https://ebookmass.com/product/myth-locality-and-identity-in-

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

The Myth of Left and Right : How the Political Spectrum Misleads and Harms America Hyrum Lewis & Verlan Lewis

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-myth-of-left-and-right-how-thepolitical-spectrum-misleads-and-harms-america-hyrum-lewis-verlanlewis/

ebookmass.com

Pindar and the Poetics of Permanence Henry Spelman

https://ebookmass.com/product/pindar-and-the-poetics-of-permanencehenry-spelman/

ebookmass.com

Verb Movement and Clause Structure in Old Romanian

Virginia Hill

https://ebookmass.com/product/verb-movement-and-clause-structure-inold-romanian-virginia-hill/

ebookmass.com

Trigger Point Dry Needling: An Evidence and Clinical-Based Approach 1st Edition – Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/trigger-point-dry-needling-an-evidenceand-clinical-based-approach-1st-edition-ebook-pdf-version/

ebookmass.com

Summertime on the Ranch Carolyn Brown

https://ebookmass.com/product/summertime-on-the-ranch-carolyn-brown-2/

ebookmass.com

Midnight on the Marne Sarah Adlakha

https://ebookmass.com/product/midnight-on-the-marne-sarah-adlakha/

ebookmass.com

Wings Once Cursed and Bound Piper J. Drake

https://ebookmass.com/product/wings-once-cursed-and-bound-piper-jdrake/

ebookmass.com

Netter’s Head and Neck Anatomy for Dentistry (Netter Basic Science) – Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/netters-head-and-neck-anatomy-fordentistry-netter-basic-science-ebook-pdf-version/

ebookmass.com

Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications 7th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/discrete-mathematics-and-itsapplications-7th-edition-ebook-pdf/

ebookmass.com

The White Redoubt, the Great Powers and the Struggle for Southern Africa, 1960–1980 1st Edition Filipe Ribeiro De Meneses

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-white-redoubt-the-great-powers-andthe-struggle-for-southern-africa-1960-1980-1st-edition-filipe-ribeirode-meneses/

ebookmass.com

Myth, Locality, and Identity in Pindar’s Sicilian Odes

GREEKS OVERSEAS

Series Editors

Carla Antonaccio and Nino Luraghi

This series presents a forum for new interpretations of Greek settlement in the ancient Mediterranean in its cultural and political aspects. Focusing on the period from the Iron Age until the advent of Alexander, it seeks to undermine the divide between colonial and metropolitan Greeks. It welcomes new scholarly work from archaeological, historical, and literary perspectives, and invites interventions on the history of scholarship about the Greeks in the Mediterranean.

A Small Greek World Networks in the Ancient Mediterranean

Irad Malkin

Italy’s Lost Greece

Magna Graecia and the Making of Modern Archaeology

Giovanna Ceserani

The Invention of Greek Ethnography

From Homer to Herodotus

Joseph E. Skinner

Pindar and the Construction of Syracusan Monarchy in the Fifth Century B.C.

Kathryn A. Morgan

The Poetics of Victory in the Greek West Epinician, Oral Tradition, and the Deinomenid Empire

Nigel Nicholson

Archaic and Classical Greek Sicily: A Social and Economic History

Franco De Angelis

Myth, Locality, and Identity in Pindar’s

Sicilian Odes

Virginia M. Lewis

Myth, Locality, and Identity in Pindar’s Sicilian Odes z

VIRGINIA M. LEWIS

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress ISBN 978–0–19–091031–0 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

For Alexander Lewis Jr.

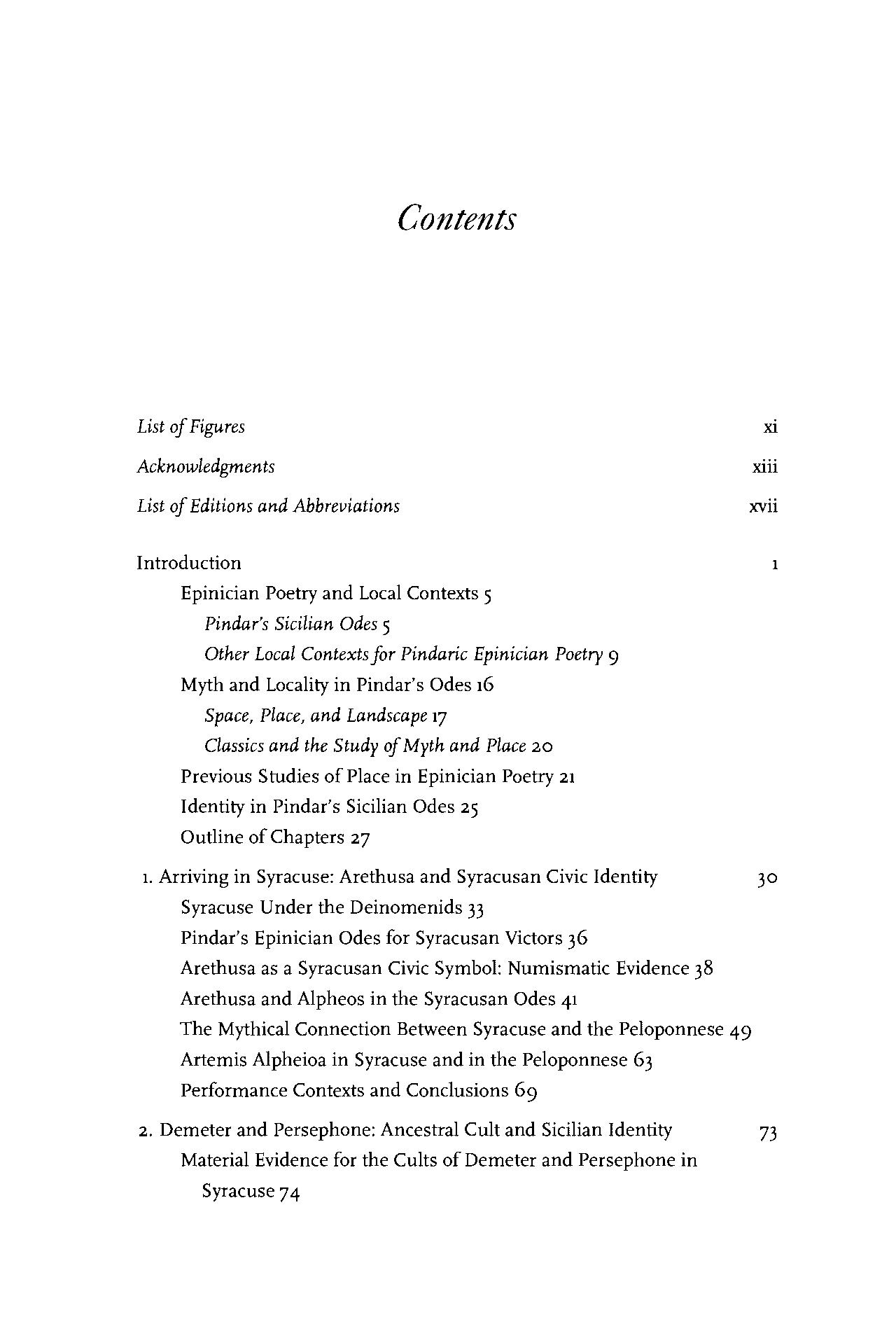

List of Figures

Acknowledgments

List of Editions and Abbreviations

Introduction

Epinician Poetry and Local Contexts 5

Pindar's Sicilian Odes 5

Other Local Contextsfor Pindaric Epinician Poetry9

Myth and Locality in Pindar's Odes 16

Space, Place,and Landscape17

Classicsand the Study of Myth and Place20

Previous Studies of Place in Epinician Poetry 21

Identity in Pindar's Sicilian Odes 25

Outline of Chapters 27

1. Arriving in Syracuse: Arethusa and Syracusan Civic Identity

Syracuse Under the Deinomenids 33

Pindar's Epinician Odes for Syracusan Victors 36

Arethusa as a Syracusan Civic Symbol: Numismatic Evidence 38

Arethusa and Alpheos in the Syracusan Odes 41

The Mythical Connection Between Syracuse and the Peloponnese 49

Artemis Alpheioa in Syracuse and in the Peloponnese 63

Performance Contexts and Conclusions 69 30

2. Demeter and Persephone: Ancestral Cult and Sicilian Identity 73

Material Evidence for the Cults of Demeter and Persephone in Syracuse 74

Demeter and Persephone in the Sicilian Mythic Tradition 79

Diodorus'Narrative of Persephone'sAbduction 84

The Deinomenid Priesthood of Demeter and Persephone 94

Herodotus94

Diodorus105

Pindar and Bacchylides107

Myth and Landscape in Pindar's Nemean 1116

A Syracusan Representationof Sicily in Nemean 1122

Reading Arethusa and PersephoneTogether129

Heraklesand Spatial Ideology132

Conclusions 135

3. Locating Aitnaian Identity in Pindar's Pythian 1

The Foundation of Aitna and the Cult of Zeus Aitnaios 142

The Myth of Zeus and Typho 150

Earlier Versionsof Zeus' Suppressionand Imprisonment ofTypho 152

Typho'sAitnaian Prison in Pythian 1 158

A Myth for the Citi2ens of Aitna 171

Conclusions 177

4. Fluid Identities: The River Akragas and the Shaping of

Akragantine Identity in Olympian 2

Akragas Under Theron's Rule 180

Emmenid vs. Deinomenid Commemoration 183

Pindar's Odes for Akragas 187

The River Akragas and the Mediation of Emmenid Identity in Olympian 2 189

The River Akragas as a Civic Symbol BeforeTheron'sRule 189

Locatingthe Emmenids: Placeand Identity in Olympian 2 195

A Heroic Genealogyfor Theron 205

Akragas and the Isle of the Blessed211

Theron, Son of Akragas 219

Conclusions 223

5. Conclusions and Test Cases: Ergoteles of Himera and Psaumis of Kamarina

The Immigrant Victor: Becoming Himeraian in Olympian 12 227

The Native Victor: Psaumis as Local Benefactor in Olympians 4 and 5 234

Conclusions 24 7

Bibliography

Figures

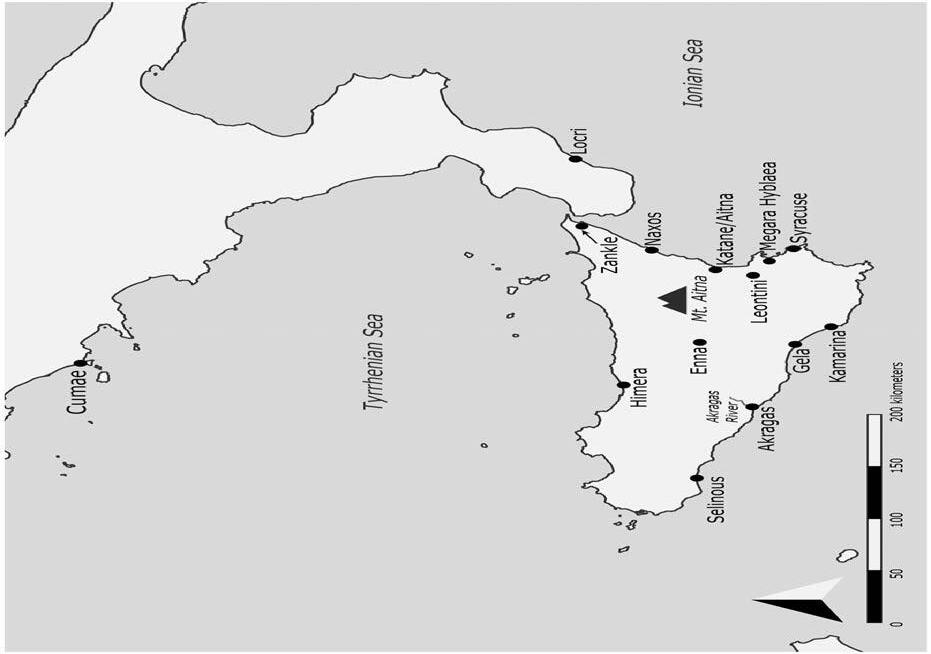

0.1 Map of Sicily and Southern Italy. xvi

1.1 Syracusan Tetradrachm, Silver, ca. 500–485. 40

1.2 Syracusan Tetradrachm, Silver, ca. 485. 53

2.1 Ennaian litra, Silver, ca. 450–440. 83

2.2 Geloan Didrachm, Silver, ca. 490. 128

3.1 Aitnaian Tetradrachm, Silver, ca. 475–470. 144

3.2 Aitnaian Tetradrachm, Silver, ca. 465–460. 145

4.1 Akragantine Tetradrachm, Silver, ca. 505–500. 190

4.2 Himeraian Drachm, Silver, ca. 530–500. 192

4.3 Himeraian Didrachm, Silver, ca. 483–472. 192

5.1 Himeraian Tetradrachm, Silver, ca. 470–464. 233

5.2 Kamarinaian Litra, Silver, ca. 461–440. 242

Acknowledgments

Like the poetry that it studies, this book has been shaped by multiple places and the people who live in them. In this case, it was my great fortune that they were inhabited by generous teachers, colleagues, and friends, who supported and encouraged me as the book developed. I was first introduced to Pindar while I was a graduate student at the University of Georgia. I thank Charles Platter and Nancy Felson for guiding my early research on epinician poetry and for their continuing support. The seeds of this project were sown in graduate seminars at UC Berkeley. I am grateful to the Classics faculty, especially my dissertation committee members—Mark Griffith, Emily Mackil, and Donald Mastronarde—for encouraging me to pursue this line of inquiry, challenging me to improve my ideas, and saving me from countless errors as the dissertation progressed. I owe my greatest debt to Leslie Kurke, who advised my dissertation and whose research and teaching have shaped my approach to Pindar’s poetry. Her support and guidance were critical both throughout the dissertation process and as the project expanded and evolved. My colleagues at Florida State University have been unfailingly generous with their time, advice, and encouragement of the project. I am especially appreciative of the mentorship of John Marincola, with whom I co-organized a Langford Conference in Tallahassee on “Greek Poetry in the West” in Spring 2017 that stimulated discussion related to the book and influenced my thinking as I wrote the final chapters. Generous support from the FSU Council on Research and Creativity in the form of a First Year Assistant Professor Award and a Committee on Faculty Research Support Award allowed me the time and space for writing and revision at crucial moments. I am grateful to the Department and the Dean of Arts and Sciences for granting me leave to spend a semester as a fellow at the Center for Hellenic Studies in Spring 2017. The support of writing groups and writing intensive workshops at FSU was essential as I finished the project. Thanks to Laurel Fulkerson and Peggy WrightCleveland for organizing these groups that introduced me to other writers at

Acknowledgments

the university and modeled the writing group form. Kristina Buhrman, Celia Campbell, Jessica Clark, Matt Goldmark, Katherine Harrington, Jeannine Murray-Román, Svetla Slaveva-Griffin, and Erika Weiberg infused energy and focus that sustained me during the final phase of the project. Special thanks are owed to Sarah Craft for making the map of Sicily and Southern Italy printed in this volume.

The Center for Hellenic Studies offered me the chance to test my ideas among a friendly and collegial group of Hellenists during Spring 2017. I am grateful to the Senior Fellows for this opportunity. Special thanks to my fellow fellows Maša Ćulumović, Jason Harris, Greta Hawes, Naoise Mac Sweeney, Michiel Meeusen, and Nikolas Papadimitriou for engaging discussions of myth and place that influenced my approach to Pindar’s poetry, especially when they took a roundabout path. I benefited from visits by Nancy Felson and Daniel Berman to the Center, and I am grateful to them for sharing their unpublished work. Conversations with Gregory Nagy, Nikolaos Papazarkadas, and Laura Slatkin following the Fellows Symposium improved the arguments in chapter 4.

Many others contributed their time and effort to this project from afar. Carmen Arnold-Biucchi helped me track down images of the Alpheos/barley grain tetradrachm. Hanne Eisenfeld was a valuable interlocutor on myth and place in Pindar’s poetry, and I am thankful for her input on earlier drafts. I owe a debt of gratitude to Nigel Nicholson, who has supported the book from its very early stages through to the end, reading and commenting on drafts of the entire manuscript and encouraging me at each turn.

Special thanks to Stefan Vranka at Oxford University Press for his patience and invaluable assistance as this book came into its final form, to Christopher Eckerman for his attention to detail on an earlier version (as a then-anonymous reader), and to the other two anonymous readers whose suggestions greatly improved the manuscript. Earlier versions of arguments in the book were presented at meetings of the Society for Classical Studies, the Classical Association of the Middle West and South, and the Classical Association, and at UC Berkeley, FSU, the University of Georgia, the Center for Hellenic Studies, and the First and Third Interdisciplinary Symposia on the Hellenic Heritage of Southern Italy in Syracuse, Sicily. I am grateful to members of these audiences for thoughtful questions that advanced my ideas. All errors that remain are my own.

Finally, I am grateful to my friends and family for conversation, encouragement, and support. I thank Wiktoria Bielska, Sasha-Mae Eccleston, Allison Kirk, Sophie McCoy, Leithen M’Gonigle, Nandini Pandey, Anna Pisarello, Melissa Rooney, Dan Scott, Randy Souza, Sarah Titus, Naomi Weiss, and

Acknowledgments

especially Beth Coggeshall, Athena Kirk, Rachel Lesser, and Sarah Olsen, who read and gave feedback on multiple drafts, occasionally at the very last minute. My family members, and above all my parents, have been a constant source of care and enthusiasm. I dedicate the book to my grandfather. Over the seventeen years I knew him, he continually asked when I would finally learn Latin, but he passed away before I discovered the pleasure of studying and teaching ancient languages. I hope he would have forgiven me for writing a book about Greek literature instead.

Figure 0.1 M ap of Sicily and Southern Italy.

Editions and Abbreviations

i use the following editions for citations of Pindar, Bacchylides, and the Scholia to Pindar:

Drachmann, A. B. 1903–1927 Scholia vetera in Pindari carmina. 3 vols. Leipzig: Teubner.

Maehler, H. Ed. 2003. Bacchylidis Carmina cum Fragmentis. Leipzig: Teubner. Snell, B., and H. Maehler. Eds. 1987. Pindari Carmina cum Fragmentis, Pars I. Epinicia. Leipzig: Teubner.

Snell, B., and H. Maehler. Eds. 1989. Pindari Carmina cum Fragmentis, Pars II. Fragmenta, Indices. Leipzig: Teubner.

Although influenced by William Race’s Loeb editions, all translations of Pindar’s poetry (and of other Greek authors) are my own except where otherwise indicated.

When printing names of Greek places, characters, and authors, my aim has been to use the most recognizable terms possible, but there are some inevitable inconsistencies. I have retained Latinized forms of the names of many well-known places and authors (e.g., Syracuse and Aeschylus rather than Surakousai and Aiskulos) for ease of recognition, but in other cases names have been transliterated from the Greek (e.g., Aitna, Kamarina, and Herakles) to align more closely with the terminology employed by other scholars of these subjects.

The abbreviations of ancient authors and works follow those in the Oxford Classical Dictionary, with the following exceptions:

BCH 1877–. Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique. Paris: Thorin et fils.

BNJ Worthington, I. Ed. 2006– Brill’s New Jacoby. Leiden: Brill.

FGrH Jacoby, F. Ed. 1923–1958. Die Fragmente der griechischen Historiker. 3 vols. Berlin: Weidmann.

xviii

List of Editions and Abbreviations

LIMC 1981–2009. Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae Zurich: Artemis.

LSJ Liddel, H. G., and R. Scott. Eds. 1940. A Greek-English Lexicon. Revised and augmented throughout by H. S. Jones, with the assistance of R. McKenzie, with a supplement (1968). 9th ed. Reprint ed. 1990. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

PMG Page, D. L. Ed. 1962. Poetae Melici Graeci. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

POxy Grenfell, B. P. Ed. 1898–. The Oxyrhynchus Papyri. Vols. 1–. London: Egypt Exploration Fund.

TrGF I Snell, B. Ed. 1986. Tragicorum Graecorum Fragmenta. Vol. 1. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

TrGF III Radt., S. Ed. 1985. Tragicorum Graecorum Fragmenta. Vol 3. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Pindar’s epinician odes are abbreviated as follows:

I. Isthmian

N. Nemean

O. Olympian

P Pythian

Introduction

i n a review of Adolf Köhnken’s monograph Die Funktion des Mythos bei Pindar (“The Function of Myth in Pindar”), Malcolm Willcock makes the following observation about myth and local place in Pindar’s epinician poetry:

After all, we know Pindar’s ‘τέθμιον’ [“custom”]—when in Aegina, tell of the Aeacidae; when in Opus, be (if possible) Opuntian; when writing for a Sicilian tyrant—as there are no comparable Sicilian myths, it being a new country—find some large and enhancing story, perhaps related to the place where the victory was won.1

Willcock’s assessment of myth in the Sicilian odes assumes that the “new” status of the cities in Sicily prevented them from having developed local mythic traditions. This view of myths in Pindar’s odes for Sicily is representative of general attitudes; other scholars have similarly argued that Sicily lacked the kind of established mythological tradition found in other Greek cities in the fifth century for Pindar to incorporate into celebrations of Sicilian victors.2

1. Willcock 1974: 192.

2. See, for example, Rose 1974: 155–56, Hubbard 1992: 81. Morrison 2007: 26 argues that there were no heroes associated with Sicilian cities. Though there may have been fewer ties between Sicilian cities and heroes in the way that the Aiakids were linked to Aegina, there are strong regional ties to Herakles, for example, that this statement overlooks. For the importance of Herakles in Sicily, see Diod. 4.23–26, 5.4, Giangiulio 1983, and now also Nicholson 2015: 258–61. To address the apparent lack of Sicilian mythical narratives, Morrison 2007: 123 proposes that Pindar favors Panhellenic heroic narratives rather than local “so that audiences across the Greek world will be interested in his re-telling of these myths, and hence in his victory odes in general, thus enabling the spread of the victors’ fame.” However, Morrison underplays the role of local Sicilian places in these myths.

Myth,Locality,andIdentityinPindar’sSicilianOdes. Virginia M. Lewis, Oxford University Press (2020). © Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190910310.003.0001

This book reevaluates the role and nature of myth in Pindar’s epinician poetry for victors from Sicily, who come from Syracuse, Aitna, Akragas, Himera, and Kamarina. Willcock characterizes Sicily as a “new” country, yet four of the five Sicilian cities celebrated by Pindar were founded at least one hundred years before Pindar celebrated them in song, and Syracuse—a city celebrated in four odes—was founded in the eighth century. Most of these cities were not, then, new, and the country surrounding them was even less so since it had been inhabited by native Sikels before the arrival of the Greeks. Yet, even as we observe that these cities were not new in a historical sense, there is some truth in Willcock’s characterization. All five cities experienced regime changes and, in most cases, stasis in the first decades of the fifth century, and their populations were reorganized and transferred—either by choice or by force—from one city to another. From this perspective, the cities and the country surrounding them were “new.” Τhis study will explore the strategies by which Pindar engages in a striking, innovating style of mythmaking that represents and shapes Sicilian identities in this poetry for people and places that were “new” in the sense that their communities were undergoing rapid change and redefinition.

Willcock’s observation about the Sicilian odes highlights an underlying strategy in Pindar’s odes by which this poetry represents Sicily as a “new” country whose status is up for negotiation and definition by the epinician poet. I will propose that within a volatile political climate where local traditions were frequently shifting, Pindar’s poetry supports, shapes, and negotiates identity for Sicilian cities and their victors by weaving myth into local places and landscapes. We shall see that the links between myth and place that Pindar fuses in this poetry reinforce and develop a sense of place and community for local populations while at the same time raising the profile of physical sites, and the cities and peoples attached to them, for larger audiences across the Greek world.

This book will take a historicizing approach to the Sicilian odes. Whereas older historicists tended to view the epinician poems as reflections of or evidence for historical events,3 in the 1960s, Elroy Bundy, building upon the work of Wolfgang Schadewaldt, offered an important corrective to their approaches by focusing on formal analysis and examining the rhetorical conventions that make up the genre of epinician poetry.4 More recently, scholars have stressed the idea that the mindsets created and reinforced by epinician poetry

3. Wilamowitz 1922 is one of the most influential examples.

4. Schadewaldt 1928, Bundy 1962.

shaped the civic communities in which they were performed. Following the publication of Leslie Kurke’s The Traffic in Praise in 1991, which convincingly argued that New Historicist approaches should be applied when interpreting Pindar’s epinician odes, the majority of scholars of Pindar and Bacchylides now recognize that reading these odes in their social, political, and historical contexts helps to elucidate aspects of this poetry that cannot be understood through formal analysis alone.5 This is not to say that we should abandon the careful study of the odes’ literary effects; rather, the literary effects of Pindar’s epinician poetry—as poetry that was composed for a specific victory from a particular city in a certain year—should be interpreted within their historical and cultural contexts.6

When I speak of reading texts within their cultural contexts, I am situating my project within a framework of Cultural Poetics, wherein texts are understood as sites of cultural contestation.7 Culture, in this view, is not a static system but instead a dynamic force that is constantly being shaped and negotiated by groups with differing interests within society. Texts not only reflect but also react to, shape, and influence the cultures within which they are created, performed, and received. As a collection of varied interests and perspectives, theorists have argued that culture should be viewed as an “indissoluble duality or dialectic” of “system and practice.”8 Texts, as sites of contestation and participants in culture, give rise to and are inscribed with ideology. Following Gramsci, Catherine Bell defines ideology as “not a disseminated body of ideas but the way in which people live the relationships between themselves and their world, a type of necessary illusion.”9 Embedded as it is in lived experience, ideology is complex, unstable, and continually changing.10

5. For studies of Greek choral poetry that emphasize readings within a broader cultural and historical context see, among others, Calame 1997, Herington 1985, Gentili 1988, Krummen 1990, Nagy 1990, Kurke 1991, 2005, 2007, Stehle 1997, Fearn 2007, Kowalzig 2007, Morgan 2015, Nicholson 2015.

6. For a more detailed, recent discussion of the merits of a historicizing approach, see Morgan 2015: 5–9. For arguments against, see Nisetich 2007–2008, Sigelman 2016: 7–10 with references.

7. My discussion of Cultural Poetics in this paragraph follows Kurke 2011: 22–25. See also Foster 2017: 4–6. For New Historicism as it relates to the theory of Cultural Poetics, see Stallybrass and White 1986: 1–26. Dougherty and Kurke 1993: 1–12 and 2003: 1–19 demonstrate the relevance of Cultural Poetics to the study of ancient Greek literature and culture.

8. Sewell 1999: 46–47, quote taken from p. 47.

9. Bell 2009: 85.

10. Bell 2009: 81–82, Macherey 2006: 75–101.

Furthermore, ideology is not singular and uniform, but at any point in time multiple ideologies coexist, which compete both with one another and with the remnants of older ideologies.11 Like other texts, the epinician poems of Pindar and Bacchylides participated in, contributed to, and were influenced by the complex set of overlapping identities and ideologies that constituted the fifth-century Greek city. The premise that epinician poetry participates in the negotiation and shaping of cultural systems has motivated my decision to examine the Sicilian odes together as a set of poems within shared Sicilian historical and cultural contexts throughout this study.

A focus on the Sicilian odes will allow us to identify and analyze cultural features that are uniquely Sicilian in a broad sense and also to distinguish those features that are more specifically linked to individual cities. One of the most distinctive and remarkable aspects of Pindar’s epinician odes is the variety of cities and civic contexts they celebrate. While nearly all complete surviving tragedies from the fifth century were primarily written for performance before Athenian audiences,12 Pindar’s forty-five epinician odes celebrate victors from seventeen different cities. The wide range of victors and cities commemorated in the odes makes them among the best surviving sources for understanding the different sociocultural circumstances that existed in fifth-century Greece. An increased scholarly focus on Greek choral poetry as embedded in the community in which it was performed has highlighted ways that sets of poems for individual cities can productively be read alongside one another to shed light on local culture and history. Scholars have, for instance, explored the dynamics of Pindar’s poetry in the poet’s hometown of Thebes, and in other cities and regions whose victors were celebrated by the poet, such as Aegina, Sicily, and Rhodes.13 This book’s focus on the Sicilian odes makes it possible to identify trends that apply across the region and, conversely, to recognize traditions and poetic strategies that are particular to individual civic communities.

11. Smith 1988, Jameson 1981.

12. There are known exceptions: Aeschylus’ Aitnaiai was certainly first performed in Sicily, and it is possible that some surviving tragedies were first performed outside of Athens. For example, Bosher 2012a makes the case that Hieron may have commissioned Aeschylus’ Persians for a first performance in Syracuse. Still, Athens was the center of production of Greek tragedy in the fifth century.

13. Important recent examples include Kurke 2007, Olivieri 2011 (on Thebes); Larson forthcoming (on Orchomenos); Kowalzig 2007 (on Delos, Argos, Aegina, Rhodes, South Italy, and Boiotia); Morrison 2007, Morgan 2015, and Nicholson 2015 (on Sicily and Southern Italy); Burnett 2005 and the studies in Fearn 2011 (on Aegina); and Kurke and Neer 2014 (on Athens).

Epinician Poetry and Local Contexts

Pindar’s Sicilian Odes

Despite the rich variety of local communities that we know existed in the fifth century, Athens tends to dominate our literary sources and therefore also often dominates our narratives about fifth-century Greece. As I mentioned above, one reason that the epinician odes are important and especially interesting is that they offer us rich perspectives on cities outside of Athens. Each of the seventeen different poleis that Pindar celebrates represents a unique political community, and several of them, like Aegina, Cyrene, and Rhodes, were wealthy and powerful in the fifth century. While some of these poleis are very well represented (e.g., victors from Aegina are celebrated in ten odes), other places are barely represented (e.g., there is only one surviving ode for a victor from Rhodes and there are no surviving odes celebrating victories by Spartans). Studies that concentrate on sets of odes from a particular city or region allow us to identify civic symbols and patterns with greater certainty because we can see that they recur in multiple odes for the same place.14

Still, one might reasonably ask: Why focus such a study on the Sicilian odes? What makes them distinctive? And are they different from Pindar’s other epinician odes? One of the most basic reasons why the Sicilian odes are particularly interesting for a study focused on locality is that the number of surviving odes written for Sicilians is so large. Of Pindar’s forty-five epinician odes, fifteen celebrate the achievements of Sicilian victors.15 Of these odes, four celebrate victors from Syracuse (O. 1, O. 6, P. 2, P. 3), five from Akragas (O. 2, O. 3, P. 6, P. 12, I. 2), three from Aitna (P. 1, N. 1, N. 9), two from Kamarina (O. 4, O. 5), and one from Himera (O. 12). In all but one case, the Sicilian cities are celebrated in more than one ode, and this relative abundance of evidence for each city will allow us to track the symbolic vocabulary Pindar uses from poem to poem and to trace the intersections of myth and landscape in several passages and, in some cases, through different time periods and political contexts in odes for the same city.

In addition to the relatively large body of material available for this region, the Sicilian odes are particularly worthy of study because of Sicily’s prominence in the fifth century. By the sixth century, the Sicilians and Southern Italians participated regularly at Olympia, sending athletes to compete and 14. On the productivity of reading these odes as a group, see Fearn 2011: 175–76.

15. O. 1, O. 2, O. 3, O. 4, O. 5, O. 6, O. 12, P. 1, P. 2, P. 3, P. 6, P. 12, N. 1, N. 9, I. 2. In addition, O. 10 and O. 11 celebrate Alexidamos, a victor from Locri in Southern Italy.

making conspicuous dedications.16 After the Deinomenids took control of Syracuse in 485, they controlled most of eastern Sicily, though other key cities (and, in particular, Akragas) maintained their independence. After the Greek victory at the Battle of Himera in 480, Syracuse became the dominant political power in the region. The city was, furthermore, renowned for its wealth in antiquity. Strabo says that the Syracusan founder, the Corinthian Archias, went to Delphi at the same time as another founder, Myscellus: “When they were consulting the oracle, the god asked them whether they chose wealth or health; now Archias chose wealth, and Myscellus health; accordingly, the god granted to the former to found Syracuse and the latter, Croton.”17 Strabo’s report of Archias’ consultation of the oracle, whether or not it is historically accurate, demonstrates that Syracuse’s wealth was one of the city’s most fundamental and defining characteristics in the Greek imagination, and in fact we shall see that Pindar celebrates Syracusan agricultural wealth, in particular, by making allusions to myths embedded in the local landscape. Sicily was also an important center for philosophical and literary culture.18 The Sicilian poets Empedokles and Epicharmus, for example, were important figures in the development of Greek philosophy and poetry.19 During the period when Pindar composed the epinician odes for him in the 470s, Hieron invited several internationally famous poets (including Pindar, Bacchylides, Aeschylus, Simonides, and perhaps also Phrynichus) to Syracuse and transformed the city into a major cultural center.20 After the fall of the Deinomenids in Syracuse, the citizens established a democratic government that lasted through the Athenian attack on the city during the Peloponnesian Wars until the tyrant Dionysius came to power in 403.21 The famous debate

16. Phillip 1994.

17. Strabo 6.2.4, trans. Jones.

18. On literary and performance culture in the West, see Morgan 2015: 87–132.

19. Porphyry, for example, seems to believe that editing the work of Epicharmus is a project that can be compared to editing the work of Aristotle (Porph. Plot. 24). On Epicharmus, see Guillén 2012.

20. For the suggestion that Phrynichus traveled to Syracuse as part of this group and that his Phoenician Women was performed in the city, see Morgan 2012: 49 and Morgan 2015: 98. Simonides celebrated victories by the Emmenid tyrants of Akragas and possibly a victory of Gelon, on which see Morgan 2015: 72–73. Later in the fifth century, Xenophon imagines a fictional conversation between Hieron and Simonides in the Hieron. On the variety of poetic performance in Sicily in this period, see also Dougherty 1993: 83–102.

21. The Deinomenids, like the Peisistratids in Athens, preceded a period of democracy in Syracuse. On the institution of the democracy, Diod. 11.72.2. Aristotle cites Syracuse after the

represented in Thucydides between Nicias and Alcibiades over whether or not to attack the Syracusans highlights the importance of this city, and of Sicily in general, as a threat and rival to the Athenians. The cultural and political importance of Sicily in Greek politics throughout the fifth century merits further investigation of the social and political role of choral poetry composed for and performed on the island.

The Sicilian odes, and especially the odes celebrating the Deinomenid and Emmenid tyrants, represent some of Pindar’s most celebrated poetic masterpieces. Although interpreters of Pindar’s poetry have always been interested in these odes, in the past twenty years, several studies have now been devoted to the Sicilian odes as a group.22 Sarah Harrell’s 1998 dissertation, “Cultural Geography of East and West: Literary Representations of Archaic Sicilian Tyranny and Cult,” considers the ways in which Herodotus, Pindar, and Bacchylides shape Deinomenid identity by associating the tyrants with the east, west, or center of the Mediterranean world. In particular, she argues that such geographical associations align the Deinomenids with eastern tyrants like Croesus.23 More recently, Andrew Morrison has examined the issues of performance and reperformance in Pindar’s Sicilian odes, and his readings emphasize that passages in these odes would have had different meaning for audiences of diverse origins and during performances at different points in time.24

Two recent monographs that examine Pindar’s epinician odes in their Sicilian and Southern Italian frameworks are especially worthy of note and have been influential for this project. First, Kathryn Morgan’s monograph, Pindar and the Construction of Syracusan Monarchy in the Fifth Century B.C., has provided both a thoughtful contextualization of Pindar’s odes for Hieron and his circle in their historical and cultural contexts, and subtle close readings of this set of odes.25 In particular, Morgan offers new perspectives on the ways that Pindar characterizes Hieron’s kingship in the Syracusan odes.

fall of the Deinomenid tyrants as an example of the way a tyranny can change into a democracy (Politics 1316a28–34).

22. In addition to the monographs mentioned in the following notes, other important recent discussions of Pindar’s Sicilian odes include: Harrell 2002, 2006, Hornblower 2004: 186–201, Currie 2005 (258–95 and 344–405 on Syracusan odes P. 2 and P. 3), Kowalzig 2008, Bonanno 2010, Thatcher 2012, and Foster 2013.

23. Harrell 1998.

24. Morrison 2007.

25. Morgan 2015.

In addition, Nigel Nicholson’s The Poetics of Victory in the Greek West has considered hero traditions in the Greek oral tradition alongside Pindar’s epinician poetry for victors from Western Greece, focusing on this region because so many competitors at the Olympic games came from the area.26 One particular type of hero narrative, the “hero athlete narrative,” he argues, was especially relevant to epinician poetry and represented an ideological tradition that was fundamentally opposed to the representations of the athlete presented in epinician poetry. Where Morgan offers new perspectives on the way that Pindar shapes Syracusan kingship and Nicholson offers a new understanding of the form of epinician poetry for victors from the West, this study will build upon these earlier inquiries to illuminate the ways in which Pindar’s interweaving of myth and place in odes for the five Sicilian cities he celebrated shaped Sicilian identities.

In response to observations that the cities in Sicily lacked local myths for Pindar to celebrate, I will demonstrate that rich mythological traditions did, in fact, exist in Sicily by the fifth century when Pindar composed his odes for Sicilian victors. It is certainly the case that in some instances, for example in Hieron’s newly founded Aitna, a city was founded so recently that completely new traditions appear to have been invented to represent it and its citizen body. But the city of Aitna, founded in 476, was more the exception than the rule. Other Sicilian cities, such as Syracuse (whose traditional foundation date is 733 bce), had been in existence for centuries and had developed strong mythological and civic traditions that were available for Pindar to draw upon and allude to in his odes.

The following discussion will not only show that local Sicilian mythological traditions existed within larger systems of civic ideology but will also make a claim about the character and role of these myths. Like the citizens of other cities throughout the Greek world, Sicilian Greeks worshipped many gods. However, the particular mythological and religious figures Pindar incorporates into his epinician poetry for these cities hold especially close ties to the local landscape and topography.

This close association between mythological representatives of the city and the local landscape reflects the political instability in Sicily during a period when the Deinomenid tyrants, Gelon and Hieron, ruled cities inhabited by “mixed populations.”27 Later in the fifth century when, according to Thucydides, the Athenians debated whether or not to send an army to attack

26. Nicholson 2015: 79–98.

27. Diod. 5.6.5, Thuc. 6.17.2–3, see also chapter 1.

Syracuse, Alcibiades argued that the Syracusans would be easily defeated because they were a group of mixed citizens who lacked civic loyalty. Alcibiades’ claims about the Syracusans ultimately underestimated the Syracusans, who united to defeat the invading Athenian army. Nevertheless, his statements did capture an essential aspect of Sicilian politics, especially in the first half of the fifth century. After Gelon took over the city of Syracuse in 485, for instance, the citizens of Syracuse included former citizens of Gela, Kamarina, Syracuse, Leontini, and Naxos, many of whom had been forcibly moved to Syracuse from their former cities.28 When his brother Hieron came to power, he not only inherited this mixed group of Syracusan citizens, but he also relocated the people from the neighboring cities of Katane and Naxos to Leontini and established yet another group of mixed citizens in his new colony of Aitna in 476. Though Aitna is a unique example, this kind of political volatility was the norm in Sicily during the period, and it created the need for the reinforcement and reworking of notions of identity—both those of the citizens and of their rulers.

The political volatility in fifth-century Sicily created an environment in which it is possible to observe the stabilizing and community-building potential of epinician poetry at work. When political and social cohesion are especially threatened, tools that are able to foster unity and shape a common sense of purpose may be employed particularly powerfully in an effort to encourage or to regain political stability. This book proposes that one strategy for creating stability amidst this kind of political turmoil was to connect identity of various kinds to fixed elements in the landscape, such as mountains, rivers, and springs, that remained stable and were not tied to a single group of people, ruler, or ruling family.

Other Local Contexts for Pindaric Epinician Poetry

The fifteen odes for Sicilian victors are important sources for Sicilian culture in the fifth century, but they also belong to the larger body of Pindaric epinician poetry and should be understood in that context as well.29 Before exploring some of the ways in which the Sicilian odes are unique in Pindar’s corpus in the upcoming chapters, it is worth considering how the poet marks local contexts in some of his epinician poems for cities outside of Sicily. There is not space here

28. Hdt. 7.156, Thuc. 6.4.2.

29. The fifteen Sicilian odes are, by city: O. 1, O. 6, P. 2, P. 3 (Syracuse); P. 1, N. 1, N. 9 (Aitna); O. 2, O. 3, P. 6, P. 12, I. 2 (Akragas); O. 12 (Himera); and O. 4, O. 5 (Kamarina).