Opera in the Tropics

Music and eater in Early Modern Brazil

Rogério Budasz

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on le at the Library of Congress

ISBN 978–0–19–021582–8

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America is volume is published with the generous support of the Lloyd Hibberd Endowment of the American Musicological Society, funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

To Beatriz

CONTENTS

List of Figures ix

List of Tables xiii

List of Musical Examples xv

Acknowledgments xvii

About the Companion Website xxi

Introduction 1

1. Foundations 7

2. e Craft of Portuguese Opera 63

3. Musical Sources and Archives 112

4. Venues 157

5. People 224

6. Uses 297

Epilogue 357

Appendix 1: Abbreviations, Spelling, Pitch System, Currency, Conversion Rates, Cost of Living, Glossary 361

Appendix 2: Numbers in Demofonte 371

Appendix 3: Chronology, 1565–1807 379

Appendix 4: Chronology, 1808–1822 401

Bibliography 419

Index 443

FIGURES

1.1. Portuguese villages and indigenous aldeias mentioned in chapter 1. 9

1.2. Front page of Salvador de Mesquita, Sacri cium Iephte. 34

1.3. Salvador de Mesquita’s libretti for the Arciconfraternita del Santissimo Croci sso in San Marcello. 35

2.1. Comédia o mais heroico segredo ou Artaxerxe (detail). 80

2.2. Comédia o mais heroico segredo ou Artaxerxe (last page). 86

2.3. Bernardo José de Sousa Queirós, Cantoria 4, from Segunda parte da marujada. 96

3.1. Fragment of Jommelli’s aria “Figlia, qualor ti miro,” from L’I genia 119

3.2. A vocal bass excerpt from Inácio Parreiras Neves’s Oratória. 120

3.3. Title page of the bass part of Zara. 124

3.4. Bass part excerpt of aria “Já combatem dentro do peito,” assigned to Sra. Paula, in Zara 125

3.5. Francisco Curt Lange being interviewed in Rio de Janeiro. 126

3.6. Detail of gure 3.5, digitally enhanced, showing the voice and instrumental bass parts of the recitative “Falso Eneas.” 127

3.7. Voice and violin 1 parts of the recitative “Falso Eneas.” 127

3.8. Detail of violin part of Jommelli’s aria “Figlia, qualor ti miro,” used in a pasticcio setting of Demofoonte, assigned to Sr. Pedro. 139

3.9. Detail of violin 1 part of De Majo’s aria “Ah torto spergiuro,” used in a pasticcio setting of Demofoonte, assigned to Sra. Joaquina. 139

4.1. Cities and villages mentioned in table 4.1. 162

( x ) Figures

4.2. Fête religieuse portugaise à l’église de Saint-Gonzalès d’Amarante, engraving by Le Roux Durant. 163

4.3. Atas da Câmara de Salvador. 166

4.4. Salvador, Bahia, 2018. (1) Location of 1717, 1729, and 1760 tablados. (2) Location of 1729–1733 tablado/pátio de comédias (3) Teatro do Saldanha (tentative location). (4) Teatro do Guadalupe. (5) Teatro São João. 168

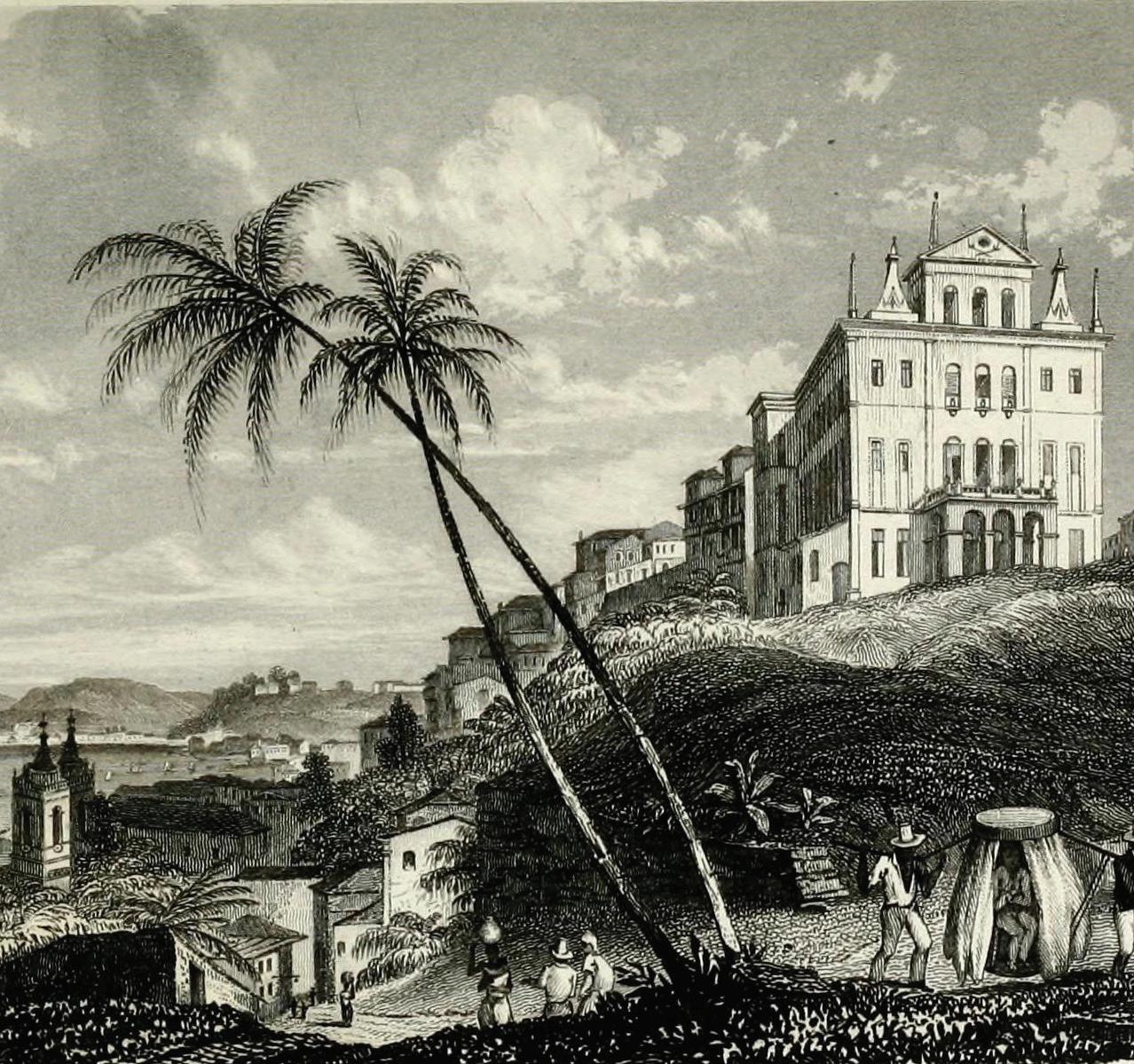

4.5. Grand théâtre a Bahia, engraving by Bachelier. 169

4.6. Rio’s casa da ópera in maps of (a) c 1760 (Opera) and (b) 1812 (letter h). 174

4.7. Depictions of Rio’s casa da ópera (at the left side of the viceroy’s palace): (a) Richard Bate, Palace Square, Rio de Janeiro, 1808, watercolor, c 1840; (b) Jean-Baptiste Debret, Vue de la Place du Palais à Rio de Janeiro, lithograph by ierry Frères; (c) JeanBaptiste Debret, Dèpart de la Reine, lithograph by ierry Frères; (d) Palais Imperial a Rio de Janeiro, lithograph by Louis Aubrun. 180

4.8. Jean-Baptiste Debret, “Acceptation provisoire de la constitution de Lisbonne, à Rio de Janeiro, en 1821.” 182

4.9. Ouro Preto, 2018. (1) Tentative location of Vila Rica’s old casa da ópera (c 1746–1751). (2) João de Sousa Lisboa’s casa da ópera (1769–). 184

4.10. São Paulo, 1810. (1) Tentative location of the old casa da ópera (1763–1766). (2) Governor Mourão’s casa da ópera (1767–1775). (3) Casa da ópera (1790–1820). 189

4.11. From 1767 to 1775, the theater operated in a hall inside the palace (left side); after 1790, another theater occupied the rightmost building. omas Ender, Koenigliche Residenz zu S. Paul, watercolor, 1818. 190

4.12. Paul Marcoy, “Vue du Cabildo,” 1869. 197

4.13. Location of the governor’s casa da ópera, 1791. Teodósio Constantino de Chermont, Plano geral da cidade do Pará em 1791. BN, Cartogra a (detail). 197

4.14. Ruine des eater, in Pará, November 30, 1842. 198

4.15. Front page of Antonio José de Paula, Drama intitulado Fidelidade, 1790. 200

4.16. (1) Parish church of Santo Antonio. (2) Senate/prison. (3) eater. 201

4.17. Cidade de Goiás, 2018. Tentative location of Vila Boa’s casa da ópera. 203

4.18. (1) Parish church, palace, and senate/prison. (2) Casa da ópera. 204

4.19. “Vue de Matto Grosso” (after a drawing by M. Weddell). François de Castelneau, Vues et Scénes Recueilles Pendant l’Expédition dans les Parties Centrales de l’Amérique du Sud, de Rio de Janeiro a Lima, et de Lima au Para (Paris: Bertrand, 1853). 205

4.20. Former location of the Pelourinho Square in Vila Bela, with the theater (M), pelourinho (I), and senate/prison (F). Top: “Planta da Vila Bella,” Arquivo da Casa da Ínsua (detail). Middle and bottom: the same area in 2015. 206

5.1. Gentleman (probably Antonio José de Paula) holding a copy of Segunda parte de Frederico II Rei da Prússia. 242

5.2. Michele Vaccani, around 1839. 248

5.3. Mariano Pablo Rosquellas. 250

5.4. “Orosmane parle et gesticule.” 272

5.5. Jean-Baptiste Debret, “Estudo de indumentária para teatro,” c 1818–1825. 274

5.6. Jean-Baptiste Debret, “Décor du théâtre de Rio de Janeiro,” c 1816–1820. 274

5.7. Jean-Baptiste Debret, “Décoration du ballet historique donné au éatre de la Cour, à Rio de Janeiro, le 13 Mai 1818,” lithograph by ierry Frères, 1834. 276

6.1. João Cardini, Victoria alcancada pelas armas britanicas, e potuguezas no sitio do Vimeiro contra os francezes em 21 de agosto de 1808. 323

6.2. Alessandro nell’Indie. Stage design for the concluding licenza. 338

TABLES

1.1. Anchieta’s contrafacta of “El sin ventura mancebo.” 16

1.2. Musical references in José de Anchieta’s plays. 21

1.3. Oratorio texts by Salvador de Mesquita. 33

1.4. Basic structure of a comedia function in late- seventeenth- century Spain. 41

1.5. Some features of selected Spanish dramatic genres (c 1690). 45

2.1. Eighteenth- century performances of works from eatro comico portuguez and Operas portuguezas. 69

2.2. Selected theatrical functions at the casa da ópera of São Paulo, 1769–1770. 84

2.3. Selected theatrical functions at an open-air theater in Cuiabá, 1790. 84

2.4. Selected functions at the Real Teatro de São João, 1817–1822. 91

2.5. Structural plan of Entremez da marujada and Segunda parte da marujada, by Bernardo José de Sousa Queirós. 99

3.1. Secular vocal music from the archive of Florêncio José Ferreira Coutinho. 117

3.2. Contents of the Bettencourt-Lange codices. 129

3.3. Lange’s additional manuscripts of theatrical music. 131

3.4. Music written in Brazil for dramas, elogios, and dramatic cantatas, 1808–1822. 134

3.5. Probable sequence of numbers in two performances of a pasticcio setting of Demofoonte, Rio de Janeiro, c 1790. 137

3.6. Provisional list (as of 2017) of pre-1843 theatrical music in Brazilian archives (excludes overtures, symphonies, and elogios). 141

4.1. eaters in Portuguese America (excludes simple platforms and tablados without boxes and backdrops). 160

5.1. Annual salaries of theatrical workers, eatro São João da Bahia, 1813. 225

5.2. Salaries of theatrical workers, Casa da Ópera de Vila Rica, January and February 1820. 227

5.3. Salaries of theatrical workers, eatro São Pedro de Alcantara, June 22– July 31, 1830. 229

6.1. Structural plan of O juramento dos numes 326

MUSICAL EXAMPLES

2.1. Arias from Guerras do alecrim e mangerona, Pirenópolis, c 1846. 71

2.2. Antonio Vieira dos Santos, “Marcha dos encantos de Medéia,” Cifras de música para saltério, c 1823. 73

2.3. José Maurício Nunes Garcia, “Coro em 1808 para o Benefício de Joaquina Lapinha . . . para o Entremez de Manoel Mendes.” 95

2.4. Bernardo José de Sousa Queirós, Cantoria 3, from Entremez da marujada. 96

2.5. Bernardo José de Sousa Queirós, Cantoria 4, “Lundum,” from Segunda parte da marujada 97

2.6. Bernardo José de Sousa Queirós, Cantoria 4, “Aria de negro,” from Entremez da marujada. 98

3.1. Inácio Parreiras Neves, excerpt of “Chegai a Deus Menino,” from Oratória 122

3.2. Galant schemata in Inácio Parreiras Neves’s Oratória 123

3.3. Bernardo José de Sousa Queirós, excerpt from “Coro de Turcos,” Zaira, Act 1, Scene 5. 147

3.4. Bernardo José de Sousa Queirós, Fatima’s aria, Zaira, Act 2, Scene 5. 147

6.1. Harmonic plan and programmatic aspects of recitative “Heroe, egregio.” 316

6.2. Bernardo José de Sousa Queirós, O juramento dos numes, Scene 2, Brontes’s aria. 336

6.3. Bernardo José de Sousa Queirós, O juramento dos numes, Scene 2, chorus of Cyclopes. 337

6.4. Pucitta, “Viva Enrico,” from La caccia di Enrico IV, Act 2, Scene 5. 344

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

is book is a natural consequence of a number of texts that I published from 2006 to 2010, mostly in Portuguese. During the past six years, further research in Portuguese and Brazilian archives allowed me to reevaluate, revise, and expand many ideas contained in those publications, taking care of a number of voids and loose ends and including previously unaddressed topics. Given its scope, this book exists in dialogue with the work of past and current scholars, which I am compelled to summarize in the following paragraphs. e reader may refer to the bibliography for additional information on these texts. Francisco Curt Lange inaugurated a new type of study of theater and music in Brazil with his 1964 article on opera and opera houses in Minas Gerais. He resorted to extensive archival research and for the rst time discussed a number of musical sources associated with the dramatic repertory of Portuguese America. Without the same reliance on musical sources, his study was closely followed by texts by Ayres de Andrade’s on Rio de Janeiro, Manuel Rodrigues Lapa and Afonso Ávila on Minas Gerais, and Carlos Francisco de Moura on Mato Grosso and Goiás. After a long hiatus, research in the area experienced a surge in the early 2000s with the biannual Encontros de Musicologia Histórica, coordinated by Paulo Castagna and sponsored by the Fundação ProMúsica of Juiz de Fora as part of its International Festival of Colonial Music. In 2002, I submitted a proposal for the complete staging of the opera Zaira at the festival. My role was to prepare an edition of the full score of this opera, composed in Rio de Janeiro by Bernardo José de Sousa Queirós around 1809, complemented with a paper that I read that year and later developed into an article. In July 2004, Kalinka Damiani, Marcos Liesenberg, Maécio Gomes, Murilo Neves, Tatiana Figueiredo, and Je erson Pires delivered a wholehearted performance of Zaira under the musical direction of Sérgio Dias, the stage direction of Walter Neiva, and the vocal direction of the great soprano Neyde omas, who sadly passed away in 2011.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the pioneering work of Manuel Carlos de Brito on opera in eighteenth- century Portugal, the methodic research that David Cranmer has been carrying out for many years at the Vila Viçosa archive, and Rui Vieira Nery’s critical investigation of music and theater in São

( xviii ) Acknowledgments

Paulo around 1770 have clari ed the outline of a shared Luso-Brazilian operatic culture. In 2008, a conference held at the Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian in Lisbon, coordinated by Rui Vieira Nery and Maria Elizabeth Lucas, brought together scholars who were working on a variety of aspects related to music in Portugal and Brazil during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. On the subject of music and theater, in addition to papers by Cranmer, Nery, and myself, Lucas Robatto unveiled documents on the construction and management of the Teatro São João of Salvador, Pablo Sotuyo Blanco revealed new data on opera composer Damião Barbosa de Araújo, and Márcio Páscoa addressed eighteenth- century operatic stagings in Amazonia. Since then, Rosana Marreco Brescia has been making important contributions to the eld. Her 2010 dissertation and her 2012 book explore the issue of theatrical architecture in innovative ways, while unveiling a number of primary sources on artists, managers, and other theatrical workers at Vila Rica’s casa da ópera. Lino de Almeida Cardoso also published a book rewriting the history of Rio’s theaters from 1775 to 1843. Inspired by Lucien Febvre’s historie totale approach, his research emphasizes socioeconomic and political analyses and is notable for its dense narrative and extensive archival support.

In such a dynamic context, any pretension of delivering a de nitive text may quickly turn into smoke. e eld is being shaped at this very moment by a network of scholars exploring complementary aspects of a shared LusoBrazilian historical continuum. On the other hand, if a recent surge in the development of technologies of information has positive impact on the way we carry out our investigations, we still rely immensely on in situ archival research and on direct interaction with people who dedicate their lives to the preservation and management of historical documents. I was fortunate to meet a number of extremely helpful professionals in the libraries and archives I visited during the past ten years. I am particularly thankful to Dolores Brandão and Maria Luísa Nery de Queiroz, at the Biblioteca Alberto Nepomuceno of the School of Music of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, for facilitating access to Sousa Queirós’s works and allowing me to browse a number of uncataloged works. I thank the sta at the Arquivo Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, for helping me navigate the tight schedule of this institution, and particularly Cláudio Braga for pointing me in the direction of some real treasures. I thank the sta at the Biblioteca Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, who during the past ten years handled my numerous requests in the departments of manuscripts, rare works, and iconography. I am deeply indebted to Suzana Martins and Adeilton Barral for facilitating my access to a number of sources at the music division, and to Eliane Perez, who coordinated my visiting scholarship at that institution. I also thank André Guerra Cotta, Júnia Ramos, Carla Alves, Glaura Lucas, Ana Cláudia de Assis, Edite Rocha, and Larissa Vitória, who at di erent times worked at the Acervo Curt Lange in Belo Horizonte, Vítor Gomes, and

the sta at the Museu da Música de Mariana, Mary Angela Biason and Suely Maria Perucci Esteves at the Museu da Incon dência and Casa do Pilar, Ouro Preto, and Abel Rodrigues at the Casa de Mateus, Vila Real. I warmly acknowledge the continuous help of João Ruas at the Paço Ducal de Vila Viçosa, since my rst visit to that beautiful institution in 1996, and also thank the current director of the Museu-Biblioteca Casa de Bragança, Maria de Jesus Monge. At the University of California, Riverside, I thank the head of our interlibrary loan division, Janet Moores, and the former head of our music library, Caitlin St. John.

I state without hesitation that the single factor that unchained the succession of events leading to this book was the Metastasio seminar I took with Bruce Alan Brown at the University of Southern California in 1998. Without his mentoring and his contagious passion for eighteenth-century opera, I doubt I would have ventured into this eld. I also thank my colleague and friend Walter Clark for nudging me into this speci c undertaking and for his inexhaustible enthusiasm. I thank Marita McClymonds for her continuous encouragement, John Rice for a number of key observations, Daniel Zuluaga for sharing his sources, David Irving for our enthusiastic conversations, Paulo Castagna for his prompt answerstomyinquiries andaccesstohis archive, David Cranmer for precious clues and many discussions, Rosana Marreco Brescia for our numerous conversations and exchanges, Marcelo Campos Hazan for carefully reviewing my previous book, Agostino Ziino for his encouragement, and Rodolfo Ilari for helping me with the Italian, French, and Latin translations. For inviting me to conferences and other events where I received useful feedback, I thank Ricardo Bernardes, Olivia Bloechl, Rosana Marreco Brescia, Marco Aurélio Brescia, Harry Lamott Crowl, Norton Dudeque, Manuel Pedro Ferreira, Maria Elizabeth Lucas, Pedro Luengo, Rui Vieira Nery, Sonia Ray, Hermínio de Sousa Santos (in memoriam) and his family, Nicolas Shumway, Louise Stein, Alejandro Vera, Maria Alice Volpe, Benjamin Walton, and Molly Warsh. For their help and suggestions on diverse issues, I thank Erith Ja eBerg, Pablo Sotuyo Blanco, Sérgio Dias, Marcos Holler, Liese Lange, Lucas Robatto, and Linda Tomko. For their patience and careful work, I thank the Oxford University Press sta and the anonymous reviewers of my proposal and nal manuscript. My warmest thanks go to my mother for her love and lifelong support and to my wife, daughter, and son for their love and patience during the many days I was away doing research and during the many hours I divided my attention between them and this laptop.

ABOUT THE COMPANION WEBSITE

Oxford University Press has created a website to accompany Opera in the Tropics: Music and eater in Early Modern Brazil. Musical scores of works discussed in the book may be downloaded through this site: www.oup.com/us/operainthetropics

Introduction

The year was 1548, and Dom João III, King of Portugal, was not very happy with the mediocre revenues from his settlements in the New World. It had been more than a decade since he had donated to his most trusted and wealthy subjects the chunk of land that the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas has secured to Portugal. While he expected his dalgos to protect the land and make it profitable, most of them ignored the call, allowing the French to set foot on his presumed possessions and to secure strong alliances with indigenous peoples, who, by the way, were not signatories of the Treaty of Tordesillas. Dom João’s territorial claims were now in jeopardy, and it was clear that his colonizing approach had failed miserably. After contemplating the alternatives, he changed his strategy by placing the entire territory under the tougher administration of a single governor, the decorated military o cer Tomé de Sousa. Notably, the document that contained Sousa’s appointment also established a new geopolitical entity: it was the rst o cial use of the name Terras do Brasil 1 In the following centuries, the colonial administration would switch from a centralized government to two more or less autonomous states and nally back to a centralized administration under a viceroy, but the terms Brasil and its plural form Brasis (Brazils) continued to be used since then to refer to Portuguese America as a whole.2

By the end of the eighteenth century, the Portuguese possessions in South America had almost tripled, far overstepping the limits established by the Treaty of Tordesillas.3 In many ways, the Portuguese administration built upon existing networks that indigenous nations had created, most remarkably the Tupi-Guarani, who inhabited more than eight thousand kilometers of coastal areas, spoke fairly similar languages and had for centuries enjoyed some level of cultural homogeneity. Learning what they knew about the environment and adopting their survival tactics were key factors for the success

of European missionaries and colonists,4 but that selective adoption of the local culture did not bene t the Tupi-Guarani. On the contrary, the colonial pact established a new economic order that resulted in tragic consequences for the indigenous peoples, while allowing a small number of Portuguese and Brazil-born landowners and gold contractors to become extremely wealthy. Not so fortunate were the lower- class Portuguese settlers and their Brazilborn descendants, mixed-race or not— who still had better chances for social mobility in the colony than in Portugal—along with a large number of slaves trying to make the best out of a really bad situation. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the unreliable nancial system, corrupt state bureaucracy, and the increasingly repressive administration fueled a number of uprisings of both colonists and slaves. ese revolts supplied material for regional foundation narratives but failed to provide a discourse that appealed simultaneously to inhabitants of di erent regions of the colony.

When a somewhat uni ed desire for emancipation nally surfaced in the early 1820s, it did not unfold in a full- edged revolution, did not involve the rejection of the Portuguese royal house, and did not dismiss Portugal as a model of civilization. Although around two thousand people died in the “Independence War,” its most perplexing result was keeping in power the very dynasty from which the colony wanted to break free.5

Other circumstances also played a role in the crafting of a distinct LusoBrazilian identity in the colony. e environment and its resources, the notion of space and time within a continental territory, the bureaucratic and often truculent exercise of authority and the type of resistance it provoked, the need to improvise and to adapt, the widespread use of slave labor, and the ethnic and cultural implications of the forceful relocation of large contingents of Central and West Africans were factors that in uenced life in the colony and helped in shaping the mindset, material culture, and arts of those living in the urban centers and extractivist settlements of the Terras do Brasil (hereafter Brazil)— whether they were of European, African, or indigenous ancestry. is book deals with some aspects of these dynamics. It explores the artistic needs and deeds of Brazilians during preindependence times, particularly those related to theater and music, expressed by the creative minds and bodies of actors, singers, poets, and composers who practiced musico-dramatic arts in the outskirts of the Western world. From the perspective of theatrical producers and sponsors, the following pages show how the threefold goal of instructing, entertaining, and distracting the population—as producer Fernando José de Almeida spelled out in 1825—had been present in diverse combinations since the early colonial period, at the hands of missionaries, intellectuals, bureaucrats, political leaders, and cultural producers.

From the morality plays that the Jesuits introduced in Bahia and São Paulo in the 1560s to the Italian operas staged in Rio de Janeiro to celebrate the new

independent nation in 1822, theatrical representations in Portuguese America featured music in a variety of forms and degrees. ese plays ranged from quintessentially Portuguese autos to comédias, entremezes, and oratórias, along with works identi ed as tragédias, dramas, and elogios dramáticos, among other designations. Opera is a particularly problematic concept in the Brazilian colonial context. Up to the late eighteenth century, a Brazilian who had never traveled abroad would associate the term opera primarily with the so- called óperas ao gosto português, or “operas in the Portuguese taste,” with spoken dialogues, quasi- stock characters, and a few musical numbers. Like its analogous vernacular traditions—Italian commedia, French comèdie, and Spanish comedia the Portuguese comédias and óperas (often used as synonyms) also developed a particular, local character, national but not nationalistic, which, in turn, experienced further modi cations in the colonial environment.

e circulation of scores, texts, and artists between Portugal and Brazil provides evidence of a shared theatrical culture. Being a tradition that relied on the written word and was sponsored by the upper economical and intellectual circles of a society— whose worldviews it re ected— theater was constrained by a set of conventions. Yet performances were not always identical. On paper, the colony was united under one king, one language, and one religion, but local factors determined di erences in terms of casting, vocal qualities, aesthetic paradigms, sense of humor, linguistic usage, and even interactions with indigenous and African culture and languages.

Political, social, and cultural factors in uenced and shaped the development of musico-dramatic arts in Portuguese America, at times re ecting, at times subverting existing conventions. e discovery and exploration of gold in the early 1700s had immediate consequences in the accelerated urbanization of the colony and the ourishing of new patterns of sociability, which, in turn, made possible the emergence of a commercial theatrical culture. Urbanization and economic development also determined an increasing diversity of the means of production, facilitating the negotiation of racial and gender prerogatives and providing opportunities for a newly assertive economic elite with aspirations of nobility. Under this scenario, theaters provided aesthetic pleasure, social visibility, economic and cultural capital, and opportunities for interaction among social actors from di erent walks of life. Overseeing these developments, administrative policies on issues ranging from urban design to social engineering also had a direct impact on theatrical arts in the colony, often departing from metropolitan models.

Chapter 1 of this book gives an overview of the main forms and conventions of theater with music from the mid-sixteenth to the early eighteenth century, as they surface in written sources and theatrical practices primarily related to Brazilian contexts. It considers the main theatrical genres, character types, and standard plots and the basic structure of theatrical functions, as well as the