Acknowledgments

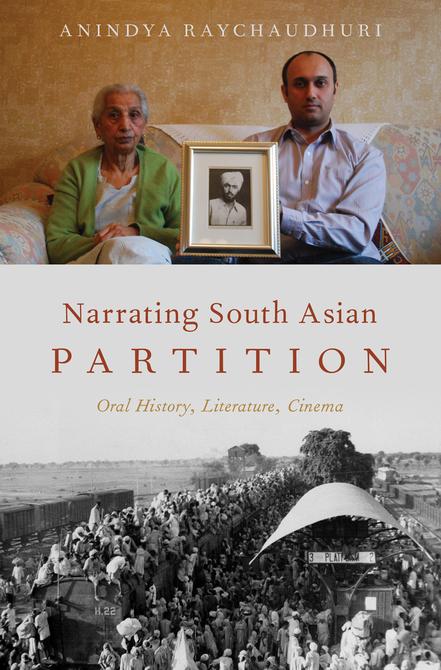

The first and greatest debt of gratitude I have is to all my interviewees. You gave me your time, your most precious stories; you welcomed me with warmth, food, and love. This book would not exist without you, and I hope that you feel I have done justice to your stories. All of you who are featured in this book, and the many of you who spoke to me but whom I could not find space for in these pages—I thank you. I cannot put into words how much your kindness has meant to me. A few people have passed away before this book saw the light of day, and I hope I have managed to honor their memory in these pages.

The second, and just as great a debt of gratitude is owed to the many, many people who helped me with their time—finding people I could interview, and then taking me along to their homes. Thanks to this research, and to the unbelievable generosity on the part of far too many to name, I was not only able to collect invaluable material, but I have also acquired good friends in Delhi, Karachi, Kolkata, Lahore, and all over the United Kingdom—many of whom were strangers when I started this work. People gave of their spare time unhesitatingly, and immediately in a way that was completely unexpected. None of you had to help me, none of you stood to gain anything from helping me, and I do not know how to repay your generosity.

This research started life as Migrant Memories, a project run by Butetown History & Arts Centre, and funded by the School of English, Communication, and Philosophy, Cardiff University. I am very grateful to everyone involved in both organizations. Subsequently, I was lucky enough to be awarded a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellowship, which allowed me to conduct interviews in the United Kingdom and in south Asia. I am very grateful to the funders for making this research possible.

Much of this book was written in libraries, and I am grateful to the staff of Cardiff University library, University College London library, University of St Andrews library, Edinburgh University library, the British Library, and the National Library of Scotland.

I am very grateful to Nancy Toff and the many wonderful people at Oxford University Press. Rob Perks first mooted the idea of this book, and it certainly would not have happened without his support.

While I can never individually name everyone who helped me along the way, there are some who I have worked with, and benefited immensely from, and whom I cannot ignore. In particular, I am grateful to:

In Cardiff: Radhika Mohanram, Rhys Tranter, Aidan Tynan, Chris Weedon, Jennifer Dawn Whitney.

In London: Juliette Atkinson, Kasia Boddy, Phil Horne, Pete Swaab, and everyone else in the Department of English, University College London.

In St Andrews: Christina Alt, Matthew Augustine, Lorna Burns, Alex Davis, Katie Garner, Clare Gill, Sam Haddow, Ben Hewitt, Tom Jones, Peter Mackay, Andrew Murphy, Katie Muth, Gill Plain, Neil Rhodes, Susan Sellers, Jane Stabler, and all the other wonderful people in the School of English. A special mention is due to Hannah Fitzpatrick and Akhila Yechury for their many comments, suggestions, in- car conversations, and general support.

In Kolkata and West Bengal: Supurna Banerjee, Souvik Mukherjee, and many others.

In LUMS, Lahore: Christine Habbard, Furrukh Khan, Nida Kirmani.

In Delhi: Maaz Bin Bilal, Seema Chisthi, Akshay Gururani.

Outside the world of universities, I am grateful to Butetown History & Arts Centre, Cardiff; Faith Matters, London; and Sikh Sanjog, Edinburgh for their help and support.

A number of people helped me to transcribe some of these interviews and I am grateful for this help: Holly Fathi, Khadeeja Khalid, Eve Lavine, Claudia Mak, and Aaminah Kulsum Patel.

Mrs. Bushra Asghar and family in Lahore, and Mr. Hirak Roychowdhury and family in Delhi put me up and looked after me during fieldwork, and I am very grateful.

I have presented aspects of this work in conferences at Royal Holloway London; LUMS, Lahore; Jadavpur University Kolkata; the University of Strathclyde; and the Crossroads conferences in Paris and Tampere, Finland, and I have benefited from the useful feedback I have received at all of these places.

Finally, and most important, Clare, and my parents— Ma and Baba—have lived through this project just as much as I have and, again, I only hope the results were worth the stress I have put them through.

Introduction

At some point in the late 1980s, in a small suburban town about thirty miles north of Kolkata, in what is today West Bengal, India, a woman was walking home with her young child. On the way home, their conversation turned to their family’s origins. The memory of this conversation is still surprisingly vivid for this woman, Sipra,1 almost twenty-five years later:

When my son was about six or seven years old, one day, the two of us were walking back along the road. Then the conversation turned to where I lived as a child, our—where my parents used to live. While talking about this, I said that Bangladesh was our real home, but when the country was divided, it is no longer possible to go there. He asked how it happened. Since he was really little, I told him that there was a time when it was decided, the leaders decided to divide up the country and make the two countries separate. After that, the two countries, in the two countries, Hindus and Muslims would go their separate ways— Muslims would stay in Pakistan, most of the Muslims would stay in Pakistan, and most of the Hindus would stay in India. And like this, it divided in two. Then he asked, “After they were divided, you can’t go from one country to another? You can’t go and live there?” I said, “No, you can’t.” He came to a stop in the middle of the road, I can still see it clearly— standing in the middle of the road, he said, “That means, one day someone can tell me, in Chandannagar [their home town] that you can’t come here anymore, can’t live here in anymore. How can that be?” I felt so bad hearing that. And I don’t know—afterwards, my son worked on partition, perhaps the seeds of that work were sown in his mind all those years ago.2

Now, there is nothing especially remarkable about this account. True, Sipra reveals in her testimony images or themes that are common across a number of different partition narratives but, apart from the fact that I have interviewed

a number of different members of this family as part of my research, there would normally be little reason to open my book with this narrative. The reason I start with Sipra’s story is primarily a selfish one— she is my mother and the little boy of the story is me. As detailed and vivid as Sipra’s memory of this conversation is, however, I have no memory of it myself. If there is a link, therefore, between that conversation then, and my decision to work on the partition now, it is certainly not a conscious or deliberate one.

But it is not as if the two are completely unrelated either.3 And my decision to start with this story is not merely self-indulgent because Sipra’s testimony highlights the complexity of the ways in which partition is remembered, talked about, narrated, or, indeed, not talked about or forgotten. The memorial legacy of partition is one of trauma, pain, and shared suffering, but it is also always productive, not in the sense of it being a positive event for the people who lived through it and its legacy but productive in the sense that it helps to produce narratives. These take the form of literature and cinema and visual art— stories which together create both memories and ways of dealing with memories. Partition also produces identities—religious, national, political, professional—partition changes how people think about themselves. Sipra’s voice breaks down as she remembers her son’s pain, and the pain that it caused her in turn. As I return to this testimony in the pages that follow, I show how Sipra charts a familial inheritance of loss and grief—from her grandmother’s laments at the loss of a home to her desire to see her father settled under his own roof to her young son’s discovery of the uncertainty of the migrant. Within her own narrative, she explicitly constructs a direct, causal relationship between her son’s feelings of confusion and uncertainty then and his decision to work on partition narratives now. Memories, no matter how painful or traumatic, become part of the life narrative that we construct for ourselves, and which becomes our identity. This book is concerned with both this memory of pain and trauma on the one hand and the productivity of partition on the other.

As for myself, while it is true that I have no memory of this incident, in many ways it is still where my partition story begins. Growing up in a refugee family, I would sometimes get bored with the way grandparents and greatuncles and aunts would repeatedly visit our ancestral home in their stories. As I grew older, and became a migrant in turn, choosing to leave India for the United Kingdom, my own attachment to and interest in my familial roots deepened, on both an emotional and an intellectual level. Like many scholars who have come before me, my interest in partition ultimately stems from my memories of these stories, some of which are represented in this book. Following pioneering partition scholar Urvashi Butalia, I, too, can say: “This story begins, as all stories inevitably do, with myself.”4 The original shock of discovery—the moment that I learned about the ultimate instability of home, the moment that caused me to stop in my tracks, according to my mother’s

narrative, may not have remained in my consciousness, but it has undeniably persisted in terms of its effects on my identity as doubly displaced and has made its presence felt in numerous ways, not least in my intellectual engagement with partition and what it has meant for so many families.

Historical Context

In 1947, as British rule over the Indian subcontinent came to an end, the land and its people were divided into two new states, broadly along religious lines. Kashmir and Punjab in the west and Bengal in the east were divided in two. West Punjab, along with Azaad Kashmir, Sindh, Baluchistan, North-West Frontier Province, and east Bengal, formed the new Muslim-majority state of Pakistan. This was a state of two halves, separated by hundreds of miles of India, which had a Hindu majority. In 1971, East and West Pakistan divided again, leading to the independence of Bangladesh.

The precise causes of this division are many and various. At various points, various academic and non- academic authorities have blamed, in turn, Britain’s “Divide- and- Rule” policy, the intransigence of Hindu nationalist leaders, the personal and communal ambitions of the leaders of the Muslim League, the militancy of the Sikh leadership, and treason and betrayal on the part of all of the above. What is certain is that, in time, partition came to be a seismic event that completely transformed public and private life all over the subcontinent. After partition, nothing would ever be the same again.

In part this significance comes from the unprecedented levels of violence, certainly in recent south Asian history, which accompanied the act of partition. Inevitably, perhaps, estimates of actual numbers of casualties remain controversial. The most conservative figure of the number of deaths was that suggested by the eyewitness account of British administrator Penderel Moon who, in 1961, wrote that he believed only about 200,000 people were killed in the Punjab.5 At the other end of the scale, Kavita Daiya is one of a number of south Asian scholars who has put the figure at “at least two million.”6 Most scholars, like Ian Talbot, believe that the number to be about 1,000,000—in short the exact number will probably be never known.7 What is generally accepted is that along with the death toll, the partition led to the largest forced migration in human history, with an estimated 18 million people forced to leave their homes forever.8 In addition between 100,0009 and 150,00010 women were abducted, raped, and often forced to convert religion.11 The emotional losses were also huge, as people had to leave ancestral homes— communities where they had been living since time immemorial. Most were unable to take any of their property with them; some deliberately chose to leave everything behind because they were convinced they could come back at a future date. Millions of people became destitute overnight. Returning home

proved impossible, as conflict between the two states intensified, leading to multiple wars since independence.

The legacy of partition has been similarly contested, controversial, and, at times, violent. The shockwaves have radiated outward through space and time—affecting both those who lived through the trauma, and those (like myself) who did not witness the events but carry with them stories of the horrors that ensued. Every aspect of life in the subcontinent—religious, regional, and political identities; community relationships; cinema, art, and literature—has been indelibly marked by the events of 1947. Partition is at once the least talked about and most cited event in south Asian history. From cricket matches to religious riots to nationalist speeches to phony and real wars—partition continues to be used to justify the actions and the self- construction of all the post-partition nation states.

Methodological Background

An overwhelmingly large majority of books on partition limit themselves to studying the way partition was experienced along the western border (east and west Punjab and Delhi). There are a smaller number of books that examine the legacies of the Bengal partition12 and the effects on “other” communities such as the Sindhis are even less well studied.13 There are, however, no booklength studies, especially in oral history, that attempt to include voices from all the communities affected by partition. This segregation may well arise from a laudable attempt at precise contextualized specificity, but the effect it has had is to create an artificial and anachronistic divide between the two halves of partition. As one of the first oral history and cultural studies accounts to include both Punjab and Bengal, this book will begin to correct this gap. This trend of small- scale studies has led to a perhaps unintended and artificial understanding of partition as being single- sited, involving two separate continuous borders that do not need to be studied in the same scholarly space. By examining the two partitions as being two components of one larger process, I hope to enhance the way we understand partition.

Second, for all the excellence of the scholarship, there is, to date, no full-length study of partition that examines oral history and cultural representation together. In the scholarship of partition, these domains remain segregated, and they are usually populated by academics of very different professional and disciplinary backgrounds. Far from being mutually exclusive, however, these domains are always already in direct conversation with each other. To understand how private memories and public representation work together, they must be studied together. Partition and its memories are both deeply intimate and glaringly public. What is the relationship between the private form of testimony, the oral history narrative, and the public form of cultural representation, literature, cinema, and visual art? How does one genre

influence another? What might be gained from studying these different types of memorial narratives together? From the very beginning, then, this book was conceived of as a way in which oral history testimonies could be compared with cultural representation.14

The idea that private, personal memories of war and conflict are shaped by “templates of war remembrance . . . [the] cultural narratives, myths and tropes . . . through which later conflicts are understood”15 is now well established, though the consequences of this argument have perhaps not been fully applied to partition scholarship. There is a complex dialectical relationship between the public representation and private memories of partition—how people’s memories are influenced by public discourse and how the creative and critical practice of academics, artists, and activists is influenced by their own direct and inherited memories. These lines of influence are not often direct or explicitly chartable, though they sometimes are, but more often they are nevertheless present in more diffuse forms. As Jill Ker Conway has put it, “our culture gives us an inner script by which we live our lives.”16

Studying oral history and cultural representation helps to emphasize the ways in which both of these types of narrative inhabit the present just as much as they describe the past. In other words, my interest is emphatically not to uncover any kind of objective truth about the history of partition, even assuming such a thing were to exist. I am not interested in whether or not the narratives under discussion here are historically accurate but in how they are put to work in various ways in the present. Mistakes, misrememberings, and inaccuracies can be just as interesting and just as valuable to understanding the legacies of partition.

The oral history material for this book is derived from 165 interviews, collected over three and a half years in India, Pakistan, and the United Kingdom, though I wasn’t able to include all the interviews here for reasons of space. I had to cancel two planned trips to Bangladesh at the last moment due to political violence, so unfortunately there are very few voices here from those who identify as Bangladeshi, although there are many who identify as east Bengali. This cohort represents a diverse group in terms of religion, age, gender, national, and class backgrounds, though, and following a long tradition of oral history, the cohort was never intended to be representative.17 The recruitment process for participants was extremely organic—a mixture of word- of-mouth and personal contacts, official and semi- official approaches to religious and community groups, as well as more formal contact with various academic and non-academic organizations. I have, wherever possible, attempted to make the cohort as diverse as possible but I have not set any selection criteria beyond a genuine desire on the part of the participant to be interviewed. As such, I would be very suspicious of drawing any conclusions about collective patterns of remembering based on these individual testimonies. As Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak has written, “There is no more dangerous pastime than

transposing proper names into common nouns, translating them, and using them as sociological evidence.”18

Most of the interviews were conducted on an individual basis, but occasionally it became necessary to conduct group interviews with multiple family members at the same time. Although such group interviews often do raise potentially troubling issues of power between the interviewees, it is also the case that the group dynamic allows for different themes or topics to emerge that might not in a more conventional one-to- one interview.19 This is especially the case in the south Asian context, where collective conversations are perhaps more naturalized a part of everyday life than in Europe or America. When I have had to conduct collective interviews, I have tried to recreate the atmosphere of an adda “the practice of friends getting together for long, informal, and unrigorous conversations,”20 in the words of Dipesh Chakrabarty. There is something peculiarly non-hierarchical in the institution of the adda which, when applied to the oral history interview, allows people to hold diametrically opposite views without necessarily challenging social hierarchies of gender, age, and class. At numerous times during many of my group interviews, my participants have loudly disagreed with each other, demonstrating the contested nature of memories in a direct way that would not necessarily have been possible in a one-to- one interview. This does not mean that my interviews are immune to such social hierarchies, but that these issues affect one- on- one interviews just as much; in any event, in most cases where I conducted group interviews, an individual, one- on- one interview was simply not an option.

Of course, oral history interviews never exist outside the practical contingencies of time and place. No interview is ever an ideal transmission of information between the interviewer and interviewee, and the location and physical context of an interview always has an effect on the nature of the testimony.21 At numerous points during my fieldwork, my interviews were adversely affected by issues such as equipment failure, sudden illnesses of an often elderly cohort of participants, excessive extraneous noise, and the presence of overly interfering family members, to name but a few. Listening to the recordings of the interviews, it is fascinating how often “real life” ends up intruding, reminding me that the interview is hardly a pristine space. Captured on my machine, along with the questions and answers that constitute the interview, are also other voices, other conversations, repeated exhortations to eat,22 traffic noises, and the ubiquitous fan. Some of these external influences inevitably hampered the interview, but, whenever faced with less than ideal circumstances, I always worked on the principle that an imperfect interview was better than no interview at all and always tried to work around whatever difficult scenario I was faced with.

During my interviews, I always tried to replicate, as much as possible, an environment that would be familiar for my participant. Thus I almost always

interviewed in the participant’s home or another place where they would feel comfortable. As most of my participants were much older, I would often attempt to sit by their feet, in an effort to replicate a cross- generational storytelling dynamic, between grandparent and grandchild, for example.

My ethnographic work took the form of loose, semistructured interviews. Where applicable, I tried to cover themes such as experience of violence, loss of home, migration, rebuilding life, and divided loyalties, but these themes were designed to be as broad as possible, and the narrative of the interview was always directly led by the participant’s own story. Transcripts from the interviews have been reproduced here as close to the original as possible. Interviews that were conducted in English have been reproduced verbatim, including grammatical “errors.” Interviews in other languages are my translation, unless stated otherwise, and I have tried to keep as close as possible to the sense of the original. Translations from non-Anglophone cultural sources are also my own, unless otherwise stated.

Nevertheless, this work is certainly affected by the same problem of power dynamic that most if not all ethnographic work has to face up to. At numerous points during my research—interviewing in what used to be refugee camps,23 crossing border checkposts easily by virtue of a British passport,24 being able to make numerous fieldwork trips by virtue of a generous research fellowship, hiring a car to interview in Karachi when the city was paralyzed by a general strike 25 I have been continually reminded of my own often privileged position, relative to many of my interviewees.

These lines of power were noticeable in many of my own interviews, and doubtless, can be felt in this book.26 It is notable, for example, that generally speaking, my interviewees in India were much more forthright about their dislike of Pakistan than vice versa, a phenomenon that is probably linked to me being perceived as Indian. In other words, my Pakistani participants might have felt that if they were honest about how they felt about India, they might offend me as a guest. Indian interviewees did not consider me to be a foreign visitor to the country, so did not feel the need to be polite.

Inevitably, not least because of my own family’s stories that appear in these pages, the reader should always be aware of my own presence in the ethnographic material that I present here. There is always a gap between ethnographic fieldwork and the “finished product” in the form of this book. In other words, in the selecting, editing, retelling, and interpreting, the voice that remains the most privileged is my own. I have tried to be as faithful as possible to the stories that I have been given, but the interpretation of those stories remains mine and mine alone. I am deeply aware of my duty to be fair to all of my participants but I am also keen to ensure that I am not “relinquishing our responsibility to provide our own interpretation.”27

Consequently, when referring to the people whom I interviewed, I use the words “participant” and “interviewee” interchangeably, mostly in order to

highlight the fact that I am acutely conscious of the problematic nature of all of these descriptive labels but that I am also aware that the power dynamic runs deeper than simply finding the right word to describe them. In referring to my interviewees in the pages of this book, I have typically provided a first name, the year and place of birth, and a religious and regional identity.28 There are, however, some notable exceptions. Some of my participants wanted to rename anonymous, so in their cases I have used initials. One participant agreed to take part on condition that I did not ask for her name. In that particular instance, I refer to her as X. I chose to do this rather than use pseudonyms to give their desire for anonymity more direct, typographic emphasis. In other cases, other participants have actively refused anonymity, urging me to identify them as authors of their stories. In those cases, and to respect their wishes, I have used their full names. The differing attitudes of my participants toward my project and their role in it reflects their immense diversity within my cohort, though I do not claim my cohort of interviewees to be representative of all survivors of partition

If the oral histories are not to be read as representative, then neither is the body of literature and cinema analyzed in these pages. Partition has spawned a body of cultural representation in the form of literature, cinema, and performative and visual art that is far too large to be tackled in any one book, let alone one that attempts to compare it with oral history. While I appreciate Ananya Jahanara Kabir’s call “to move beyond the scholarly preoccupation with narrative modes of remembering Partition,”29 I think there remains a need to study multiple forms of narrative together and to see how one genre may illuminate another. The primary mode of memory remains narrative and it is essential to see how these various narratives can both reinforce and undermine a notion of a centralized nationalist narrative that, in Kabir’s words, “a scholarly field would consider itself politically at odds with.”30 Thus I compare literary, cinematic, and artistic representations of partition with this body of oral history testimonies in order to look at the ways in which the events of partition are remembered, reinterpreted, and reconstructed, the themes that are recycled in the narration, and the voices that remain elided. Of course, the task of comparing memory narratives from so many different genres, periods, and geographical backgrounds poses many challenges of its own. However, I strongly feel that these challenges need to be faced. While it is important to allow for the specificity of the way texts of each genre (literature, cinema, oral history testimonies, etc.) are produced and received, it is equally important to examine the multifaceted ways in which memory works in society— from the private sphere of the family and home to establishing transnational, emotional relationships across space and time. Through my study of the various narratives, then, I identify common themes that appear in various different forms of representation and I examine how, through the ways in which these texts negotiate these themes, they often help to undermine various

state- endorsed myths of partition—for example, the idea that partition led to two oppositional, mutually exclusive nation states, and that people’s affective relationship with people and land, their religious identity, and the sociopolitical space of these new nation states could all be aligned in a simple, unproblematic manner. In turn, then, the book presents a different view on the nature of the historiography of partition—which allows for the articulation of marginalized voices, not just as victims but also as active agents who, through the narration of their stories, embody the desire to be seen as being in control of their own histories.

Finally, a point about nomenclature. While I use the word “partition” throughout this book for reasons of convenience, this name for the event is, of course, not unproblematic. Hindi and Punjabi speaking people who either stayed in India or traveled from Pakistan to India typically use the word batwara (“sharing out” or “division”). People who made the reverse journey, tend to use the Urdu word taqseem (perhaps the English word “distribution” comes closest). As an expatriate Bengali, the word that speaks to me the most is the word that is used almost universally by Bengalis— deshbhag. An English translation would have to be “division of the country,” though that would not do justice to the complexity of the original. Bengalis use the word desh to mean country (as in India), state (as in West Bengal), and, especially significant for migrant populations, the original home, village, or town where the family had to move from for economic or political reasons. So the word “partition” should be read as attempting to represent all these meanings. Perhaps as a result, I refrain from capitalizing the “P,” preferring the non- deified lower case instead. When I refer to places whose names have changed (Calcutta and Kolkata, for example) I aim to use the name that was current at the time of the events being discussed. The only exceptions are when I am quoting from interviews or cultural texts, in which case I quote the name that was used in the original.

Narrator as Agent

Given the power dynamic of ethnographic work, and given the undeniable national and individual trauma, it is perhaps surprising that I am choosing to focus on agency as the lens through which to analyze the textual material. Whatever else it may have been, partition was, undeniably, a great human tragedy and, moreover, one that is so immense that it seems to transcend the powers of language. However, the overwhelming focus on the pain, trauma, and loss does suggest that the only way in which marginalized voices can enter the discourse of partition is as victims—an implication that I find deeply problematic.31

We need a more complex and nuanced conception of agency in order to complicate the narrative of victimhood that so much oral history of partition

has become. Agency is, paradoxically, both a widely used and underdefined concept. Sumi Madhok, Anne Phillips, and Kalpana Wilson have written that agency is “in its dictionary definition . . . not much more than the capacity to act”32 a definition that is deceptive in its simplicity. The problem with this definition, as Madhok et al point out, is that, first, agency and coercion are assumed to exist “in a binary relationship of presence/absence”33 if one is a victim then one cannot have agency and vice versa; and, second, agency is almost always defined through action, or, as Madhok, herself has put it:

I am against limiting understandings of agency to the ability to act (freely or unfreely) and according to one’s freely chosen desires. . . . Instead, I argue that we must shift our theoretical gaze away from these overt actions to an analysis of cognitive processes, motivations, desires and aspects of our ethical activity.34

I am conceptualizing agency as always also narrative and thus broader than practically or symbolically emancipatory activism—the potential for change, as it is often defined. Like Saba Mehmood, I am not interested in “distinguish[ing] a subversive act from a nonsubversive one.”35 Rather, my use of agency is much closer to Helen M. Buss’s definition as “the ability of individuals to negotiate societal systems to make meanings for themselves”36 or, as Susan Hekman has put it, agency lies in the “piecing together” of subjectivities “out of the hegemonic and nonhegemonic discourses around them.”37 For my work specifically, a working definition of agency could be: the ways in which people exert narrative control over their memories and refuse to be defined by them. My interviewees exercise agency in the ways they construct narratives out of particular spaces and particular objects, and then are able to define themselves in relation to these narratives. Narrative agency does not have to be a conscious effort on behalf of the narrator; it may also be interpreted onto the narrative after the fact.

Applying this notion of narrative agency to testimonies of partition implies, as Deborah Youdell has pointed out, “a politics that insists nobody is necessarily anything.”38 While the author of a partition narrative may indeed be a victim, he or she most certainly does not have to be one. I read narrative agency, then, in the ways in which people establish connections with people, places, spaces, and objects, in order to exert linguistic control of their memories. Sometimes these narratives of connection may run counter to hegemony, sometimes they may not, but in either case they point to a more complicated subject position than mere victimhood.

Through my study of the oral history and cultural narratives, then, I identify particular strategies of narration which provide evidence of agency on the part of the narrators. These include agency through ownership of memory (“This is my story”), agency through forming alternative and counter-hegemonic

emotional relationships (beyond the privacy of the family or the community, for example, or across national borders), agency through mourning (“This was mine and I have the right to mourn its loss”), agency through complexity (the ability to maintain contradictory ideological positions without being defined by either), and agency through putting one’s direct and inherited memory to work in the form of employment practices, social and political activism, academic research, and literary and artistic practices. These strategies are not necessarily intended to be read as explicit articulations of agency, but nevertheless, it is my contention that evidence of agency is visible in the ways in which the memories are being narrated. My identification of narrative agency does not challenge any of the pain or grief or loss that is present, nor does it preclude my narrators from actively taking on the mantle of the victim. Rather, it allows for a more complex, nuanced view of agency that can and does coexist with narratives of oppression and violence.

If one is prepared to read these testimonies against the grain, as it were, one can find evidence that subverts the victim/survivor dichotomy, instead recasting the narrators as active agents who are able to exercise a degree of control over their memories and the ways in which they narrate them.

Narrative agency, as I am conceiving it, can be used productively to study “private” oral history testimonies and forms of cultural representation together. In fact, it is in this complex relationship that exists between public and private memory, in the ways in which people are able to fuse their most personal stories with those that exist in the public domain that I read narrative agency. Narrative agency, then, is employed by oral history interviewees, authors and filmmakers, and characters within texts in order to exert control over painful memories, and, through this control, construct oneself and one’s community as differently victim, survivor, perpetrator, savior, and so on.

Studying individual oral history testimonies along with cultural representation raises a really important issue—how to theorize the dynamic between individual and collective memory—that has been occupying scholars of memory studies for some time now.39 This book follows Rebecca Clifford’s position, in that narrative agency is exerted in and through the “dance between the lived memories of groups of individuals and the cultural visions of the past that have come to be called collective memory.”40

Within the form and structure of the narratives I am focusing on, there are many examples of contested agency between, for example, character and author in the case of cultural texts, or between the child who has experienced the event and the adult who is remembering it (in the case of the oral history interviews). Narratives thus become not just sites on which agency is inscribed but a contested domain over which competing structures of agency battle for primacy. Oral history testimonies and cultural representations alike are, then, complex spaces encompassing multiple voices, struggling to find expression, reminiscent of Mikhail Bakhtin’s analysis of the novel.41 These complex,

multilayered, multivocal texts contain within them the possibility of multiple layers of meaning, lend themselves to multiple modes of interpretation, and, therefore, help to exert narrative agency.

While upholding both the distinctiveness and the significance of narrative agency, we need to also be wary of its limits. In identifying my narrators as agents, it is important not to romanticize them as necessarily counterhegemonic and radical. There are often significant overlaps, for example, between individual and statist narratives of partition, but even in these cases, the testimony reveals a layer of complexity that does not simplistically allow for a pro- or counter-hegemonic reading. The complexities of the event that was partition and its equally complex afterlives demands a multidisciplinary exploration of its memorial legacies. Narratives are always messy, and it is this complex, chaotic messiness which allows contradictory stories and opposing extremes to be placed next to each other, thus demonstrating a narrator’s ability to exert agency over her narrative, and, therefore, by extension, over herself.

Memories of partition are marked by many forms of loss—the loss of home, the loss of family, the loss of childhood innocence, to name but a few. In the ways in which many of my narrators remember these losses, however, they often reject an externally imposed victimhood status by setting up alternative, interesting, counter-hegemonic narratives. I am troubled by the way in which individual grief at loss and separation gets appropriated through public discourse to represent a wider national trauma. Instead, the ways in which someone talks about one’s position relative to one’s lost family can be evidence of taking back control at a time when the narrator is more than usually disempowered.

This creative control can also be seen in the ways in which people remember and describe specific acts of violence—from where they locate it physically to the way they choose to negotiate its legacies. Violence took place in and around people’s homes, on trains and boats, on land and on rivers. The way people describe this violence, however, is marked by the narrator’s attempts to keep control over meaning, even when this control is contested both by wider hegemonic forces and by the ethnographer himself. People mourn in different ways, and specific acts of mourning do not necessarily imply passive victimhood. Articulating the right to mourn, in this context, needs to be read as a corrective to the imperialist act of partition, as well as official, hegemonic appropriation of individual, intimate, and often deeply private moments of loss.

These memories of loss are often put to work in a variety of different ways, from illegitimate or illegal economic activities on the part of refugees attempting to rebuild their lives in the years immediately after partition to literary and artistic practices, academic work, and community activism in the decades since. A closer look at how these people mobilize their memories and

family stories will show that partition needs to also be seen as a productive event, both in the sense that it not only helped to produce national, personal, and political identities but also helped to produce “work” in the form of academic research, artistic production, and social and political activism—all of which provide examples of the articulation of agency on the part of the narrating subjects.

Partition is remembered today in many complex ways; it affects people’s lives today in equally complex ways. Studying oral history and cultural representation together helps to remind us of the power that words may have in the ways in which stories of partition get told and retold. Thinking of this power that language has helps me to reflect on the personal dimension this work has had for me, and how my own life story has inflected the work in various ways, even as the work itself has come to rewrite my life story in various ways.

I hope my work helps to reflect the ways in which marginalized voices narrate the stories of partition, not just as victims but also as active agents. Through their narration, people enact the desire to be seen as being in control of their own histories. Again and again, in various ways, my narrators refuse the role of the victimized corpus on which history is seen to act. Instead, through various creative and productive ways, they take control of their memories of the past, and their identity narratives in the present, in order to not be defined by the pain of their memories. It is this creativity that I try to recognize in this book. Partition was and remains an individual, collective, and national trauma—the least those of us who are studying it and its legacies can do is not add to it by leaving out huge swathes of people, their voices, stories, and aspirations unrepresented, when we try to write the many histories of partition.