https://ebookmass.com/product/narrow-fairways-getting-by-

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

New Zealand Landscape: Behind the Scene Williams

https://ebookmass.com/product/new-zealand-landscape-behind-the-scenewilliams/

ebookmass.com

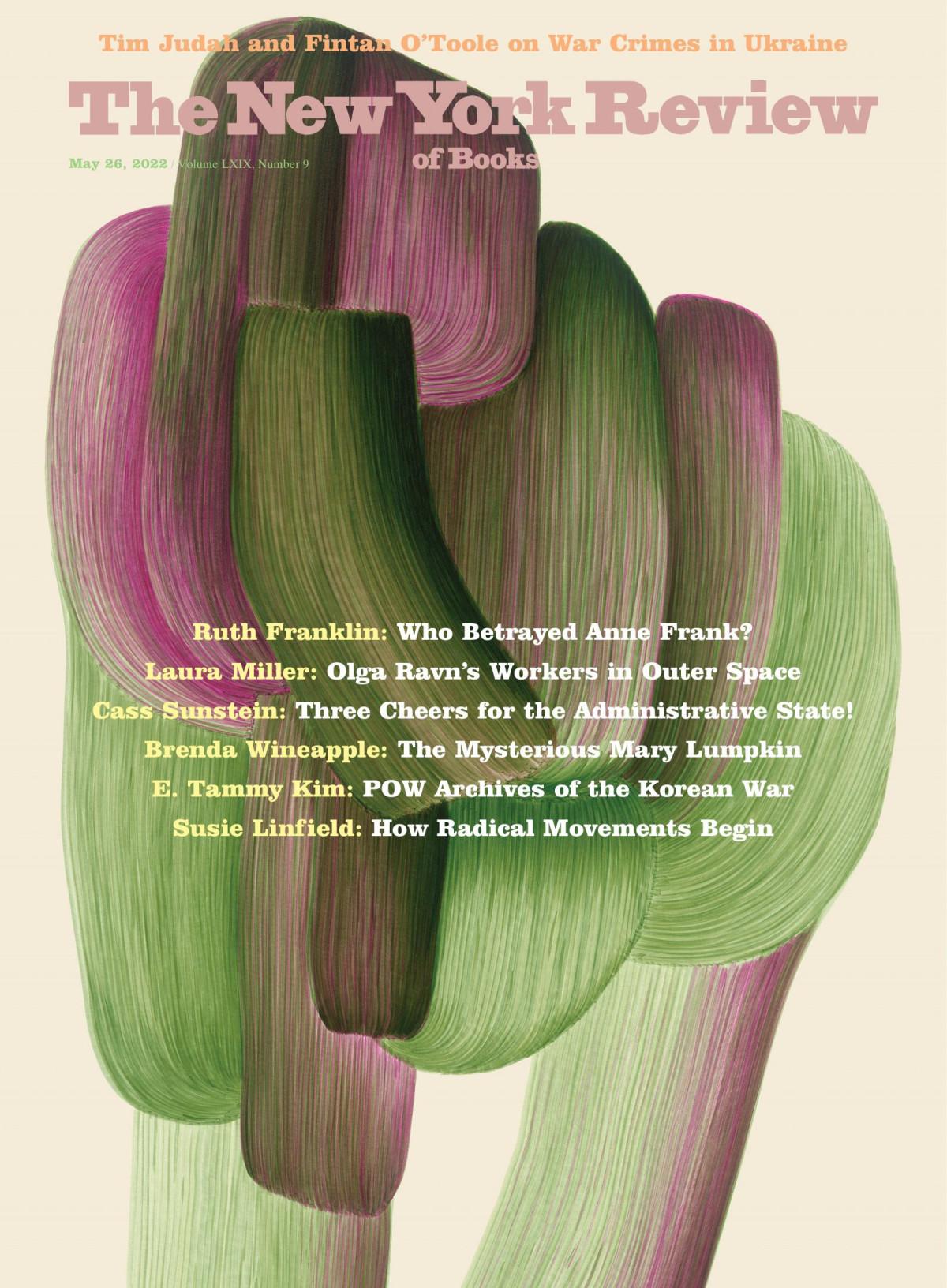

The New York Review of Books – N. 09, May 26 2022 Various Authors

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-new-york-review-ofbooks-n-09-may-26-2022-various-authors/

ebookmass.com

The New Cambridge History of India, Volume 1, Part 1: The Portuguese in India M. N. Pearson

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-new-cambridge-history-of-indiavolume-1-part-1-the-portuguese-in-india-m-n-pearson/

ebookmass.com

Atlas of Ultrasound-Guided Regional Anesthesia 3rd Edition

Andrew Gray

https://ebookmass.com/product/atlas-of-ultrasound-guided-regionalanesthesia-3rd-edition-andrew-gray/

ebookmass.com

Mirror of Nature, Mirror of Self: Models of Consciousness in S■■khya, Yoga, and Advaita Ved■nta Dimitry Shevchenko

https://ebookmass.com/product/mirror-of-nature-mirror-of-self-modelsof-consciousness-in-sa%e1%b9%83khya-yoga-and-advaita-vedanta-dimitryshevchenko/

ebookmass.com

Positive Psychology: The Scientific and Practical Explorations of Human Strengths 4th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/positive-psychology-the-scientific-andpractical-explorations-of-human-strengths-4th-edition-ebook-pdf/

ebookmass.com

Unlocking Small Business Ideas: An Australian Guide John W. English

https://ebookmass.com/product/unlocking-small-business-ideas-anaustralian-guide-john-w-english/

ebookmass.com

Metaphysics, Sophistry, and Illusion: Toward a Widespread Non-Factualism 1st Edition Mark Balaguer

https://ebookmass.com/product/metaphysics-sophistry-and-illusiontoward-a-widespread-non-factualism-1st-edition-mark-balaguer/

ebookmass.com

The Rise of English: Global Politics and the Power of Language Rosemary Salomone

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-rise-of-english-global-politics-andthe-power-of-language-rosemary-salomone/

ebookmass.com

https://ebookmass.com/product/biography-of-x-a-novel-catherine-lacey/

ebookmass.com

Dramatis Personae

Golf Caddies of Bangalore

Abdul experienced caddy in his fifties at the BGC who moved off Tannery Road, a neighborhood in the north of the city

Cherian wife

Mustafa oldest son

Fatima daughter

Irfan middle son

Rizwan youngest son

Anand thirty-three-year-old caddy at the BGC living at the back of a house owned by two uncles in the mixed-income community of Palace Guttahalli, north of the club

Aishwarya mother

Sushama wife

Padmini oldest daughter

Suri youngest daughter

Raja son

Arjun one-time caddy in his late-twenties living at the back of Challaghatta, a village highly stratified by caste located behind the KGA; also a professional golfer on the Professional Golf Tour of India and a parttime coach at the KGA

Kishori wife

Radhika oldest daughter

Anjali youngest daughter

Babu twenty-seven-year-old caddy at Eagleton, married with a child; father sold off land when he was younger, making his life a struggle

Divesh nineteen-year-old one-time caddy at Eagleton with a technical degree in engineering; part-time contract worker at Toyota; younger brother to Rishi

Ganesh thirty-one-year-old caddy at the KGA; ex-resident of a slum near the club who moved into a small two-story apartment complex nearby with the help of Akash, a club member

Sanjana wife

Asha daughter

Kumar son

Kannappa deceased brother; former professional golfer

Khalid caddy in his fifties at the BGC for forty years who struggles with alcohol abuse, and finds few partnerships with members and other caddies

Ayesha wife

Mahira oldest daughter

Harun son-in-law

Krishna caddy in his early thirties at the KGA; one of a handful of caddies organizing in the interest of caddy welfare

Rekha wife

Ashveer oldest son

Manikantan youngest son

Madhu caddy in his early twenties at Eagleton living in Banandur and preparing for a business career

Manju twenty-one-year-old caddy at Eagleton; temporary contract worker at local factories

Mohammed one-time caddy at the BGC in his mid-thirties and living on Tannery Road; coaches members at the Palace Grounds driving range; older brother to Rafiq

Prem thirty-six-year-old part-time caddy at Eagleton; local farmer in Banandur, where he lives; and aspiring full-time employee at Toyota

Rafiq—caddy at the BGC in his early-thirties living on Tannery Road; younger brother to Mohammed

Ravi thirty-one-year-old caddy at the BGC and former professional golfer living in Palace Guttahalli; working part-time as a golf coach at the Palace Grounds driving range

Lalitha—wife

Meghana—daughter

Rishi twenty-one-year-old caddy at Eagleton living in Banandur with dreams of facilitating big land deals in this part of the state

Sampath thirty-six-year-old caddy at the KGA living at the back of Challaghatta near Arjun; training to be a professional coach

Aditya mother

Sunil father

Basanti wife

Ramanna oldest son

Muniraj youngest son

Shashi caddy in his mid-twenties at Eagleton whose father sold land to Eagleton in the 1990s

Srikant twenty-year-old caddy at Eagleton, ostracized by extended family in Banandur

Thangaraj twenty-one-year-old caddy at Eagleton; close friends with Srikant

Selection of Club Members

Akash thirty-four-year-old club member and former professional golfer coaching at the KGA; instrumental in helping Ganesh and his family vacate a slum by the club and move into an apartment nearby

Ashutosh—club member in his forties at the KGA who offers his financial advisor’s services to Arjun as he begins to carve out an investment strategy

Chandra since-deceased club member at the BGC and among the founding club members at the KGA whose connections with a former state chief minister helped secure the land for a golf course

Chetan club member and administrative officer at Eagleton in his late thirties; part of the original family that founded the club

Dr. Kumal club member at the BGC, now deceased; retired diplomat who provided significant financial support to Abdul useful for educating his children; his son Kirin and his partner Luke later assume responsibility for Abdul’s son, Irfan, and help him move to the United States for school and work

Manoj—club member in his sixties at the BGC; instrumental in educating Abdul’s daughter, Fatima

Prakash mid-sixties club member at the BGC who joined with others to become a founding club member at the KGA in the 1970s; an important real estate mogul in the city

Sharif club member in his sixties at the BGC who hires Ravi to coach him

Vijay late-forties club member at all three clubs in the city; professional coach at Eagleton

Viswanth thirty-something-year-old club member at the BGC who facilitated Abdul’s move off Tannery Road, along with the help of his wife, Sunita

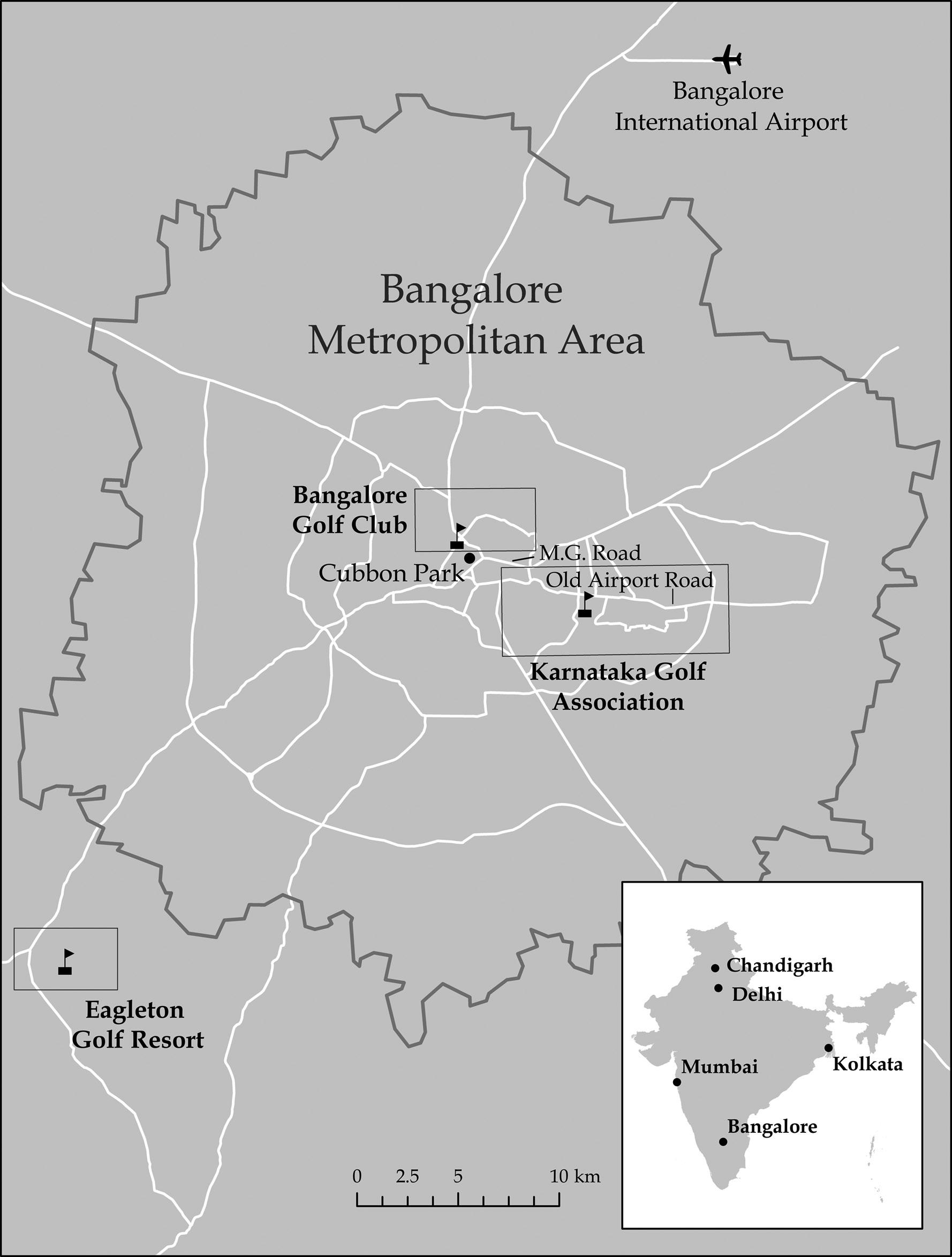

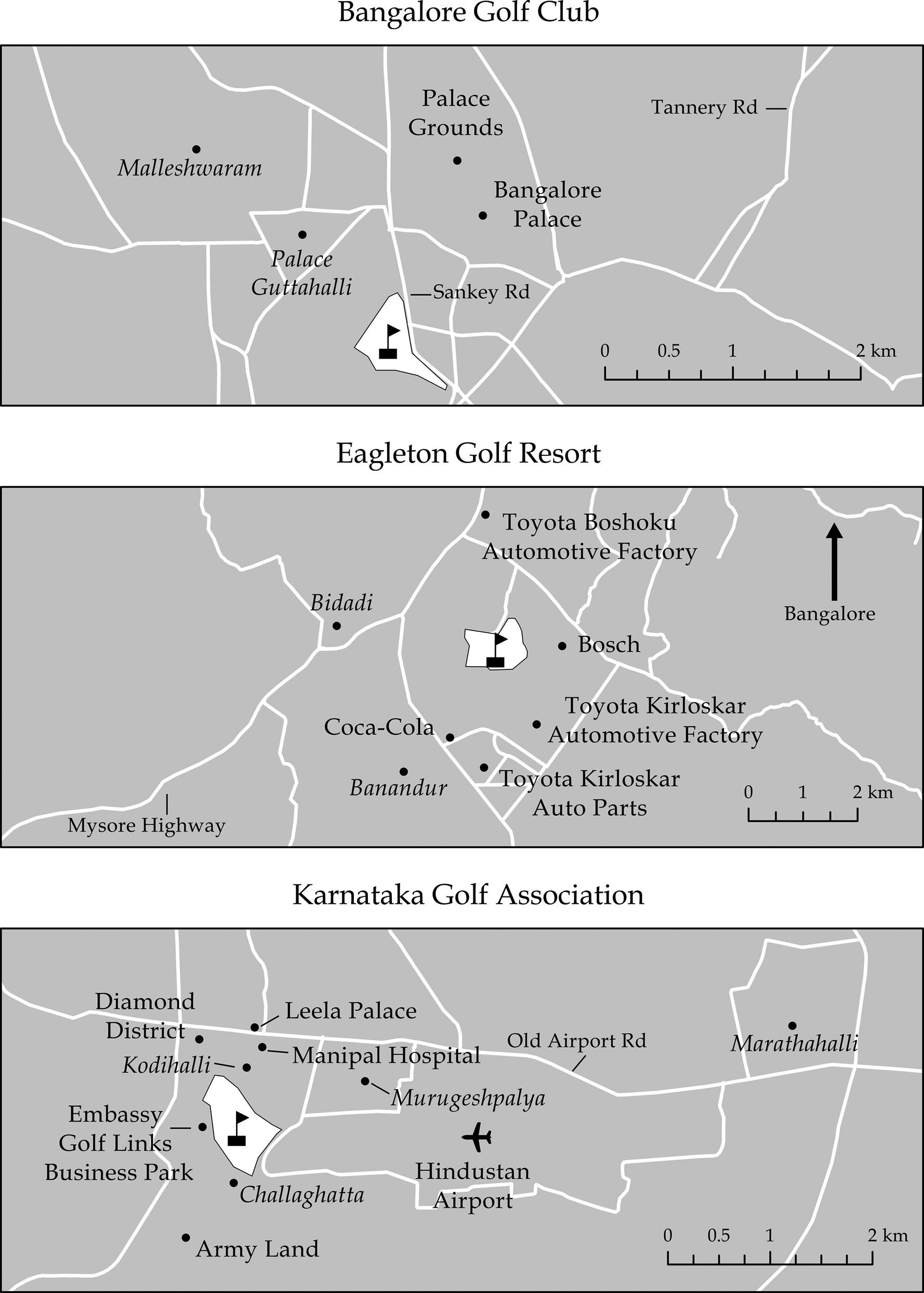

Map of City & Clubs

Narrow Fairways

Introduction

Krishna was four years old when his father Ramaswamy moved the family from their village in Tamil Nadu to Bangalore, in the neighboring state of Karnataka. Ramaswamy was a landless agricultural laborer, and when droughts parched the area in the 1980s, they dried up his livelihood, too.1 He had assumed, along with thousands of migrants from around the country, that there would be a great many opportunities in Bangalore, then fastemerging as India’s tech center and back office to the world. Unfortunately, all he could manage was a string of odd jobs—sweeping floors, cleaning toilets, and working construction sites. Broken and dispirited, he turned to the bottle, and, eventually, back to the village, without his wife and two sons. When, exactly, Krishna didn’t quite remember, but word came that his father had been murdered, falling victim to village goondas who had loaned him money he could never repay.

In the city, surviving family members lived in a shack cobbled together from plastic sheets, bricks, and plywood, east of what was then the international airport. Krishna attended a government school. By third grade, he was failing, and by fourth, regularly skipping classes. Encouraged by a neighbor, he showed up one morning at the gates to the Karnataka Golf Association (KGA), a new club looking for caddies. Upon his arrival, a caddy master summoned him, and soon he was paired with a member who handed him a tall bag containing some funny looking sticks curved at the bottom. He made only a few rupees that day, a small sum, but it impressed his mother, who sent him back the next day and the one after that, until it was all he ever did. When he was older, he tried other things. In his late teens, he borrowed money to start a canteen on the side of the road, but the business failed. In his twenties, he borrowed again to buy an auto rickshaw, the idea being to drive it between rounds of golf to make extra cash. The money was barely worth it. After a few months, he traded in the vehicle for cash, taking a loss. Caddy work was the only thing that stuck.

Shy of six feet, Krishna had a slight frame and an angular, unshaven face. At the KGA he wore a standard issue white bib with a red border, signaling

his “senior” caddy rank below professional but above junior and sub-junior. Though managed by caddy masters who worked on salary, he himself was not an employee—none of the caddies were. He earned what members paid him, based on a minimum board rate posted near the starters area. Including tips, he made 150–200 rupees a round, approximately $2–3 in U.S. currency.2 He never kept a budget, and family events such as birthdays and weddings, as well as emergencies, always left him short. It was like that with cash in hand—it came, it went, and when it did, he found himself calling on members to give him that little bit extra.

“They know my problems,” he said. “I can ask them for help. I’ll say, ‘Sir, I don’t have money to buy what I need.’ ” They were his bosses, or “gods,” as he referred to them. To win and keep their favor, he monitored their emotions, showered them with praise, bowed when he saw them, so that they knew he knew who was in charge. These performances of emotional labor, along with the physical requirement of carrying a thirty-five- to fiftypound bag around the course, helped, but only so much.3 He never made enough money to leave the job, only enough to have to come back to it, and he had, for twenty years and counting.

“My school is the KGA,” Krishna would say. By this, he meant not only the informal lessons in English he’d picked up over the years but others also—lessons in class, power, and respect, who got it, and why. “Big men like [Wipro CEO] Azim Premji come here to play,” he observed. “My boss doesn’t play with him as if he’s playing with the richest man in Asia. When they behave like that, why can’t I behave like that?”

It was different for people like him. He was poor and mostly powerless compared with members, given the working conditions within the club and the limited recourse he and other informal workers had in the society. Now and again he’d resist, but it was almost always as an individual. If asked to go on a round with a “bad” member, one who didn’t “pay the caddy” something extra and who gave little respect, sometimes he’d go along just for the board rate. Sometimes he’d steal fancy golf balls that cost as much as what some members paid him. Mostly, however, there was going along. He had mouths to feed, including his own.

“The members are like elephants,” as he put it. “When an elephant eats, food spills, and it’s eaten by thousands of ants. It’s the same for us. Members give out crumbs, and off that, we live.”

In January 2007, long before I decided to study Krishna and his peers and their working conditions, I arrived in Bangalore with only the most basic idea of what I wanted to understand about the place. Primarily, I was intrigued by the shape and composition of the city’s new middle- and uppermiddle-classes, who were influencing its economics and culture. At the time, India’s economy was humming along, the government having jettisoned rules and regulations that had hampered private industry since independence under what was derisively called the “License Raj.” The country was posting near double-digit growth rates. In the years since major economic reforms implemented in 1991 by then-finance minister Manmohan Singh, it seemed that everything was improving, with Bangalore and its wealthy elites heralded as leading catalysts.4

The most outspoken proponent of India’s growth story and the necessary role of an emerging entrepreneurial and salaried class was Thomas L. Friedman, op-ed writer for the New York Times, whose book The World Is Flat had just been published.5 It was on its way to being the most popular book on globalization to date, drawing praise and condemnation from across the political spectrum. For me, it offered a cue, and something of a guide to how to proceed with the research. On the opening page, Friedman told a story of standing at the first tee of the KGA with Infosys co-founder and CEO billionaire Nandan Nilekani. “Aim for IBM or Microsoft,” Nilekani advised as the two looked down the fairway at two glass-and-steel facades behind the first green. Friedman also noticed tee markers with Epson logos. His caddy was wearing a hat from 3M, too. Then, walking the back nine, he spotted offices of HP and Texas Instruments. “No,” Friedman wrote, “this definitely wasn’t Kansas. It didn’t even seem like India. Was this the New World, the Old World, or the Next World?” The sight of so many IT and tech companies had given Friedman hope, it seemed. Finally, India’s skilled and educated workforce would have the opportunity to compete on a more level playing field with their wealthier counterparts in developed countries. At home in Maryland, staring at the ceiling unable to sleep, Friedman nudged his wife. “Honey,” he whispered, “I think the world is flat.”6

Although short on empirical evidence and long on anecdote, many business writers and serious economists alike shared Friedman’s optimism, if not always his enthusiasm—all agreed that more, not less, globalization was the key to growth and poverty alleviation in India and elsewhere in the developing world.7 They joined Friedman in lauding entrepreneurs and investors like Nilekani who were now unshackled by government red tape,

and thus in a better position to leverage India’s comparative advantage in young, well-educated English speakers. Harvard economist Edward Glaeser even saw in Friedman’s catchphrase something truly visionary. In one of several unacknowledged references in his own bestseller Triumph of the City, Glaeser called outsourcing giant Infosys a “flat world phenomenon,” and Bangalore a “boom town.” In a conclusion titled “Flat World, Tall City,” Glaeser encouraged business leaders and local politicians in other developing world cities to take up the “Bangalore model.”8 If they could draw on their own cheap but skilled labor force and offer low or zero corporate tax rates to entice equally profitable businesses to set up shop, the rest, presumably, would take care of itself. The arrival of a flat, or flattening, world of good jobs and better opportunities was pitched as a sure thing.

I had only to walk the perimeter of the KGA to register some nagging doubts about the picture Friedman and others had painted. Two decades removed from India’s awakening and more than three since Bangalore was donned “India’s Silicon Valley,”9 members and guests played golf on lush fairways and remarkably green greens, even as poor and working-class people struggled to survive mere steps away. Opposite the tenth fairway behind a thick row of trees fronting an open sewer, hundreds of migrants lived in makeshift homes without toilets or clean water. Similar living conditions predominated south of the course in Challaghatta, adjacent to IBM and Microsoft. At the back of this village, lower-caste families sent their children to schools with underpaid and often absent teachers, while upper-caste families living in the center reaped a windfall selling farmland to corporations and, with the profits, extended advantages set down by history and tradition.

It was left to skeptical activists and scholars to point out the wild discrepancy between Friedman’s vision of Bangalore and these stark realities. “As of now,” geographer David Harvey wrote in a review of Friedman’s book, “only 2 percent of the Indian population of 1.2 billion (according to Friedman’s estimate) participates in the new prosperity epitomized by the view from the golf course.” The rest, he said, lived in “conditions either ‘unflat’ (full of pain and despair) or ‘half-flat’ (full of anxiety, hoping and struggling to find a place),” and Friedman’s policy prescriptions were why.10 Neil Smith similarly noted the way exclusive spaces like the KGA were the only “facts on the ground” that mattered to Friedman, even as low wages, threats to workers’ rights, and unsafe working conditions described life for much of India’s majority.11 Reducing his vision of the world to the “CEOs he knows,

and the golf courses he plays at,” environmental activist Vandana Shiva further argued, Friedman “shuts out the social and ecological externalities of economic globalization and free trade.” Protected by “walls of insecurity and hatred and fear,” Shiva continued, clubs like the KGA, and other exclusive sites visited by Friedman on his tour of India, mask the adverse effects of neoliberal policymaking.12

These and other critics perceived the KGA as a symbol of all that was wrong in cities like Bangalore, and, moreover, in Friedman’s analysis of it—Friedman, to be fair, clearly used the club as a rhetorical prop, and his metaphor of a “flat world” was never meant to be taken so literally.13 But I wondered if the KGA might also serve a more practical, analytical purpose. I had in mind a deep ethnography, where I could develop observations by actively participating in the life of the club, hanging out with members and guests, attending special events, and, yes, playing golf. I didn’t know any members, which was a hurdle, of course; worse, the sum of my golfing experience was a few lessons as a teenager, and a pair of year-end staff tournaments during my time as a high school teacher in Vancouver, Canada, where I was raised and educated. Nevertheless, I enlisted the help of an acquaintance from an earlier visit, a member at the Bangalore Golf Club (BGC). He recommended a caddy named Ravi, thirty-one years old at the time, who moonlighted as a coach, giving lessons at a driving range within the Palace Grounds, a mostly barren 400-acre area a couple miles north of the BGC owned by the former Maharaja of Mysore and his family. The range was a public space, ideal for my purposes. I could visit anytime I wanted and speak with whomever I wished.

I paid Ravi 150 rupees for one-hour lessons. We’d start at seven in the morning, three to four days a week, just as BGC and KGA members living on this side of town were showing up to practice. I met several of these members—mostly, if not all of them, men.14 In a matter of weeks, they invited me to the clubs for meals and drinks to hang out with them and their friends. Soon, I was visiting the clubs daily, eventually taking a sixmonth membership at the KGA, and playing at both clubs, thanks to an arrangement between the two;15 I later incorporated visits and rounds of golf at a third club, the Eagleton Golf Resort, south of the city. I sat with members on clubhouse patios, visited them in their offices and homes, and at bars and restaurants, but always in air-conditioned spaces tucked away behind secured fences and walls, far removed from the poverty of India.

If it wasn’t for Krishna, whom I hired as my caddy the first time I played at the KGA, I would likely have continued to study members in just this fashion, fielding their thoughts on the changes in the country while taking for granted that they lived in a world apart from the masses on the other side of the walls and fences they had built. When Krishna talked about the KGA as a school on the very first round I hired him, it didn’t so much change the study as bring it into sharper relief. I wanted to learn what he had learned in this space, and I reorganized my schedule and approach accordingly. Before and after rounds at the KGA, I hung out with him and his peers inside the caddy station where members and caddies were paired. I did the same at the BGC, with Ravi as my caddy, coach, and guide. I met with them and their friends outside the clubs, having a coffee or beer and grabbing a cheap meal at corner stores and canteens, often, though not always, accompanied by one of my two interpreters, Meera Kumar and Umesh Kumar (unrelated).16 I visited Krishna, Ravi, and a select few others in their homes and communities to share home-cooked meals. I walked their children to school, where I sat at the back of classes making observations, and then brought

Image I.1 The Palace Grounds driving range (2014).

them home safe. I also traveled with these caddies and their families to celebrate festivals or special occasions in their native villages, hopping on and off trains and buses on multiday journeys.

Splitting my time in these ways, meeting with members and caddies separately, and then observing the interactions between them on the golf courses, I was struck by the strength and utility of their economic and social bonds. Just as well, I was struck by how little either side in the debate on globalization had to say about such connections, but especially on the academic left. Certainly, inequality was on the rise, and with it, a decline in opportunity, not in spite of globalization, but because of it, a view reflected in recent studies.17 Yet the world, or Bangalore, wasn’t “divided” or “fragmented,” either, in the ways critical scholars and activists imagined— Mike Davis offers perhaps the most forceful presentation of this view, when he notes a “diminution of the intersections between the lives of the rich and poor.”18 This prevailing and largely unquestioned image of “two Indias” that still rules the discourse on globalization appeared to me equally as wrongheaded as the ideas that animated conservative texts heralding “business friendly” environments as the only way to grow an economy and alleviate poverty. As I became more and more committed to understanding the experiences of Krishna and other caddies working this social and economic divide, I sensed that an insistence on such “topographic representations,” in the words of Saskia Sassen,19 bore little resemblance to what actually transpired in the lives of India’s poor, and in the lives of these caddies, in particular. Advancing what Janice Perlman once called the “myth of marginality,”20 moreover, I believed that many otherwise critical scholars had also misjudged the very effects of globalization.

Rich and poor did not live separate lives, as if inhabiting “parallel universes.”21 Nor was it true that some real or metaphorical playing field was being leveled, erasing all differences between them. Rather, rich and poor were necessarily being drawn together as a result of globalization, and in ways that both upended yet reproduced a status quo long in the making.

At Independence in 1947, many expected India to follow a developmental path similar to that of the United States, Great Britain, and other industrialized societies in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, envisioned a large and mostly urban workforce collectively contributing to, as much as benefiting from, the gains of industrial development.22 Alongside politicians and journalists,