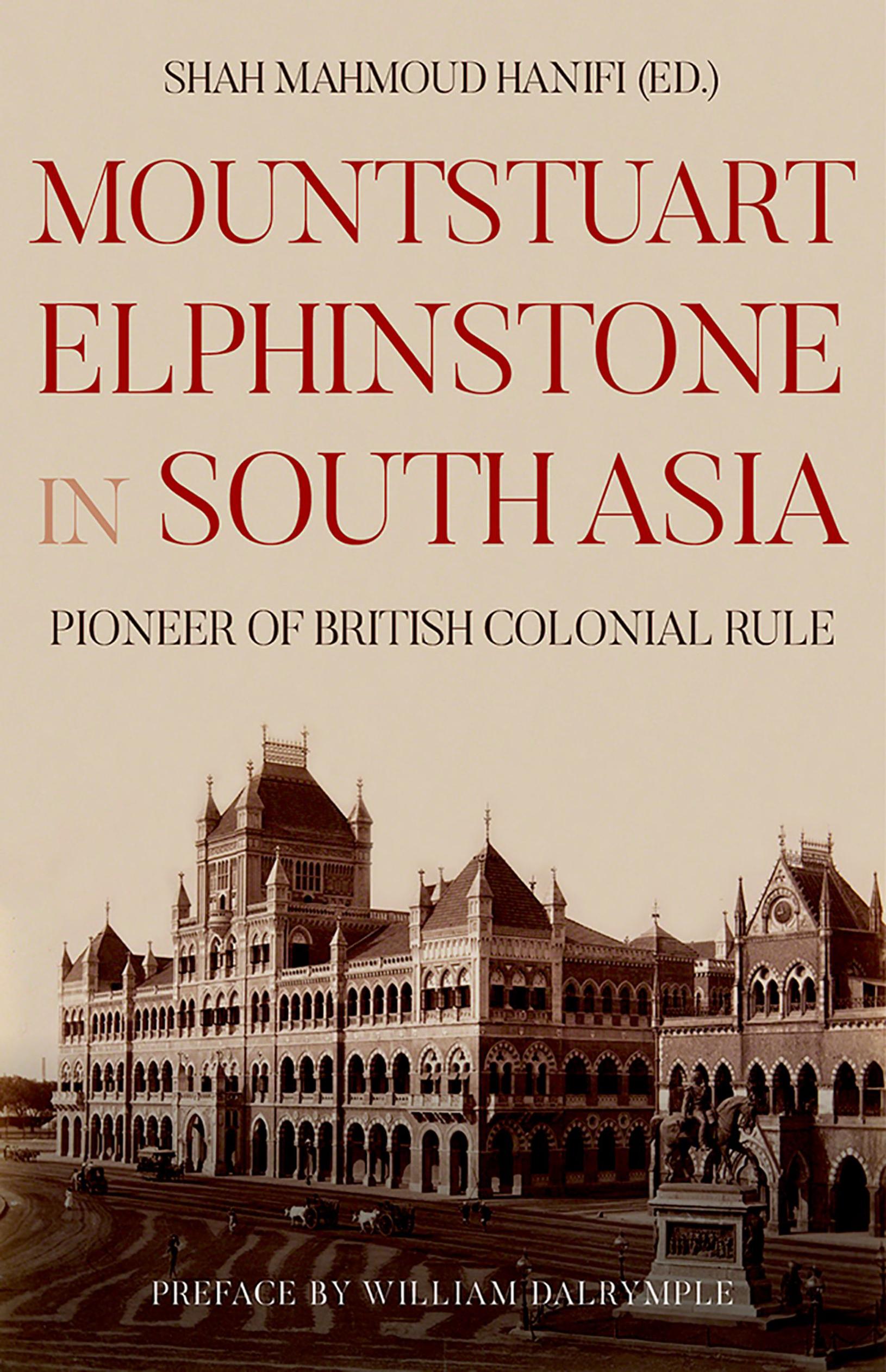

Mountstuart Elphinstone in South Asia

Pioneer of British Colonial Rule

3

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

© Shah Mahmoud Hanifi and the Contributors, 2019

First published in the United Kingdom in 2019 by C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd

All rights reserved. No part ofPublication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

A copy of this book’s Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-1909-1440-0

This book is dedicated to the memories of Sir Christopher A. Bayly and Clifford Edmund Bosworth most esteemed and generous scholars whose humanity continues to inspire

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements ix

Contributors xiii

List of Illustrations xvii

Preface: A New Source for the Elphinstone Mission William Dalrymple xix

Introduction Shah Mahmoud Hanifi 1

PART I

MOUNTSTUART ELPHINSTONE AND AN ACCOUNT OF THE KINGDOM OF CAUBUL

1. A Book History of Mountstuar t Elphinstone’s An Account of the Kingdom of Caubul Shah Mahmoud Hanifi 17

2. Mountstuart Elphinstone: An Anthropologist Before Anthropology M. Jamil Hanifi 41

3. The Elphinstone Mission, the ‘Kingdom of Caubul’ and the Turkic World Jonathan Lee 77

4. Muslim ‘Fanaticism’ as Ambiguous Trope: A Study in Polemical Mutation Zak Leonard 91

PART II

MOUNTSTUART ELPHINSTONE AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES

5. The Discovery of Afghanistan in the Era of Imperialism: George Forster, Mountstuart Elphinstone, and Charles Masson Senzil Nawid 119

6. Lieutenant Henry Pottinger and 150 Years of Baloch History

Brian Spooner 139

7. Information and Affect in Charles Metcalfe’s Mission to Lahore, August 1808–May 1809

Robert Nichols 149

8. Mountstuart Elphinstone and Indian Education

Lynn Zastoupil 167

9. Can Imperialists Produce Knowledge? The Case of James Grant Duff’s History of the Mahrattas Spencer A. Leonard 183

PART III

MOUNTSTUART ELPHINSTONE: COMPARISONS AND LEGACY

10. Elphinstone, Geography, and the Spectre of Afghanistan in the Himalaya Kyle Gardner 205

11. Forgetting like a State in Colonial North-East India

Thomas Simpson 223

12. Mountstuart Elphinstone, Colonial Knowledge and ‘Frontier Governmentality’ in Northwest India, 1849–1878

Martin J. Bayly 249

13. The Soviet Elphinstone: Colonial Histories, Post-Colonial Presents, and Socialist Futures in the Soviet Reception of British Orientalism Timothy Nunan 275

14. Elphinstone and the Afghan-Pathan Elision: Comparative British and American Approaches in the Twentieth Century

Elisabeth Leake 299

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book is the first in a series of volumes organised around Mountstuart Elphinstone, and it arises from a 2015 conference held in London. It is the product of a collective effort and I am pleased to recognise the individuals and organisations that made it possible.

At James Madison University, Dr Lee Sternberger, Director of the Center for Global Engagement, has been supportive of this project from the start and I could not be more grateful to her. Dr Sternberger’s staff, including Judy Cohen, Zina Gillis and Gerri Rigney also have my supreme gratitude. It was an honour to have the presence of Dr Sternberger and Dr Jerry Benson, then JMU Provost for Academic Affairs, at the 2015 London conference.

Beyond JMU, the London conference occurred as a result of a tremendous amount of assistance from the American Institute of Afghanistan Studies, particularly the AIAS President, Dr Thomas Barfield, and the US Director, Ms Mikaela Ringquist. I am grateful to AIAS for its generous support of the Elphinstone Project.

I am elated to finally have this chance to thank the Founding Director of the Council of American Overseas Research Centers, Dr Mary Ellen Lane. Dr Lane has been a source of encouragement since I was a graduate student and she was an original supporter of this project. Dr Lane’s successor, Dr Chris Tuttle, was also remarkably supportive, and Monica Clark and Heidi Wiederkehr in the CAORC office always uplifted me with their encouraging words. I am very grateful for CAORC’s support of the Elphinstone Project.

The 2015 Elphinstone conference occurred over the course of two days. The first conference day was hosted by the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies. At SOAS, Dr James Caron supported this project from its inception and he knows I cannot thank him enough. For administrative support, Dr Caron coordinated with the then Director of the SOAS South Asia Institute, Dr Michael Hutt, who also has my gratitude. In terms of the labour and energy required to micro-manage the conference-in-motion, I am very happy to express my gratitude to Dr Francesca Fuoli, then a graduate student at SOAS. Dr Fuoli worked with the graduate student-driven Muslim South Asia Research Forum (MUSA) at SSAI to arrange everything most wonderfully. I greatly appreciate MUSA’s collective effort in support of the conference.

The second day of the Elphinstone conference was held at the British Library. I thank Ms Aimee Sharman and her team at the Conference Centre for making all the necessary arrangements to host us. The conference included a private viewing session of archival documents related to Mountstuart Elphinstone’s 1808–10 diplomatic mission to the Afghan court that are now held at the BL. It is a joy to express my appreciation for curatorial assistance to Margaret Makepeace and Penny Brook, whose combined efforts allowed for a memorable documentary experience for the conference participants.

The conference was enhanced by the presence and active contribution of representatives of the Elphinstone family. It was an honour to have the 19th Lord Elphinstone and 5th Baron Elphinstone, Alexander Mountstuart Elphinstone, and his mother, the Dowager Lady Willa Elphinstone, at the conference. I am grateful to the Elphinstone family for their interest in and support of the London conference and larger Elphinstone Project.

It is a special pleasure to express my gratitude to William Dalrymple for his conference presentation and his contribution to this volume. I am also very pleased to thank Michael Dwyer for taking an interest in this project, and for all of their various inputs, Michael’s team at Hurst & Co. has my gratitude as well.

This volume is comprised of essays written by scholars based in the US and UK, primarily. A second Elphinstone conference designed for scholars based in South Asia was held in Mumbai in April 2017.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Readers can be on the lookout for a published volume of the Mumbai conference proceedings, and future installments in an integrated series of activities forming the Elphinstone Project. My wife Mar tie had the great idea of an Elphinstone conference. I thank her for that inspiration, and so much more.

CONTRIBUTORS

William Dalrymple wrote the highly acclaimed bestseller In Xanadu when he was just twenty-two. Since then, he has had seven more books published and won numerous awards for his writing, including the Sunday Times Young British Writer of the Year Award, the Duff Cooper Memorial Award, the Hemingway Prize and the Ryszard Kapuscinski Award for Literary Reportage. He lives with his wife and three children on a farm outside Delhi. His next book, The Anarchy: How a Corporation Replaced the Mughal Empire, 1756–1803, will be published by Bloomsbury in 2019.

Shah Mahmoud Hanifi is Professor of History at James Madison University where he teaches courses on the Middle East and South Asia. Hanifi’s research and publications have addressed subjects including colonial political economy, the Pashto language, photography, cartography, animal and environmental studies, and Orientalism in Afghanistan.

M. Jamil Hanifi is Adjunct Professor of Anthropology at Michigan State University. His PhD in anthropology is from Southern Illinois UniversityCarbondale and his MA and BSc in political science from MSU. Hanifi has conducted ethnographic research in Afghanistan, Pakistan, the Philippines and Tajikistan. He has written numerous publications about the ethnology of Afghanistan and the surrounding regions.

Jonathan Lee is an independent British social historian with extensive experience of Afghanistan and the surrounding regions. He has published numerous articles and books on Afghanistan’s history and archaeology. He was Fellow of the British Institute of Afghan Studies

from 1977–78 and is a Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and the British Institute of Persian Studies. He currently lives in New Zealand.

Zak Leonard is a PhD candidate in the history department at the University of Chicago. Aside from studying borderland ethnographic production and conceptualizations of ‘Muslim fanaticism’, he also researches nineteenth-century India reform societies, the transregional networks that sustained them, and the alternative forms of liberal imperialism for which they advocated.

Senzil Nawid has degrees from Kabul University, the University of Denver and the University of Arizona. She has published widely on Afghan history and culture and has conducted research in Afghanistan, the United Kingdom, France, India and Pakistan. Her major work, Religious Response to Social Change in Afghanistan, is also published in Persian.

Brian Spooner is Professor of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania. His degrees are from the University of Oxford and he has done ethnographic research in Afghanistan, India, Iran, Pakistan and Tajikistan. He has published over 100 books and articles on the ethnography, history and languages of these countries, and on globalisation.

History professor at Stockton University, Galloway, New Jersey, Robert Nichols has written or edited Land, Law and Society in the Peshawar Valley, 1500–1900 (Oxford University Press, 2001; second edition 2017), A History of Pashtun Migration, 1775–2006 (Oxford University Press, 2008), The Frontier Crimes Regulation: A History in Documents (Oxford, University Press 2013), and Colonial Reports on Pakistan’s Frontier Tribal Areas (Oxford University Press, 2005).

Lynn Zastoupil is Professor of History at Rhodes College. His research engages the intellectual encounters occasioned by British imperialism, especially in India. His books include John Stuart Mill and India (Stanford University Press, 1994), Rammohun Roy and the Making of Victorian Britain (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), and (co-edited with Martin Moir) The Great Indian Education Debate: Documents Relating to the Orientalist-Anglicist Controversy, 1781–1843 (Curzon, 1999).

Spencer A. Leonard is an independent scholar of South Asian history and anti-imperialism. His work has appeared in The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History and English Historical Studies. He is currently editing two volumes of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’s journalism on the subject of imperialism.

Kyle Gardner is a historian of South Asia with broad interests in environmental history, geopolitics, and border-making in the Himalayas. He received his PhD from the University of Chicago in 2018.

Thomas Simpson is a Research Fellow at Gonville and Caius College, University of Cambridge. He is currently completing a book on the significance of the frontier in nineteenth-century British India. He has also published on other research interests, including the history of field sciences, especially anthropology and cartography, and on mountains as spaces of modernity.

Martin J. Bayly is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the International Relations Department within the London School of Economics and Political Science. His research concerns empire, historical International Relations, and South Asia. He is the author of Taming the Imperial Imagination: Colonial Knowledge, International Relations, and the Anglo-Afghan Encounter (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Timothy Nunan is a scholar of international and global history. His work focuses on the history of Russia and Eurasia in an international context. He is the author of Humanitarian Invasion: Global Development in Cold War Afghanistan (Cambridge University Press, 2016) and is currently writing a history of socialism and Islamism in the Cold War.

Elisabeth Leake is Lecturer in International History at the University of Leeds. Her research explores the intersections between twentiethcentury South Asia, decolonization, and the global Cold War. Her first book was The Defiant Border:The Afghan-Pakistan Borderlands in the Era of Decolonization, 1936–65 (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1. The Honorable Mountstuart Elphinstone, 1779–1859.

2. Mountstuar t Elphinstone Statue in St. Paul’s Cathedral, London.

3. Mountstuar t Elphinstone Bust in Bhau Daji Lad Mumbai City Museum.

4. Marathi Students at Elphinstone College, c. 1873.

5. Parsi Students at Elphinstone College, c. 1873.

6. Mountstuar t Elphinstone’s Map of the Kingdom of Caubul, 1815.

7. The Official Sur veyor Lt. John Macartney’s Archived Map from the Elphinstone Mission to Kabul-Peshawar, 1809.

8. John Macdonald Kinneir’s Map of the Countries between the Euphrates and Indus.

9. John Arrowsmith’s Map of Asia, 1801.

10. Alexander Bur nes’ Map of Central Asia, 1834.

11. James Rennell’s Map of Hindoostan (1804).

12. Elphinstone’s Map of Caubul on a Reduced Scale.

13. Macar tney Map Legend.

14. Macar tney Map Insignia.

15. The Frontispiece to An Account: A High Ranking Minister of Shah Shuja in Official Dress.

16. The Buddhist Tope Elphinstone First Thought to be a Greek Structure.

17. Afghanistan’s northern frontier showing the border as drawn on Macartney’s unpublished map (1809), Elphinstone’s published map (1815) and the present international frontie.

18. Detail of R. Vaugondi, ‘Presqu’ Isle des Indes Orientales’ (1758), showing ‘Lake Chemay’ as the source of the Brahmaputra.

19. A page from Alexander Mackenzie’s 1884 reprint of Captain Welsh’s 1794 letter to Edward Hay, with David Scott’s notes in the right-hand column.

20. Detail of Richard Wilcox’s 1832 ‘Map … Shewing the Sources of the Irawadi river and the Eastern branches of the Brahmaputra’, identifying the Tsangpo and ‘M. Klaproth’s River’ as separate entities.

21. Tom La Touche, ‘Monument to David Scott in Cherrapunji’ following earthquake damage, 1897.

PREFACE

A NEW SOURCE FOR THE ELPHINSTONE MISSION

William Dalrymple

At around the time the Elphinstone Mission was setting off for Afghanistan from Delhi, William Hickey was in Calcutta writing in his diaries about the excesses he saw around him every day in the taverns and dining rooms of the city. He depicts a grasping, jaded, philistine world where bored, over-paid ‘Writers’ (as the Company called its clerks) would amuse themselves in Calcutta punch houses by throwing half-eaten chickens across the tables. Their womenfolk tended to throw only bread and pastry (and that, he said, only after a little cherry brandy), and this restraint was regarded as the highest ‘refinement of wit and breeding’. Worse still was ‘the barbarous [Calcutta] custom of pelleting [one’s dining companions], with little balls of bread, made like pills, which was even practised by the fair sex. … Mr. Daniel Barwell was such a proficient that he could at the distance of three or four yards snuff a candle, and that several times successively.’1

There were, however, exceptions: and the two most famous new recruits to the Company’s service, both renowned for their scholarship and application, were Mountstuart Elphinstone and William Fraser. The two young men had much in common. Both were Scots, from landed

families that had fallen on hard times. Both had come out to India at sixteen and risen fast in the Company ranks. By 1809 when the Mission was sent off to the Kingdom of Kabul, Elphinstone was twenty-nine and William Fraser was twenty-four. In that time, both had worked hard, especially at Indian languages, and both had been fast promoted over their peers to hold in their twenties remarkably important positions in the Company hierarchy. But they were rivals, very different in their personal styles, and were destined never to be friends.

Elphinstone was a lowland Scot, who in his youth had been a notable francophile. He had grown up alongside French prisoners of war in Edinburgh Castle, of which his father was governor, and there he had learned their revolutionary songs and had grown his curly golden hair down his back in the Jacobin style to show his sympathy with their ideals.2

Sent off to India at the unusually young age of fourteen to keep him out of trouble, he had learned good Persian, Sanskrit and Hindustani, and soon turned into an ambitious diplomat and a voracious historian and scholar.

Elphinstone’s own travelling diaries in the British Library give a wonderful insight to his preferred style of travel. Along with his friend Edward Strachey, Elphinstone had been appointed to the Residency in Pune in 1800, and they took their time about it, zig-zagging across almost the whole of India and spending nearly a year en route. They travelled in great state with a sawaree of eight elephants, eleven camels, four horses and ten bullocks, not to mention the horses and ponies of their servants, of whom there were between 150 and 200, together with an escort of twenty sepoys and, later, what Elphinstone described as ‘a Mahratta condottiere of 30 to 40 men’. One elephant was reserved entirely for carrying their books, including a history of the Bengal Mutiny by Edward’s father, Henry Strachey, as well as volumes on the Persian poets, Homer, Horace, Hesiod, Herodotus, Theocritus, Sappho, Plato, Beowulf, Machiavelli, Voltaire, Horace Walpole, Dryden, Bacon, Boswell and Thomas Jefferson. As they ambled across India at the Company’s expense, they read aloud to each other, sketched, practiced their Persian and Mahratti grammar, went shooting and, at night, played the flute by the light of the moon.

Since then Elphinstone had fought alongside Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington, in his central Indian Maratha wars and had

long since given up his more egalitarian ideals: ‘As the court of Kabul was known to be haughty, and supposed to entertain a mean opinion of European nations,’ he wrote, ‘it was determined that the mission should be in a style of great magnificence.’

William Fraser had also taken his time heading in a similar manner to his position as assistant to Sir David Ochterlony at the newly opened Delhi Residency, but in his youth his style was more swashbuckling than Elphinstone.

In 1805 Fraser had just won the Gold Medal at the Company’s new Fort William College, and arrived in Delhi on 5 January 1806, after a perilous journey overland from Allahabad. ‘On the road I passed several parties of armed men whom I knew to be plunderers,’ William later wrote to his father:

I always passed any who I met at a very quick pace … They generally keep about 100 yards [away] and fire with their matchlocks and are so expert that your only chance is in moving about to avoid their fire or riding straight upon them with your pistol. I talk of them when mounted; footmen robbers never show themselves but fire from some ambush.3

His close friend, the French botanist Victor Jacquemont later remarked:

[Fraser is] half-asiatick in his habits, but in other respects a Scotch Highlander, and an excellent man with great originality of thought, a metaphysician to boot, and enjoying the best possible reputation of being a country bear … This man, who is generally regarded as a misanthrope though everybody in India does justice to his great qualities and talents, I found the most sociable of men. He is a thinker who finds nothing but solitude in that exchange of words without ideas which is dignified by the name of conversation in the society of this land, so he rarely frequents it.

For my part, the only thing I find odd about him is a perfect monomania for fighting. Whenever there is a war anywhere he throws up his judicial functions and goes off to it. He is always the leader in an attack, in which capacity he has earned two fine sabre cuts on the arms, a wound in the back from a pike, and an arrow in the neck which almost killed him. This is the price he has paid for always extricating himself from the frays into which he has rushed without being forced to kill a single man; to me that was the finest thing in his whole story—that and his humaneness. To him the most pleasurable emotion is that aroused

by danger: such is the explanation of what people call his madness. It goes without saying that possessing this type of courage, M Fraser is the most pacific of men. In spite of his great black beard you would take him as a Quaker …

What makes him such a desirable companion is that he is a man of superior intelligence, yet his mode of life has made him more familiar, perhaps, than any other European with the customs and ideas of the native inhabitants. He has, I think, a real and profound understanding of their inner life, such as is possessed by few others. Hindustani and Persian are like his own mother tongue … He is an original who really should be exhibited for a fee, but is a very good fellow, whom I love as I do none of his other fellow-countrymen … If I were to describe all his eccentricities I should never come to the end of them, but he is a profound thinker withal.4

When Fraser finally arrived, ‘six months and a day after leaving Calcutta’ in time to ‘breakfast with Ochterlony’ in the new Residency, he was astounded by what he saw, and the scholarly side of his character soon reasserted itself. ‘The ruins of dynasty after dynasty lay scattered for thirty miles across the plain,’ he wrote:

The immense extent of ruins which appear all around offer a melancholy picture of the former opulence and population of the city … Archways, porticoes and gateways are all reduced to heap of desolation … I wish to ascertain historically the account of every remarkable place or monument of antiquity, or building erected in commemoration of singular acts of whatever nature.5

In pur suit of this quest, William soon began searching out the scholars and poets of the city, and before long gained a reputation for ‘consorting with the grey beards of Delhi’ whom Jacquemont described as being ‘almost all Mussulmauns of Mogul extraction, the wreck of the nobility of that court’.6 As William wrote home to his parents on 8 February 1806, in his first letter describing Delhi:

My time is now spent very pleasantly and … my situation is as desirable as any one I could hold, nor should I care if I lived here during the whole period of my sojournment in India … The business of my situation generally takes up five hours a day. [Afterwards] I read and study with pleasure the languages. They are the chief source of my amusement, [although] Delhi affords much [other] food besides. Learned natives there are a few, and in poverty, but those I have met with are real treasures. I am also making a good collection of oriental manuscripts.7

PREFACE

Among these ‘learned natives’ with whom Fraser became intimate were Shah ‘abd al-Aziz of the Madrasa I-Rahimiyya, with whom he read Persian, and Mufti Sadr al-Din Azurda, who held weekly poetic mushairas and who later became an important figure in the Delhi College. William was also close to the poet Ghalib, who later wrote that when Fraser died, he ‘felt afresh the grief of a father’s death.’8

Slowly, William changed out of all recognition from the callow youth who had left Calcutta. He pruned his moustaches in the Rajput manner and according to one traveller, fathered ‘as many children as the King of Persia … Hindus and Muslims according to the religion and caste of their mamas, and are shepherds, peasants, mountaineers according to the occupation of their mother’s family’ from his harem of ‘six or seven legitimate [Indian] wives’ who ‘all live together some fifty leagues from Delhi’.9

When the for midable Lady Maria Nugent, wife of the new British commander-in-chief in India, visited Delhi she was horrified by what she saw there. It was not just Ochterlony that had ‘gone native’, she reported; his assistants Fraser and Edward Gardner were even worse, as she wrote in her journal:

I shall now say a few words of Messrs. Gardner and Fraser who are still of our party … They both wear immense whiskers, and neither will eat beef or pork, being as much Hindoos as Christians, if not more; they are both of them clever and intelligent, but eccentric; and, having come to this country early, they have formed opinions and prejudices, that make them almost natives. In our conversations together, I endeavour to insinuate every thing that I think will have any weight with them. I talk of the religion they were brought up in, and of their friends, who would be astonished and shocked at their whiskers, beards, &c. &c. All this we generally debated between us, and I still hope they will think of it.10

Often on the move, and living under canvass, he grew into a great bear of a man, brilliant but wild and uncontrollable. William Gardner, put it succinctly: ‘Fraser is a sukht banchod, [a right sister-fucker] … such an obstinate fellow … They mean to do something with him [i.e. promote him] but he is of such unbending stuff that he would refuse everything.’11

In 1809 when Lord Minto decided to send off a mission to Afghanistan to seek allies against a possible Napoleonic thrust against

India, Fraser volunteered. His brother Aleck immediately noted the obvious similarity between the two ambitious and successful young Company Orientalists who would lead the expedition, one from the Lowlands of Scotland, the other a Highlander:

I have no doubt of William being particularly distinguished by Elphinstone, as their qualities and dispositions are precisely similar, both being bold dashing characters with acute powers of mind, well fitted for conducting a negociation with a powerful, independent, and barbarous nation … I need not say anything of Elphinstone as he is precisely William in, I believe, all points.12

Fraser’s previously unpublished letters from the Embassy are an important new source for the Elphinstone Mission, which up to now has always been judged solely from Elphinstone’s own celebrated account of it. To this, William Fraser gives an important counterpoint.

The first Embassy to Afghanistan by a western power left the Company’s Delhi Residency on 13 October 1808, with the ambassador accompanied by 200 cavalry, 4000 infantry, a dozen elephants and no fewer than 600 camels. Accompanying Elphinstone were a secretary, two assistants, one of which was William, a surgeon, two surveyors and eight officers in charge of the escort. The colourful, chaotic column of elephants, camels, horses and men stretched for 2 miles.

Once embarked on the long trek, William had hoped to write to his brother Aleck daily, but as they normally made camp late at night after an early morning start, he had ‘neither the means, nor the power of writing to anyone’. However, he told Aleck he was writing a daily journal but ‘you must never expect very accurate or detailed accounts, in long flowing sentences, and finely tuned periods’. Even when they stopped for a few days, William’s writing was constantly interrupted and the postal system, the dawk or dak, was not secure, and the further they travelled the more it deteriorated. One packet for William was stuffed with straw, the next was torn to pieces and in the third there was only ‘the envelope of a letter … the dawks are constantly rifled and nothing now is safe’. Despite all these hazards, Aleck received around sixty letters from William during the year or so of the expedition.

When Shah Shuja heard of the approach of the Embassy he knew what to do: ‘We appointed servants of the royal court known for their refinement and good manners to go to meet them,’ he wrote later in