,using Cabrera–Mottforthin(X<X1)andWagnerforthick(X>LD and X1)films.The parametersusedhavebeenestimatedforaNiOfilmgrowingbylatticediffusionat 500◦C(Atkinson,1985).Asseenfromtheplots,atthelimitsoftheirvaliditythe Cabrera–MottandWagnertheoriesaremutuallycompatible.

Fig.2.3 Growthrateofahypotheticaloxidefilmasafunctionofthickness,calculatedusing theCabrera–Motttheorywhenthin(X<X1),andofWagnerwhenthick(X>LD and X1).Thespacechargeissignificantonlyfor X>X1.Electricalneutralityisachievedin mostofthefilmintheWagnerregime.TheparametersusedareappropriateforNiOgrowing at500◦C.AfterAtkinson(1985)withpermission.Copyright1985bytheAmericanPhysical Society.

Possibletestsofvariousoxidegrowththeoriesintermsoftheirexperimentally verifiablequantitiesarediscussedindetailbyAtkinson(1985).Wagner’stheorycan bereadilycomparedwithexperimentsanditisinagreementwithfastgrowingoxides athightemperature(e.g.NiO,Fe2O3,Cr2O3,Al2O3,CoO).Oxidegrowthoccursby outwardmetaldiffusion,withtheexceptionofAl2O3,whichappearstoinvolveinward diffusionofoxygen(possiblyalonggrainboundaries).Atintermediatetemperatures, thegrowthpredictedfromthelatticediffusionmodelisseveralordersofmagnitude slowerthanexperimentallyobserved.Apossiblereasonmaybediffusionalonggrain boundaries,whichismuchfasterthandiffusionwithinthelattice.TheCabrera–Mott theoryqualitativelyexplainsmanyobservations,buttherearealsomanyanomalies. Ingeneral,itappearsthatitisdifficulttofitexperimentalgrowthdatatotheoretical kineticexpressionstotestthevarioustheories:ontheonehand,thepredicteddifferencesbetweenthetheoreticalkineticexpressionsforparabolic(Wagner),logarithmic (Cabrera–Mott),cubic,andothertheoriesofgrowtharenotassignificantandthe accuracyofexperimentaldataisinsufficienttoallowasafedistinctionbetweenthe variousgrowthmodels.

Thermaloxidationofsilicon. ThegrowthofSiO2 onsiliconhasbeenenormouslyimportantfortheevolutionofthepresent-daysilicondevicetechnologyanditisworth separatetreatmenthere.ThinlayersofSiO2 areusedasagatedielectricformetaloxide-semiconductor(MOS)devices.SiO2 asadielectricmaterialonsiliconischaracterizedbyanumberofoutstandingpropertiesforelectronicdevicefabrication:itis agoodinsulatorwithhighstability,agoodbarrierlayerfordopantatoms,andthe

Growthofoxidethinfilmsandnanoparticles:Methodsoffabrication

SiO2-Siinterfacefeaturesperfectelectricalbehaviourwithalowdensityofelectronic trapstates(thelatterisduetothesaturationofallSibondsattheinterface).The SiO2-Siinterfacemayberegardedasagiftofnature,onwhichthewholesilicon-based digitalrevolutionthatwehavebeenwitnessingoverthelast60–70yearshasrelied. AnadditionalbenefitoftheSiO2/Sisystemisthatgoodqualityoxidefilmscanbe readilygrownbythermaloxidation.

Theoxidationofsiliconissignificantlydifferentfromtheoxidationofmetals,in thattheoxidegrowsinanamorphousstate.Thisensurestheplanarityoftheoxide layerwithnograinboundaries,whichagainisbeneficialfordevicefabrication.Since thediffusionofSiatomsinSiO2 ismuchslowerthanthediffusionofO2 molecules, theoxidegrowthprocessoccursattheoxide-siliconinterface.Theacceptedgrowth modelofSiO2 onSihasbeenproposedbyDealandGrove(1965)anditresultsina combinedlinear-parabolicgrowthkinetics.ThederivationoftheDeal–Grovemodelis basedonasteady-stateconditionofthreedifferentfluxes.Thegastransportflux F1 isgivenby:

(2.21)

where CG and CS refertothegasandsurfaceconcentrationsofoxygen,respectively, and hG isamasstransfercoefficientderivedfromHenry’slaw.Thediffusionflux throughtheoxide F2 isderivedfromFick’sfirstlaw:

(2.22)

with D thediffusioncoefficient, X theoxidefilmthickness,and Ci theconcentration ofoxygenattheoxide-siliconinterface.Thereactionfluxattheoxide-Siinterface F3 is:

ki istheinterfacereactionconstant.Thesteady-statecondition F1 = F2 = F3 then leadstotheDeal–Groverateequation:

A and B arerateconstantsand τ takesintoaccounttheexistenceofanoxidelayer att=0; τ isthetimecorrespondingtothegrowthofapre-existingoxide,e.g.the so-called‘native’oxidelayer(1–2nminthickness)thatisusedtostabilize(passivate) Siwafers.

Forathickoxidefilm, X 2 AX and X 2 = B(t + τ ):

Thisistheparabolicgrowthregime,with B theparabolicrateconstant.Forathin oxidefilm:

thisisthelinearregimewith B/A thelinearrateconstant. A and B aredetermined experimentally; A isproportionaltothediffusioncoefficient D,and B/A isproportionaltotheinterfacereactionconstant ki.TheDeal–Groveequationthusdescribes

Oxidationofbulksolids 15 anoxidegrowth,whichstartsfast(linear)andslowsdown(parabolic)withincreasing oxidethickness.

Whatisthetransitionregionbetweenthick(X>A)andthin(X 2 <AX)in theDeal–Grovemodel?ExperimentaldataforthedryoxidationofSi(100),i.e.using gasphaseO2,at1000◦C,yieldA=165nm(DealandGrove,1965).Interestingly, theso-calledwetoxidationofsiliconusingwatervapour(Si+2H2O −→ SiO2 +2 H2)ismuchfaster:thecorrespondingA=226nm(DealandGrove,1965).Thishas beenassociatedwiththefasterdiffusionofH2OascomparedtoO2 inSiO2.However, theoxideresultingfromdryoxidationisdenserandofhigherqualityandthedry oxidationprocedureisthususedfordevicefabrication.Intheultrathinlinearregime ofdryoxidation(< 50nm),ithasbeenobservedthattheSiO2 growthisfasterthan predictedbythelinear-parabolicdescriptionofthegrowthofthickerlayers(Massoud etal.,1985a;Massoud etal.,1985b).TheDeal-Grovemodelhasthusbeenrevisited andamorecomplexbehaviourhasbeenrecognized(Massoud etal.,1985c).

2.1.2Oxidationofalloysinglecrystalsurfaces

Theselectiveoxidationofalloysinglecrystalsurfacesisapracticablewaytoproduce well-orderedultrathinoxidefilms.Thismethodofpreparationhasbeenusedmainly forfundamentalstudiesonoxidemodelsurfacesunderultrahighvacuumsurfacesciencetypeconditions.Theinteractionofoxygenwithbinaryalloysurfacesleadsto thepreferentialsegregationofoneofthemetalliccomponentsandtheformationofan oxidesurfacelayer;themetalliccomponentthatismoreeasilyoxidizedformstheoxide overlayer.Theoxidefilmisinitiallydisordered(amorphous),buthigh-temperature annealingpromotescrystallizationandlong-rangeorderingintheoxidelayer.

Employingthismethod,thetransitionmetalaluminides(NiAl,Ni3Al,FeAl)inthe formofsingle-crystalsurfaceshavebeenprimarilyusedtofabricateultrathinordered aluminiumoxidelayers(seethereviewofFranchy(2000)andreferencestherein).The aluminidesthemselveshaveinterestingengineeringapplications,e.g.asmetallization layersinsemiconductorheterostructuredevicesorhigh-temperatureresistantenvironmentalcoatings.Thelatterapplicationisbasedontheveryeffectdiscussedhere, namelytheformationofacompactpassivatingoxidelayerbyselectiveoxidationof theAlcomponent.Alllow-indexsurfacesofNiAlandNi3Al(100),(110),(111)have beenshowntoformultrathin,wellorderedcrystallineAl2O3-typefilmsafterexposure tooxygenandhigh-temperatureannealing(1000–1200K)(Franchy,2000),though withsomedifferencesinthedetailedatomicstructures.TheformationofAloxideis facilitatedbythermodynamics,theheatofformationofAl2O3 beingmuchlargerthan theonefor(∆Hf (Al2O3)= 1690 7kJmol 1 versus∆Hf (NiO)= 240 8kJmol 1 (Lide etal.,2012)).ThegrowthofAl-oxideunderultrahighvacuumconditions(thatis attypicaloxygenpressures ≤ 10 5 mbar)isself-limitedto0.5–1nmthickness,which correspondsroughlytotwoAl-Obilayers.Itwasoriginallythoughtthatthestructures oftheAl-oxidefilmsarederivedfromoneofthepolymorphsofAl2O3 (e.g. α-, γ-,or δ-Al2O3)consistingofessentiallyhexagonalOandAlplanes,butthecomplexatomic structureshaveremainedariddleformorethantenyears.TheAl-oxidestructureon NiAl(110)wasfinallysolvedbyacombinationofatomicallyresolvedscanningtunnellingmicroscopydataandextensivedensityfunctionaltheorycalculations(Kresse

Growthofoxidethinfilmsandnanoparticles:Methodsoffabrication

etal.,2005).Theideaofhexagonaloxygenplanes,assumedpreviouslyfromthestructureofpracticallyallknownAl2O3 bulkphases,hadtobegivenupandhasbeen replacedbyasquareandtriangulararrangementsofoxygenatoms,withtheAlatoms inbetween,slightlybelowtheoxygenlayer,givinganAl4O6Al6O7 stoichiometryof thetwoAl-Obilayers,incontrasttotheusualAl2O3 stoichiometry.Theregistryof thesubstrateandtheoxideisprovidedbytheinterfacialAlatoms,whicharebonded totheNirowsoftheNiAlpartoftheinterface.Subsequently,usingtheirexperiencewiththealuminamodelonNiAl(110),Schmid etal. (2007)havealsosolvedthe structureoftheAl-oxideonNi3Al(111)withasimilarAl-O-Al-Ostackingsequence, involvingsquareandtriangulararrangementofatomsatthesurface,butwithahole intheunitcellreachingdowntotheNi3Alsubstrate.Theseholesarearrangedin anorderedsublatticeandprovideanchoringcentresforthegrowthofmonodisperse metalclusters,makingthisaluminaoverlayeranexcellentnanotemplateforthegrowth ofregulararraysofnanoparticles(Gragnaniello etal.,2012).Theultrathinalumina nanolayerfilmsonNiAlalloysurfacesformedbyhigh-temperatureoxidationarethus structurallyandchemicallyverydifferentfromthebulk-terminatedsurfacesofthe variousAl2O3 phases,andtheyareprototypicalexamplesofso-calledsurfaceoxides, whicharediscussedinthenextsubsection.

Asmentionedpreviously,thegrowthofaluminafilmsonallNiAlalloysurfaces isself-limitedinthicknesstoabouttwoAl-Obilayers(0.5–1nm),iftheoxidationis performedatlowoxygenpressures.Underatmosphericoxygenpressureconditions, thethicknessoftheoxidelayercanbeincreasedbyroughlyafactoroftwo(Franchy, 2000).Interestingly,anincreaseofthealuminathicknessonNi3Al(111)hasalsobeen observedatlowoxygenpressuresundertheinfluenceofmetalnanoparticlesatthe oxidesurface,whichcatalysetheadditionalgrowthofAl-oxideattheoxide-alloy interface(Gragnaniello etal.,2012).Thisindicatesthatthedissociationoftheoxygen moleculesattheouterAl-oxidesurfaceistherate-limitingstepfortheoxidation:metal nanoparticlescaneasilydissociateO2 attheirsurfaceformingadsorbedOspecies, whichcanreadilydiffusethroughtheoxide,inthecaseoftheAl-oxideonNi3Al(111) throughtheholesintheoxidelattice(aspreviouslymentioned),andoxidiseanother Allayerattheoxide-alloyinterface.

TheformationofGa-oxidebyoxidationofaCoGa(100)alloysurface(Franchy, 2000)isanotherexampleofthesuccessofthe‘alloyoxidationroute’foroxideultrathin filmgrowth.AmorphousGa2O3 formedafteroxygenexposureofCoGa(100)at300K crystallizestoordered β-Ga2O3 afterheattreatmentat700K.Again,thethermodynamicheatofformationcondition,∆Hf (Ga2O3)= 1, 815kJmol 1 > ∆Hf (Co3O4) = 905kJmol 1 (Lide etal.,2012),enablestheselectivesurfacesegregationofGa andtheformationofGaoxide.

Theadvantageandsuccessofthe‘alloyoxidationroute’fortheformationofhighly orderedquasi-2-Doxidesascomparedtotheoxidationofthepuremetalsisbasedon thehigh-temperatureannealingstep,whichpromotescrystallizationandlong-range ordering.Metalalloysaremorestableathightemperaturethantheoxideforming metalconstituents,andhigherannealingtemperaturescanbeemployedtoinduce orderingwithoutmeltingthesubstrate.Thisisexemplifiedbythecomparisonofthe meltingpoints: Tm(NiAl)=1955K; Tm(Al)=933K; Tm(Ni)=1728K.

2.1.3Formationofsurfaceoxides

Theterm‘surfaceoxide’hasbeencoinedtodesignateanultrathinoxidephasethat isformedunderthermodynamicconditions,whichareinsufficientfortheformationof abulkoxide.Asurfaceoxidemayberegardedasametastableintermediatebetween achemisorbedoxygenlayeronasubstratesurfaceandthecorrespondingbulkoxide, thusrepresentingaprecursorstagetobulkoxidation.Theatomicarrangementofa surfaceoxideisdistinctlydifferentfromtherespectivebulkoxideandmaybehighly complex(seee.g.thediscussionoftheAl-oxidesintheprecedingsubsection).Surface oxidesasdistinctphaseshavebeendescribedmostlyonsurfacesofthelatetransitionandnoblemetals,suchasRu,Rh,PdorPt(Lundgren etal.,2006).Different surfaceoxidestoichiometriesandstructureshavebeenreportedasafunctionofthermodynamicgrowthparameters(oxygenpressure,substratetemperature).Sincethese latetransitionmetalsareexcellentoxidationcatalysts,surfaceoxidesmayformunder catalyticreactionconditionsandmayactuallybethecatalyticallyactivephases.This hascausedmajorinterestinthecatalyticcommunitytoelucidatethenatureofthese surfaceoxidephases.

Acommonlyobservedstructuremotifofsurfaceoxidesisahexagonaltrilayer stack,whichformsunderoxygenpressureandtemperatureconditionsof10 5–10 6 mbarO2 and500–700Konthe(100)and(111)surfacesofRh,Pd,andPt(O-Rh-O; O-Pd-O;O-Pt-O)withvariousregistrieswithrespecttothesubstrates.Thesesurface oxidetrilayersdifferinstructureandstoichiometryfromtheirrespectiveRh2O3,PdO andPtO2 bulkoxides.

Asmentioned,theformationofasurfaceoxidemaybeconsideredastheinitial stepintheoxidationofabulkmetal.Thisstephasnotbeenaddressedintheolder theoriesofthethermaloxidationofmetalsasdiscussedintheprevioussubsections, butthemorerecentworkofReuter etal. (2002),usinganextensivedensityfunctional theory(DFT)approach,hasgivenanatomisticdescriptionoftheseinitialstagesof oxygenincorporationintothefirstmetallayersofanRusurfaceandthesubsequent nucleationofsurfaceandbulkoxides.Thepathwayfromoxygenadsorptiononthe Ru(0001)surfacetorutilebulkRuO2 ischaracterizedbythreemetastableprecursor stages:i)adsorptionofadenseoxygenmonolayer,ii)formationoftheO-Ru-Otrilayer surfaceoxide,and(iii)transformationoftheoriginaltrilayerviaalateralshiftintoa stackingfaultgeometry.Withincreasingconcentrationofoxygenatthesurface,oxygen isincorporatedintosubsurfacesitesbetweenthefirstandthesecondRulayer,forming patchesofanO-Ru-Otrilayer.Withthegrowthoftrilayerislands,aregistryshiftof thetrilayerintoastackingfaultgeometrywithrespecttotheunderlyingRusubstrate becomesenergeticallyfavourableandthusalateraldisplacementofthetrilayeris predicted.Withcontinuingoxidation,successivetrilayersareformed,whichareonly looselycoupledtoeachother,leadingtoanexpansionoftheouterRulayerdistances. Beyondacriticalthicknessofthetrilayerphase(> 2trilayers),thetransitiontothe RuO2 (110)rutilebulkstructurecaneasilyoccur.

Itappearsthatthistendencytoformsubsurfaceoxygenislands,thatdestabilize themetalsurfaceandformmetastablesurfaceoxidesasprecursorsforastructural phasetransitiontothebulkoxide,isamoregeneralphenomenononmetalsurfaces. Thismechanismprovidesarationalexplanationoftheinitialstagesoftheformation

Growthofoxidethinfilmsandnanoparticles:Methodsoffabrication

ofbulkoxidelayersontopofametal,whosefurthergrowthinthicknesshasbeen investigatedbythe‘classical’theories(Wagner,Cabrera–Mott,andsoon).

2.2Thinfilmdepositionmethodology

Thefabricationofthinfilmsbydepositionrequiresthetransferofatomic(ormolecular)speciesfromatargetmaterialtoasubstratesurface.Thistransfercanbestimulatedthermally,byphotonsorions,oreffectuatedbytransportviaacarriermedium; inthelattercase,precursorcompoundsofthefilmmaterialaretypicallytransported tothesubstrate,whereachemicalreactionformsthedesiredfinalfilmcompound.In thisreactivedepositionmethod,themoleculartransportcanoccurthroughthevapour ortheliquidphase.Aformalandsomewhatarbitraryclassificationofthinfilmdepositionmethodologiesmaydistinguishbetweenphysicalandchemicalmethods(Valeri andBenedetti,2012).Inphysicalmethods,thedepositionisachievedviaaballistictransportinthevapourphaseandtypicallyinavacuumenvironment.Chemical methodsemploycarriergasesforthemoleculartransportoraliquidenvironment.

2.2.1Physicalmethods

Physicalvapourdeposition(PVD),molecularbeamepitaxy(MBE). InPVDor MBE,anatomicormolecularbeamisgeneratedbythermalevaporationofanelementalorcompoundsolidandmadetoimpingeona(heated)substrate.Thetechniqueof MBEwasintroducedbyJohnArthurandAlfredChofromtheBellTelephoneLaboratoriesinthelate1960s(ChoandArthur,1975;Arthur,2002)tofabricateepitaxialthin filmsofcompoundsemiconductorssuchasGaAsbyevaporatingGaandAs4 species (thustheterm‘molecularbeam’):theAs4 unitsdissociateontheheatedsubstrate surfaceandreactwithGaatomstoformtheGaAsfilm.Ultrahighvacuum(UHV) environmentandcleancrystallinesubstratesurfacesarerequiredtoenablethin-film growthwithquasi-idealparameters,i.e.epitaxialsingle-crystallineorder,growthin alayer-by-layerfashionforminganatomicallysharpinterfacetothesubstratewhile maintainingthebulkstructureandstoichiometryofthefilmmaterial.Inpractice, however,manymitigatingfactorsmaypreventthisidealoutcome(Chambers,2000). Today,theMBEtermisusedsynonymouslywithPVDtodenotevapourphasedepositiontechniquesinvolvingthermalevaporationofsubstancesunderUHVandwell controlledgrowthparameters.Thelatterincludeanatomicallydefinedstateofthe substratesurface,controlofthesubstratetemperatureandtheevaporationrate,and aprogrammabledepositionprotocol.‘Reactive’PVDisperformedbyevaporationof anelementinthepresenceofagaseousreactant(oxidant),e.g.ametalinacontrolledoxygenatmosphere.AninterestingvariantoftheMBEtechniquehasbeen reportedrecentlyusingclustermoleculesasprecursorsforoxideultrathinfilmgrowth. Abeamof(WO3)3 molecules,createdbythermalsublimationofWO3 powder,has beendirectedontoametalsingle-crystalsurfaceandtheadsorbed(WO3)3 clusters havebeenmadetocondensebythermaltreatmentintoawell-orderedepitaxialWO3 film(Li etal.,2011).ThisisaverygentlemethodofpreparingultrathinWO3 films, inviewofthehighmeltingtemperatureofWmetal,whichmakesthestandardPVD methodlessconvenient.Itappearsthatthismethodismoregenerallyapplicableby usingothervolatilemolecularoxideclusters(e.g.(MoO3)3 forMoO3 films(Du etal.,

19 2016),andpossiblyotherlatetransitionmetalmaximumvalencycompounds).PVD isthemethodofchoiceforthepreparationofultrathinoxidefilmsforfundamental surfacesciencetypestudies,duetotheUHVenvironmentandtheabilitytoachieve atomicprecisioninthefilmdepositionprocedure.Animportantissueinoxidethinfilm growthisthechoiceofthesubstrate.Thecrystallographicpropertiesofthesubstrate suchaslatticesymmetryandlatticeconstantareessentialingredientsforordered epitaxialfilmgrowth.Thelatticemismatchbetweenthesubstrateandthefilmas definedby m =(af as)/as,withaf andas thefilmandsubstratein-planelattice constants,respectively,shouldbeassmallaspossibletoreduceinterfacialstrain.For af < (>)as thefilmwillbeundertensile(compressive)stressbeforerelaxation.A smallamountofstraincanbemaintainedinepitaxialfilmsbeforeitisreleasedby thecreationofdefects(misfitdislocations)ormorphologicaltransitions(generationof mosaics,tiltingofthesurface,growthmodechange,e.g.fromlayer-by-layertoisland growth).Sincethelatticestraincanmodifythephysicalandchemicalpropertiesof materials(e.g.magneticanisotropy,surfacechemistry),theengineeringofstrainin thinfilmsbyepitaxialgrowthonappropriatesubstratesisaninterestingapproachto designfunctionalbehaviour.Inultrathinfilmsortwo-dimensional(2-D)materials,the properchoiceofthefilmlatticeconstantaf hastobeconsidered:sincethereduction ofdimensionalityfrom3-Dto2-Dtypicallycausesareductionofthein-planelattice constant,theuseofthebulklatticeconstantofthefilmmaterialisinappropriateto determinethelatticemismatch m (ThomasandFortunelli,2010;NetzerandSurnev, 2016).Anestimateofaf ofafree-standinglayerofthefilmmaterialisrequired,which isgenerallynotavailableexperimentallybutisaccessiblebytheoreticalcalculations (ThomasandFortunelli,2010;Barcaro etal.,2010).

Thesubstratecanplayapassiveroleasaninertsupportoranactiverolein oxidethinfilmgrowth.Inthiscontext,thechoiceofmetalversusoxidesubstrate surfaceshastobeconsideredforoxidePVDfilmgrowth.Ontheonehand,thecrystal symmetrymatchiseasiertofindbetweentwooxidesandthinoxidefilmsgrownon oxidesubstratesaremorelikelytoretainabulk-likestructure(Chambers,2000). Ontheotherhand,thepreparationoforderedmetalsurfacesiswellestablishedand thecharacterizationofthegrownoxidefilmsiseasier,sincechargingeffectsresulting fromtheapplicationofcharged-particleprobesarelessprominent.However,themetal surfacemayplayanactiveroleintheoxidegrowth,inparticularinultrathinfilms, supportingkineticallystabilizedmeta-stablephasesasaresultofinteractionsatthe oxide-metalinterface(NetzerandFortunelli,2016).Forveryreactivemetals(e.g.Fe), sharpoxide-metalinterfacesmaynotbeachievable,andintermixingmayoccurat themetal-oxideinterface(thermodynamicbulkphasediagramsofsolubilitymaygive anindicationofitslikeliness).Thegrowthofintermediateinertbufferlayersmaybe necessarytoachievephaseseparationbetweenthemetallicsubstrateandthedesired oxideoverlayer.

ThechoiceofthegaseousoxidantinreactivePVDisdeterminedbythecondition thattheoxidationofmetallicdepositsonthesupportsurfaceshouldbemuchfaster thanthefilmgrowth(Chambers,2000).Formanymetals,molecularO2 canbeeasily dissociatedatthesupportsurfaceandthegrowthfrontandfulfilsthereforethepreviouslymentionedcondition,wherebythechemicalpotentialofoxygen µO determines

Growthofoxidethinfilmsandnanoparticles:Methodsoffabrication

theoxidationstateoftheoxide(incaseoftheexistenceofseveralstableoxidation states).Specieswithhigheroxidationpotentialsuchasatomicoxygen,ozoneO3,or NO2 (formingNO+Oatthesurface)arealternativechoicesofmoreaggressiveoxidantsthathavebeensuccessfullyusedinreactivePVDgrowth.Thepostoxidation procedureofmetallicPVDfilmswithoneofthementionedoxidantsgivesreasonable filmqualitiesforultrathinoxidefilms,butoxidationmayremainincompleteforthicker films.Cyclingofmetalliclayerdepositionfollowedbypostoxidationhasbeenusedto obtainthickerfilms.Finally,high-temperatureannealinginavacuumorinanoxygen atmospherehastobeemphasizedasanimportantsteptoimprovelong-rangeordering andsingle-crystallinequalityinPVDgrownoxidethinfilms.

Ionassisteddeposition–sputterdeposition. Sputteringisaprocess,inwhichatoms areejectedfromatargetorsourcematerialthataredepositedonasubstrateasa resultofbombardmentofthetargetwithhighenergyparticles.Sputterdepositionin itssimplestconfigurationiscarriedoutinavacuumchamber,whichisbackfilledwith alowpressureofraregassuchasargon,adcvoltageisappliedbetweenthetargetand anelectricallyconductingsubstrateonwhichthefilmisdeposited.Thevoltageionizes thegastoformaglowdischargeplasma,consistingofAr+ andelectrons.TheAr+ ions areacceleratedtobombardthetarget,andviamomentumtransfer,targetatomsare sputter-ejected,someofwhicharedepositedonthesubstrate.Inreactivesputtering, mostlyemployedforoxidefilmgrowth,anoxidantgasisaddedtothevacuumchamber thatreactswiththetargetmaterialcloudcreatingamolecularcompound,whichthen becomesthethinfilmcoating.Theprimaryreactioncontrollingthefilmcomposition occursthusatthefilm-growthsurface.Inmagnetronsputtering,aglow-discharge sputterdepositionoccurswithaclosed,crossedelectricandmagneticfield.Various designswithdifferentfieldconfigurationshavebeendescribed(KellyandArnell,2000). Themagneticfieldinfluencestheelectrontrajectoriesenhancingionformationinthe plasmaregionandpreventingthemfrombombardingthesubstrate.Fasterdeposition ratescanthusbeachieved.Foracomprehensivetreatiseofthinfilmsputterdeposition, werefertotheseminalreviewofGreene,whichgivesbothahistoricalaccountandan overviewofrecentdevelopmentsofthetechnique(Greene,2017).

Pulsedlaserdeposition(PLD). Ahigh-powerpulsedlaserbeamisfocusedinsidea vacuumchamberontoatargetmaterialthatisvaporizedinaplasmaplume,containingneutrals,ions,andelectrons,andisdepositedasathinfilmonasubstrate.For depositingoxidefilms,thisprocessiscommonlyperformedinanoxygenbackground atmospheretoensurestoichiometrictransferofthematerialfromthetargettothe substrate.Thephysicalphenomenaoflaser-targetinteractionarecomplex,consisting ofelectronicandthermalexcitationsandevaporation,ablation,andplasmaformation processes.Keydepositionparametersaresubstratetemperature,laserenergy,laser pulserepetitionrate,andtheambientgaspressure,whichhavetobefinelytunedto achievegoodqualityfilms.TheoutstandingfeatureofPLDistheabilitytoablate practicallyanytargetmaterialandtocontrolthematerials’stoichiometry.Sinceno surfacesegregationinthetargetmaterialtakesplaceduringtheshortevaporation phase,acongruenttransferofthetargetcompoundmaterialtothesubstratesurface ispossible.PLDisthusparticularlysuitedforthefabricationofthinfilmsofcomplex