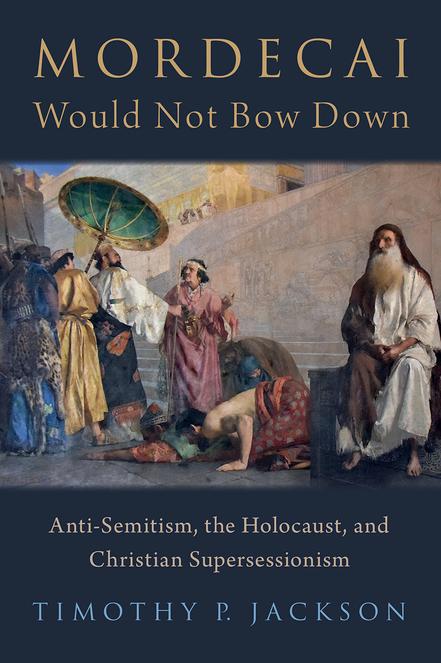

Mordecai Would Not

Bow Down

Anti-Semitism, the Holocaust, and Christian Supersessionism

TIMOTHY P. JACKSON

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Jackson, Timothy P. (Timothy Patrick), author. Title: Mordecai would not bow down : anti-Semitism, the Holocaust, and Christian supersessionism / Timothy P. Jackson. Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Contents: Prayerful Unscientific Preface—Judaic Holiness and a Holistic Approach to Anti-Semitism and the Holocaust—Legitimating a Topic as Old as Esther—The Perennial Either/Or—Nazism and the Western Conscience—The Evils of Supersessionism—Jesus and the Jews: Two Suffering Servants Incarnate—Naming Good and Evil: Hitler’s Insidious Genius—A Closer Look at Schadenfreude and the Prophetic—Conclusion: Guilt, Innocence, and Anne Frank. Identifiers: LCCN 2020051803 (print) | LCCN 2020051804 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197538050 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197538067 (updf) | ISBN 9780197538081 (oso) | ISBN 9780197538074 (epub) Subjects: LCSH: Christianity and antisemitism. | Holocaust (Christian theology) | Jews—Election, Doctrine of. | Christianity and other religions—Judaism. | Judaism—Relations—Christianity. Classification: LCC B M535.J33 2021 (print) | LCC B M535 (ebook) | DDC 261.2/6—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020051803

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020051804

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197538050.001.0001

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Integrated Books International, United States of America

This book is dedicated to Harold Bloom (RIP) and to the eleven murder victims of the October 27, 2018, synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Human nature being anxious and despairing as it is, antiSemitism will always be with us in history. God being who God is, philoSemitism will also ever be temporally real. But may the Jews teach us the crucial distinction between time and eternity, and between “I want” and “I love.” Seventy-six years after the liberation of Auschwitz, let divine grace move us to enact the Good—for the Holocaust’s six-million-plus, and for the world.

When Haman saw that Mordecai would not bow down or do obeisance to him, Haman was infuriated. But he thought it beneath him to lay hands on Mordecai alone. So, having been told who Mordecai’s people were, Haman plotted to destroy all the Jews, the people of Mordecai, throughout the whole kingdom of Ahasuerus.

Esther 3:5–6

Here is my servant, whom I uphold, my chosen, in whom my soul delights; I have put my spirit upon him; he will bring forth justice to the nations.

Isaiah 42:1

The Jewish doctrine of Marxism rejects the aristocratic principle of Nature and replaces the eternal privilege of power and strength by the mass of numbers and their dead weight. Thus it denies the value of personality in man, contests the significance of nationality and race, and thereby withdraws from humanity the premise of its existence and its culture.

Adolf Hitler1

The liberation [of Germany] requires more than diligence; to become free requires pride, will, spite, hate, hate, and once again, hate.

Adolf Hitler2

“You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.” This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: “You shall love your neighbor

1 Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, trans. Ralph Manheim (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1943), p. 65.

2 Adolf Hitler, Adolf Hitler spricht: Ein Lexicon des Nationalsozialismus (Leipzig: R. Kittler Verlag, 1934), p. 23, quoted by Richard Weikart in Hitler’s Religion: The Twisted Beliefs That Drove the Third Reich (Washington, DC: Regnery History, 2016), p. 370.

as yourself.” On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.

Matthew 22:37–40

For those who live according to the flesh set their minds on the things of the flesh, but those who live according to the Spirit set their minds on the things of the Spirit. To set the mind on the flesh is death, but to set the mind on the Spirit is life and peace.

Romans 8:5–6

The Jews have a special duty to save G-d in the world.

Leonard Cohen3

3 “Leonard Cohen speaks about G-d consciousness and Judaism (1964),” a YouTube video accessed on November 21, 2017, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cFMm_x1qlPY. In the balance of this essay, I will sometimes refer to “God,” even when discussing Jewish piety, but the devout reader might substitute either “Adonai” (“The Lord”) or “HaShem” (“The Name”), as I do in places.

Prayerful

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

Prayerful Unscientific Preface

Moriah to Sinai to Calvary . . . Abraham to Moses to Jesus . . . never before had the rights of Nature been so profoundly violated, and good and evil would never be the same. Instead of gods goading humans to infanticide, aggressive war, and other forms of hate-filled bloodletting—a picture common to many (if not most) ancient religions4 one God, one people, and one person gradually emerged and struggled to call humanity to love, justice, and protection of the weak and vulnerable. It was and is a slow and fitful process, and the people and person calling are not without anticipations in world history. But they are remarkably long-lived and distinctly inspiring as well as threatening. This book examines the ideal embodiment of moral monotheism by the Jews (including Jesus of Nazareth) and the violent resistance to their call, especially in the form of the Nazi Holocaust and Christian supersessionism. Walter Burkert observes: “The Hebrew Bible is full of atrocities committed against . . . other tribes and cults in the name of Yahweh. Christianity has taken strength and enormous propaganda from the persecutions by pagan Rome but started its own persecution of pagans and more still of heretics and Jews as soon as it came to power.”5 I do not deny for an instant, then, that Judaism and Christianity have often propagated hate and hostility toward others, but I read both traditions as, at their best, striving to overcome their own vicious past and present in the name of God’s mercy and holiness. It was during a 2008 visit to Babi Yar, the ravine outside of Kiev in the Ukraine where some 33,771 Jews were shot during the last two days of September 1941, that I first suspected that anti-Semitism is fundamentally due to hatred of God and of those whom God loves—especially the frail and defenseless. The symbolism of the mass murders being timed by the Einsatzgruppen to coincide with the eve of Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, pointed to a truth so obvious as to be easily overlooked. The more I read and reread Mein Kampf and other Nazi documents, however,

4 See The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Violence, ed. Mark Juergensmeyer, Margo Kitts, and Michael Jerryson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

5 Burkert, “A Problem in Ancient Religions,” in ibid., p. 438.

the more evident it became that the horrendous criminality of the Holocaust was not merely absurd but largely driven by pagan ideology. The final piece of the puzzle was the recognition that all of us have an inner Nazi that resents a supernatural faith that challenges our natural desires and temporal loyalties. We want Mordecai to bow down to our idols and our selves, and Yom Kippur’s repentance and atonement before a righteous Creator are offensive to us haughty creatures. So the Jews must be “put away” lest they remind us of who we are: mortal and sinful. Or so the logic of anti-Semitism supposes, however subliminally.

Any text that, like this one, would measure the palpable wickedness of humanity against the transcendent goodness of the biblical God must come to grips with Isaiah 55:8–9:

For my thoughts are not your thoughts, nor are your ways my ways, says the lord. For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways and my thoughts than your thoughts.

These words counsel epistemic humility, but not despair. Even dour Jeremiah declares: “[The Lord] will give you shepherds after my own heart, who will feed you with knowledge and understanding.” Pace some commentators, the abomination of the Holocaust is not simply beyond all ethical and theological analysis, but such analysis cannot proceed like a detached narrative or a seamless deductive argument. Hatred of the Jews and the related Shoah are shocking, ad hoc, and emotive, and so, too, to some degree are my explanations of them that follow. My pages are also products of intellect and will, of course, and I dedicate my Introduction and Chapters 1 and 2 to placing the issue of anti-Semitism in a broad conceptual and historical context and to defending my holistic approach. The unfolding chapters are, however, more like flashes of light and meshed intuitions than like a list of empirical facts or a series of logical propositions. I try to present my claims coherently and to back them up with evidence and argument, but the process is more like painting a picture than like writing an equation. As one of the main instruments of the Holocaust, schadenfreude must be shown and felt as a sin; it cannot merely be outlined or abstracted as a syndrome. The prophetic, the contradictory and corrective of schadenfreude, is similarly striking and mysterious. Neither evil nor good can be captured in a closed

scientific system, but to think that we are consigned to silence before horrific animosity and desecration, others’ and our own, is to be guilty of bystanding. When the human mind and heart reach their limits, there is still the possibility of insight and action powered by God’s grace.

To maintain, as I do, that instinctive rejection of moral monotheism, in favor of survival of the fittest, was a key reason for the Holocaust is not to say that the Nazis were always aware of or candid about their own idolatry. Nor is it to deny that there are typically multiple causes at work in anti-Semitism: religious, ethical, aesthetic, political, economic, and/or biological. I focus on a primary overarching ingredient in anti-Judaic malice—natural resentment of supernatural faith and judgment—but I try studiously to avoid reductionism or false certitude.6 This book is dedicated to Harold Bloom (RIP) and to the eleven murder victims of the October 27, 2018, synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The Pittsburgh killings and the still more recent homicides in the kosher market in Jersey City, New Jersey, illustrate the sad fact that hatred of the Jews (and of God) has myriad motives, yet there is “method” to it even when it seems quite “mad.” Note, just so, the explicit connection between anti-Semitism in the Jersey City case and a despising of the police and of law and order. Mosaic Torah and Christian Gospel7 remain two aspects of the one thing needful—the divine law of love—but we rebel against it every day. The Nature-god of the Nazis is us writ large: greedy, jealous, cruel, violent, and most of all anxious and afraid. Ultimately, a critical encounter with genocidal hatred, however interdisciplinary, must become a prayer of repentance and a prophetic call to reform.

6 Though far from a moral skeptic, Aristotle reminds us that “it is the mark of an educated man to look for precision in each class of things just so far as the nature of the subject admits.” See his The Nicomachean Ethics, trans. David Ross (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980), Book I, Chapter 3, 1094b25, p. 3.

7 By “Mosaic Torah,” I mean more that the first five books of the Hebrew Bible; by “Christian Gospel,” I mean more that the first four books of the New Testament. I concentrate in what follows on the written scriptures of Judaism and Christianity, but I am aware, as Adin Steinsaltz has observed, that: “The sages believed it was the oral law—the Mishnah and the Talmud—that rendered the Jewish people unique.” (See Steinsaltz, The Essential Talmud, trans. Chaya Galai (New York: Basic Books, 2006), p. 102.) In its broadest sense, “Torah” refers to the whole of Jewish thought and practice, even as “Gospel” refers to the entirety of the Christian ethos and ethic. They are intimately connected, however, both being eternity entering time, the projected heart and mind of G-d.

Acknowledgments

I owe a profound debt of gratitude to the many people who have offered critical feedback on all or part of this monograph: Ira Bedzow, David Blumenthal, Iris Bruce, Bryan Ellrod, Andrew Ertzberger, John Fahey, Robert Franklin, Lenn Goodman, Eric Gregory, Jon Gunnemann, Jennifer Herdt, Brooks Holifield, Carl Holladay, Kevin Jackson, Joel LeMon, Deborah Lipstadt, Walter Lowe, Gilbert Meilaender, Brendan Murphy, Carol Newsom, Edmund Santurri, Ted Smith, Jonathan Strom, Steven Tipton, Richard Weikart, William Werpehowski, John Witte, Jacob Wright, and the students in several iterations of my class on “Christianity and the Holocaust” at The Candler School of Theology at Emory University.

From June 18 to 22 of 2012, I was fortunate to participate in a seminar on “Understanding Complicity: The Churches’ Role in Nazi Germany” at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. I thank Victoria Barnett and Robert P. Ericksen for their expert leadership of the sessions; it was there that some of the ideas for this book began to germinate.

I would also like to thank Leslie Gordon, Executive Director of the William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum in Atlanta, Georgia; Rabbi Joseph Prass, Executive Director of the Weinberg Center for Holocaust Education at the Breman; Michelle Langer, Holocaust Speaker Coordinator at the Breman; and Jennifer Reid, Director of Volunteer and Visitor Services at the Breman. At a 2019 Summer Institute at the museum, I was edified by a number of first-rate scholars of the Holocaust. I was also privileged to listen to and speak with four Shoah survivors: Bebe Forehand, Robert Ratonyi, Hershel Greenblat, and Tosia Schneider (RIP). Two other survivors, Murray Lynn (RIP) and George Rishfeld, addressed me and my Emory students on different occasions. The witness of these six stalwart souls was and is a constant inspiration.

Finally, I would like to express my appreciation to the superb professionals at Oxford University Press: Editors Drew Anderla, Zara CannonMohammed, Hannah Kinney-Kobre, and Cynthia Read; and Project Manager Haripriya Ravichandran. Without the patient assistance of all of these individuals, this manuscript would never have come forth.

Introduction

Judaic Holiness and a Holistic Approach to Anti-Semitism and the Holocaust Original Sin and Nazism as Radical Evil

In 1821, Heinrich Heine famously wrote, “Where one burns books, in the end one also burns human beings.”1 This quote is often (and rightly) cited as an oracular anticipation of the Nazi Holocaust, which began in part with the burning of printed works by Jews, communists, and others judged subhuman or threatening. It is seldom (if ever) noted that Heine’s coupling of book burning and people burning can also be reversed and expanded in the case of the Jews and the Third Reich. Where the Nazis incinerated Jewish people, they also committed Jewish texts, paintings, sculptures, films, buildings, and religious artifacts to the flames. Why? If, as many argue (see Chapter 1), the Nazi targeting of the Jews were simply irrational or based solely on the Jews’ supposed racial inferiority (genes), then there would have been no need to target systematically their creedal affirmations and artistic expressions (memes). But the Nazis did feel this need and acted on it, torching the oeuvre of Heine himself, a reluctant Jewish convert to Lutheranism.

I contend in this book that Nazi anti-Semitism was significantly motivated by moral, theological, and aesthetic considerations, as well as biological ones, all these factors being intertwined. The multidimensionality of the Third Reich’s opposition to the Jews and Judaism was a Counter-Sublime2

1 The full German quote is: Das war ein Vorspiel nur, dort, wo man Bücher Verbrennt, verbrennt man auch am Ende Menschen. These lines appear in Heine’s play Almansor (Berlin: Hofenberg, 2015), German edition, p. 11. The partial translation is my own.

2 I take this word and its basic meaning from Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973), pp. 15 and 99–112.

Mordecai Would Not Bow Down. Timothy P. Jackson, Oxford University Press. © Oxford University Press 2021. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197538050.003.0001

dictated in part by Judaic holiness itself. A single representative quote from Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf sets the stage for my holistic approach:

The Jewish doctrine of Marxism rejects the aristocratic principle of Nature and replaces the eternal privilege of power and strength by the mass of numbers and their dead weight. Thus it denies the value of personality in man, contests the significance of nationality and race, and thereby withdraws from humanity the premise of its existence and its culture.3

I attribute this rejection of Judaism as unnatural and anticultural to what I call “original sin”: the natural proclivity to elevate self by denigrating others, especially those who traditionally stand for supernatural goodness. Anxious over our own finitude and mortality, we abuse or neglect our neighbors to try to guarantee our power or at least to distract ourselves from our lack of real power. We sometimes kill other people in order to avoid being killed by them, but we also kill others in order to try to master mortality, to slay death itself by objectifying it in enemies. In short, the quest for domination and even genocide is an upshot of dread over our limitedness and vulnerability.4 Moses and the Hebrew Scriptures diagnose and obstruct this self-involved and self-deceptive process.5

Moses’s vision of the Burning Bush (Exodus 3:1–15) founded a revelation of divine order and purpose for the world: the Sacred Name, a set of Ten Commandments (Exodus 20:1–17), and an associated way of life. The hallmark of that ethos was a holiness that emulates the steadfast love (’hesed) of the Creator by caring for all “neighbors,” especially the widow and the orphan and others who are weak and vulnerable (Leviticus 19:18, Leviticus 19:34, Exodus 22:21–23, and Deuteronomy 10:18). Admittedly, the full emergence of universal love and suffering service to the world as Judaic ideals was as gradual and fraught as their emergence in the life and teaching of Jesus. Even Jesus lapses into invidious “us” versus “them” contrasts, as in his conversation with the

3 Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, trans. Ralph Manheim (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1943), p. 65.

4 See Søren Kierkegaard (Vigilius Haufniensis), The Concept of Anxiety, trans. Reidar Thomte in collaboration with Albert B. Anderson (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1980).

5 Paul Ramsey writes, “The connection between dread of death and sin, made prominent in Christian consciousness, was nowhere better stated than in Ecclesiastes: ‘This is the root of the evil in all that happens under the sun, that one fate comes to all. Therefore, men’s minds are filled with evil and there is madness in their hearts while they live, for they know that afterward—they are off to the dead!’ ” See Paul Ramsey, “The Indignity of ‘Death with Dignity’,” in On Moral Medicine” Theological Perspectives in Medical Ethics, 3rd ed., ed. M. Therese Lysaught and Joseph J. Kotva Jr. with Stephen E. Lammers and Allen Verhey (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2012), p. 1050.

Canaanite woman (Matthew 15:21–28), and he embraces his Passion only with some ambivalence (see Matthew 26:36–44). Nevertheless, the revolutionary commitment to “the Other” and “the other” is a spiritual trajectory discernible in both “the chosen people” (Deuteronomy 14:2) and “the Son” (Mark 10:45). In the Jews, God uses a tribe to overcome tribalism; in Jesus, God uses an individual to overcome individualism. This does not mean that tribes and individuals are evil or illusory. There can be no humanity without just social relations, even as the individual bears the image of God and thus is an irreducible locus of value. Rather, Judaism and Christianity combine to illustrate, respectively, how to avoid making idols of ethnicity and personality; hence, they both anticipate and transcend modern communitarianism and liberalism.6 In turn, the Holocaust and Christ’s Passion are not two unrelated, redundant, or (Heaven help us!) antithetical crucifixions. Rather, they are consanguineous Suffering Servants acting and being acted on in history, eternal Holiness translated into time to address humanity’s specific needs and potentials (see Chapter 5).

To this day, the Torah and its moral monotheism remain at the heart of Jewish culture and are a “light to the nations” (Isaiah 49:6). That light, intended to illumine the transcendental Good and to overcome earthly sin via divine grace, is opposed and perverted, however. It confronts a profane vision that rejects the atoning solidarity of Yom Kippur and its reminder that everybody dies, and that seeks instead to visit death on “the other” in the name of “natural law” and “survival of the fittest.” Such naturalism reached its abominable zenith, or should I say nadir, in the ovens of Auschwitz. The burden of my text is to explain (Nazi) anti-Semitism and the Holocaust without seeming to justify them. Judaism is no more culpable or causally responsible for Nazism than the Mosaic Law is culpable or causally responsible for sin (cf. Romans 7:7–13), even though sin must be diagnosed and treated in terms of the Law. I attempt such a diagnosis and treatment mainly by examining the model of Mordecai in the book of Esther and by unpacking two related forms of moral turpitude: schadenfreude and Christian supersessionism. The tendency to find joy in others’ suffering and the insistence that one’s own holy writ must supplant and even falsify all other testaments are two major

6 The communitarian goods of tradition and solidarity, together with the liberal goods of equality and freedom, are affirmed in both biblical creeds yet subordinated to faith, hope, and love. Human community and personal autonomy are trumped by theonomy and the holy love of all neighbors. Such love bestows worth, rather than appraising it. See my Political Agape: Christian Love and Liberal Democracy (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2015). I take the language of “bestowal” and “appraisal” from Irving Singer, The Nature of Love, Vols. 1-3 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1966, 1984, 1987).

sources of the Shoah. The model of Jesus is also crucial to understanding and overcoming anti-Semitism but precisely because he (like Mordecai) is a manifestation of Torah.

If I am correct, every Jew who was interred in a Nazi death camp was a prisoner of conscience, even as every Jew who was murdered by the Nazis was a martyr. This is so because it was Jewish conscience and Jewish faith themselves that the Nazis loathed and wished to eliminate by degrading and finally destroying the Jewish people. Again, I do not ignore the complexity of the supposedly genetic factor in Third Reich and other forms of anti-Semitism, but I argue that the pantheistic naturalism at the core of National Socialism inevitably conflicted with Jewish moral monotheism. The erotic and eudaimonistic mind does not relish being dependent upon and decentered by God’s righteousness (tsedaqah). If we insist that the Holocaust was pure insanity or absurdity without any objective basis, then we fail to appreciate its radical evil. If we blind ourselves to how Christian Scriptures helped make the genocide possible (if not inevitable), then we both let “the Church” off too easily and make it more likely that the Shoah will be repeated. This is not to blame the victims but to name the victimizers: our instinctually prideful selves.

Human Nature, Moral Monotheism, and Divine Fire

Human nature leans toward self-deception, but, happily, that nature is composite and dialectical: there is another side to us beyond the finite and material. The biblical tradition typically conceives of humanity as a psychosomatic unity, a combination of soul and body, but this conception has been elaborated in various (yet related) ways. In Genesis 2:7, Moses recounts how “the lord God formed man [adam] from the dust of the ground [adamah], and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life,” thus making him “a living being [nephesh].” Saint Augustine refers to a human being as “animated earth [terra animata],”7 whereas Søren Kierkegaard describes “the self” as “spirit”: “a synthesis of the infinite and the finite, of the temporal and the eternal, of freedom and necessity.”8 It is Kierkegaard’s anthropology that I primarily draw on in

7 “Terra animata” can also be rendered as “dust with a soul.” See Augustine, City of God, trans. Henry Bettenson (New York: Penguin Books, 1984), Book XIII, Chapter 24, pp. 541–542.

8 Kierkegaard (Anti-Climacus), The Sickness unto Death, trans. Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1980), p. 13.

this volume. For him, the human person is self-aware and capable of making decisions that, within constraints, define and redefine one’s identity. I am not a disembodied angel unencumbered by history, but neither am I merely the blind consequence of matter in motion. More specifically, the self is both a state and an activity grounded in “the power that established it”: God.9 The bodily attributes and traits of character that I possess at any given moment are both a given product from the past and an ongoing project for the future, a function of impersonal forces, personal choices, and divine grace. As much as I might try to flee from it, the process of self-articulation with and through God is endless until death.

Kierkegaard helps us discern the rather puzzling fact that the very same human nature that often moves us to violence and aggression (“evil”) can help occasion sympathy and cooperation (“goodness”). A shared sense of weakness and fallibility can spark pity for others (and ourselves) and induce us to band together for mutual support and protection. This banding is typically limited to small tribal groups, but, in addition to inducing hostility toward “the other,” anxiety can open us to solidarity with the whole human species, a sense of being fellow sinners and fellow sufferers, creatures of the same Creator. More positively, an appreciation of the sanctity and dignity of human life—its deepest needs and potentials—can carry us beyond prudence to selfsacrificial love for God and all neighbors, a love which emulates God’s creative love for the world. As SK’s pseudonym, Vigilius Haufniensis, reminds us, anxiety is the last psychological state before the leap into sin (the refusal to be oneself) or into faith (the affirmation of self and others before God).10

9 Ibid., p. 49.

10 Kierkegaard (Vigilius Haufniensis), The Concept of Anxiety, pp. 92 and 114–115. In The Paradox of Goodness: The Strange Relationship between Virtue and Violence in Human Evolution (New York: Pantheon Books, 2019), Richard Wrangham sounds strikingly Kierkegaardian in arguing that there are compassionate and cooperative aspects of human nature together with aggressive and selfish aspects. The former constitute a proclivity to charity and sacrifice for the weak and vulnerable, while the latter tend to embrace hatred and survival of the fittest. Paradoxically, evolutionary forces have selected for both capacities, for peaceful symbiosis as well as violent competition, leaving each of us a kind of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde—capable of great benevolence and great cruelty—according to Wrangham. In this text, I maintain that Hitler and the Nazis rejected charity and championed survival of the fittest to such an extent that they embodied radical evil. Conversely, I contend that the Jews traditionally stand for ’hesed and radical goodness. It may appear, then, that my account of ethics and anthropology is in agreement with that of Professor Wrangham. This is not the case.

There is a key difference between my picture of morality and personality and his. Wrangham, a primatologist, places both charity and cruelty entirely within the realm of time and human nature; for him, human beings have “self-domesticated” via natural selection. I, a theologian, see charity as requiring the special grace of the eternal God interacting with human freedom; we are neither self-created nor self-fulfilled. Evolution itself is designed by God (not us) to be teleological and to cast up intelligence and ultimately love of God and neighbor. See my “Evolution, Agape, and the

It was Moses who, approximately 3,300 years ago,11 first formulated in the West the alternative of universal love (call it “radical goodness”) in rigorously moral and monotheistic terms.12 I readily grant that there are some precursors of these ideas in ancient Hittite religion and that, initially, some interpreted the Pentateuch to be relevant only to Israelites. Some even today read “love your neighbor” (Leviticus 19:18) as referring only to fellow Jews.13 But Leviticus 19:34 is more emphatically cosmopolitan:

Image of God: A Reply to Various Naturalists,” in Love and Christian Ethics: Tradition, Theory, and Society, ed. Frederick V. Simmons and Brian C. Sorrells (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2016); see also my “The Christian Love Ethic and Evolutionary ‘Cooperation’: The Lessons and Limits of Eudaimonism and Game Theory,” in Evolution, Games, and God, ed. Martin Nowak and Sarah Coakley (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013).

We still need a cultural history that accounts for the emergence of symbiosis and even selfsacrifice among human beings. This text is a partial contribution to that end. Here a philo-Semite tries to make sense of the ubiquity of anti-Semitism in the larger context of evolutionary forces. I believe that the Jews (a.k.a. the Suffering Servant) are the key to understanding virtue and violence culturally, even as for Wrangham bonobos are the key to understanding them biologically. Accordingly, I try to explain how ’hesed and agape were bequeathed to us by the Jews—memetically and to a degree genetically—and how such a cooperative legacy confronts, calls up, and/or recalls a Counter-Sublime based on hatred and aggression against “the other” (a.k.a. Nazism).

11 I conform to convention in attributing the first five books of the Hebrew Bible to Moses. Though probably a mythic or composite figure, he is traditionally said to have lived between circa 1400 and circa 1270 BCE, several centuries after Abraham was thought to have lived and died. Between the time of Abraham and the time of Moses, the Talmud suggests that the people were called to live according to the seven Noahide laws, given by Noah to his children.

12 Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten (ca. 1380–ca. 1336 BCE) may have been the first monotheist, but he was not a moral monotheist. Rather than teaching steadfast love for all of God’s children, he insisted on unique privilege for himself and the royal family. In fact, the Sun disk (the Aten) worshipped by Akhenaten, while singular, was apparently not the truly transcendent Deity Moses found in YHWH. (See my brief discussion of Akhenaten in Chapter 1 of this volume.) Some doubt that even Moses was a moral monotheist. In The Birth of Monotheism: The Rise and Disappearance of Yahwism (Washington, DC: Biblical Archaeological Society, 2007), André Lemaire affirms that “the divine name, the tetragrammaton (Greek for ‘four letters,’ in this cases four Hebrew consonants) ‘YHWH,’ goes back to Moses; and YHWH, at least to some extent, was brought into Canaan by the group Moses led, the Bene-Israel (Sons of Israel)” (pp. 20–21). According to Lemaire, however, “early Yahwism was not monotheistic” (p. 27). Yahweh was a national god, and Moses was a henotheist, believing in multiple deities with YHWH at the top. Lemaire contends (p. 10) that truly universal monotheism is espoused first by Deutero-Isaiah in the sixth century BCE. I believe that Lemaire overstates the contrast between henotheism and monotheism, at least in the Pentateuch, but (1) the prophet who wrote Second Isaiah was no doubt a Jew, and (2) it is sufficient for my purposes that Moses be traditionally identified with belief in one righteous Creator and Judge of the universe.

13 Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh maintains that a purely intramural love is bidden in Leviticus 19:17–18: “In the Torah, the Hebrew word reyacha explicitly means ‘your fellow Jew.’ It does not refer to anyone outside the Jewish faith. ‘Neighbor’ is not an accurate translation for the word reyacha. The Hebrew word for “neighbor” is shachen. . . . Thus the . . . verse veahavta l’reyacha kamocha, ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself,’ does not imply a universal neighbor. To be honest with the text, the parenthetical ‘a fellow Jew’ must appear.” But then the good Rabbi brings to light the crucial point: “However, the Torah requires a level of love for every one of G-d’s creations. G-d’s ultimate motivation for Creation is love. . . . The Ba’al Shem Tov teaches that a Jew must love all of Creation, as everything reflects G-d’s motivation of love.” (See “Responsa” on the Gal Einai Institute website, accessed on May 21, 2019: https://www.inner.org/responsa/leter1/resp22.htm.) As I point out, the universality of the love required by God of the Jews, even for “the alien,” is made undeniable in Leviticus 19:34.

The alien who resides with you shall be to you as the citizen among you; you shall love the alien as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt: I am the Lord your God.

I am pointing, then, to inclusive seeds that are undeniably present in a number of Hebrew Scriptures and that developed across history. Interestingly, there is an analogous but normatively reverse ambiguity with reference to Hitler and Nazism. Some scholars hold that genocidal intent toward the Jews was present and essential in the man and the movement from the beginning, while others maintain that it arose only contingently and over time. Based on my reading of Mein Kampf and other documents,14 I tend to side with the former school, but Nazism and Hitler, like Judaism and Jesus, are not static or monolithic. (Whether Hitler and Nazism were genocidal from the start is as complex and ambiguous a question as whether Moses and Yahwism were monotheistic from the start.) I trust, however, that some plausibly general points, descriptive and prescriptive, can be made about both Judaism and Nazism.

In the twentieth century, Mary Shelley’s “Modern Prometheus,” Victor Frankenstein, and his monstrous creation came to life for real in Germany. Whereas the Mosaic God of the Burning Bush warmed and enlightened without consuming, Adolf Hitler hailed Victory and took the Promethean theft of fire to its extreme (if not unavoidable) conclusion. In 1933, he used the Reichstag blaze, which the Nazis themselves probably set, as an excuse to suspend many civil liberties and to disenfranchise the Jews. In 1938, in a kind of Nazified Walpurgisnacht, paramilitary Sturmabteilung members and ordinary civilians battered and/or burned over two hundred and fifty synagogues on Kristallnacht, supposedly in retaliation for the assassination

(NB: The Ba’al Shem Tov was the founder of Hasidic Judaism in the eighteenth century; the synagogue associated with his name in Medzhybizh, Ukraine, was destroyed by the Nazis.)

14 See, for instance, “the Hitler Letter” (a.k.a., “the Gemlich Letter”) acquired by the Simon Wiesenthal Center in 2011 and displayed at the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles. Written by Adolf Hitler on September 16, 1919, roughly five years before he composed Mein Kampf, a crucial passage reads as follows: an antisemitism based on purely emotional grounds will find its ultimate expression in the form of the pogrom. An antisemitism based on reason, however, must lead to systematic legal combating and elimination of the privileges of the Jews, that which distinguishes the Jews from the other aliens who live among us (an Aliens Law). The ultimate objective [of such legislation] must, however, be the irrevocable removal of the Jews in general.

(See “Adolf Hitler: First Anti-Semitic Writing,” The Jewish Virtual Library, accessed on April 17, 2020: https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/adolf-hitler-s-first-anti-semitic-writing.)

of a Nazi diplomat by a young German-born Polish Jew. “I watched Satan fall from heaven like a flash of lightning,” Jesus told his disciples (Luke 10:18), and in 1939 Hitler replaced biblical Shalom with lightning war (blitzkrieg) against Poland and the world. He eventually sought to make a conflagration of anyone and anything that turned away from Aryan blood and toward universal Deity. The weak and the vulnerable were objects of his contempt, rather than compassion. In the Nazi state and its occupied territories, the ravenous eagle of Prometheus was reconditioned and set on Jewish prey. Monotheistic belief and believers were themselves considered base and polluted, hence to be burned away with a stunningly rational efficiency. Thus divine fire fell into its opposite.15

The Judaic Critique of Eros and the Book of Esther

The genius and offense of Jewish moral monotheism is that it demands holiness rather than happiness, revolutionizing the many traditions of erotic desire by subordinating them to the love of God.16 How often do our wants and needs make an object of “the other,” even “the Holy Other,” and erase them for our purposes. It is essential to Yahweh’s creative benevolence, in contrast, that He speaks the world, including human creatures, into existence and allows them “to be.” (Yahweh makes Hamlet’s pressing question possible

15 God is, according to Judaism, the source of radical goodness. Sinful human beings alone simply do not have the wisdom or authority to deploy (putatively) divine fire, inwardly or outwardly, whatever the cause. Lest the Nazis seem entirely anomalous, I would remind us that, in 1945, at least 100,000 Japanese civilians died in the March 9–10 firebombing of Tokyo by the American Air Force. (See The Asahi Shimbun Cultural Research Center, “The Great Tokyo Air Raid and the Bombing of Civilians in World War II,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 11-2-10, March 15, 2010.) Another 66,000 died in the August 6 atomic bombing of Hiroshima; and 39,000 in the August 9 atomic bombing of Nagasaki. (These are the lowest numbers I have found; the usual minimum of immediate deaths in Hiroshima is 75,000; in Nagasaki, 50,000; but nobody knows for sure the accurate figures.) This means that, in these three raids alone, the United States directly killed at least 205,000 Japanese citizens. These “burnt offerings” were individuals the vast majority of whom we knew to be “innocent noncombatants,” according to traditional just war theory. Of the roughly 300,000 citizens of Hiroshima, for example, only 43,000 were thought by the American military to be Japanese soldiers. (See “The Manhattan Project: An Interactive History,” U.S. Department of Energy, Office of History and Heritage Resources.) Yet we turned the whole city into what Colonel Paul Tibbets, the pilot of the Enola Gay, described as “a black boiling barrel of tar.” (See Tibbets interview first broadcast on April 4, 1974, in the episode entitled “The Bomb,” in The World at War series, produced by Thames Television.) Many, if not all, of the Japanese noncombatants may have supported the war ideologically, but they were not materially prosecuting any aggression and therefore should have been immune from direct attack by the standard conventions of war. The Allies were not genocidal, but by those conventions, all of the aforementioned killings constituted mass murder.

16 I intend here both the subjective and the objective genitive: God’s love for us and our love for God.

by proleptically answering it in the affirmative.) Moreover, He calls on us to be similarly generous in our finite and fallible way. Mirabile dictu, Judaism teaches this without vilifying natural desires but by refusing to allow them to negate the neighbor and divinize the self. This is the difference that makes all the difference, the difference that offends the Nazi in all of us. It is deeply troubling, but we must face the fact that, for the Nazis, the killings of Jews were not murders but executions. By any civilized standards, the Shoah was the most egregious and abominable genocide, but Hitler, Himmler, Heydrich, Göring, Goebbels, and others convinced themselves that it was justified capital punishment on a mass scale. The Holocaust was the opposite of a frenzied and imponderable “witch hunt”; it was a methodical and intelligible pogrom of the prophetic. Witches, as commonly conceived, do not exist; a prophetic people, biblically understood, does.

Nazi anti-Semitism, like most anti-Semitism, is an effort to escape our humanity before God: in despising and/or executing the Jews, we are really rebelling against and/or murdering ourselves as spirit. As with so many things, going back to the Hebrew Bible helps us understand this. In the book of Esther, Haman, King Ahasuerus’s favorite, hates Mordecai, a Diaspora Jew, because he will “not bow down or do obeisance” to him (3:2). We are not told precisely why Mordecai will not bow, but it clearly is a matter of his Jewish identity and conscience (3:4).17 Haman is infuriated and encourages the Persian king to target the Jews more generally because they have “different laws” (3:8). As a people who serve God and keep their own counsels, the “alterity” of the Jews has long called up violent animosity that wants to dominate and even to eliminate them. The natural mind is erotic and does not relish being chastised and relativized by the demands of a supernatural faith. Indeed, one of the deep paradoxes of human history is that unconstrained erotic love often displays a dynamic similar to that of anti-Semitic and other forms of hatred. Consider the following two quotations:

“So,” she [Diotima] said, “the simple truth of the matter is that people love goodness. Yes?”

“Yes,” I [Socrates] answered.

“But hadn’t we better add that they want to get goodness for themselves?” she asked.

17 See Joyce G. Baldwin, Esther: An Introduction and Commentary (Leicester, England: InterVarsity Press, 1984), p. 28.