https://ebookmass.com/product/once-we-were-slaves-laura-

https://ebookmass.com/product/once-we-were-slaves-laura-

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Leibman, Laura Arnold, author.

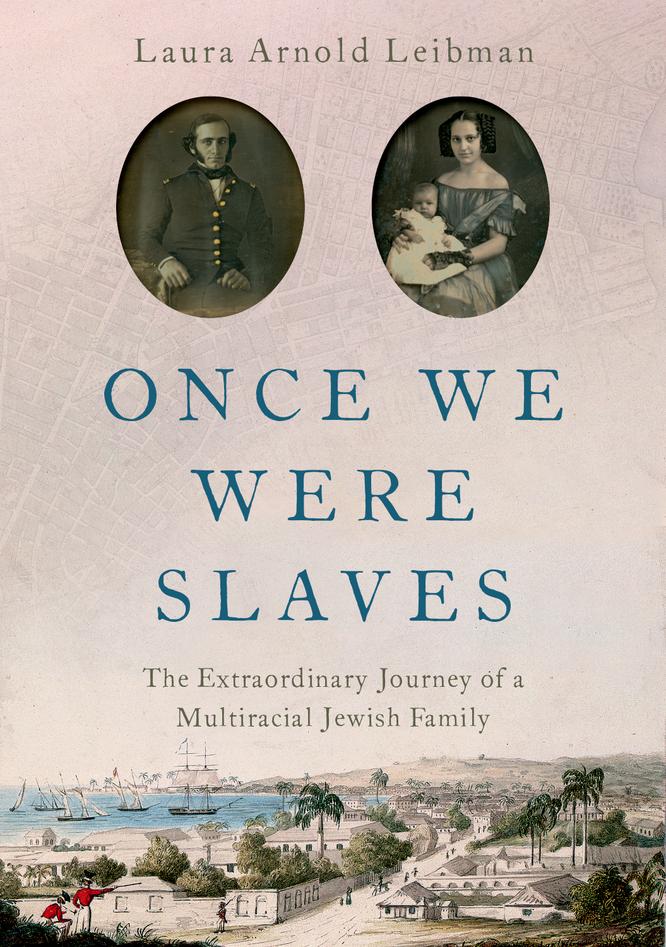

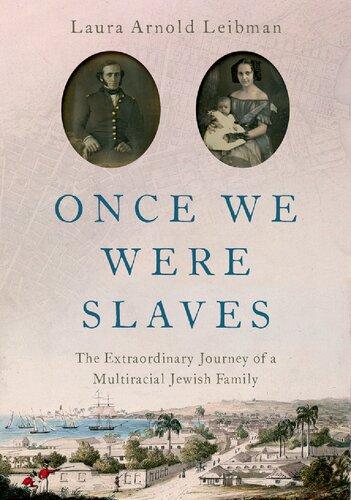

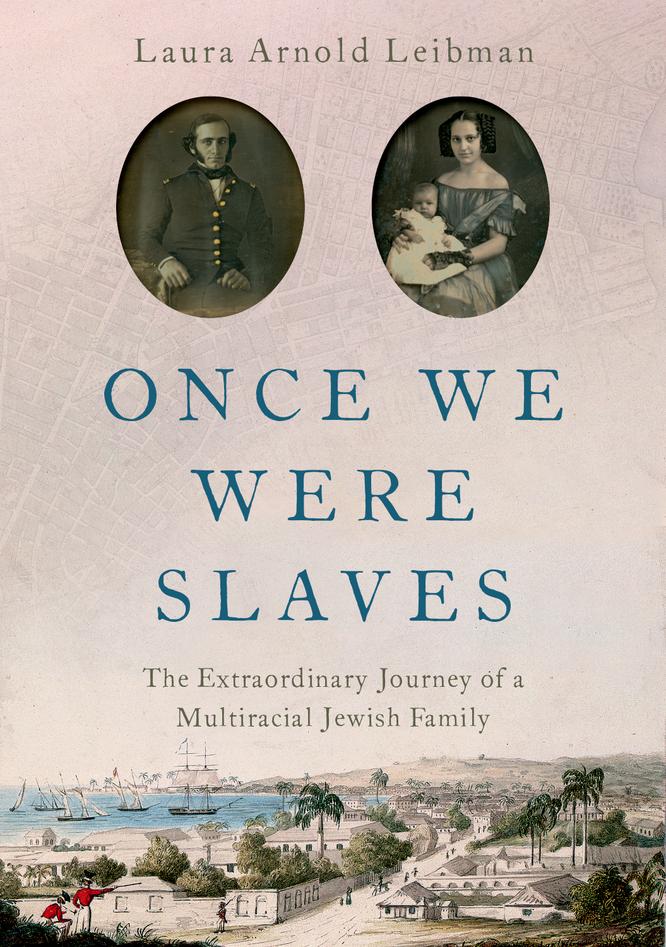

Title: Once we were slaves : the extraordinary journey of a multiracial Jewish family / Laura Arnold Leibman.

Other titles: Extraordinary journey of a multiracial Jewish family

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021016423 (print) | LCCN 2021016424 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197530474 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197530498 (epub) | ISBN 9780197530627

Subjects: LCSH: Jews—New York (State)—New York—History—19th century. | Moses, Sarah Brandon, 1798–1828. | Brandon, Isaac Lopez, 1793–1855. | Brandon family. | Moses family. | Jews—Barbados—Bridgetown—History—19th century. | Racially mixed people—New York (State)—New York—History—19th century. | Racially mixed people—Barbados—History—19th century. | Bridgetown (Barbados)—Biography. | New York (N.Y.)—Biography.

Classification: LCC F128.9.J5 L45 2021 (print) | LCC F128.9.J5 (ebook) | DDC 974.7/100405924096972981—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021016423

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021016424

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197530474.001.0001 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by LSC communications, United States of America

Once we were slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt, and now we are free.

Avadim Hayinu, Passover Hagaddah

1. Origins (Bridgetown, 1793–1798) 1

2. From Slave to Free (Bridgetown, 1801) 18

3. From Christian to Jew (Suriname, 1811–1812) 27

4. The Tumultuous Island (Bridgetown, 1812–1817) 46

5. Synagogue Seats (New York and Philadelphia, 1793–1818) 57

6. The Material of Race (London, 1815–1817) 74

7. Voices of Rebellion (Bridgetown, 1818–1824) 93

8. A Woman of Valor (New York, 1817–1819) 102

9. This Liberal City (Philadelphia, 1818–1833) 114

10. Feverish Love (New York, 1819–1830) 125

11. When I Am Gone (New York, Barbados, London, 1830–1847) 143

12. Legacies (New York and Beyond, 1839–1860) 159 Epilogue (1942–2021) 178

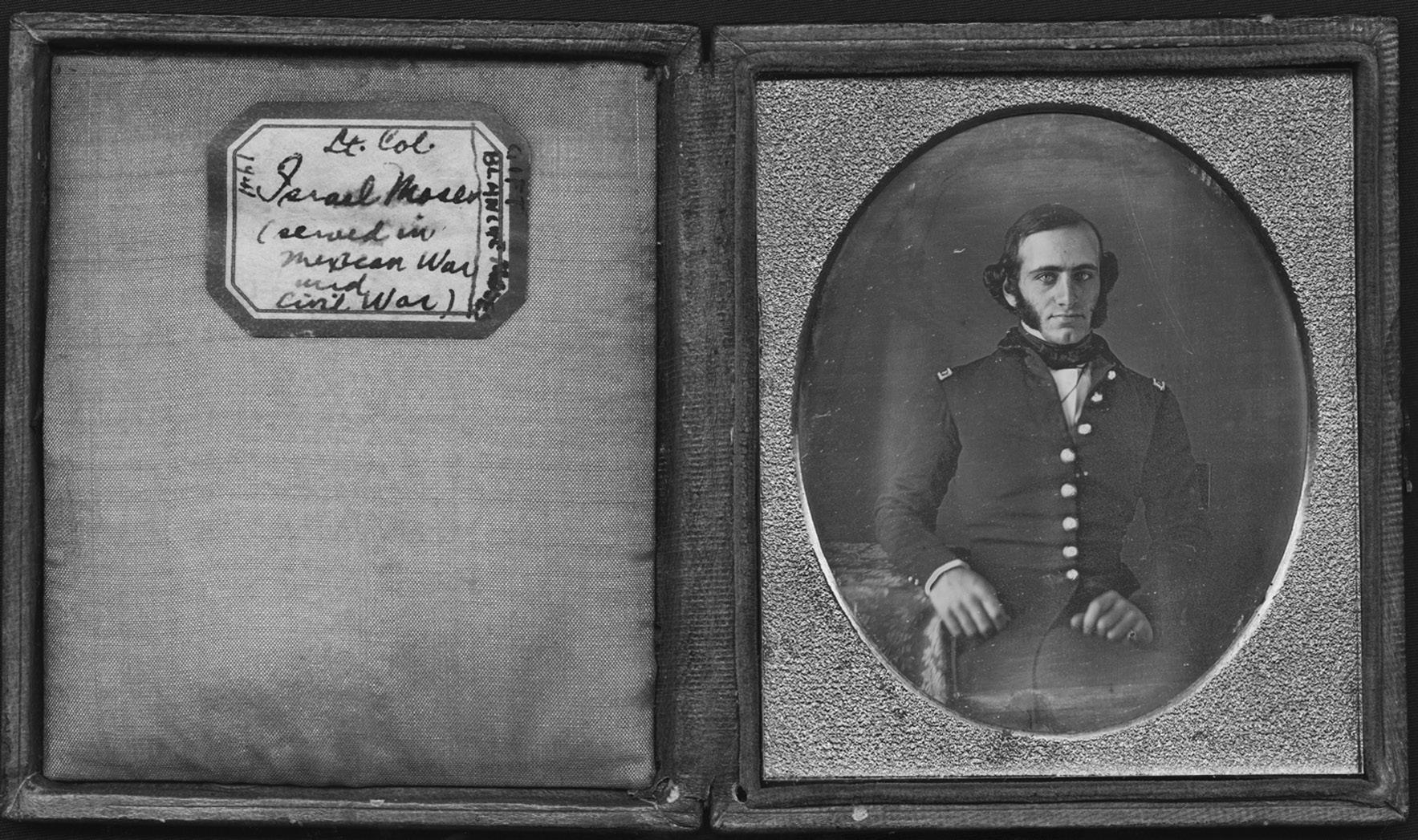

On January 4, 1942, Blanche moses was sitting in her “high quarters” at 415 West 118th Street in New York City, writing yet another letter to Rabbi Meyer, the librarian at the American Jewish Historical Society. At eighty-two, the reclusive heiress was losing her patience. Her collection of daguerreotypes—“one of my precious possessions”—had been lost while on loan, and she was unable to get into the library to look for the family keepsakes. She begged Rabbi Meyer for assistance. As she noted, she hoped to have his help, as she preferred “not to court personal publicity.” This was something of an understatement. As Moses explained when she gave the rabbi the number for her newly installed phone, she could be “reached at any hour—day or evening, as I do not go out.”1

Blanche Moses’s letter came three weeks after Pearl Harbor, and despite her obsession with the objects of her ancestors, Moses was not immune to the impending war. Her building was in the process of being fitted for possible alert. Her upper-story apartment with its exposed walls was conventionally more desirable, but now was “being considered quite unsafe” in event of airstrikes. Hence, she and her collection were moving down to a lower floor.2

Rabbi Meyer was apparently able to help Moses, because today the daguerreotypes are safe as part of the collection of the Moses and Seixas Family Papers at the American Jewish Historical Society. The daguerreotypes

include stiff portraits of Moses’s uncles in Civil War uniforms and her beautiful young mother Selina Seixas in lacy fingerless gloves (all the rage in 1854), her braided hair wound in heavy loops on the sides of her head like a Victorian Princess Leia. Today the daguerreotypes are reunited with other family portraits, including photos from Moses’s own childhood, such as several of her beloved sister Edith in blond ringlets and Blanche herself, characteristically pouting with her dolls. They are portraits of a lost era, a time when the Moses family prospered in the young nation. When Blanche Moses died in 1949, the war was over. The photos, along with her family’s other memorabilia, became part of the collection of the oldest ethnic historical society in the United States.

Moses would be pleased with the collection’s treatment. The descendant of some of the earliest Jewish families to settle in the country, she wanted to leave her priceless collection to a Jewish archive, but her letters suggest she equally wanted to ensure that the objects would receive the love she herself afforded them. The American Jewish Historical Society of the twenty-first century bears little resemblance to the library that temporarily misplaced her collection of daguerreotypes. Once run by volunteers, today AJHS is a flagship for preservation standards. The Moses and Seixas collections are cherished and well maintained.

In an elegant, climate-controlled building on West 16th Street, the Moses collection nestles among the donations of other families who have been eager

to preserve the past. After all, Blanche Moses was not the only American Jew on the eve of the Holocaust who felt desperate to look back in solace on days gone by. Today, genealogy is the second most popular hobby in the United States after gardening. Few of us are as lucky, however, as Moses in having such an illustrious family to study. Among her possessions were items relating to two of her great-grandfathers. The first, the Reverend Gershom Mendes Seixas, oversaw New York’s and Philadelphia’s earliest synagogues for nearly fifty years and was one of Shearith Israel’s most beloved spiritual leaders. The second, Isaac Moses, was a Revolutionary War hero and real estate tycoon who balanced religious devotion with administering a vast mercantile empire.3

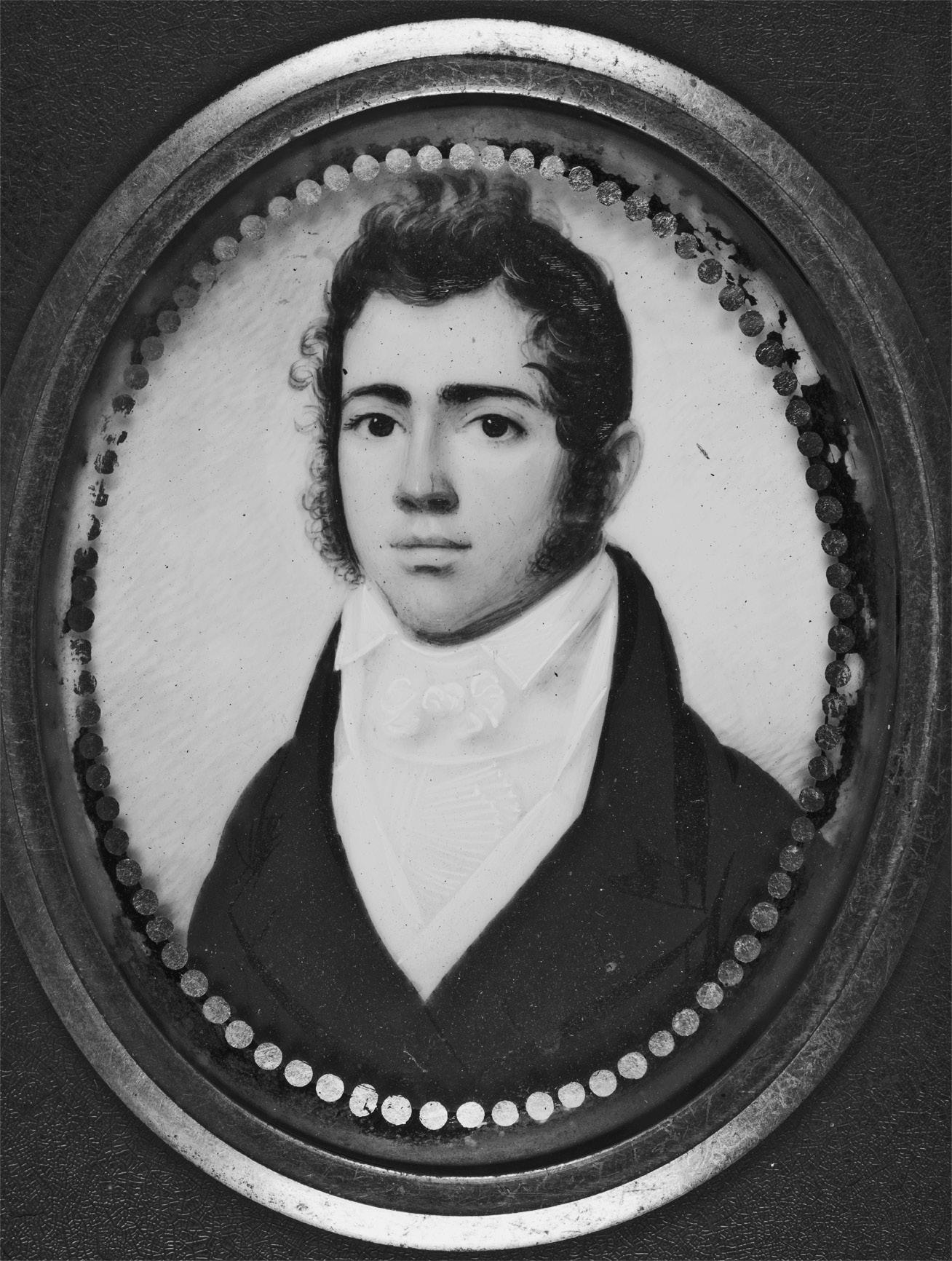

Yet even Moses would be surprised by recent interest in two of the artifacts she donated. Amid the memorabilia of eminent men are two ivory miniatures, painted in watercolor, depicting relatives Blanche Moses never met and knew almost nothing about: her great-uncle Isaac Lopez Brandon (1793–1855), and her grandmother Sarah Brandon Moses (1798–1829), a woman who died thirty years before Blanche was born, and a mere ten days after Blanche’s father’s third birthday.

Moses certainly knew scraps about Sarah and Isaac’s past. Their father was a given: all available records pointed to Abraham Rodrigues Brandon of Barbados, the island’s wealthiest Jew. Yet despite being a meticulous family historian who regularly corrected articles appearing

in the New York Times and American Jewish Historical Society’s scholarly journal, Moses drew an uncharacteristic blank when it came to her grandmother and great- uncle’s maternal line. Who was their mother? Moreover, why was so little known about her, when she had married a man so famous? 4

When it came to Sarah and Isaac’s early life, the documents that typically cluttered Blanche Moses’s apartment were absent. This was bad news. Moses was Sarah’s only grandchild who was still alive, and all of the family papers had slowly funneled down to Moses’s apartment on the Upper West Side. Moses was left to guess about Sarah and Isaac’s background. “Abraham Rodrigues Brandon Barbados,” Moses scribbled on the margin of one paper, “married Sarah Esther?”5 Even Malcolm Stern, the premier genealogist of

Blanche Moses’s grandmother.

Anonymous, Portrait of Sarah Brandon Moses (ca. 1815–16).

Watercolor on ivory, 2 3/4 x 2 1/4 in. AJHS.

early American Jews, could do no better. Using information from New York’s Shearith Israel synagogue about Moses’s great-grandmother’s death in 1823 in New York, he too could only conjecture about Sarah Brandon Moses and Isaac Lopez Brandon’s mother, speculating she was part of the Lopez clan of Barbados.6

They were both wrong.

Moses and Stern were right about one small thing, though. Moses’s greatgrandmother had been raised in the Lopez household and she sometimes used their last name. She gained the surname Lopez, however, not as a child born into the family, but because she was enslaved by them. Moses’s grandmother Sarah and her great-uncle Isaac had also begun their lives poor, Christian, and enslaved in the late eighteenth-century Lopez household in Bridgetown, Barbados. Within thirty years, Sarah and Isaac had reached

Blanche Moses’s great-uncle. Anonymous, Portrait of Isaac Lopez Brandon (early nineteenth century). Watercolor on ivory, 3 1/8 x 2 1/ 2 in. AJHS.

the pinnacle of New York’s wealthy Jewish elite. Once labeled “mulatto” by their own kin and by the Anglican church in Barbados, by 1820 Sarah and her children had been recategorized as white by New York’s census. Likewise, Isaac was accepted as white by the New York Jewish community, who helped him gain citizenship. What makes this change all the more surprising is that it was not a secret. Although it was a mystery to Sarah’s granddaughter, Sarah and Isaac’s partial African ancestry was known by numerous people everywhere they lived. Sarah and Isaac’s ability to change their lives and their designated race—despite this knowledge—tells us as much about the early history of race in the Atlantic world as it does about the lives of early American Jews.7

Today the small portraits of Sarah Brandon Moses and her brother Isaac Lopez Brandon are understood to be among the rarest items owned by the historical society, as they are the earliest known portraits of multiracial Jews. For over two centuries, the remarkable story of Sarah and Isaac lay buried in archives across three continents. Were it not for a small, random footnote about Isaac’s ancestry in the records of Barbados’s Nidhe Israel synagogue, the cocoon of assumptions obscuring their past might have remained intact. They would have forever been the lesser-known members of an illustrious family.

But sometimes the people we know the least about turn out to be the most interesting. This book traces the extraordinary journey of Sarah and Isaac as they traveled around the Atlantic world. In the process, they

changed their lives, becoming free, wealthy, Jewish, and—at times—white. They were not alone. While their wealth made them unusual, Sarah and Isaac were not the only people in this era who had both African and Jewish ancestry. The siblings’ story reveals the little-known history of other early multiracial Jews, which in some of the places the Brandons lived may have made up as much as 50 percent of early Jewish communities. Until now, that story was largely hidden from history, wrapped in the tissue of the past, like the delicate portraits of Sarah and Isaac, swaddled in acid-free paper in a box in the depths of an archive. This book is their unveiling.8

Years later, Abraham Rodrigues Brandon would claim that his daughter Sarah had always “professed our holy religion.”1 Technically that was not true. Sarah Brandon was baptized as an Anglican at Saint Michael’s Church in Bridgetown, Barbados, on June 28, 1798. The faded ink of the record book would become the first documentation of either her or her brother Isaac’s life. It was also the start of a series of distortions that would harrow the siblings’ ascent through the ranks of wealthy Jewish society.2

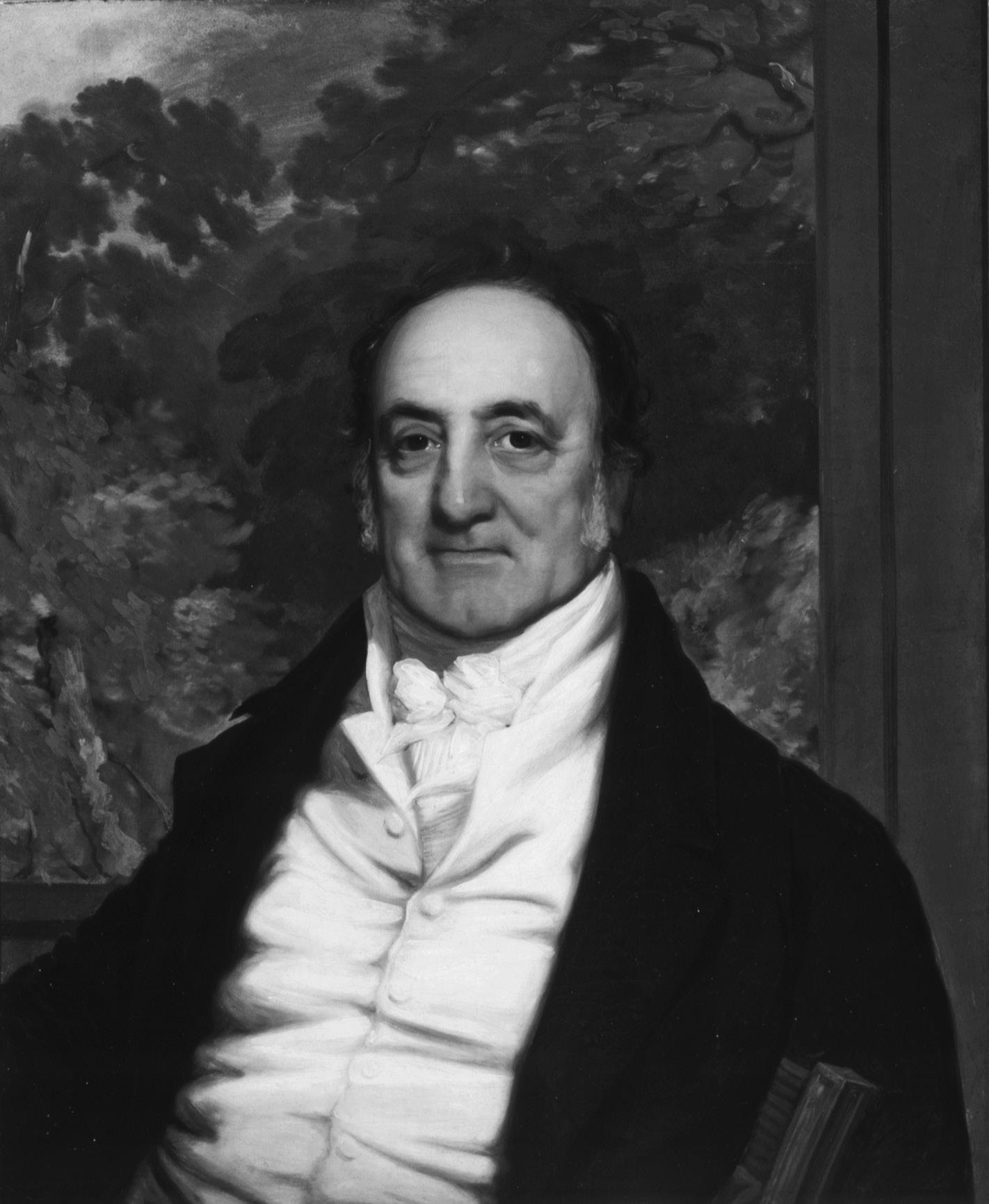

Brandon’s white lie was typical of his relationship with Sarah and Isaac. Brandon was nothing if not ambitious. When Sarah was born, he was just over thirty and a minor player in the island’s economy and synagogue. His earliest portrait is a fashionable ivory miniature, showing him in a velvet frock coat and the hedgehog hairstyle popular in the mid-1780s. The bright blue of the velvet, along with the large golden buttons, signaled an aristocratic dignity. Yet the portrait is amateurish compared to the later miniatures of his children. The portrait’s wishful thinking is reflected in what else we know of Brandon from the era. In the 1780s and early 1790s, Brandon rarely appears in synagogue records or in the Levy books of St. Michael’s parish, suggesting he neither owned property in town nor was the primary renter of an establishment. Taken as a whole, Brandon’s early self-presentation is more aspiration than arrival.3

Yet by the time of his daughter’s death in 1828, Brandon had become the most influential Jew in Barbados. When Brandon had a second portrait made around 1824, he had more than realized his earlier dreams. The

portrait was larger (nearly three feet tall rather than a few inches) and painted by New York’s premier portrait artist, John Wesley Jarvis. Behind Brandon stands a rich pastoral scene (albeit one of New England) that called to mind that he was now not merely a successful merchant but also the owner of three prosperous labor camps: Hopeland, Dear’s, and Reed’s Bay, where at least 168 enslaved people had worked in 1817. Brandon also now ruled the island’s synagogue, first becoming a member of the Mahamad the governance board—in 1796 and then the synagogue’s Presidente in 1810.4

Whatever longing had driven Brandon to success, at least one eye was on his future line. His support helped his oldest children rise up through the social ranks alongside him. In this way he was probably the best of parents: even at his death he left a note explaining to Isaac that the hefty

sum Isaac inherited would have even been more if the recent depreciations of West Indian property had not diminished Brandon’s wealth. The inheritance was still twice what Sarah and Isaac’s much younger half-siblings would receive.5 Brandon likewise asked Barbadian Jews to see his son as an equal, and when some of his fellow Jews refused, the president of the synagogue reported that they “inflicted a wound that stings Mr. Brandon to the quick.”6 Words against Isaac became an “envenomed dart which rankles in the bosom of Mr. Brandon . . . lacerat[ing] his feelings.”7 No wonder, synagogue president Benjamin Elkin explained, Brandon had decided to absent himself from the synagogue in their wake.

Yet while Abraham Rodrigues Brandon’s relationship with the siblings’ mother would last more than thirty-five years, he used the white man’s prerogative not to marry (Sarah) Esther, who like her children had been born enslaved. Brandon would persist in this decision, even when the family moved off island to places where an interracial marriage was technically possible if not completely accepted. Brandon’s resolution would continue to haunt Sarah and Isaac’s lives, affecting their racial and social status as they moved about the Atlantic world.

Just as Brandon later hedged about his daughter’s religious history, so too was something off in the original church records. Although the record keeper listed Sarah as a “free Mulatto,” that was a dodge.8 Like her brother Isaac, Sarah was born enslaved, and she would not become free until the nineteenth century dawned, her manumission detailed in the record books of the same church where she had been baptized. Although Isaac’s own accounting suggests he was born five years earlier, in 1793, his birth went unrecorded. This was not unusual: before 1800, people of African ancestry were rarely baptized on the island, and slave records were spotty at best.9

Equally strange as being listed as a “free Mulatto” is the fact that Sarah carried her father’s rather than her owner’s last name. Back when Sarah was born, Brandon’s willingness to admit paternity at all was unusual: most white fathers in Barbados failed to recognize their children with women of color, refusing to give their children their last name, let alone emotional or monetary support. Yet despite the open suggestion of paternity in the church records, early on Sarah and Isaac did not share their father’s home. They resided instead with the Lopezes, who enslaved many of the siblings’ kin. Like the Brandons, the Lopezes were Jewish refugees of the Inquisition.10

Despite their differences, persecution had brought both sides of Sarah and Isaac’s clan—as well as that of their owners—to the tropical island. The promise of riches had drawn or forced immigrants westward toward the

island’s central crop: sugar. Today the average American consumes roughly 152 pounds of sugar a year, or three pounds a week. In contrast, in the medieval era, sugar cost as much per ounce as silver. Sugar was still a luxury reserved for nobles in the sixteenth century, and was sometimes molded into large, elaborate sculptures that conspicuously displayed their owner’s wealth. By the seventeenth century, widespread production in places like Barbados made sugar available to the middle class. By the middle of the nineteenth century, sugar prices would drop further so that even the poor could put the white gold in their tea. This is only one way of measuring the cost of sugar, however. As a Surinamese slave explained in Voltaire’s Candide, “When we work in the sugar mills and we catch our finger in the millstone, they cut off our hand; when we try to run away, they cut off a leg; both things have happened to me. It is at this price that you eat sugar in Europe.”11

Born enslaved, Sarah and Isaac would have been keenly aware of the cost of sugar. In the 1790s, enormous mahogany trees still grew on some of Barbados’s highest hills, but sugar cane fields filled most of the island’s 166 square miles. The vast majority of residents were enslaved, outnumbering white Barbadians by four to one. Most worked in the cane fields. It was terrible work. As early as the 1650s, the Irish indentured servants brought to work the fields complained of being “used like dogs . . . grinding at the mills and attending the furnaces, or digging in this scorching island.”12 Even after arriving in Barbados, neither enslaved nor indentured servants had a guarantee of family life. In a petition to the English Parliament, indentured servants in Barbados complained about how they had been “bought and sold still from one planter to another, or attached as horses and beasts for the debts of their masters, being whipt (as rogues) for their masters’ pleasure, and sleeping in sties worse than hogs in England.”13

Plantation owners eventually ameliorated the working conditions of Irish servants, but only by replacing their labor with that of enslaved West Africans. DNA evidence from one of Isaac’s descendants suggests the siblings’ ancestors came from the region of Africa known today as Nigeria, the homeland of the Hausa, Yoruba, Igbo, and 350 to 450 other ethnic groups. Those ancestors also had genetic connections to people living today in Eastern and Southern Africa. This spread suggests that either the siblings had ancestors from multiple regions of Africa or (more likely) their ancestors belonged to the Bantu peoples originally from what is now Nigeria, as the Bantu would later spread across the continent.14

If those ancestors were Bantu, they were not alone in experiencing slavery. At the time when Sarah and Isaac’s ancestors were captured, Europeans

referred to the Bantu homeland as the Bight of Biafra. Eventually more than 1.6 million people were forced to endure the terror of the transatlantic slave trade from this region alone. They made up about 13 percent of all enslaved Africans in the Americas. Many were sold in Barbados: by the end of the seventeenth century, nearly half of all enslaved people arriving in Barbados had been captured in the Bight of Biafra, with many others coming from the nearby Bight of Benin. The flags dotting the coastline in maps of the era speak to Europeans’ horrific rush to profit from the slave trade and the decimation of the area.15

Unlike the Irish, who had to serve out only a limited number of years before being freed, Africans transported to Barbados served for life. Work like cane holing—the readying of the soil for planting cane tops—took such a toll on enslaved people’s bodies that some planters rented other people’s slaves to do the brutal work rather than destroy the bodies of their own slaves, which, after all, were a form of investment for the owners.

Even being an investment, however, did not save enslaved people from having to feed cane into the enormous rollers that pressed out the sugar juice. If a slave pushed her hand in too far, she—like the slave in Candide would get caught in the press, rolled inward to her excruciating death. Sometimes heads were severed from bodies. Overseers kept a hatchet next to the press to cut off trapped limbs. It was not uncommon to see enslaved people in Barbados—many of them women—missing fingers, hands, or arms. From the 1810s to the 1830s, this was the kind of work enslaved people performed in the labor camps Abraham Rodrigues Brandon owned.16

Sarah and Isaac’s African ancestors who had been forcibly transported across the Atlantic were most likely originally brought to Barbados to work in the cane fields. But by the middle of the eighteenth century, the family found itself living in the main port of Bridgetown as part of the urban enslaved. Being an urban slave exempted one from the painful labor of the cane fields, but it brought its own hardships. Half of the enslaved people in town were domestics who undertook the arduous work of washing, cleaning, cooking, and child care in the tropical heat. Many others were jobbed out by their owners, working in the shipyards, or as fishermen, laborers, transport workers, or hucksters who wandered between town and countryside selling goods.17

Enslavers also unabashedly hired out enslaved women for sexual purposes. Some were forced to work in the city’s brothels, including hotels run by free women of color. Others were hired out by owners on a less formal basis to sailors and townsmen. According to a British naval officer stationed on the

island, even respectable women who hired out enslaved women for jobs such as washing clothes assumed that the inflated price they charged would include sexual benefits for the men doing the hiring. The officer noted that one enslaver “lets out her negro girls to anyone who will pay her for their persons, under the denomination of washerwoman, and becomes very angry if they don’t come home in a family way.”18

Women like Sarah and Isaac’s mother and grandmother often sought refuge in longer-term sexual relationships with whites who might discourage owners from selling their bodies to random men. These relationships, however, were also not always voluntary, nor were they equal partnerships. Just as the siblings’ mother (Sarah) Esther Lopez-Gill had a long relationship with the Sephardic Jew Abraham Rodrigues Brandon, so too their grandmother Jemima Lopez was the mistress of a British man named George Gill.

Like his father before him, Gill was a schoolmaster and a devout Anglican. Although the Europeans on the island obsessed over how enslaved people were “addicted” to polygamy, adultery, and sex, white men like Gill typically had multiple extramarital relationships with women of color without any fear of being censured by the Anglican church.19 Certainly, there was no expectation that Gill would marry Jemima Lopez, despite having four children with her. Although interracial marriage was technically not illegal, there is only one known instance of a church marriage between a white person and a person with African ancestry in Barbados during the era of slavery. That marriage took place in the seventeenth century, more than a hundred years before the Brandon siblings were born. The imbalance between Gill and Jemima Lopez was further underscored by the fact that Jemima Lopez was one of several Afro-Barbadian women who bore Gill’s children.20

Sarah and Isaac’s family was matriarchal, like that of most urban enslaved families. Female and urban enslavers tended to buy women, both because they were cheaper to purchase than men and because they gave a high return on one’s investment. As a case in point, the siblings’ great-grandmother Deborah Lopez was the matriarch of at least ten descendants born in bondage to the Lopez family. Born in 1798, Sarah Brandon, daughter of (Sarah) Esther Lopez-Gill, daughter of Jemima Lopez-Gill, daughter of Deborah Lopez, was the youngest of this enslaved family.21

Unlike Sarah’s father, neither Sarah’s mother nor her grandmother nor her great-grandmother had their portraits painted. Everything we know about these women is biased by the violent way the archives erase certain lives and privilege others. (Sarah) Esther Lopez-Gill’s story is similar to those

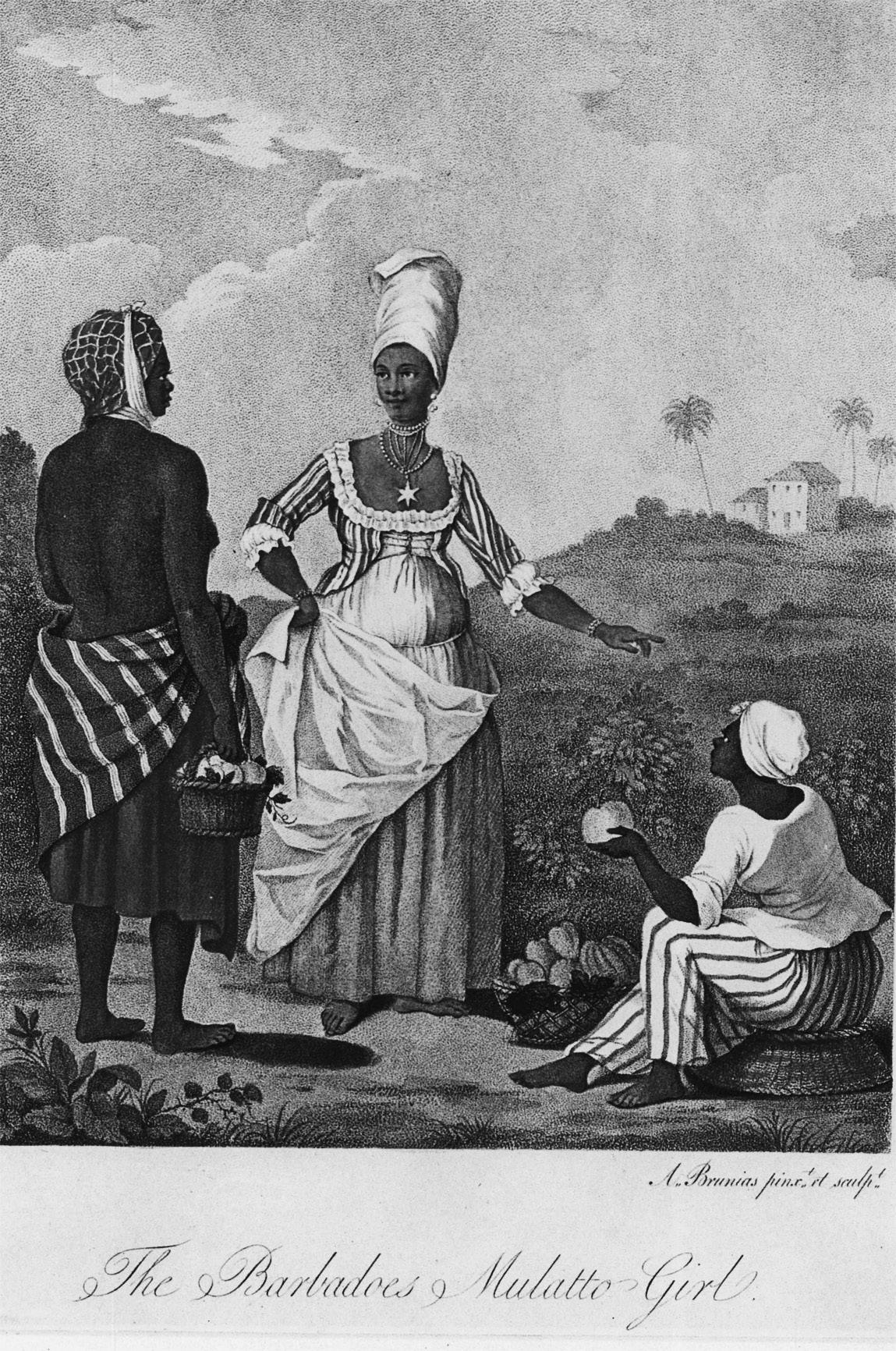

of so many enslaved women in the Caribbean in that her experiences were written down at the time by flawed witnesses, who transcribed nothing she said and didn’t wonder about what she thought. Like many enslaved women in Barbados, most of what we know about the matriarchs of Sarah Brandon’s family is through the lens of whites, men such as London-based painter Agostino Brunias, who traveled and lived in the West Indies in the 1760s–1790s, painting sensual portraits of multiracial women, typically for wealthy plantation owners. Portraits of women like (Sarah) Esther LopezGill almost always failed to record the names of the women depicted. They were works like Brunias’s 1779 The Barbadoes Mulatto Girl, which depicted types, not specific people.22

In The Barbadoes Mulatto Girl, the category of woman presented is a radiant Venus. The woman is painted for the viewer’s pleasure, in a classic contrapposto pose with her weight placed on one leg, the S of her torso calling attention to her womb. One hand lifts her apron, as if she desires to expose herself, even as her skirt hides her legs. Although labeled a “girl,” she is all woman, pregnant, with a star drawing our attention to her bustline. Like the mango she is offered, the woman symbolizes fertility. Brunias parallels her production and that of the island’s labor camps by positioning her finger to draw our attention to the nearby cane fields and plantation house. The darker-skinned women on either side of her are reduced to props, who center our gaze on the lighter-skinned woman’s face and body. And like Abraham Rodrigues Brandon’s early miniature, the painting reeks of aspiration, though here the aspiration is all Brunias’s, namely, his desire to present women of mixed ancestry as safe and beneficial to the colonial economy.

Yet everything we know about (Sarah) Esther Lopez-Gill suggests that her life was anything but safe. Although born enslaved, she gained her freedom and rejected attempts to pin her down to one thing. One name could not hold her. As her white father remarked, sometimes her first name was Sarah, sometimes Esther, sometimes Sarah Esther. Who decided when and what to call her? Did she have the ability to object? We do not even know what the versions of her name meant to her: was Esther—the Jewish bride of Persian King Ahasuerus—a hope for her future as a savior of her people? Was Sarah for the Jewish matriarch, who married Brandon and spawned a dynasty? I refer to her as (Sarah) Esther, in part so readers will not confuse her with her daughter, but mainly to emphasize the hubris of thinking we will ever truly know her. (Sarah) Esther’s last name was just as unstable as her first, shifting from Lopez to Gill to Brandon depending on who told her story in

No portraits remain of Sarah and Isaac’s mother. Paintings of multiracial women from Barbados during this era tend to be types, not individuals. Agostino Brunias, The Barbadoes Mulatto Girl, after painting (ca. 1764), published in London in 1779. BMHS.

the colonial records and who claimed her as kin. (Sarah) Esther Lopez-Gill’s fluidity and that of her close kin network among free and enslaved people would be crucial, as the siblings made their way in the world.23

For when Sarah and Isaac were born, they did not live alone with the Lopez-Gill matriarch. Their family also included (Sarah) Esther LopezGill’s three brothers—Jonathan, William, and Alexander George Gill—and Sarah and Isaac’s sisters, Rachel and Rebecca Brandon, both of whom died young. Although most of the family would eventually receive their freedom, Deborah Lopez was never freed. At her owner’s death in 1815, she was willed to her great-grandchildren to care for her in her dotage, the cost of manumission beyond their reach.24

If abduction brought the siblings’ African ancestors to Barbados, persecution combined with economic opportunities explained how their Jewish ancestors and enslavers had ended up on the island. Sarah and Isaac’s ancestors were Portuguese Jews, also known as Sephardim, from the Hebrew word for Iberia, Sepharad. After centuries of living under Muslim rule, the Jews of Spain were forced out by Isabella and Ferdinand, the new Catholic rulers. The Alhambra Decree of 1492 gave Spanish Jews four months to convert or leave and abandon any gold, silver, or minted money. While some fled to North Africa and the Ottoman Empire, many went to nearby Portugal. It was here that the Lopezes and Brandons settled.25

But their respite proved only temporary. In 1496, a marriage alliance with Spain led King Manuel I of Portugal to demand that all Jews in his realm convert. Those who chose exile were required to leave behind their children, a price few would pay. As time passed, some forced converts and their descendants became faithful Catholics. Others continued to practice what Judaism they could in secret, even as they publicly attended Mass, ever fearful of the Inquisition’s flames. Even those New Christians who practiced Catholicism faithfully were not safe. Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, whenever natural disasters or the economy caused unrest, the Inquisition blamed the conversos forced converts and their descendants. New Christians were rounded up, thrown in jail, and tortured into confessions. The motive to finger a converso as a heretic was high: half of the estate of anyone convicted would go to the church, the other half to the informant. Convicted conversos who refused to reconcile themselves to the church were ritually paraded in yellow sackcloths and large conical hats, then burned at the stake in public autos-da-fé. Scholars have suggested that the Inquisition made more Jews than it killed: according to the autobiographies of some of the interned, they first learned about Jewish rituals from the Inquisitors’ questions. For others, the punishments sparked a flame of defiance: if they were going to be punished anyway, why not commit the crime?26

Both the Lopez and Brandon families were swept up in purges by the Inquisition. The records in the Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo in Lisbon contain extensive accounts of their imprisonment, torture, and trials. When released, the families fled to Amsterdam, Hamburg, London, and France. These were men like João Rodrigues Brandão, a young merchant, who was imprisoned in the 1720s, forced to complete a public penance, then released. After gaining freedom, he married his brother’s stepdaughter Luisa Mendes Seixas. Conversos who maintained Jewish practices

in secret often married close relatives in order to ensure that their offspring would have Jewish bloodlines. Marrying relatives also allowed conversos to better predict whether a spouse would be sympathetic to Crypto-Judaism, sympathies which if revealed to the Inquisition could result in death. At various points João Rodrigues Brandão and Luisa Mendes Seixas’s parents, siblings, and children were imprisoned, tortured, and punished. They were lucky to survive: the Inquisition’s court in Coimbra sentenced 9,547 heretics between 1541 and 1781, more than 330 of whom were burned at the stake. By the 1760s, João Rodrigues Brandão and Luisa Mendes Seixas gave up on Portugal. They made their way to London, where they took Hebrew names and remarried according to the Jewish rite. João, now Joshua, and the other male members of the family underwent painful adult circumcisions. When Joshua’s brother, Abraham Rodrigues Brandão, died in 1769, his will mentioned relatives still living in Portugal as well as others in London and Bayonne, France.27

Other branches of the family fled Iberia to Protestant-run Amsterdam and Hamburg, where—like in London—they could practice Judaism openly. Economic opportunities then pushed the refugees farther west. By the late 1600s, branches of both the Lopez and Brandon families had made their escape to the British West Indies, hoping to make their fortune in the white gold.28

They were not the only Sephardic Jews to take the journey. Sephardim were key to Barbados’s sugar trade. Sugar was a tricky crop, and successful transformation of the cane into granulated sugar was no easy feat. Prior to planting sugar in the Americas, the Portuguese planted cane on São Tomé. Conversos exiled to the island off the African coast played a role in developing this industry. Conversos likewise helped transport Portuguese knowledge to early plantations in Brazil, where they sought refuge from the Inquisition. Early settlers included members of the extended Brandon clan. By 1590, nearly a third of all sugar mills in the Bahia region of Brazil were owned by New Christian families. When the Dutch invaded in 1624, they offered these families the chance to worship openly. The Jews stayed until 1654, when the Portuguese recaptured the Brazilian port of Recife. The refugees then spread across the Caribbean and up the North American coast to New Amsterdam. Those who settled in Barbados founded the Nidhe Israel synagogue and helped set up the island’s sugar plantations and refineries.29

Jewish involvement in the sugar production business proved to be short-lived. British planters became wary of the Jews’ success and used the Anglican-controlled legislature to limit the number of slaves Jews could

own, making it impossible for Jews to run their own plantations. By the time Sarah and Isaac’s father Abraham was a boy, most Jews made their livelihood as merchants and shopkeepers in ports like Bridgetown. Both Abraham Rodrigues Brandon and the siblings’ owners were merchants. Familial ties in Europe’s great cities were a tremendous boon for traders like Abraham Rodrigues Brandon, as kin in other ports helped provide reliable trading partners for the sugar he exported. Even smaller shopkeepers like the Lopezes, who mainly sold goods in town, benefited from transatlantic coreligionists who served as creditors or trustworthy suppliers for the goods they sold. Eventually Abraham Rodrigues Brandon would break this mold, but during the children’s early years he was still a small-time trader.30

Bridgetown was a superb place to be a merchant. Today Bridgetown may seem small to continental visitors, but in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, it was the flagship city of the British colonies. According to one late eighteenth-century visitor, Carlisle Bay—the main harbor for the city— was the Thames of the West Indies. The port held a dizzying array of ships. In one hour alone, another astonished visitor noted more than a dozen varieties of vessels: “English ships of war, merchantmen, and transports; slave ships from the coast of Africa; packets; prizes; American traders; island vessels, privateers, fishing smacks, and different kinds of boats, cutters, and luggers.”31 By the 1770s, the population of Bridgetown was larger than its rival Kingston to the north in Jamaica, and almost as large as Boston, dwarfed only by Philadelphia and New York. The vast wealth to be made through sugar also made Bridgetown phenomenally resilient. Although the city was nearly destroyed in the fire of 1766 and then in the hurricane of 1780, it was quickly rebuilt using enslaved labor. The fortune to be made in the island’s main port would dramatically shape the siblings’ lives.32

Most Bridgetown residents were Anglican, but Methodists and one of the largest Jewish American communities also called the port home. By the middle of the eighteenth century, 400 to 500 Jews lived in Barbados, almost all in Bridgetown. Two things brought Jews to that port: trade and the synagogue. At the town’s center, just north of the wharves, lay Swan Street, sometimes called Jew Street because of the number of Sephardic merchants living on it. Swan Street became one of the main shopping streets in the port, but it was also in easy walking distance of the Nidhe Israel synagogue—the Scattered or Exiles of Israel.33

Jews are commanded to pray with a minyan (quorum) of ten men; thus in the 1650s, the refugees from Dutch Brazil began construction on a house of worship, though later hurricanes and fires would require the synagogue

to be rebuilt. Like most early Sephardic congregations in the Atlantic world, the synagogue was part of a complex of structures that also included four houses: one for the rabbi or hazan (Torah reader), one for the ritual slaughterer, one for the beadle, and one for the female attendant who ran the ritual bath or mikveh. In addition, the complex housed the mikveh, the Jewish school, and—rather uniquely—the community cemetery. The synagogue itself was small but delightful, modeled on the much larger synagogues in Amsterdam and London. As in those buildings, women sat upstairs in the balcony, in a section that echoed the women’s court in Solomon’s Temple. Rich hardwoods from tropical rainforests were the material for the seats, Torah ark, and reader’s platform. On the four corners of the reader’s platform were carved pineapples, the universal symbol of hospitality. It was a place Brandon called home.34

It was also their enslaver family’s spiritual haven. The Lopezes had been central members of both Congregation Nidhe Israel and Tzemah David in nearby Speightstown, whose synagogue had been destroyed in 1739 in an antisemitic riot that began after a Christian claimed he had been maliciously slandered at a Jewish wedding. By the time Sarah and Isaac were