1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication

Data Names: Tarlau, Rebecca, author.

Title: Occupying schools, occupying land : how the landless workers movement transformed Brazilian education / Rebecca Tarlau.

Description: New York, NY: Oxford University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018045717 | ISBN 9780190870324 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780190870355 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Movimento dos Trabalhadores sem Terra (Brazil) | Education—Political aspects— Brazil | Education and state—Brazil. | Social movements—Brazil. | Land reform—Brazil. Classification: LCC LC92. B8 T37 2019 | DDC 306.430981—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018045717

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

I dedicate this book to Dona Djanira Menezes Mota (1948–2017) of Santa Maria da Boa Vista, Pernambuco, and to the tens of thousands of rank-and-file MST activists like her. Many of them will never hold an MST leadership position, but their daily struggles keep the movement an influential force throughout the country.

Dona Djanira with her daughter Edilane in their home on an MST settlement in Santa Maria da Boa Vista. Edilane is a long-time activist in the MST state education sector. August 2011.

Courtesy of author (with permission from Edilane Mota)

ILLUSTRATIONS

FIGURES

1.1 Collective Decision-Making Structure of MST Camps 48

1.2 Number of New Land Occupations, 1988–1998 60

1.3 Number of Families in New Land Occupations, 1988–1998 60

1.4 Number of New Families Issued Land Rights, 1988–1998 60

1.5 Regional Distribution of Families in Land Occupations, 1988–1998 61

1.6 Collective Decision-Making Structure of the MST’s National Movement 64

1.7 Collective Decision-Making Structure of the MST Education Sector 65

2.1 PRONERA Budget, 1998–2010 (in millions of reais) 105

3.1 Number of Families in New Land Occupations, 1995–2010 141

3.2 Number of New Families Issued Land Rights, 1995–2010 141

3.3 The MST’s Proposal for Institutionalizing Educação do Campo (Education of the Countryside) in the Ministry of Education 146

3.4 The Actual Institutionalization of Educação do Campo (Education of the Countryside) in the Ministry of Education 147

3.5 Number of Families in New Land Occupations, 2003–2016 162

3.6 Number of New Families Issued Land Rights, 2003–2016 162

MAPS

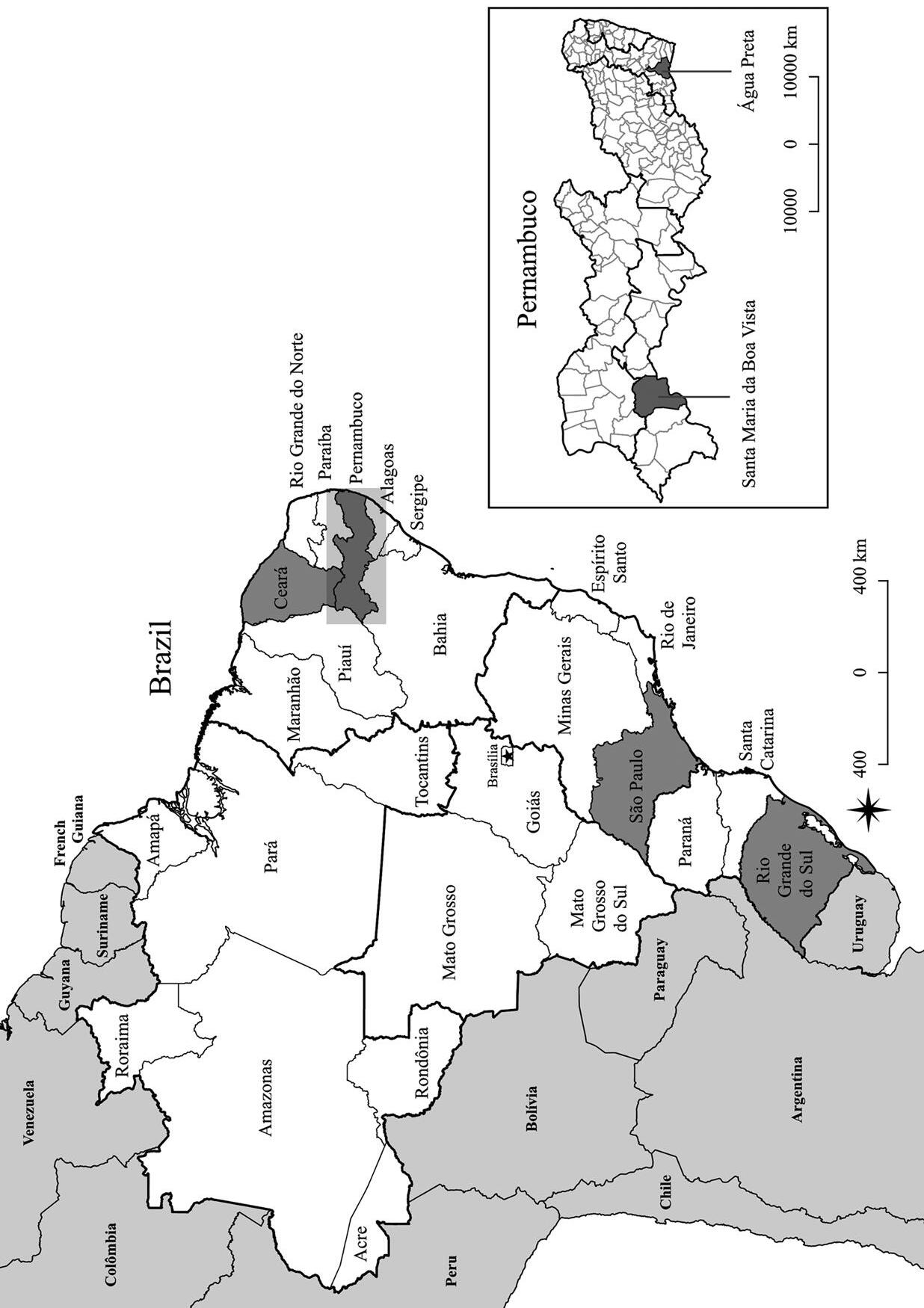

I.1 States in Brazil with Field Sites xxii

2.1 Geographical Distribution of PRONERA Programs Completed, 1998–2011 107

3.1 Location of Baccalaureate and Teaching Certification in Education of the Countryside (LEDOC) Programs in 2015 156

4.1 Geographical Location of State Public Schools in Data Set in Rio Grande do Sul 189

5.1 Locations of Santa Maria da Boa Vista and Água Preta 215

5.2 Municipal Public Schools Serving MST Settlements in Santa Maria da Boa Vista in 2011 221

6.1 High Schools Built on MST Settlements in Ceará, 2009–2010 261

TABLES

I.1 Barriers and Catalysts to the MST’s Contentious Co-Governance of Public Education 14

I.2 Case Studies of Institutionalizing the MST’s Educational Program Within the Brazilian State 26

1.1 National MST Educational Initiatives, 1987–1996 77

1.2 Pedagogical Foundations of the MST’s Educational Proposal 79

2.1 Number of PRONERA Programs Completed and Students Enrolled, 1998–2011 106

2.2 PRONERA Higher Education Programs Completed, 1998–2011 108

3.1 Conferences, Policies, and Coalitions Supporting Educação do Campo (Education of the Countryside), 1997–2012 168

5.1 Political Transitions and MST Educational Advances in Santa Maria da Boa Vista, 1995–2012 219

5.2 Political Transitions in Água Preta, 1988–2012 234

C.1 Barriers and Catalysts to the MST’s Contentious Co-Governance of Public Education: Regional Cases 291

PICTURES

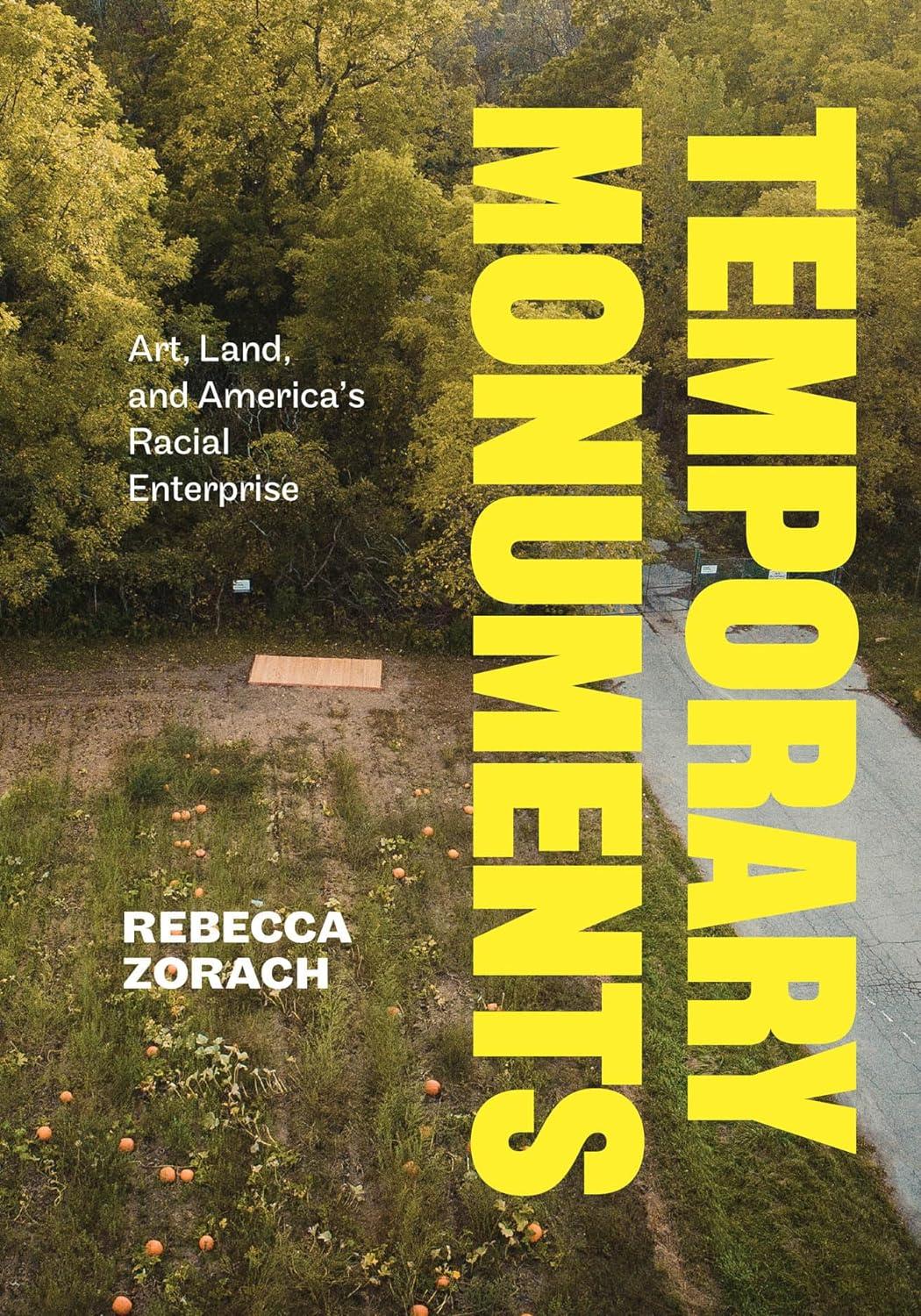

I.1 Students and educators from MST settlements and camps across the country protest in front of the Ministry of Education during the VI National MST Congress in Brasília. Their sign reads, “Little landless children against the closing and for the opening of schools in the countryside.” February 2014. 4

I.2 A student from the municipality of Santa Maria da Boa Vista, Pernambuco, paints the walls of the Ministry of Education in protest during the VI National MST Congress in Brasília. Her sign reads, “Little Landless Children in Struggle.” February 2014. 24

1.1 Students at IEJC/ITERRA perform a mística (cultural-political performance) celebrating the Soviet educator Anton Makarenko by recreating his image with beans and rice. September 2011. 75

1.2 Banner celebrating socialism hung on the outside walls of ITERRA/IEJC for the MST’s twenty-five-year anniversary. October 2010. 81

4.1 An Itinerant School functioning in the state of Rio Grande do Sul even after the government mandated the closure of all Itinerant Schools. June 2009. 201

4.2 Educators and students from MST settlements and camps across the state protesting the closing of the Itinerant Schools. The banner reads, “To Close a School Is a Crime, Little Landless Children in the Struggle for Education.” October 2010. 203

5.1 A teacher in front of a municipal public school in Santa Maria da Boa Vista, Pernambuco, located in the MST settlement Catalunha. The teacher is wearing her official municipal teacher uniform, which incorporates the MST’s flag. May 2011. 227

6.1 One of the four new high schools built on MST settlements in Ceará in 2009 and 2010 and officially designated as escolas do campo (schools of the countryside), November 2011. 265

7.1 Educators and activists at the Second National Meeting of Educators in Areas of Agrarian Reform (ENERA). A picture of one of the MST’s intellectual inspirations, Antonio Gramsci, is hanging in the back. September 2015. 283

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I arrived at my first MST settlement in June 2009 with a phone number and a notebook full of questions, and I embarked on the journey of a lifetime. Countless MST leaders embraced me as a fellow activist, put up with my endless questions and research requests, and welcomed me into their homes and at their meals. Among the many, I single out for special thanks Elizabete Witcel, Marli Zimmerman, and their families in Rio Grande do Sul; Cristina Vargas and her son Gabriel in São Paulo; Vanderlúcia Simplicio and her family in Brasília; Adailto Cardoso, Edilane Menezes, Erivan Hilário, and their families in Santa Maria da Boa Vista; and Flavinha Tereza, Alex Santos, and Elienei Silva in the mata sul region of Pernambuco. Alessandro Mariano became a close friend after I completed my data collection; however, our many conversations about the movement’s educational program greatly shaped the current book. I also want to thank all of the Brazilian government officials who accommodated my research requests, answering my probing questions about state–society relations calmly and thoroughly.

Many others made my research in Brazil possible by providing practical and moral support. Bela Ribeiro and her mother Rita have been my second family in Brazil ever since I first studied there as an undergraduate student. I counted on Bela’s home for food, rest, and comfort. Luis Armando Gandin and Bernardo Mançano Fernandes both served as my mentors while I was in Brazil. Lourdes Luna and Grupo Mulher Maravilha—a women’s organization on the periphery of Recife—were a powerful support system. It was Lourdes and the other women of this organization who first taught me about the transformational potential of popular education. If our paths had not crossed, I might never have discovered my passion for education. I also want to thank the organizations whose generous grants funded this research: the Social Science Research Council, the Inter-American Foundation, the Fulbright Institute of International Education, and the National Academy of Education.

At the University of California, Berkeley, I had an amazing dissertation committee that included Peter Evans, Zeus Leonardo, Erin

Murphy-Graham, Harley Shaiken, and Michael Watts. I want to give a special thanks to Peter Evans, who took me on as his own, despite his retirement from UC Berkeley and my sociology-outsider status. Peter has been a part of every step of this writing process, offering critical advice on theoretical frameworks, research design, making sense of data, developing arguments, and much more. Other UC Berkeley faculty who shaped my thinking about theory, politics, and research include Patricia Baquedano-López, Michael Burawoy, Laura Enriquez, Gillian Hart, Mara Loveman, Tianna Paschel, Dan Pearlstein, Cihan Tuğal, and Kim Voss. Outside of the Berkeley world, Pedro Paulo Bastos, Ruy Braga, Miguel Carter, Aziz Choudry, Gustavo Fischman, Sangeeta Kamat, Steven Klees, Pauline Lipman, David Meyer, Susan Robertson, Ben Ross Schneider, Andrew Schrank, Wendy Wolford, Angus Wright, and Erik Olin Wright have all offered feedback on different stages of this book project.

My friends from the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Education—all on the front line of the struggle against the privatization and dismantling of public education—contributed to countless iterations of this research, always reminding me to connect my findings to the US educational context. My deepest gratitude goes to Rick Ayers, Liz Boner, Krista Cortes, Chela Delgado, Tadashi Dozono, René Kissell, Tenaya Lafore, Joey Lample, Cecilia Lucas, Nirali Jani, Kathryn Moeller, Ellen Moore, Dinorah Sanchez Loza, Bianca Suarez, Joanne Tien, and Kimberly Vinall. I am also grateful to my interdisciplinary group of friends and colleagues, Edwin Ackerman, Javiera Barandiaran, Barbara Born, Javier Campos, Brent Edwards, Dave DeMatthews, Fidan Elcioglu, Luke Fletcher, Ben Gebre-Medhin, Ilaria Giglioli, Gabriel Hetland, Tyler Leeds, Seth Leibson, Zach Levenson, Roi Livne, Kate Maich, Diego Nieto, Ramon Quintero, Leonardo Rosa, Jonathan M. Smucker, Gustavo Oliveira, Karin Shankar, Krystal Strong, and Rajesh Veeraraghavan. Among my many supportive peers, Alex Barnard, Carter Koppleman, and Liz McKenna have been especially helpful in the final revisions of this manuscript. I am moved and inspired by Effie Rawlings’s dedication to making the MST’s agrarian vision a reality in the US context. I am grateful to Pete Woiwode for pushing me to think about lessons for US movements. Robin Anderson-Wood, Laurie Brescoll, Anna Fedman, Kirsten Gwynn, Sara Manning, Katie Morgan, Ashley Rouintree, Julia Weinert, and Rob Weldon have all kept me sane by reminding me to look up from my books, laugh, live, and dance. Bill, Nina, Jill, Kim, Margot, Hilary, Jo, and their families have been a source of love and support.

Transforming a doctoral dissertation into a book is a huge endeavor. I am grateful to Stanford University’s Lemann Center for Educational Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Brazil for the gift of time through a two-year postdoctoral fellowship. Martin Carnoy, my postdoctoral faculty

Acknowledgments ( xv )

sponsor, has been a huge advocate of this research. Georgia Gabriela da Silva Sampaio, a very talented Stanford undergraduate, was an enormous help in designing all of the book’s maps and many of the figures. I also want to thank the Stanford Center for Latin American Studies for cohosting a book workshop with the Lemann Center on a first draft of the manuscript. The feedback I received during the workshop led to a major revision of the book’s theoretical contribution and a much-improved organization of its empirical chapters. My sincere thanks to Martin Carnoy, Alberto Diaz-Cayeros, Gillian Hart, Mara Loveman, Tianna Paschel, Doug McAdam, and Wendy Wolford for participating in that day-long workshop. In January 2018, I joined the faculty of Pennsylvania State University’s College of Education and School of Labor and Employment Relations. I am thankful for the contributions and support of my new colleagues in the Lifelong Learning and Adult Education program and the Center for Global Workers’ Rights, for the feedback I received from the PSU social movement reading group, and for the work of my two graduate assistants Hye- Su Kuk and Carol Rogers- Shaw for preparing the index. Finally, thanks to James Cook and Emily Mackenzie at Oxford University Press and Javier Auyero the Global and Comparative Ethnography series editor, as well as the four reviewers whose feedback greatly improved the manuscript.

My political commitments and intellectual curiosity are a direct product of the family I grew up in. My mother, Eileen Senn, has been fighting for workers’ safety rights and racial justice her entire life, teaching me the importance of principled political actions. My father, Jimmy Tarlau, has been part of the labor movement for forty years, always showing through example how to build broad coalitions and support for economic justice. My stepmother, Jodi Beder, is a professional copy editor and offered feedback on every stage of writing, spending many hours helping me to find the means to communicate with nuance and clarity. Thanks also to my brother, Swami Adi Parashaktiananda, whose spiritual growth has been inspiring to watch.

As I prepared to turn in this final book manuscript, in July 2018, Manuel Rosaldo and I vowed our commitment and partnership to each other in the Santa Cruz redwoods in front of many friends and family, including nine MST activists. Manuel proposed two years before, in the home of educational activist Elizabete Witcel, in an MST settlement in the far southern state of Rio Grande do Sul. In his proposal he talked about the MST’s inspirational achievements and how he learned through my experiences that research can be a means of forming powerful human connections. Manuel has been by my side during the entire process of writing this book, constantly reminding me of the book’s political relevance. Manuel’s companheirismo, his friendship, support, love, critical feedback, and advocacy, have helped

to bring this book into fruition, while also making writing a more joyful process.

I want to end by thanking one more time all of the women, men, and children who compose the dynamic social movement we know as the Brazilian Landless Workers Movement (MST), and who have taught me so much about leadership, discipline, collective decision making, education, and the cultural aspects of political struggle.

ABBREVIATIONS

CEB Comunidades Eclesiais de Base (Ecclesial Base Communities)

CNA Confederação Nacional da Agricultura e Pecuária do Brasil (National Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock of Brazil)

CNBB Conferência Nacional do Bispos do Brasil (National Conference of Brazilian Bishops)

CNBT Coordenação dos Núcleos de Base da Turma (Class Coordinating Collective of Base Nuclei)

CNE Conselho Nacional da Educação (National Education Advisory Board)

CNE/CEB Conselho Nacional da Educação/Câmara da Educação Básica (Basic Education Committee of the National Education Advisory Board)

CONTAG Confederação Nacional dos Trabalhadores na Agricultura (Confederation of Agricultural Workers)

CPI Comissão Parlamentar de Inquérito (Congressional Investigation)

CPP Coletivo Política Pedagógica (Political-Pedagogical Collective)

CPT Comissão Pastoral da Terra (Pastoral Land Commission)

CRE Coordenadoria Regional de Educação (State Department of Education Regional Office—Rio Grande do Sul)

CREDE Coordenadoria Regional de Desenvolvimento da Educação (State Department of Education Regional Office—Ceará)

CUT Central Única dos Trabalhadores (Central Union of Workers)

DEM Democraticas (Democrats—previously the PFL)

DER Departamento de Educação Rural (Department of Rural Education—of FUNDEP)

( xviii ) Abbreviations

ENERA Encontro Nacional de Educadores da Reforma Agrária (National Meeting of Educators in Areas of Agrarian Reform)

ENFF Escola Nacional Florestan Fernandes (Florestan Fernandes National School)

FONEC Forum Nacional da Educação do Campo (National Forum for Education of the Countryside)

FUNDEP Fundação de Desenvolvimento Educação e Pesquisa (Foundation of Educational Development and Research)

IEJC Instituto de Educação Josué de Castro (Educational Institute of Josué de Castro)

INCRA Instituto Nacional da Colonização e Reforma Agraria (National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform)

ITERRA Instituto Técnico de Capacitação e Pesquisa da Reforma Agrária (Technical Institute of Training and Research in Agrarian Reform)

LDB Lei de Diretrizes e Bases de Educação Nacional (National Educational Law)

LEDOC Licenciatura em Educação do Campo (Baccalaureate and Teaching Certification in Education of the Countryside)

MAG Magistério, nível media, normal médio (High School Degree and Teaching Certification Program)

MDA Ministério do Desenvolvimento Agrário (Ministry of Agrarian Development)

MEC Ministério da Educação (Ministry of Education)

MST Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (Brazilian Landless Workers Movement)

NB Núcleo de base (Base Nucleus—small collective of families or students that form the organizational structure of camps and settlements and schools)

PDT Partido Democrático Trabalhista (Democratic Labor Party)

PFL Partido Frente Liberal (Liberal Front Party—changes name to Democrats in 2007)

PMDB Partido do Movimento Democrático Brasileiro (Brazilian Democratic Movement Party)

PPP Projeto Político Pedagógico (Pedagogical-Political Project—a school mission statement)

PRONERA Programa Nacional da Educação em Areas da Reforma Agrária (National Program for Education in Areas of Agrarian Reform)

PSB Partido Socialista Brasileiro (Brazilian Socialist Party)

PSDB Partido da Social Democracia Brasileira (Brazilian Social Democratic Party)

PSOL Partido Socialismo e Liberdade (Socialism and Liberty Party)

PSTU Partido Socialista dos Trabalhadores Unificado (Unified Socialist Workers’ Party)

PT Partido do Trabalhadores (Workers’ Party)

SECADI Secretaria de Educação Continuada, Alfabetização, Diversidade e Inclusão (SECAD pre-2010— Secretariat of Continual Education, Literacy, Diversity, and Inclusion)

TAC Técnio na Administrão dos Cooperativas (Technical Administration of Cooperatives)

TAC Termo de Compromisso de Ajustamento de Conduta (Term of Commitment to Adjust Conduct)

TCU Tribunal de Contas da União (Brazilian Federal Court of Audits

UnB Universidade de Brasília (University of Brasília)

UNDIME União Nacional dos Dirigentes Municipais de Educação (National Union of Municipal Secretaries of Education)

UNESCO Organização das Nações Unidas para a Educação, a Ciência e a Cultura (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization)

UNESP Universidade Estadual Paulista (State University of São Paulo)

UNICEF Fundo das Nações Unidas para a Infância (United Nations Children’s Fund)

Occupying Schools, Occupying Land

Map I.1 States in Brazil with Field Sites Courtesy of Georgia Gabriela da Silva Sampaio

Introduction: Education and the Long March through the Institutions

How do we maintain this movement? Negotiating with the state without being absorbed. —Antonio Munarim, member of the National Forum for Education of the Countryside (FONEC) I would not call it co-optation but rather a type of institutionalization. If you are there in the school but you are also in the struggle and connected to the larger debates, then this is good. It is only co-optation if you stop being connected to the movement

Erivan

Hilário, national leader in MST education Sector

“The Landless Children have arrived!” chanted some five hundred children, ages four to fourteen, as they stormed past armed security guards into the Brazilian Ministry of Education in the capital city of Brasília on February 12, 2014. They had traveled from rural communities across the country to defend Educação do Campo, Education of the Countryside, the right to schools located in the countryside with organizational, pedagogical, and curricular practices based on their rural realities. Over the previous two decades, this grassroots educational proposal, which promotes the sustainable development of rural areas and contests assumptions of the inevitability of rural-to-urban migration, has become institutionalized. In other words, the Brazilian state has formally adopted major components of the educational proposal through national policy, an office in the Ministry of Education, and dozens of federal, state, and municipal programs.1 Nonetheless, despite official acknowledgment of this educational approach, governments at all levels continue to shut down rural schools and consolidate public education in large urban centers. The children held signs denouncing this trend: “37 thousand schools closed OccupyingSchools,OccupyingLand:HowtheLandlessWorkersMovementTransformed BrazilianEducation. Rebecca Tarlau, Oxford University Press (2019). © Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190870324.003.0001

2 )

in the countryside.” “Closing a school is a crime!” “Landless Children for the opening of schools in the countryside!”

The five hundred protesting children were the sons and daughters of activists from the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra, the Brazilian Landless Workers Movement (MST). The MST is one of the most well-known and extensively researched social movements in Latin America.2 The movement has become a reference point for left-leaning organizations around the world due to its success in occupying land and pressuring the government to redistribute this land to poor families. Since the early 1980s, the MST has pressured the state to give land rights to hundreds of thousands of landless families,3 through occupations of privately and publicly owned land estates. These families live on agrarian reform settlements, where they have also won access to government services such as housing, roads, agricultural technical assistance, education, and health services. Additionally, tens of thousands of families continue to occupy land across Brazil, spending years living in plastic makeshift tents and fending off police attacks while waiting for the legal rights to this land.

The MST articulates its struggles in terms of three broad goals: land reform, agrarian reform, and social transformation. Although land reform is a central component of agrarian reform, the movement separates these two goals in order to highlight that the initial struggle for land through land occupations is only a first step in achieving agrarian reform—the resources for families to live sustainably on this land. Social transformation is the MST’s struggle for socialist economic practices and what the movement refers to as a popular (grassroots) democracy. This is one of the most radical goals of the movement, as activists openly denounce capitalism and celebrate historical attempts to construct socialism, from the Bolshevik Revolution to the socialist governments of Cuba and Venezuela. The movement’s vision of social transformation has also evolved over the past two decades to encompass women’s rights, including equal gender participation within the movement, the defense of indigenous lands, racial equality, and more recently, the celebration of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) working-class rights. Education is a critical component of achieving all of these political, economic, and social goals.

In the week before the children’s protest, 15,000 MST activists from across the country had traveled by bus to the capital city of Brasília to discuss the movement’s future at the MST’s Sixth National Congress. The Congress, which coincided with the movement’s thirtieth anniversary, exemplified the movement’s practice of collective leadership, which Miguel Carter describes as “a multidimensional, network-like organization, composed of various decentralized yet well-coordinated layers of representation and collective decision making” (Carter 2015, 400). Delegations of

a couple hundred to several thousand MST leaders arrived from twentyfour of the twenty-si x Brazilian states.4 Each state delegation organized itself into smaller collectives of several dozen activists, to oversee cooking, cleaning, and other basic tasks necessary to camp for the week. State delegations also sent members to participate in congress-w ide collectives, with themes such as agricultural production, education, youth, communications, and international relations. The agricultural production collective set up a large market in the middle of the tent-city, where state delegates sold produce and artisanal products from their communities. The youth collective brought together young people to participate in a parallel conference appropriate to their needs and interests. The grassroots organizing collective—front of the masses (frente de massa)—planned the march that would occur in the middle of the week, to denounce the government’s lack of support for agrarian reform. Other collectives focused on women’s issues, health, culture, and security, while an international relations collective hosted 250 international delegates.5

The protesting children were a demonstration of the central focus that education has had in the movement. In the early 1980s, during the first MST land occupations, local activists began experimenting with educational approaches in their communities that supported the movement’s broader struggle for agrarian reform and collective farming. These experiments included both informal educational activities in MST occupied encampments and alternative pedagogical practices in schools on agrarian reform settlements. As the MST grew nationally, these local experiments evolved into a proposal for all schools located in MST settlements and camps—w hich, by 2010, encompassed 2,000 schools with 8,000 teachers and 250,000 students. The MST also pressured the government to fund dozens of adult literacy campaigns, vocational high schools, and bachelor and graduate degree programs for more than 160,000 students in areas of agrarian reform, through partnerships with over eighty educational institutions. During the early 2000s, the MST’s educational initiatives expanded to include all rural populations in the Brazilian countryside, not only those in areas of agrarian reform. The proposal became institutionalized within the Brazilian state through national public policies, an office in the Ministry of Education, a presidential decree, and dozens of programs in other federal agencies and subnational governments. By 2010, the MST’s educational proposal—now known as Educação do Campo—was the Brazilian state’s official approach to rural schooling. Nonetheless, the implementation of the proposal varied widely by state and municipality.

During the MST’s Congress, the national education sector materialized the movement’s educational approach by organizing a childcare

( 4 ) Introduction

center—the Center Paulo Freire—that engaged around eight hundred children in activities that touched on the themes of collective organization, work, culture, and history.6 On the third day of the Congress, these five hundred sem terrinha (little landless children) learned about another component of the MST’s pedagogy— struggle—by participating in their own direct action: occupying the Ministry of Education and declaring their right to locally based schools. While the children occupied the Ministry, the head of the Educação do Campo office—an office created in 2004 as a result of MST mobilizations—tr ied to convince the Minister to meet with the children, assuring him that he would not be in any danger.7 After three hours, the Minister came outside and promised the children quality education in the countryside. The leaders of the national MST education sector were happy the children had the opportunity to see the power of their collective action; however, they also understood that the Minister’s words were empty promises if activists did not continue to engage in similar actions across the country, to demand the implementation of the MST’s educational program.

Picture I.1 Students and educators from MST settlements and camps across the country protest in front of the Ministry of Education during the VI National MST Congress in Brasília. Their sign reads, “Little landless children against the closing and for the opening of schools in the countryside.” February 2014. Courtesy of author

THE LONG MARCH THROUGH THE INSTITUTIONS, CONTENTIOUS CO- GOVERNANCE, AND PREFIGURATION

The MST’s relationship with the Brazilian state—which in this book is understood as an assemblage of organizations, institutions, and national and subnational government actors that often have contradictory goals—is complex and fraught with tensions. Since the MST’s primary demand is land redistribution, the movement has an explicitly contentious relationship with the Brazilian state, as families occupy land to pressure different government administrations to redistribute these properties to landless families. As the MST promotes agrarian reform through public resources, the MST also has a collaborative relationship with the state, promoting agricultural and educational policies that increase the development of rural settlements—an outcome that can help both the movement and the state itself. Finally, the relationship is fundamentally contradictory, as the MST pressures the capitalist state to support a project with the end goal of overthrowing or eroding capitalism, through the promotion of more collective, participatory, and inclusive political and economic relations. MST activists demand schools in their communities and communities’ right to participate in the governance of these schools, with the purpose of promoting alternative pedagogical, curricular, and organizational practices—a process I refer to as contentious co-governance. These practices encourage youth to stay in the countryside, engage in collective agricultural production, and embrace peasant culture. These educational goals are an explicit attempt to prefigure, within the current public school system, more collective forms of social and economic relations that advance the future project of constructing a fully socialist society.

In the following chapters, I tell this story of how a social movement fighting for agrarian reform developed an educational proposal that supported its social vision, and how activists have attempted to implement this proposal in diverse economic and political regions throughout the country—transforming both the state and the movement itself.8 Thus, the book is about how activists’ contentious co-governance of formal state institutions can support their larger struggles. I follow the MST through what German student activist Rudi Dutschke termed the “long march through the institutions” (Dutschke 1969, 249).9 Social movement leaders engage in the long march when they enter the state, helping to carry out the daily job of public service provision, while linking those actions to a broader process of social struggle and a long-term strategy for economic and political change. The goal is to work “against the established institutions while working within them” (Marcuse 1972, 56). This requires activists’ technical

and political skills in a wide range of areas, including production, communications, programming, health, and education.

Dutschke’s inspiration for pursuing this strategy came from his engagement with the texts of Antonio Gramsci, an Italian Marxist intellectual and activist writing about political parties, revolution, and the state in the 1920s and 1930s. One of the central questions Gramsci was trying to answer is why—contrary to Karl Marx’s predictions—revolution had succeeded in the less developed context of Russia but had failed in the more developed Western European nations. Gramsci sought to create a theory of the state that went beyond the traditional vision of the state apparatus as a unitary class subject; instead, he analyzed state power as a complex of social relations (Jessop 2001). Gramsci believed that while the Czarist regime in Russia had ruled based on pure domination and force, in most Western European nations the ruling class establishes hegemony: a combination of coercion and consent, whereby the ruling class convinces a range of social groups that its own economic interests are in the interests of all. This construction of consent takes place both through the realm of ideas and direct economic concessions.

Thus, rather than domination, the determining factor of hegemony is “intellectual and moral direction . . . the need to gain ‘consent’ even before the material conquest of power” (Santucci 2010, 155). Gramsci writes that “A social group can and, indeed, must already be a leader before conquering government power . . . even if it has firm control, it becomes dominant, but it must also continue to be a ‘leader’ ” (Gramsci 1971, 57–58). Gramsci’s concept of “intellectual and moral leadership” is critical for understanding the stability of any given hegemonic bloc, and why political organizations such as the MST must engage in a similar strategy to win over diverse groups to support their own economic and political goals.

Civil society, which includes but is not limited to political parties, print media, social movements, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), the family, and mass education (Burawoy 2003, 198), is the most important sphere of ruling-class leadership. However, civil society also has a contradictory relationship to the state. As Michael Burawoy (2003) points out, “Civil society collaborates with the state to contain class struggle, and on the other hand, its autonomy from the state can promote class struggle” (198). Civil society is simultaneously a space of contestation where social organizations form and an arena of associational activity where daily life is experienced (Tuğal 2009). Gramsci suggests that rather than revolutionaries engaging in a war of movement—a direct attempt to take state power—in the “West” it is necessary to engage in a war of position: a long struggle in the trenches of civil society, to find allies who support their political project. Thus, rather than reject state engagement, a Gramscian question would be: “What institutions (schools, community organizations, work councils, etc.) best facilitate the transformation of common sense into political