Oxford Textbook of Interventional Cardiology

SECOND EDITION

Edited by Simon Redwood

Nick Curzen and Adrian Banning

1

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP,

United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Oxford University Press 2018

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

First Edition published in 2010

Second Edition published in 2018

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018943513

ISBN 978–0–19–875415–2

Printed in Great Britain by Bell & Bain Ltd., Glasgow

Oxford University Press makes no representation, express or implied, that the drug dosages in this book are correct. Readers must therefore always check the product information and clinical procedures with the most up-to-date published product information and data sheets provided by the manufacturers and the most recent codes of conduct and safety regulations. The authors and the publishers do not accept responsibility or legal liability for any errors in the text or for the misuse or misapplication of material in this work. Except where otherwise stated, drug dosages and recommendations are for the non-pregnant adult who is not breast-feeding

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

List of contributors ix

SECTION 1

Background and Basics

1 The epidemiology and pathophysiology of coronary artery disease 3

Robert Henderson and Richard Varcoe

2 The history of interventional cardiology 15

Toby Rogers, Kenneth Kent, and Augusto D. Pichard

3 Risk assessment and analysis of outcomes 25

Peter F. Ludman

4 Vascular access: femoral versus radial 49

Andrew Wiper and David H. Roberts

5 Radiation and percutaneous coronary intervention 65

Gurbir Bhatia and James Nolan

6 The ‘golden rules’ of percutaneous coronary intervention 75

Rod Stables

7 Care following percutaneous coronary intervention 81

Kevin O’Gallagher, Jonathan Byrne, and Philip MacCarthy

8 Trial design and interpretation in interventional cardiology: why is evidence-based medicine important? 91

Ayman Al-Saleh and Sanjit Jolly

SECTION 2

Percutaneous Coronary Interventionrelated Imaging

9 Angiography: indications and limitations 99

David Adlam, Annette Maznyczka, and Bernard Prendergast

10 Coronary physiology in clinical practice 127

Olivier Muller, Stephane Fournier, and Bernard De Bruyne

11 The role of intravascular ultrasound in percutaneous coronary intervention 145

Kozo Okada, Yasuhiro Honda, and Peter J. Fitzgerald

12 Intravascular ultrasound and optical coherence tomography in percutaneous coronary intervention 171

Ravinay Bhindi, Usaid K. Allahwala, and Keith M. Channon

13 Cardiac computed tomography for the interventionalist 177

Adriaan Coenen, Laurens E. Swart, Ricardo P. J. Budde, and Koen Nieman

14 Cardiovascular magnetic resonance 191

Theodoros D. Karamitsos and Stefan Neubauer

SECTION 3

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention by Clinical Syndrome

15 Stable coronary disease: medical therapy versus percutaneous coronary intervention versus surgery 211

Vasim Farooq and Patrick W. Serruys

16 Percutaneous coronary intervention in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome 235

Bashir Alaour, Michael Mahmoudi, and Nick Curzen

17 Primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction 251

Zulfiquar Adam and Mark A. de Belder

18 Percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with impaired left ventricular function 273

Divaka Perera and Natalia Briceno

SECTION 4

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention by Lesion and Patient Subsets

19 Coronary bifurcation stenting: state of the art 287

Yves Louvard, Philippe Garot, Thomas Hovasse, Bernard Chevalier, and Thierry Lefèvre

20 Percutaneous coronary intervention for left main coronary artery stenosis 305

Michael Mahmoudi, Nick Curzen, Christine Hughes, Bruno Farah, and Jean Fajadet

21 Chronic total occlusions 315

Colm G. Hanratty, James C. Spratt, and Simon J. Walsh

22 Revascularization in patients with diabetes mellitus 337

George Kassimis and Adrian Banning

23 Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: role of percutaneous coronary intervention 351

Peter Radsel and Marko Noc

SECTION 5

Adjunctive Drug Therapies in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

24 Oral antiplatelet therapies in percutaneous coronary intervention 363

Vikram Khanna, Tony Gershlick, and Nick Curzen

25 Current status of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors 381

Tim Lockie

26 The role of bivalirudin in percutaneous coronary intervention 401

Stefanie Schüpke, Steffen Massberg, and Adnan Kastrati

27 Optimal medical therapy in percutaneous coronary intervention patients: statins and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors as disease-modifying agents 417

Simon J. Corbett and Nick Curzen

28 New oral anticoagulants: the evidence base and role in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention 433

Mikhail S. Dzeshka, Richard A. Brown, and Gregory Y. H. Lip

SECTION 6

Complications of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

29 Contrast-induced acute kidney injury 447

Peter A. McCullough

30 In-stent restenosis in the drug-eluting stent era 453

Jaya Chandrasekhar, Adriano Caixeta, Philippe Généreux, George Dangas, and Roxana Mehran

31 Stent thrombosis 473

Nikesh Malik, Amerjeet Banning, and Tony Gershlick

32 Stent loss and retrieval 501

Mrinal Saha and Adam de Belder

33 Coronary artery perforation 511

Mark Gunning and Chee Wah Khoo

SECTION 7

Special Devices in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

34 Rotational atherectomy 525

Adam de Belder, Martyn Thomas, and Emanuele Barbato

35 Laser 535

Peter O’Kane and Simon Redwood

36 No-reflow in native coronaries and vein grafts: the role of drugs and distal protection 557

Giovanni Luigi De Maria and Adrian Banning

37 Bioresorbable vascular scaffolds 569

Adam J. Brown and Nick E. J. West

38 Access routes and the transcatheter aortic valve implantation procedure 583

Corrado Tamburino, Claudia Ina Tamburino, and Sebastiano Immè

39 Selection of transcatheter aortic valve implantation prostheses 589

Mohamed Abdel-Wahab and John Jose

40 Transcatheter aortic valve implantation and the management of coronary artery disease 601

Muhammed Zeeshan Khawaja and Simon Redwood

41 Transcatheter mitral valve repair 607

Michael Bellamy and Christopher Baker

42 Transcatheter mitral valve replacement 629

Ricardo Boix Garibo, Mohsin Uzzaman, Michael Ghosh-Dastidar, and Vinayak Bapat

SECTION 8

Non-coronary Percutaneous Interventions

43 Percutaneous device closure of atrial septal defect and patent foramen ovale 641

Patrick A. Calvert, Bushra S. Rana, Roland Hilling-Smith, and David Hildick-Smith

44 Mitral balloon valvuloplasty 657

Alec Vahanian, Dominique Himbert, Eric Brochet, Grégory Ducrocq, and Bernard Iung

45 Alcohol septal ablation for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy 669

Charles Knight, Saidi Mohiddin, and Constantinos O’Mahony

46 Carotid artery stenting 681

Iqbal Malik and Mohamed Hamady

47 Left atrial appendage occlusion 703

Sandeep Panikker, Tim Betts, and Milena Leo

SECTION 9

The Future

48 Novel device therapies for resistant hypertension 717

Kenneth Chan, Manish Saxena, and Melvin D. Lobo

49 Robotic percutaneous coronary intervention 731

Giora Weisz

50 Stem cell delivery and therapy 737

Fizzah Choudry and Anthony Mathur

Index 751

List of contributors

Mohamed Abdel-Wahab Segeberger Kliniken GmbH (Academic Teaching Hospital of the Universities of Kiel, Lübeck and Hamburg), Bad Segeberg, Germany

Zulfiquar Adam The James Cook University Hospital, Middlesbrough, UK

David Adlam Cardiovascular Research Centre, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK

Bashir Alaour Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK

Usaid K. Allahwala Northern Clinical School, University of Sydney, Australia

Ayman Al-Saleh Department of Medicine, McMaster University, Ontario, Canada; Department of Cardiology, King Saud university, Saudi Arabia

Christopher Baker Imperial Healthcare NHS Trust, Hammersmith Hospital, London, UK

Adrian Banning John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK

Amerjeet Banning St George’s Hospital Medical School, London, UK

Vinayak Bapat St Thomas’ Hospital, London, UK

Emanuele Barbato Cardiovascular Center Aalst, Aalst, Belgium

Michael Bellamy Imperial Healthcare NHS Trust, Hammersmith Hospital, London, UK

Tim Betts John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK

Gurbir Bhatia Birmingham Heartlands Hospital, UK

Ravinay Bhindi Northern Clinical School, University of Sydney, Australia

Ricardo Boix Garibo St Thomas’ Hospital, London, UK

Natalia Briceno Cardiovascular Clinical Academic Group, St Thomas’ Hospital, London, UK

Eric Brochet Cardiology Department, Bichat Hospital, University Paris VII, Paris, France

Adam J. Brown Monash Cardiovascular Research Centre, Monash University & MonashHeart, Melbourne, Australia

Richard A. Brown Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK

Ricardo P. J. Budde Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

Jonathan Byrne King’s College Hospital, London, UK

Adriano Caixeta Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil

Patrick A. Calvert Royal Papworth Hospital, Cambridge, UK

Kenneth Chan University College London, Royal Free Hospital, London, UK

Jaya Chandrasekhar Ichahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai, New York, USA

Keith M. Channon Radcliffe Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Bernard Chevalier Institut Cardiovasculaire Paris Sud, Massy, France

Fizzah Choudry Barts Heart Centre, St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, UK

Adriaan Coenen Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

Simon J. Corbett University Hospital Southampton, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK

Nick Curzen Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK

George Dangas Zena and Michael A. Weiner Cardiovascular Institute, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, USA

Adam de Belder Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust, UK

Mark A. de Belder The James Cook University Hospital, Middlesbrough, UK

Bernard De Bruyne Cardiovascular Center Aalst, Aalst, Belgium

Giovanni Luigi De Maria John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK

Grégory Ducrocq Cardiology Department, Bichat Hospital, University Paris VII, Paris, France

Mikhail S. Dzeshka Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK, and Grodno State Medical University, Grodno, Belarus

Jean Fajadet Clinique Pasteur, Toulouse, France

Bruno Farah Clinique Pasteur, Toulouse, France

Vasim Farooq St George’s Hospital, London, UK

Peter J. Fitzgerald Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, California, USA

Stephane Fournier Department of Cardiology, University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland

Philippe Garot Institut Cardiovasculaire Paris Sud, Massy, France

Philippe Généreux Morristown Medical Centre, New Jersey, USA

Tony Gershlick Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK

Michael Ghosh-Dastidar St Thomas’ Hospital, London, UK

Mark Gunning Royal Stoke University Hospital, UK

Mohamed Hamady Imperial Healthcare NHS Trust, Hammersmith Hospital, London, UK

Colm G. Hanratty Belfast Health and Social Care Trust, Belfast, UK

Robert Henderson Nottingham University Hospitals, Nottingham, UK

David Hildick-Smith Royal Sussex County Hospital, Brighton, UK

Roland Hilling-Smith Queensland Cardiovascular Group, Mater Hospital, Brisbane, Australia

Dominique Himbert Cardiology Department, Bichat Hospital, University Paris VII, Paris, France

Yasuhiro Honda Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, California, USA

Thomas Hovasse Institut Cardiovasculaire Paris Sud, Massy, France

Christine Hughes Clinique Pasteur, Toulouse, France

Sebastiano Immè Ferrarotto Hospital, University of Catania, Catania, Italy

Bernard Iung Cardiology Department, Bichat Hospital, University Paris VII, Paris, France

Sanjit Jolly Department of Medicine, McMaster University, Ontario, Canada

John Jose Segeberger Kliniken GmbH (Academic Teaching Hospital of the Universities of Kiel, Lübeck and Hamburg), Bad Segeberg, Germany

Theodoros D. Karamitsos Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

George Kassimis Cheltenham General Hospital, Cheltenham, UK

Adnan Kastrati Deutsches Herzzentrum München, Technische Universität, Munich, Germany

Kenneth Kent Medstar Heart Institute, Washington, District of Columbia, USA

Vikram Khanna Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK

Charles Knight Barts Heart Centre, St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, UK

Thierry Lefèvre Institut Cardiovasculaire Paris Sud, Massy, France

Gregory Y. H. Lip Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK, and Aalborg Thrombosis Research Unit, Department of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health, Aalborg University, Aalborg, Denmark

Milena Leo Cardiac Electrophysiology Research Fellow, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, UK

Melvin D. Lobo William Harvey Research Institute, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK

Tim Lockie Royal Free Hospital, London, UK

Yves Louvard Institut Cardiovasculaire Paris Sud, Massy, France

Peter F. Ludman Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, Birmingham, UK

Philip MacCarthy King’s College Hospital, London, UK

Michael Mahmoudi Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK

Iqbal Malik Imperial Healthcare NHS Trust, Hammersmith Hospital, London, UK

Nikesh Malik University of Leicester, Leicester, UK

Steffen Massberg Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Munich, Germany

Anthony Mathur Barts Heart Centre, St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, UK

Annette Maznyczka King’s College Hospital, London, UK

Peter A. McCullough Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, USA

Roxana Mehran Zena and Michael A. Weiner Cardiovascular Institute, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, USA

Saidi Mohiddin Barts Heart Centre, St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, UK

Olivier Muller Department of Cardiology, University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland

Stefan Neubauer Oxford Centre for Clinical Magnetic Resonance Research, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK

Koen Nieman Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, USA

Marko Noc Center for Intensive Internal Medicine, University Medical Center, Ljubljana, Slovenia

James Nolan Royal Stoke University Hospital, Stoke-on-Trent, UK

Kevin O’Gallagher King’s College Hospital, London, UK

Peter O’Kane Royal Bournemouth Hospital, Bournemouth, UK

Constantinos O’Mahony Barts Heart Centre, St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, UK

Kozo Okada Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, California, USA

Sandeep Panikker Royal Brompton Hospital, London, UK

Divaka Perera Cardiovascular Clinical Academic Group, St Thomas’ Hospital, London, UK

Augusto D. Pichard Medstar Heart Institute, Washington, District of Columbia, USA

Bernard Prendergast St Thomas’ Hospital, London, UK

Peter Radsel Center for Intensive Internal Medicine, University Medical Center, Ljubljana, Slovenia

Bushra S. Rana Royal Papworth Hospital, Cambridge, UK

Simon Redwood King’s College London, St Thomas’ Hospital, London, UK

David H. Roberts Lancashire Cardiac Centre, Blackpool Victoria Hospital, Blackpool, UK

Toby Rogers Medstar Heart Institute, Washington, District of Columbia, USA

Mrinal Saha Consultant Cardiologist, Cheltenham and Gloucester Hospitals NHS Trust, UK

Manish Saxena Barts Heart Centre, Barts Health NHS Trust, London, UK

Stefanie Schüpke Deutsches Herzzentrum München, Technische Universität, Munich, Germany

Patrick W. Serruys Thoraxcenter, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

James C. Spratt Belfast Health and Social Care Trust, Belfast, UK

Rod Stables Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital, Liverpool, UK

Laurens E. Swart Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

Claudia Ina Tamburino Ferrarotto Hospital, University of Catania, Catania, Italy

Corrado Tamburino Ferrarotto Hospital, University of Catania, Catania, Italy

Martyn Thomas St Thomas’ Hospital, London, UK

Mohsin Uzzaman Birmingham Children’s Hospital, Birmingham, UK

Alec Vahanian Cardiology Department, Bichat Hospital, University Paris VII, Paris, France

Richard Varcoe Nottingham University Hospitals, Nottingham, UK

Chee Wah Khoo Royal Stoke University Hospital, UK

Simon J. Walsh Belfast Health and Social Care Trust, Belfast, UK

Giora Weisz Montefiore-Einstein Center for Heart and Vascular Care, New York, USA

Nick E. J. West Royal Papworth Hospital, Cambridge, UK

Andrew Wiper Lancashire Cardiac Centre, Blackpool, UK

Muhammed Zeeshan Khawaja Guy’s and Thomas’ NHS Hospitals Foundation Trust, London, UK

The epidemiology and pathophysiology of coronary artery disease

Robert Henderson and Richard Varcoe

Epidemiology of coronary heart disease

Advances in the prevention and treatment of ischaemic heart disease (IHD) have led to significant improvements in prognosis and quality of life. However, the ageing and growth of populations has led to an increase in the total number of deaths, and IHD remains a leading global cause of premature death and disability. From 1990 to 2013 age-standardized global death rates from IHD fell from 177·3 to 137·8 per 100,000, but the total number of deaths due to IHD increased from 5.7 million to 8.1 million. Coronary heart disease (CHD) has risen from fourth to first in the rank of causes of global years of life lost (1) and is projected to remain as the leading cause of death, accounting for 13.4% of all deaths in 2030 (2).

Mortality

In the UK age-standardized death rates from CHD have declined over several decades. From 1974 to 2013, age-standardized CHD death rates declined by 73% in those dying at any age and 81% for those dying before age 75. Nevertheless, CHD remains the biggest single cause of death in the UK, accounting for around one in seven deaths in men and one in ten deaths in women, and in 2014 was responsible for around 22,300 deaths under the age of 75 years (3).

In the USA annual CHD mortality declined by 39.2% from 2000 to 2010 (the actual number of deaths fell by only 26.3%), but in 2010 CHD accounted for one in six of all deaths (4).

In high-income countries there are substantial regional, social, and ethnic variations in coronary disease-associated mortality. For example, in the UK in 2011–13 the age-standardized CHD death rate in Scotland was 45% higher overall and 72% higher for premature deaths than the rates for south-east England. Death rates from CHD increase during the winter months, and in 2012–13 the winter CHD mortality in England was 19% higher than at other times of the year (3).

In recent years the decline in coronary mortality in high-income countries has been slower in younger than in older age groups. For example, in the UK from 1997 to 2006 there was a 46% fall in CHD mortality amongst men aged 55–64 years but only a 22% fall amongst men aged 35–44 years (5). In the USA the decline in ageadjusted coronary mortality from 1980 to 2002 slowed markedly

in adults aged 35–54 years. Moreover, since 1997 the mortality rate among women aged 35–44 has been increasing by about 1.3% per year (6).

The decline in the rate of death from cardiovascular disease in several high-income countries has been attributed to reductions in risk factors and improved management of cardiovascular disease (7). It has been estimated that 58% of the decline in coronary mortality in the UK between 1981 and 2000 was attributable to reductions in major risk factors, principally smoking, but the remaining 42% was explained by treatment of individuals, including secondary prevention (8). In the USA 47% of the reduction in CHD mortality from 1980 to 2000 has been attributed to treatments and 44% to modification of risk factors, but these reductions were partially offset by a rise in mortality attributable to increases in body mass index and diabetes prevalence (9). The World Health Organization (WHO) MONICA project examined temporal trends in cardiovascular mortality over the 1980s and 1990s in 21 countries, and demonstrated a strong link between improved care for patients with myocardial infarction and the decline in coronary mortality (10). An investigation into the potential impact of various preventative and interventional strategies on CHD-related mortality in the USA estimated that delivery of ‘perfect care’ (through the modification of risk factors and use of all effective therapies) to a hypothetical population (aged 30–84 years) could prevent or postpone around 75% of cardiac deaths (11).

Globally, IHD mortality rates vary more than 20-fold between countries. In high-income countries age-standardized IHD mortality has been steadily declining over several decades, but population growth and ageing have maintained a high disease burden. By contrast, in some low- and middle-income countries IHD mortality rates are stable or are increasing, especially amongst younger adults adopting urbanized lifestyles. The highest IHD mortality rates are reported in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, and lowand middle-income countries now account for more than 80% of global IHD deaths (12–14) (Fig 1.1).

Age-standardized IHD disability-adjusted life years (DALYs— years of life lost to premature deaths and years lived with non-fatal disease or disability) decreased in most countries between 1990 and 2010, but increased in several countries in Eastern Europe and Central and South Asia. In 2010 around two-thirds of IHD DALYs

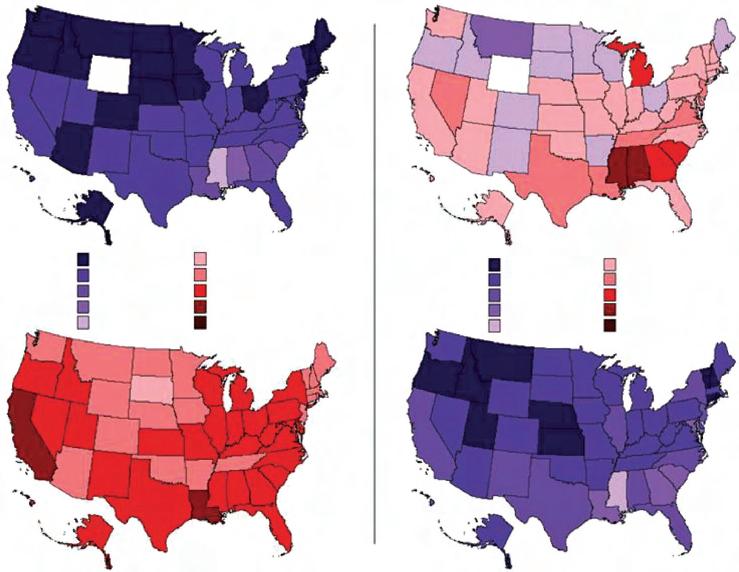

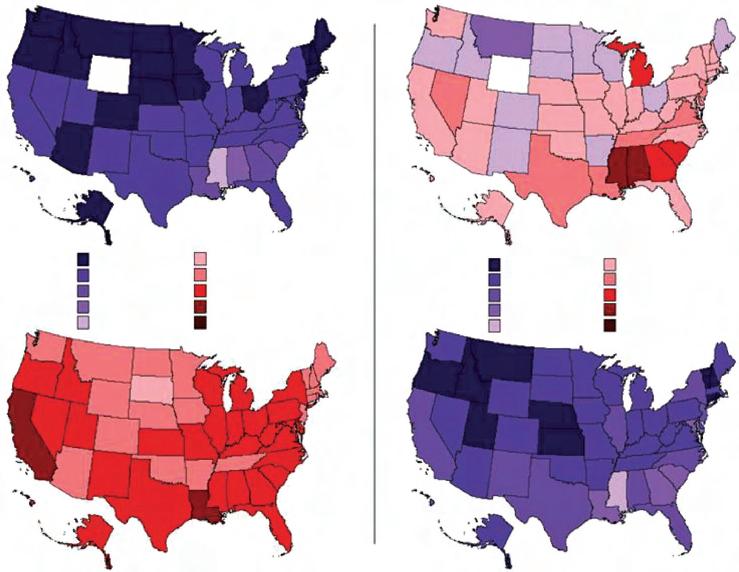

Figure 1.1 Map of age-standardized ischaemic heart disease mortality rate per 100,000 persons in 21 world regions, 2010; the Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Reproduced from Moran A et al. 'The Global Burden of Ischemic Heart Disease in 1990 and 2010'. Circulation (2014) 129:1483 with permission from the Wolters Kluwer Health, inc.

impacted middle-income countries, where young adults were more likely to develop IHD (12, 15) (Fig 1.2).

Morbidity

Coronary artery disease can present with a wide range of clinical syndromes, including stable angina, acute coronary syndrome, heart failure, arrhythmia, and death. Estimating the incidence and prevalence of coronary disease-related morbidity is therefore

challenging and is confounded by changing definitions and diagnostic criteria over time (16, 17).

Acute coronary syndromes, including unstable angina and myocardial infarction (with and without ST-segment elevation on the electrocardiogram), present a major health burden on industrialized societies. As with CHD mortality there are large regional, socioeconomic, and ethnic variations in the incidence and prevalence of myocardial infarction. The reported incidence and prevalence of myocardial infarction is higher in men than in women and increases with age. The Health Survey for England 2006 reported that 4.1% of all men and 1.7% of all women in the UK have had a myocardial infarct (5). In 2011 the prevalence of myocardial infarction in the UK was estimated to be 1.7% for men of all ages and 1% for women of all ages (3). In the USA in 2009–12 the prevalence of myocardial infarction in adults aged 20 or over was estimated at 2.8%, with a prevalence of any coronary disease of 7.8% (18).

In Scotland in 2000 there were over 9000 admissions to hospital with suspected acute coronary syndrome per million population, which accounted for 19% of all emergency hospitalizations and 12% of medical bed days (19). A decrease in the ratio of ST-elevation to non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction has been reported, but whether this is due to a real change in disease prevalence, an effect of treatment, or a change in case recognition is unknown (20).

Figure 1.2 World Bank income category composition of absolute numbers of ischaemic heart disease (IHD) disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in males and females in 2010; the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors 2010 Study.

Reproduced from Moran et al ‘Variations in ischemic heart disease burden by age, country, and income: the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors 2010 study’. Global Heart 9:1 (2014) 91–99 with permission from Elsevier.

The incidence and prevalence of stable coronary disease is difficult to estimate. The incidence of angina in the UK is approximately 96,000 new cases a year, with a higher rate amongst men than women (5). In 2011 the prevalence of angina was estimated to be 3.9% amongst men and 2.5% amongst women (3).

Risk factors

The INTERHEART study investigated various risk factors for myocardial infarction in 15,152 cases in 52 countries, who were matched

to 14,820 controls with no history of heart disease. The mean age of first presentation with myocardial infarction was 8 years younger in men than women and 10 years younger in Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia than the rest of the world. Nine easily measured and potentially modifiable risk factors for myocardial infarction were identified, including smoking, hypertension, diabetes, waist to hip ratio, low daily fruit and vegetable consumption, physical inactivity, overconsumption of alcohol, abnormal blood lipid levels, and psychosocial factors. The effect of these risk factors was consistent in both genders and across different ethnic groups and geographic regions. Collectively, the nine risk factors accounted for 90% of the population-attributable risk for myocardial infarction in men and 94% in women (21).

These risk factors have been incorporated into a risk score, which has been validated in a large cohort from 21 countries (22). The risk factor burden is lower in low-income countries than in middle- or high-income countries, but paradoxically the rates of major adverse cardiovascular events are higher in low-income countries than in middle- or high-income countries. It has been suggested that the high-risk factor burden in high-income countries is mitigated by preventive medications and revascularization procedures, which are substantially more common in high-income than in middle- or low-income countries (23).

Tobacco use, perhaps the most important modifiable risk factor, is associated with a nearly threefold increase in the odds of myocardial infarction (odds ratio [OR] for current smokers 2.95, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.77–3.14 versus never smokers). This increase in risk of myocardial infarction falls after quitting smoking

(OR at 3 years 1.87, CI 1.55–2.24) but remains elevated even after 20 or more years of abstinence (OR 1.22, CI 1.09–1.37). These data suggest that the greatest reduction in global CHD risk could be achieved by preventing smoking and by smoking cessation programmes (24).

A meta-analysis of data from 61 prospective observational studies involving almost 900,000 adults, mostly from Western Europe or North America, confirmed a strong positive relationship between total serum cholesterol and coronary mortality, irrespective of age and the level of blood pressure. Of various simple indices involving measurement of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels, the ratio total/HDL cholesterol was the strongest predictor of coronary mortality (25). Randomized trials of just a few years treatment with 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG CoA) reductase inhibitors (statins) have shown that lowering LDL cholesterol by about 1.5 mmol/L reduces the incidence of coronary events by about a third (26).

Global reductions in other modifiable risk factors also have the potential to prevent cardiovascular events, but lowering rates of hypertension, obesity, and diabetes will be challenging. Epidemiological evidence suggests that throughout middle and old age usual blood pressure is strongly and directly related to vascular (and total) mortality without any evidence of a threshold down to at least 115/75 mmHg (27). In the USA, however, from 2001 to 2003 state-level age-standardized prevalence of uncontrolled hypertension was estimated to range from 15% to 21% amongst men and from 21% to 26% amongst women (28) (Fig 1.3). Similarly, there

Figure 1.3 Age-standardized prevalence (in percentage) of uncontrolled hypertension in the USA from 1988 to 1992 and from 2001 to 2003 (men and women ≥60 years of age). Hypertension control decreased in women between the two study periods. Reproduced with permission from Ezzati M, Oza S, Danaei G, Murray CJ. Trends and cardiovascular mortality effects of state-level blood pressure and uncontrolled hypertension in the United States. Circulation 2008 Feb 19; 117(7):905–14.

is robust evidence that an increase in body mass index of 5 kg/m2 is associated with about a 40% increase in vascular mortality (29), but from 1999 to 2006 the high prevalence of childhood obesity in the USA remained unchanged (30). Nevertheless, relatively modest downward shifts in the population distribution of modifiable cardiovascular risk factors may have substantial effects on disease prevalence, particularly when compared with treatment strategies directed at high-risk individuals (31).

Pathophysiology

Atherothrombosis

Atherothrombosis, defined as atherosclerosis with superimposed thrombosis, is the principal pathological process underlying the majority of clinical cardiovascular events. Atherosclerosis is a systemic process that involves large and medium-sized elastic and muscular arteries and typically affects the aorta and coronary, carotid, and peripheral vessels. The epicardial coronary arteries are particularly susceptible, but other arteries, including the intramyocardial arteries, are rarely affected.

Atherosclerosis starts in childhood, progresses silently through early adult life, and often manifests in later decades with ischaemia or infarction of the heart, brain, or extremities. The disease is characterized by the development of focal atherosclerotic plaques within the intimal layer of the arterial wall that consist of cells, connective tissue, lipids, and debris. The cellular constituents include endothelial and smooth muscle cells from the vessel wall, and inflammatory and immune cells derived from the circulating blood. As the disease progresses individual plaque morphology may change abruptly because of plaque rupture and superimposed thrombosis. In addition, secondary changes may develop in the media and adventitia. As a consequence there may be marked heterogeneity in plaque morphology in different vascular territories, even in the same individual. The complex molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the atherosclerotic disease process are incompletely understood, but it is now recognized that atherosclerosis is an active process involving interplay of cardiovascular risk factors, vascular biology, and chronic inflammation.

Endothelial activation

The vascular endothelium, the innermost cellular layer of blood vessels, has a key role in vascular homeostasis and is critically involved in the development of atherosclerotic disease. In health the endothelium produces a wide range of locally active substances that regulate contractile, secretory, and mitogenic functions of the vessel wall, and influence blood coagulation.

Endothelial physiology

The importance of the endothelium was first demonstrated in studies of vascular tone (32), but it is now recognized that the endothelium releases a range of autocrine and paracrine mediators that control vascular physiology and response to injury. Nitric oxide (NO), the principal endothelium-derived relaxing factor, plays a key role in the maintenance of vascular tone and endothelial reactivity. NO is synthesized from the amino acid L-arginine by the action of endothelial nitric oxide synthetase (eNOS). This enzyme requires a critical cofactor, tetrahydrobiopterin, to facilitate endothelial NO production. Following release from

endothelial cells, NO diffuses into medial smooth muscle cells and activates guanylate cyclase, which results in cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)-mediated vasodilatation. In addition, NO maintains the endothelium and medial smooth muscle cells in a non-proliferative state and, when released into the blood, NO inhibits platelets and leukocytes. An NO-independent pathway also contributes to vasodilator tone but has not yet been fully elucidated (33–35).

The actions of NO are opposed by endothelium-derived vasoconstrictor factors, such as endothelin and vasoactive prostanoids, and by angiotensin II, which is converted at the endothelial surface from angiotensin I. These mediators cause vasoconstriction, activate endothelial cells, platelets, and leukocytes, and facilitate thrombosis, directly countering the inhibitory effects of NO (33–35).

Endothelial activation and dysfunction

Exposure to cardiovascular risk factors (including tobacco use, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, and diabetes) activates mechanisms within endothelial cells that result in expression of chemokines, cytokines, and adhesion molecules programmed to interact with leukocytes and platelets. At a molecular level risk factor exposure appears to induce a switch from NO-mediated inhibition of endothelial and other cellular processes towards endothelial activation via redox signalling. As part of endothelial activation eNOS, which normally maintains the endothelium in a quiescent state via production of NO, switches to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS). This process is termed eNOS uncoupling, and results in superoxide production if there is tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency, and hydrogen peroxide production if levels of L-arginine are inadequate. The resulting oxidative stress within the endothelium leads to increased production of endothelin and other mediators, which promote endothelial activation (34, 35).

Collectively, these processes result in endothelial dysfunction, a systemic disorder affecting all arteries that predisposes to vasoconstriction, increased endothelial cell permeability, expression of adhesion molecules, increased chemokine secretion, leukocyte adherence and migration, vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, and platelet activation and thrombosis (35, 36) (Fig 1.4).

Clinical indicators of endothelial activation, such as endothelial vasomotor dysfunction, can predict cardiovascular events in patients with and without overt coronary artery disease (37) but correction of cardiovascular risk factors has been shown to improve endothelial function. For example, treatment of hypercholesterolaemia with statins has been shown to improve or normalize endothelial function in patients with mild coronary artery disease (38). Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE I) also improve endothelial function through a range of mechanisms (antioxidant effects, favourable effect on fibrinolysis, reduction in angiotensin II, increase in bradykinin), although a direct relationship between these effects and the risk of adverse cardiovascular events has not yet been clearly established (39).

Early stages of atherosclerosis

The mechanisms that underlie the initial stages of atherosclerosis have not been fully elucidated but endothelial activation appears to be integral to the process. Endothelial activation precedes the onset of the disease, facilitates inflammatory processes that lead to atherosclerosis, and promotes mechanisms of disease progression.

Figure 1.4 Simplified schematic of atherogenesis. Nitric oxide (NO) secreted by endothelial cells (EC) causes relaxation of smooth muscle cells (SMC) and vasodilatation. NO also inhibits (–) platelets and leukocytes. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) enters the subendothelial space and is modified, generating oxidized LDL (Ox-LDL). Endothelial activation and dysfunction causes generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and endothelin, expression of cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) on the endothelial cells, and activation of platelets and monocytes (+). Monocytes adhere to the endothelium and, under the influence of chemokines, migrate into the subendothelial space. Macrophage colony stimulating factor (MCSF) induces monocyte differentiation into macrophages. Activated macrophages phagocytose lipid and develop into foam cells.

Lipid retention and modification

In the earliest stage of atherosclerosis LDL particles probably enter the subendothelial space from the bloodstream. Apolipoprotein in the LDL particles is thought to bind to extracellular proteoglycans (especially biglycan) and other macromolecules, ensuring retention of lipid within the extracellular matrix (40, 41). LDL particles may be modified through oxidation and glycation. The precise pathways of this chemical transformation are uncertain but evidence implicates myeloperoxidase and 12/15-lipoxygenase, peroxidase enzymes found predominantly in neutrophils, monocytes, and some macrophages (42, 43).

Inflammation

Modified and oxidized LDLs contribute to endothelial activation and initiate an inflammatory response in the vessel wall. Activated endothelium expresses several types of cell adhesion molecules (CAMs), which facilitate adhesion of leukocytes rolling along the endoluminal surface of the vessel wall to the endothelium. Chemokines produced in the endothelial cells then stimulate migration of the adherent monocytes and T cell lymphocytes into the subendothelial space (44–46).

Macrophage colony stimulating factor, a cytokine produced in the activated endothelial cells, stimulates monocytes within the intima to differentiate into macrophages. Recruited macrophages express several different polarization phenotypes and have numerous effects on lesion development. The commonest phenotype is the M1 macrophage, which triggers a predominantly proinflammatory response (47). This M1 transformation is

associated with upregulation of scavenger receptors and Toll-like receptors on the macrophage cell surface that bind modified LDL and oxidized phospholipid. Activation of macrophage Toll-like receptors also induces intracellular signalling and cell activation, with cytoskeletal rearrangements, stimulation of inflammatory cytokine secretion, and production of proteases and cytotoxic oxygen radicals. These processes facilitate endocytosis and destruction of the oxidized LDL particles, but if the lipid cannot be fully metabolized it accumulates as cytosolic droplets and the macrophage transforms into a foam cell (44, 48). Other macrophages assume an M2 phenotype with predominantly anti-inflammatory effects. This balance between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory phenotypes is incompletely understood but will have a significant influence on disease progression (49).

Lymphocytes within the intima also produce inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, proteases, and cytotoxic oxygen and nitrogen radical molecules. Cytokines may induce expression of CD40, a transmembrane protein receptor present on inflammatory cells within the plaque. Activation of CD40 by CD40 ligand, derived from platelets and other cells, signals upregulation of proinflammatory and atherogenic genes (50). This process is known to involve the intracellular nuclear factor kappa B transcription pathway, which controls the transcription of genes for many cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, and regulators of apoptosis (51). These processes augment and perpetuate the inflammatory atherosclerotic process and recruit additional macrophages and medial smooth muscle cells. If the inflammatory response does not remove or neutralize the initiating stimulus it can continue unabated.

Endothelin Endothelial activation

The accumulation of lipid-laden monocytes, foam cells, and T cell lymphocytes within the intima leads to the formation of fatty streaks and early atherosclerotic lesions (Fig 1.5). Fatty streaks are prevalent in young people and are generally considered to be an antecedent of atheroma, but they may also disappear over time (52). Evidence of early atherosclerosis has been demonstrated in post-mortem studies of young soldiers killed during the Vietnam (53) and Korean (54) wars and in intracoronary ultrasound studies of transplanted hearts retrieved from teenage and young adult donors (55).

Disease progression

Plaque growth

As the atherosclerotic process progresses the plaque increases in size due to accumulation of inflammatory and smooth muscle cells, production of extracellular matrix, and continuing deposition of lipid in the arterial wall. Vascular smooth muscle cells, stimulated by mitogens and cytokines, differentiate into migratory and secretory cells and migrate into the intima (56) (Fig 1.6) Smooth muscle cells produce collagen and other matrix proteins, including glycosaminoglycans, proteoglycans, elastin, fibronectin, laminin, vitronectin, and thrombospondin (57).

Arterial remodelling

During growth of atherosclerotic plaque the entire vessel can vary in size, a process known as remodelling. Enlargement of the vessel may accommodate the plaque volume without compromising the arterial lumen until the plaque enlarges to over 40% of the vessel cross-sectional area, but thereafter further growth in the plaque causes luminal narrowing (57, 58). Alternatively, the vessel may constrict and further narrow the arterial lumen. Progressive luminal narrowing can obstruct coronary blood flow and lead to stable angina pectoris. The mechanisms regulating remodelling

have not been elucidated but may contribute to heterogeneity in the progression and clinical manifestations of arterial disease (59).

Plaque neovascularization

As atheromatous disease advances, new microvessels may develop from the adventitial vasa vasorum, possibly in response to hypoxia and activation of Toll-like receptors within the expanding atherosclerotic plaque. This process appears to be regulated by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) A, which, together with angiotensin II, can also induce microvascular permeability. These processes may facilitate extravasation of red blood cells and intraplaque haemorrhage. Release of haemoglobin into the extracellular matrix exacerbates oxidative stress, amplifying macrophage activation and proinflammatory signals, and accelerating the atherosclerotic process (60).

Apoptosis

Apoptosis of the cellular components of the plaque may be mediated by cytokines, including interleukin-1, tumour necrosis factoralpha, and interferon-gamma (61). Apoptosis has been observed at all stages of atherosclerosis but the consequences for lesion progression may depend on how efficiently the apoptotic cell is cleared by other macrophages. This phagocytic clearance (efferocytosis) appears to be efficient in early lesions, reducing lesion cellularity and atheroma progression. In more advanced lesions efferocytosis may be defective, leading to secondary necrosis of the apoptotic cell, further release of inflammatory mediators, and amplification of the inflammatory process (62). Cumulatively these events may lead to the development of a highly thrombogenic necrotic core within the expanding plaque, which contains cell remnants expressing active tissue factor (63). As the necrotic lipid-rich core expands, a fibrous cap forms over the luminal surface, creating a barrier between the thrombogenic material within the core and the circulating blood (Fig 1.6).

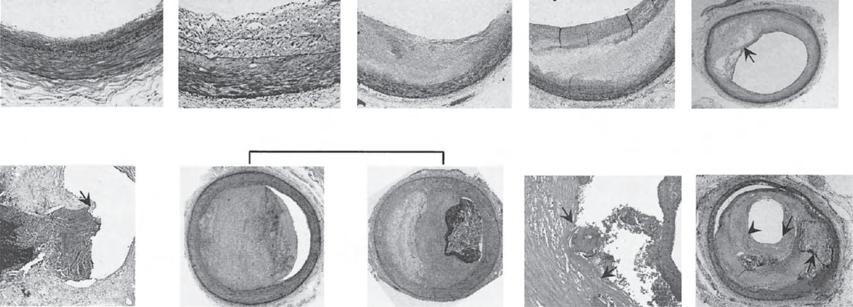

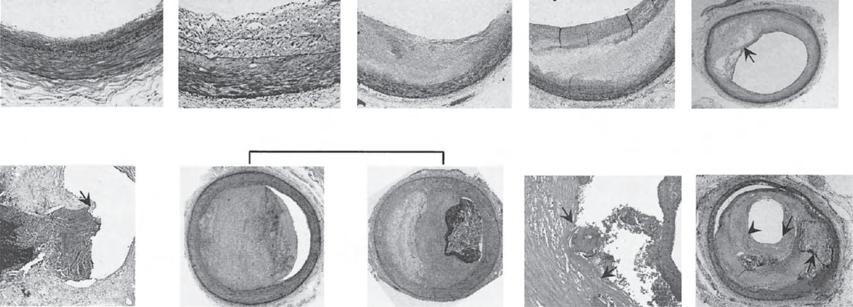

Histopathology of plaque progression. Descriptions begin at top, from left to right. Intimal thickening is normal in all age groups and is characterized by smooth muscle cell accumulation within the intima. Intimal xanthoma corresponds to the fatty streak and denotes the accumulation of macrophages and lymphocytes within the intimal thickening lesion. Pathological intimal thickening denotes the accumulation of extracellular lipid. Fibrous cap atheroma indicates the presence of a necrotic core under a fibrous cap, which may become thinned (thin-cap atheroma). This lesion may rupture, with exposure of the necrotic core to the lumen. The thrombus of a plaque erosion may overlie pathological intimal thickening (left) or fibrous cap atheroma (right). Calcified nodule is a rare cause of coronary thrombosis. Acute rupture may progress to healing (healed plaque rupture) without luminal occlusion. EL, Extracellular lipid; FC, fibrous cap; NC, necrotic core; Th, thrombus. Reproduced from Frostegard J, Ulfgren AK, Nyberg P, et al. Cytokine expression in advanced human atherosclerotic plaques: dominance of pro-inflammatory (Th1) and macrophage-stimulating cytokines. Atherosclerosis 1999; 145(1):33–43 with permission from Elsevier.

Figure 1.5

Apoptosis

Vulnerable plaque with thin fibrous cap Matrix degradation

SMC migration & differentiation

Figure 1.6 As oxidized lipid accumulates, monocytes are recruited to the developing plaque. Cytokines and mitogens stimulate recruitment and proliferation of smooth muscle cells (SMCs). SMCs produce extracellular matrix, which increases plaque volume. Apoptosis of endothelial cells and impaired endothelial regeneration may lead to plaque erosion. Apoptosis of cells within the plaque leads to the development of a lipid-rich necrotic core. The overlying fibrous cap may be degraded by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and other proteases, increasing the risk of plaque rupture. Other abbreviations as in Fig 1.4.

Endothelial cells can also progress to senescence and may detach into the circulation. Whole endothelial cells and microparticles derived from activated or apoptotic endothelial cells can be detected in the circulating blood as markers of endothelial injury and are thought to influence blood thrombogenicity (64). Restoration of endothelial integrity involves replication of adjacent mature endothelial cells or recruitment of circulating endothelial progenitor cells. Mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells is influenced by NO and may therefore be impaired in individuals with cardiovascular risk factors (35, 65). In animal models restoration of endothelial integrity after balloon injury is enhanced with exercise or statins, which both improve endothelial function (66, 67).

Influence of biomechanical forces

Dysfunctional endothelium, fatty streaks, and atheroma all localize preferentially to arterial sites associated with disturbed flow patterns, suggesting an important role for local haemodynamic forces in the development of arterial disease. These sites include branch points on the opposite side of the flow divider, and post-stenotic segments where disturbances in laminar flow result in recirculation eddies, flow separation, and oscillatory flows. Evidence suggests that exposure of the endothelium to such different biomechanical forces induces differential expression of specific genes in endothelial cells. Laminar shear stress from the viscous flow of blood against the endothelial cell surface induces eNOS activity, which supports vasoprotective functions in the endothelium. By contrast, reduced or oscillatory shear stress induces endothelial activation, expression of adhesion molecules, and endothelial cell apoptosis (68–73).

Calcification of atheroma

Microscopic areas of calcification may appear within the atherosclerotic plaque, which become denser as the disease advances. The extent of coronary calcification correlates closely with the severity of luminal narrowing caused by the plaque (74). The predominant chemical constituent of coronary calcification is identical to hydroxyapatite, the main inorganic constituent of bone (75). Osteopontin, a gylcosylated protein involved in the formation and calcification of bone, is synthesized by macrophages, smooth muscle, and endothelial cells. Endothelial progenitor cells in patients with coronary disease have also been shown to express osteocalcin, an osteoblastic marker (61, 76). The significance of calcification for plaque progression and cardiac events is uncertain, but extensive calcification may impact the outcome of percutaneous coronary intervention. Rarely, eruptive nodular calcification with underlying fibrocalcific plaque is implicated as a cause of coronary thrombosis (77) (Fig 1.5).

Plaque rupture, erosion, and thrombosis

Encroachment of atherosclerotic plaque into the lumen of a coronary artery without thrombosis can cause stable angina pectoris; however, acute coronary syndromes are caused by luminal thrombosis or sudden plaque haemorrhage into an atherosclerotic plaque with or without concomitant vasospasm. In ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) the thrombus is occlusive and sustained, whereas in unstable angina and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) the thrombus is typically non-occlusive and dynamic (78). Detailed histopathological examination of coronary arteries in sudden cardiac death victims has revealed two broad categories of plaque ‘events’ that lead to thrombosis, with

approximately 75% of fatal coronary thrombi due to plaque rupture and the remaining 25% due to plaque erosion (77).

Plaque rupture

Most atherosclerotic plaques develop slowly over many years, under the influence of local immune responses and continued exposure to cardiovascular risk factors. Integrity of the fibrous cap overlying the plaque core is maintained by balanced production and degradation of extracellular matrix proteins. If this balance is disturbed, overproduction of matrix may encroach on the arterial lumen, but increased matrix degradation may weaken the plaque cap, increasing the risk of plaque rupture.

Matrix protein degradation is mediated by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and other proteases released by inflammatory cells, including macrophages and migrated smooth muscle cells. MMPs are zinc2+-dependent endopeptidases and include collagenases, gelatinases, stromelysins, and metalloelastases. MMP activation is controlled at several levels, including induction of MMP gene transcription, post-translational activation of MMP proforms, and interaction with specific tissue inhibitors (TIMPs). MMPs may facilitate smooth muscle cell migration through the internal elastic lamina into the intima, are implicated in vascular remodelling, and appear to have a central role in plaque rupture. Expression of MMP activity is influenced by several drugs, including the HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) (57, 79).

Active degradation and remodelling of the extracellular plaque matrix by macrophages, via release of MMPs and other proteases and by subsequent phagocytosis, inhibits the formation of a stable fibrous cap. Further breakdown of collagen and other proteins within the fibrous cap reduces the structural integrity of the plaque and predisposes to plaque rupture (79, 80). Interaction between CD40 and CD40 ligand may induce MMP production and may play a role in plaque instability (50). Plaques with a thin fibrous cap, large lipid core, and inflammatory cell infiltrate at the thinnest portion of the cap appear to be particularly vulnerable to rupture (77) (Fig 1.7). Inflammatory cells are abundant in the shoulder regions of ruptured plaque and many show signs of activation and inflammatory cytokine production (81, 82). Histopathological specimens show rupture typically at this thin shoulder region of the collagenous fibrous cap, with discontinuity of the cap at the site of contact between thrombus and the lipid core. In one study 95% of ruptured plaques had a cap thickness of <65 μm and such plaques were termed thin-cap fibroatheromas (TCFAs) (83). This led to the concept of the vulnerable plaque, which might be a target for treatment to prevent plaque rupture and subsequent coronary thrombosis. This has, however, been challenged by the PROSPECT study, which used virtual histology intravascular ultrasound (VH-IVUS) and showed that only around 5% of TCFAs caused coronary events during a 3.4-year follow-up period (84).

Plaque erosion

In other cases coronary thrombosis occurs at the site of a superficial plaque erosion, without involvement of a lipid core. The luminal surface is irregular and devoid of endothelial cells, and the plaque in contact with the thrombus is generally cellular and rich in proteoglycan. Endothelial apoptosis with deficient endothelial repair may be the underlying cause of plaque erosion. Plaque erosion is particularly likely in young women, but with advancing age plaque rupture becomes the dominant cause of coronary thrombosis

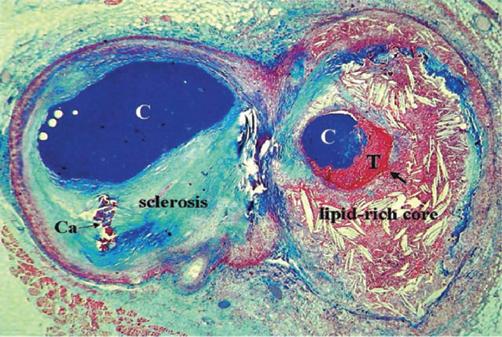

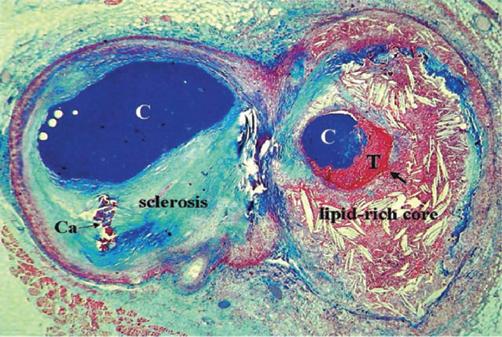

Figure 1.7 Atherothrombosis: a variable mix of chronic atherosclerosis and acute thrombosis. Cross-sectioned arterial bifurcation illustrating a collagen-rich (blue-stained) plaque in the circumflex branch (left) and a lipid-rich and ruptured plaque (arrow) with a non-occlusive thrombosis superimposed in the obtuse marginal branch (right). C, Contrast in the lumen; Ca, calcification; T, thrombosis. Reproduced from Falk E, Prediman S, Fuster V. Coronary plaque disruption. Circulation 1995; 92:657–71.

(77, 85) (Figs 1.4, 1.5, and 1.6). Over the past 10–15 years there has been a shift in the mode of presentation of acute coronary syndrome in the western world, with a decline in STEMI and a rise in NSTEMI (86). This is coincident with and may relate to a decline in cigarette smoking together with increased use of HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) to treat elevated LDL levels while other risk factors such as obesity, diabetes, high triglycerides, and low HDL levels are increasingly seen (87). Recent optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging studies have suggested that a growing proportion of acute coronary syndromes are caused by plaque erosion rather than plaque rupture and that erosion associates more frequently with NSTEMI than STEMI (88, 89).

Thrombosis

Rupture of a coronary artery plaque causes an acute change in plaque morphology, exposure of tissue factor, and other thrombogenic plaque contents to the circulating blood, activation of the coagulation cascade, and coronary thrombosis (Fig 1.8). Plaque erosion is probably a weaker thrombogenic stimulus and the drivers of thrombus formation in this situation are less well understood.

The magnitude of the thrombotic response on ruptured or eroded plaques is very variable and the development of a major luminal thrombus sufficient to trigger a clinical event is relatively rare. The consequences of plaque rupture and erosion are determined by the severity of the plaque injury, local rheology, and the balance between thrombotic and lytic activity at the interface between the plaque and the circulating blood. These factors influence the size and stability of the thrombus, and the severity of the resulting coronary syndrome. Partial or complete thrombotic occlusion of the artery, or thrombus embolism into the distal vessel, may cause myocardial ischaemia and an acute coronary syndrome. More frequently, however, it is thought that plaque rupture occurs silently, and subsequent repair of the vascular injury and fibrotic organization of the thrombus may cause accelerated plaque growth, contributing to progression of the atherothrombotic process (61).

Figure 1.8 Activated macrophages may cause progressive degradation of the fibrous cap over the lipid core. Plaque rupture exposes the thrombogenic core contents to the circulating blood. Tissue factor (TF) and other thrombogenic factors stimulate the coagulation cascade and cause luminal thrombosis. RBC, Red blood cell. Other abbreviations as in Figure 1.4.

Angiographic studies of patients before and after myocardial infarction suggest that the culprit stenosis responsible for the acute coronary syndrome is frequently only of moderate severity (90, 91). Mild or moderate coronary stenoses may be an important cause of acute coronary syndrome because they are much more prevalent than severe stenoses, which are individually at higher risk of causing coronary thrombosis (92).

Neoatherosclerosis

Percutaneous coronary intervention successfully treats obstructive coronary atheroma both in the setting of stable angina pectoris and acute coronary syndromes. Drug eluting stents have overcome the problem of neointimal overgrowth within bare metal stents leading to in-stent restenosis, but the delayed vascular healing caused by the potent antiproliferative drugs is associated with instent neoatherosclerosis and potential late stent failure due to stent thrombosis (93).

Systemic markers of inflammation

There is increasing evidence that atherosclerosis is associated with chronic low-grade inflammation in clinically silent plaques throughout the vascular system (44). Coronary arteriographic studies have demonstrated multiple complex plaques (characterized by thrombus, ulceration, plaque irregularity, and impaired flow) in nearly 40% of patients with recent myocardial infarction, supporting the concept that plaque instability is because of a systemic increase in inflammation (94). The blood levels of several markers of inflammation, including C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukins, soluble CD40 ligand, and tissue factor, are all elevated in patients with acute coronary syndromes, and high levels generally predict worse outcome (95, 96). Elevated levels of CRP, serum

amyloid A, interleukin-6, and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule type 1 are also all associated with cardiovascular risk in apparently healthy populations (97). CRP is an acute phase reactant and is mainly produced in the liver in response to interleukin-6. CRP has therefore been considered an inactive marker of inflammation, but there is some evidence that CRP may also play a direct role in atherogenesis (48, 95).

Drugs that reduce inflammation may have therapeutic effects in CHD. Aspirin use in otherwise healthy men reduced the risk of first myocardial infarction in those with the highest serum CRP levels (98). Long-term treatment with pravastatin reduces CRP levels and improves clinical outcome (99, 100). In another study, 17,802 healthy subjects with low LDL/cholesterol levels and elevated high-sensitivity CRP levels were randomized to treatment with rosuvastatin or placebo, but the trial was stopped prematurely because treatment with rosuvastatin reduced serum LDL and CRP levels and the incidence of major cardiovascular events (101). There are numerous ongoing trials of anti-inflammatory therapies in atherosclerotic disease, including inhibitors of the central proinflammatory cytokines IL-1, TNFα, and IL-6, antioxidants, adhesion molecule inhibitors, and vaccination using epitopes of oxidized LDL (102).

Limitations of the evidence base

Mechanistic evidence comes mainly from pathological specimens obtained from human autopsies and animal models where genetic manipulation leads to severe hypercholesterolaemia. Such models are limited in that they produce rapidly progressive asymptomatic plaques with infrequent thrombotic episodes as distinct from the chronic disease process seen over several decades in humans with clinical events commonly driven by plaque rupture or erosion

TF Necrotic core

with superimposed thrombus formation. Consequently there is much greater knowledge of how LDL causes atherosclerotic plaque formation than there is of the role of other important risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, high triglyceride, and low HDL levels. It is also not clear why some plaques, but not others, cause thrombotic complications and why these events can vary from a clinically silent self-healing episode to an occlusive luminal thrombosis causing an acute coronary syndrome. It seems likely that the balance of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory mechanisms within the plaque and the circulating blood play a key role in determining the outcome related to a given plaque (49). In recent years in vivo imaging techniques within coronary arteries such as VH-IVUS and OCT as well as positron emission tomography (PET) scanning looking at calcification and inflammation have provided additional mechanistic insights (103).

Summary

CHD remains a leading cause of death and disability across industrialized countries, is prevalent in Eastern Europe, and is a major threat to health in developing countries. Increases in the prevalence of coronary artery disease, both in the developed and developing countries, can be largely explained by coronary risk factors, including tobacco use, high blood lipid levels, hypertension, obesity, and diabetes.

Atherothrombosis, the pathological process underlying most cases of CHD, is defined as atherosclerosis with superimposed thrombosis. The molecular and cellular mechanisms of atherothrombosis are incompletely understood, but there is compelling evidence that the disease is due to a chronic inflammatory process in the arterial intima. Exposure to risk factors and deposition of lipoprotein in the intima cause upregulation of atherogenic and prothrombotic processes. Monocytes are recruited into the intima from the circulating blood and a series of inflammatory mechanisms lead to the development of an atherosclerotic plaque. Endothelial apoptosis and inadequate endothelial repair over the plaque may lead to endothelial erosion and arterial thrombosis. Development of a necrotic lipid core within the plaque and degradation of the overlying fibrous cap by proteases render the plaque vulnerable to disruption. Plaque rupture exposes the core contents to the circulating blood and potent thrombogenic stimuli activate the coagulation cascade, causing arterial thrombosis. In many cases coronary plaque erosion or rupture occur silently, but if the thrombosis impedes coronary blood flow the myocardium may become ischaemic, and the patient may present with an acute coronary syndrome, myocardial infarction, or death. The development of treatment strategies to combat these complex molecular, cellular, and physiological disturbances presents interventional cardiology with the greatest challenge.

References

1. GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and causespecific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;385:117–71.

2. Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006;3:e442.

3. Townsend N, Bhatnagar P, Wilkins E, Wickramasinghe K, Rayner M. Cardiovascular Disease Statistics. London: British Heart Foundation, 2015.

4. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014;129:e28–e292.

5. Allender S, Peto V, Scarborough P, Kaur A, Rayner M. Coronary Heart Disease Statistics. London: British Heart Foundation, 2008.

6. Ford ES, Capewell S. Coronary heart disease mortality among young adults in the U.S. from 1980 through 2002: concealed leveling of mortality rates. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:2128–32.

7. O’Flaherty M, Buchan I, Capewell S. Contributions of treatment and lifestyle to declining CVD mortality: why have CVD mortality rates declined so much since the 1960s? Heart 2013;99:159–62.

8. Unal B, Critchley JA, Capewell S. Explaining the decline in coronary heart disease mortality in England and Wales between 1981 and 2000. Circulation 2004;109:1101–107.

9. Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, Critchley JA, Labarthe DR, Kottke TE et al. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2388–98.

10. Tunstall-Pedoe H, Vanuzzo D, Hobbs M, Mahonen M, Cepaitis Z, Kuulasmaa K et al. Estimation of contribution of changes in coronary care to improving survival, event rates, and coronary heart disease mortality across the WHO MONICA Project populations. Lancet 2000;355:688–700.

11. Kottke TE, Faith DA, Jordan CO, Pronk NP, Thomas RJ, Capewell S. The comparative effectiveness of heart disease prevention and treatment strategies. Am J Prev Med 2009;36:82–8.

12. Gupta R, Joshi P, Mohan V, Reddy KS, Yusuf S. Epidemiology and causation of coronary heart disease and stroke in India. Heart 2008;94:16–26.

13. Moran AE, Forouzanfar MH, Roth GA, Mensah GA, Ezzati M, Murray CJL et al. Temporal trends in ischemic heart disease mortality in 21 world regions, 1980 to 2010: The Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Circulation 2014;129:1483–92.

14. Finegold JA, Asaria P, Francis DP. Mortality from ischaemic heart disease by country, region, and age: statistics from World Health Organization and United Nations. International Journal of Cardiology 2013;168:934–45.

15. Moran AE, Tzong KY, Forouzanfar MH, Rothy GA, Mensah GA, Ezzati M et al. Variations in ischemic heart disease burden by age, country, and income: the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors 2010 study. Glob Heart 2014;9:91–9.

16. Luepker RV, Apple FS, Christenson RH, Crow RS, Fortmann SP, Goff D et al. Case definitions for acute coronary heart disease in epidemiology and clinical research studies: a statement from the AHA Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; AHA Statistics Committee; World Heart Federation Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Epidemiology and Prevention; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation 2003;108:2543–9.

17. Braunwald E, Morrow DA. Unstable angina: is it time for a requiem? Circulation 2013;127:2452–7.

18. Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Flegal K et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 2009;119:e21–181.

19. MacIntyre K, Murphy NF, Chalmers J, Capewell S, Frame S, Finlayson A et al. Hospital burden of suspected acute coronary syndromes: recent trends. Heart 2006;92(5):691–2.

20. McManus DD, Gore J, Yarzebski J, Spencer F, Lessard D, Goldberg RJ. Recent trends in the incidence, treatment, and outcomes of patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. Am J Med 2011;124:40–7.

21. Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial

infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet 2004;364:937–52.

22. McGorrian C, Yusuf S, Islam S, Jung H, Rangarajan S, Avezum A et al. Estimating modifiable coronary heart disease risk in multiple regions of the world: the INTERHEART Modifiable Risk Score. Eur Heart J 2011;32:581–9.

23. Yusuf S, Rangarajan S, Teo K, Islam S, Li W, Liu L et al. Cardiovascular risk and events in 17 low-, middle-, and high-income countries. New Engl J Med 2014;371:818–27.

24. Teo KK, Ounpuu S, Hawken S, Pandey MR, Valentin V, Hunt D et al. Tobacco use and risk of myocardial infarction in 52 countries in the INTERHEART study: a case-control study. Lancet 2006;368:647–58.

25. Prospective SC, Lewington S, Whitlock G, Clarke R, Sherliker P, Emberson J et al. Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths. Lancet 2007;370:1829–39.

26. Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Buck G, Pollicino C et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet 2005;366:1267–78.

27. Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R, Prospective SC et al. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 2002;360:1903–13.

28. Ezzati M, Oza S, Danaei G, Murray CJ. Trends and cardiovascular mortality effects of state-level blood pressure and uncontrolled hypertension in the United States. Circulation 2008;117:905–14.

29. Prospective SC, Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, Clarke R, Emberson J et al. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet 2009;373:1083–96.

30. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. High body mass index for age among US children and adolescents, 2003–2006. JAMA 2008;299:2401–5.

31. Emberson J, Whincup P, Morris R, Walker M, Ebrahim S. Evaluating the impact of population and high-risk strategies for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J 2004;25:484–91.

32. Furchgott RF, Zawadzki JV, Furchgott RF, Zawadzki JV. The obligatory role of endothelial cells in the relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by acetylcholine. Nature 1980;288:373–6.

33. Verma S, Anderson TJ. Fundamentals of endothelial function for the clinical cardiologist. Circulation 2002;105:546–9.

34. Forstermann U, Munzel T. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase in vascular disease: from marvel to menace. Circulation 2006;113:1708–14.

35. Deanfield JE, Halcox JP, Rabelink TJ. Endothelial function and dysfunction: testing and clinical relevance. Circulation 2007;115:1285–95.

36. Hink U, Li H, Mollnau H, Oelze M, Matheis E, Hartmann M et al. Mechanisms underlying endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Circ Res 2001;88:E14–E22.

37. Halcox JP, Schenke WH, Zalos G, Mincemoyer R, Prasad A, Waclawiw MA et al. Prognostic value of coronary vascular endothelial dysfunction. Circulation 2002;106:653–8.

38. Suwaidi JA, Hamasaki S, Higano ST, Nishimura RA, Holmes DR, Jr., Lerman A. Long-term follow-up of patients with mild coronary artery disease and endothelial dysfunction. Circulation 2000;101:948–54.

39. Anderson TJ, Elstein E, Haber H, Charbonneau F. Comparative study of ACE-inhibition, angiotensin II antagonism, and calcium channel blockade on flow-mediated vasodilation in patients with coronary disease (BANFF study). J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:60–6.

40. Khalil MF, Wagner WD, Goldberg IJ. Molecular interactions leading to lipoprotein retention and the initiation of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2004;24:2211–18.

41. Nakashima Y, Wight TN, Sueishi K. Early atherosclerosis in humans: role of diffuse intimal thickening and extracellular matrix proteoglycans. Cardiovascular Research 2008;79:14–23.

42. Nicholls SJ, Hazen SL. Myeloperoxidase and cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005;25:1102–11.

43. Huo Y, Zhao L, Hyman MC, Shashkin P, Harry BL, Burcin T et al. Critical role of macrophage 12/15-lipoxygenase for atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice Circulation 2004;110:2024–31.

44. Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1685–95.

45. Gleissner CA, Leitinger N, Ley K. Effects of native and modified lowdensity lipoproteins on monocyte recruitment in atherosclerosis. Hypertension 2007;50:276–83.

46. Leitinger N. Oxidized phospholipids as modulators of inflammation in atherosclerosis. Current Opinion in Lipidology 2003;14:421–30.

47. Leitinger N, Schulman IG. Phenotypic polarization of macrophages in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2013;33:1120–6.

48. Miller YI, Chang MK, Binder CJ, Shaw PX, Witztum JL. Oxidized low density lipoprotein and innate immune receptors. Current Opinion in Lipidology 2003;14:437–45.

49. Libby P, Tabas I, Fredman G, Fisher EA. Inflammation and its resolution as determinants of acute coronary syndromes. Circulation Research 2014;114:1867–79.

50. Antoniades C, Bakogiannis C, Tousoulis D, Antonopoulos AS, Stefanadis C. The CD40/CD40 ligand system: linking inflammation with atherothrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:669–77.

51. de Winther MPJ, Kanters E, Kraal G, Hofker MH. Nuclear factor {kappa}B signaling in atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005;25:904–14.

52. Stary HC. Evolution and progression of atherosclerotic lesions in coronary arteries of children and young adults. Arteriosclerosis 1989;9 (suppl):I19–I32.

53. McNamara JJ, Molot MA, Stremple JF, Cutting RT. Coronary artery disease in combat casualties in Vietnam. JAMA 1971;216:1185–7.

54. Virmani R, Robinowitz M, Geer JC, Breslin PP, Beyer JC, McAllister HA. Coronary artery atherosclerosis revisited in Korean war combat casualties. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1987;111:972–6.

55. Tuzcu EM, Hobbs RE, Rincon G, Bott-Silverman C, De Franco AC, Robinson K et al. Occult and frequent transmission of atherosclerotic coronary disease with cardiac transplantation. Insights from intravascular ultrasound. Circulation 1995;91:1706–13.

56. Hedin U, Roy J, Tran PK. Control of smooth muscle cell proliferation in vascular disease. Current Opinion in Lipidology 2004;15:559–65.

57. Faxon DP, Fuster V, Libby P, Beckman JA, Hiatt WR, Thompson RW et al. Atherosclerotic vascular disease conference: writing group III: pathophysiology. Circulation 2004;109:2617–25.

58. Glagov S, Weisenberg E, Zarins CK, Stankunavicius R, Kolettis GJ. Compensatory enlargement of human atherosclerotic coronary arteries. N Engl J Med 1987;316:1371–5.

59. Pasterkamp G, de Kleijn DPV, Borst C. Arterial remodeling in atherosclerosis, restenosis and after alteration of blood flow: potential mechanisms and clinical implications. Cardiovascular Research 2000;45:843–52.

60. Moreno PR, Purushothaman KR, Sirol M, Levy AP, Fuster V, Moreno PR et al. Neovascularization in human atherosclerosis. Circulation 2006;113:2245–52.

61. Fuster V, Moreno PR, Fayad ZA, Corti R, Badimon JJ. Atherothrombosis and high-risk plaque: part I: evolving concepts. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:937–54.

62. Schrijvers DM, De Meyer GRY, Kockx MM, Herman AG, Martinet W. Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages is impaired in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005;25:1256–61.

63. Tabas I. Consequences and therapeutic implications of macrophage apoptosis in atherosclerosis: the importance of lesion stage and phagocytic efficiency. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005;25:2255–64.

64. Mutin M, Canavy I, Blann A, Bory M, Sampol J, Gnat-George F et al. Direct evidence of endothelial injury in acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina by demonstration of circulating endothelial cells. Blood 1999;93:2951–8.

65. Mallat Z, Tedgui A. Current perspective on the role of apoptosis in atherothrombotic disease. Circulation Research 2001;88:998–1003.

66. Walter DH, Rittig K, Bahlmann FH, Kirchmair R, Silver M, Murayama T et al. Statin therapy accelerates reendothelialization: a novel effect involving mobilization and incorporation of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells. Circulation 2002;105:3017–24.

67. Laufs U, Werner N, Link A, Endres M, Wassmann S, Jurgens K et al. Physical training increases endothelial progenitor cells, inhibits neointima formation, and enhances angiogenesis. Circulation 2004;109:220–6.

68. Chappell DC, Varner SE, Nerem RM, Medford RM, Alexander RW. Oscillatory shear stress stimulates adhesion molecule expression in cultured human endothelium. Circulation Research 1998;82:532–9.

69. Kinlay S, Libby P, Ganz P. Endothelial function and coronary artery disease. Current Opinion in Lipidology 2001;12:383–9.

70. Tricot O, Mallat Z, Heymes C, Belmin J, Leseche G, Tedgui A. Relation between endothelial cell apoptosis and blood flow direction in human atherosclerotic plaques. Circulation 2000;101:2450–3.

71. Gimbrone MA Jr, Cybulsky MI, Kume N, Collins T, Resnick N. Vascular endothelium. An integrator of pathophysiological stimuli in atherogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1995;748:122–31.

72. Dai G, Kaazempur-Mofrad MR, Natarajan S, Zhang Y, Vaughn S, Blackman BR et al. Distinct endothelial phenotypes evoked by arterial waveforms derived from atherosclerosis-susceptible andresistant regions of human vasculature. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:14871–6.

73. Wentzel JJ, Chatzizisis YS, Gijsen FJH, Giannoglou GD, Feldman CL, Stone PH. Endothelial shear stress in the evolution of coronary atherosclerotic plaque and vascular remodelling: current understanding and remaining questions. Cardiovasc Res 2012;96:234–43.

74. Burke AP, Virmani R, Galis Z, Haudenschild CC, Muller JE. Task force #2—what is the pathologic basis for new atherosclerosis imaging techniques? J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:1874–86.

75. Fitzpatrick LA, Severson A, Edwards WD, Ingram RT. Diffuse calcification in human coronary arteries. Association of osteopontin with atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest 1994;94:1597–604.

76. Gossl M, Modder UI, Atkinson EJ, Lerman A, Khosla S. Osteocalcin expression by circulating endothelial progenitor cells in patients with coronary atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:1314–25.