1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

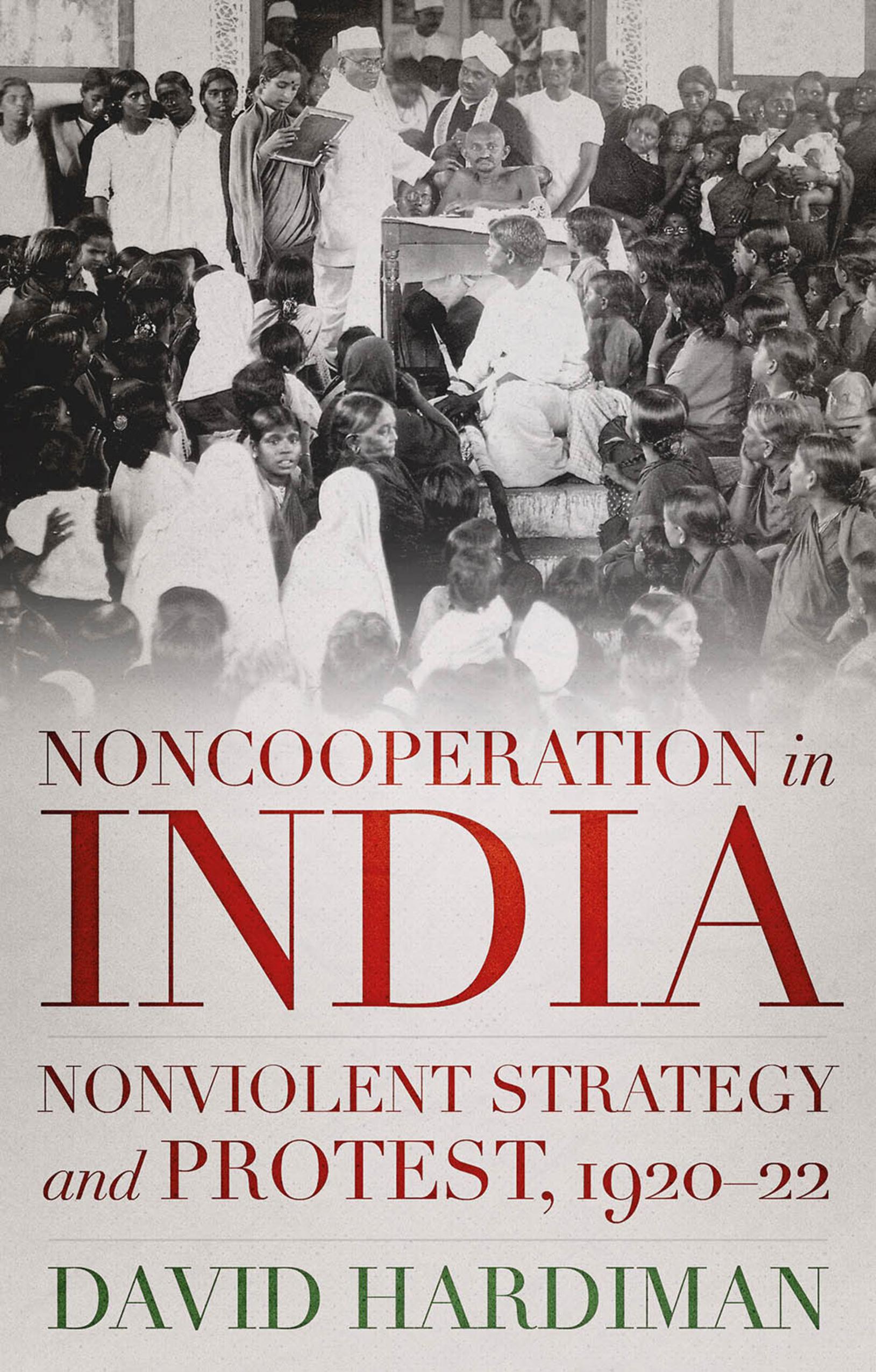

Copyright © David Hardiman, 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN: 9780197548301

Printed in India

GLOSSARY

Acara Transgression of an essential caste duty.

Adi-Dravida Untouchable communities of Tamilnadu, particularly of the Paraiyar group.

Adivasi Indigenous people considered to be ‘tribal’ by the British, being now classed as ‘scheduled tribes’ by the modern Indian state.

Ahimsa Nonviolence.

Akhada Gymnasium.

Amla Rent collector.

Asahyog andolan The Noncooperation Movement.

Avatar A reincarnation of a deity in bodily form on earth.

Baba Elder; learned or saintly person.

Babu Or iginally a title of respect used in Bengal, but later applied pejoratively for an anglicised elite.

Baniya Merc hant caste.

Begar Cor vée labour.

Bhadralok The ‘respectable people’ of Bengal, comprising the three upper Hindu castes of Brahman, Baidya and Kayashta.

Bhagat Devotee.

Bhagchasi Sharecropper, generally living in great poverty, in Bengal.

GLOSSARY

Bhajan Devotional song, hymn.

Bhakti Devotion to the divine.

Bharat India.

Bharat Mata Mother India.

Bhil Adivasi community of western India.

Brahman The highest, or priestly, caste among Hindus.

Burqa Voluminous garment that envelops the body and the face, as worn by some Muslim women.

Chamar Untouc hable caste, chiefly of leather workers.

Charkha Spinning wheel.

Chaukidar Village watchman.

Dacoit Bandit.

Dada Respectful address to an older man, an elder brother, paternal grandfather, or pejoratively a bully, lout, neighbourhood boss, or gangster.

Dharma Moral duty, law; more broadly, religion.

Dharmaraj The r ule of dharma.

Dharmic Religious duty.

Darshan Auspicious viewing that brings blessings on the observer.

Dhobi Caste that specialises in washing clothes.

Draupadi Wife of the five Pandava brothers in the Mahabharata.

Duryodhana Major figure in the Mahabharata – the eldest of the Kauravas and the chief opponent to the heroes of the epic, the Pandavas.

Eka / Eki Unity League.

Fakir Relig ious ascetic who lives on alms, normally Muslim.

Fatwa Opinion on a point of Islamic law given by a recognised expert.

Girasia Poor cultivating community of southern Rajasthan.

GLOSSARY

Gurdwara Sikh temple.

Haat Weekly market.

Hartal Form of protest involving a collective refusal to work or carry on trade for an agreed period.

Hijrat Mig ration, including mass migration as an act of protest.

Ho Adivasi community of eastern India.

Jagir Landed estate.

Jagirdar Holder of a jagir estate.

Jaikar Exhor tation of ‘Long Live!’

Jat Landholding caste of nor th-western India.

Jatha Band of militant Sikhs.

Jihad A str uggle or striving for Islamic principles that may involve an outward fight against those seen as the enemies of Islam, or as an inward struggle for spiritual perfection.

Jotedar Tenant with security of holding in Bengal.

Ka‘aba Holiest shr ine of Islam in Mecca.

Kamma Dominant peasant caste of Andhra.

karmi Worker.

Khadi Handspun and handwoven cloth.

Khatri Middle-status caste of traders, mainly of Punjab.

Khilafat Movement to save the Islamic Caliphate, a position that was held to be occupied by the Ottoman Sultan.

Ki jai! Exhor tation of ‘Long Live!’, preceded by an appropriate name.

Kirpan Short sword or knife with a curved blade, worn as one of the five distinguishing signs of the Sikh Khalsa.

Kirtan Devotional hymn.

Koeri Cultivating caste of United Provinces.

Kshatriya Caste of warriors and rulers.

Kurmi Cultivating caste of northern India.

GLOSSARY

Lathi Long stic k with metal cap.

Lingayat Dominant peasant caste of Kar nataka.

Mahabharata Great Hindu epic composed between 3rd C. BCE and 3rd C. CE. that narrates the struggle between the Kauravas and Pan . d . avas.

Mahant Pr iest in charge at a temple or monastery.

Mahisya Peasant caste of West Bengal.

Mantra Word or sound repeated to aid concentration in meditation; statement or slogan repeated frequently.

Maratha-Kunbi Dominant peasant caste of Maharashtra.

Maro! Cry of ‘beat!’.

Marwari Hindu or Jain merchants of the Baniya caste originating in Marwar region of Rajasthan, but found all over India in modern times

Maulana Revered Islamic scholar.

Maya Illusion.

Merua Derogatory Bengali term for a Hindi-speaker.

Muhajirin Religious migrants (Islamic).

Mullah Muslim sc holar, teacher and leader of a mosque.

Murti Image of a deity.

Mussalman Term for Muslim often used in Central and South Asia.

Oraon Adivasi community of eastern India.

Panchayat Assembly of elders or representatives of village, town, caste or community, a popular council.

Pasi Cultivating caste of the United Provinces, considered untouchable.

Patidar Caste of respectable cultivators in Gujarat.

Pir Islamic saint or holy person.

Prabhat pheri Pre-dawn procession in which religious hymns were sung, and nationalist songs.

Praja Subjects.

GLOSSARY

Qawwali Form of Sufi Islamic devotional music – widely popular in South Asia.

Raja King.

Rajput Caste associated with rulers and warriors.

Rakshasa Demon.

Rama Legendary ruler of Ayodya, considered the seventh avatar of the deity Vishnu. His adventures are recounted in the Ramayana (5th C. BCE)

Ramcharitamanas The story of Ram as recounted in the Awadhi dialect by Tulsidas in the sixteenth-century.

Ramraj The rule of Rama; thus a righteous form of rule.

Ravan The king of Lanka and the demon-figure of the Ramayana.

Ravanraj The r ule of Ravan; thus, a demonic form of rule.

Reddy Dominant peasant caste of Andhra.

Sabha An organised g roup such as an assembly, council, society, or association.

Sadhu Holy man who has renounced worldly life. Sadvi is the female form.

Salaam Gesture of greeting or respect typically consisting of a bow of the head and body with the hand or fingers touching the forehead.

Samiti Association.

Sant Saintly person.

Santal Adivasi community of eastern India.

Sanyasi Person who renounces material desire and prejudice, and who lives in a peaceful, loveinspired, simple, and spiritual way.

Sardar Chief, headman, or leader; jobber in Bengal.

Satya Truth.

Satyagraha ‘Truth-force’; a method of conflict-resolution advocated by M.K. Gandhi – most typically involving nonviolent resistance.

GLOSSARY

Satyagrahi Person who engages in satyagraha.

Seva Service.

Sevak Ser vant.

Shakti Divine power.

Shanti Peace.

Sharia Islamic law.

Shuddha Pure.

Sita Wife of Rama.

Swadeshi Self-help, self-production; a process of opting out of the imperial system and establishing parallel national economic and political structures.

Swami Hindu ascetic, holyman.

Swaraj Self-r ule, freedom, liberation.

Taluqdar Landlord.

Tapas/tapasya Voluntary acceptance of bodily pain to achieve a higher end, primarily spiritual realisation; selfdenial; penances.

Tehsil Sub-distr ict.

Thakur Deity, lord, chief, landlord, person of rank or position. In Gujarati and Mewari – thakor.

Ulama Islamic sc holars.

Ustad Honor ific of a highly skilled person, often a teacher or guru-figure.

Wahhabi Muslim reform movement that originated in the movement 18th century in Arabia under Muh . ammad ibn ʿAbd al-Wahha¯b that advocated a purification of Islamic practices, returning to the supposed fundamentals of the faith.

Zamindar Landlord

INTRODUCTION

The Noncooperation Movement of 1920–22 that forms the subject of this book was directed against multiple aspects of British imperial rule in India. It was one of the major mass movements of modern times. Supported by people from every level of the social hierarchy, it united Hindus and Muslims in a way that was never again achieved during the Indian national struggle. It managed to hollow out British rule, shaking its authority to the core. In general, it was remarkably nonviolent.

In my previous volume,1 I examined how nonviolent forms of resistance to imperialism were pursued under the rubric of ‘passive resistance’ during the first decade of the twentieth century. The technique was at the same time refined by M.K. Gandhi in South Africa in a campaign against the discriminatory treatment of Indians in that colony. Gandhi evolved a new practice that he called ‘satyagraha’, with a principled commitment to nonviolence at its heart. After his return to India in 1915, he campaigned to make such nonviolence a central commitment of the Indian National Congress, winning support for the idea through a small number of well-publicised local-level campaigns that he led successfully. Following from this, Gandhi launched his first all-India campaign in 1919 – the Rowlatt Satyagraha. The brutal repression of this protest in Punjab province created a ‘backfire’ against imperial rule, with mass alienation and a new vehemence injected into the nationalist movement. It paved the way for the campaign of 1920–22 that is the subject of this volume.

Hindu-Muslim unity was a crucial element in this movement, and we shall see how this came about in the first chapter. The second

chapter examines how the campaign was conducted, with tensions always being there between the Gandhian ideal of ethical nonviolence and a more expedient or pragmatic approach, that tolerated a degree of violence and that anticipated an escalation towards violent resistance once the conditions were ripe (which was clearly not the case in the early 1920s).Whereas Gandhi conceived this as a movement to provide above all a moral regeneration of Indian society, the pragmatists saw their task as winning political independence by any means possible. Over the next three chapters we go on to describe and analyse the many local manifestations of the movement. These campaigns were against not only British imperial officials, but also British businessmen – such as industrial capitalists and factory managers, indigo planters and tea garden operators – and also against Indians who were closely allied to British rule, such as landlords and Sikh temple priests. These chapters will bring out how a range of different classes and communities from all walks of life participated in the movement. We shall try to judge how nonviolent these disparate groups were in practice. All recorded cases of violence will be noted scrupulously, and attempts made to put them in context. In this, it should be remembered that historians have relied on government reports and newspapers for much of their information. The authorities had a vested interest in emphasising a supposed ‘violence of the masses’ so that they could argue that the nationalist leaders were mobilising such groups in an irresponsible way. Newspapers, for their part, tended to amplify any stray acts of violence for sensationalist purposes. Many historians have gone along with these reports, holding that the masses had a tendency towards violence. I shall try to be more discriminating in my use of such source material.

Chapter 6 examines how these disparate protests gelled together under nationalist leadership. This is described as a process of ‘braiding’ and involved several elements. First, there was a shared challenge to the authority of the British, who had assumed a God-given right to rule that had hitherto been largely accepted. The first section will see how this encounter played out in practice. We shall then go on to see how the nationalist message was propagated, before looking at the leadership of the movement at three main levels – the national, the provincial, and the local. Chapter 7 examines the structures of popular

nonviolence during what was known popularly as ‘asahyog andolan’ (the Noncooperation Movement). We shall see how solidarities were forged, the main forms of protest that were deployed, the way that popular campaigns to reform and purify the lifestyles of the masses fed into the protest, and the importance of beliefs that supernatural forces had blessed Gandhi, and the Congress and Khilafat causes. There is a discussion of how historians should analyse the common assumption of that time that supernatural forces were playing an active role in the protest; in other words, had historical agency. The chapter concludes with some observations on the forms that popular nonviolence took at this time. Was such protest peculiar to India, or are there parallels with subsequent nonviolent campaigns in other parts of the world? Was this – perhaps – a force that emanated from deep within Indian society, or – rather – was this a political strategy that emerged from wider, more global processes of modernity? The conclusion starts by examining the reactions of different Congress and Khilafat leaders to Gandhi’s decision to call off civil disobedience in February 1922 and goes on to evaluate the legacy of the Noncooperation Movement. Some observations are then made on the subsequent history of the Indian freedom struggle, and how independence was gained in 1947.

As in the previous volume, I shall be using the literature on nonviolent resistance to illuminate Indian history in a fresh way. Also, I shall seek to provide an intervention within it, raising questions about how the Noncooperation Movement fits its theoretical models. I shall also query the way that religious belief is handled within this field of study in the section in Chapter 7 on ‘enchanted resistance’. The book ends by revaluating some of the findings of the Subaltern Studies project in the light of nonviolent theory.

1 KHILAFAT

In recent years, militant Islam has gained a reputation for great violence. It was not always like that, as the history of the Indian Khilafat Movement reveals. In this, a movement that asserted a pan-Islamic identity opted to use nonviolent strategies in pursuit of its agenda. In doing so, it was able to make common cause with the Indian nationalist movement that was led by Gandhi. In this chapter, we shall examine how this came about.

The Muslims who led the Khilafat Movement rejected the style of politics of the All-India Muslim League, founded in 1906. The initiative for the League had been taken by people associated with the Mahommedan Anglo-Oriental College started in Aligarh in 1875. This had sought to provide western-style education for a Muslim elite that might then serve in the bureaucracy or professions then dominated by Hindus. The League, which was based in Aligarh, petitioned for reserved seats and separate electorates for Muslims in the constitutional reforms of 1909. They also demanded a fixed proportion of Muslims for appointments in government service and local government bodies. The League was dominated by rich and respectable men who proclaimed their loyalty to the British. By 1910, however, a younger and more radical generation of Muslims were emerging from Aligarh who sought to challenge the old guard. They argued that although the 1909 Act had granted separate electorates, such lobbying had failed to

prevent the reversal of the partition of Bengal in 1911 that went against the interest of Bengali Muslims. Also, in 1912, the British rejected the demand that Aligarh become a full university, which was taken as a snub to Muslim opinion. The young leaders saw that the Swadeshi agitation in Bengal had brought real gains – notably the reversal of the partition of Bengal – and felt that a more militant stance would benefit Muslims too.

Parallel with this, a new religious leadership was emerging that had been trained in reformed seminaries such as the one started in 1867 at Deoband in northern UP. Changes were made in these seminaries along the lines of English educational institutions, including a progression of classes, required attendance, examinations, and the granting of a degree at the end of a full course. They sought to build a cadre of ulama (Islamic scholars) who might spread traditional education, fostering Islamic principles and enforcing Islamic law – the sharia. In the early years of the twentieth century the predominant theology at Deoband became a more militant one, endorsing some fundamentalist Wahhabi doctrines. They did not however accept that the rule of the infidel should be opposed with violence, and there was openness to joining with Hindu nationalists to fight the British. Although the Muslim revivalist movement demanded Islamic purity, it was also a very modern movement, deploying the printing press for publication of journals and religious texts in Urdu, and establishing fund-raising networks and educational institutions. It also embraced a pan-Islamic consciousness that was largely new to India. Initially it claimed to be apolitical, but there was a clear political potential in the idea of a unity of Muslims throughout India and the Muslim world in general. By the time of the First World War they also were becoming dissatisfied with the politics of loyalism that many leading Muslims had pursued till then.1

The most prominent of the new leaders were two brother, Shaukat Ali (b. 1873) and Muhammad Ali (b. 1878). Their forebears had served as elite administrators under the Muslim ruler of Rampur in western UP, and in this they had a similar background to Gandhi. Shaukat Ali earned his BA from Aligarh in 1894 and joined government service in UP as an opium agent. He financed the education of Muhammad in England after he graduated from Aligarh in 1896 with the aim of gaining entry to the Indian Civil Service. He was awarded a BA in History at

Oxford in 1902 but failed the ICS exam, and returned to India. Like Aurobindo Ghose, he took a post in Baroda State. From there, he kept in close touch with Aligarh and its affairs. He was an eloquent speaker and writer and popular among the Aligarh students and alumni. He believed that Muslims should campaign with Hindus in the national cause rather than allow themselves to be divided by the British. He left Baroda service in 1910, becoming a journalist and full-time politician. The brothers were involved in the campaign for Aligarh to be granted university status in 1910–11. Muhammad started an English weekly published in Calcutta called Comrade to campaign on this issue. The British rejected this demand in a ruling of 1912. The two brothers became active also in pan-Islamic affairs. They raised funds during the Tripolitan and Balkan Wars of 1911–12 for a Red Crescent Medical Mission to Turkey to help those wounded. Aligarh students helped in fundraising, and some students even went to Turkey in 1912 to help with medical relief. A photo of Muhammad Ali at this time shows him dressed in the military uniform of this mission, wearing a Turkish-style fez and with a pointed and waxed military-style moustache. Although the British were neutral during these wars, Indian Muslims wanted them to intervene in support of Turkey. Now, however, Britain and Russia were allies against the Ottomans. Muhammad Ali stated that as the British had previously been in the category of those who helped Islam, they could be loyal, but that this was no longer the case. In 1912, the year in which the government of India relocated from Calcutta to Delhi, the Comrade made the same move, and once in Delhi, Muhammad Ali started a new Urdu weekly called Hamdard. To increase circulation, he adopted a more strident tone in these weeklies. By 1913, they were attracting government attention and had to pay a stiff deposit as security. There was an emphasis on the world of Islam. With the declaration of war in August 1914 by Britain against the Ottoman Empire, many Indian Muslims came to believe that there was a plot by European Christian powers to dismember the Ottoman Empire – the last great Muslim power. They believed that Arabs were being stirred up for this end.2

The issue of the Islamic caliphate now came to the fore. The caliph was regarded as the spiritual and temporal leader of Sunni Muslims, responsible for the defence and expansion of divine justice on earth.

Exactly who the caliph was had been disputed over time. The Mughals had sought legitimacy in India by portraying themselves as caliphs, and rival Muslim rulers of the late Mughal period had asserted themselves by declaring their allegiance to a different caliph, the sultan of the Ottoman Empire. Tipu Sultan of Mysore sent an embassy to Turkey in 1785-90 in recognition of the sultan’s position in this respect. After 1857, the British had demolished, in Minault’s words, the ‘whole symbolic system of authority’ in India by ending the last remnants of Mughal rule. The Ottoman Sultan was left as the one remaining Sunni potentate who could be regarded as caliph. The Sultans themselves encouraged such pan-Islamic sentiment in India to bolster their position in European conflicts. They were under attack in the Balkans and feared the hostility of other European powers, claiming that this represented ‘Islam in danger’. As Minault argues: ‘The locus of the caliphate and the person of the caliph mattered little; it was the existence of the caliphate which was essential, as a symbol to which homage was rendered, as a banner for Muslim rulers to wave when threatened by conquest or internal dissention.’ The acceptance of the Ottoman Sultan in this position at a wider pan-Islamic level was thus a late-nineteenth century phenomenon. Imams began to read his name on Fridays in mosques in India. Many Indian Muslims now supported the Ottomans in their wars.3

The Indian ulama became alarmed from 1911 onwards about the fate of the Ottoman caliph and a supposed threat to the Islamic holy places in Arabia, and increasing numbers became politically engaged. One such figure was Abdul Bari, a maulana (revered Islamic scholar) who was associated with another modernising seminary, the Firangi Mahal in Lucknow. He was an avid supporter of Turkey and had visited Constantinople in 1910–11. He and his students collected money for Turkish relief from 1911. He became associated with the Ali brothers in this work. The Ali brothers accepted him as their religious teacher, read the Quran in Urdu under his guidance and were deeply moved by it. Bari campaigned to unite Muslims around the demand to save the holy places of Islam. The three founded an organisation, the Anjumane-Khuddam-e-Ka‘aba, in 1913 to campaign for the protection of the Ka‘aba and other holy places of Islam. They claimed that this was a nonpolitical organisation. They hoped to enrol as members ‘every Muslim

in India’ who would take an oath on joining to give as much help as they were able in the service of Allah. Another activist who became involved in this work was Dr. Mukhtar Ahmad Ansari, who had trained as a doctor in Britain, and practised western medicine in Delhi. The Anjuman was based in Delhi with major branches in Lucknow, Bombay and Hyderabad (Deccan), and smaller branches in UP and Punjab. The leaders toured and held meetings, raising funds. The mother and wives of the Ali brothers and wife of Ansari held separate women’s meetings. Members wore crescent badges, and the Ali brothers now dressed in flowing green robes that symbolised their Islamic identity. Many important ulama and Sufis became members and there was much enthusiasm. Plans were discussed to fund military equipment for Turkey – a clearly political objective. Poor Muslims were financed for the hajj. Bookkeeping was however poor, leading to accusations of improper use of the funds. This discredited the organisation. The body was suspended during the First World War, as the conflict with Turkey prevented the continuation of its work. The body had however provided a template for future cooperative work between the ulama and western-educated Muslims. It used religious symbols, such as the Ka‘aba, the caliph, the green robes and banners. It reached out to Muslim women. It helped bring the ulama into politics and made many anti-British.4

Abul Kalam Azad of Calcutta was another significant leader. With a precocious intellect, he was a prolific writer, a talented Urdu stylist in both prose and poetry, and a persuasive orator. He was born in Mecca in 1888. His father was a respected Sufi of the Qadari and Naqshbandi orders who had migrated to Arabia, and his mother was an Arab. The family returned to India in the 1890s and settled in Calcutta. He was educated by his father, but after reading the writings of Syed Ahmad Khan saw that his traditional education was limited. He became highly critical of the existing ulama, who he saw as compromising religion for worldly gain. He became an erudite scholar who looked to the Quran to guide him in all aspects of life. He was impressed by the nationalist movement in Bengal in its Swadeshi phase and was enthused by the radicalism of groups such Jugantar and Anushilan. In 1908, he travelled through West Asia and met nationalists who were fighting Western imperialism in Iraq, Turkey and Egypt. He was inspired by their vision

of a battle for the integrity of Islam waged out of necessity by different Muslim nationalities but united by a belief in Islamic universalism under an overall loyalty to the Ottoman caliph. He studied the Quranic concept of jihad closely and argued that each Muslim nation should wage its own jihad against western imperialism. In India, this meant uniting with Hindu nationalists. Muslims should not however follow Hindu nationalists blindly but be prepared to take the lead in the nationalist movement despite their comparative lack of strength in numbers. They could remedy their minority status through strong selfassertion and become equal partners in the nationalist project.

Azad made a living during this period as a journalist, initially with the influential Urdu paper The Vakil of Amritsar, and then as editor of Al-Hilal (The Crescent), which he started in Calcutta in 1912. He and other contributors deployed Urdu poetry to powerful emotional effect. He propounded his views on jihad as anti-imperial struggle, with extensive quotations from the Quran. He also wrote about history and events in Turkey and western Asia and extolled Muslims who were resisting European aggression in Tripoli and the Balkans. He began to feel that the Aligarh movement overemphasised rationality, when religion was above all a matter of the heart. In this, there was a strong element of Sufi mysticism in his thinking. While on the one hand he criticised the ulama for their narrow-mindedness, obscurantism and factionalism, on the other he chastised westernised Muslims for their imitation of all things European and the Muslim League for its loyalism. He saw however that a new leadership was emerging from Aligarh more in tune with his beliefs and reached out to men like the Ali brothers. The government forced Al-Hilal to close in November 1914 due to its strident pro-Ottoman sentiments. A year later, Azad started another paper al-Balagh, but this also had to shut down when in 1916 he was interned in Ranchi, where he remained until January 1920. While so confined, he worked on a translation of the Quran into Urdu.5

In 1913 there was an incident in Kanpur that was taken up by Muhammad Ali. The Kanpur Municipality had demolished the washing place of a mosque to make way for a new road in a congested part of the city and was accused of desecrating a holy place. The ulama of Kanpur issued a fatwa demanding its restoration. The lieutenantgovernor of UP, Sir James Meston, dismissed the complaint, arguing

that Muslims had entered the washing place with their shoes on so that it was hardly a sacred spot. Nonetheless, he agreed to go to Kanpur to hear the complaints. There was a mass demonstration of Muslims on 3 August attended by an estimated ten-to-fifteen thousand. They carried black banners as a sign of mourning. There was a passionate speech by a local maulana who depicted this as a threat to Islam and who exhorted them to be prepared to sacrifice their lives if necessary. The crowd then marched to the mosque and attacked the policemen on guard there, throwing bricks. The police fired, killing several demonstrators, while others were arrested. The dispute now became a national one for Muslims, with Muhammad Ali, A.K. Azad and Abdul Bari becoming involved. Appeals were made in their papers for funds for the bereaved families of Kanpur. Even otherwise loyalist Muslim Leaguers joined the protest. The Viceroy, Lord Hardinge, was asked to intervene. Muslim opinion was virtually unanimous on the issue. Hardinge, who felt that the UP authorities had blundered, went to Kanpur himself, and overrode Meston. Charges against the prisoners were dropped and the demolished area was restored. Shaukat Ali wrote to his brother on how Muslim unity had achieved remarkable results, revealing the potential for future Muslim political campaigns.6

At the start of the First World War, the British made a point of emphasising that they were not engaged in an attack on Islam, only on the Ottoman government. They promised that the Muslim holy places would be protected, and that there would be no interference with the hajj pilgrimage. Many Indian ulama gave their public support to Britain on this. The government believed that the Ali brothers were pro-Turkey at heart, and they forced their paper Comrade to close by forfeiting its security deposit. The brothers were then interned under the Defence of India Act in Chhindwara in a remote part of central India. As the war progressed, it became clear that the European powers were aiming to displace the Ottomans from west Asia and then dominate it themselves. Lloyd George declared the British entry into Jerusalem in December 1917 as ‘the last and most triumphant of the crusades’. The Balfour Declaration of 1917, which promised a home for Jews in Palestine, revealed British support for the settlement of European Jews in a predominantly Muslim region. Radical Muslims in India began to feel that British promises of treating Islam fairly were a sham.7

Interned in Chhindwara, the Ali brothers studied the Quran and other religious texts in Urdu. Muhammad Ali was enthused by his reading. The brothers fully supported the Congress-League Pact, and although praising the moderate and secular Muslim leader Muhammad Ali Jinnah for achieving this, they pointed out that he was very aloof from the masses. They were also impressed by Gandhi, who had stated in a speech in Calcutta in 1915: ‘Politics cannot be divorced from religion’. They saw him as a Hindu leader who might be sympathetic to Muslims and corresponded with him. They were shocked at the Arab revolt against the Ottomans, seeing it as an attack on the caliph that was encouraged by the British. They failed to appreciate that this might also be a form of nationalism against imperial oppression. They needed the figure of the caliph as a symbol that united the brotherhood of Indian Muslims. In 1917, Jinnah and the Muslim League supported Annie Besant’s Home Rule League agitation. Besant demanded the release of Muslims interned during the war. Jinnah overcame his former distaste for mass politics and became president of the Bombay Home Rule League. The Muslim League elected Muhammad Ali as their president for the 1917 meeting when he was still interned, and at the session in Calcutta the president’s chair was left empty except for his photo. His mother, Bi Amman, spoke in his place, giving an impassioned speech while wearing a burqa, which was perhaps the first time a Muslim woman had addressed such a large political gathering in India.8

The Muslim radicals now sought Gandhi’s support for their cause and arranged a meeting between him, Abdul Bari and Ansari in March 1918. He was sympathetic to their argument that the Khilafat issue was a heartfelt grievance that united Indian Muslims. He agreed to campaign for the release of the Ali brothers and contacted the Viceroy to this effect. He was thus recognising the Ali brothers, Ansari and Abdul Bari as legitimate leaders of the Muslims of India.9 Like many other non-Muslim nationalists at that time, Gandhi accepted the claims of the ulama with their scholarly quotations in Arabic, and was hardly aware that the notion that the Ottoman Sultans were caliphs only became widely accepted amongst Indian Muslims in the late nineteenth century.10 He was not however concerned about the legitimacy of the claim, only that it was something that many Muslims felt strongly about and which he – as a champion of Hindu-Muslim unity – had a

moral duty to support. Faisal Devji has written of how in taking up the issue, Gandhi was asserting what he understood as a defining principle of Indian civilisation namely the give-and-take between Hindus and Muslims in India that had underpinned their relations for centuries. Both saw it as a religious obligation (dharma or farz) to respect the beliefs and practices of those of the other faith. By upholding the demand of the Khilafatists, Gandhi hoped to restore what he saw as an earlier empathy between the two religious communities – one that had been put under strain in the preceding years by the emergence of communalist political divides.11 In this, he sought to create a national polity that was bound together not by congruent ‘interests’, but by a sense of ‘friendship’, in which each group respected the beliefs, and even prejudices, of their fellow-citizens for the good of the wider whole.12

The annual session of the Muslim League was held in Delhi in December 1918, with Ansari as chair of the reception committee. He invited Abdul Bari and other ulama, who appeared for the first time at a League session. They demanded that the government represent the sanctity of the Muslim holy places and that all armed forces be withdrawn from Arabia, Syria, Mesopotamia, and other holy areas of western Asia. Ansari denounced British policy towards the Turkish ruler in strong terms, and the speech was subsequently proscribed by the government. They also demanded that the interned Muslim leaders be freed. Although the position of moderate Muslims in the League was weakened by all of this, the Muslim radicals did not regard the League as an appropriate vehicle for the Khilafat demand. It was an elitist organisation with only 777 members in 1919 and with little influence over the government. The Muslim radicals decided to start their own independent organisation and launched a Khilafat Committee at a meeting of 15,000 Muslims in Bombay on 20 March 1919. The president was a wealthy Bombay merchant, Seth Chotani. Sunnis and Shias of the city were both involved in this, even though Shias did not recognise the caliph, as all were concerned about the fate of the holy places under European domination over western Asia.13 The Khilafat Committee then supported the protest against the Rowlatt Acts that followed immediately afterwards, which ensured a powerful inter-religious unity for the protest. However, while some Khilafat