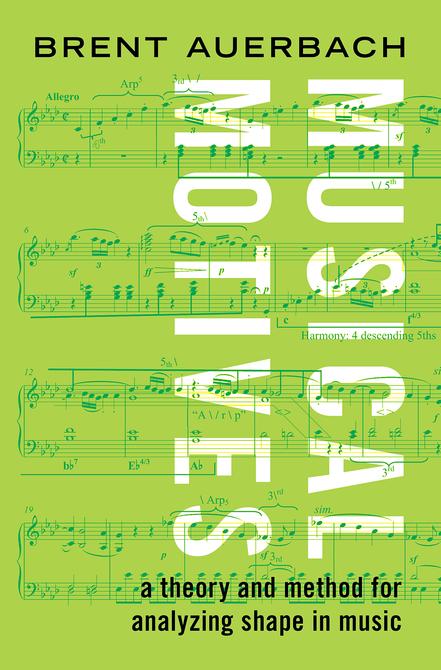

Musical Motives

A Theory and Method for Analyzing Shape in Music

BRENT AUERBACH

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Auerbach, Brent, author.

Title: Musical motives : a theory and method for analyzing shape in music / Brent Auerbach. Description: [1.] | New York : Oxford University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020025132 (print) | LCCN 2020025133 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197526026 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197526057 (oso) | ISBN 9780197526033 (updf) | ISBN 9780197526040 (epub) Subjects: LCSH: Musical analysis.

Classification: LCC MT90.A87 2020 (print) | LCC MT90 (ebook) | DDC 781.2—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020025132 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020025133

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197526026/001.0001 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Integrated Books International, United States of America

To my wife, Meli, and my daughters, Isabel and Natalie, for their boundless love and support.

Interlude

PART III: ANALYSES AND CONCLUSION

Acknowledgments

I would like to first to acknowledge my dear friends and colleagues at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. This project could never have come to fruition without their support. To Gary Karpinski, Jason Hooper, and Chris White: thank you for all of your advice generously given about how to improve this work. I owe a special debt to Jason Hooper for his adept co-mentoring and for sharing his impeccable research on nineteenth-century conceptions of form and motive. I would like to thank Erinn Knyt and Roberta M. Marvin for their advice on navigating the publication and post submission process, and Chair Salvatore Macchia for graciously protecting my time in the critical last months leading up to manuscript submission. Laura Quilter, the Copyright and Information Policy Librarian on campus, deserves recognition for helping me to fully understand and to negotiate my publishing contract. Thanks go, last, to the graduate students in the Department of Music and Dance, who bravely volunteered to serve as test subjects for Musical Motives. Their feedback, both in and out of the classroom, proved invaluable for improving the book’s style and content.

My sincere thanks go also to the Society for Music Theory for its generous assistance in the form of a subvention grant helping to cover permissions and indexing fees. I offer my gratitude as well to the Massachusetts Society of Professors and UMass’s College of Humanities and Fine Arts for their sustained and generous professional support in the form of travel grants and computer replacement funds.

Further afield, I benefited greatly from the help of colleagues who saw and commented on early versions of this book. Thanks go to Rob Haskins, my good friend dating back to my Eastman days, for aid proofing the manuscript, and to Scott Murphy at the University of Kansas for his insights and ideas for correcting inconsistencies in the chapter on complex motivic analysis. Sincere thanks go as well to René Rusch and Brad Osborn for their helpful suggestions for carrying out research on Radiohead. In particular, I am grateful to Alan Street at the University of Kansas for his suggestions on broadening and strengthening the portions of the method concerning narrative. His expertise and research have not only impacted this project, but also will serve in perpetuity as resources in my research and pedagogy.

My deep thanks go as well to Suzanne Ryan, former Editor in Chief in Humanities at Oxford University Press, for believing in this project and for expertly shepherding it through all but the very last stages of the publication

process. Her feedback and suggestions, simultaneously pithy and kind, provided the clearest guidelines imaginable for taking the next step forward through draft revisions. Thanks go, as well, to the capable, supportive staff at OUP—to Sean Decker, in particular—for their quick, informative, and good natured responses to every minute query I sent their way.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge my loving, supportive family, for—how else to put it?—everything! To my parents, Lisa and Richard: thank you for setting me on the path for a life in music and for encouraging me at every step to continue its pursuit. To my other parents, Ada and José Matos: thank you for all you do to help keep my household happy and well fed, from emergency school bus service to regular, world-class dining served at your home and delivered as take-out. Last, I thank my precious wife, Melissa, and children, Isabel and Natalie, for their love, good humor, and occasional interest in my work. Each of them amazes me, daily, for who they are and for their willingness to share this life with me.

1 Introduction to Motives

Motives Play a Central Role in Music

There are not many absolute truths that can be asserted about music, but here is one: all music moves.1 The physical embodiment of music, sound waves, causes particles in the air to vibrate. This in turn causes listeners’ eardrums and then their basilar membranes, brains, and bodies to do the same. That’s all well and good, most musicians might think, except that this first attempt at describing musical “motion” falls far short of capturing what music truly is. Music is not mere sound waves, although it may be best enjoyed when it actually hitches a ride on these invisible sails. (Even when it sounds purely in the realm of imagination, the inner ear, music remains essentially music.) It is a sound-based art that communicates sensation, emotion, and energy; it impels us to feel, to dance, and to think. This awareness of what music is gives us cause to revise our original assertion. It is not just that all music moves, but that music moves us.

We take this first point about music and movement as axiomatic. We next extend it with a claim that will ground this book: through exploring the mechanisms by which music moves and moves us, we stand to gain understanding about art and ourselves. Above, I summarized the path by which musical waves manifest in the body, but how does music pervade our senses and our consciousness? The answer is suggested by laws of perception known as Gestalt principles that describe how our brains involuntarily process stimuli, sonic and otherwise. For example, humans tend to group together pitches that share attributes such as frequency, timbre, and volume. (The well-known “law of common fate” in the visual domain offers an example: a swarm of dots all moving together gives the impression of a larger, single entity in motion.) If we lacked this ability, the concept of melody would likely never have developed in any culture. In musical settings, we would be wholly unable to untangle the mass of sound waves arriving at our eardrums into coherent strands. There would be no way to distinguish between “more important” (solo) and “less important” (supporting) material. In listening to a rock band play, it would be impossible to tell which sounds were coming from the singer and which from the drums, bass, and guitars.

Although scientists who study the brain hardly ever take for granted our reliance on the processes that render human-intentioned sounds in the air into music, the rest of us usually do. Anyone who enjoys, plays, or simply “gets” music

Musical Motives. Brent Auerbach, Oxford University Press. © Oxford University Press 2021. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197526026.003.0001.

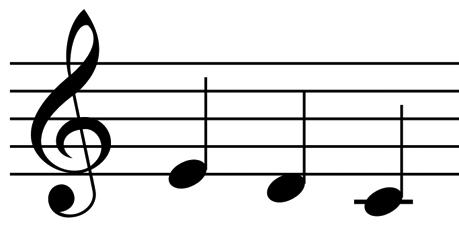

does so by grace of a grand illusion that transforms streams of particulate sensory data into coherent wholes. In the case of music, the standard bit of data is a note, which by itself does not communicate a whole lot of musical meaning. To confirm this, imagine the sound of a single, brief E4 played in the central register of the piano, as shown in Example 1.1.2

Now imagine your reaction to my declaration that you’ve just heard a whole piece of music. Pretend that this “Sonata in E” is being offered to the public with no ironic or metaphysical wink. You can assume that this pseudo-micromasterpiece is meant as music and not as some highfalutin’, aesthetic statement about music. In other words, it is not supposed to provoke any “big” questions like “What is the essence of a ‘piece’ of music?” Even so, you’d find this piece fatuous. A single note hardly constitutes even the barest musical idea.

The piece is now newly expanded. In Example 1.2, the E4 is connected to a D and then a C, with all of the notes played briefly and in close register. This second effort is also not much of a piece, but it is at least recognizable as something. Something wonderful has happened in that three separate notes are forged into a coherent, descending, moving line.3 We have generated a recognizable musical shape in motion, our first example of a musical motive.

Having broached the topic that will occupy our attention for the duration of this study, we are not yet ready to address the bigger question, “What is a motive?” We will postpone that activity to chapters 2 and 3, where paired historical surveys of the concept will prepare and inform a comprehensive method for identifying, linking, and interpreting these shapes. A working definition will have to do for now. Our starting point will be the conception of motive put forward by Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951), the composer-theorist whose writings and teachings were instrumental in establishing motivic analysis as a modernday discipline. As Schoenberg worked on the manuscript meant to enshrine his

Example 1.1 A single note, E4.

Example 1.2 The one-note piece is extended to three notes.

fully realized theory of music, he defined motive as “the smallest part of a piece or section of a piece that, despite change and repetition, is recognizable as present throughout” (1995, 169).4

The open-ended character of Schoenberg’s definition, meant to render the term “motive” flexible and intuitive, may also be seen as impractically vague. Consulting his many writings, however, affords us with a set of more useful particulars. For instance, it is clear that for Schoenberg a motive is a small entity, typically shorter than a four-measure phrase in common or triple time. A motive’s identity may derive from any musical domain, including articulation, timbre, or harmony. Inclusion of this last area means that, for Schoenberg, a chord progression may serve as a motive, although that occurs less often in practice. In the vast majority of published analyses, including those by Schoenberg, motives are generally assumed to be melodic, monophonic, entities. To facilitate the present introduction to the concept, we will initially fall back on that assumption. In later chapters, this view will be broadened to allow for more complex, polyphonic motives that are more analytically rich.

In a separate treatise, The Fundamentals of Musical Composition, Schoenberg explains that a melodic motive is encoded primarily by its “intervals and rhythms, combined to produce a memorable shape or contour which usually implies an inherent harmony” (1967, 8). Rhythmically, a gesture as small as a two-note pickup figure may qualify. Similarly pitch-wise, a bare two-note configuration (a basic intervallic second, third, fourth, etc.) can serve as a motive in analysis. Often the domains of pitch and rhythm work together: the profile of the three note shape from Example 1.2 would be sharpened if, in a larger work, it always appeared in a characteristic rhythm such as q q h. But this does not always happen. In many instances, analysts will equate one set of pitches with another in the same piece, even when the gestures have no rhythm in common.

The adagio excerpt by Mozart shown in Example 1.3 illustrates a case in which pitch motives act independently of rhythm. The first melodic gesture shown in brackets is a “neighbor” figure, C5–D♭–C, set in a dotted, siciliana rhythm. The shape is imitated in pitch and rhythm in the alto and tenor voices in mm. 2–3. The pattern of descending entries suggests the bass should eventually have it, too, and so it does in mm. 5–7. The characteristic rhythm disappears; however, the neighbor shape’s pitch-intervallic connection remains strong and audible.5 By virtue of being set in more ponderous, dotted half notes, the neighbor motive figure seems to gain stature and importance.

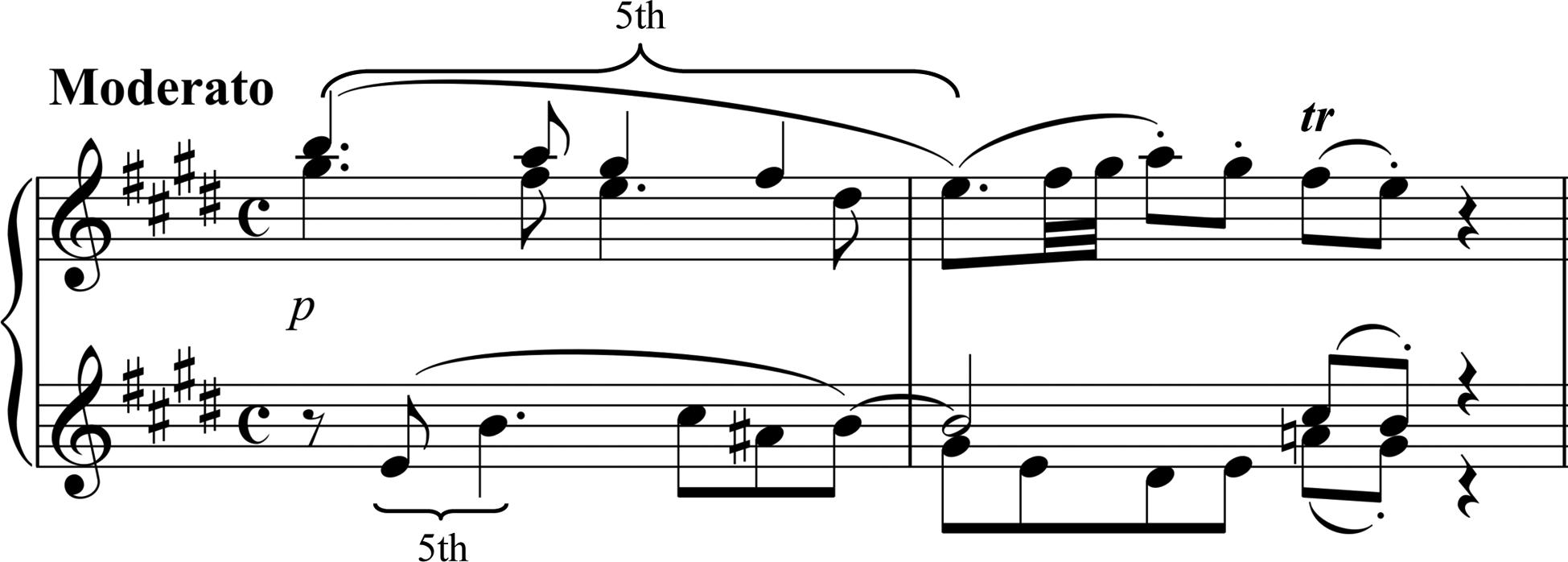

Even in cases where this kind of patterning is absent, an open interval can sound striking enough to suggest itself as an important span to be explored. In Haydn’s Piano Sonata 31 in E, Hob. XVI: 31 I, shown in Example 1.4, the first melodic gesture heard is given by the left hand. It is the intervallic fifth, E4-B.

Example 1.3 Neighbor (N) motives in Mozart’s Piano Sonata in F, K. 280 (II), mm. 1–8.

Example 1.4 Opening of Haydn’s Piano Sonata in E, Hob.XVI: 31 (I).

The melody takes longer to move from its first high B5, but as it does it traverses the same letter-note span in reverse, B down to E. The two zones of activity, both fifths, echo each other.

It is worthwhile to mine Schoenberg’s writings for technical guidance in how to treat motives. That task will in fact be the focus of major portions of a later chapter. Yet at the same time that we strive to read between the lines of Schoenberg’s definition to discern more and less “correct” methods, we should keep another approach in mind. To wit, we should embrace the notion that Schoenberg’s imprecise mode of communication, in its own ideal way, conveys valuable information. It may not directly answer the question “What does a motive look like?”; however, it squarely addresses an equally important concern, “What is the essence

of motive?” Here we may expressly link the words “recognizable” and “memorable” from our previous Schoenberg quotations. The two terms are functionally equivalent. Memorability emerges as the essential measure of music’s “unity, relationship, coherence, logic, comprehensibility, and fluency” (Schoenberg 1967, 8). Memorability, it turns out, is everything for Schoenberg.

It is easy to test whether a motive within a piece is memorable. The process is personal, intuitive, and efficient, and even today remains the primary means for determining which figures in a work qualify as motivic. As a practical matter, the memorability requirement allows us to derive a working set of subrequirements. A motive must

• be short enough to fit in memory

• be distinct enough from its surroundings to be perceived as a whole, and

• exhibit sufficient character to compel listeners’ attention.

There is a further advantage in acknowledging the role of memory. Doing so prioritizes subjectivity and musicianship in analysis, accurately reflecting the fact that all listeners will hear or remember a piece in different ways.

Schoenberg’s conception of motive has proved itself sufficiently sturdy, having remained largely in effect for almost a century now. Nonetheless, it could do with some fortification; an update is well past due. Though academics and performers of all stripes to this day routinely work with motives, these entities often serve an auxiliary function in their analyses. Few scholars at present seek to analyze the motivic content of a piece, in and of itself. Instead their primary goal is usually to examine a work’s form, harmony, counterpoint, and/or narrative. Motivic connections, when noted at all, usually are mentioned in asides or footnotes.

Where motives play this kind of supporting role in analysis, authors have two reasons for pointing them out. One is to bolster evidence for conclusions already reached by other means. Often, it seems that the more complicated and technical the primary method is, the more pressing the need to defend it in terms of an audible motivic connection. Another reason authors turn to motivic analysis is to demonstrate their cleverness. Even where a motivic relationship is not central to the primary analytic argument, an author will usually mention it anyway. The temptation to exhibit her credentials as an analyst possessed of deep musicality and ingenuity is too strong to pass up.

As we shall soon see, music is oversaturated by motives. This condition is a boon, artistically. Most composers think in motivic terms as they write. Consciously or not, they begin by designing a set of shapes and then take inspiration in deciding how to deploy them from one passage to the next. When listeners later partake of their creations, the underlying unity of motivic content within registers as coherence, with all ideas seeming to connect logically.

Concurrently, the overabundance of motives in music causes problems, analytically. This condition, together with the flexibility of Schoenberg’s “memorability” clause, means it is usually possible to assert some kind of motivic connection between any two events in a work, no matter how dissimilar. It also means that motivic analysis can yield irrelevant, nonsensical results when carried out without sufficient training or care. Example 1.5 from Sharpe 1983, shows how one could begin with the E♭ minor theme from Beethoven’s Sonata in C minor (Pathétique), movement I, and gradually transform it into the theme from the Colonel Bogey March 6

Sharpe’s demonstration is designed to produce a laughable result; therefore, both it and its accompanying claim that “there is something wrong with a theory that allows” for such shenanigans may be set aside (Sharpe 1983, 279–280). The goal of motivic analysis is not to impose far-fetched readings on works. It is to clarify the nature of already-intuited connections. As in all things musical, this requires a fair amount of analytic know-how. Convincingly establishing a motivic connection between dissimilar shapes is difficult. An analyst must sense the underlying unity, seek an explanation for the similarity—hidden correspondences in pitch, rhythm, contour, and so forth—and effectively communicate the finding to the audience.

The musical community has long regarded motivic analysis with ambivalence. Analysts have generally been unwilling to give up on a practice that yields rich and rewarding results, but at the same time they cannot help viewing it skeptically. One barrier to motivic analysis’s acceptance is the long-standing awareness that few rules exist for identifying and associating motive forms, which amounts to saying that no proper theory of motivic analysis exists. The solution to this problem entails advancing a consistent set of rules for working with motives. Other barriers to acceptance are cultural in nature. In addition to the distrust held by many scholars and specialists about the viability of motivic analysis, there is the matter of the general low regard held for it by musicians of all types.

One might guess that the problem stems from musicians not having had enough experience in working with motives. The situation is quite the opposite, in that motives and motivic analysis have become overexposed. Most performers and academics are aware that little shapes and rhythms recur throughout pieces, having sat before a score with an instructor or a colleague watching him draw circles around scads of seemingly insignificant pitch configurations. Charles Rosen, in a staged moment of doubt, fills two pages of an essay with a host of trite analytical findings to show “how easy motivic analysis can be.” He asserts that it can “be taught in five minutes to any student, [who] can produce term papers on motivic analysis while watching television or doing anything else that engages his mind while leaving his hands free” (Rosen 1994, 95).

These are harsh words from Rosen, but his agenda is, fortunately, constructive. His aim is to rescue motives by reframing the questions we ask of them, namely: “What has the composer done to make us responsible for hearing these

Example 1.5 Abuse of analytic transformation technique (Sharpe 1983, 279–280). The numbers that appear in line (a), which indicate “order position,” track specific note shifts that occur in subsequent lines.

relationships?” and “How else do these invariances enter into the experience of the work?” (1994, 97). Questions such as these take motives seriously by acknowledging their role in musical structure and by weaving them into the listening experience.

The spirit of this book endeavor is closely aligned with Rosen’s. Instead of suggesting a single avenue toward elevating the status of motives, I will propose and proceed down many. I start with the premise that the concept of motive can be strengthened as new attributes are grafted on to it. The chapters and interludes that follow will carry out this task by introducing increasingly stringent definitions and rules. The first and perhaps most important step will occur in the philosophical realm, as Schoenberg’s classical definition is extended. My formulation, which embodies the musical truth declared at the outset, is as follows:

Proposition 1: For a musical figure to earn motivic status it must not only be memorable, but must move and move us.

The two new requirements “to move” and “to move us” overlap to a large extent; however, as a thought experiment, it is useful to try and tease them apart. Let us think for a moment what it would mean to develop a comprehensive theory for explaining how musical particles are able first, to instantiate motion, and second, to provoke listeners’ emotions. Were that endeavor to succeed, it would not only cement the importance of motives; it would also establish them as the smallest possible elements that can be music. For anyone who wishes to truly understand music, it is hard to imagine a worthier set of structures to examine than the ones constituting its very essence.

How Motives Move and Move Us

Our original E4-D-C shape from Example 1.2 will serve us one last time as we further explore how motives embody motion and musical meaning. The three pitch events occur successively and thus take time to traverse a distance: this fulfills the basic definition of motion. The shape, furthermore, stands in direct opposition to any single-note utterance—for example: just the E alone—that by itself implies no continuation or direction. By extension, no piece can proceed forward except through the activity of motives.7 With regard to moving us, this is where the aforementioned Gestalt principles come into play. If listeners consciously engage the shape as it forms, then at the moment the final C sounds there will be a real sense that they have moved along with it. Physiologically speaking, each note heard is a note recreated, or “re-performed” in the brain, immediately and internally.8

Each listener traverses the same journey that the notes do and in the same time. That experience is universal. What remains individualized is the manner in which different listeners feel and conceptualize their journeys. Listener TM, a trained musician, might imagine herself inside the musical texture, thus experiencing a downward glide through space. Listener NM, a nonmusician less familiar with the up/down metaphor of pitch, might regard the notes externally as moving toward or pulling away from him.9 If the E4-D-C gesture is played more rapidly, it becomes more likely that the two listeners will hear the tones fitting within one beat. The shape will still be experienced as motion, but perhaps in different ways. Listener TM now might feel the shape as a footfall in a purposeful stride forward, while NM may only be able to perceive it as a kind of energy that coils up and then is released.

The mechanism just described can be represented by the following graphic:

motive motion

The arrow is double-headed, allowing for implication to flow in both directions. The heads are of different sizes, though, to reflect the unequal logical status of the two claims. All motives suggest motion; however, motion in music is not created purely though motivic activity.

The next link in the chain in the experience of hearing music is that connecting the sensation of motion with the experience of emotion. This slightly more complicated mechanism can be represented as follows:

motive motion

emotion

The close linguistic correspondence between the latter terms, “motion” and “emotion,” is hardly coincidental. One of English’s main words for denoting state of mind, “emotion,” derives its meaning from a reference to literal motion. The Oxford English Dictionary dates this usage to as early as 1330, when if something “moved the blood” it meant that it excited or stirred a passion.

This connection invites us to speculate on a mechanism by which musical motives produce emotion. The motives of a piece, consciously attended to or not, are perceived as figures in motion. The listener’s mind hears these shapes while simultaneously re-creating them. This produces a cascade of novel thoughts. The brain’s self-awareness that it is thinking new things and traveling through virtual space—and all this quite without effort!—causes pleasurable sensations: feelings of inspiration, joy, excitement, and so forth. This mental activity engenders secondary physiologic responses in the brain, where neurotransmitters are triggered and neurochemicals released, and in the body, where heart rate and vasodilation are impacted by hormonal signals.10 In the

end it seems there is something to the Old English notion of “moving the blood” after all.

This informal proof of the causative link between motive and emotion is perhaps unnecessary, but it remains valuable. Taking the time to consider the mechanism that links sound, mind, and body helps us to appreciate the primary role motives play in the musical experience. This, again, helps establish their legitimacy as objects of inquiry. We can only advance our argument so far, though, by speaking in terms of a single, abstract third-motive (E-D-C) and idealized listeners. In the next stage of our philosophical excursion into the role of motives, we open the frame to include some concrete, real-world examples.

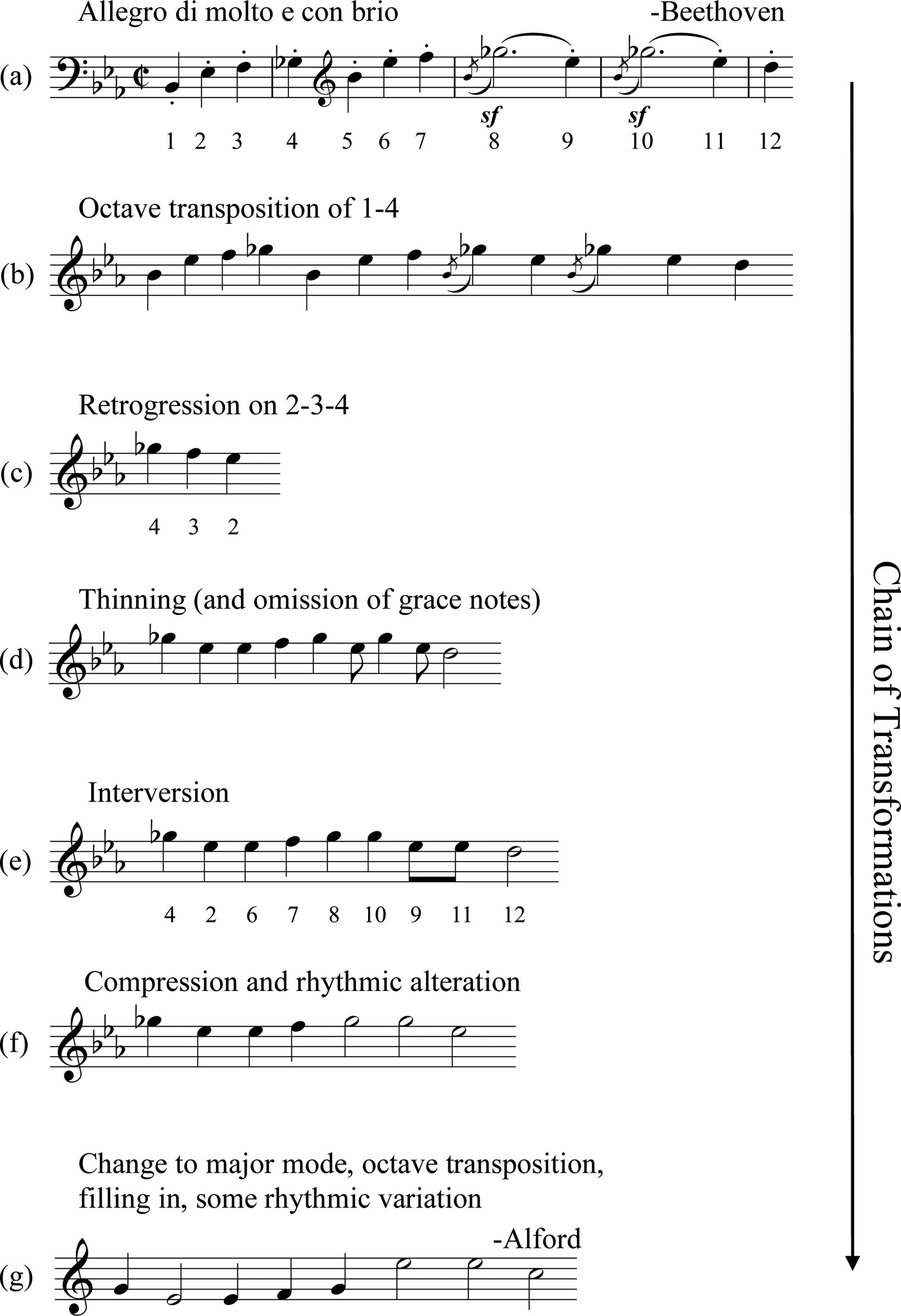

The discussion will move beyond the issue of what motives look like to consider how they interact. The typical textbook account of motives’ behavior conveys some accurate and useful information. Readers who consult introductory texts on musical form learn that motives may recur dozens or even hundreds of times throughout a piece, aiding the sense of flow in the music. Before all that repetition happens, motives typically combine early on to generate a piece’s larger primary melodies, otherwise known as its themes. This process is illustrated in Example 1.6, where an early theme from Sousa’s Liberty Bell march is shown to be made up of four motives.

To facilitate analysis, each unique motive is given a label. For this purpose, analysts traditionally have used neutral symbols such as “Motive X” or “Motive alpha” or loosely descriptive names such as “Neighbor figure.” The analysis in Example 1.6 strives for greater precision in labeling by referring wherever possible to pitch interval content, namely 3rds (see pickup figure and mm. 3–4), 4ths (mm. 3–4), and 2nds/stepwise motion (the neighbor shape in m. 1). By means of the brackets above and below the staff, the graphic further indicates how multiple motivic interpretations may arise.

The clinical accounts given in musical dictionaries offer the bare and true facts about motives but illuminate little about their inner life. Our response will be to step back and take motives in with a fresh perspective. This endeavor has already begun, in fact, with our earlier etymological study of the word “motive.” It continues now with an illustration of additional roles played by motives that

Example 1.6 Motives combine to form a theme in Sousa’s Liberty Bell, mm. 5–8.

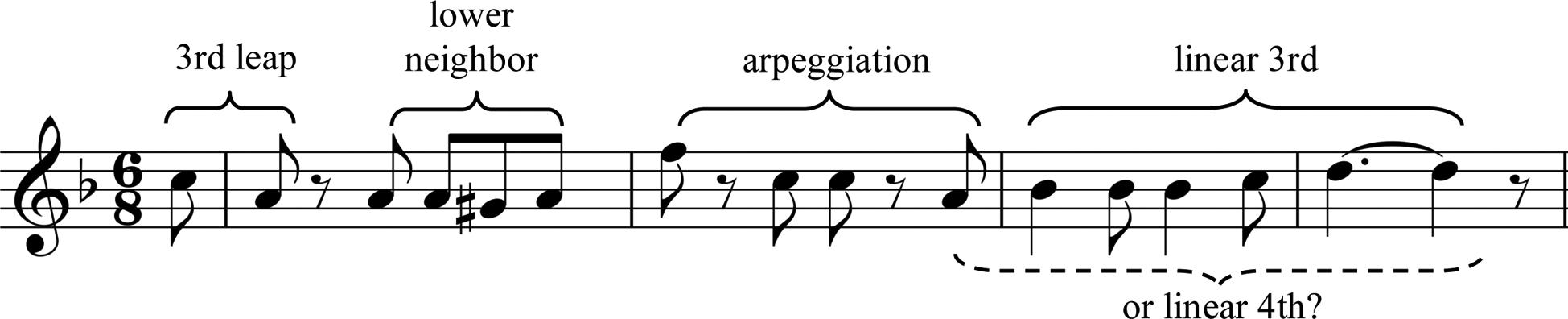

Example 1.7 The primary motive as a texture element in Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 (I).